Published online Dec 21, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i47.111637

Revised: July 30, 2025

Accepted: November 7, 2025

Published online: December 21, 2025

Processing time: 167 Days and 22.3 Hours

Hepatitis delta virus (HDV) infection is the most severe form of chronic viral hepatitis, yet sex-based clinical differences remain poorly defined. Understanding these differences may inform disease management and guide research.

To investigate sex-related differences in demographic and clinical characteristics of patients with chronic HDV infection in a nationwide, real-world Italian setting.

We analyzed demographic, clinical, and virological data from 513 hepatitis B surface antigen/anti-HDV-positive patients, consecutively enrolled between 2019 and 2024, across 58 liver clinics in the Italian PITER HDV cohort. A propensity score-weighted logistic regression model evaluated the association between sex and cirrhosis and/or hepatocellular carcinoma.

Among 513 patients (61.6% male), median age (56.0 years) and age distribution were similar by sex (P = 0.41). Cirrhosis was frequent: 73.4% vs 66.0% (anti-HDV-positive) and 77.8% vs 74.2% (HDV RNA-positive) in males and females, respectively. HDV RNA levels were comparable (P = 0.93). The highest proportion of females with cirrhosis (33.8%) was in the 56-60-year group, similar to males (34.9%). Among patients with cirrhosis aged ≤ 40 years, females, (80.9% of whom of non-Italian origin), were more represented than males (16.1% vs 6.5% respectively, P < 0.05). Male sex was associated with cirrhosis (odds ratio = 1.85; 95% confidence interval: 1.004-3.40). Among HDV RNA-positive patients, males more often had hepatocellular carcinoma, elevated gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase, alcohol use, diabetes, hypertension, steatotic liver disease, and hepatitis C virus/human immunodeficiency virus coinfection. Interferon eligibility was similar.

HDV-infected females develop cirrhosis earlier, without liver disease cofactors, while males show advanced liver disease with multiple cofactors. Tailored care for young migrant women and cofactor-guided management for men may improve HDV outcomes, promoting equity.

Core Tip: This multi-centre study analyzed 513 patients with chronic hepatitis delta virus (HDV) infection, enrolled across 58 Italian liver clinics regardless of treatment eligibility. The study population reflects the current HDV epidemiology in Italy, including a high proportion of migrant women. Key sex-based differences emerged: Men had a greater burden of metabolic comorbidities and hepatocellular carcinoma, while women, particularly those born abroad, were more likely to develop cirrhosis not only after menopause, as seen in other chronic viral liver diseases, but also at significantly young ages, including those younger than 40 years of age. Tailored care for young migrant women, unvaccinated against hepatitis B virus, and cofactor-guided management for men may improve liver disease outcomes.

- Citation: Coco B, Quaranta MG, Tosti ME, Ferrigno L, Brancaccio G, Ciancio A, Coppola C, Messina V, Gentile I, Claar E, Morisco F, Santantonio T, Viganò M, Cacciola I, Pompili M, Russo FP, Izzi A, Niro GA, Coppola N, Soria A, Federico A, Morsica G, Puoti M, Villa E, Lampertico P, Gaeta GB, Kondili LA, Brunetto MR, PITER Collaborating Investigators. Sex-based differences in hepatitis delta virus infection: Insights from the Italian PITER hepatitis delta virus cohort. World J Gastroenterol 2025; 31(47): 111637

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v31/i47/111637.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i47.111637

Chronic viral hepatitis remains a major global cause of liver-related morbidity and mortality[1-3]. Increasing evidence highlights sex as a critical determinant in the progression and outcomes of these infections, shaping biological susceptibility, age, transmission mode, and also healthcare access and provider response. These differences contribute to disparities in diagnosis, treatment, and outcomes between men and women[4].

In both hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hepatitis C virus (HCV) infections, sex differences influence the clinical course[4-6]. In particular, the protective effects observed in women diminish after menopause, contributing to accelerated liver fibrosis progression in older age[7]. Antiviral response is also modulated by sex, particularly in HCV, where postmenopausal women exhibit reduced sustained virological response to interferon (IFN)-based therapy, likely due to hormonal decline and more advanced liver disease at treatment initiation[8]. In contrast, the influence of sex on hepatitis delta virus (HDV) infection, the most severe form of chronic viral hepatitis, remains poorly understood. Given HDV’s highly aggressive nature and its rapid progression to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), elucidating sex-related differences in disease trajectories is essential, particularly in light of emerging therapeutic options[9,10].

This study aimed to investigate sex-based differences in the demographic, clinical, and virological profiles of patients with chronic HDV infection enrolled in the Italian multi-centre PITER HBV/HDV cohort. Specifically, we evaluated whether sex is independently associated with disease severity (cirrhosis and/or HCC) and explored its interplay with age, comorbidities, and viral markers, which may help inform more personalized and equitable approaches to HDV care.

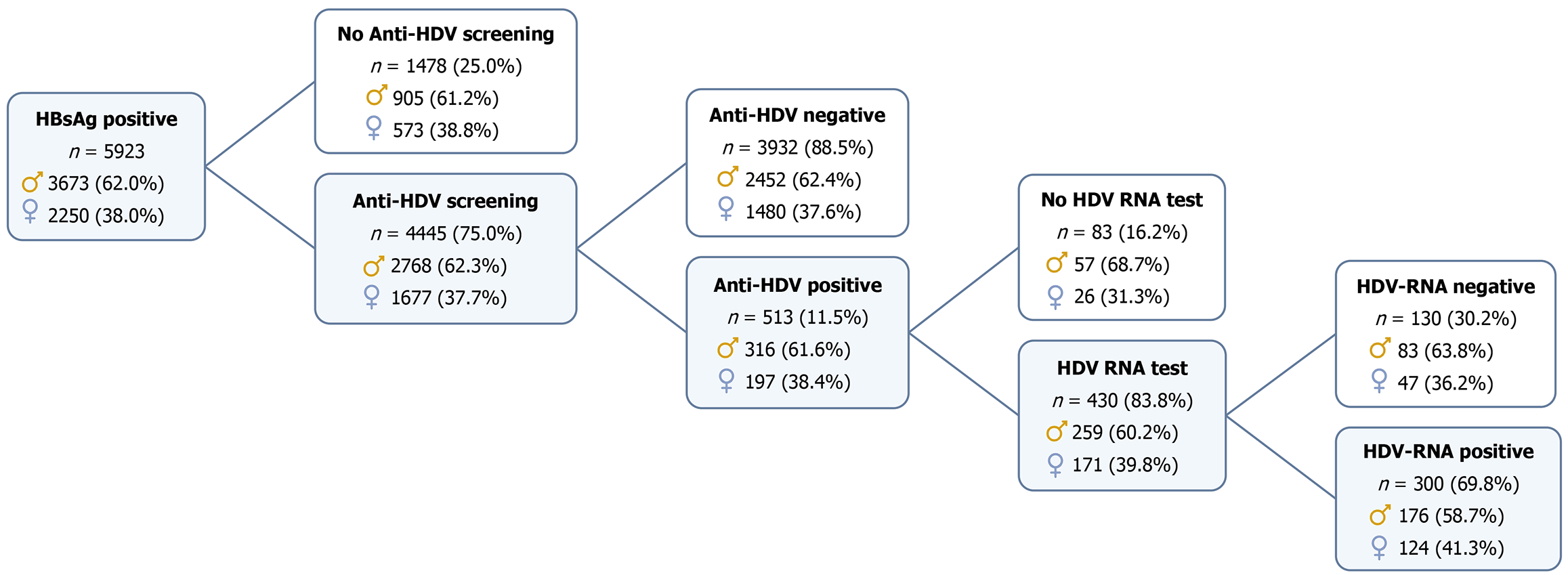

This study analyzed cross-sectional baseline data from the PITER HBV/HDV cohort, comprising 5923 hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)-positive patients (aged older than 18 years), consecutively enrolled at 58 Italian referral centres between November 2019 and March 2024. A detailed flow chart outlining the inclusion of patients in this study is provided in Figure 1. Of those screened for HDV (n = 4445; 75% of males, 74.5% of females), 513 anti-HDV-positive patients with complete demographic (age, sex) and core clinical data (cirrhosis staging and HCC diagnosis) were included in the sex-based analysis. Patients without anti-HDV testing, as well as those who tested negative for anti-HDV, were excluded from the analytical cohort. However, for comparative purposes, the prevalence of cirrhosis by age and sex was assessed among HBV-monoinfected individuals (i.e., anti-HDV negative) within the broader HBsAg-positive population of the PITER cohort, based on enrollment (baseline) data.

Demographic, clinical, and laboratory data were collected at enrolment via a standardized electronic case report form. Cirrhosis was diagnosed by liver histology (Metavir ≥ F4/Ishak ≥ 6), transient elastography [liver stiffness measurements (LSM) > 12.5 kPa], or imaging/clinical signs of portal hypertension. LSM was considered valid if ≥ 10 measurements had a success rate of ≥ 80%, an interquartile range (IQR) of < 30%, and a body mass index (BMI) of < 30 kg/m2. Liver disease severity was evaluated using the child-Pugh and model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) scores as surrogate markers of hepatic dysfunction. These scoring systems were originally developed for prognostic evaluation but are commonly applied in cross-sectional studies to stratify patients according to the degree of liver functional impairment, without implying predictive intent[11]. In this study, they were used solely to support clinical phenotyping and to describe the severity of hepatic dysfunction at enrollment, including assessment of hepatic functional reserve and the potential presence of portal hypertension, as suggested by clinical and laboratory findings, such as thrombocytopenia[12-14].

Cofactors and comorbidities, potentially related to liver disease progression, included alcohol use, injection drug use, diabetes, hypertension, dyslipidemia, overweight/obesity, and steatosis (diagnosed by ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging, or biopsy). Steatotic liver disease (SLD) was defined according to the European Association for the Study of the Liver-European Association for the Study of Diabetes-European Association for the Study of Obesity guidelines[15]. Extrahepatic comorbidities, including those contraindicating IFN therapy, were also evaluated. Among HDV RNA-positive patients, potential eligibility for IFN-based therapy was evaluated based on medical contraindications, excluding considerations of treatment adherence or patient willingness, as previously described[9].

Routine serological and virological testing, including HBsAg, hepatitis B e antigen/anti-hepatitis B e antigen, and anti-HDV, anti-HCV, and anti-human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) antibodies, was performed using commercial enzyme immunoassays. When indicated, HCV RNA and HIV RNA were measured using standard assays.

Quantitative HDV RNA was assessed using the RoboGene HDV RNA quantification kit 2.0 (limit of detection =

The analysis examined sex-related differences among HBsAg/anti-HDV-positive patients and in those HDV RNA-positive. To ensure data integrity while reflecting the observational nature of the study, only patients with complete core demographic, virological, and clinical data relevant to the study objectives (including age, sex, cirrhosis status, and HCC diagnosis) were included in the analyses, even when some secondary clinical or laboratory parameters were incomplete or missing. No imputation procedures were applied. Proportions are based on available data, and totals may differ due to missing values. Continuous variables were reported as medians with IQRs, categorical variables as counts and percentages. Clinically relevant cut-offs for platelet count (≤ 150000 μL), child-Pugh class (A vs B and C), and MELD score (≥ 20) were used to describe the liver disease severity of the enrolled patients. Comparisons between groups were performed using χ² or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables, and the Mann-Whitney U test for continuous variables. The association between sex and the selected outcome (cirrhosis and/or HCC) was evaluated by odds ratios (ORs) and its 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

To control for confounding due to baseline differences between males and females, we applied a propensity score-based inverse probability weighting (IPW) method[16,17]. The propensity score, defined as the probability of being male (vs female) given the observed covariates, was estimated using a probit regression model, which is suitable for the binary nature of the exposure variable (sex). Covariates included in the model were: Age, BMI category, HDV RNA status, HBV DNA detectability, history of IFN therapy, duration of nucleos(t)ide analogue (NUC) therapy, alcohol use, diabetes, and presence of SLD. The quality of the balancing procedure was evaluated using standardized mean differences, with values < 0.10 indicating adequate balance. Following IPW adjustment, a logistic regression model was applied to assess the independent association of sex with cirrhosis and/or HCC. Statistical significance was evaluated using the Wald test with a two-sided P value. P values < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were conducted using STATA version 16.1 (StataCorp, College Station, TX, United States).

The main characteristics of the study population, categorized by sex, are presented in Table 1. Among the 513 HBsAg/anti-HDV-positive patients (none of whom were on bulevirtide treatment at enrollment), 316 (61.6%) were male and 197 (38.4%) were female. Median age was 56.0 years for both sexes (P = 0.41). Non-Italian origin (33.7%) was significantly more common among females (46.7%) than among males (25.6%, P < 0.001), with most foreign-born patients coming from Central and Eastern Europe, followed by sub-Saharan Africa and Asia (detailed demographic and clinical characteristics by nationality are reported in Supplementary Table 1).

| Anti-HDV positive | P value | ||

| Males | Females | ||

| 3161 (61.6) | 1971 (38.4) | 0.738 | |

| Age, median (Q1-Q3) | 56 (48-63) | 56 (45-62) | 0.409 |

| ≤ 40 | 35 (11.1) | 37 (18.8) | 0.143 |

| 41-50 | 59 (18.7) | 38 (19.3) | |

| 51-60 | 114 (36.1) | 58 (29.4) | |

| 61-70 | 85 (26.9) | 50 (25.4) | |

| > 70 | 23 (7.3) | 14 (7.2) | |

| Non-Italian natives | 81 (25.6) | 92 (46.7) | < 0.001 |

| Injection drug use (any time) | 45 (17.3) | 3 (1.7) | < 0.001 |

| ALT > 35 IU/L | 199 (64.8) | 108 (56.5) | 0.065 |

| GGT > 50 IU/L | 116 (46.6) | 44 (27.3) | < 0.001 |

| HBeAg positive | 16 (5.3) | 12 (6.3) | 0.612 |

| HDV RNA positive (n = 430 tested) | 176 (68.0) | 124 (72.5) | 0.314 |

| Cirrhosis | 232 (73.4) | 130 (66.0) | 0.073 |

| Child-Pugh class | |||

| A | 197 (86.8) | 103 (82.4) | 0.231 |

| B | 25 (11.0) | 21 (16.8) | |

| C | 5 (2.2) | 1 (0.8) | |

| MELD ≥ 20 | 6 (3.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.097 |

| HCC | 40 (12.6) | 11 (5.6) | 0.010 |

| PLT ≤ 150000 | 177 (57.8) | 108 (56.5) | 0.776 |

| Previous IFN | 104 (35.4) | 49 (27.7) | 0.084 |

| Cofactors of liver disease | |||

| BMI 25-30 | 84 (37.8) | 45 (33.1) | 0.124 |

| BMI ≥ 30 | 19 (8.6) | 21 (15.4) | |

| Ongoing alcohol use | 61 (23.0) | 10 (6.1) | < 0.001 |

| Past use | 58 (21.9) | 15 (9.2) | |

| Diabetes | 28 (8.9) | 4 (2.0) | 0.002 |

| Steatotic liver disease | 84 (26.6) | 36 (18.3) | 0.031 |

| Anti-HCV positive (all HCV RNA negative) | 42 (14.7) | 1 (0.6) | < 0.001 |

| Anti-HIV positive | 22 (8.1) | 1 (0.6) | 0.001 |

| NUC treatment | |||

| Ongoing NUC therapy | 234 (74.3) | 138 (70.4) | 0.338 |

| Years of NUC therapy, median (Q1-Q3) | 4.2 (1.7-7.9) | 4.2 (2.0-7.6) | 0.733 |

Cirrhosis affected over 70% of patients, with a slightly higher, but not statistically significant, prevalence in males (73.4%) than females (66.0%, P = 0.073). Thrombocytopenia (platelet count ≤ 150000/μL) affected 55.5% of the patient population, with no sex differences. Elevated gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT) was more frequent in males (46.6% vs 27.3%, P < 0.0001), suggesting greater biochemical liver injury. Alanine transaminase (ALT) elevation was higher in men, with a non-significant, but borderline statistically significant difference (P = 0.065), which may still reflect clinically relevant trends in hepatocellular injury between the sexes (Table 1). HCC was diagnosed in 9.8% of patients with a significantly higher rate in males (12.6%) compared to females (5.6%, P = 0.01). Most patients were on NUC therapy at enrolment (72.5%), with similar proportions by sex and median treatment duration of 4.2 years (Table 1).

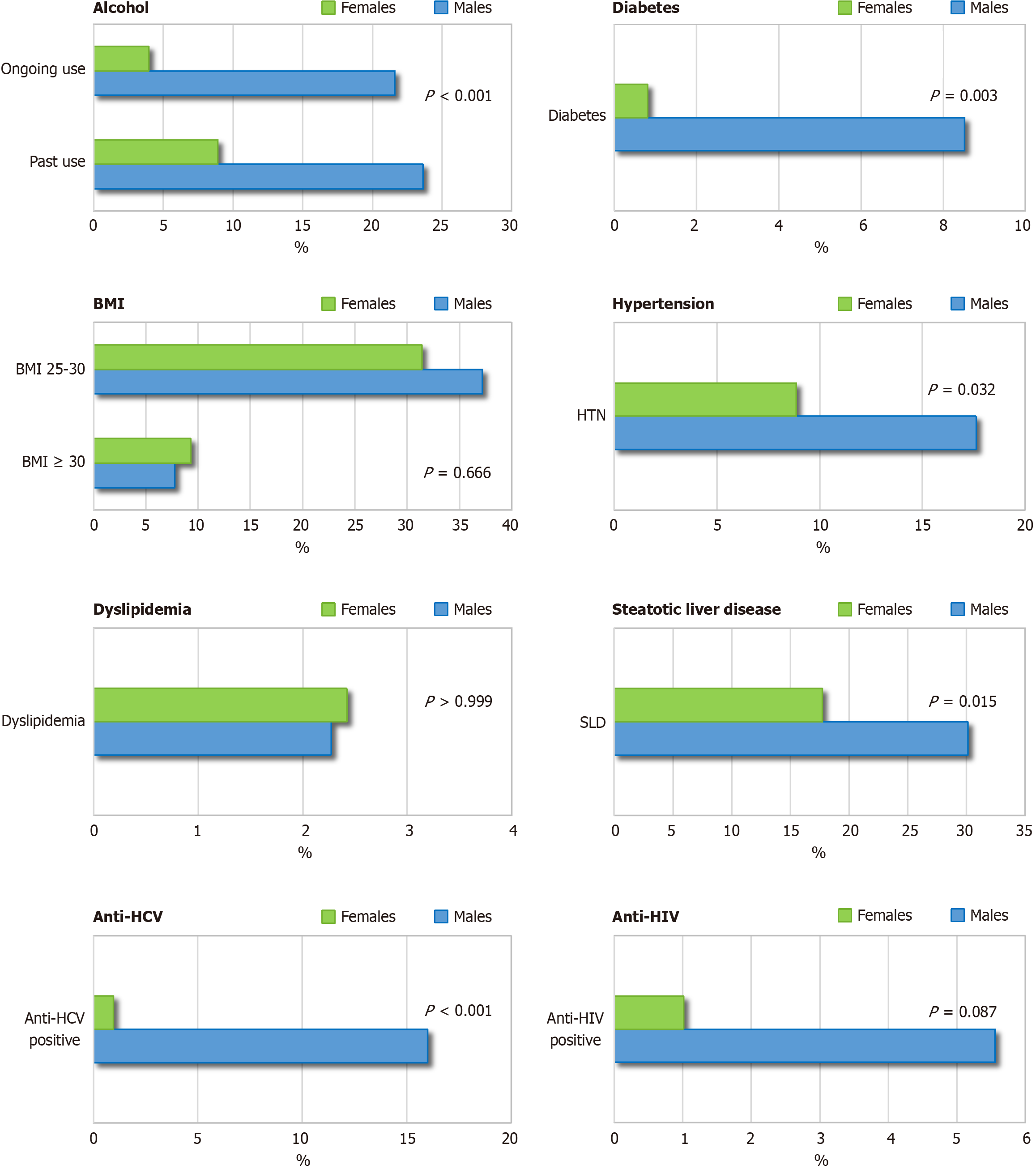

As shown in Table 1, behavioral risk factors were significantly more prevalent in males, including injection drug use, alcohol consumption, and co-infection with HCV or HIV (all P ≤ 0.001). Males also showed higher rates of diabetes (P = 0.002) and SLD (P = 0.031). Obesity was more frequent in females (15.4% vs 8.6%), but the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.124) (Table 1). Among those with SLD, alcohol use was significantly more frequent in males (39 out of 84; 46.4%) than in females (4 out of 36; 11.1%) (P = 0.001).

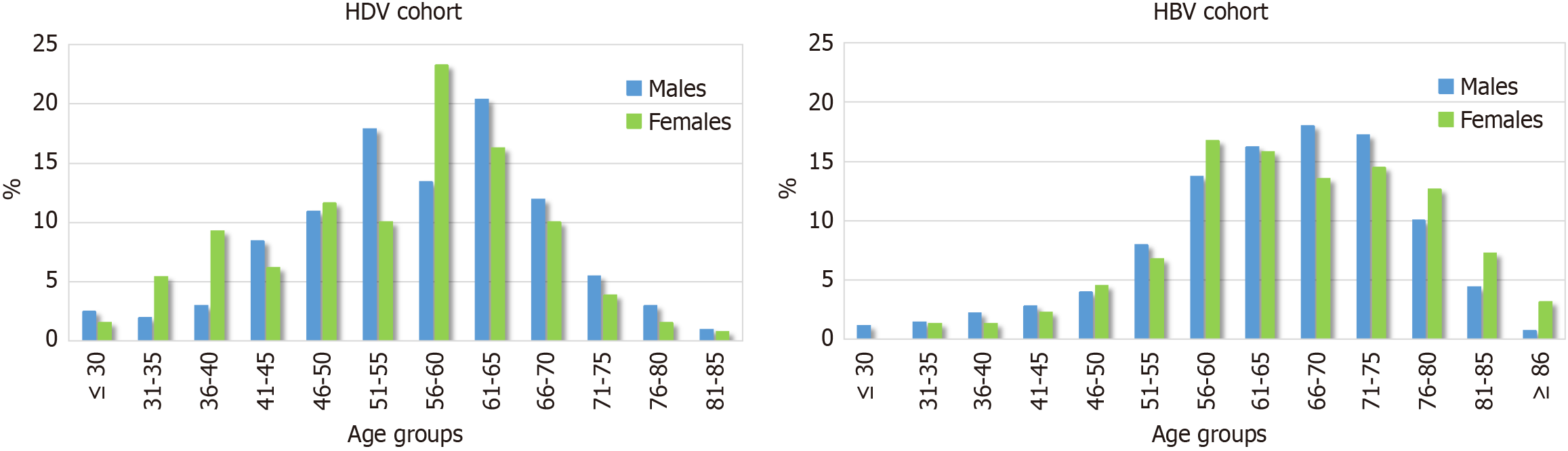

Sex-specific age distribution patterns and demographic and clinical characteristics among patients with cirrhosis (n = 362; 64.1% male) are summarized in Table 2 and Figure 2. Among these patients, non-Italian origin was significantly more common in females than in males (40.8% vs 23.7%; P = 0.001). Most patients with cirrhosis in both sexes (59.9% of males and 67.7% of females) were younger than 61 years. Among females with cirrhosis, the highest proportion (33.8%) was in the 56-60-year age group, closely matching that of males (34.9%) (Table 2 and Figure 2). However, in the ≤ 40-year age group, a significantly higher proportion of females were observed compared to males (16.1% vs 6.5%, P = 0.003); 80.9% of these younger females were of non-Italian origin.

| Characteristics | F4/cirrhosis | P value | |

| Males (n = 2321) | Females (n = 1301) | ||

| Age, median (Q1-Q3) | 57 (50-64) | 57 (46-62) | 0.163 |

| ≤ 40 | 15 (6.5) | 21 (16.1) | 0.052 |

| 41-50 | 43 (18.5) | 23 (17.7) | |

| 51-60 | 81 (34.9) | 44 (33.8) | |

| 61-70 | 73 (31.5) | 34 (26.1) | |

| > 70 | 20 (8.6) | 8 (6.1) | |

| Non-Italian natives | 55 (23.7) | 53 (40.8) | 0.001 |

| Injection drug use (any time) | 31 (16.4) | 3 (2.6) | < 0.001 |

| Liver biopsy (any time) | 58 (30.2) | 30 (28.0) | 0.693 |

| ALT > 35 IU/L | 152 (67.9) | 83 (65.3) | 0.632 |

| GGT > 50 IU/L | 101 (55.8) | 40 (38.1) | 0.004 |

| HBeAg positive | 10 (4.5) | 9 (7.2) | 0.289 |

| HDV-RNA tested | 193 (83.2) | 114 (87.7) | 0.252 |

| HDV-RNA positive | 137 (71.0) | 92 (80.7) | 0.059 |

| HDV RNA, median (Q1-Q3) | 95614 (3096-1000000) | 34563 (3971-377359) | 0.932 |

| Child-Pugh class | |||

| A | 197 (86.8) | 103 (82.4) | 0.231 |

| B | 25 (11.0) | 21 (16.8) | |

| C | 5 (2.2) | 1 (0.8) | |

| MELD ≥ 20 | 6 (3.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0.097 |

| HCC | 38 (16.5) | 11 (8.6) | 0.036 |

| PLT ≤ 150000 | 166 (74.1) | 100 (78.7) | 0.330 |

| Previous IFN | 75 (34.6) | 35 (29.7) | 0.362 |

| Cofactors of liver disease | |||

| Ongoing alcohol use | 39 (19.8) | 3 (2.6) | < 0.001 |

| Past use | 50 (25.4) | 11 (9.6) | |

| BMI 25-30 | 61 (38.4) | 27 (31.0) | 0.385 |

| BMI ≥ 30 | 15 (9.4) | 12 (13.8) | |

| Diabetes | 22 (9.5) | 2 (1.5) | 0.004 |

| Steatotic liver disease | 63 (27.2) | 23 (17.7) | 0.042 |

| Anti-HCV positive (all HCV RNA negative) | 33 (15.9) | 1 (0.9) | < 0.001 |

| anti-HIV positive | 14 (7.1) | 1 (1.0) | 0.024 |

| NUC treatment | |||

| Ongoing NUC therapy | 186 (80.5) | 102 (79.1) | 0.742 |

| Years of NUC therapy, median (Q1-Q3) | 4.8 (1.5-8.2) | 4.3 (2.1-7.7) | 0.683 |

Patients with HBV mono infection enrolled in the PITER HBV cohort during the same period had a significantly lower overall prevalence of cirrhosis compared to HDV-coinfected patients (24.1% vs 70.6%, P < 0.001; specific data from the HBV cohort are not shown). Among HBV-mono infected individuals (PITER HBV cohort), cirrhosis was more prevalent in males than females (28.0% vs 15.6%, P < 0.001), yet in both sexes it occurred predominantly after the age of 55. This pattern contrasts with the earlier onset and more aggressive liver involvement observed in HDV coinfection, which disproportionately affects younger individuals, particularly females of non-Italian origin (Figure 2).

Of the 513 anti-HDV-positive individuals, 430 (83.8%) were tested for HDV RNA. Testing rates were similar in males and females, with 18% of males and 13% of females remaining untested (P = 0.148). Among those tested, HDV RNA was detectable in 68.0% of males and 72.5% of females (P = 0.314) (Table 1).

Demographic and clinical characteristics of HDV-RNA-positive patients, stratified by sex, are presented in Table 3. Notably, among participants aged 40 years or younger, females were more frequently represented than males (23.4% vs 13.1%), and this was the only age group in which females outnumbered males. HDV RNA levels were comparable between sexes (P = 0.932) (Table 3), irrespective of nationality (Supplementary Table 1) or cirrhosis status (Table 2).

| Characteristics | HDV-RNA positive | P value | |

| Males (n = 1761) | Females (n = 1241) | ||

| Age, median (Q1-Q3) | 55 (46.5-63) | 56 (43.5-62.5) | 0.599 |

| ≤ 40 | 23 (13.1) | 29 (23.4) | 0.226 |

| 41-50 | 37 (21.0) | 23 (18.5) | |

| 51-60 | 54 (30.7) | 31 (25.0) | |

| 61-70 | 48 (27.3) | 31 (25.0) | |

| > 70 | 14 (7.9) | 10 (8.1) | |

| Non-Italian natives | 55 (31.2) | 65 (52.4) | < 0.001 |

| HDV RNA, median (Q1-Q3) | 66457 (1720-669213) | 50739 (4060.9-372159) | 0.932 |

| ALT > 35 IU/L | 138 (81.2) | 87 (73.1) | 0.104 |

| GGT >50 IU/L | 79 (57.7) | 33 (34.0) | < 0.001 |

| HBeAg positive | 8 (4.7) | 9 (7.6) | 0.316 |

| Cirrhosis | 137 (77.8) | 92 (74.2) | 0.464 |

| Child-Pugh class | |||

| A | 119 (87.5) | 77 (88.5) | > 0.999 |

| B | 16 (11.8) | 10 (11.5) | |

| C | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| MELD ≥ 20 | 3 (2.6) | 0 (0.0) | 0.284 |

| HCC | 31 (17.9) | 7 (5.8) | 0.002 |

| PLT ≤ 150000 | 103 (61.3) | 76 (63.9) | 0.660 |

| Previous IFN | 64 (39.5) | 33 (30.0) | 0.108 |

| NUC treatment | |||

| Ongoing NUC therapy | 137 (78.3) | 90 (73.2) | 0.308 |

| Years of NUC therapy, median (Q1-Q3) | 4.1 (1.6-7.4) | 4.2 (2.1-7.2) | 0.653 |

ALT elevations were similarly distributed between sexes, while GGT abnormalities were significantly more common in males (57.7%) than females (34.0%, P < 0.001). Cirrhosis was present in 76.3% of HDV RNA-positive patients, with no sex difference (77.8% males vs 74.2% females). Child-Pugh class and thrombocytopenia rates were comparable between groups (P > 0.05). In contrast, HCC prevalence among viremic patients was significantly higher in males (17.9%) than in females (5.8%, P = 0.002) (Table 3).

Among HDV RNA-negative patients (n = 130), cirrhosis was still common (n = 78, 60.0%), especially in males (67.5% vs 46.8.% in females; P = 0.02). HCC was diagnosed in 6 HDV RNA-negative males and one HDV RNA-negative female (Supplementary Table 2). Among viremic patients, the detectability of HBV DNA did not differ by sex, regardless of NUC therapy (Supplementary Table 3).

After adjustment for covariates through propensity score weighting and excluding patients with HCV and/or HIV coinfection, male sex remained independently associated (OR = 1.85; 95%CI: 1.004-3.40) with the presence of cirrhosis and/or HCC in chronic HDV infection (Table 4).

| Balanced variables | Unweighted (std-diff) | Weighted (std-diff) | P value |

| Age (Ref. ≤ 55 years) | 0.1229701 | -0.0728242 | |

| HDV-RNA (Ref. neg) | 0.1365088 | -0.013608 | |

| HBV DNA (Ref. neg) | 0.0022074 | -0.0190112 | |

| Previous IFN (Ref. no IFN) | 0.0422737 | -0.0327822 | |

| Years of NUC therapy (continuous variable) | -0.077061 | 0.0570684 | |

| Alcohol use (Ref. no alcohol) | -0.6436189 | 0.0261042 | |

| Diabetes (Ref. no diabetes) | -0.1993716 | -0.0714145 | |

| BMI 25-30 (Ref. < 25) | -0.0935022 | -0.0181635 | |

| BMI ≥ 30 (Ref. < 25) | 0.0949776 | -0.0145787 | |

| Multivariable analysis | OR | 95%CI | |

| Sex (Ref. female) | 1.85 | 1.004-3.40 | 0.048 |

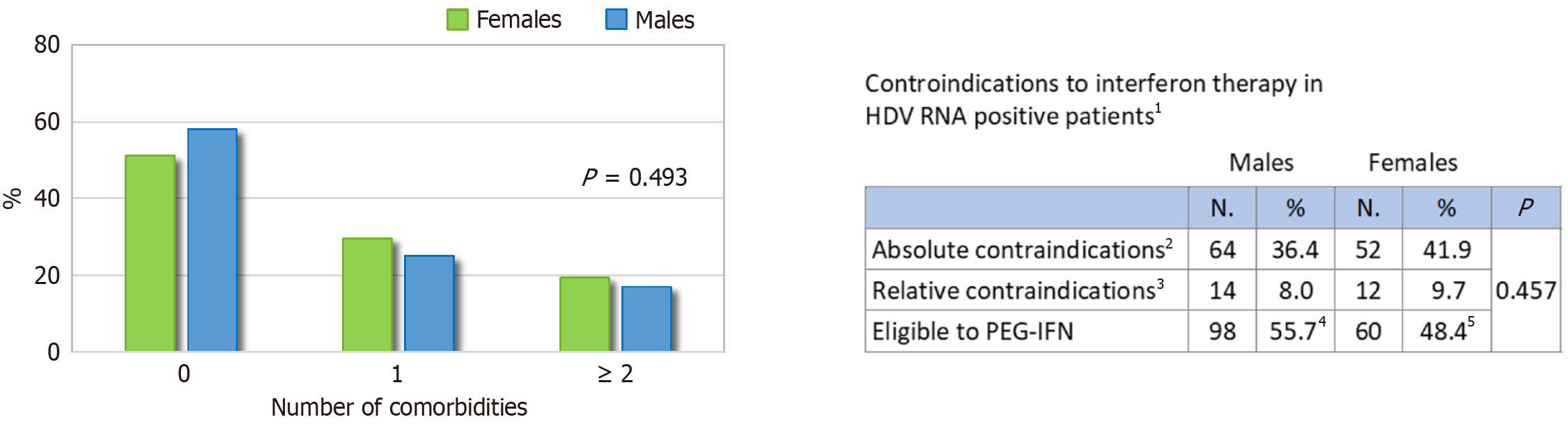

The comorbidity profile of patients with active infection, according to sex, is shown in Figure 3, and the respective absolute values are reported in Supplementary Table 4. Males had a significantly higher prevalence of key cofactors associated with liver disease progression: Alcohol use (P < 0.001), diabetes (P = 0.003), hypertension (P = 0.032), SLD (P = 0.015), and HCV coinfection (P < 0.001). HIV coinfection was more common in males, although the difference was not statistically significant (P = 0.087). Rates of overweight/obesity and dyslipidemia were similar. At least one comorbidity was present in 48.4% of males and 41.9% of females with active HDV infection (Figure 4). Among 300 patients with active infection, 52.7% were potentially eligible for IFN-based therapy, with no significant sex differences (55.7% of males vs 48.4% of females; P = 0.45). Absolute contraindications were present in 36.4% of males and 41.9% of females, while relative contraindications were reported in 8.0% and 9.7%, respectively (Figure 4).

Sex-specific characteristics in HDV infection remain underexplored in the literature[18]. Our analysis of 513 HBsAg/anti-HDV-positive individuals consecutively enrolled in the Italian multi-centre PITER HBV/HDV cohort (2019-2024) addresses this gap, providing a detailed overview of the evolving epidemiological and clinical landscape. This multi-centre study analyzed 513 patients with chronic HDV infection, enrolled across 58 Italian liver clinics, regardless of treatment eligibility[9]. Key sex-based differences emerged: Men exhibited a higher burden of metabolic comorbidities and HCC, whereas women, especially those born abroad, were more likely to develop cirrhosis not only after menopause, as observed in other chronic viral liver diseases, but also from a notably younger age, with cases emerging even before 40 years[4,5,7].

Notably, among patients under 40 years of age, only 2.1% were Italian-born, whereas 37.6% were non-Italian natives. This likely reflects the enduring impact of Italy’s hepatitis B vaccination strategy, introduced in 1991 to target newborns and 12-year-olds, with continued coverage in subsequent birth cohorts and targeted pregnancy screening. HBV screening among women of childbearing age may have contributed to the disproportionately higher representation of non-Italian females (46.7%) compared to males (25.6%, P < 0.001). A similar pattern of higher female representation among individuals living with HDV infection was observed in a cohort from Romania[19]. In contrast, male predominance in HDV infection has been observed in other studies, often conducted in different regions or clinical contexts[20,21]. Several factors may account for these discrepancies, including geographic heterogeneity in the migrant population, 85.2% originating from Eastern Europe (mainly Moldova, Romania, and Albania), with smaller proportions from sub-Saharan Africa (7.7%) and Asia (2.1%) in our study. Differences in national HBV vaccination policies and their historical implementation across countries likely contribute to varying patterns of HDV exposure and infection by sex. Additionally, as specialized referral centres, the clinics participating in this study may have enrolled a higher proportion of patients with advanced liver disease, in contrast to population-based screening studies in migrant populations[20,21].

Male patients exhibited a higher prevalence of behavioral and metabolic risk factors, including alcohol use, intravenous drug use, diabetes, and HCV/HIV coinfections, which may explain their greater liver injury (as reflected by elevated GGT) and higher HCC risk[14].

While the overall prevalence of cirrhosis was high in both sexes (73.4% in males and 66.0% in females), age-stratified analysis revealed a notable and potentially significant clinical difference. Although the highest proportion of cirrhosis cases in both sexes occurred in the 56-60-year age group (33.8% in females, 34.9% in males), females, most of whom were of non-Italian origin (80.9%), were significantly more represented than males in the subgroup under 40 years of age (16.1% vs 6.5%, P < 0.05). For comparison, in the HBV mono infected cohort, analysis of enrollment (baseline) data revealed that cirrhosis was uncommon before age 55 in both sexes, consistent with the generally protective effect of younger age, particularly in females, where the increased risk typically emerged after menopause[4,7]. As reported in the literature, a similar age-related pattern to that observed in HBV monoinfection has also been described in HCV mono infection[8]. In contrast, among HDV-infected women, cirrhosis was more frequently observed at younger ages, suggesting a more aggressive disease course and a potential loss of the sex and age-related protective effect seen in HBV as well as in HCV mono infections[7].

Among patients tested for HDV RNA, viremia was detected at similar rates in males and females (68.0% vs 72.5%). However, among HDV RNA-positive individuals, a higher proportion of females were under 40 years of age compared to males (23.4% vs 13.1%). Although not statistically significant, this raises the hypothesis of sex-based differences in immunological, hormonal, or viral-host dynamics, warranting further exploration.

In our study population, cirrhosis was also common among HDV RNA-negative patients (60.0%), with a significantly higher prevalence in males than females (67.5% vs 46.8%). Several mechanisms may explain this observation. HDV viremia is dynamic, with 20%-25% of chronic HDV patients experiencing spontaneous RNA decline or clearance over time, while still displaying signs of advanced liver injury[22-25]. A single negative HDV RNA test does not exclude prior periods of active replication. This supports the need for serial, standardized HDV RNA monitoring to assess disease activity better and inform treatment decisions[14]. Moreover, HDV is recognized as a highly pathogenic virus, capable of inducing rapid fibrotic progression, even in early stages of infection, as first described by Rizzetto[10] and Rizzetto et al[26] and later confirmed by clinical studies and guidelines[14]. As such, the presence of cirrhosis in RNA-negative individuals may reflect long-standing liver damage from previous HDV-active phases, even if viral replication becomes undetectable later[14,22-25,27].

The high prevalence of advanced cirrhosis (child-Pugh B/C) in HDV-infected females underscores the importance of clinical awareness of disease severity in women, even at premenopausal ages. Although younger women bore a greater burden of cirrhosis, HCC was significantly more frequent in men with chronic HDV infection (12.9% vs 5.7%), particularly among HDV RNA-positive patients (17.9% vs 5.8%, P = 0.002). Six HCC cases also occurred in HDV RNA-negative males, and one case was reported in an HDV RNA-negative female. These patterns may reflect a higher prevalence of hepatotoxic exposures and metabolic comorbidities in men. Estrogen’s protective effects may contribute to the lower risk of HCC observed in women, even among those with cirrhosis[4].

The early onset of cirrhosis in women, particularly those under 40 and of non-Italian origin, represents a novel and clinically relevant observation. While our propensity score-adjusted analysis identified male sex as an independent predictor of cirrhosis and/or HCC, the disproportionate burden observed among younger females points to a potentially distinct disease trajectory that warrants further investigation. Although the association between male sex and cirrhosis and/or HCC reached statistical significance, the proximity of the P value to 0.05 and the lower bound of the CI near 1.0 indicate that this finding should be interpreted with caution and confirmed in future studies. Taken together, these findings highlight the complexity of sex-specific patterns in HDV-related liver disease and support the need for sex-stratified longitudinal studies to validate these differences, elucidate underlying mechanisms, and potentially inform tailored clinical strategies.

The role of HBV replication in HDV disease progression should not be underestimated[28,29]. In this patient population, over 70% of both sexes received NUC therapy, with a higher proportion of males achieving undetectable HBV DNA, though the difference was not statistically significant. These findings may reflect challenges in treatment adherence among females and underscore the need for targeted health literacy interventions, particularly for migrant and vulnerable populations.

In evaluating treatment history within this cross-sectional analysis, it is essential to note that the enrollment period preceded the approval of bulevirtide; consequently, its use was not assessed at baseline. Among the therapies available at the time of enrollment, previous exposure to IFN-based treatment was somewhat more frequent in males than in females (35.4% vs 27.7%; P = 0.084), potentially reflecting historical differences in clinical decision-making or treatment acceptance by sex. Notably, the proportion of patients meeting eligibility criteria for IFN therapy, defined by the absence of absolute or relative contraindications due to comorbidities[9], was comparable between sexes, indicating similar baseline clinical suitability for IFN-based regimens. Treatment with bulevirtide and other subsequently introduced therapies is being captured through the ongoing prospective follow-up of the cohort. This baseline evaluation thus provides a critical reference framework for investigating sex-related differences in treatment response, particularly as bulevirtide use expands within the cohort over time.

This study benefits from its large, multicenter design and robust statistical approach, including propensity score adjustment. However, its cross-sectional nature limits the ability to make causal inferences. As in other real-world cohorts, underdiagnosis of HDV remains a challenge: Approximately 25% of HBsAg-positive individuals were not screened for HDV, with no sex-based differences in testing rates, consistent with previous reports[23,30].

HDV RNA testing increased from 62%-84% between 2019 and 2024 (data not shown), paralleling the broader availability of standardized assays, notably RoboGene 2.0, which was used in 78% of the tested patients[9]. Nonetheless, the use of various assays with differing sensitivities may have introduced bias in the assessment of viremia.

In addition, the duration of HBV infection and HDV coinfection, which were not systematically captured in our cohort, may act as unmeasured confounders influencing liver disease progression. This limitation is particularly relevant when interpreting age-related cirrhosis distribution, especially among younger female patients. It may introduce bias if differences in age at HDV acquisition or HBV exposure are not accounted for.

Furthermore, to address baseline imbalances between sexes and reduce confounding, we applied IPW based on propensity scores. This method was chosen for its capacity to adjust for multiple confounders in large observational datasets involving non-randomized groups, such as sex-based comparisons. By balancing baseline characteristics across groups, IPW removes confounding in estimating exposure-outcome associations. Unlike matching or stratification, IPW retains the full sample size and provides a framework for estimating average effects[16,17]. We acknowledge that its validity depends on the absence of unmeasured confounding and that it can be sensitive to extreme weights; to address this, we applied weight stabilization and assessed covariate balance using standardized mean differences.

Finally, while this analysis focused on clinical and epidemiological patterns, unmeasured factors, such as ethnicity and socioeconomic status, as well as healthcare access, particularly among migrant women, may also influence outcomes and warrant further study. Continued prospective follow-up of this cohort will be critical to clarify the long-term impact of sex, age, viral activity, and comorbidities on HDV disease progression.

The sex-based differences observed in this study suggest distinct clinical patterns in HDV infection, with women potentially progressing to cirrhosis from young age and showing a peak at postmenopause age, often in absence of known cofactors for liver disease progression. Men more commonly had advanced liver damage, potentially linked to multiple risk factors. Contrary to trends in other chronic viral liver diseases, young female sex may not be protective in HDV. These findings call for greater clinical attention to young, migrant women, particularly those from countries without early HBV vaccination programs, who may be at risk of delayed diagnosis and suboptimal care. Recognizing sex as a potential determinant of HDV progression supports the need for sex-informed approaches in clinical management and risk assessment.

The authors would like to thank all PITER Collaborating Group Members and all participating centres, investigators, and research staff (as listed on www.progettopiter.it) who voluntarily contributed to this study. The authors also thank La Terza G (Medisoft Informatic Services) and Moghadam HE (University of Rome Tor Vergata) for their support in database maintenance and implementation. We further acknowledge Di Gregorio M, Fucili L, Lucattini S, Mirra M, Magnani F, Mattei A, Duranti R and Olivieri E for their technical and administrative assistance.

| 1. | 1 Guy J, Yee HF Jr. Health disparities in liver disease: Time to take notice and take action. Hepatology. 2009;50:309-313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Mauvais-Jarvis F, Bairey Merz N, Barnes PJ, Brinton RD, Carrero JJ, DeMeo DL, De Vries GJ, Epperson CN, Govindan R, Klein SL, Lonardo A, Maki PM, McCullough LD, Regitz-Zagrosek V, Regensteiner JG, Rubin JB, Sandberg K, Suzuki A. Sex and gender: modifiers of health, disease, and medicine. Lancet. 2020;396:565-582. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1353] [Cited by in RCA: 1418] [Article Influence: 236.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, Bray F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021;71:209-249. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75126] [Cited by in RCA: 68525] [Article Influence: 13705.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (201)] |

| 4. | Wang SH, Chen PJ, Yeh SH. Gender disparity in chronic hepatitis B: Mechanisms of sex hormones. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;30:1237-1245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 10.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Brown R, Goulder P, Matthews PC. Sexual Dimorphism in Chronic Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) Infection: Evidence to Inform Elimination Efforts. Wellcome Open Res. 2022;7:32. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ma WL, Lai HC, Yeh S, Cai X, Chang C. Androgen receptor roles in hepatocellular carcinoma, fatty liver, cirrhosis and hepatitis. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2014;21:R165-R182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 109] [Cited by in RCA: 135] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Yu MW, Chang HC, Chang SC, Liaw YF, Lin SM, Liu CJ, Lee SD, Lin CL, Chen PJ, Lin SC, Chen CJ. Role of reproductive factors in hepatocellular carcinoma: Impact on hepatitis B- and C-related risk. Hepatology. 2003;38:1393-1400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Villa E, Karampatou A, Cammà C, Di Leo A, Luongo M, Ferrari A, Petta S, Losi L, Taliani G, Trande P, Lei B, Graziosi A, Bernabucci V, Critelli R, Pazienza P, Rendina M, Antonelli A, Francavilla A. Early menopause is associated with lack of response to antiviral therapy in women with chronic hepatitis C. Gastroenterology. 2011;140:818-829. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 9. | Kondili LA, Brancaccio G, Tosti ME, Coco B, Quaranta MG, Messina V, Ciancio A, Morisco F, Cossiga V, Claar E, Rosato V, Ciarallo M, Cacciola I, Ponziani FR, Cerrito L, Coppola R, Longobardi F, Biliotti E, Rianda A, Barbaro F, Coppola N, Stanzione M, Barchiesi F, Fagiuoli S, Viganò M, Massari M, Russo FP, Ferrarese A, Laccabue D, Di Marco V, Blanc P, Marrone A, Morsica G, Federico A, Ieluzzi D, Rocco A, Foschi FG, Soria A, Maida I, Chessa L, Milella M, Rosselli Del Turco E, Madonia S, Chemello L, Gentile I, Toniutto P, Bassetti M, Surace L, Baiocchi L, Pellicelli A, De Santis A, Puoti M, Degasperi E, Niro GA, Zignego AL, Craxi A, Raimondo G, Santantonio TA, Brunetto MR, Gaeta GB; PITER Collaborating Investigators. A holistic evaluation of patients with chronic Hepatitis D virus (HDV) infection enrolled in the Italian PITER-B and delta cohort. Int J Infect Dis. 2024;146:107115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Rizzetto M. The delta agent. Hepatology. 1983;3:729-737. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 308] [Cited by in RCA: 265] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Durand F, Valla D. Assessment of the prognosis of cirrhosis: Child-Pugh versus MELD. J Hepatol. 2005;42 Suppl:S100-S107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 376] [Cited by in RCA: 443] [Article Influence: 21.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Elias S, Masad B, Nimer A. Serum Biomarkers for Evaluating Portal Hypertension. In: Patel VB, Preedy VR editors. Biomarkers in Disease: Methods, Discoveries and Applications. Germany: Springer, Dordrecht, 2016: 153-166. |

| 13. | Gotlieb N, Schwartz N, Zelber-Sagi S, Chodick G, Shalev V, Shibolet O. Longitudinal decrease in platelet counts as a surrogate marker of liver fibrosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2020;26:5849-5862. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 14. | European Association for the Study of the Liver. EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on hepatitis delta virus. J Hepatol. 2023;79:433-460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 174] [Cited by in RCA: 173] [Article Influence: 57.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL); European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD); European Association for the Study of Obesity (EASO). EASL-EASD-EASO Clinical Practice Guidelines on the management of metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD). J Hepatol. 2024;81:492-542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 949] [Article Influence: 474.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Austin PC. An Introduction to Propensity Score Methods for Reducing the Effects of Confounding in Observational Studies. Multivariate Behav Res. 2011;46:399-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6382] [Cited by in RCA: 8045] [Article Influence: 536.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Robins JM, Hernán MA, Brumback B. Marginal structural models and causal inference in epidemiology. Epidemiology. 2000;11:550-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3270] [Cited by in RCA: 3677] [Article Influence: 141.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 18. | Stockdale AJ, Kreuels B, Henrion MYR, Giorgi E, Kyomuhangi I, de Martel C, Hutin Y, Geretti AM. The global prevalence of hepatitis D virus infection: Systematic review and meta-analysis. J Hepatol. 2020;73:523-532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 478] [Article Influence: 79.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Iacob S, Gheorghe L, Onica M, Huiban L, Pop CS, Brisc C, Sirli R, Ester C, Brisc CM, Diaconu S, Rogoveanu I, Sandulescu L, Vuletici D, Trifan A. Prospective study of hepatitis B and D epidemiology and risk factors in Romania: A 10-year update. World J Hepatol. 2024;16:640-649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Zi J, Li YH, Wang XM, Xu HQ, Liu WH, Cui JY, Niu JQ, Chi XM. Hepatitis D virus dual-infection among Chinese hepatitis B patient related to hepatitis B surface antigen, hepatitis B virus DNA and age. World J Gastroenterol. 2023;29:5395-5405. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 21. | Pisaturo M, Alessio L, Di Fraia A, Macera M, Minichini C, Cordua E, Onorato L, Scotto G, Di Caprio G, Calò F, Sagnelli C, Coppola N. Hepatitis D virus infection in a large cohort of immigrants in southern Italy: a multicenter, prospective study. Infection. 2022;50:1565-1572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Palom A, Rodríguez-Tajes S, Navascués CA, García-Samaniego J, Riveiro-Barciela M, Lens S, Rodríguez M, Esteban R, Buti M. Long-term clinical outcomes in patients with chronic hepatitis delta: the role of persistent viraemia. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2020;51:158-166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 11.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Palom A, Sopena S, Riveiro-Barciela M, Carvalho-Gomes A, Madejón A, Rodriguez-Tajes S, Roade L, García-Eliz M, García-Samaniego J, Lens S, Berenguer-Hayme M, Rodríguez-Frías F, Hernandez-Évole H, Isabel Gil-García A, Barreira A, Esteban R, Buti M. One-quarter of chronic hepatitis D patients reach HDV-RNA decline or undetectability during the natural course of the disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2021;54:462-469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Kamal H, Westman G, Falconer K, Duberg AS, Weiland O, Haverinen S, Wejstål R, Carlsson T, Kampmann C, Larsson SB, Björkman P, Nystedt A, Cardell K, Svensson S, Stenmark S, Wedemeyer H, Aleman S. Long-Term Study of Hepatitis Delta Virus Infection at Secondary Care Centers: The Impact of Viremia on Liver-Related Outcomes. Hepatology. 2020;72:1177-1190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 19.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Rodríguez-Tajes S, Palom A, Giráldez-Gallego Á, Moreno A, Urquijo JJ, Rodríguez M, Alvarez-Argüelles M, Diago M, García-Eliz M, Fuentes J, Martínez-Sapiña AM, Castillo P, Casado M, Pérez-Campos E, Muñoz R, Hernández-Conde M, Morillas RM, Granados R, Miquel M, Morillas MJ, García-Retortillo M, Carrión JA, Moreno JM, Montón C, González-Santiago JM, Lorente S, Cabezas J, Mateos B, Vázquez-Rodríguez S, Díaz-Fontenla F, Pinazo JM, Delgado M, Pérez-Palacios D, Horta D, Fernández-Marcos C, López C, Calleja JL, Fernández I, García-Samaniego J, Forns X, Buti M, Lens S. Characterizing Hepatitis Delta in Spain and the gaps in its management. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2025;48:502222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Rizzetto M, Canese MG, Aricò S, Crivelli O, Trepo C, Bonino F, Verme G. Immunofluorescence detection of new antigen-antibody system (delta/anti-delta) associated to hepatitis B virus in liver and in serum of HBsAg carriers. Gut. 1977;18:997-1003. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 683] [Cited by in RCA: 654] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 27. | Romeo R, Foglieni B, Casazza G, Spreafico M, Colombo M, Prati D. High serum levels of HDV RNA are predictors of cirrhosis and liver cancer in patients with chronic hepatitis delta. PLoS One. 2014;9:e92062. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 28. | Schaper M, Rodriguez-Frias F, Jardi R, Tabernero D, Homs M, Ruiz G, Quer J, Esteban R, Buti M. Quantitative longitudinal evaluations of hepatitis delta virus RNA and hepatitis B virus DNA shows a dynamic, complex replicative profile in chronic hepatitis B and D. J Hepatol. 2010;52:658-664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 140] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Wedemeyer H. Re-emerging interest in hepatitis delta: new insights into the dynamic interplay between HBV and HDV. J Hepatol. 2010;52:627-629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Papatheodoridis G, Mimidis K, Manolakopoulos S, Triantos C, Vlachogiannakos I, Veretanos C, Deutsch M, Karatapanis S, Goulis I, Elefsiniotis I, Cholongitas E, Sevastianos V, Christodoulou D, Samonakis D, Manesis E, Kapatais A, Papadopoulos N, Ioannidou P, Germanidis G, Giannoulis G, Lakiotaki D, Kogias D, Kranidioti Η, Zisimopoulos K, Mela M, Kontos G, Fytili P, Manolaka C, Agorastou P, Pantzios SI, Papatheodoridi M, Karagiannakis D, Geladari E, Psychos N, Zachou K, Chalkidou A, Spanoudaki A, Thomopoulos K, Dalekos G. HERACLIS-HDV cohort for the factors of underdiagnosis and prevalence of hepatitis D virus infection in HBsAg-positive patients. Liver Int. 2023;43:1879-1889. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

PITER Collaborating Investigators: Aghemo Alessio, Asero Clelia, Babudieri Sergio, Baiguera Chiara, Baiocchi Leonardo, Barbaro Francesco, Barchiesi Francesco, Bassetti Matteo, Bertino Gaetano, Bertoni Costanza, Biliotti Elisa, Bonaffini Luca, Boni Carolina, Bracciamà Emanuele, Calza Leonardo, Capoluongo Nicolina, Castellaccio Alice, Cavalletto Luisa, Cenderello Giovanni, Chemello Liliana, Chessa Luchino, Chidichimo Luciana, Conti Fabio, Corsini Romina, Cosentino Clelia, Cossiga Valentina, Cotugno Rosa, D’Offizi Gianpiero, Dallio Marcello, Di Marco Vito, Falbo Elisabetta, Forni Nicola, Foschi Francesco Giuseppe, Ieluzzi Donatella, Laccabue Diletta, Loglio Alessandro, Longobardi Francesco, Madonia Salvatore, Maida Ivana, Marracci Monia, Marrone Aldo, Mastroianni Antonio, Mattioli Benedetta, Meli Rossella, Michele Milella, Nardone Gerardo, Pan Angelo, Passigato Nicola, Pellicelli Adriano, Pierotti Piera, Pinchera Biagio, Ponziani Francesca, Porcu Carmen, Risicato Alfredo, Rocco Alba, Rosato Valerio, Salsi Eleonora, Settimo Enrica, Stornaiuolo Gianfranca, Surace Lorenzo, Toniutto Pierluigi, Zanaga Paola, Zignego Anna Linda.

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/