Published online Oct 7, 2025. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v31.i37.110786

Revised: July 14, 2025

Accepted: August 27, 2025

Published online: October 7, 2025

Processing time: 102 Days and 12.9 Hours

Studies investigating diagnostic delays and their effects on patients with alcoholic cirrhosis.

To investigate the current status and associated factors influencing diagnostic del

A cross-sectional analysis was conducted at a tertiary hospital in China from June 2020 to December 2023. Data were collected through telephone follow-ups and questionnaires. The Wilcoxon and Kruskal-Wallis H tests were used to compare diagnostic delays across various characteristics. Multivariate linear regression was employed to identify factors associated with diagnostic delays.

The median diagnostic delay was 5 months, with an interquartile range of 2-11 months. The proportions of patients with alcoholic cirrhosis who initially visited tertiary, secondary, and primary hospitals were 38.9%, 37.91%, and 23.19%, re

Our study indicates that patients with alcoholic cirrhosis may experience varying degrees of diagnostic delay. Interventions targeting potential factors contributing to diagnostic delay are necessary.

Core Tip: Among 401 patients with alcoholic cirrhosis in China, the median diagnostic delay was 5 months, with significant variations induced by hospital level (tertiary vs primary) and liver computed tomography evaluation. Factors contributing to diagnostic delay included residence, education, income, drinking patterns and initial diagnostic measures. Lower education, higher daily alcohol intake, lower income and elevated blood ammonia were identified as independent predictors on mul

- Citation: Dai ZS, Gao Z, He B, Jiang YF. Diagnostic delays in alcoholic cirrhosis: A cross-sectional study of contributing factors. World J Gastroenterol 2025; 31(37): 110786

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/1007-9327/full/v31/i37/110786.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v31.i37.110786

Alcoholic liver disease is an emerging substantial global health concern that is largely attributed to widespread alcohol abuse, its high incidence and mortality rates[1,2]. Alcoholic cirrhosis is one of the main causes of liver-related deaths and accounts for half of all cirrhosis-related deaths, especially in areas with high alcohol consumption[3,4]. According to the 2018 Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health, approximately 3 million people worldwide die each year due to excessive drinking, comprising 5.3% of all deaths and 47.9% of all liver cirrhosis-related deaths[5]. Early detection and intervention for alcoholic cirrhosis are critical in preventing disease progression.

Between 2005 and 2016, the per capita consumption of alcohol among individuals aged 15 years and above in China rose by 76%. The 2022 World Health Organization statistical report indicated that with a per capita alcohol consumption of 6.0 L, surpassing the global average of 5.8 L, the incidence of alcoholic cirrhosis in China has rapidly increased[4,6]. However, early diagnosis of alcoholic cirrhosis is often delayed due to a combination of patient-related factors, disparities between healthcare providers and numerous social factors.

Medical-seeking behaviour encompasses the entire process from recognising symptoms to seeking medical care, with the aim of preventing or detecting diseases early and facilitating treatment. Timely medical consultation is key to early intervention and improved patient outcomes. A study indicates that quitting alcohol may help improve survival prognosis at any disease stage in patients with alcoholic diseases. The longer a patient delays quitting drinking, the higher the risk of complications, comorbidities and mortality, and the weaker the benefits of quitting[7]. Another study confirmed that quitting alcohol within a month after early diagnosis of liver cirrhosis can increase the 7-year life expectancy 1.6-fold[8]. Diagnostic delay is the interval between the appearance of symptoms and the diagnosis of a disease. Although a study found that mild clinical symptoms detected early often lead to delayed diagnosis and treatment of alcoholic liver cirrhosis, the study did not delve into the clinical characteristics and associated factors contributing to delayed diagnosis[9]. Despite its importance, studies on diagnostic delays and associated factors in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis in China are scarce. Given the numerous individuals affected by alcoholic cirrhosis in China, this study investigated the medical-seeking behavior of these patients and explored the factors influencing diagnostic delays, which may facilitate early diagnosis and timely intervention.

This cross-sectional, real-world study assessed hospitalised patients with alcoholic cirrhosis in a large tertiary teaching hospital in China. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Second Xiangya Hospital of Central South University, No. 2020-047. All study participants obtained written informed consent. The study was conducted following the ethical guidelines set forth in the Helsinki Declaration.

All participants were hospitalised in the Department Infection Diseases, Xiangya Second Hospital between June 2020 and December 2023. The eligibility criteria were as follows: (1) Aged over 18 years and at least 5 years of alcohol consumption; (2) Alcoholic cirrhosis diagnosed upon hospitalisation using laboratory and comprehensive clinical and imaging data; (3) Absence of serious comorbid conditions, such as brain, lung, heart, kidney or hematopoietic diseases; (4) Ability to complete survey questionnaires; and (5) No missing diagnostic delay data. Patients not meeting any of these criteria were excluded from the study.

The following data were collected at the initial visit: Age, race, sex, residence, years of education, resident type, family size, marital status, annual family income, diagnostic delay, medical insurance, first diagnosis, hospital classification for the first visit, years of drinking, daily alcohol consumption, type of alcohol consumed, previous history of liver computed tomography (CT) and liver colour ultrasound, hepatic encephalopathy level, ascites level, and hepatic and renal function. Diagnostic delay was defined as the time between the onset of symptoms and the physician-confirmed diagnosis of alcoholic cirrhosis, measured in months[10]. The primary data collection methods included self-completion questionnaires, self-reported information and clinical records. Trained research assistants collected the data, which were subsequently verified by liver disease specialists.

Data analysis was performed using SPSS version 21.0 and R software version 3.6.2. A normality test revealed that the data were non-normally distributed. Continuous variables are reported as medians and interquartile ranges (IQR), while categorical variables are expressed as n (%). Diagnostic delay, categorised using the clinical characteristics of inpatients, was compared using the Wilcoxon and Kruskal-Wallis H tests. Spearman’s rank correlation and multivariate linear regression analyses were performed to further investigate the factors linked to diagnostic delay. A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

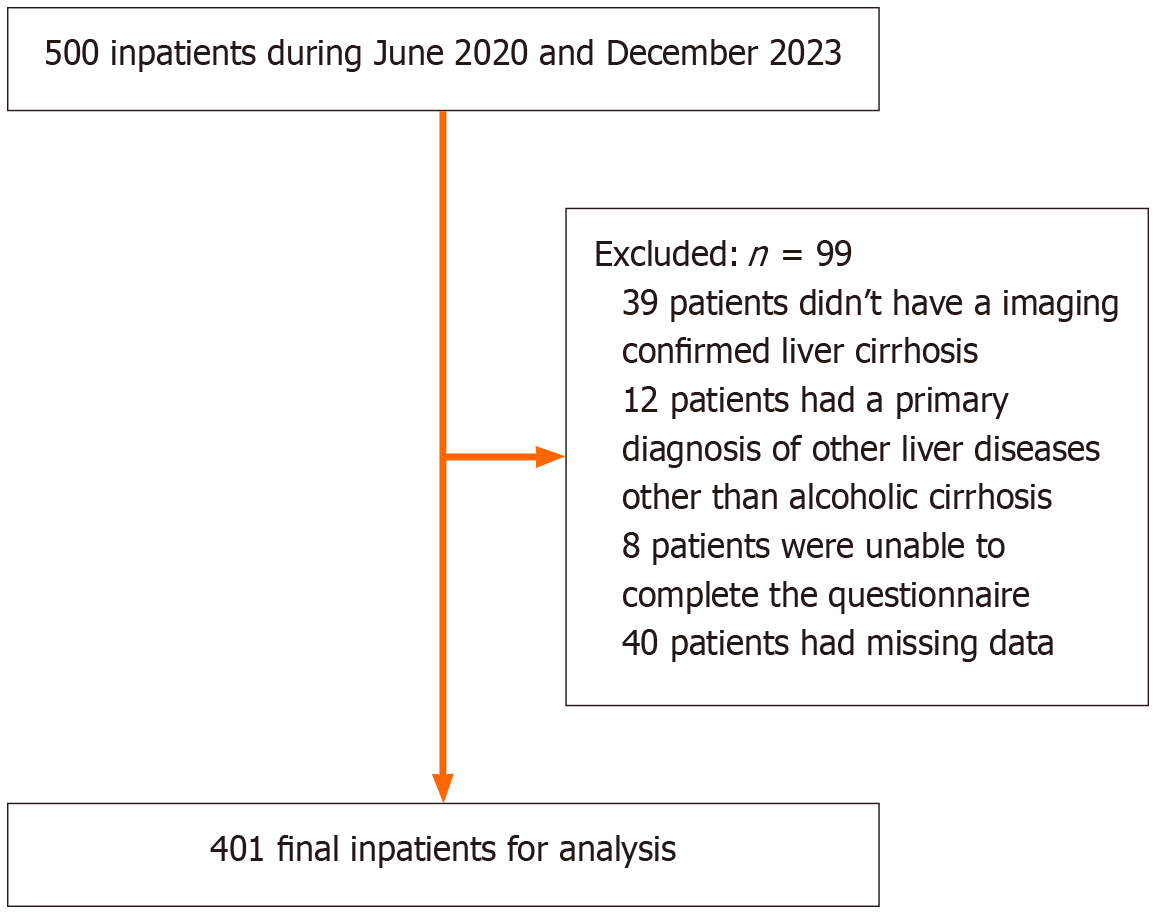

Out of the original cohort of 500 inpatients, 99 were excluded. Of these, 39 Lacked imaging-confirmed liver cirrhosis, 12 were diagnosed with other liver diseases unrelated to alcoholic cirrhosis, 8 could not complete the questionnaire, and 40 had incomplete data. Ultimately, 401 patients who met the study criteria were included in the analysis (Figure 1). Table 1 summarises the demographic and clinical characteristics of the included patients. Of the total population, 96.76% were male, while 3.24% were female. The majority (82.54%) had not been diagnosed with alcoholic cirrhosis for the first time. Almost all patients (96.01%) were Han Chinese, and 83.54% were married. More than half of the participants resided in urban areas, while 43.39% lived in rural regions. Approximately 77.31% of the patients lived with family members, while 22.69% lived alone. A large proportion (90.77%) had medical insurance, whereas 9.23% did not have coverage. Over one-third (38.9%) sought care at tertiary hospitals for their initial diagnosis. Most patients (75.06%) underwent liver colour ultrasound examination on their initial visit, while less than half (41.65%) underwent liver CT. Furthermore, 56.61% of the patients reported Baijiu (Chinese liquor) as their drink type, followed by rice wine (28.43%). The majority (88.78%) of patients did not have concurrent hepatic encephalopathy, with only 10.22% having grade 1-2 hepatic encephalopathy. More than half of the patients had mild or above-average ascites, with the majority of patients having varying degrees of albumin deficiency. The median diagnostic delay was 5 months (IQR: 2-11 months). The proportion of patients diagnosed with alcoholic cirrhosis during their first visit increased progressively with the hospital level (P < 0.001; Table 2). Furthermore, the frequency of liver colour ultrasound and liver CT performed during the initial visit significantly increased in higher-level hospitals (P < 0.001; Tables 3 and 4).

| Characteristics | n = 401 |

| First diagnosis | |

| Yes | 70 (17.46) |

| No | 331 (82.54) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 388 (96.76) |

| Female | 13 (3.24) |

| Age (years) | 57 (50-65) |

| Race | |

| Han | 385 (96.01) |

| Miao | 8 (1.99) |

| Zhuang | 1 (0.25) |

| Tujia | 5 (1.25) |

| Others | 2 (0.5) |

| Marital status | |

| Married | 335 (83.54) |

| Unmarried | 6 (1.50) |

| Widowed | 34 (8.48) |

| Divorced | 26 (6.48) |

| Family size (population) | 2 (2-2) |

| Drinking ml-day | 500 (250-800) |

| Drinking years | 30 (20-40) |

| Residence | |

| City | 227 (56.61) |

| Rural area | 174 (43.39) |

| Resident manner | |

| Living alone | 91 (22.69) |

| Not living alone | 310 (77.31) |

| Years of education | 9 (6-12) |

| Average annual family income (ten thousand RMB) | 4 (2-6) |

| Medical insurance | |

| Yes | 364 (90.77) |

| No | 37 (9.23) |

| Diagnostic delay (months) | 5 (2-11) |

| Hospital classification for first visit | |

| First-level hospital (I) | 93 (23.19) |

| Secondary hospital (II) | 152 (37.91) |

| Tertiary hospital (III) | 156 (38.9) |

| Receiving liver color ultrasound in the first visit | |

| Yes | 301 (75.06) |

| No | 100 (24.94) |

| Receiving liver-computed tomography test in the first visit | |

| Yes | 167 (41.65) |

| No | 234 (58.35) |

| Types of wine | |

| Baijiu (Chinese liquor) | 227 (56.61) |

| Red wine | 2 (0.50) |

| Beer | 2 (0.50) |

| Rice wine | 114 (28.43) |

| Baijiu and rice wine | 29 (7.23) |

| Baijiu and beer | 20 (5.00) |

| Baijiu and red wine | 1 (0.25) |

| Baijiu, beer and rice wine | 5 (1.25) |

| Baijiu, red wine and rice wine | 1 (0.25) |

| Hepatic encephalopathy level | |

| No | 356 (88.78) |

| 1-2 Level | 41 (10.22) |

| 3-4 Level | 4 (1.00) |

| Ascites level | |

| No | 171 (42.64) |

| Mild | 169 (42.14) |

| Moderate to severe | 61 (15.21) |

| Albumin level | |

| Normal | 61 (15.21) |

| Moderate deficiency | 171 (42.64) |

| Mild deficiency | 169 (42.15) |

| The first diagnosis of proportion | First-level hospital (I), n = 93 | Secondary hospital (II), n = 152 | Tertiary hospital (III), n = 156 | P value |

| Yes | 0 (0) | 8 (11.43) | 62 (88.57) | < 0.001 |

| No | 93 (28.10) | 144 (43.50) | 94 (28.40) |

| Proportion | First-level hospital (I), n = 93 | Secondary hospital (II), n = 152 | Tertiary hospital (III), n = 156 | P value |

| Yes | 4 (4.3) | 145 (95.39) | 152 (97.44) | < 0.001 |

| No | 89 (95.7) | 7 (4.61) | 4 (2.56) |

| Proportion | First-level hospital (I), n = 93 | Secondary hospital (II), n = 152 | Tertiary hospital (III), n = 156 | P value |

| Yes | 1 (1.08) | 21 (13.82) | 145 (92.95) | < 0.001 |

| No | 92 (98.92) | 131 (86.18) | 11 (7.05) |

Table 5 presents the results of the Wilcoxon test, conducted to examine differences in diagnostic delay between groups defined by binary variables. Diagnostic delay differed significantly between area of residence, living status, time of diagnosis, medical insurance status and liver colour ultrasound/Liver CT during the first visit (all P < 0.001). Table 6 presents the findings of the Kruskal-Wallis H analysis, highlighting differences in diagnostic delays among different categories of variables. Significant differences (all P < 0.01) were found according to age, years of education, family size, marital status, annual family income, years of drinking, daily alcohol consumption and type of drink.

| Characteristics | Diagnostic delay (months) | P value |

| Sex | ||

| Male | 5 (2-11) | 0.737 |

| Female | 5 (1-11) | |

| Residence | ||

| Rural area | 11 (6-19.75) | < 0.001 |

| City | 2 (0.7-5) | |

| Resident manner | ||

| Living alone | 18 (10-23) | < 0.001 |

| Not living alone | 4 (1-7) | |

| First diagnosis | ||

| Yes | 1 (0.325-4) | < 0.001 |

| No | 6 (2-12) | |

| Medical insurance | ||

| Yes | 4 (1-9) | < 0.001 |

| No | 23 (18-28) | |

| Receiving liver-computed tomography test in the first visit | ||

| Yes | 2 (0.6-5) | < 0.001 |

| No | 7 (4-13) | |

| Receiving liver color ultrasound in the first visit | ||

| Yes | 3 (1-7) | < 0.001 |

| No | 14 (9-22.25) |

| Characteristics | Diagnostic delay (months) | P value |

| Age | ||

| < 50 years | 3 (1-7) | |

| 50-60 years | 5 (2-10) | < 0.001 |

| 60-70 years | 7 (2-14) | |

| ≥ 70 years | 8 (0.8-23) | |

| Years of education | ||

| ≤ 6 years | 10 (6-16) | |

| 7-9 years | 5 (3-8) | < 0.001 |

| 10-12 years | 2 (0.925-4) | |

| ≥ 12 years | 0.5 (0.2-1.0) | |

| Family size | ||

| 1 population | 12 (6-21.25) | |

| 2-3 populations | 5 (1.5-11) | < 0.01 |

| > 3 populations | 2 (1.25-6) | |

| Marital status | ||

| Married | 4 (1-9) | |

| Unmarried | 18 (13.5-20.25) | < 0.001 |

| Widowed | 19 (11-24) | |

| Divorced | 15 (7.5-23) | |

| Average annual family income | ||

| < 2 ten thousand RMB/year | 20.5 (12.75-24.5) | |

| 2-4 ten thousand RMB/year | 8 (5-12) | |

| 4-6 ten thousand RMB/year | 4 (2-8) | |

| 6-8 ten thousand RMB/year | 2 (0.775-4) | < 0.001 |

| > 8 ten thousand RMB/year | 0.5 (0.2-0.8) | |

| Drinking years | ||

| < 10 years | 9 (6.5-9.5) | |

| 10-20 years | 2 (1-6) | |

| 20-30 years | 4 (1-7) | |

| 30-40 years | 6 (2-11) | < 0.001 |

| 40-50 years | 7 (2-15) | |

| > 50 years | 20 (1-28) | |

| Drinking mL-day | ||

| < 100 mL | 4 (4-4) | |

| 100-250 mL | 0.2 (0.2-0.9) | |

| 250-500 mL | 2 (0.6-5) | |

| 500-1000 mL | 5 (2-10) | < 0.001 |

| > 1000 mL | 14 (8-23) | |

| Types of wine | ||

| Baijiu | 3 (0.9-6) | |

| Red wine | 0.6 (0.4-0.8) | |

| Beer | 12.5 (6.75-18.25) | |

| Rice wine | 12 (6-18) | < 0.001 |

| Various wines | 6 (2-13) |

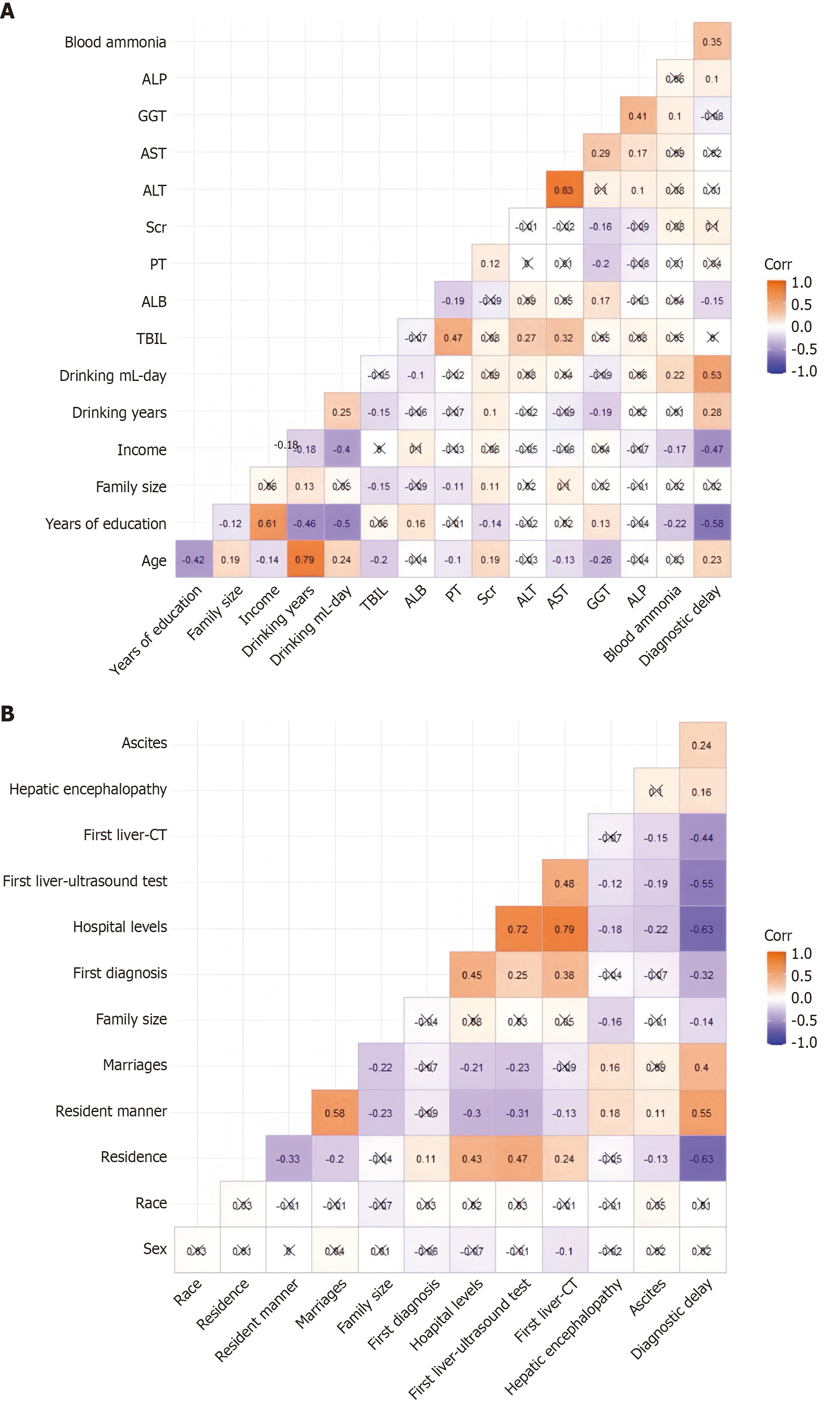

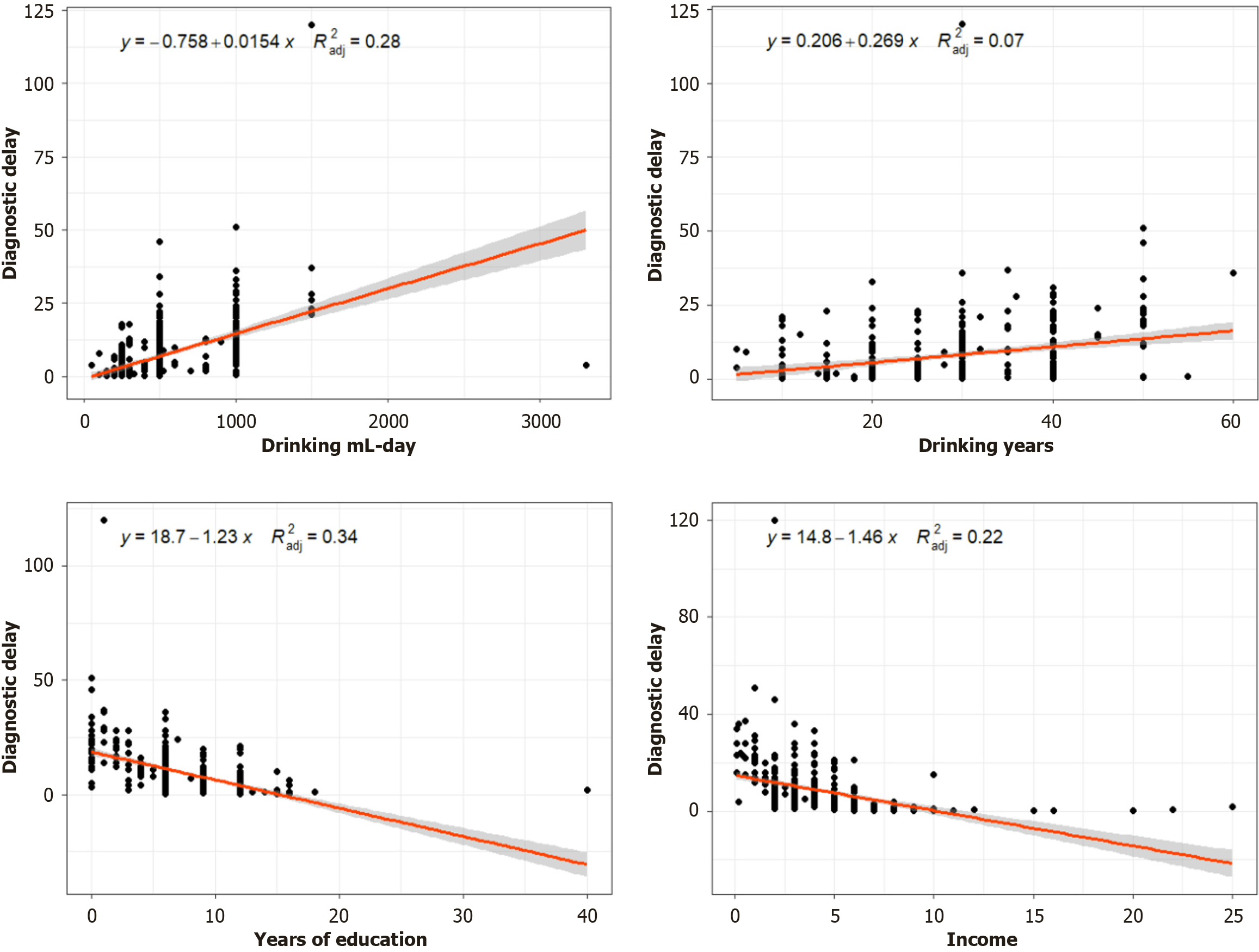

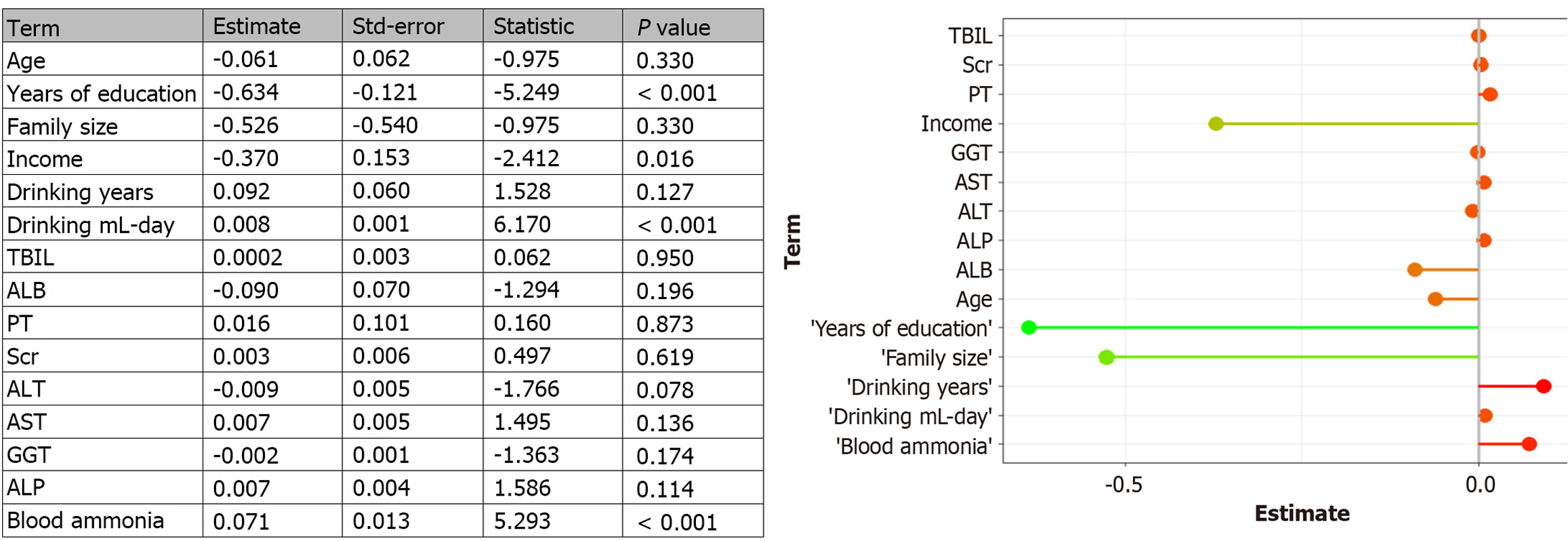

Furthermore, diagnostic delay was associated to varying degrees with daily alcohol consumption and other characteristic variables, including residence, years of drinking, medical insurance, years of education, annual family income and undergoing liver CT and colour ultrasound on the first visit (P < 0.01; Figures 2 and 3). Figure 4 illustrates the results of multivariate linear regression analysis that examined factors potentially influencing diagnostic delay. This analysis identified years of education (P < 0.01), daily alcohol consumption (P < 0.01), annual family income (P < 0.05) and blood ammonia levels (P < 0.01) as significant predictors of diagnostic delay.

To our knowledge, this is the first study to analyse the diagnostic delay in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis and contributing factors. Patients with alcoholic cirrhosis showed varying degrees of diagnostic delay [median (IQR): 5 (2-11) months]. A study indicated that the median diagnostic delay for arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy was 8 years[11]. Another multi-centre study from 13 paediatric centres in Italy showed that the median overall diagnostic delay of coeliac disease in children was 5 months (IQR: 2-11 months), which is similar to our results[12]. A recent multi-centre study in Turkey found that the average diagnostic delay was 35.1 months (median: 12 months) in 1134 patients with psoriatic arthritis. Within a 3-month period, approximately 39% of individuals were diagnosed with the condition, while a larger proportion, 67%, obtained a diagnosis within a 2-year timeframe[13]. In our study, only 17.46% of patients were diagnosed with alcoholic cirrhosis on their first visit, which may be because alcoholic cirrhosis is a chronic disease caused by long-term alcohol consumption and dependence, with indistinct symptoms. Therefore, patients often lack proactive medical behaviour, leading to delayed diagnosis and treatment.

Our study found significant differences based on liver colour ultrasound and CT examinations performed by different levels of medical institutions for patients with alcoholic cirrhosis on their first visit, which may also lead to differences in the first diagnosis rate in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis among different levels of hospitals. The low diagnostic rate among patients with alcoholic cirrhosis in primary medical institutions may result from a lack of diagnostic equipment, creating difficulty in the timely diagnosis of the patient’s liver condition. Furthermore, although some primary medical institutions are equipped with colour ultrasound equipment, the imperfect technology and lack of experienced technicians are also significant factors affecting the accuracy of ultrasound examinations. Therefore, no consensus has been reached on using ultrasound examination as a non-invasive method for diagnosing cirrhosis in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis[14].

We found that diagnostic delay increased with age, which may be associated with age-related cognitive decline[15]. Diagnostic delay of alcoholic cirrhosis also differed between rural and urban residents, which may be due to significant differences in medical allocation between rural and urban areas. Our findings also indicate that patients living alone have a longer diagnostic delay than those who live with others, possibly due to fewer opportunities for physical health testing and family care, as well as a higher risk of depression, which affects their ability to seek medical attention[16,17]. Dia

Interestingly, low-dose alcohol consumption and years of drinking often prolong diagnostic delay. This may be due to the tendency of patients and doctors to overlook alcoholic liver cirrhosis, resulting in delayed diagnosis. Conversely, individuals with lower alcohol consumption and shorter drinking histories are more prone to misdiagnosis, given the atypical nature of their clinical presentation. The cumulative damage of alcohol use on neuropsychological function increases with the amount and years of alcohol consumption, leading to longer diagnostic delay[18,19]. Furthermore, beer and rice wine were more likely to cause protracted diagnostic delay than other types of alcohol, possibly because drinks with lower alcohol content are less likely to elicit an acute alcoholic reaction, thereby increasing patients’ tendency to ignore symptoms caused by alcoholic cirrhosis. Previous studies have positively correlated blood ammonia levels with the degree of cirrhosis, related complications and mortality[20]. Our study further revealed a strong correlation between diagnostic delay and blood ammonia levels. Therefore, we hypothesised that a longer delayed diagnosis worsens the degree of cirrhosis in patients, leading to higher blood ammonia levels during hospitalisation.

Our study has some limitations. First, the cohort was not population-based, as participants were recruited from a single tertiary hospital in China. Therefore, this result may not accurately reflect the characteristics of diagnostic delay in all Chinese patients with alcoholic cirrhosis. Sex and ethnic disparities also affect healthcare accessibility, symptom presentation and the social determinants influencing diagnostic timelines, thereby potentially limiting the generalisability of our findings. Nonetheless, we maintain that our results carry significant clinical relevance. Our study provides an objective assessment of the current state of patients with alcoholic cirrhosis in Hunan, offering insights into the clinical features of these patients and the factors contributing to diagnostic delay. Further multi-centre collaborative studies involving a broader range of populations are essential to confirm and expand upon our initial findings. Second, diagnostic delays and certain issues identified in this study are inherently subjective, as patients may forget or inaccurately recall their symptoms and diagnosis over time. Some patients with asymptomatic alcoholic cirrhosis may interfere with the results of a diagnostic delay. However, in this study, such patients were very few and did not bias the results of the study. Furthermore, telephone follow-ups and self-reported questionnaires could introduce recall bias, particularly in patients with a history of chronic alcohol use and potential cognitive impairments. These individuals might experience difficulty in accurately recalling the onset of initial symptoms or the timing of their final diagnosis. In future studies, we aim to incorporate more objective data collection methods to minimise the impact of recall bias on the assessment of diagnostic delays. Third, future studies should investigate other factors that may contribute to diagnostic delays in individuals with alcoholic cirrhosis. Qualitative studies or more in-depth follow-up investigations could uncover valuable insights into the complex interactions among the factors influencing diagnostic delays in patients with alcoholic cirrhosis, guiding the development of more targeted and effective clinical interventions. The diagnostic capabilities of primary care hospitals must be strengthened to enhance the identification of early signs of liver cirrhosis, along with the implementation of a nationwide screening system for populations at high risk of alcohol abuse, thereby minimising diagnostic delays.

Our study revealed that patients with alcoholic cirrhosis experience diagnostic delays to varying degrees. Factors such as educational level, daily alcohol consumption, annual household income, and blood ammonia levels were predictive of these delays. Interventions targeting these potential factors must be implemented to reduce diagnostic delays.

We would like to thank all participants for collecting the data for this study.

| 1. | Asrani SK, Mellinger J, Arab JP, Shah VH. Reducing the Global Burden of Alcohol-Associated Liver Disease: A Blueprint for Action. Hepatology. 2021;73:2039-2050. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 107] [Article Influence: 21.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Gao B, Bataller R. Alcoholic liver disease: pathogenesis and new therapeutic targets. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1572-1585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1244] [Cited by in RCA: 1544] [Article Influence: 102.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 3. | Blachier M, Leleu H, Peck-Radosavljevic M, Valla DC, Roudot-Thoraval F. The burden of liver disease in Europe: a review of available epidemiological data. J Hepatol. 2013;58:593-608. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 879] [Cited by in RCA: 919] [Article Influence: 70.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 4. | Rehm J, Samokhvalov AV, Shield KD. Global burden of alcoholic liver diseases. J Hepatol. 2013;59:160-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 475] [Cited by in RCA: 550] [Article Influence: 42.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 5. | Yan C, Hu W, Tu J, Li J, Liang Q, Han S. Pathogenic mechanisms and regulatory factors involved in alcoholic liver disease. J Transl Med. 2023;21:300. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | World Health Organization. World health statistics 2022: monitoring health for the SDGs, sustainable development goals. May 19, 2022. [cited 14 May 2025]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240051157. |

| 7. | Borowsky SA, Strome S, Lott E. Continued heavy drinking and survival in alcoholic cirrhotics. Gastroenterology. 1981;80:1405-1409. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 8. | Verrill C, Markham H, Templeton A, Carr NJ, Sheron N. Alcohol-related cirrhosis--early abstinence is a key factor in prognosis, even in the most severe cases. Addiction. 2009;104:768-774. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 95] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Huang J, Yu J, Wang J, Liu J, Xie W, Li R, Wang C. Novel potential biomarkers for severe alcoholic liver disease. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1051353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Dai Z, Ma Y, Zhan Z, Chen P, Chen Y. Analysis of diagnostic delay and its influencing factors in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a cross-sectional study. Sci Rep. 2021;11:14213. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Tini G, Graziosi M, Musumeci B, Targetti M, Russo D, Parisi V, Argirò A, Ditaranto R, Leone O, Autore C, Olivotto I, Biagini E. Diagnostic delay in arrhythmogenic cardiomyopathy. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2023;30:1315-1322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Bianchi PI, Lenti MV, Petrucci C, Gambini G, Aronico N, Varallo M, Rossi CM, Pozzi E, Groppali E, Siccardo F, Franchino G, Zuccotti GV, Di Leo G, Zanchi C, Cristofori F, Francavilla R, Aloi M, Gagliostro G, Montuori M, Romaggioli S, Strisciuglio C, Crocco M, Zampatti N, Calvi A, Auricchio R, De Giacomo C, Caimmi SME, Carraro C, Staiano A, Cenni S, Congia M, Schirru E, Ferretti F, Ciacci C, Vecchione N, Latorre MA, Resuli S, Moltisanti GC, Abruzzese GM, Quadrelli A, Saglio S, Canu P, Ruggeri D, De Silvestri A, Klersy C, Marseglia GL, Corazza GR, Di Sabatino A. Diagnostic Delay of Celiac Disease in Childhood. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7:e245671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kılıç G, Kılıç E, Tekeoğlu İ, Sargın B, Cengiz G, Balta NC, Alkan H, Kasman SA, Şahin N, Orhan K, Gezer İA, Keskin D, Mülkoğlu C, Reşorlu H, Ataman Ş, Bal A, Duruöz MT, Kücükakkaş O, Şen N, Toprak M, Yurdakul OV, Melikoğlu MA, Ayhan FF, Baykul M, Bodur H, Çalış M, Çapkın E, Devrimsel G, Hizmetli S, Kamanlı A, Keskin Y, Ecesoy H, Kutluk Ö, Şendur ÖF, Tolu S, Tuncer T, Nas K. Diagnostic delay in psoriatic arthritis: insights from a nationwide multicenter study. Rheumatol Int. 2024;44:1051-1059. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Shiha G, Sarin SK, Ibrahim AE, Omata M, Kumar A, Lesmana LA, Leung N, Tozun N, Hamid S, Jafri W, Maruyama H, Bedossa P, Pinzani M, Chawla Y, Esmat G, Doss W, Elzanaty T, Sakhuja P, Nasr AM, Omar A, Wai CT, Abdallah A, Salama M, Hamed A, Yousry A, Waked I, Elsahar M, Fateen A, Mogawer S, Hamdy H, Elwakil R; Jury of the APASL Consensus Development Meeting 29 January 2008 on Liver Fibrosis With Without Hepatitis B or C. Liver fibrosis: consensus recommendations of the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver (APASL). Hepatol Int. 2009;3:323-333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kurihara K, Shiroma A, Koda M, Shinzato H, Takaesu Y, Kondo T. Age-related cognitive decline is accelerated in alcohol use disorder. Neuropsychopharmacol Rep. 2023;43:587-595. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Zheng G, Zhou B, Fang Z, Jing C, Zhu S, Liu M, Chen X, Zuo L, Chen H, Hao G. Living alone and the risk of depressive symptoms: a cross-sectional and cohort analysis based on the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study. BMC Psychiatry. 2023;23:853. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Cao W, Cao C, Ren B, Yang J, Chen R, Hu Z, Bai Z. Complex association of self-rated health, depression, functional ability with loneliness in rural community-dwelling older people. BMC Geriatr. 2023;23:267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Saunders PA, Copeland JR, Dewey ME, Davidson IA, McWilliam C, Sharma V, Sullivan C. Heavy drinking as a risk factor for depression and dementia in elderly men. Findings from the Liverpool longitudinal community study. Br J Psychiatry. 1991;159:213-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 133] [Cited by in RCA: 111] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Nixon SJ, Garcia CC, Lewis B. Women's use of alcohol: Neurobiobehavioral concomitants and consequences. Front Neuroendocrinol. 2023;70:101079. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Tranah TH, Ballester MP, Carbonell-Asins JA, Ampuero J, Alexandrino G, Caracostea A, Sánchez-Torrijos Y, Thomsen KL, Kerbert AJC, Capilla-Lozano M, Romero-Gómez M, Escudero-García D, Montoliu C, Jalan R, Shawcross DL. Plasma ammonia levels predict hospitalisation with liver-related complications and mortality in clinically stable outpatients with cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2022;77:1554-1563. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 23.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/