Published online Dec 21, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i47.112921

Revised: September 10, 2025

Accepted: November 3, 2025

Published online: December 21, 2025

Processing time: 132 Days and 10 Hours

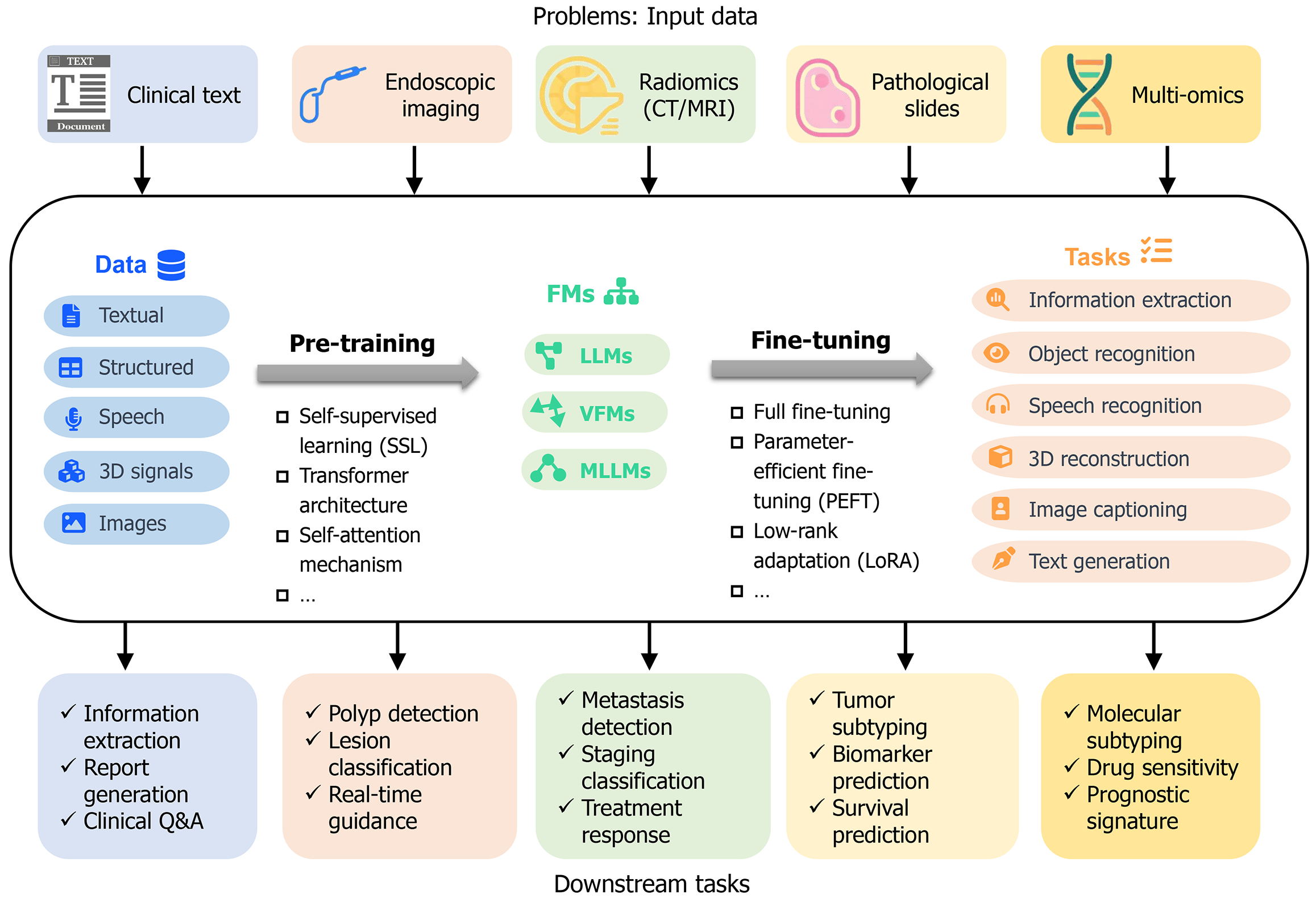

Gastrointestinal (GI) cancers represent a major global health concern due to their high incidence and mortality rates. Foundation models (FMs), also referred to as large models, represent a novel class of artificial intelligence technologies that have demonstrated considerable potential in addressing these challenges. These models encompass large language models (LLMs), vision FMs (VFMs), and multimodal LLMs (MLLMs), all of which utilize transformer architectures and self-supervised pre-training on extensive unlabeled datasets to achieve robust cross-domain generalization. This review delineates the principal applications of these models: LLMs facilitate the structuring of clinical narratives, extraction of insights from medical records, and enhancement of physician-patient commu

Core Tip: This review synthesizes applications of foundation models in gastrointestinal cancer, from clinical text structuring and image analysis to multimodal data integration. Despite current knowledge gaps and challenges like data standardization, it highlights foundation models’ transformative potential, urging refined models and collaborations to advance gastroin

- Citation: Shi L, Huang R, Zhao LL, Guo AJ. Foundation models: Insights and implications for gastrointestinal cancer. World J Gastroenterol 2025; 31(47): 112921

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v31/i47/112921.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i47.112921

Gastrointestinal (GI) cancers represent some of the most prevalent and lethal malignancies worldwide, imposing a substantial burden on public health[1]. Their multifactorial etiology and heterogeneous clinical manifestations make them difficult to study and treat using current methods[2]. Nevertheless, the advent of next-generation artificial intelligence (AI) models, known as oundation odels (FMs), offers novel avenues for addressing these challenges[3]. These models, trained on vast amounts of datasets, have the power to handle complex tasks, thereby presenting promising strategies to mitigate this worldwide health concern[4].

Unlike early AI methods that targeted isolated tasks or limited data modalities, FMs can integrate diverse medical data types, including endoscopic images, pathology slides, electronic health records (EHRs), genomic data, and clinical narratives[5]. This integrative capability is particularly pertinent to GI cancers, which often progress through a defined pattern (e.g., Correa’s cascade from gastritis to cancer)[6]. Accurate risk assessment, early diagnosis, and therapeutic decision-making require comprehensive data interpretation. However, current knowledge regarding the application of FMs in GI cancer remains limited, underscoring the imperative to systematically review current implementations and delineate prospective research trajectories to advance FM utilization in this domain.

Traditional computational biology techniques, such as support vector machines (SVMs) and random forests, alongside more recent deep-learning approaches like convolutional neural networks (CNNs), have made incremental advances in GI cancer research[7]. Nevertheless, these methods face major limitations, including dependence on labor-intensive, high-quality annotations; heterogeneity of datasets across institutions; and a predominant focus on unimodal data (e.g., imaging or genomics in isolation). These constraints highlight the necessity for cross-modal, large-scale pre-trained models[8].

Recent breakthroughs in general-purpose FMs, exemplified by ChatGPT, Stable Diffusion, and related architectures, have introduced a new paradigm shift in GI cancer research[5,9]. Their innovation resides in exceptional generalizability and cross-domain adaptability, facilitated by transformer-based architectures comprising billions of parameters pre-trained on vast, diverse datasets[10]. This pre-training engenders universal representations transferable to a broad spectrum of downstream tasks, maintaining robust performance even with limited or unlabeled data. Compared to traditional methods, FMs offer distinct advantages: Billion-scale parameterization combined with self-supervised learning (SSL) enables deep feature extraction and fusion of heterogeneous data; zero- or few-shot transfer learning substantially diminishes reliance on annotated datasets[11]. This review retrospectively synthesizes key FMs applied in GI cancer research, focusing on three principal categories: Large language models (LLMs) for clinical decision support leveraging EHRs; vision models [e.g., Vision Transformer (ViT) architectures] for endoscopic image analysis; and multimodal fusion models integrating imaging, omics, and pathology data. It is noteworthy that this research field is rapidly evolving, with some models already operational and others exploratory yet exhibiting considerable translational potential.

This section provides a concise historical overview of AI development to contextualize the emergence of FMs for researchers less familiar with the field. The conceptual foundation of AI traces back to Alan Turing’s 1950 proposal of the "Turing Test", envisioning computational simulation of human intelligence[12]. The 1956 Dartmouth Conference marked a seminal milestone, formally introducing the term "artificial intelligence" and transitioning the field from theoretical inquiry to systematic investigation[13]. AI evolution encompasses three major phases: The nascent period (1950s-1970s), dominated by symbolic logic and expert systems. For example, the Perceptron model developed by Frank Rosenblatt in 1957 attempted to realize classification learning through neural networks but hit a bottleneck due to hardware limitations[14]; the revival period (1980s-2000s) , characterized by statistical learning and big data exemplified by IBM's Deep Blue (which defeated the world chess champion in 1997) and Watson (which won the Jeopardy championship in 2011) veri

The concept of FMs was initially introduced by the Center for Research on Foundation Models (CRFM) at Stanford University in 2021[11]. CRFM characterizes FMs as models trained on extensive and diverse datasets, typically via large-scale SSL, that can be adapted to a variety of downstream tasks through fine-tuning. These models transcend the tra

A principal distinction between FMs and conventional AI models lies in their methodological approach. Traditional models, such as SVMs and CNNs, are typically designed for narrowly defined tasks and require substantial labeled datasets for each specific application[15]. Consequently, these models exhibit limited generalizability and are not readily adaptable to novel tasks; for example, a model trained to detect gastric cancer pathology cannot be directly repurposed for colorectal cancer (CRC) lymph node identification[23]. In contrast, FMs employ a two-stage process involving self-supervised pre-training followed by downstream fine-tuning[11]. During pre-training, FMs learn from vast quantities of unlabeled data, such as medical images and textual corpora, through tasks like masked reconstruction. Subsequently, fine-tuning enables adaptation to new tasks with relatively small labeled datasets. This paradigm allows a single pre-trained model to be deployed across multiple scenarios. Architectures such as GPT utilize the Transformer framework and autoregressive language modeling, training on extensive internet text corpora to internalize language patterns without manual annotation[16]. This SSL strategy endows FMs with adaptability across diverse tasks, including medical question answering and clinical case summarization, requiring only modest fine-tuning. The capacity for one-time training followed by multi-task reuse underpins FMs’ ability to generalize across domains and modalities, encompassing text, images, and speech, thereby advancing from task-specific models toward more generalized intelligence[5].

The foundational principles of FMs rest upon the integration of architectural design, algorithmic strategies, and technical paradigms, collectively facilitating their versatility and scalability[11]. Architecturally, FMs predominantly adopt the Transformer framework[16], wherein the self-attention mechanism dynamically assigns weights to different elements within a sequence, enabling context-sensitive processing. For example, the term “gastric” may activate distinct medical concepts depending on its contextual usage, such as in “gastric cancer” vs “gastric bezoar”. Algorithmically, FMs follow a pre-training and fine-tuning paradigm. Pre-training constructs a universal knowledge base from large-scale unlabeled data via SSL techniques; for instance, Masked Language Modeling tasks involve predicting obscured text segments (e.g., “Colorectal [MASK] screening guidelines”) to learn associations among medical concepts. Contrastive learning methods align multimodal features, such as correlating endoscopic images with corresponding pathological descriptions[11]. This data-driven approach diminishes dependence on annotated datasets and, when combined with extensive model parameters and massive training corpora, yields substantial performance gains. Fine-tuning adjusts model parameters on task-specific datasets, enabling rapid adaptation to downstream applications; for example, after fine-tuning on tumor classification, the model can accurately delineate cancerous regions in pathology images[11].

FMs can be classified into three categories based on input modalities: LLMs, Vision FMs (VFMs), and Multimodal LLMs (MLLMs)[10]. LLMs are sophisticated neural networks comprising billions of parameters, surpassing traditional language models in performance, with model size generally correlating with efficacy. For example, BioBERT, pre-trained on PubMed abstracts and clinical notes, has enhanced the accuracy of drug-drug interaction predictions[24]. GPT-3 employs in-context learning to generate text completions, overcoming prior limitations[17]. Applications of LLMs include structuring clinical narratives (e.g., extracting gastric cancer TNM staging from medical records), synthesizing evidence from literature (e.g., summarizing clinical trial outcomes for PD-1 inhibitors), and facilitating doctor-patient communi

To provide a contextual understanding of how FMs tackle challenges associated with GI cancers, Figure 1 presents their application framework. It delineates five primary data inputs, further details the processes of pre-training and subsequent fine-tuning methods, applied to various FMs including LLMs, VFMs, and MLLMs. The framework also highlights the spectrum of downstream tasks facilitated by these models, ranging from information extraction to mo

To offer a focused overview of FMs specifically designed for GI cancer research, we first present a summary of FMs with validated applications in GI cancer across language, vision, and multimodal domains in Table 1. This summary emphasizes most importantly, their distinct use cases within GI cancer research, categorized as NLP, endoscopy (Endo), radiology (Radio), and pathology (PA). A critical annotation in the "GI cancer applications" column, denoted as "Directly", signifies that the model was employed for GI cancer-related tasks (e.g., NLP, Endo, Radio, PA, or MLLM) without requiring further modification or fine-tuning, thereby underscoring its intrinsic adaptability to clinical demands.

| Name | Type | Creator | Year | Architecture | Parameters | Modality | OSS | GI cancer applications |

| BERT | LLM | 2018 | Encoder-only transformer | 110M (base), 340M (large) | Text | Yes | NLP, Radio, MLLM | |

| GPT-3 | LLM | OpenAI | 2020 | Decoder-only transformer | 175B | Text | No | NLP |

| ViT | Vision | 2020 | Encoder-only transformer | 86M (base), 307M (large), 632M (huge) | Image | Yes | Endo, Radio, PA, MLLM | |

| DINOv1 | Vision | Meta | 2021 | Encoder-only transformer | 22M, 86M | Image | Yes | Endo, PA |

| CLIP | MM | OpenAI | 2021 | Encoder-encoder | 120-580M | Text, Image | Yes | Endo, Radio, MLLM, directly1 |

| GLM-130B | LLM | Tsinghua | 2022 | Encoder-decoder | 130B | Text | Yes | NLP |

| Stable Diffusion | MM | Stability AI | 2022 | Diffusion model | 1.45B | Text, Image | Yes | NLP, Endo, MLLM, directly |

| BLIP | MM | Salesforce | 2022 | Encoder-decoder | 120M (base), 340M (large) | Text, Image | Yes | Radio, MLLM, directly |

| YouChat | LLM | You.com | 2022 | Fine-tuned LLMs | Unknown | Text | No | NLP |

| Bard | MM | 2023 | Based on PaLM 2 | 340B estimated | Text, Image, Audio, Code | No | NLP | |

| Bing Chat | MM | Microsoft | 2023 | Fine-tuned GPT-4 | Unknown | Text, Image | No | NLP |

| Mixtral 8x7B | LLM | Mistral AI | 2023 | Decoder-only, Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) | 46.7B total (12.9B active per token) | Text | NLP | |

| LLaVA | MM | Microsoft | 2023 | Vision encoder, LLM | 7B, 13B | Text, Image | Yes | PA, MLLM |

| DINOv2 | Vision | Meta | 2023 | Encoder-only transformer | 86M to 1.1B | Image | Yes | Endo, Radio, PA, MLLM, directly |

| Claude 2 | LLM | Anthropic | 2023 | Decoder-only transformer | Unknown | Text | No | NLP |

| GPT-4 | MM | OpenAI | 2023 | Decoder-only transformer | 1.8T (Estimated) | Text, Image | No | NLP, Endo, MLLM, directly |

| LLaMa 2 | LLM | Meta | 2023 | Decoder-only transformer | 7B, 13B, 34B, 70B | Text | Yes | NLP, Endo, MLLM, directly |

| SAM | Vision | Meta | 2023 | Encoder-decoder | 375M, 1.25G, 2.56G | Image | Yes | Endo, directly |

| GPT-4V | MM | OpenAI | 2023 | MM transformer | 1.8T | Text, Image | No | Endo, MLLM |

| Qwen | NLP | Alibaba | 2023 | Decoder-only transformer | 70B, 180B, 720B | Text | Yes | NLP, MLLM |

| GPT-4o | MM | OpenAI | 2024 | MM transformer | Unknown (Larger than GPT-4) | Text, Image, Video | No | NLP |

| LLaMa 3 | LLM | Meta | 2024 | Decoder-only transformer | 8B, 70B, 400B | Text | Yes | NLP, directly |

| Gemini 1.5 | MM | 2024 | MM transformer | 1.6T | Text, Image, Video, Audio | No | NLP, Radio, directly | |

| Claude 3.7 | MM | Anthropic | 2024 | Decoder-only transformer | Unknown | Text, Image | No | NLP, directly |

| YOLOWorld | Vision | IDEA | 2024 | CNN + RepVL-PAN vision-language fusion | 13-110M (depending on scale) | Text, Image | Yes | Endo, directly |

| DeepSeek | LLM | DeepSeek | 2025 | Decoder-only transformer | 671B | Text | Yes | NLP |

| Phi-4 | LLM | Microsoft | 2025 | Decoder-only transformer | 14B (plus), 7B (mini) | Text | Yes | Endo |

The evolution of GI-related FMs reveals a discernible trajectory of enhanced capabilities and improved alignment with clinical requirements. The introduction of Transformer-based architectures by models such as BERT in 2018 laid the foundational groundwork for contemporary FMs, facilitating subsequent advancements in their medical domain adaptation. Between 2020 and 2021, language-centric FMs, including GPT-3 and GLM-130B, experienced substantial scaling, encompassing tens to hundreds of billions of parameters. This expansion augmented their proficiency in managing unstructured GI cancer data, enabling tasks such as the extraction of phenotypic characteristics and treatment information from EHRs and scientific literature. Concurrently, vision-oriented FMs, exemplified by ViT and DINO, adapted Transformer architectures for image-based applications, addressing pivotal challenges in GI cancer diagnosis. Leveraging transfer learning, these models demonstrated high accuracy in detecting early gastric and colorectal lesions within pathology slides and endoscopic video data.

Post-2021 developments witnessed a shift towards multimodal FMs, which further enhanced clinical utility. Models such as CLIP, BLIP, and Stable Diffusion integrated textual and visual encoding capabilities, facilitating end-to-end workflows including lesion localization in radiological imaging and cross-validation of pathology reports with endo

The analysis of natural language, characterized by its inherent unstructured nature, has historically posed significant challenges for computational processing through rule-based or traditional algorithmic approaches, particularly within the domain of medical texts that contain specialized terminology and complex syntactic structures[26]. However, since the early 2020s, the rapid advancement of LLMs has transformed the field of NLP, establishing these models as the pre

LLMs possess the capability to generate novel, contextually relevant text rather than merely reproducing or summarizing existing information[17]. The widespread adoption and standardization of LLMs have significantly democratized NLP, enabling researchers without extensive technical expertise to employ models such as GPT and BERT for practical applications[10]. These models can store and retrieve extensive knowledge bases and extract structured information from medical documents, including radiology and pathology reports, and can even offer medical recom

Table 2 and Supplementary Table 1 provide a comprehensive overview of 69 representative studies on NLP and LLM applications in GI cancers conducted between 2011 and 2025. These studies encompass traditional NLP methodologies based on rule sets, lexicons, and statistical learning (Supplementary Table 1), alongside the rapidly emerging Tran

| Ref. | Year | Models | Objectives | Datasets | Performance | Evaluation |

| Syed et al[29] | 2022 | BERTi | Developed fine-tuned BERTi for integrated colonoscopy reports | 34165 reports | F1-scores of 91.76%, 92.25%, 88.55% for colonoscopy, pathology, and radiology | Manual chart review by 4 expert-guided reviewer |

| Lahat et al[30] | 2023 | GPT | Assessed GPT performance in addressing 110 real-world gastrointestinal inquiries | 110 real-life questions | Moderate accuracy (3.4-3.9/5) for treatment and diagnostic queries | Assessed by three gastroenterologists using a 1-5 scale for accuracy etc. |

| Lee et al[31] | 2023 | GPT-3.5 | Examined GPT-3.5’s responses to eight frequently asked colonoscopy questions | 8 colonoscopy-related questions | GPT answers had extremely low text similarity (0%-16%) | Four gastroenterologists rated the answers on a 7-point Likert scale |

| Emile et al[32] | 2023 | GPT-3.5 | Analyzed GPT-3.5’s ability to generate appropriate responses to CRC questions | 38 CRC questions | 86.8% deemed appropriately, with 95% concordance on 2022 ASCRS guidelines | Three surgery experts assessed answers using ASCRS guidelines |

| Moazzam et al[33] | 2023 | GPT | Investigated the quality of GPT’s responses to pancreatic cancer-related questions | 30 pancreatic cancer-questions | 80% responses were “very good” or “excellent” | Responses were graded by 20 experts against a clinical benchmark |

| Yeo et al[34] | 2023 | GPT | Assessed GPT’s performance in answering questions regarding cirrhosis and HCC | 164 questions about cirrhosis and HCC | 79.1% correctness for cirrhosis and 74% for HCC, but only 47.3% comprehensiveness | Responses were reviewed by two hepatologists and resolved by a 3rd reviewer |

| Cao et al[35] | 2023 | GPT-3.5 | Examined GPT-3.5’s capacity to answer on liver cancer screening and diagnosis | 20 questions | 48% answers were accurate, with frequent errors in LI-RADS categories | Six fellowship-trained physicians from three centers assessed answers |

| Gorelik et al[36] | 2024 | GPT-4 | Evaluated GPT-4’s ability to provide guideline-aligned recommendations | 275 colonoscopy reports | Aligned with experts in 87% of scenarios, showing no significant accuracy gap | Advice assessed by consensus review with multiple experts |

| Gorelik et al[37] | 2023 | GPT-4 | Analyzed GPT-4’s effectiveness in post-colonoscopy management guidance | 20 clinical scenarios | 90% followed guidelines, with 85% correctness and strong agreement (κ = 0.84) | Assessed by two senior gastroenterologists for guideline compliance |

| Zhou et al[38] | 2023 | GPT-3.5 and GPT-4 | Developed a gastric cancer consultation system and automated report generator | 23 medical knowledge questions | 91.3% appropriate gastric cancer advice (GPT-4), 73.9% for GPT-3.5 | The evaluation was conducted by reviewers with medical standards |

| Yang et al[39] | 2025 | RECOVER (LLM) | Designed a LLM-based remote patient monitoring system for postoperative care | 7 design sessions, 5 interviews | Six major design strategies for integrating clinical guidelines and information | Clinical staff reviewed and provided feedback on the design and functionality |

| Kerbage et al[40] | 2024 | GPT-4 | Evaluated GPT-4’s accuracy in responding to IBS, IBD, and CRC screening | 65 questions (45 patients, 20 doctors) | 84% of answers were accurate | Assessed independently by three senior gastroenterologists |

| Tariq et al[41] | 2024 | GPT-3.5, GPT-4, and Bard | Compared the efficacy of GPT-3.5, GPT 4, and Bard (July 2023 version) in answering 47 common colonoscopy patient queries | 47 queries | GPT 4 outperformed GPT-3.5 and Bard, with 91.4% fully accurate responses vs 6.4% and 14.9%, respectively | Responses were scored by two specialists on a 0-2 point scale and resolved by a 3rd reviewer |

| Maida et al[42] | 2025 | GPT-4 | Evaluated GPT-4’s suitability in addressing screening, diagnostic, therapeutic inquiries | 15 CRC screening inquiries | 4.8/6 for CRC screening accuracy, 2.1/3 for completeness scored | Assessment involved 20 experts and 20 non-experts rating the answers |

| Atarere et al[43] | 2024 | BingChat, GPT, YouChat | Tested the appropriateness of GPT, BingChat, and YouChat in patient education and patient-physician communication | 20 questions (15 on CRC screening and 5 patient-related) | GPT and YouChat provided more reliable answers than BingChat, but all models had occasional inaccuracies | Two board-certified physicians and one Gastroenterologist graded the responses |

| Chang et al[44] | 2024 | GPT-4 | Compared GPT-4’s accuracy, reliability, and alignment of colonoscopy recommendations | 505 colonoscopy reports | 85.7% of cases matched USMSTF guidelines | Assessment was conducted by an expert panel under USMSTF guidelines |

| Lim et al[45] | 2024 | GPT-4 | Compared a contextualized GPT model with standard GPT in colonoscopy screening | 62 example use cases | Contextualized GPT-4 outperformed standard GPT-4 | Compare the GPT4 against a model with relevant screening guidelines |

| Munir et al[46] | 2024 | GPT | Evaluated the quality and utility of responses for three GI surgeries | 24 research questions | Modest quality and vary significantly based on the type of procedure | Responses were graded by 45 expert surgeons |

| Truhn et al[47] | 2024 | GPT-4 | Created a structured data parsing module with GPT-4 for clinical text processing | 100 CRC reports | 99% accuracy for T-stage extraction, 96% for N-stage, and 94% for M-stage | Accuracy of GPT-4 was compared with manually extracted data by experts |

| Choo et al[48] | 2024 | GPT | Designed a clinical decision-support system to generate personalized management plans | 30 stage III recurrent CRC patients | 86.7% agree with tumor board decisions, 100% for second-line therapies | The recommendations were compared with the decision plans made by the MDT |

| Huo et al[49] | 2024 | GPT, BingChat, Bard, Claude 2 | Established a multi-AI platform framework to optimize CRC screening recommendations | Responses for 3 patient cases | GPT aligned with guidelines in 66.7% of cases, while other AIs showed greater divergence | Clinician and patient advice was compared to guidelines |

| Pereyra et al[50] | 2024 | GPT-3.5 | Optimized GPT-3.5 for personalized CRC screening recommendations | 238 physicians | GPT scored 4.57/10 for CRC screening, vs 7.72/10 for physicians | Answers were compared against a group of surgeons |

| Peng et al[51] | 2024 | GPT-3.5 | Built a GPT-3.5-powered system for answering CRC-related queries | 131 CRC questions | 63.01 mean accuracy, but low comprehensiveness scores (0.73-0.83) | Two physicians reviewed each response, with a third consulted for discrepancies |

| Ma et al[52] | 2024 | GPT-3.5 | Established GPT-3.5-based quality control for post-esophageal ESD procedures | 165 esophageal ESD cases | 92.5%-100% accuracy across post-esophageal ESD quality metrics | Two QC members and a senior supervisor conducted assessment |

| Cohen et al[53] | 2025 | LLaMA-2, Mistral-v0.1 | Explored the ability of LLMs to extract PD-L1 biomarker details for research purposes | 232 EHRs from 10 cancer types | Fine-tuned LLMs outperformed LSTM trained on > 10000 examples | Assessed by 3 clinical experts against manually curated answers |

| Scherbakov et al[54] | 2025 | Mixtral 8 × 7 B | Assessed LLM to extract stressful events from social history of clinical notes | 109556 patients, 375334 notes | Arrest or incarceration (OR = 0.26, 95%CI: 0.06-0.77) | One human reviewer assessed the precision and recall of extracted events |

| Chatziisaak et al[55] | 2025 | GPT-4 | Evaluated the concordance of therapeutic recommendations generated by GPT | 100 consecutive CRC patients | 72.5% complete concordance, 10.2% partial concordance, and 17.3% discordance | Three reviewers independently assessed concordance with MDT |

| Saraiva et al[56] | 2025 | GPT-4 | Assessed GPT-4’s performance in interpreting images in gastroenterology | 740 images | Capsule endoscopy: Accuracies 50.0%-90.0% (AUCs 0.50-0.90) | Three experts reviewed and labeled images for CE |

| Siu et al[57] | 2025 | GPT-4 | Evaluated the efficacy, quality, and readability of GPT-4’s responses | 8 patient-style questions | Accurate (40), safe (4.25), appropriate (4.00), actionable (4.00), effective (4.00) | Evaluated by 8 colorectal surgeons |

| Horesh et al[58] | 2025 | GPT-3.5 | Evaluated management recommendations of GPT in clinical settings | 15 colorectal or anal cancer patients | Rating 48 for GPT recommendations, 4.11 for decision justification | Evaluated by 3 experienced colorectal surgeons |

| Ellison et al[59] | 2025 | GPT-3.5, Perplexity | Compared readability using different prompts | 52 colorectal surgery materials | Average 7.0-9.8, Ease 53.1-65.0, Modified 9.6-11.5 | Compared mean scores between baseline and documents generated by AI |

| Ramchandani et al[60] | 2025 | GPT-4 | Validated the use of GPT-4 for identifying articles discussing perioperative and preoperative risk factors for esophagectomy | 1967 studies for title and abstract screening | Perioperative: Agreement rate = 85.58%, AUC = 0.87. Preoperative: Agreement rate = 78.75%, AUC = 0.75 | Decisions were compared with those of three independent human reviewers |

| Zhang et al[61] | 2025 | GPT-4, DeepSeek, GLM-4, Qwen, LLaMa3 | To evaluate the consistency of LLMs in generating diagnostic records for hepatobiliary cases using the HepatoAudit dataset | 684 medical records covering 20 hepatobiliary diseases | Precision: GPT-4 reached a maximum of 93.42%. Recall: Generally below 70%, with some diseases below 40% | Professional physicians manually verified and corrected all the data |

| Spitzl et al[62] | 2025 | Claude-3.5, GPT-4o, DeepSeekV3, Gemini 2 | Assessed the capability of state-of-the-art LLMs to classify liver lesions based solely on textual descriptions from MRI reports | 88 fictitious MRI reports designed to resemble real clinical documentation | Micro F1-score and macro F1-score: Claude 3.5 Sonnet 0.91 and 0.78, GPT-4o 0.76 and 0.63, DeepSeekV3 0.84 and 0.70, Gemini 2.0 Flash 0.69 and 0.55 | Model performance was assessed using micro and macro F1-scores benchmarked against ground truth labels |

| Sheng et al[63] | 2025 | GPT-4o and Gemini | Investigated the diagnostic accuracies for focal liver lesions | 228 adult patients with CT/MRI reports | Two-step GPT-4o, single-step GPT-4o and single-step Gemini (78.9%, 68.0%, 73.2%) | Six radiologists reviewed the images and clinical information in two rounds (alone, with LLM) |

| Williams et al[64] | 2025 | GPT-4-32K | Determined LLM extract reasons for a lack of follow-up colonoscopy | 846 patients' clinical notes | Overall accuracy: 89.3%, reasons: Refused/not interested (35.2%) | A physician reviewer checked 10% of LLM-generated labels |

| Lu et al[65] | 2025 | MoE-HRS | Used a novel MoE combined with LLMs for risk prediction and personalized healthcare recommendations | SNPs, medical and lifestyle data from United Kingdom Biobank | MoE-HRS outperformed state-of-the-art cancer risk prediction models in terms of ROC-AUC, precision, recall, and F1 score | LLMs-generated advice were validated by clinical medical staff |

| Yang et al[66] | 2025 | GPT-4 | Explored the use of LLMs to enhance doctor-patient communication | 698 pathology reports of tumors | Average communication time decreased by over 70%, from 35 to 10 min (P < 0.001) | Pathologists evaluated the consistency between original and AI reports |

| Jain et al[67] | 2025 | GPT-4, GPT-3.5, Gemini | Studied the performance of LLMs across 20 clinicopathologic scenarios in gastrointestinal pathology | 20 clinicopathologic scenarios in GI | Diagnostic accuracy: Gemini Advanced (95%, P = 0.01), GPT-4 (90%, P = 0.05), GPT-3.5 (65%) | Two fellowship-trained pathologists independently assessed the responses of the models |

| Xu et al[68] | 2025 | GPT-4, GPT-4o, Gemini | Assessed the performance of LLMs in predicting immunotherapy response in unresectable HCC | Multimodal data from 186 patients | Accuracy and sensitivity: GPT-4o (65% and 47%) Gemini-GPT (68% and 58%). Physicians (72% and 70%) | Six physicians (three radiologists and three oncologists) independently assessed the same dataset |

| Deroy et al[69] | 2025 | GPT-3.5 Turbo | Explored the potential of LLMs as a question-answering (QA) tool | 30 training and 50 testing queries | A1: 0.546 (maximum value); A2: 0.881 (maximum value across three runs) | Model-generated answers were compared to the gold standard |

| Ye et al[70] | 2025 | BioBERT-based | Proposed a novel framework that incorporates clinical features to enhance multi-omics clustering for cancer subtyping | Six cancer datasets across three omics levels | Mean survival score of 2.20, significantly higher than other methods | Three independent clinical experts review and validate the clustering results |

The volume and temporal distribution of studies reveal distinct trends between traditional NLP and modern LLM research. Over a 14-year span (2011-2025), only 25 studies focused on traditional NLP approaches, whereas LLM-related publications surged from zero to 42 within five years following 2020, indicating rapid expansion. Since 2023, more than ten new investigations annually have employed frameworks such as LLaMA-2 and Gemini, establishing LLMs as the most dynamic area in intelligent text processing for GI cancers.

As detailed in Table 2[29-70], LLMs have been extensively applied to address a variety of GI cancer-related challenges. For example, GPT series models have been utilized to respond to diverse clinical inquiries, including colon cancer screening, pancreatic cancer treatment, and the diagnosis of cirrhosis and liver cancer. These applications underscore the robust language comprehension and generation capabilities of LLMs, enabling them to manage medical knowledge across multiple domains and provide preliminary informational support for clinicians and patients. For example, in 2023, Emile et al[32] found that GPT-3.5 could generate appropriate responses for 86.8% of 38 CRC questions, with 95% concordance with the 2022 ASCRS guidelines.

Several studies have focused on leveraging LLMs to develop personalized medical systems. Choo et al[48] designed a clinical decision support system that used GPT to generate personalized management plans for stage III recurrent CRC patients. The plans showed 86.7% agreement with the decisions of the tumor board, and 100% agreement for second-line therapies. This indicates that LLMs have the potential to provide customized medical solutions based on patients' specific conditions. LLMs have also been applied to automated report generation and data processing. In 2023, Zhou et al[38] developed a gastric cancer consultation system and an automated report generator based on GPT-3.5 and GPT-4. GPT-4 provided appropriate gastric cancer advice in 91.3% of cases. Moreover, in 2024, Truhn et al[47] used GPT-4 to create a structured data parsing module for clinical text processing, achieving 99%, 96%, and 94% accuracy in extracting T-stage, N-stage, and M-stage respectively, which greatly improved the efficiency of data processing. To further facilitate the application of LLMs, some researchers have dedicated to model comparison and optimization. In 2024, Tariq et al[41] compared the performance of GPT-3.5, GPT-4, and Bard in answering 47 common colonoscopy patient queries. They found that GPT-4 outperformed the others, with 91.4% fully accurate responses. This helps researchers understand the performance of different models and select more suitable ones for optimization and application.

Despite these advancements, several challenges hinder the clinical translation of LLMs in GI cancer. First, while LLMs often exhibit remarkable accuracy and promising applications, these models are not specifically designed for medical contexts. Several studies have further revealed inconsistencies or uncertainties in their reported outcomes. Pereyra et al[50] found GPT-3.5 scored just 4.57/10 for CRC screening recommendations, far below physicians’ 7.72/10, while Tariq et al[41] revealed stark model disparities: GPT-4 delivered 91.4% fully accurate colonoscopy query responses, but GPT-3.5 and Bard only achieved 6.4% and 14.9%, respectively. Even for common tasks, Cao et al[35] noted GPT-3.5 had only 48% accuracy in liver cancer screening (with frequent category errors), demonstrating that generalization issues extend beyond rare cases.

Second, data privacy and compliance risks persist. For example, most widely adopted LLMs (e.g., Claude-3.5) are trained on heterogeneous non-medical datasets, lacking inherent safeguards for sensitive GI cancer data. This creates significant HIPAA/GDPR compliance concerns, raising questions about how patient data is protected during model deployment.

Third, interpretability gaps undermine clinical trust, while GPT-4 shows strong guideline alignment (87% agreement with experts in Gorelik et al[36]), its black-box nature means clinicians cannot trace the reasoning behind outputs, a critical flaw in high-stakes scenarios. This is exemplified by Yeo et al[34], where GPT achieved 74% correctness for HCC-related queries but only 47.3% comprehensiveness. Clinicians could not verify why incomplete information was generated, limiting reliance on such tools.

Together, these challenges, inconsistent performance, privacy risks, and opaque reasoning, create barriers to integrating LLMs into routine GI cancer care, as they fail to meet the rigor and reliability required for clinical decision-making. To address the aforementioned challenges and accelerate the clinical integration of LLMs, future research should prioritize directions based on findings presented in Table 2. Such as enhancing fine-tuning LLMs on GI-specific datasets, integrating rule-based checks to verify outputs (with traditional NLP in Supplementary Table 1), using open-source models with local deployment for privacy-sensitive data handling.

Since the early 2020s, VFMs have revolutionized biomedical image analysis[25,71]. These models acquire universal visual representations from extensive collections of unlabeled medical images and can be adapted to specialized tasks, such as GI cancer detection, through fine-tuning on relatively small labeled datasets[72]. For example, in CRC screening, FMs have demonstrated substantial improvements in polyp detection accuracy following fine-tuning. Moreover, VFMs are increasingly employed in cross-modal applications[73]. They integrate different modalities of data to achieve a more comprehensive understanding of disease pathology. This integration necessitates the processing of diverse datasets and significant computational resources. However, the emergence of open-source VFMs, including MedSAM and Bio

VFMs in endoscopy: Endoscopy constitutes a critical modality for the diagnosis and management of GI cancers, generating vast quantities of images that capture essential information ranging from early lesions to advanced tumor stages. Traditionally, the interpretation of these images has relied heavily on the expertise of experienced endoscopists, a process that is both time-intensive and susceptible to human error, especially given the increasing volume of examinations[75]. VFMs offer a novel solution by enabling direct analysis of endoscopic video streams, facilitating the automatic localization and classification of lesions such as polyps and ulcers.

Table 3 summarizes 19 recent studies (2023-2025), all of which intentionally adapt VFMs for endoscopy applications. Due to space constraints, more detailed information about these models, such as Country, Dataset sizes, Evaluation metrics, Fine-tuning strategies, Performance benchmarks, and GPUs, is presented in Supplementary Table 2. In contrast, Supplementary Table 3 focuses on VFMs benchmarked in endoscopy. It includes models that are not specifically trained or fine-tuned for endoscopy, but some models in Table 3[76-94] use these for benchmarking. This table holds significance as it provides reference results from general or medical-general VFMs. It highlights the transferability of VFMs’ visual feature extraction capabilities and enriches the overall analysis of VFMs in the context of endoscopy.

| Model | Year | Architecture | Training algorithm | Parameters | Datasets | Disease studied | Model type | Source code link |

| Surgical-DINO[76] | 2023 | DINOv2 | LoRA layers added to DINOv2, optimizing the LoRA layers | 86.72M | SCARED, Hamlyn | Endoscopic Surgery | Vision | https://github.com/BeileiCui/SurgicalDINO |

| ProMISe[77] | 2023 | SAM (ViT-B) | APM and IPS modules are trained while keeping SAM frozen | 1.3-45.6M | EndoScene, ColonDB etc. | Polyps, Skin Cancer | Vision | NA |

| Polyp-SAM[78] | 2023 | SAM | Strategy as pretrain only the mask decoder while freezing all encoders | NA | CVC-ColonDB Kvasir etc. | Colon Polyps | Vision | https://github.com/ricklisz/Polyp-SAM |

| Endo-FM[79] | 2023 | ViT B/16 | Pretrained using a self-supervised teacher-student framework, and fine-tuned on downstream tasks | 121M | Colonoscopic, LDPolyp etc. | Polyps, erosion, etc. | Vision | https://github.com/med-air/Endo-FM |

| ColonGPT[80] | 2024 | SigLIP-SO, Phi1.5 | Pre-alignment with image-caption pairs, followed by supervised fine-tuning using LoRA | 0.4-1.3B | ColonINST (30k+ images) | Colorectal polyps | Vision | https://github.com/ColonGPT/ColonGPT |

| DeepCPD[81] | 2024 | ViT | Hyperparameters are optimized for colonoscopy datasets, including Adam optimizer | NA | PolypsSet, CP-CHILD-A etc. | CRC | Vision | https://github.com/Zhang-CV/DeepCPD |

| OneSLAM[82] | 2024 | Transformer (CoTracker) | Zero-shot adaptation using TAP + Local Bundle Adjustment | NA | SAGE-SLAM, C3VD etc. | Laparoscopy, Colon | Vision | https://github.com/arcadelab/OneSLAM |

| EIVS[83] | 2024 | Vision Mamba, CLIP | Unsupervised Cycle‑Consistency | 63.41M | 613 WLE, 637 images | Gastrointestinal | Vision | NA |

| APT[84] | 2024 | SAM | Parameter-efficient fine-tuning | NA | Kvasir-SEG, EndoTect etc. | CRC | Vision | NA |

| FCSAM[85] | 2024 | SAM | LayerNorm LoRA fine-tuning strategy | 1.2M | Gastric cancer (630 pairs) etc. | GC, Colon Polyps | Vision | NA |

| DuaPSNet[86] | 2024 | PVTv2-B3 | Transfer learning with pre-trained PVTv2-B3 on ImageNet | NA | LaribPolypDB, ColonDB etc. | CRC | Vision | https://github.com/Zachary-Hwang/Dua-PSNet |

| EndoDINO[87] | 2025 | ViT (B, L, g) | DINOv2 methodology, hyperparameters tuning | 86M to 1B | HyperKvasir, LIMUC | GI Endoscopy | Vision | https://github.com/ZHANGBowen0208/EndoDINO/ |

| PolypSegTrack[88] | 2025 | DINOv2 | One-step fine-tuning on colonoscopic videos without first pre-training | NA | ETIS, CVC-ColonDB etc. | Colon polyps | Vision | NA |

| AiLES[89] | 2025 | RF-Net | Not fine-tuned from external model | NA | 100 GC patients | Gastric cancer | Vision | https://github.com/CalvinSMU/AiLES |

| PPSAM[90] | 2025 | SAM | Fine-tuning with variable bounding box prompt perturbations | NA | EndoScene, ColonDB etc. | Investigated in Ref. | Vision | https://github.com/SLDGroup/PP-SAM |

| SPHINX-Co[91] | 2024 | LLaMA-2 + SPHINX-X | Fine-tuned SPHINX-X on CoPESD with cosine learning rate scheduler | 7B, 13B | CoPESD | Gastric cancer | Multimodal | https://github.com/gkw0010/CoPESD |

| LLaVA-Co[91] | 2024 | LLaVA-1.5 (CLIP-ViT-L) | Fine-tuned LLaVA-1.5 on CoPESD with cosine learning rate scheduler | 7B, 13B | CoPESD | Gastric cancer | Multimodal | https://github.com/gkw0010/CoPESD |

| ColonCLIP[92] | 2025 | CLIP | Prompt tuning with frozen CLIP, then encoder fine-tuning with frozen prompts | 57M, 86M | OpenColonDB | CRC | Multimodal | https://github.com/Zoe-TAN/ColonCLIP-OpenColonDB |

| PSDM[93] | 2025 | Stable Diffusion + CLIP | Continual learning with prompt replay to incrementally train on multiple datasets | NA | PolypGen, ColonDB, Polyplus etc. | CRC | Vision, Generative | The original paper reported a GitHub link for this model, but it is currently unavailable |

| PathoPolypDiff[94] | 2025 | Stable Diffusion v1-4 | Fine-tuned Stable Diffusion v1-4 and locked first U-Net block, fine-tuned remaining blocks | NA | ISIT-UMR Colonoscopy Dataset | CRC | Generative | https://github.com/Vanshali/PathoPolyp-Diff |

VFMs demonstrate notable strengths in GI cancer endoscopy through multiple advanced approaches. Parameter-efficient variants such as Surgical-DINO (LoRA, 0.3% trainable) and APT/FCSAM (adapter-based, < 1%) achieve competitive results, while fully-fine-tuned Endo-FM reaches 73.9 Dice on CVC-12k[76,79]. With respect to multimodal reasoning, LLaVA-Co achieves GPT scores of 85.6/100 and mIoU 60.2% on ESD benchmarks[91]. Regarding unified architectures across tasks, SAM-derived pipelines (e.g., ProMISe[77], Polyp-SAM[78], APT[84], FCSAM[85], PP-SAM[90]) have so far been individually evaluated for either segmentation or detection metrics. This suggests a single foundation backbone could replace the current patchwork of bespoke CNNs. For generative augmentation, PSDM[93] and Patho

Supplementary Table 3 has unique value in the context of VFMs for GI endoscopy: It includes models that are not optimized specifically for endoscopy but still prove useful in benchmarking. For example, models like TimeSformer and ST-Adapter, despite lacking endoscopy-specific refinement, demonstrate certain value when used in the benchmarking of Endo-FM[79]. Meanwhile, general-purpose models such as SAM, Gemini-1.5, and Stable Diffusion are also tested in the benchmarking of other models like PPSAM[90], ColonCLIP[92] and PathoPolyp-Diff[94] respectively, showing their potential to support performance evaluation in this specialized field. These results confirm the general-purpose vision-language capabilities of models like CLIP and Gemini-1.5 (Supplementary Table 3), even when the base model has never been exposed to endoscope data.

Collectively, these findings show that VFMs, whether applied directly or through secondary development, play a pivotal role in GI cancer endoscopy tasks including polyp recognition and early lesion monitoring. They contribute to enhanced diagnostic efficiency and accuracy. Furthermore, the reviewed studies highlight the complementary strengths of diverse models in specific tasks, thereby laying the groundwork for future multi-model fusion systems aimed at intelligent endoscopic diagnosis.

VFMs in radiology: VFMs have become increasingly significant in radiology, particularly for GI cancer diagnosis, complementing traditional endoscopic approaches. Radiological modalities such as CT, MRI, and positron emission tomography play essential roles in initial cancer staging, metastasis detection, treatment monitoring, and postoperative recurrence identification[95]. Traditional radiology methods involve manually marking regions of interest and extracting features, which is reliable but time-consuming and constrained by limited data[96]. In contrast, VFMs using Transformer-based architectures enable automated processing of entire images, capturing intricate details of tumors and adjacent tissues. This reduces the need for manual annotation. The recent availability of large-scale, open-source VFMs pre-trained on millions of radiographs has facilitated fine-tuning on relatively small datasets, such as several dozen enhanced CT scans for gastric or CRC, using modest computing resources[97].

To summarize the application and development of VFMs in radiology for GI cancer, three key tables are presented in this section. Table 4 encapsulates 10 representative VFM studies, covering essential information such as model architecture, training algorithm, applied datasets. Supplementary Table 4 extends the content of Table 4 by providing more methodological details for the same 10 models, including specific sizes of datasets, evaluation metrics, fine-tuning strategies, performance benchmarks. Meanwhile, Supplementary Table 5 offers a set of models that were not specifically trained or fine-tuned for radiology tasks but were adopted as benchmarks by several models in Table 4[97-105], thereby providing a comparative context to assess the relative performance of VFMs tailored for radiology.

| Model | Year | Architecture | Training algorithm | Parameters | Datasets | Disease studied | Model type | Source code link |

| PubMedCLIP[98] | 2021 | CLIP | Fine-tuned on ROCO dataset for 50 epochs with Adam optimizer | NA | ROCO, VQA-RAD, SLAKE | Abdomen samples | Multimodal | https://github.com/sarahESL/PubMedCLIP |

| RadFM[97] | 2023 | MedLLaMA-13B | Pre-trained on MedMD and fine-tuned on RadMD | 14B | MedMD, RadMD etc. | Over 5000 diseases | Multimodal | https://github.com/chaoyi-wu/RadFM |

| Merlin[99] | 2024 | I3D-ResNet152 | Multi-task learning with EHR and radiology reports and fine-tuning for specific tasks | NA | 6M images, 6M codes and reports | Multiple diseases, Abdominal | Multimodal | NA |

| MedGemini[100] | 2024 | Gemini | Fine-tuning Gemini 1.0/1.5 on medical QA, multimodal and long-context corpora | 1.5B | MedQA, NEJM, GeneTuring | Various | Multimodal | https://github.com/Google-Health/med-gemini-medqa-relabelling |

| HAIDEF[101] | 2024 | VideoCoCa | Fine-tuning on downstream tasks with limited labeled data | NA | CT volumes and reports | Various | Vision | https://huggingface.co/collections/google/ |

| CTFM[102] | 2024 | Vision Model1 | Trained using a self-supervised learning strategy, employing a SegResNet encoder for the pre-training phase | NA | 26298 CT scans | CT scans (stomach, colon) | Vision | https://aim.hms.harvard.edu/ct-fm |

| MedVersa[103] | 2024 | Vision Model1 | Trained from scratch on the MedInterp dataset and adapted to various medical imaging tasks | NA | MedInterp | Various | Vision | https://github.com/3clyp50/MedVersa_Internal |

| iMD4GC[104] | 2024 | Transformer-based2 | A novel multimodal fusion architecture with cross-modal interaction and knowledge distillation | NA | GastricRes/Sur, TCGA etc. | Gastric cancer | Multimodal | https://github.com/FT-ZHOU-ZZZ/iMD4GC/ |

| Yasaka et al[105] | 2025 | BLIP-2 | LORA with specific fine-tuning of the fc1 layer in the vision and q-former models | NA | 5777 CT scans | Esophageal cancer via chest CT | Multimodal | NA |

First, in terms of architectural diversity and technical adaptation, VFMs have evolved from single-modal vision models to integrated multimodal systems. On one hand, vision-specific models focus on optimizing image feature extraction for GI-related scans. for example, CT-FM adopts a SegResNet encoder and uses SSL to process 26298 CT scans, targeting stomach and colon cancer imaging[102]; MedVersa, trained from scratch on the MedInterp dataset, is adapted to multiple medical imaging tasks, including GI cancer detection[103]. On the other hand, multimodal models integrate non-imaging data to enhance diagnostic accuracy. Merlin uses an I3D-ResNet152 architecture and incorporates multi-task learning with EHR and radiology reports, enabling it to handle abdominal GI diseases alongside other conditions[99]. Second, regarding disease coverage and clinical targeting, VFMs now address a broader spectrum of GI cancers while main

Unlike these specialized radiology models, several general-purpose VFMs, untailored for radiology, serve as bench

Despite the progress of VFMs in GI cancer radiology, several radiology-specific limitations and challenges remain evident in current research. For example, dataset bias and scarcity hinder model generalizability. Models like Yasaka et al[105] rely on relatively small, single-center datasets of 5777 CT scans, which may fail to capture the variability of GI cancer imaging across different populations or clinical settings. There is also limited focus on 3D radiological data. Most models (e.g., PubMedCLIP, RadFM) primarily process 2D images, while 3D CT/MRI volumes, critical for assessing tumor depth and spread in GI cancer, are less addressed (Merlin mentions 3D semantic segmentation with a Dice score of 0.798). To address these issues, future research should prioritize radiology-tailored recommendations. For instance, expand multi-center, diverse datasets for training so that future models could integrate data from global GI cancer centers to reduce bias. In practice, it is possible to combine TCGA data (used by iMD4GC) with real-world clinical scans to cover more ethnicities and disease stages[104]. Moreover, it is useful to enhance 3D data processing capabilities. Leveraging Merlin’s progress in 3D segmentation, future VFMs should optimize architectures for 3D GI cancer imaging to improve tumor staging accuracy, a key radiological task for treatment planning[99].

VFMs in pathology: Histopathology plays a pivotal role in cancer diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment. Traditionally, pathologists examined tissue slides under microscopes, a process that was slow, labor-intensive, and prone to errors stemming from variability in expertise. Such limitations occasionally resulted in misdiagnoses, particularly in complex cases[106]. The integration of digital technologies revolutionized this domain through whole-slide imaging (WSI), which converts glass slides into high-resolution digital images that retain all microscopic details[107]. But manual analysis of these extensive datasets was impractical. This led to the rise of computational pathology, which uses computer al

To elaborate on the application and advancement of VFMs in GI pathology, Table 5 encapsulates 28 representative VFM studies, showing the deployment of VFMs for tasks like detection & classification, segmentation, and histopathological assessment in GI WSIs. Due to space constraints, Supplementary Table 6 provides comprehensive methodological details for each corresponding model. These applications have markedly enhanced diagnostic efficiency and accuracy. Unlike the direct utilization of FMs in LLMs or endoscopic imaging, GI histopathology adopts a distinct technical approach, likely influenced by the extensive research in computational pathology favoring customized and specialized model architectures. By training and fine-tuning models on domain-specific pathological data, these VFMs achieve precise recognition and analysis of tumor features, rather than relying on general-purpose models.

| Model | Year | Architecture | Training Algorithm | Paras | WSIs | Tissues | Open source link |

| LUNIT-SSL[110] | 2021 | ViT-S | DINO; full fine-tuning and linear evaluation on downstream tasks | 22M | 3.7K | 32 | https://Lunitio.github.io/research/publications/pathology_ssl |

| CTransPath[111] | 2022 | Swin Transformer | MoCoV3 (SRCL); frozen backbone with linear classifier fine-tuning | 28M | 32K | 32 | https://github.com/Xiyue-Wang/TransPath |

| Phikon[112] | 2023 | ViT-B | iBOT (Masked Image Modeling); fine-tuned with ABMIL/TransMIL on frozen features | 86M | 6K | 16 | https://github.com/owkin/HistoSSLscaling |

| REMEDIS[113] | 2023 | BiT-L (ResNet-152) | SimCLR (contrastive learning); end-to-end fine-tuning on labeled ID/OOD data | 232M | 29K | 32 | https://github.com/google-research/simclr |

| Virchow[114] | 2024 | ViT-H, DINOv2 | DINOv2 (SSL); used frozen embeddings with simple aggregators | 632M | 1.5M | 17 | https://huggingface.co/paige-ai/Virchow |

| Virchow2[115] | 2024 | ViT-H | DINOv2 (SSL); fine-tuned with linear probes or full-tuning on downstream tasks | 632M | 3.1M | 25 | https://huggingface.co/paige-ai/Virchow2 |

| Virchow2G[115] | 2024 | ViT-G | DINOv2 (SSL); fine-tuned with linear probes or full fine-tuning | 1.9B | 3.1M | 25 | https://huggingface.co/paige-ai/Virchow2 |

| Virchow2G mini[115]1 | 2024 | ViT-S, Virchow2G | DINOv2 (SSL); distilled from Virchow2G, then fine-tuned on downstream tasks | 22M | 3.2M | 25 | https://huggingface.co/paige-ai/Virchow2 |

| UNI[9] | 2024 | ViT-L | DINOv2 (SSL); used frozen features with linear probes or few-shot learning | 307M | 100K | 20 | https://github.com/mahmoodlab/UNI |

| Phikon-v2[116] | 2024 | ViT-L | DINOv2 (SSL); frozen ViT and ABMIL ensemble fine-tuning | 307M | 58K | 30 | https://huggingface.co/owkin/phikon-v2 |

| RudolfV[117] | 2024 | ViT-L | DINOv2 (SSL); fine-tuned with optimizing linear classification layer and adapting encoder weights | 304M | 103K | 58 | https://github.com/rudolfv |

| HIBOU-B[118] | 2024 | ViT-B | DINOv2 (SSL); frozen feature extractor, trained linear classifier or attention pooling | 86M | 1.1M | 12 | https://github.com/HistAI/hibou |

| HIBOU-L[118]2 | 2024 | ViT-L | DINOv2 (SSL); frozen feature extractor, trained linear classifier or attention pooling | 307M | 1.1M | 12 | https://github.com/HistAI/hibou |

| H-Optimus-03 | 2024 | ViT-G | DINOv2 (SSL); linear probe and ABMIL on frozen features | 1.1B | > 500K | 32 | https://github.com/bioptimus/releases/ |

| Madeleine[119] | 2024 | CONCH | MAD-MIL; linear probing, prototyping, and full fine-tuning for downstream tasks | 86M | 23K | 2 | https://github.com/mahmoodlab/MADELEINE |

| COBRA[120] | 2024 | Mamba-2 | Self-supervised contrastive pretraining with multiple FMs and Mamba2 architecture | 15M | 3K | 6 | https://github.com/KatherLab/COBRA |

| PLUTO[121] | 2024 | FlexiVit-S | DINOv2; frozen backbone with task-specific heads for fine-tuning | 22M | 158K | 28 | NA |

| HIPT[122] | 2025 | ViT-HIPT | DINO (SSL); fine-tune with gradient accumulation | 10M | 11K | 33 | https://github.com/mahmoodlab/HIPT |

| PathoDuet[123] | 2025 | ViT-B | MoCoV3; fine-tuned using standard supervised learning on labeled downstream task data | 86M | 11K | 32 | https://github.com/openmedlab/PathoDuet |

| Kaiko[124] | 2025 | ViT-L | DINOv2 (SSL); linear probing with frozen encoder on downstream tasks | 303M | 29K | 32 | https://github.com/kaiko-ai/towards_large_pathology_fms |

| PathOrchestra[125] | 2025 | ViT-L | DINOv2; ABMIL, linear probing, weakly supervised classification | 304M | 300K | 20 | https://github.com/yanfang-research/PathOrchestra |

| THREADS[126] | 2025 | ViT-L, CONCHv1.5 | Fine-tune gene encoder, initialize patch encoder randomly | 16M | 47K | 39 | https://github.com/mahmoodlab/trident |

| H0-mini[127] | 2025 | ViT | Using knowledge distillation from H-Optimus-0 | 86M | 6K | 16 | https://huggingface.co/bioptimus/H0-mini |

| TissueConcepts[128] | 2025 | Swin Transformer | Frozen encoder with linear probe for downstream tasks | 27.5M | 7K | 14 | https://github.com/FraunhoferMEVIS/MedicalMultitaskModeling |

| OmniScreen[129] | 2025 | Virchow2 | Attention-aggregated Virchow2 embeddings fine-tuning | 632M | 48K | 27 | https://github.com/OmniScreen |

| BROW[130] | 2025 | ViT-B | DINO (SSL); self-distillation with multi-scale and augmented views | 86M | 11K | 6 | NA |

| BEPH[131] | 2025 | BEiTv2 | BEiTv2 (SSL); supervised fine-tuning on clinical tasks with labeled data | 86M | 11K | 32 | https://github.com/Zhcyoung/BEPH |

| Atlas[132] | 2025 | ViT-H, RudolfV | DINOv2; linear probing with frozen backbone on downstream tasks | 632M | 1.2M | 70 | NA |

The current research of VFMs in GI pathology presents distinct characteristics across three dimensions, with evidence supported by models from Table 5 and Supplementary Table 6. First, in terms of model architecture, there has been a clear trend toward diversification and scale expansion, with ViT variants becoming the dominant framework while complementary architectures continue to emerge. As shown in Table 5[9,110-132], early models (e.g., LUNIT-SSL) ado

Despite their promising progress, VFMs still face distinct limitations and challenges when applied to GI pathology, most of which are closely tied to the unique characteristics of pathological analysis and clinical workflows. First, over-reliance on large-scale, high-quality pathological datasets restricts accessibility. For example, models like Virchow2[115] and Atlas[132] use 3.1M and 1.2M WSIs respectively (Table 5), but such multi-institutional, well-annotated cohorts (e.g., covering rare GI cancer subtypes) are scarce in clinical practice. Smaller datasets (e.g., COBRA’s 3K WSIs) sometimes lead to limited generalization to diverse pathological scenarios[120]. Second, mismatch between model design and patho

Future research on VFMs in GI cancer pathology should target specific limitations. For example, to address data scarcity, it is a priority to develop small-dataset-adaptable VFMs. The H0-mini model success in leveraging 6K WSIs (Table 5) via knowledge distillation from H-Optimus-0[127]. Future models could integrate distillation and cross-stain transfer learning, enabling reliable training even with limited GI cohorts (similar to Virchow2G mini)[115]. Second, to enhance pathological interpretability, designing feature-aligned VFMs is useful. Drawing on Phikon-v2, particularly its biomarker prediction tasks (Supplementary Table 6), future models could link image features to pathological biomarkers (e.g., MSI, HER2, ER in GI tumors), bridging the gap between model outputs and pathologists’ morphological analysis[116]. Third, to improve clinical deployment, optimizing lightweight VFMs for laboratory hardware is critical. Following TissueConcepts’ 27.5M-parameter design (Table 5) and efficient linear-probe fine-tuning (Supplementary Table 6), future research should focus on compressing models to run on standard laboratory workstations, avoiding reliance on large GPU clusters (as needed by larger models like Virchow2 or Phikon-v2)[128]. Finally, to tackle sample variability, training VFMs on heterogeneous pathological datasets is necessary. Models could incorporate augmented data simulating staining inconsistencies and tissue folding, enhancing robustness to real-world GI biopsy variations.

In the preceding overview of endoscopic and radiological imaging, multimodal FMs have been recurrently highlighted (Tables 2 and 3). These models integrate different types of data, like endoscopic images with text, or CT and MRI scans alongside clinical records and genetic information, to yield superior diagnostic and prognostic performance relative to unimodal approaches. For instance, the ColonCLIP model analyzes endoscopic images and reports together, and GPT-4V uses a multimodal approach for radiological image analysis[92,133]. MLLMs are designed to process and integrate diverse data modalities (text, images, etc.), thereby capturing intermodal relationships that facilitate more efficient learning and enhanced predictive accuracy[134]. They work by merging diverse data into a unified representation, extracting key features from each data type (e.g., word embeddings from text or CNN features from images), and subsequently integrating these features through mechanisms like multilayer perceptrons or graph neural networks. Such integrative modeling holds considerable promise in medical contexts, offering comprehensive diagnostic insights that can improve therapeutic strategies for diseases including GI cancers[135].

Table 6 summarizes pivotal studies investigating MLLMs within GI pathology, while Supplementary Table 7 extends this overview by detailing methodological aspects constrained by space in the main table. The Supplementary material elaborates on training datasets, specifying sources and volumes of image-text pairs or WSIs, performance evaluation metrics across various tasks, and the training and fine-tuning protocols employed. Collectively, these resources provide a thorough depiction of the current landscape of MLLMs in GI cancer research, enabling an in-depth examination of their potential applications.

| Model | Year | Vision architecture | Vision dataset | WSIs | Text model | Text dataset | Parameters | Tissues | Generative | Open source link |

| PLIP[136] | 2023 | CLIP | OpenPath | 28K | CLIP | OpenPath | NA | 32 | Captioning | https://github.com/PathologyFoundation/plip |

| HistGen[137] | 2023 | DINOv2, ViT-L | Multiple | 55K | LGH Module | TCGA | Approximately 100M | 32 | Report generation | https://github.com/dddavid4real/HistGen |

| PathAlign[138] | 2023 | PathSSL | Custom | 350K | BLIP-2 | Diagnostic reports | Approximately 100M | 32 | Report generation | https://github.com/elonybear/PathAlign |

| CHIEF[139] | 2024 | CTransPath | 14 Sources | 60K | CLIP | Anatomical information | 27.5M, 63M | 19 | No | https://github.com/hms-dbmi/CHIEF |

| PathGen[140] | 2024 | LLaVA, CLIP | TCGA | 7K | CLIP | 1.6M pairs | 13B | 32 | WSI assistant | https://github.com/PathFoundation/PathGen-1.6M |

| PathChat[141] | 2024 | UNI | Multiple | 999K | LLaMa 2 | Pathology instructions | 13B | 20 | AI assistant | https://github.com/fedshyvana/pathology_mllm_training |

| PathAsst[142] | 2024 | PathCLIP | PathCap | 207K | Vicuna-13B | Pathology instructions | 13B | 32 | AI assistant | https://github.com/superjamessyx/Generative-Foundation-AI-Assistant-for-Pathology |

| ProvGigaPath[143] | 2024 | ViT | Prov-Path | 171K | OpenCLIP | 17K Reports | 1135 | 31 | No | https://github.com/prov-gigapath/prov-gigapath |

| TITAN[144] | 2024 | ViT | Mass340K | 336K | CoCa | Medical reports | Approximately 5B | 20 | Report generation | https://github.com/your-repo/TITAN |

| CONCH[145] | 2024 | ViT | Multiple | 21K | GPTstyle | 1.17M pairs | NA | 19 | Captioning | http://github.com/mahmoodlab/CONCH |

| SlideChat[146] | 2024 | CONCHLongNet | TCGA | 4915 | Qwen2.5-7B | Slide Instructions | 7B | 10 | WSI assistant | https://github.com/uni-medical/SlideChat |

| PMPRG[147] | 2024 | MR-ViT | Custom | 7422 | GPT-2 | Pathology Reports | NA | 2 | Multi-organ report | https://github.com/hvcl/Clinical-grade-PathologyReport-Generation |

| MuMo[148] | 2024 | MnasNet | Custom | 429 | Transformer | PathoRadio Reports | NA | 1 | No | https://github.com/czifan/MuMo |

| ConcepPath[149] | 2024 | ViT-B, CONCH | Quilt-1M | 2243 | CLIPGPT | PubMed | Approximately 187M | 3 | No | https://github.com/HKU-MedAI/ConcepPath |

| GPT-4V[150] | 2024 | Phikon ViT-B | CRC-7K, MHIST etc. | 338K | GPT-4 | NA | 40M | 3 | Report generation | https://github.com/Dyke-F/GPT-4V-In-Context-Learning |

| MINIM[151] | 2024 | Stable diffusion | Multiple | NA | BERT, CLIP | Multiple | NA | 6 | Report generation | https://github.com/WithStomach/MINIM |

| PathM3[152] | 2024 | ViT-g/14 | PatchGastric | 991 | FlanT5XL | PatchGastric | NA | 1 | WSI assistant | NA |

| FGCR[153] | 2024 | ResNet50 | Custom, GastrADC | 3598, 991 | BERT | NA | 9.21 Mb | 6 | Report generation | https://github.com/hudingyi/FGCR |

| PromptBio[154] | 2024 | PLIP | TCGA, CPTAC | 482, 105 | GPT-4 | NA | NA | 1 | Report generation | https://github.com/DeepMed-Lab-ECNU/PromptBio |

| HistoCap[155] | 2024 | ViT | NA | 10K | BERT, BioBERT | GTEx datasets | NA | 40 | Report generation | https://github.com/ssen7/histo_cap_transformers |

| mSTAR[156] | 2024 | UNI | TCGA | 10K | BioBERT | Pathology Reports 11K | NA | 32 | Report generation | https://github.com/Innse/mSTAR |

| GPT-4 Enhanced[157] | 2025 | CTransPath | TCGA | NA | GPT-4 | ASCO, ESMO, Onkopedia | NA | 4 | Recommendation generation | https://github.com/Dyke-F/LLM_RAG_Agent |

| PRISM[158] | 2025 | Virchow, ViT-H | Virchow dataset | 587K | BioGPT | 195K Reports | 632M | 17 | Report generation | NA |

| HistoGPT[159] | 2025 | CTransPath, UNI | Custom | 15K | BioGPT | Pathology Reports | 30M to 1.5B | 1 | WSI assistant | https://github.com/marrlab/HistoGPT |

| PathologyVLM[160] | 2025 | PLIP, CLIP | PCaption-0.8M | NA | LLaVA | PCaption-0.5M | NA | Multi | Report generation | https://github.com/ddw2AIGROUP2CQUP/PA-LLaVA |

| MUSK[161] | 2025 | Transformer | TCGA | 33K | Transformer | PubMed Central | 675M | 33 | Question answering | https://github.com/Lilab-stanford/MUSK |

Starting with model development and architecture, a key trend lies in the integration of vision and language modules, as exemplified by SlideChat (Table 6)[136-161]. This model employs a dedicated vision encoder to process gigapixel WSIs and pairs it with a language model to enable multimodal conversational capabilities. It further notes that SlideChat’s integration design allows it to answer complex GI tissue pathology questions based on WSI input, achieving an overall accuracy of 81.17% on the SlideBench-VQA (TCGA) benchmark[146]. This result not only validates the effectiveness of cross-modality integration but also highlights the need for targeted parameterization and optimization. Many MLLMs in this field, including those detailed in Supplementary Table 7, undergo fine-tuning of their text-component parameters on GI-cancer-specific datasets, a process that adjusts models to better capture features like histological subtypes of gastric cancer, thereby laying a technical foundation for subsequent dataset utilization and clinical applications.

Closely tied to model advancement is the development of dataset utilization, as high-performance MLLMs rely on both diverse and specialized data sources to generalize to real-world GI cancer scenarios. On one hand, models in Table 6 leverage multi-modal datasets combining publicly available GI cancer image repositories and paired pathology reports, textual documents that detail histological features, diagnoses, and even patient clinical histories. These datasets, often containing thousands of image-text pairs, train MLLMs to establish meaningful correlations between tissue visual appearance and textual descriptions, a prerequisite for accurate clinical interpretation. On the other hand, to address unique challenges in GI pathology (such as WSI-specific analysis), specialized datasets have been developed. An example is the PathCap dataset (Supplementary Table 7), which focuses on multi-modal comprehension for pathology[142]. This dataset integrates WSI patches, associated clinical reports, and a rich collection of 207k image-caption pairs designed to simulate real-world diagnostic queries. By leveraging this multimodal dataset, researchers can train models to better understand the complex interplay between visual and textual information, thereby accelerating the translation of advanced AI techniques into actionable clinical insights.

The technical advancements in models and datasets have ultimately driven applications of MLLMs in GI cancer diagnosis and prognosis. In diagnosis, MLLMs excel at identifying distinct GI cancer types by linking histological image patterns to text-based diagnostic criteria, which notes that several models can distinguish or predict EBV or HER2-positive gastric cancer subtypes (MuMo[148] or ConcepPath[149] respectively). Beyond diagnosis, MLLMs are also advancing prognosis prediction by integrating multi-source data. They extract histological features from images and combine them with patient-specific information from text reports (e.g., tumor stage, grade, molecular markers). Findings suggest these multimodal prognostic models offer more comprehensive and accurate predictions than traditional methods relying solely on single-modality data, reflecting the synergistic progress of MLLMs across model design, data curation, and clinical translation in GI cancer pathology (e.g., CHIEF[139], PathGen[140], MuMo[148]).

Despite their progress, current MLLMs in GI cancer pathology also face distinct limitations. First, data dependence and scarcity hinder generalization, limiting a model's ability to perform well on diverse datasets due to insufficient training data. Models like PathM3 (Table 6) rely on only 991 WSIs from the PatchGastric dataset[152], while MuMo uses a mere 429 WSIs, small sample sizes that risk overfitting to specific tissue types or institutions[148], unlike larger-scale models such as PathChat (999K WSIs) which have broader but still non-representative datasets lacking diverse clinical settings[141]. Second, limited model accessibility and transparency pose barriers to widespread adoption and trust due to restricted availability and unclear operational mechanisms. Models including PRISM[158] and PathM3[152] lack open-source links, preventing independent validation by other researchers (Table 6). Even open models like CHIEF require 8 V100 GPUs (Supplementary Table 7), a resource beyond many clinical labs[139]. Finally, current models are sometimes designed for specific tasks, making them less useful for broader or more varied needs. Several models (e.g., HistGen[137], CONCH[145], FGCR[153]) focus solely on report generation, converting WSI features into text without supporting diagnostic or prognostic assistance. Only 3 out of 26 models (e.g., MUSK[161]) support question-answering for rare GI cancer subtypes. Five models (e.g., CHIEF[139], ConcepPath[149]) are explicitly non-generative, performing only basic tasks like classification and unable to address complex clinical needs such as report interpretation or treatment suggestions.

Future research on MLLMs in GI cancer pathology could improve current weaknesses by making better use of the models’ hidden potential and tackling key missing capabilities. For example, it is possible to enhance the model's ability to perform a broader range of clinical tasks, enabling it to support diverse applications such as diagnosis assistance, prognosis prediction and treatment recommendation. Second, it could enhance the diversity, quality, and clinical relevance of training data by including a broader range of patient demographics, cancer subtypes (including rare forms), disease stages, and multimodal information to ensure models generalize well across real-world clinical scenarios. Third, it could be helpful to improve the integration of these models with real-world clinical workflows by ensuring their outputs are not only accurate and interpretable but also actionable and relevant to practical needs.

This review retrospectively summarizes some key and representative studies concerning the application of FMs in GI cancer research. Given that many artificial intelligence terms (e.g., zero-shot learning, black-box problem) may not be familiar to medical researchers, we summarized Supplementary Table 8 to define key terms used in this review for improved clarity. Due to inherent limitations in literature search and screening, it is acknowledged that some studies may not have been included. Although numerous investigations have already shown that FMs have considerable potential in this domain, there are still some challenges in using them and bringing them into clinical practice. For example, medical imaging and pathology data often have different formats and standards across institutions. This makes it hard for models to work well in different settings, especially in studies done at just one center[162]. Furthermore, publication bias remains a concern, whereby studies reporting positive outcomes are preferentially published, whereas negative or inconclusive results often remain unpublished, thereby skewing the overall scientific evidence base.

The extant evidence supporting the use of FMs in GI oncology is constrained by several methodological and practical limitations. First, with respect to data privacy and security, FMs typically necessitate large-scale datasets to achieve optimal performance, which inherently increases the risk of data breaches and unauthorized access[163]. Conventional de-identification techniques are increasingly insufficient, especially when integrating multimodal data types such as imaging, genomics, and EHRs, which may facilitate re-identification. To mitigate these risks, the incorporation of privacy-preserving technologies into model development is imperative[164]. Approaches such as federated learning enable model training across multiple institutions without sharing raw data, effectively shifting the model rather than the data. Differential privacy techniques introduce controlled noise during training to safeguard individual identities, while blockchain technology offers immutable systems for tracking data access and consent. Ensuring global compliance necessitates governance frameworks aligned with regulations such as the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), thereby promoting secure and ethical data utilization.

Second, regarding model interpretability and clinical trust, FMs often function as "black boxes", with limited transparency in their decision-making processes, even to developers and end-users[165]. This lack of transparency can undermine clinician and patient confidence, as clear explanations for model-driven recommendations (e.g., the rationale for classifying a polyp as malignant) are typically required. Although explainable AI (XAI) tools such as Grad-CAM (for imaging models), SHAP, and LIME exist, their application within FMs remains limited and predominantly provides correlational rather than causal insights[166]. For example, Grad-CAM can highlight regions of interest in endoscopic images but does not elucidate causal relationships, such as why a specific genetic mutation influences treatment response predictions. This discrepancy highlights a critical gap between clinical needs for causal explanations and the correlational outputs currently provided by FMs. Bridging this gap necessitates the development of clinician-centric visualization interfaces that link model predictions to specific clinical features, including polyp size or histological characteristics. Interpretability should be regarded as a core performance metric alongside accuracy and sensitivity in FM validation studies, rather than an ancillary consideration. Additionally, integrating principles from human factors engineering into FM design can ensure that explanations align with clinical workflows and cognitive demands, thereby fostering greater acceptance.

Third, respecting bias and equity, many FM training datasets predominantly originate from high-income countries and large academic centers, resulting in the underrepresentation of minority populations and low-resource settings[167]. This imbalance introduces biases that may exacerbate health disparities. For example, existing studies so far have largely focused on specific groups of patients, like those from Asia or Europe/the United States, potentially limiting model ap

As regards regulatory pathways, current frameworks for medical AI are inadequately suited to FMs, which differ from traditional tools in their generalizability and capacity for continuous learning from new data[168]. Regulatory pathways such as the United States FDA’s De Novo classification and 510(k) clearance have been applied to certain AI-based diagnostic tools, such as the FDA-approved Paige Prostate software for identifying cancer cells in prostate pathology images[109]. However, FMs, which can be adapted for multiple tasks (e.g., CRC detection, chemotherapy response prediction, and high-risk patient identification), do not conform to these static, task-specific approval models. Con

Finally, in regard to clinical validation and real-world deployment, most FM studies remain confined to technical validation phases, demonstrating high accuracy under controlled conditions[170]. However, such findings do not necessarily translate into clinical utility, defined by improvements in diagnosis, treatment decision-making, or patient outcomes. Operational feasibility, including seamless integration into existing clinical workflows without imposing additional burdens on healthcare providers, is infrequently evaluated. Moreover, cost-effectiveness analyses, such as whether FMs predicting chemotherapy response reduce unnecessary treatment expenditures, are scarce. Addressing these gaps requires rigorous, multicenter, prospective randomized controlled trials. Implementation science research should investigate FM performance across diverse healthcare systems and resource settings. Enhancing transparency through the establishment of public clinical trial registries, where study protocols, data, and outcomes are openly accessible, is also advocated.

In summary, FMs possess transformative potential for GI cancer care, ranging from facilitating early detection to enabling personalized therapeutic strategies. Nonetheless, technological advancements alone are insufficient for successful clinical translation. Addressing technical limitations alongside ethical, regulatory, and equity-related challenges is imperative. The future role of FMs in GI oncology is not to supplant clinicians but to augment precision medicine. It's important to recognize that both presently and prospectively, FMs and related tools will not replace endoscopists, radiologists, or pathologists. The main role of models lies in providing professional analytical support, while the final diagnosis and treatment decisions will still be led by clinicians. This partnership between humans and machines will continue to be key to helping patients.

| 1. | Bray F, Laversanne M, Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2024;74:229-263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5690] [Cited by in RCA: 12617] [Article Influence: 6308.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |