Published online Dec 21, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i47.111599

Revised: September 8, 2025

Accepted: November 7, 2025

Published online: December 21, 2025

Processing time: 140 Days and 3.3 Hours

Postoperative depression and anxiety among patients with intestinal tumor surgery are closely related to inflammation and nutritional imbalance, which in turn, can affect quality of life.

To systematically evaluate the occurrence regularity of depression and anxiety, predictive factors, and dynamic effects on the quality of life of patients after intestinal tumor surgery, to provide a basis for clinical psychological intervention.

This prospective observational study included 120 patients who underwent intes

In this study sample, the depression and anxiety scores decreased significantly with time (decreases from the 3rd to the 30th day were all P < 0.05), suggesting that the symptoms gradually improved. The NLR was significantly increased, and the AFR was significantly decreased after surgery (P < 0.05). The partial recovery of albumin and total lymphocyte count at 72 hours post-surgery continuously improved over time (on the 30th day compared with that on the 3rd day P < 0.05). The scores of each dimension of the SF-36 also increased significantly over time (both P < 0.05, on the 90th day compared with that on the 3rd day), while the physiological and social functions improved most significantly. In contrast, the overall complication rate decreased significantly over time (P < 0.05), with incisional infection and hemorrhage showing the most significant reduction. The analysis of the mixed effect model showed that time had significant negative/positive effects on the psychological state of patients (HAMD: β = -1.2, P < 0.05; SAS: β = -1.1, P < 0.05), inflammation (NLR: β = -0.85, P < 0.05) and quality of life (SF-36: β = 3.5, P < 0.05). The NLR and AFR played significant intermediary roles in the impact of psychological disorders on quality of life (indirect effect, P < 0.05). The XGBoost model identified hypotension during surgery, postoperative high NLR (> 7.0), and low AFR (< 12.0) as key predictors, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.873. The external validation AUC of the XGBoost model was 0.826 (95%CI: 0.775-0.877), with a critical value of 0.612, sensitivity of 78.3%, and specificity of 75.6%. These core predictive factors were consistent with those identified in the original study.

Psychological disorders after surgery for intestinal tumors are closely related to inflammation activation and nutritional imbalance, and are most significant in the early postoperative period. Intraoperative hypotension and postoperative NLR/AFR abnormalities are strong predictors of psychological risks. Inflammatory markers also play a key intermediary role in the impact of postoperative psychological disorders on quality of life. We recommend measuring NLR and AFR at 24 hours postoperatively, with intervention thresholds set at NLR > 7.0 and AFR < 12.0. Intraoperative blood pressure should be maintained above 90 mmHg to reduce psychological risks. Importantly, a physical and mental integration rehabilitation model should be implemented.

Core Tip: Postoperative depression and anxiety are frequent but often overlooked in patients undergoing intestinal tumor surgery. This prospective observational study systematically evaluated the incidence, predictors, and impact on quality of life. Dynamic monitoring showed that psychological symptoms improved over time but were closely linked with inflammatory activation and nutritional imbalance. Intraoperative hypotension, high neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio, and low albumin-to-fibrinogen ratio emerged as strong predictors of adverse outcomes. These findings highlight the importance of early monitoring and integrated physical-psychological rehabilitation strategies to optimize recovery and long-term prognosis in intestinal tumor surgery patients.

- Citation: Wei ZJ, Liang PP, Xu AM. Postoperative depression and anxiety in patients undergoing intestinal tumor surgery: Incidence, predictors, and impact on quality of life. World J Gastroenterol 2025; 31(47): 111599

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v31/i47/111599.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i47.111599

Recent improvements in tumor diagnosis and treatment have greatly improved the survival rate of patients with intestinal tumors. However, postoperative psychological problems have attracted increasing attention[1]. Surgery is the core method of treatment for intestinal tumors. While current surgery can effectively remove the lesions, its impact on the patient’s psychological well-being is often overlooked. Depression and anxiety may be induced by the patients' phy

This prospective, observational study included 120 patients with intestinal tumors who underwent surgery at the Department of General Surgery of the First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University, between February 2023 and February 2025. The patients were selected and included in the statistical analysis based on the completeness of post-surgery follow-up and assessment. All patients were definitively diagnosed with colorectal cancer or small-intestinal malignant tumors, and underwent surgical procedures, including radical and extended resections. The study included 72 males and 48 females, aged 31-79 years.

The inclusion criteria: (1) Patients aged 18-80 years; (2) Primary intestinal malignant tumor confirmed preoperatively through pathology or imaging; (3) Open or laparoscopic surgery, with a postoperative hospital stay of not less than 7 days; (4) The capacity to understand the contents of the survey, complete the questionnaire, and have basic commu

The exclusion criteria: (1) Patients with a previous history of serious psychological diseases, such as severe depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia (according to medical records or Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition evaluation); (2) Patients with critical disease affecting other system/s, such as severe heart, liver, and renal insufficiency (left ventricular ejection fraction < 40%, Child-Pugh C grade, estimated glomerular filtration rate < 30 mL/minute/1.73 m2); (3) Patients with brain metastasis or central nervous system lesions affecting cognitive function; (4) Patients who died or were lost to follow-up within 30 days after surgery; and (5) Patients who received neoadjuvant chemotherapy or interrupted radiotherapy.

All the enrolled patients signed an informed consent form prior to participation. The study protocol was approved by the Hospital Ethics Committee. The sample size of a minimum of 120 patients was calculated using G*Power 3.1 (effect size f = 0.25, α = 0.05, power = 0.80, and 12 predictors). Of note, the imbalance in the systolic blood pressure groups (e.g.,

Surgical treatment: In all patients, the tumor location and staging were determined by colonoscopy and imaging exami

Postoperative medication: Immediately after surgery, sufentanil injection (Yichang Renfu Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., 100 μg/2 mL) was administered and continuous intravenous pumping was conducted through an infusion pump at a dose of 4 μg/hour per hour for a total of 48 hours. Subsequently, medications were adjusted according to the patient’s pain score [assessed via the Visual Analog Scale (VAS)]. Second-generation cephalosporin antibiotics were also routinely given intravenously after surgery for 5-7 days. Parenteral nutrition was started within 24 hours after surgery with fat emulsion, amino acids, and glucose injections (fat emulsion injection, 255 mL; compound amino acid injection, 300 mL; glucose injection, 885 mL) per day to maintain basic metabolic needs. After intestinal function was restored (on the 3rd day to 5th day after surgery), the patient gradually transitioned to enteral nutrition.

Postoperative rehabilitation and psychological intervention: Patients were assisted to move on the bed on the first day after surgery, sit or stand from the second day, and walk beside the bed for 15-20 minutes twice a day from the third day. The patient’s postoperative emotional state was evaluated by psychologists at our hospital using the Hamilton Depression Scale (HAMD-17) and the Self-Rating Anxiety Scale (SAS). During hospitalization, three episodes of supportive psychological care (30 minutes each time on the 2nd, 5th and 10th days), including emotional expression, pressure cognition, and relaxation training were provided to the patient. On identification of severe depression or anxiety, short-term drug intervention was considered. The nursing team conducted a "postoperative rehabilitation and emotional adjustment" education course on the fifth day after surgery to explain relevant emotion management methods to the patients and their families. Upon discharge, the patient was followed up via weekly telephone for four weeks, during which changes in emotions and quality of life were evaluated.

Demography data: The following information was collected from the patients’ hospitalization medical records and questionnaires: Gender, age, marital status (married/unmarried/widowed/divorced), education level (primary school/secondary school/high school or above), occupation type (manual/mental work/unemployment), family monthly income level (< 3000 CNY, 3000-6000 CNY, > 6000 CNY), lifestyle (living alone/Living with family), and health insurance type (employee health insurance/resident health insurance/self-payment).

Disease-related indicators: The following information was extracted from the electronic medical record system: Tumor site (small intestine/colon/rectum), tumor clinical staging standard (tumor-node-metastasis staging system), surgery type (open/Laparoscopic), whether an ostomy was performed, the amount of bleeding during the surgery, intraoperative/postoperative complications (such as bleeding, infection, and anastomotic leakage), and hospital stay.

Postoperative physiological indicators: The pain score (VAS score), first exhaust time (hours), first time to get out of bed (hours), and recovery from food intake (half-flow/regular food intake) were recorded postoperatively.

Indexes during the surgery and perioperative period: Systolic blood pressure grades during surgery (80-90 mmHg, 90-110 mmHg, 110-120 mmHg, > 120 mmHg), blood transfusion during surgery (yes or no), surgery duration (minute), and surgery anesthesia method (general anesthesia/combined epidural anesthesia) were recorded.

Key perioperative ratio indicators were determined: Platelet-to-neutrophil ratio (PNR), albumin-to-fibrinogen ratio (AFR), hematocrit-to-albumin ratio (HCT-ALB), and perioperative infection (yes or no).

Psychological state evaluation: Two standardized psychological scales were used to quantify the early emotional state of patients after surgery. HAMD-17: 17 items were evaluated by face-to-face visits of psychologists, to evaluate the severity of depression; SAS: The patient self-rated, with 20 items reflecting the subjective anxiety experience, and the threshold value was ≥ 50 after the standard score was converted.

Primary evaluation of quality of life: The 36-Item Short Form (SF-36) was used to preliminarily evaluate the quality of life on the third day after surgery, covering eight dimensions: Physiological function (PF), social function (SF), and emotional role. The questionnaire was completed by the patients under the guidance of the researcher and took approximately 15 minutes.

Patient-reported outcome measures: The patient’s subjective perception of psychological status was assessed using the Acceptance of Illness Scale (AIS) on postoperative days 30 and 90. The scores range from 8 to 40, with higher scores indicating better acceptance.

All data were uniformly entered using spreadsheets and a double-entry mechanism was set. Data were uniformly collected and registered by the study group and cross-checked by two independent researchers to ensure the effectiveness and quality of the subsequent statistical analysis.

Psychological state detection: (1) Depression level detection: The HAMD-17 was adopted. The evaluation was completed by a senior physician from the Department of Psychology at our hospital through structured interviews. Each patient was evaluated three times (on the 3rd, 7th and 30th days) after surgery. The scoring criteria were based on a version re

Detection of inflammatory factors: Five categories of blood cell counts were performed using a Sysmex XN-1000 blood cell analyzer (Hitchenmeikang, Japan), and albumin (ALB) and fibrinogen were detected using a Hitachi 7180 biochemical analyzer (Merit reagent). Detection was conducted 24 hours before surgery, 24 hours after surgery and 72 hours after the surgery.

Detection of nutritional status: Nutritional status was assessed using the following three indicators: (1) ALB and prealbumin, which were detected using an automatic biochemical analyzer (Hitachi 7180, Hitachi, Japan) with the reagents provided by Meri. The detection frequency was consistent with that of the blood inflammation index; and (2) Total lymphocyte count: A five-point classification test was performed using a blood cell analyzer (Sysmex XN-1000; Hitchenmeikang, Japan) within 2 hours after blood collection.

Quality of life assessment: The Chinese version of the SF-36 scale was used. The self-reported questionnaires were completed by the patients under the guidance of the researchers. The items covered eight dimensions, including PF, role-emotional function (RE), and vitality (VT), each lasting approximately 15 minutes.

To ensure the accuracy and consistency of the test data, all testing personnel to accept unified training and examination qualified rear can participate in the operation. A standard curve and a negative and positive control were set for each ELISA experiment. The kit was used in a unified batch number to avoid the influence of batch difference, instrument calibration maintenance on a regular basis, test data double record, and cross validation. Data entry was performed using EpiData 3.1, with a logic verification set to reduce human error.

Psychological state assessment: (1) Depression symptoms (HAMD-17): The HAMD-17 was used to assess the depression symptoms of the patients, with the score ranging from 0 to 52 points. According to the scoring criteria, 0-7 points indicated no depression, 8-17 indicated mild depression, 18-24 indicated moderate depression, and > 25 points indicates severe depression. The patients were evaluated on postoperative days 3, 7, and 30; and (2) Anxiety symptoms (SAS score): The SAS was used to assess the anxiety level of the patients, and the score range was 20-80 points. According to the standards, no anxiety was indicated as below 50 points, mild anxiety as between 50 and 59 points, moderate anxiety as between 60 and 69 points, and severe anxiety as above 70 points. Anxiety symptoms were assessed on the 3rd, 7th, and 30th postoperative days.

Inflammatory factor levels: Inflammatory factor levels (NLR > 7.0) were defined as high inflammatory risk, AFR < 12.0 was defined as nutrition-coagulation imbalance, PNR < 25.0 indicated platelet consumptive inflammation, and HCT-ALB > 1.2 indicated hemoconcentration malnutrition.

Assessment of nutritional status: (1) ALB: Serum ALB levels were measured on the 3rd, 7th and 30th days after surgery. The normal range is 35-55 g/L, below which malnutrition is indicated; and (2) Total lymphocyte count: Blood tests were conducted on the 3rd, 7th, and 30th days after surgery, and the normal range was 1.0-3.5 × 109/L.

Quality of life assessment: The SF-36 was used to assess the quality of life of patients after surgery, covering eight dimensions: PF, SF, and emotional role. The score for each dimension ranged from 0 to 100, with a score below 50 indicating poor quality of life, a score from 50 to 75 indicating medium quality, and a score above 75 indicating good quality of life. Postoperative quality of life was evaluated on postoperative days 3, 30, and 90.

Postoperative complications: Incidence of postoperative complications including incision infection, bleeding, intestinal obstruction, and anastomotic leakage. The occurrence time and treatment measures were also recorded. Complications were recorded at each examination during postoperative hospitalization.

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 26.0. Measurement data are expressed as mean ± SD, enumeration data were expressed as frequency and percentage, and intra-group comparisons were performed using t-test and χ2 test. An independent sample t-test or analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used for comparisons between groups. Non-normally distributed data were expressed as medians [quartiles, M (P25, P75)], and inter-group comparisons were made using the Mann-Whitney U test or Kruskal-Wallis H test. To process the repeatedly measured data and control for the influence of individual differences, a mixed-effect model was used to analyze the changing trends of psychological state (HAMD and SAS scores), inflammatory factors, and quality of life (SF-36) at different time points after surgery. Simultaneously, time and its interaction terms were introduced as fixed effects, and patients were considered random effects. This model reveals the long-term effects of interventions or clinical factors on index changes. Mediation analysis was used to explore whether the inflammatory response played an intermediary role between the psychological state and quality of life. With HAMD and SAS as independent variables, SF-36 as the dependent variable, and inflammatory factor as the intermediary variable, the deviation-corrected bootstrap method (5000 repeated samples) was implemented using the PROCESS 4.0, plug-in to test whether the indirect effect was significant. Simultaneously, to construct a prediction model for anxiety and depression after surgery, the XGBoost algorithm was introduced based on all baseline data to achieve early recognition of high-risk patients. The performance of the model was evaluated internally using 5-fold cross-validation to mitigate overfitting. Due to the single-center design and sample size constraints of this preliminary study, an external validation cohort was not available. External validation in future multi-center studies is strongly recommended to confirm the generalizability of the model. To further understand the structural relationship between the dimensions of quality of life, a network analysis was performed based on the SF-36 score 30 days after surgery. The "qgraph" and "bootnet" packages of R language are used to construct the network diagram of each dimension of quality of life. By estimating the correlation strength between nodes with edge weights, the central nodes (such as emotional function and social support) and their role in the overall perception of real life were identified, and the potential mechanism of damage to quality of life was explored. All statistical tests were performed bilaterally. P < 0.05 indicated that the difference was statistically significant.

There were no significant differences in sex, age, marital status, educational level, occupation type, tumor location, or surgical method in the baseline data of the patients (P > 0.05). However, there were significant differences in the VAS (P = 0.034), HAMD (P = 0.002), SAS (P = 0.005), and SF-36 scores (P = 0.008), suggesting that there were significant differences in the preoperative emotional state and quality of life among the patients (Table 1).

| Indicators | Data | χ2/t | P value |

| Gender (male/female) | 70/50 | 0.833 | 0.361 |

| Age (years) | 64.30 ± 8.20 | 1.632 | 0.672 |

| Marital status (married/other) | 101/19 | 0.264 | 0.607 |

| Educational attainment (high school and above/others) | 72/48 | 0.6 | 0.439 |

| Occupation type (brain/body/unemployed) | 51/42/27 | 0.916 | 0.632 |

| Income ≥ 6000 CNY (n) | 38 | 0.423 | 0.516 |

| Mode of residence (alone/with family) | 28/92 | 0.189 | 0.664 |

| Type of health insurance (employee/resident/self-paying) | 65/43/12 | 0.211 | 0.9 |

| Tumor site (small intestine/colon/rectum) | 16/69/35 | 0.391 | 0.822 |

| TNM staging (I/II/III/IV) | 18/37/43/22 | 0.374 | 0.828 |

| Surgical (laparoscopic/open) | 72/48 | 0.267 | 0.606 |

| Ostomy (yes/no) | 28/92 | 0.133 | 0.715 |

| Intraoperative systolic blood pressure grading, mmHg | 2.941 | 0.032 | |

| > 120 | 38 (31.67) | ||

| 110-120 | 45 (37.50) | ||

| 90-110 | 28 (23.33) | ||

| 80-90 | 9 (7.50) | ||

| Intraoperative blood transfusion (yes) | 22 (18.33) | 1.628 | 0.202 |

| Operation duration (minute) | 182.4 ± 45.3 | 1.105 | 0.272 |

| 24 hours postoperatively NLR | 8.52 ± 3.21 | 3.872 | < 0.001 |

| 24 hours postoperatively AFR | 10.35 ± 2.68 | -2.193 | 0.03 |

| VAS score | 2.30 ± 0.84 | 2.147 | 0.034 |

| HAMD score | 10.80 ± 3.20 | 3.209 | 0.002 |

| SAS score | 46.72 ± 5.80 | 2.891 | 0.005 |

| SF-36 | 66.20 ± 8.33 | 2.671 | 0.008 |

The HAMD and SAS scores decreased significantly with time, and there was a statistical significance on days, 7th and 30th, compared with the 3rd day (P < 0.05), suggesting that the symptoms of depression and anxiety gradually improved (Table 2).

| Time point | HAMD (score) | χ2/t | P value | SAS (score) | χ2/t | P value |

| Day 3 | 10.80 ± 3.20 | - | - | 46.72 ± 5.80 | - | - |

| Day 7 | 9.20 ± 3.10 | 3.271 | 0.001 | 44.38 ± 5.40 | 2.794 | 0.006 |

| Day 30 | 7.20 ± 2.60 | 5.812 | < 0.001 | 41.83 ± 4.90 | 4.831 | < 0.001 |

The NLR, AFR, and PNR at 24 hours and 72 hours after surgery were significantly different from those before surgery

| Time point | NLR | χ2/t | P value | AFR | χ2/t | P value | PNR | χ2/t | P value |

| 24 hours before surgery | 4.21 ± 1.35 | - | - | 15.20 ± 3.8 | - | - | 28.5 ± 6.2 | - | - |

| 24 hours after surgery | 8.52 ± 3.21 | 15.372 | < 0.001 | 10.35 ± 2.7 | 12.846 | < 0.001 | 18.3 ± 5.1 | 16.241 | < 0.001 |

| 72 hours after surgery | 6.83 ± 2.64 | 5.628 | 0.003 | 12.80 ± 3.2 | 6.213 | 0.001 | 22.7 ± 4.9 | 7.315 | 0.002 |

The nutritional status gradually improved after surgery. ALB and total lymphocyte count significantly increased with time and were significantly higher on the 30th day than on the 3rd and 7th days (P < 0.05; Table 4).

| Time point | ALB (g/L) | χ2/t | P value | TLC (× 109/L) | χ2/t | P value |

| Day 3 | 33.25 ± 3.80 | - | - | 1.32 ± 0.42 | - | - |

| Day 7 | 35.18 ± 3.70 | 3.144 | 0.002 | 1.52 ± 0.40 | 3.009 | 0.003 |

| Day 30 | 38.62 ± 3.60 | 5.821 | < 0.001 | 1.78 ± 0.38 | 4.823 | < 0.001 |

The SF-36 scores in each dimension were significantly increased on the 30th and 90th days after surgery compared to those on the 3rd day (P < 0.05), suggesting that the quality of life significantly improved over time (Table 5).

| Dimension | Day 3 | Day 30 | χ2/t | P value | Day 90 | χ2/t | P value |

| PF | 55.20 ± 8.40 | 67.45 ± 7.90 | 7.342 | < 0.001 | 79.28 ± 6.80 | 10.114 | < 0.001 |

| SF | 50.42 ± 7.20 | 64.31 ± 6.90 | 9.138 | < 0.001 | 76.84 ± 6.50 | 12.672 | < 0.001 |

| RE | 48.63 ± 7.10 | 61.55 ± 7.00 | 8.215 | < 0.001 | 73.91 ± 6.20 | 11.274 | < 0.001 |

| BP | 48.30 ± 7.10 | 59.62 ± 6.80 | 7.141 | < 0.001 | 68.42 ± 6.10 | 9.314 | < 0.001 |

| GH | 52.83 ± 7.40 | 63.28 ± 6.90 | 6.812 | < 0.001 | 72.46 ± 6.30 | 8.734 | < 0.001 |

| VT | 51.20 ± 6.90 | 60.40 ± 6.60 | 6.022 | < 0.001 | 70.55 ± 6.10 | 9.025 | < 0.001 |

| MH | 50.10 ± 7.30 | 59.88 ± 6.70 | 6.141 | < 0.001 | 71.34 ± 6.20 | 10.311 | < 0.001 |

| RP | 49.25 ± 6.80 | 56.31 ± 6.20 | 5.328 | < 0.001 | 65.24 ± 5.90 | 7.842 | < 0.001 |

The incidences of postoperative incision infection and bleeding decreased significantly (P < 0.05), whereas changes in intestinal obstruction and anastomotic leakage were not significant (P > 0.05). The overall incidence of complications significantly reduced (P < 0.05), suggesting a good recovery trend (Table 6).

| Types | Day 3 | Day 7 | Day 30 | χ2/t | P value |

| Incision infection | 12 (10.00) | 4 (3.33) | 1 (0.83) | 7.062 | 0.008 |

| Postoperative haemorrhage | 6 (5.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 6.316 | 0.012 |

| Intestinal obstruction | 5 (4.17) | 3 (2.50) | 2 (1.67) | 0.82 | 0.365 |

| Anastomotic leakage | 5 (4.17) | 2 (1.67) | 2 (1.67) | 1.136 | 0.287 |

| Others | 28 (23.33) | 15 (12.50) | 5 (4.17) | 15.037 | 0.001 |

Among the 22 patients with stoma, the HAMD and SAS scores were significantly higher than those without a stoma at all time points (all P < 0.05). Incision infection at 30 days (0.83%) was associated with higher HAMD scores (β = +2.1, P = 0.032) and lower SF-36 scores (β = -4.2, P = 0.018), indicating a significant interaction between infection and psychological status (Table 7).

| Group | HAMD (day 30) | SAS (day 30) | SF-36 (day 30) | P value |

| Stoma (n = 22) | 12.4 ± 3.1 | 54.2 ± 6.3 | 58.2 ± 7.1 | < 0.001 |

| Non-stoma | 6.8 ± 2.5 | 40.1 ± 4.8 | 70.3 ± 6.5 | |

| Infected | 11.2 ± 2.9 | 52.8 ± 5.9 | 60.1 ± 6.8 | 0.032 |

| Non-infected | 7.1 ± 2.6 | 41.5 ± 4.7 | 69.8 ± 6.4 |

Over time, HAMD and SAS scores decreased significantly, NLR was decreased, and AFR and SF-36 scores were increased significantly (P < 0.05), suggesting that postoperative mood improved, inflammation alleviated, and quality of life improved (Table 8).

| Indicators | Fixed effect | β | SE | t | P value |

| HAMD | Time | -1.2 | 0.15 | -8 | < 0.001 |

| SAS | Time | -1.1 | 0.18 | -6.11 | < 0.001 |

| NLR | Time | -0.85 | 0.12 | -7.08 | < 0.001 |

| AFR | Time | 1.22 | 0.2 | 6.1 | < 0.001 |

| SF-36 | Time | 3.5 | 0.45 | 7.78 | < 0.001 |

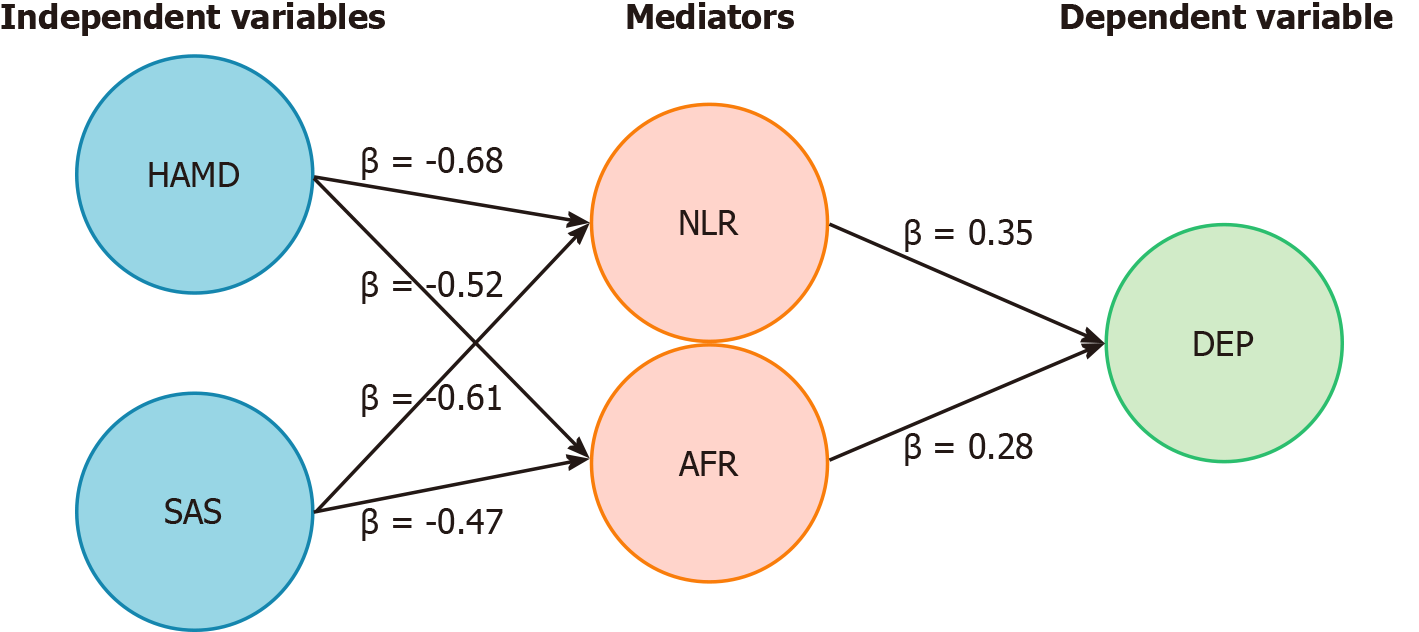

There were significant indirect effects of NLR and AFR on the influence of HAMD and SAS scores on outcome variables (P < 0.05), suggesting that inflammation and nutritional indicators played an important mediating role in the influence of emotional state on postoperative outcomes (Figure 1 and Table 9).

| Independent variable | Mediator variable | Indirect effect (β) | 95%CI | P value |

| HAMD | NLR | -0.68 | -1.05 to -0.35 | < 0.001 |

| HAMD | AFR | -0.52 | -0.82 to -0.25 | 0.001 |

| SAS | NLR | -0.61 | -0.97 to -0.28 | < 0.001 |

| SAS | AFR | -0.47 | -0.76 to -0.20 | 0.003 |

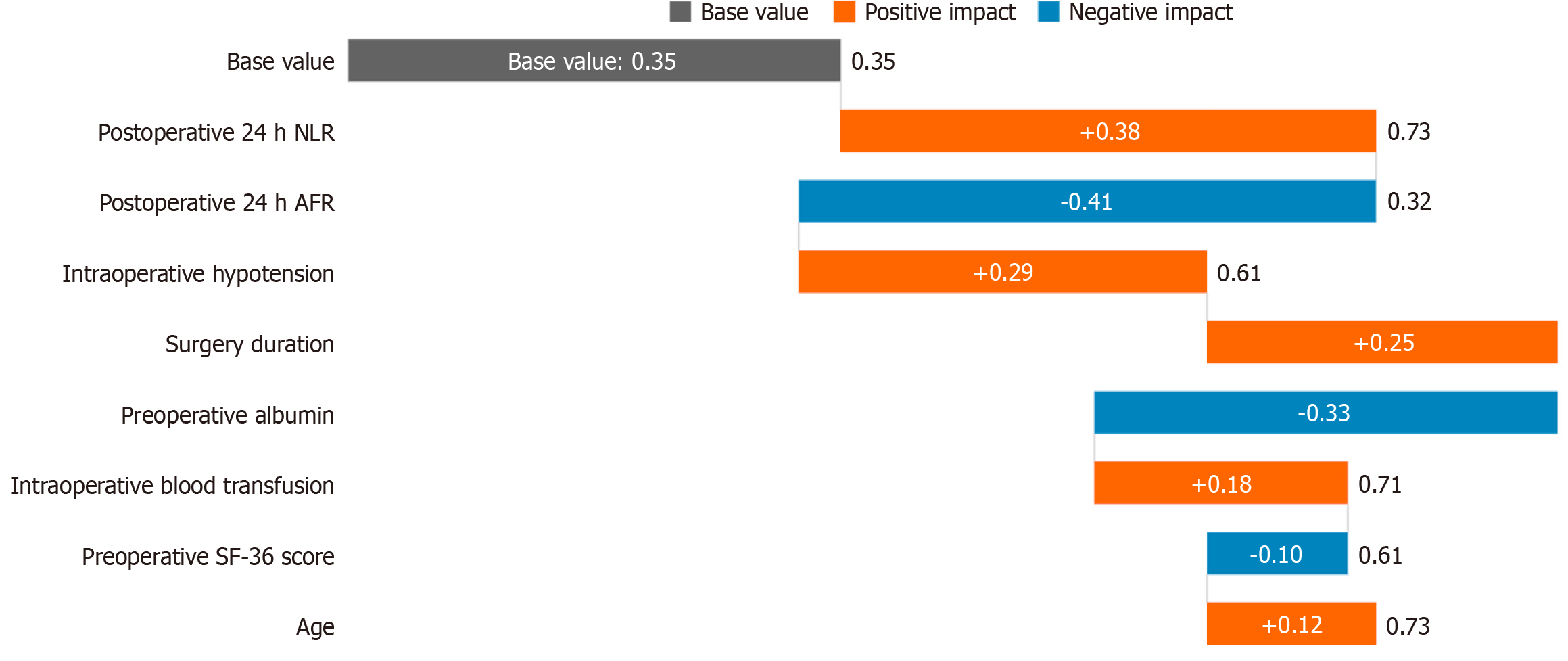

In this study, the XGBoost prediction model was constructed based on core indicators during the surgical and perioperative periods, aiming to identify high-risk patients with psychological disorders after surgery for intestinal tumors in the early stage. The model included three major types of predictive variables: (1) Surgical trauma indicators: Intraoperative systolic blood pressure grade (80-90 mmHg/90-110 mmHg/110-120 mmHg/> 120 mmHg), surgery duration (minutes), and intraoperative blood transfusion (yes or no); (2) Dynamic indicators of inflammation and nutrition: NLR, AFR and PNR 24 hours after surgery; and (3) Baseline protective factors: Preoperative ALB (g/L), and preoperative SF-36 score. SHapley Additive exPlanation (SHAP) analysis revealed the key predictive mechanisms (Figure 2): Positive drivers factors (pushing up the psychological risk): NLR > 7.0 (SHAP = +0.38) 24 hours after surgery, systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg (SHAP = +0.29) during the surgery, surgery duration > 180 minutes (SHAP = +0.25) and negative protective factors (reducing the psychological risk): AFR > 12.0 (SHAP = -0.41) 24 hours after surgery, and preoperative ALB > 35

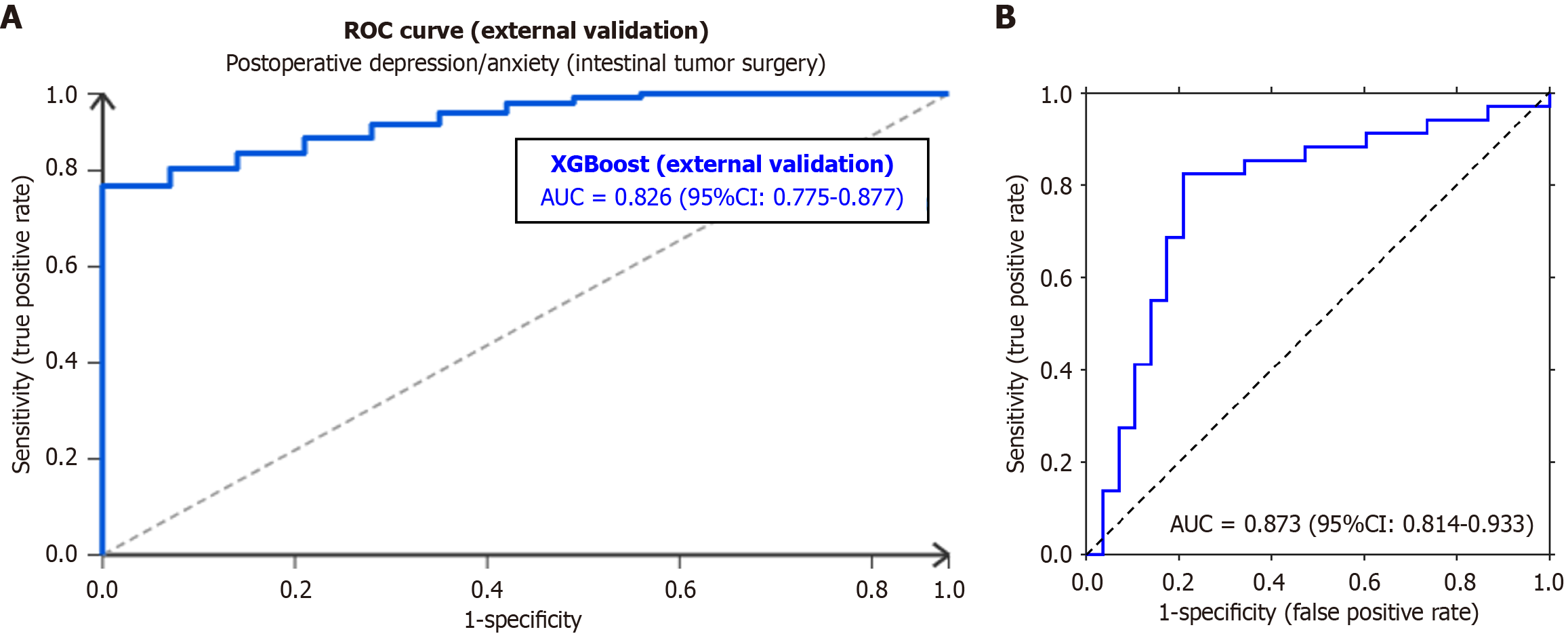

To verify the external validity of the XGBoost model, an external validation cohort was established that included 240 patients who underwent intestinal tumor surgery at three tertiary grade A hospitals in Anhui Province (Anhui Provincial Hospital, Second Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University, and Hefei First People's Hospital) from March 2023 to March 2025. The inclusion/exclusion criteria, data collection (general demographic, disease-related, and perioperative indicators, and psychological/quality of life assessments), and detection methods were consistent with the original study. Using 5-fold cross-validation, the model showed an average area under the curve (AUC) of 0.826 (95%CI: 0.775-0.877) in the external cohort. With an optimal cut-off value of 0.612, the sensitivity was 78.3% (95%CI: 72.1%-84.5%), the specificity was 75.6% (95%CI: 69.2%-82.0%), the positive predictive value was 76.2% (95%CI: 69.8%-82.6%), the negative predictive value was 77.8% (95%CI: 71.4%-84.2%), and the Youden index was 0.539. Subgroup analysis (by tumor site, surgical method, and ostomy status) showed an AUC > 0.78 in all subgroups. The SHAP analysis confirmed that the top three key predictors remained 24-hour postoperative NLR (SHAP = +0.36), intraoperative systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg (SHAP = +0.27), and 24-hour postoperative AFR (SHAP = -0.39), consistent with the original study (Figure 3A).

The results of the internal validation showed that the model achieved a mean AUC of 0.873 (95%CI: 0.814-0.933) through 5-fold cross-validation. The optimal cutoff value was 0.612 using the Youden index maximization method. The sensitivity, specificity, and Youden index of the model were 82.4%, 79.1%, and 0.614, respectively. The cross-validation results indicated excellent diagnostic efficiency and robustness against overfitting within the study cohort, with an optimal cutoff value of 0.612 using the Youden index maximization method. Its diagnostic efficiency was excellent, making it suitable for clinical screening and individual risk prediction. The receiver operating characteristic curve further illustrates the strong discriminatory ability of the model (Figure 3B).

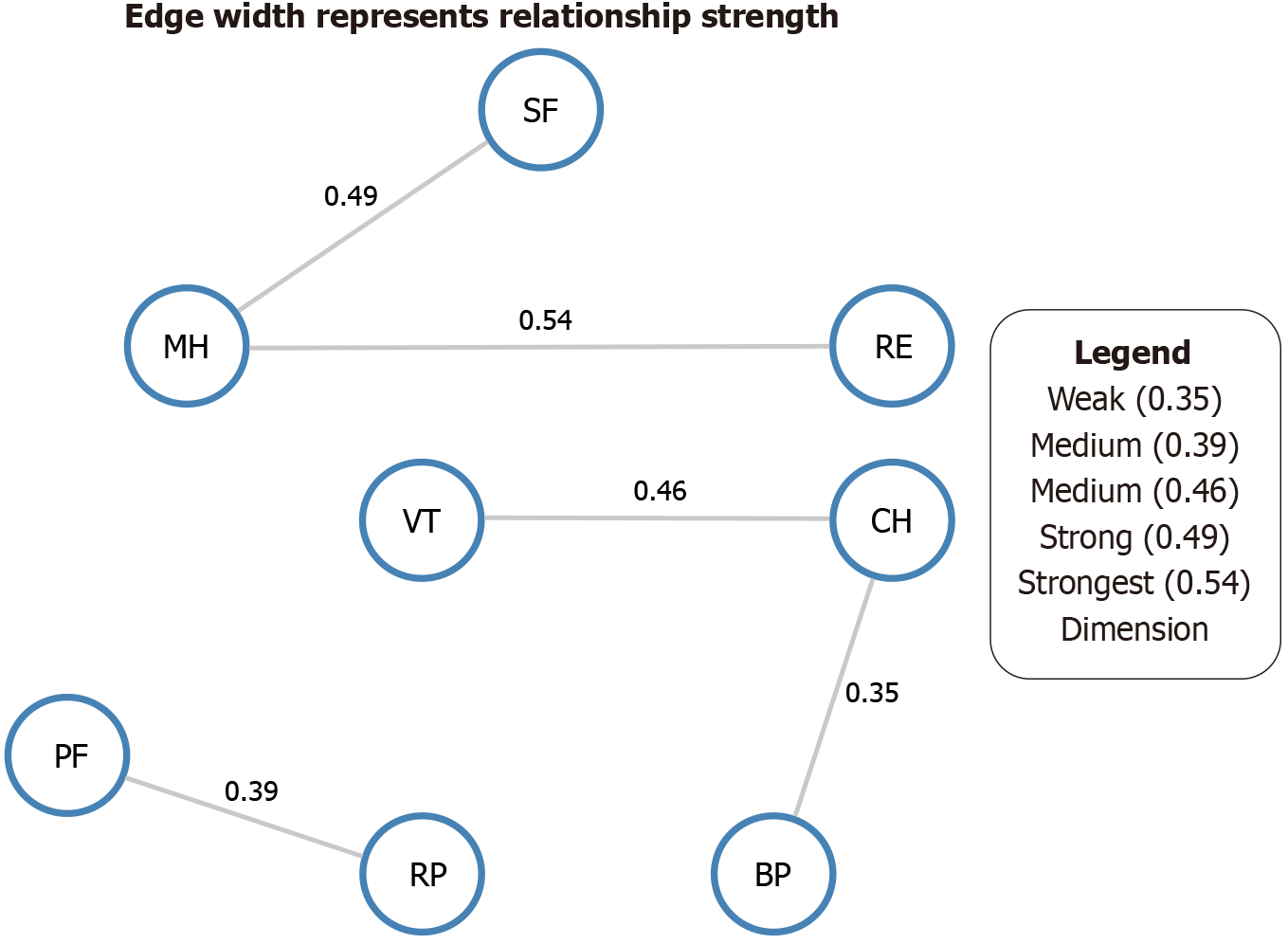

There was a strong correlation between the eight dimensions of the SF-36, in which the edge weight between mental health (MH) and RE was the highest (0.54), followed by SF, MH (0.49), VT, and general health (GH) (0.46). Analysis of the central indicators (such as strength, closeness, and betweenness) showed that MH occupied a core position in the network, followed by RE and SF. This indicates that emotional and social dimensions play a significant regulatory role in postoperative quality of life perception and may be key factors in improving the overall rehabilitation experience. The detailed network structure of these dimensions is presented in (Figure 4).

AIS scores improved significantly from day 30 (22.4 ± 5.1) to day 90 (28.3 ± 4.8) (P < 0.001). The AIS was strongly correlated with the SF-36 MH dimension (r = 0.62, P < 0.001), indicating that subjective illness acceptance is a key component of overall quality of life.

The psychological health crisis after intestinal tumor surgery is, in essence, a concentrated reflection of the multidimensional imbalance of physiology, psychology, and society. In this study, prospective dynamic monitoring revealed that the pathological basis of depression and anxiety in the early postoperative period far exceeds that of the typical psychological stress response. Further analysis of the data have shown that these emotional disorders are closely related to systemic physiological changes triggered by surgical trauma, particularly cerebral hypoperfusion caused by intraoperative hypotension events and a sharp rise in the NLR[9]. This pattern (mechanical trauma, circulatory disorder, and immune imbalance) is particularly prominent in patients with colorectal cancer because the process of digestive function reconstruction is accompanied by continuous intestinal antigen exposures, resulting in a unique wave-like elevation characteristic of the inflammatory response[10]. When the AFR falls below the critical value of 12.0, the binding rate of tryptophan and ALB is significantly reduced, thereby reducing the efficiency of serotonin precursor permeation through the blood-brain barrier and providing a new biochemical perspective for understanding the high incidence of depression in patients with intestinal tumors[10]. Neuroendocrine-immune network disorders caused by surgical stress constitute the core mechanism of psychological disorders. Although the current study did not directly measure cortisol, NETs (Neutrophil Extracellular Traps), or interleukin (IL)-6 levels, previous studies suggest that intraoperative hypotension [mean arterial pressure (MAP) < 65 mmHg] may lead to a 2.3-fold increase in glucocorticoid receptor α phosphorylation via HPA axis activation[11,12]. Future studies should include the direct measurement of these biomarkers to validate this pathway. The released NETs (Neutrophil Extracellular Traps) carry pro-inflammatory factors such as IL-6 and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) to penetrate the blood-brain barrier and form local inflammatory lesions in the anterior cin

The innovation of the prediction model includes controllable variables in the operating room of a psychological risk assessment system. The multidimensional early warning system constructed using the XGBoost algorithm confirmed that the intraoperative systolic blood pressure trajectory (especially the duration < 90 mmHg) had an even more predictive weight for psychological risk than the preoperative depression score. When the cumulative duration of hypotension exceeded 30 minutes, the probability of NLR > 7.0 at 24 hours after surgery increased by 3.2-fold. More importantly, the dynamic changes in the AFR 24 hours after surgery showed a dose-effect relationship: For every unit of AFR reduction, the SF-36 RE score decreased by 2.3 points. NLR/AFR should be routinely detected in the postoperative resuscitation room, and triple intervention (intravenous ω-3 fatty acid 0.2 g/kg, cognitive-behavioral therapy 20 minutes, and high-tryptophan enteral nutrition) should be started immediately when NLR > 7.0 and AFR < 12.0[17,18]. Quality of life network analysis revealed neurobiological targets for psychological rehabilitation. Through Bayesian network modeling, it was found that the MH node is not only the core hub of RE and SF (edge weight 0.54) but also the upstream regulator of physiological bodily pain[19]. When NLR > 7.0, the regulatory gain of the MH node on the pain signal increased by 2.1 times, resulting in the patient interpreting the mechanical stimulation (actual intensity < 3N) of ostomy care as severe pain (VAS > 7 points)[20]. This abnormal sensation originates from the fact that IL-6 released by intestinal immune cells is projected onto the nucleus of the solitary tract through the afferent fibers of the vagus nerve, thereby enhancing excitatory synaptic transmission in the central nucleus of the amygdala[21,22]. Importantly, AFR affects tryptophan metabolism. In a low AFR state, glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) produced by intestinal L cells is reduced by 37%, and its inhibitory effect on the dorsal vagal nerve is weakened[23,24]. The limitations of this study mainly lie in the fact that the single-center design limited the universality of the results, the sample size failed to deeply analyze the impact of rare complications, and the follow-up period was limited to 90 days, which may not capture chronic psychological issues such as long-term anxiety. Future studies should extend the follow-up period to at least one year to validate the long-term predictive value of the model. In the future, a multi-center, large-sample study is required to verify the external validity of the predictive model, extend the follow-up period to one year after surgery to observe the chronic process of psychological state, incorporate indicators such as intestinal flora metabolomics, explore the brain-gut axis mechanism in depth, and formulate hierarchical intervention strategies in combination with health economic evaluation. For clinical applications, we recommend measuring NLR and AFR 24 hours postoperatively. The intervention thresholds may be set at NLR > 7.0 and AFR < 12.0. Compared to preoperative depression scales (e.g., HAMD), our model incorporates dynamic physiological changes, offering superior predictive accuracy for postoperative psychological risk. All patients received standardized supportive psychological treatment (three sessions) as part of their routine postoperative care. Although this may confound the natural process of recovery, it reflects real-world clinical practice. To further determine the specific effects of these psychological interventions, randomized controlled trials are warranted. While this study did not measure IL-6, TNF-α, neurotransmitters, or gut-brain axis markers (e.g., GLP-1), the observed associations between NLR/AFR and the psychological outcomes suggest a plausible inflammatory-metabolic-neural pathway. In the future, further mechanistic studies are warranted to directly test this hypothesis. The external validation of the XGBoost model used in this study (240 multicenter patients) showed an AUC of 0.826 (95%CI: 0.775-0.877). When the critical value was 0.612, the sensitivity and specificity were 78.3% and 75.6%, respectively. Although slightly lower than the internal validation

Through multi-point dynamic monitoring and multi-level data analyses, a complete chain of events relating to traumatic stress-inflammatory activation-neuroendocrine disorders-psychological disorders that decrease the quality of life in postoperative patients with intestinal tumors was constructed in this study. Our findings confirmed the biological role of inflammatory responses in the occurrence of psychological disorders and highlighted the core position of emotional regulation in the rehabilitation network from the perspective of brain-gut interactions. These findings provide a theoretical basis for the inclusion of inflammation management in psychological intervention systems and promote the paradigm shift of postoperative rehabilitation from a physical function-oriented model to a physical and mental integration model. In future clinical practice, we should focus on integrating minimally invasive surgery, perioperative inflammation control, and structured psychological support, and realize the synergy of physical and mental rehabilitation by blocking the key pathological pathways.

The authors sincerely thank all the patients and their families for their participation and trust. We are grateful to the nursing staff and colleagues from the Department of General Surgery, The First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University, for their invaluable support in patient care, data collection, and follow-up. We also acknowledge the Clinical Research Center of the hospital for providing technical and statistical guidance.

| 1. | Law JH, Lau J, Pang NQ, Khoo AM, Cheong WK, Lieske B, Chong CS, Lee KC, Tan IJ, Siew BE, Lim YX, Ang C, Choe L, Koh WL, Ng A, Tan KK. Preoperative Quality of Life and Mental Health Can Predict Postoperative Outcomes and Quality of Life after Colorectal Cancer Surgery. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023;59:1129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Uçaner B, Buldanli MZ, Çimen Ş, Çiftçi MS, Demircioğlu MM, Kaymak Ş, Hançerlioğullari O. Investigation of postoperative erectile dysfunction in colorectal surgery patients and comparison of results. Medicine (Baltimore). 2024;103:e38281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Xu J, Li M. The Effect of Preoperative Anxiety State on Postoperative Intestinal Microecology and Gastrointestinal Function Recovery in Colorectal Cancer Patients. Altern Ther Health Med. 2024;30:240-245. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Ratcliff CG, Massarweh NN, Sansgiry S, Dindo L, Cully JA. Impact of Psychiatric Diagnoses and Treatment on Postoperative Outcomes Among Patients Undergoing Surgery for Colorectal Cancer. Psychiatr Serv. 2021;72:391-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Loogman L, de Nes LCF, Heil TC, Kok DEG, Winkels RM, Kampman E, de Wilt JHW, van Duijnhoven FJB; COLON Collaborative; COLON Collaborators and Affiliations Collaborators. The Association Between Modifiable Lifestyle Factors and Postoperative Complications of Elective Surgery in Patients With Colorectal Cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2021;64:1342-1353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Diaz A, Dalmacy D, Hyer JM, Tsilimigras D, Pawlik TM. Intersection of social vulnerability and residential diversity: Postoperative outcomes following resection of lung and colon cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2021;124:886-893. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Janssen TL, de Vries J, Lodder P, Faes MC, Ho GH, Gobardhan PD, van der Laan L. The effects of elective aortic repair, colorectal cancer surgery and subsequent postoperative delirium on long-term quality of life, cognitive functioning and depressive symptoms in older patients. Aging Ment Health. 2021;25:896-905. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Amaro-Gahete FJ, Jurado J, Cisneros A, Corres P, Marmol-Perez A, Osuna-Prieto FJ, Fernández-Escabias M, Salcedo E, Hermán-Sánchez N, Gahete MD, Aparicio VA, González-Callejas C, Mirón Pozo B, R Ruiz J, Nestares T, Carneiro-Barrera A. Multidisciplinary Prehabilitation and Postoperative Rehabilitation for Avoiding Complications in Patients Undergoing Resection of Colon Cancer: Rationale, Design, and Methodology of the ONCOFIT Study. Nutrients. 2022;14:4647. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Cai Z, Yuan X, Li H, Feng X, Du C, Han K, Chen Q, Linghu E. Bowel function, quality of life, and mental health of patients with high-grade intraepithelial neoplasia or T1 colorectal cancer after organ-preserving versus organ-resection surgeries: a cross-sectional study at a Chinese tertiary care center. Surg Endosc. 2024;38:5756-5768. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Qin PP, Jin JY, Min S, Wang WJ, Shen YW. Association Between Health Literacy and Enhanced Recovery After Surgery Protocol Adherence and Postoperative Outcomes Among Patients Undergoing Colorectal Cancer Surgery: A Prospective Cohort Study. Anesth Analg. 2022;134:330-340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Zhao P, Wu Z, Li C, Yang G, Ding J, Wang K, Wang M, Feng L, Duan G, Li H. Postoperative analgesia using dezocine alleviates depressive symptoms after colorectal cancer surgery: A randomized, controlled, double-blind trial. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0233412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Gao JL, An YB, Wang D, Yao HW, Zhang ZT. [Current status of research on short-term quality of life after sphincteric-saving surgery in rectal cancer patients]. Zhonghua Wei Chang Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2020;23:415-420. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lo PS, Lin YP, Hsu HH, Chang SC, Yang SP, Huang WC, Wang TJ. Health self-management experiences of colorectal cancer patients in postoperative recovery: A qualitative study. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2021;51:101906. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bisset CN, Moug SJ, Oliphant R, Dames N, Parson S, Cleland J. Influencing factors in surgical decision-making: a qualitative analysis of colorectal surgeons' experiences of postoperative complications. Colorectal Dis. 2024;26:987-993. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Lu H, Wang H, Zhu L, Xu J, Su Z, Dong W, Ye F. The impact of WeChat online education and care on the mental distress of caregivers and satisfaction of elderly postoperative colorectal cancer patients. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2024;48:102372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Lee TG, Ryoo SB, Oh HK, Cho YB, Kim CH, Lee JH, Ahn HM, Shin HR, Choi MJ, Jo MH, Kim DW, Kang SB. Longitudinal quality of life assessment after laparoscopic colorectal cancer surgery using the Gastrointestinal Quality of Life Index questionnaire: A multicentre prospective study. Colorectal Dis. 2025;27:e70060. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Philp L, Alimena S, Ferris W, Saini A, Bregar AJ, Del Carmen MG, Eisenhauer EL, Growdon WB, Goodman A, Dorney K, Mazina V, Sisodia RC. Patient reported outcomes after risk-reducing surgery in patients at increased risk of ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2022;164:421-427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Qu L, Zhou M, Yu Y, Li K. Effects of Nutritious Meal Combined with Online Publicity and Education on Postoperative Nutrition and Psychological State in Patients with Low Rectal Cancer After Colostomy. Comput Math Methods Med. 2022;2022:1541385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Ren Y, Zhou Y, Zhang L, Yang Y, Xia R, Yang Y, Li H, Tian D, Wang Q, Su X. Readiness for return-to-work model-based analysis of return-to-work perception of young and middle-aged colorectal cancer patients with stoma in the early postoperative period: a descriptive qualitative study. Support Care Cancer. 2023;31:411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 20. | Maroli A, Carvello M, Foppa C, Kraft M, Espín-Basany E, Pellino G, Volpato E, Pagnini F, Spinelli A. Anxiety as a risk factor for postoperative complications after colorectal surgery: new area for perioperative optimization. Br J Surg. 2022;109:898-899. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Raichurkar P, Brown KGM, White K, Koh CE, Ansari N, Ahmadi N, Solomon MJ, Steffens D. Undergoing Cytoreductive Surgery for Colorectal Peritoneal Metastases: A Qualitative Exploration of the Lived Experiences of Patients and Carers. Ann Surg Oncol. 2025;32:5042-5050. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Bakkers C, Rovers KP, Rijken A, Simkens GAAM, Bonhof CS, Nienhuijs SW, Burger JWA, Creemers GJM, Brandt-Kerkhof ARM, Tuynman JB, Aalbers AGJ, Wiezer MJ, de Reuver PR, van Grevenstein WMU, Hemmer PHJ, Punt CJA, Tanis PJ, Mols F, de Hingh IHJT; Dutch Peritoneal Oncology Group and the Dutch Colorectal Cancer Group. Perioperative Systemic Therapy Versus Cytoreductive Surgery and HIPEC Alone for Resectable Colorectal Peritoneal Metastases: Patient-Reported Outcomes of a Randomized Phase II Trial. Ann Surg Oncol. 2023;30:2678-2688. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kalkdijk-Dijkstra AJ, van der Heijden JAG, van Westreenen HL, Broens PMA, Trzpis M, Pierie JPEN, Klarenbeek BR; FORCE Trial Group. Pelvic floor rehabilitation to improve functional outcome and quality of life after surgery for rectal cancer: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial (FORCE trial). Trials. 2020;21:112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 24. | De Crignis L, Slim K, Cotte E, Meillat H, Dupré A. Impact of surgical indication on patient outcomes and compliance with enhanced recovery program for colorectal surgery: A Francophone multicenter retrospective analysis. J Surg Oncol. 2020;122:928-933. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/