Published online Dec 18, 2025. doi: 10.13105/wjma.v13.i4.112603

Revised: August 22, 2025

Accepted: December 5, 2025

Published online: December 18, 2025

Processing time: 139 Days and 21.6 Hours

Clinical predictors of dengue fever are crucial for guiding timely management and avoiding life-threatening complications. While prognostic scores are avai

To evaluate the performance and accuracy of various proposed dengue clinical prognostic scores.

Three databases, PubMed, EMBASE and Cochrane, were searched for peer-re

Most commonly studied outcomes were severe dengue (15 models) and mortality (8 models). For the paediatric population, Bedside Dengue Severity Score by Ga

While several models demonstrated precision and reliability in predicting severe dengue and mortality, broader application across diverse geographic settings is needed to assess their external validity.

Core Tip: This is a comprehensive systematic review to evaluate and compare the accuracy of prognostic models in both adult and paediatric populations with dengue fever. Out of 29 included studies comprising over 17000 patients, we highlight models that demonstrated high specificity and sensitivity. Notably, the Bedside Dengue Severity Score by Gayathri et al and the nomogram by Nguyen et al performed best among paediatric models, while Leo et al’s and Lee et al’s models showed outstanding performance in adult populations. This nuanced breakdown by demographic and model performance offers actionable insights not previously synthesized in the literature.

- Citation: Thangaraja K, Heng JYJ, Basker G, Chong ST, See KC. Clinical prognostic scores for dengue fever: A systematic review. World J Meta-Anal 2025; 13(4): 112603

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2308-3840/full/v13/i4/112603.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.13105/wjma.v13.i4.112603

Dengue incidence has been on the rise globally with both geographic expansion and a shift from urban to rural settings, with a burden of disease from eight countries studied in the period 2001-2005 estimated at USD 440 million[1]. Dengue infection has varied clinical manifestations from asymptomatic, mild fever, to fatal disease[2] and is often unpredictable in its evolution[1]. The predictability of the critical phase in patients remains especially elusive[3]. The hallmarks of severe dengue include severe plasma leakage, organ impairment, or bleeding[4], with several individual risk factors identified by World Health Organization (WHO) as warning signs[1], but utility of each sign may vary across different populations[5]. Besides the severity of dengue, it may also be important to consider predictors of clinical outcomes, such as mortality and length of stay, to better provide timely and tailored management.

While there have been many recent studies identifying the multitude of clinical predictors of dengue severity[6], few synthesise simple prognostication models or systems that allow for efficient decision-making regarding admission, monitoring, and therapy intensity. Additionally, given how dengue is hyperendemic in some of the poorest regions of the world[1,2], this is also helpful in the just allocation of scarce resources.

Therefore, this systematic review aims to evaluate different prognostic clinical scores for dengue by assessing their performance and accuracy on patients diagnosed with dengue fever. Moreover, a detailed evaluation of the studies’ characteristics will be informative towards commenting on their generalisability, thereby allowing this review to identify the most robust and applicable tool in dengue prognostication in varied contexts.

A protocol for the study was published on PROSPERO (registration number CRD42024547027).

We systematically searched PubMed, EMBASE and Cochrane from inception to 4 September 2023 to obtain studies either developing or validating prognostic models relevant to dengue fever.

We included all studies that reported the development and/or validation of clinical scoring models for prognostic outcomes of patients diagnosed with dengue fever who were admitted and received adequate clinical treatment. The inclusion and exclusion criteria of this review are shown in Table 1.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | |

| Population/problem | Patients primarily diagnosed with dengue fever through: Serum non-structural protein 1 antigen positivity or IgM and IgG antibodies to dengue virus or dengue virus RNA by real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction | Patients diagnosed with other febrile illnesses |

| Intervention/exposure | Prognostic clinical scoring systems for dengue fever. Predicted outcomes of the models include any possible clinical endpoints of Dengue Fever such as dengue severity, critical outcomes, probability of intensive care unit outcomes or mortality rates | Scores for purposes other than prognostication e.g. diagnosis etc. Scores that are not specific to dengue fever. Non-clinical scoring systems |

| Control/comparison | Nil | Nil |

| Outcome | Accuracy of prognostic scoring | Nil |

| Study design | Articles in English/translated into English Observational studies (prospective and retrospective cohort). Randomised controlled trials | Articles not written in English/no available English translation Systematic reviews and meta-analyses. Review articles. Case series, case reports |

A standardised data extraction was independently conducted by at least two of the first four authors for each included article. The following information was extracted: Authors, year of publication, title, journal, study type, paediatric only, sample size of patients diagnosed with dengue fever, age in years (mean ± SD), number and proportion of males, day of illness, symptoms at presentation, method of dengue diagnosis, 1997 WHO classification and 2009 WHO classification, duration of hospitalisation (days), mortality (%), intensive care unit (ICU) admissions (%), prognostic score characteristics (such as score type, score components, detailed descriptions of score and predicted/prognostic outcomes), and prognostic score performance markers (such as sensitivity, specificity, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC), positive predictive value, negative predictive value.

Two researchers, Basker G and Chong CS, independently conducted the assessment of risk of bias of the prognostic models using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) (Supplementary Table 1)[7]. An adaptation of the NOS was used for assessment of cross-sectional studies (Supplementary Table 2). Disagreements were resolved with the last author.

No patients or the public were involved in the formulation or execution of this research study.

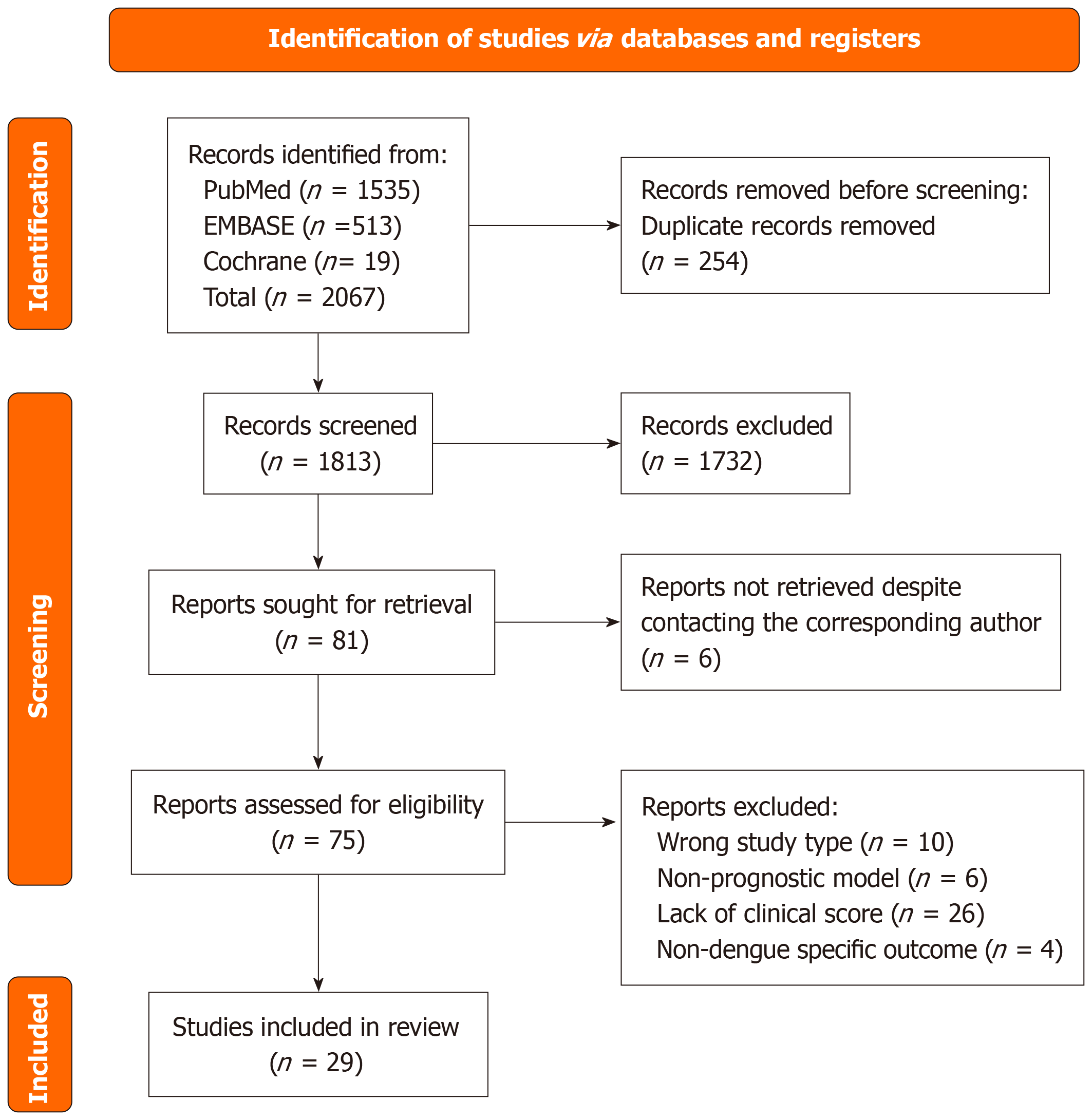

The PRISMA flow diagram outlining study selection is presented in Figure 1[8]. Literature search of three databases (PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane) retrieved a total of 2067 studies, of which 254 duplicate articles were removed. The remaining 1813 articles underwent a first sieve based on study titles and abstracts. 81 studies were shortlisted and we were unable to find full text of 6 articles, despite contacting the corresponding authors of these papers. 75 articles were retrieved and sieved further based on full-text screening. 46 studies were excluded due to reasons including wrong study type, non-prognostic models, wrong outcomes, or a lack of clinical scoring system. The resulting 29 articles were included in this systematic review.

The risk of bias assessment is reported in Supplementary Tables 3 and 4[9]. Overall, no studies presented a significant risk of bias.

A total of 17910 participants across the 29 studies published from 2010 to 2023 were included in this systematic review. Of the 29 included studies, there were 13 prospective cohort studies (44.8%)[10-22], 12 retrospective cohort studies (41.4%)[23-34], 2 case control studies (6.9%)[35,36], and 2 cross-sectional studies (6.9%)[37,38]. Table 2 summarises the characteristics and demographics of the included studies.

| Ref. | Period of data collection | Location | Study type | Model | Validation | Sample size |

| Chi et al[38], 2023 | 1 July 2015 to 30 November 2015 | Tainan, Taiwan | Retrospective cross-sectional | Multivariate binary logistic regression with significant coefficient transformed to scores by inverse odds ratio | External validation (separate region and time) | 701 |

| Yang et al[37], 2023 | August 15, 2019 and September 30, 2019 | Dhaka, Bangladesh | Cross-sectional | CART model used on univariate and multivariate logistic regression models | Internal validation via split-sample with random assignment (80% training sample, 20% hold-out sample) | 1090 |

| Gayathri et al[10], 2023 | Model: October 2019; Validation: September 2019 to January 2021 | Chennai, India | Prospective cohort | Binary logistic regression to develop prediction severity model with forward stepwise method in 3 steps to identify 3 significant variables and Nagelkerke square to quantify influence of variables | Temporal validation on 2021 data (n = 312) | 312 |

| McBride et al[11], 2022 | June 2019 to June 2021 | Ho Chi Minh city, Vietnam | Prospective observational cohort | mSOFA score and delta excluding bilirubin calculated from day 0 and 2. Brier score rescaled from 0 to 1 | Internal validation via bootstrap procedure with 500 resamples with replacement | 124 |

| Bhaskar et al[12], 2022 | January 2016 to December 2020 | Manipal, India | Prospective case cohort | Logistic regression model of significant variables | No validation | 303 |

| Srisuphanunt et al[23], 2022 | 2017 to 2019 | Bangkok, Thailand | Retrospective cohort | Potential predictor tested for trend with nonparametric method | Internal validation (method not mentioned) | 302 |

| Sachdev et al[13], 2021 | July 1, 2016 to December 31, 2019 | New Deli, India | Prospective cohort | Multivariate logistic regression model to identify independent risk factors, stepwise entry of new terms into model | No validation | 78 |

| Marois et al[24], 2021 | January 1, 2017 to July 31, 2017 | New Caledonia | Retrospective cohort | Predictive model built using multiple logistic regression and descending stepwise analysis | Internal validation via k-fold cross-validation (k = 10) | 383 |

| Devarbhavi et al[25], 2020 | January 2014 to December 2017 | Bangalore, India | Retrospective cohort | MELD score, arterial pH, lactate used to generate ROC with C-statistics | No validation | 36 |

| Tangnararatchakit et al[26], 2020 | 2004 to 2018 | Bangkok, Thailand | Retrospective cohort | Daily Dengue severity score created in Phase I (n = 191) | Temporal validation on Phase II (n = 51) | 242 |

| Lee et al[27], 2018 | Kaohsiung Chang Gung Memorial Hospital: 2022 to 2015; Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital[2]: 2009 to 2013 | Kaohsiung, Taiwan | Retrospective cohort | Multivariate logistic regression model and assigning points by dividing its regression coefficient by smallest coefficient in model (rounded to nearest whole number) | No validation | 1068 |

| Phakhounthong et al[28], 2018 | October 12, 2009 to October 12, 2010 | Siem Reap, Cambodia | Retrospective cohort | CART tree constructed with J48 algorithm to generate decision tree | Internal validation via 10-fold cross-validation by Weka sed to estimate out-of-sample accuracy (split data into 10, 9 for training, 1 for testing). Multiple rounds of cross-validation performed using different partitions | 198 |

| Park et al[14], 2018 | Queen Sirikit National Institute of Child Health[3]: 1994 to 1997, 1999 to 2002, 2004 to 2007; Kamphaeng Phet Provincial Hospital[4]: 1994 to 1997 | Bangkok, Thailand; Nai Mueang, Thailand | Prospective cohort | SEM using data from n = 257 with complete data | Internal validation via multiple imputation via Markov-chain Monte Carlo method to create 50 imputed datasets without missing data on n = 1244 to assess Sn | 744 |

| Md-Sani et al[29], 2018 | September 8, 2022 to November 18, 2022 | Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia | Retrospective cohort | Variable selection via 5-fold cross-validated Lasso regression used to build logistic regression model | Internal validation via cross-validation | 199 |

| Suwarto et al[30], 2018 | January 2011 to March 2016 | Jarkarta, Indonesia | Retrospective cohort | Dengue Score (Suwarto et al[18], 2016) | External validation | 207 |

| Hsieh et al[15], 2017 | July 1, 2015 to December 31, 2015 | Tainan, Taiwan | Prospective cohort | Univariate and multivariate with binary variables Cox model to identify predictive factors for mortality with cut-off values selected using Youden index | No validation | 625 |

| Huang et al[35], 2017 | September 1, 2015 to December 31, 2015 | Tainan, Taiwan | Case control | Univariate analysis and Multivariate logistic regression analysis to investigate independent predictors for 30-day mortality. Novel prediction score developed by assigning a score of 1 to each independent variable | Internal validation via bootstrapping method by generating 1000 hypothetical study population using random sampling from study sample | 2358 |

| Fernández et al[31], 2017 | 2009 to 2010 | Tegucigalpa and San Pedro Sula, Honduras | Retrospective cohort | Univariable analysis and multivariable logistic regression analysis using forward stepwise selection to construct a predictive model for severe dengue | Internal validation via bootstrap technique (sampling with replacement using 320 individuals sampling 1000 times) | 320 |

| Nguyen et al[16], 2017 | October 1, 2010 to December 31, 2013 | Southern Vietnam | Prospective cohort | Logistic regression to develop prognostic model | Internal validation via "leave-one-site-out cross validation" (develop algorithm on all but 1 study site and validate using that study site) and Temporal validation | 2060 |

| Djossou et al[17], 2016 | March 17, 2013 to September 30, 2013 | Cayenne, French Guiana | Prospective cohort | Final model include variables with significant association in single covariable analysis | Internal validation via bootstrapping 1000 replications | 806 |

| Lee et al[32], 2016 | Kaohsiung Chang Gung Memorial Hospital: July 1, 2002 to May 31, 2015; Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital[6]: 2009 to 2011 | Kaohsiung, Taiwan | Retrospective cohort | Significant variables in univariate analysis entered into multivariate logistic regression and point assignment calculated by dividing regression coefficient by smallest coefficient in model | Temporal validation (model set before 31 Jul 2014 n = 1063, validation set after Aug 1 2014 n = 190) | 1253 |

| Suwarto et al[18], 2016 | March 2010 to August 2015 | Jarkarta, Indonesia | Prospective cohort | Variables entered into multiple regression analysis using backward selection algorithm to estimate coefficient and independent diagnostic predictors and converted into simplified risk score system | Validation published separately[30] | 172 |

| Lam et al[19], 2015 | 2003 to 2009 | Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam | Prospective cohort | Univariate and multivariate analysis via logistic regression and model simplified using stepwise backwards model selection based on Akaike Information Criterion | Temporal validation (model from n = 939 enrolled before 2009 and validated on 268 enrolled during 2009) and internal validation via repeated 10-fold cross-validation | 1207 |

| Pang et al[36], 2014 | January 1, 2004 to December 31, 2008 | Singapore | Case control | Univariate and multivariate conditional logistic regression performed to assess association | No validation | 135 |

| Pongpan et al[33], 2014 | 2007 to 2010 | Phrae, Thailand; Lamphun, Thailand; Chiang Mai, Thailand | Retrospective cohort | Scoring system (Pongpan et al[34], 2013) | External validation | 400 |

| Pongpan et al[34], 2013 | 2007 to 2010 | Nakorn Sawan, Thailand; Kampaeng Phet, Thailand; Uttaradit, Thailand | Retrospective cohort | Scoring system analysed by multivariable ordinal logistic regression and assigned item scores derived from coefficient transformation | Validation published separately[33] | 777 |

| Leo et al[20], 2013 | January 2010 to September 2012 | Singapore | Prospective cohort | Variables selected from World Health Organization[7] Warning Signs | External validation | 499 |

| Diaz-Quijano et al[21], 2010 | Not reported | Bucaramanga, Colombia | Prospective cohort | Risk score based on independent predictors and risk group formed | No validation | 729 |

| Potts et al[22], 2010 | Queen Sirikit National Institute of Child Health: 1994 to 1997, 1999 to 2002, 2004 to 2007; Kamphaeng Phet Provincial Hospital: 1994 to 1997 | Bangkok, Thailand; Kamphaeng Phet, Thailand | Prospective cohort | CART analysis with age, gender, and clinical laboratory data to establish a diagnostic decision tree | Internal validation via k-fold cross validation method (k = 5) of each tree | 582 |

The participant baseline characteristics are outlined in Table 3. There were a total of 7051 males (51.1%) (summarised from 25 studies[10-13,15,17-20,23-38]) consisting of participants from both adults and paediatric studies, although the mean ages cannot be reliably summarised due to incomplete data.

| Ref. | Paediatrics only | n | Age | Gender (male) | Ethnicity | Social demographics | Onset | Presentation |

| Chi et al[38], 2023 | No | 701 | 54.1 ± 19.2 | 363 (51.8) | Nil | Nil | Nil | Fever, nausea, vomit, bleeding, fatigue, hyporexia, abdominal pain (data not available) |

| Yang et al[37], 2023 | No | 1090 | < 18 years: 318 (29.2). 18-39 years: 553 (50.7). ≥ 40 years: 219 (20.1) | 652 (59.8) | Nil | Uneducated: 28 (26.1). Primary education: 339 (31.1). Secondary education: 306 (28.1). Tertiary education: 112 (10.3). Missing education data: 49 (4.5). Low income (< 15000 BDT per month): 34 (31.4). Low-mid income (15000-25000 BDT per month): 404 (37.1). High-mid income (25000-50000 BDT per month): 206 (18.9). High income (≥ 50000 BDT per month): 71 (6.5). Missing income data: 67 (6.1). Slum: 384 (35.2). Flat: 540 (49.5). House: 125 (11.5). Missing residence data: 41 (3.8) | Nil | Fever, myalgia, vomit, headache, abdominal pain |

| Gayathri et al[10], 2023 | Yes | 312 | 6.4 ± 3.44 | 196 (62.8) | Nil | Nil | Nil | Fever, bleeding, vomit, fatigue, abdominal pain |

| McBride et al[11], 2022 | No | 124 | 24.5, IQR: 20-32 | 63 (50.8) | Nil | Nil | Median 5 days (range 3-7) | Nil |

| Bhaskar et al[12], 2022 | Yes | 303 | ≤ 6 years: 60 (19.8). > 6 years: 243 (80.2) | 161 (53.1) | Nil | Nil | Nil | Headache, myalgia, abdominal pain, rash, vomit, dyspnoea |

| Srisuphanunt et al[23], 2022 | No | 302 | 24.9 ± 17.3 | 154 (50.1) | Nil | Nil | Nil | Nil |

| Sachdev et al[13], 2021 | Yes | 78 | 10, IQR: 6.2-12 | 49 (62.8) | Nil | Nil | 4.44 ± 2.15 | Nil |

| Marois et al[24], 2021 | No | 383 | 32, IQR: 34 | 174 (45.4) | Melanesian: 141 (36.7). European: 86 (22.5). Polynesian: 68 (17.8). Others: 63 (17.4) | Tobacco: 105 (27.4). Cannabis: 19 (4.9). Kava: 15 (3.9). Alcohol (> 3 units/day): 9 (2.3) | Median 4 days, IQR: 3 | Fever, arthralgia, myalgia, eye pain, headache, diarrhoea, nausea, vomit, rash, third spacing, fatigue, hepatomegaly, abdominal pain |

| Devarbhavi et al[25], 2020 | No | 36 | 32.31 ± 17.04 | 20 (55.6) | Nil | Nil | Range 3 to 7 days | Nil |

| Tangnararatchakit et al[26], 2020 | Yes | 242 | 10.6 ± 3.9 | 137 (56.6) | Nil | Nil | Nil | Nil |

| Lee et al[27], 2018 | No | 1068 | 52, IQR: 18-91 | 513 (47.2) | Nil | Nil | Median 3 days (range 1-10) | Fever, myalgia, arthralgia, eye pain, rash, headache, cough, diarrhoea, vomit, fatigue, abdominal pain |

| Phakhounthong et al[28], 2018 | Yes | 198 | 1 month-< 1 year: 56 (28.2). 1 year < 5 year: 59 (29.8). ≥ 5 years: 83 (41.9) | 107 (54.0) | Nil | Nil | < 2 days | Fever, vomit, bleeding, dyspnoea, hepatomegaly, headache, rash, altered mental state |

| Park et al[14], 2018 | Yes | 744 | Validation set not reported) | Nil | Nil | Nil | < 3 days | Fever |

| Md-Sani et al[29], 2018 | No | 199 | 30.8, IQR: 24.7-41.3 | 127 (63.8) | Nil | Nil | Nil | Fever, vomit, bleeding, fatigue, hepatomegaly, third spacing |

| Suwarto et al[30], 2018 | No | 207 | 33, IQR: 23-46 | 91 (44) | Nil | Nil | Nil | Fever |

| Hsieh et al[15], 2017 | No | 625 | 72.3 ± 9.3 | 46 (61.3) | Nil | Nil | Nil | Nil |

| Huang et al[35], 2017 | No | 2358 | 47.8 ± 21.9 | 1197 (50.8) | Nil | Stay with family: 2296 (97.4). Stay alone: 53 (2.2). Long-term care: 9 (0.4). Tobacco: 47 (2). Alcoholism: 34 (1.4) | Nil | Fever, arthralgia, myalgia, eye pain, headache, nausea, vomit, bleeding, rash, hyporexia, diarrhoea, fatigue, cough, dizzy, altered mental state, dyspnoea, chest pain, abdominal pain |

| Fernández et al[31], 2017 | No | 320 | 22.4 (missing SD) | 181 (56.6) | Nil | Nil | ≥ 6 days | Fever, headache, eye pain, arthralgia, myalgia, rash, vomit, hyporexia |

| Nguyen et al[16], 2017 | Yes | 2060 | Given as 2 cohorts in median IQR | Nil | Nil | Nil | < 3 days | Fever |

| Djossou et al[17], 2016 | No | 806 | < 1 year: 23 (2.9). 1-15 year: 294 (36.5). 16-65 year: 480 (59.6). > 65 years: 15 (1.9) | 408 (50.2) | Nil | Nil | Median 2 days | Myalgia, arthralgia, bleeding, rash, vomit, abdominal pain (data not available) |

| Lee et al[32], 2016 | No | 1253 | Given as 2 cohorts in median IQR | 595 (47.5) | Nil | Nil | Derivation cohort Median 4 days, range 1-15. Validation cohort. Median 4 days, range 1-13 | Nil |

| Suwarto et al[18], 2016 | No | 172 | 22, IQR: 11-33 | 89 (51.7) | Nil | Nil | 3 days | Fever |

| Lam et al[19], 2015 | Yes | 1207 | 10, IQR: 7-12 | 645 (53) | Nil | Nil | Median 5 days (IQR: 5-6) | Fever, bleeding, third spacing, abdominal pain |

| Pang et al[36], 2014 | No | 135 | Given as 2 cohorts in median IQR | 88 (65.2) | Chinese: 98 (72.6). Malay: 7 (5.2). Indian: 17 (12.6). Others: 13 (9.6) | Nil | Cases: 3 days (IQR: 3-5). Control: 5 days (IQR: 4-5) | Nil |

| Pongpan et al[33], 2014 | Yes | 400 | 10.3 ± 3.4 | 223 (55.8) | Nil | Nil | Nil | Vomit, cough, bleeding, hepatomegaly, headache, myalgia, rash, third spacing, abdominal pain |

| Pongpan et al[34], 2013 | Yes | 777 | 9.6 ± 3.3 | 376 (48.4) | Nil | Nil | Nil | Hepatomegaly, headache, myalgia, vomit, cough, rash, third spacing, bleeding, abdominal pain |

| Leo et al[20], 2013 | No | 499 | Given as 2 cohorts in median IQR | 396 (79.4) | Nil | Nil | ED cohort. Median 6 days (5%-95% 3-8). Outpatient cohort. Median 6 days (5%-95% 3-8) | Nil |

| Diaz-Quijano et al[21], 2010 | No | 729 | 25.8 ± 15.9 | Nil | Nil | Nil | Median: 7 days; range: 4-10 | Fever, headache, eye pain, myalgia, arthralgia, hyporexia, cough, rash, vomit, diarrhoea, bleeding, abdo pain |

| Potts et al[22], 2010 | Yes | 582 | 8.7 ± 0.5 | Nil | Nil | Nil | Mean 2.15 days | Fever |

Dengue diagnosis was confirmed via serology for immunoglobulin against dengue virus in 21 studies (75.9%)[10,12-17,19,21-23,25-29,31,32,35,36,38], NS1 antigen testing in 19 studies (65.5%)[10,12,13,15-18,20,23,25-30,32,35,37,38], reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction in 14 studies (44.8%)[13-20,22,24,27,32,36,38], and viral isolation in 4 studies (13.8%)[14,21,22,31], while 2 studies (6.9%)[33,34] extracted the diagnosis via electronic medical records. Recruited patients presented with a range of symptoms, in descending order from the most reported: Fever (85.6%), vomiting in 14 studies (43.3%), abdominal pain in 12 studies (42.3%), headache reported in 10 studies (47.5%), and myalgia reported in 10 studies (48.7%).

Comorbidities of the participants reported included diabetes mellitus (n = 752 of 6722, 11.2%, from 8 studies[15,24,27,29,32,35,36,38]), hypertension (n = 1150 of 6021, 19.1%, from 7 studies[15,24,27,29,32,35,36]), and chronic kidney disease/end-stage renal failure (n = 165 of 6388, 2.58%, from 6 studies[15,24,27,32,35,38]).

The most common prognostic outcomes were severe dengue (15 models[10,14,16,17,19,20,22-24,26,28,32-34,37]) and mortality (8 models[11,13,15,25,27,29,35,38]). Severe dengue was often defined according to the 2009 WHO Classification, or as dengue haemorrhagic fever or dengue shock syndrome following the older 1997 WHO Classification.

ICU outcomes were predicted by 2 models[11,36]. Pang et al’s model predicted the probability of patients requiring ICU admission[36], while the model by McBride et al[11] was able to prognosticate multiple outcomes in relation to ICU admission, including duration of admission, organ support requirements and duration of intravenous fluid therapy.

The remaining models were designed to predict specific clinical outcomes. Hypotension, including threatened and profound shock, was covered by a few studies and was the main predicted outcome in the model by Djossou et al[17]. The score developed by Diaz-Quijano et al[21] focused on predicting bleeding manifestations, and was able to do so for acute febrile syndrome in dengue and non-dengue diagnoses. Finally, Suwarto et al[30] created a Dengue Score which could predict plasma leakage manifestations such as pleural effusion and ascites in patients with dengue.

The majority of studies utilised univariate and multivariate regression models to identify factors independently associated with their respective outcomes in order to generate prognostic models. These models were then converted into assigned integer scores or nomograms which are easily utilised in the clinical setting. 3 studies[22,28,37] developed classification and regression tree (CART) prognostic models for dengue fever. Predictor variables included both baseline clinical characteristics and laboratory test results, and the predicted outcome for all 3 CART models was severe dengue.

Three studies[11,15,25] utilised existing clinical scores to predict outcomes in patients with dengue fever. McBride et al[11] developed a modified Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score for dengue fever which was made more specific to dengue by adding pulse pressure to the cardiovascular assessment to reflect physiological compensation during profound plasma leakage, and changing the PaO2/FiO2 ratio to SpO2/FiO2 given that obtaining arterial blood gas is often avoided in dengue patients due to thrombocytopenia. Hsieh et al[15] utilised both the SOFA and Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) II scores, calculated within the first 24 hours of ICU admission, in their study. They showed that either APACHE II score > 24 or SOFA score > 15 was associated with in-hospital fatality, and linked to acute respiratory failure, acute kidney injury and cardiac arrest. Lastly, Devarbhavi et al[25] found that in patients with dengue hepatitis presenting with acute liver failure, the model for end-stage liver disease (MELD) score on admission was a significant predictor of mortality.

Of the total 27 scores proposed, 11 (40.7%) received only internal validations, 3 (11.1%) with only temporal validations, 2 (7.4%) with both internal and temporal validation, 4 (14.8%) with only external validations, and 7 (25.9%) had no validations mentioned.

Of the 29 included studies, 11 studies (37.9%)[10,12-14,16,19,22,26,28,33,34] focused solely on dengue fever in the paediatric population, defined as participants under 18 years of age in this paper. This accounts for 6661 (37.2%) participants out of the total 17910 patients. Fever was the most common presenting symptom along with vomiting, abdominal pain and bleeding manifestations.

Nine out of the 10 paediatric models created were designed to predict severe or complicated dengue in children, including manifestations such as profound or recurrent shock, dengue hemorrhagic fever or dengue shock syndrome. Only one model created by Sachdev et al[13] predicted mortality in children with dengue fever, although the study only included children admitted to the paediatric ICU.

The results of the prognostic score performance have been summarised in Table 4. Models developed by Chi et al[38] for critical outcomes, McBride et al[11] for duration of ICU, organ support requirement, IV therapy duration, Mortality, Lee et al[27] for mortality at 3, 7 days and overall (Supplementary Figure 1), Park et al[14] for severity, Md-Sani et al[29] for mortality, and Pang et al[36] for ICU requirement attained an AUC value of above 0.9.

| Ref. | Model | Score components | Predicted outcomes | Threshold | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) |

| Leo et al[20], 2013 | Number of warning signs | Abdominal pain; Persistent vomiting; Clinical fluid accumulation; Mucosal bleeding; Hepatomegaly (> 2 cm); ↑ in hematocrit; rapid ↓ of platelet | DHF I-IV and severe dengue | Nil | 1 warning sign: DHF I-IV 79%. DHF II-IV 100%. Severe dengue 100%. 2 warning signs: DHF I-IV 33%, DHF II-IV 47%, Severe dengue 46%. 3 warning signs: DHF I-IV 6%, DHF II-IV 9%, Severe dengue 8% | 1 warning sign: DHF I-IV 52%, DHF II-IV 52%, Severe dengue 48%. 2 warning signs: DHF I-IV 88%, DHF II-IV 88%, Severe dengue 85%. 3 warning signs: DHF I-IV 99%, DHF II-IV 99%, Severe dengue 98% |

| Chi et al[38], 2023 | Multivariable binary logistic regression | Clinical presentations; age; chronic comorbidities, such as DM, CKD, chronic heart failure, and neoplasms; and abnormal laboratory finding | Critical outcomes early identification and treatment | 4 | 95.7% | 76.8% |

| Lee et al[27], 2018 | Regression equation | Serum bicarbonate; ALT; age; gender | Mortality | 2 | 94.9% | 85.2% |

| Suwarto et al[30], 2018 | Nomogram | Hct; Serum Albumin; Platelet count; AST ratio | Pleural effusion and/or ascites | ≥ 2 | 92.45 | 74.26 |

| Huang et al[35], 2017 | Nomogram | Elderly age (≥ 65 years); Hypotension (systolic blood pressure < 90 mmHg); hemoptysis; DM; chronic bedridden | Mortality | 1 and 3 | Score ≥ 1: 91.2% | Score ≥ 3: 99.7% |

| Sachdev et al[13], 2021 | Outcome predictor variables | SGPT; S lactate; PRISM 12 (paediatric risk of mortality at 12 hours admission); VIS (vasopressor inotrope score); FB (fluid balance % at 24 hours) | Mortality | S lactate: 2.73 mmol/L, VIS: 22.5 | S lactate: 0.90 | VIS: 0.948 |

| Pang et al[36], 2014 | Prognostic index (equation) | Neutrophil proportion; ALT; serum urea level | ICU requirement | P = −1.4 | 88.2 | 88.9 |

| Nguyen et al[16], 2017 | Nomogram | Vomiting; PLT; n × AST ULN; NS1 +ve | Severe Dengue | Nil | 0.87 | 0.88 |

| Gayathri et al[10], 2023 | Binary logistic regression | Bedside dengue severity score = -1.297 + 4.234 (narrow pulse pressure) + 1.284 (mucosal bleed) + 0.489 (third space fluid loss) | Severe dengue | Nil | 86.75% | 98.25% |

| Tangnararatchakit et al[26], 2020 | Nomogram | Age ≤ 1 year; aspirin or nonsteroidal drug ingestion; underlying disease such as hemolytic anaemia and congenital heart disease; additional vital signs; urine output; bleeding sites; amounts of the required crystalloid; colloid and blood components; inotropic drug administration; respiratory support and invasive procedures | Subsequent threatened shock and profound shock | ≥ 12 | 86.21 | 84.26 |

| Marois et al[24], 2021 | Sex-specific multivariable predictive model | Female model: Age class; Medical history; Hypertension (treated/untreated); Symptoms-Mucosal bleeding, clinical liquid accumulation, skin rash (except purpura); last biological results-Platelets < 30 g/L, ALT > 10 N. Male model: Age class; Risky behaviour; Alcohol abuse > 3 u/day; symptoms mucosal bleeding; last biological results-Platelets < 30 g/L, ALT > 10N | Severe dengue | Nil | Female model: 84.5%. Male model: 84.5% | Female model: 78.6%. Male model: 95.5% |

| Bhaskar et al[12], 2022 | Multivariable binary regression model | PCV; Platelet count; ALT; Highest WBC; Hypotension | Complicated dengue in paediatric patients | 2 | 84.1 | 72.5 |

| Suwarto et al[18], 2016 | Nomogram | Hct; Serum Albumin; Platelet count; AST ratio | Pleural effusion/or ascites | ≥ 2 | 82.47 | 70.42 |

| Devarbhavi et al[25], 2020 | MELD score | Admission lactate | Mortality | Nil | 81% | 74% |

| Park et al[14], 2018 | Structural equation modelling | Any dengue illness; AST, WBC; %lymphocytes; PLT; tourniquet test at fever day -3 and -1 | DF, DHF vs DSS | 0.587 | 80.4 | 80.4 |

| Fernández et al[31], 2017 | Univariable and multivariable logistic regression | Headache; petechiae; ascites; platelets < 50000 platelets/mm3 at baseline | Plasma leakage | 7% | 76.4 | 70.3 |

| Lee et al[32], 2016 | Multivariable model based on disease duration | Model 1 age (≥ 65 years vs < 65 years); minor gastrointestinal bleeding (present vs absent); leukocytosis WBC > 10 × 109 cells/L (present vs absent); Platelet count ≥ 100 × 109 cells/L (present vs absent) | Severe dengue | 1 | 70.3% | 90.6% |

| Phakhounthong et al[28], 2018 | CART (classification and regression tree) | HCT; GCS; urine protein; Cr; PLT | Severe dengue | 0.5 | 0.605 | 0.65 |

| Djossou et al[17], 2016 | Logistic regression model | Hematocrit increase; protein concentration; sodium concentration; lymphocyte count; age; aches; extensive purpura; Rash; serous effusion; bleeding | Shock | Nil | 48.2 | 94.2 |

| Yang et al[37], 2023 | CART and random forest model | Age; dyspnoea; plasma leakage; lowest platelet | Severe dengue | Nil | Nil | Nil |

| McBride et al[11], 2022 | Nomogram | SpO2/FiO2; platelet count; Bilirubin level; MAP/PP; Adrenergic agents; GCS score; Creatinine and urine output | Duration of ICU admission Requirement for organ support (mechanical ventilation, vasopressors, renal replacement therapy). Duration of intravenous fluid therapy. Death | Nil | Nil | Nil |

| Srisuphanunt et al[23], 2022 | Nomogram | Albumin; AST; ALT; PLT; PTT; DENV IgM | Severe dengue | Nil | Nil | Nil |

| Md-Sani et al[29], 2018 | Regression equation | Serum bicarbonate; ALT; age; gender | Mortality | Nil | Nil | Nil |

| Hsieh et al[15], 2017 | Multivariate Cox model | APTT; SOFA; APACHE II scores | Mortality | Nil | Nil | Nil |

| Lam et al[19], 2015 | Nomogram | Age; day of illness; pulse rate; temperature; hematocrit; hemodynamic index | Profound DSS, Recurrent shock | Nil | Nil | Nil |

| Pongpan et al[33], 2014 | Nomogram | Age; Hepatomegaly; SBP; WBC; PLT | DF, DHF vs DSS | Nil | Nil | Nil |

| Pongpan et al[34], 2013 | Nomogram | Age; Hepatomegaly; HCT; SBP; WBC; PLT | DF, DHF vs DSS | Nil | Nil | Nil |

| Diaz-Quijano et al[21], 2010 | Binomial regression | Age between 12 and 45 years, rash; vomiting; temperature > 38 °C; leukocyte count < 4500/L; platelet count < 90.000/L | Bleeding | Nil | Nil | Nil |

| Potts et al[22], 2010 | CART | (1) WBC; %monocytes; PLT; HCT; and (2) WBC; AST; %neutrophil; PLT; Age | Severe Dengue (DSS vs DHF Grade 3/4, or PEI > 15) | Nil | Nil | Nil |

Outcomes analysed by the proposed models included severity of disease including complications of shock[14,16,19,22,26,28,33,34], and mortality[13].

The model with the highest specificity for severe dengue was by Gayathri et al[10] (specificity = 0.9825, 95%CI: 0.9556-0.9952) (Supplementary Figure 2). Aside from pulse pressure, other components were consistent with WHO Dengue warning signs[1]. This included third-spacing and mucosal bleeding, although other warning signs were more specific and also differed for other paediatric ages[5]. Meanwhile, the most sensitive model for dengue severity was by Nguyen et al[16] (sensitivity = 0.87) (Supplementary Figure 3). The variables similarly included WHO Dengue warning signs[1] of vomiting, and also platelet count which were separately reported to have high negative predictive values[5]. Additionally, raised aspartate transaminase (AST) was associated with dengue severity in children as a marker of liver injury[39] and was found to rise before alanine transaminase (ALT)[40]. Meanwhile NS1 status correlated with severity for primary infections[41] which were also more likely in children. These scores further refine the implementation of WHO warning signs in evaluating for Dengue severity and progression.

On the other hand, mortality prediction was only evaluated by the Vasopressor Inotrope Score (VIS) (Supplementary Figure 4) with a specificity of 0.948. This is consistent with VIS being a measure of haemodynamic support[42], and is used in the prediction of mortality across other causes and ages, including cardiovascular disease such as Cardiac Arterial Bypass Graft in adults (specificity = 0.88)[43], Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation in paediatrics (specificity = 0.82)[44], and for sepsis (specificity = 0.83)[45]. Moreover, the most sensitive model as reported by Sachdev et al[13] and children[46,47]. This is because lactate in both young and old is indicative of not only the degree of anaerobic respiration as with tissue hypoxia (i.e. shock), but may also contribute to severe lactic acidosis[48].

For disease severity and complications, the most specific model was reported by Leo et al[20] with a specificity of 98% for severe dengue (Supplementary Figure 5). As with the paediatric population, the WHO warning signs, while nonspecific when assessed individually, are closely associated with dengue severity[1,49], although a combination may improve their specificity[20]. In contrast, the most sensitive scores were the warning signs for severe dengue as reported by Leo et al[20], where all Warning Signs except lethargy were included (Supplementary Figure 6) as well as Model 2 by Lee et al[20], with a sensitivity of 100% (Supplementary Figure 7). For the latter, older adults were at higher risk[50] possibly because of the higher possibility of secondary infection[51], while leukocytosis may relate to severity from its apparent link with bacterial superinfection or dyserythropoiesis[40].

With regards to mortality, the most specific model was a quantitative integer scoring as proposed by Huang et al[35] (Supplementary Figure 8), and is linked with poor morbidity and mortality especially in the elderly with comorbidities[52,53]. Simultaneously, hypotension may be a manifestation of distributive shock[54]. Therefore, there is clear preceding evidence which supports these predictive variables in measuring the mortality risk. Alternatively, the most sensitive was Model 3 by Lee et al[27,32] with leukocytosis especially identified as a red flag[55,56] while gastrointestinal bleeding may be precipitated by and thus an indicator of severe thrombocytopenia[57]. Furthermore, as these measures are already routine in dengue, it is also simpler to integrate them for use in the clinical context.

Lastly, specificity and sensitivity of the predictive model relating to ICU stay were only reported in one study by Pang et al[36] (sensitivity 88.2%, specificity 88.9%) (Supplementary Figure 9). Neutrophils are a significant contributor to dengue pathophysiology, including viral clearance and mediating dengue severity via vascular permeability or cardiac complications[58]. Likewise, ALT is associated with bleeding and hepatic impairment[40,59], while serum urea has been implicated in increased agglutination[60] and may suggest involvement of acute kidney impairment[61]. Therefore, these explain the relevance of neutrophils, ALT, and serum urea in determining the need for closer monitoring and timely interventions in the ICU.

In examining the variables used in dengue prognostication, there were several common factors including clinical features of gastrointestinal bleeding and hypotension, as well as laboratory results such as platelet count and evidence of acute kidney injury or liver impairment, in keeping with previous reviews identifying individual factors. However, paediatric ages, gender, secondary infection, other WHO warning signs, and biomarkers like Serum albumin, AST, or C-reactive protein[6,62,63] were missing. Therefore, it may be pertinent that future research incorporates these variables to ascertain their efficacy in prognosticating dengue infections.

Firstly, few prognostic scores rely solely on clinical information. This thus limits the utility of such prognostication, especially in rural or primary care settings with scarce resources. Secondly, decision-analytic evaluations of prognostic models were absent. It is important to additionally measure the net benefit and compare against reference strategies to guide protocol and algorithm generation[64]. This is because while these scores may perform well in correlating to clinical outcomes, they may not sufficiently inform clinicians on the most appropriate management to then carry out.

In conclusion, despite the increasing prevalence and severity of dengue, there appears to be a paucity in well-validated instruments for dengue prognostication. This paper evaluates different proposed prognostic clinical scores via assessing their prognostic performance and accuracy. While several models were found to be accurate in predicting severe dengue and mortality, they have to be applied in wider contexts and different geographical locations to better evaluate their external validity.

| 1. | World Health Organization. Dengue: Guidelines for Diagnosis, Treatment, Prevention and Control. 2009. [cited 6 November 2025]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241547871. |

| 2. | Wills B, Leo Y. Dengue. In: Firth J, Conlon C, Timothy Cox T, editors. Oxford Textbook of Medicine. Oxford, 2020. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 3. | Tayal A, Kabra SK, Lodha R. Management of Dengue: An Updated Review. Indian J Pediatr. 2023;90:168-177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yacoub S, Farrar J. A 16-year-old Girl from Vietnam with Fever, Headache and Myalgias. Clinical Cases in Tropical Medicine. London, United Kingdom: W.B. Saunders, 2015: 72-74. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 5. | Karyanti MR, Uiterwaal CSPM, Hadinegoro SR, Widyahening IS, Saldi SRF, Heesterbeek JAPH, Hoes AW, Bruijning-Verhagen P. The Value of Warning Signs From the WHO 2009 Dengue Classification in Detecting Severe Dengue in Children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2024;43:630-634. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Sangkaew S, Ming D, Boonyasiri A, Honeyford K, Kalayanarooj S, Yacoub S, Dorigatti I, Holmes A. Risk predictors of progression to severe disease during the febrile phase of dengue: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21:1014-1026. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 33.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | The Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses. [cited 6 November 2025]. Available from: https://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp. |

| 8. | PRISMA 2020 flow diagram. [cited 6 November 2025]. Available from: https://www.prisma-statement.org/prisma-2020-flow-diagram. |

| 9. | Liu X, Yu N, Lu H, Zhang P, Liu C, Liu Y. Effect of opioids on constipation in critically ill patients: A meta-analysis. Aust Crit Care. 2024;37:338-345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Gayathri V, Lakshmi SV, Murugan SS, Poovazhagi V, Kalpana S. Development and Validation of a Bedside Dengue Severity Score for Predicting Severe Dengue in Children. Indian Pediatr. 2023;60:359-363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | McBride A, Vuong NL, Van Hao N, Huy NQ, Chanh HQ, Chau NTX, Nguyet NM, Ming DK, Ngoc NT, Nhat PTH, Phong NT, Tai LTH, Tho PV, Trung DT, Tam DTH, Trieu HT, Geskus RB, Llewelyn MJ, Thwaites CL, Yacoub S. A modified Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score for dengue: development, evaluation and proposal for use in clinical trials. BMC Infect Dis. 2022;22:722. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Bhaskar M, Mahalingam S, M M H, Achappa B. Predictive scoring system for risk of complications in pediatric dengue infection. F1000Res. 2022;11:446. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sachdev A, Pathak D, Gupta N, Simalti A, Gupta D, Gupta S, Chugh P. Early Predictors of Mortality in Children with Severe Dengue Fever: A Prospective Study. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2021;40:797-801. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Park S, Srikiatkhachorn A, Kalayanarooj S, Macareo L, Green S, Friedman JF, Rothman AL. Use of structural equation models to predict dengue illness phenotype. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018;12:e0006799. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hsieh CC, Cia CT, Lee JC, Sung JM, Lee NY, Chen PL, Kuo TH, Chao JY, Ko WC. A Cohort Study of Adult Patients with Severe Dengue in Taiwanese Intensive Care Units: The Elderly and APTT Prolongation Matter for Prognosis. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:e0005270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Nguyen MT, Ho TN, Nguyen VV, Nguyen TH, Ha MT, Ta VT, Nguyen LD, Phan L, Han KQ, Duong TH, Tran NB, Wills B, Wolbers M, Simmons CP. An Evidence-Based Algorithm for Early Prognosis of Severe Dengue in the Outpatient Setting. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64:656-663. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Djossou F, Vesin G, Elenga N, Demar M, Epelboin L, Walter G, Abboud P, Le-Guen T, Rousset D, Moreau B, Mahamat A, Malvy D, Nacher M. A predictive score for hypotension in patients with confirmed dengue fever in Cayenne Hospital, French Guiana. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2016;110:705-713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Suwarto S, Nainggolan L, Sinto R, Effendi B, Ibrahim E, Suryamin M, Sasmono RT. Dengue score: a proposed diagnostic predictor for pleural effusion and/or ascites in adults with dengue infection. BMC Infect Dis. 2016;16:322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lam PK, Tam DT, Dung NM, Tien NT, Kieu NT, Simmons C, Farrar J, Wills B, Wolbers M. A Prognostic Model for Development of Profound Shock among Children Presenting with Dengue Shock Syndrome. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0126134. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Leo YS, Gan VC, Ng EL, Hao Y, Ng LC, Pok KY, Dimatatac F, Go CJ, Lye DC. Utility of warning signs in guiding admission and predicting severe disease in adult dengue. BMC Infect Dis. 2013;13:498. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Diaz-Quijano FA, Villar-Centeno LA, Martinez-Vega RA. Predictors of spontaneous bleeding in patients with acute febrile syndrome from a dengue endemic area. J Clin Virol. 2010;49:11-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Potts JA, Gibbons RV, Rothman AL, Srikiatkhachorn A, Thomas SJ, Supradish PO, Lemon SC, Libraty DH, Green S, Kalayanarooj S. Prediction of dengue disease severity among pediatric Thai patients using early clinical laboratory indicators. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4:e769. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 80] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Srisuphanunt M, Puttaruk P, Kooltheat N, Katzenmeier G, Wilairatana P. Prognostic Indicators for the Early Prediction of Severe Dengue Infection: A Retrospective Study in a University Hospital in Thailand. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2022;7:162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Marois I, Forfait C, Inizan C, Klement-Frutos E, Valiame A, Aubert D, Gourinat AC, Laumond S, Barsac E, Grangeon JP, Cazorla C, Merlet A, Tarantola A, Dupont-Rouzeyrol M, Descloux E. Development of a bedside score to predict dengue severity. BMC Infect Dis. 2021;21:470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Devarbhavi H, Ganga D, Menon M, Kothari K, Singh R. Dengue hepatitis with acute liver failure: Clinical, biochemical, histopathological characteristics and predictors of outcome. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;35:1223-1228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Tangnararatchakit K, Chuansumrit A, Watcharakuldilok P, Apiwattanakul N, Lertbunrian R, Keatkla J, Yoksan S. Daily Dengue Severity Score to Assess Severe Manifestations. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2020;39:184-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Lee IK, Huang CH, Huang WC, Chen YC, Tsai CY, Chang K, Chen YH. Prognostic Factors in Adult Patients with Dengue: Developing Risk Scoring Models and Emphasizing Factors Associated with Death ≤7 Days after Illness Onset and ≤3 Days after Presentation. J Clin Med. 2018;7:396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Phakhounthong K, Chaovalit P, Jittamala P, Blacksell SD, Carter MJ, Turner P, Chheng K, Sona S, Kumar V, Day NPJ, White LJ, Pan-Ngum W. Predicting the severity of dengue fever in children on admission based on clinical features and laboratory indicators: application of classification tree analysis. BMC Pediatr. 2018;18:109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Md-Sani SS, Md-Noor J, Han WH, Gan SP, Rani NS, Tan HL, Rathakrishnan K, A-Shariffuddin MA, Abd-Rahman M. Prediction of mortality in severe dengue cases. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18:232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Suwarto S, Hidayat MJ, Widjaya B. Dengue score as a diagnostic predictor for pleural effusion and/or ascites: external validation and clinical application. BMC Infect Dis. 2018;18:90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Fernández E, Smieja M, Walter SD, Loeb M. A retrospective cohort study to predict severe dengue in Honduran patients. BMC Infect Dis. 2017;17:676. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Lee IK, Liu JW, Chen YH, Chen YC, Tsai CY, Huang SY, Lin CY, Huang CH. Development of a Simple Clinical Risk Score for Early Prediction of Severe Dengue in Adult Patients. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0154772. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Pongpan S, Patumanond J, Wisitwong A, Tawichasri C, Namwongprom S. Validation of dengue infection severity score. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2014;7:45-49. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Pongpan S, Wisitwong A, Tawichasri C, Patumanond J, Namwongprom S. Development of dengue infection severity score. ISRN Pediatr. 2013;2013:845876. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Huang CC, Hsu CC, Guo HR, Su SB, Lin HJ. Dengue fever mortality score: A novel decision rule to predict death from dengue fever. J Infect. 2017;75:532-540. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Pang J, Thein TL, Leo YS, Lye DC. Early clinical and laboratory risk factors of intensive care unit requirement during 2004-2008 dengue epidemics in Singapore: a matched case-control study. BMC Infect Dis. 2014;14:649. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Yang J, Mosabbir AA, Raheem E, Hu W, Hossain MS. Demographic characteristics, clinical symptoms, biochemical markers and probability of occurrence of severe dengue: A multicenter hospital-based study in Bangladesh. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2023;17:e0011161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Chi CY, Sung TC, Chang K, Chien YW, Hsu HC, Tu YF, Huang YT, Shih HI. Development and Utility of Practical Indicators of Critical Outcomes in Dengue Patients Presenting to Hospital: A Retrospective Cross-Sectional Study. Trop Med Infect Dis. 2023;8:188. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Alam R, Fathema K, Yasmin A, Roy U, Hossen K, Rukunuzzaman M. Prediction of severity of dengue infection in children based on hepatic involvement. JGH Open. 2024;8:e13049. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Ananda Rao A, U RR, Gosavi S, Menon S. Dengue Fever: Prognostic Insights From a Complete Blood Count. Cureus. 2020;12:e11594. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Martínez-Cuellar C, Lovera D, Galeano F, Gatti L, Arbo A. Non-structural protein 1 (NS1) of dengue virus detection correlates with severity in primary but not in secondary dengue infection. J Clin Virol. 2020;124:104259. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Belletti A, Lerose CC, Zangrillo A, Landoni G. Vasoactive-Inotropic Score: Evolution, Clinical Utility, and Pitfalls. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2021;35:3067-3077. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Article Influence: 38.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Baysal PK, Güzelmeriç F, Kahraman E, Gürcü ME, Erkılınç A, Orki T. Is Vasoactive-Inotropic Score a Predictor for Mortality and Morbidity in Patients Undergoing Coronary Artery Bypass Surgery? Braz J Cardiovasc Surg. 2021;36:802-806. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Sandrio S, Krebs J, Leonardy E, Thiel M, Schoettler JJ. Vasoactive Inotropic Score as a Prognostic Factor during (Cardio-) Respiratory ECMO. J Clin Med. 2022;11:2390. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Song J, Cho H, Park DW, Moon S, Kim JY, Ahn S, Lee SG, Park J. Vasoactive-Inotropic Score as an Early Predictor of Mortality in Adult Patients with Sepsis. J Clin Med. 2021;10:495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Alshiakh SM. Role of serum lactate as prognostic marker of mortality among emergency department patients with multiple conditions: A systematic review. SAGE Open Med. 2023;11:20503121221136401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Loomba RS, Farias JS, Villarreal EG, Flores S. Serum Lactate and Mortality during Pediatric Admissions: Is 2 Really the Magic Number? J Pediatr Intensive Care. 2022;11:83-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Rathee K, Dhull V, Dhull R, Singh S. Biosensors based on electrochemical lactate detection: A comprehensive review. Biochem Biophys Rep. 2016;5:35-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 10.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Barniol J, Gaczkowski R, Barbato EV, da Cunha RV, Salgado D, Martínez E, Segarra CS, Pleites Sandoval EB, Mishra A, Laksono IS, Lum LC, Martínez JG, Núnez A, Balsameda A, Allende I, Ramírez G, Dimaano E, Thomacheck K, Akbar NA, Ooi EE, Villegas E, Hien TT, Farrar J, Horstick O, Kroeger A, Jaenisch T. Usefulness and applicability of the revised dengue case classification by disease: multi-centre study in 18 countries. BMC Infect Dis. 2011;11:106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 8.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Annan E, Treviño J, Zhao B, Rodriguez-Morales AJ, Haque U. Direct and indirect effects of age on dengue severity: The mediating role of secondary infection. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2023;17:e0011537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Guzman MG, Alvarez M, Halstead SB. Secondary infection as a risk factor for dengue hemorrhagic fever/dengue shock syndrome: an historical perspective and role of antibody-dependent enhancement of infection. Arch Virol. 2013;158:1445-1459. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 444] [Cited by in RCA: 538] [Article Influence: 41.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Marchiori E, Ferreira JL, Bittencourt CN, de Araújo Neto CA, Zanetti G, Mano CM, Santos AA, Vianna AD. Pulmonary hemorrhage syndrome associated with dengue fever, high-resolution computed tomography findings: a case report. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2009;4:8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Keshav LB, K A, Malhotra K, Shetty S. Lung Manifestation of Dengue Fever: A Retrospective Study. Cureus. 2024;16:e60655. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Yong YK, Wong WF, Vignesh R, Chattopadhyay I, Velu V, Tan HY, Zhang Y, Larsson M, Shankar EM. Dengue Infection - Recent Advances in Disease Pathogenesis in the Era of COVID-19. Front Immunol. 2022;13:889196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Low GK, Jiee SF, Masilamani R, Shanmuganathan S, Rai P, Manda M, Omosumwen OF, Kagize J, Gavino AI, Azahar A, Jabbar MA. Routine blood parameters of dengue infected children and adults. A meta-analysis. Pathog Glob Health. 2023;117:565-589. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Nelson ER, Chulajata R. Danger signs in Thai hemorrhagic fever (dengue). J Pediatr. 1965;67:463-470. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Tsai CJ, Kuo CH, Chen PC, Changcheng CS. Upper gastrointestinal bleeding in dengue fever. Am J Gastroenterol. 1991;86:33-35. [PubMed] |

| 58. | Chua CLL, Morales RF, Chia PY, Yeo TW, Teo A. Neutrophils - an understudied bystander in dengue? Trends Microbiol. 2024;32:1132-1142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Kalluru PKR, Mamilla M, Valisekka SS, Mandyam S, Calderon Martinez E, Posani S, Sharma S, Gopavaram RR, Gargi B, Gaddam A, Reddy S. Aminotransferases in Relation to the Severity of Dengue: A Systematic Review. Cureus. 2023;15:e39436. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Cornesky RA, Hammon WM, Atchison RW, Sather GE. Effect of urea on the hemagglutinating and complement-fixing antigens of type 2 Dengue virus. Infect Immun. 1972;6:952-957. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Ali SAAM, Gibreel MOA, Suliman NSEKB, Mohammed AKA, Nour BYM. Prediction of Acute Renal Failure in Dengue Fever Patients. Open J Urol. 2022;12:99-106. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 62. | Tsheten T, Clements ACA, Gray DJ, Adhikary RK, Furuya-Kanamori L, Wangdi K. Clinical predictors of severe dengue: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Infect Dis Poverty. 2021;10:123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 18.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Moallemi S, Lloyd AR, Rodrigo C. Early biomarkers for prediction of severe manifestations of dengue fever: a systematic review and a meta-analysis. Sci Rep. 2023;13:17485. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Dijkland SA, Retel Helmrich IRA, Steyerberg EW. Validation of prognostic models: challenges and opportunities. J Emerg Crit Care Med. 2018;2:91-91. [DOI] [Full Text] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/