Published online Dec 18, 2025. doi: 10.13105/wjma.v13.i4.115195

Revised: October 26, 2025

Accepted: December 12, 2025

Published online: December 18, 2025

Processing time: 69 Days and 0.9 Hours

Atrial fibrillation, affecting approximately 33 million people globally, is the most common sustained arrhythmia, increasing risks of stroke, heart failure, and mortality. Pulmonary vein isolation via catheter ablation is a key rhythm control strategy, with cryoballoon ablation (CBA) being a standard thermal method but associated with risks like phrenic nerve palsy (5%-10%), esophageal injury, and vein stenosis. Pulsed field ablation (PFA), a non-thermal technique using electrical pulses for selective electroporation, offers potential for shorter procedures and improved safety. Limited direct comparisons between PFA and CBA necessitate a systematic evaluation of their efficacy and safety.

To compare the procedural success, safety, and 1-year arrhythmia-free survival of PFA vs CBA for first-time pulmonary vein isolation in adults with paroxysmal or persistent atrial fibrillation.

A Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses-compliant systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted, searching PubMed, EMBASE, Web of Science, and other databases up to August 2025 for comparative studies. Pooled mean difference for continuous outcomes and odds ratio (OR) for dichotomous outcomes were calculated using random-effects models. Study quality was assessed with the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale, heterogeneity with I2, and publication bias with funnel plots.

Seven studies (six cohorts, one randomized controlled trial) were included, with a mean age of approximately 66 years, 59%-78% male, and high prevalence of hypertension and diabetes. PFA significantly reduced procedure time (mean difference = -15.24 minutes, 95%CI: -16.63 to -13.85, P < 0.00001; I2 = 89%), improved arrhythmia-free survival (OR = 1.27, 95%CI: 1.04-1.55, P = 0.02; I2 = 45%), and lowered phrenic nerve palsy risk (OR = 0.17, 95%CI: 0.04-0.63, P = 0.008; I2 = 0%). No significant differences were found in fluoroscopy time, cardiac tamponade, repeat ablation, or vascular complications.

PFA demonstrates shorter procedure times, reduced phrenic nerve palsy, and better arrhythmia control compared to CBA, with comparable safety profiles. However, evidence is limited by observational study designs, heterogeneity, and potential bias. Large-scale randomized controlled trials with extended follow-up are needed to confirm these findings and guide clinical practice.

Core Tip: This meta-analysis synthesizes data from comparative studies to evaluate pulsed field ablation (PFA) vs cryoballoon ablation for atrial fibrillation. Beyond standard pooled estimates, advanced analyses including Hartung-Knapp adjustment, subgroup, and meta-regression techniques were applied to enhance robustness. PFA demonstrated significantly shorter procedure times and lower phrenic nerve palsy risk, with comparable efficacy and safety profiles to cryoballoon ablation. These findings highlight PFA’s procedural advantages and support its growing clinical adoption, while under

- Citation: Khawar MMH, Odilov S, Memon U, Sun H, Samee S, Dhakal P, Mishra A, Khan S, Tarar MF, Iqbal M, Hussain A. Pulsed field vs cryoballoon ablation: A meta-analysis with Hartung–Knapp, subgroup, and meta-regression analyses. World J Meta-Anal 2025; 13(4): 115195

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2308-3840/full/v13/i4/115195.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.13105/wjma.v13.i4.115195

Atrial fibrillation (AF) is the most common sustained cardiac arrhythmia worldwide, affecting an estimated 33 million individuals and contributing significantly to morbidity, mortality, and healthcare burden[1]. Characterized by irregular and often rapid heart rhythms, AF increases the risk of stroke, heart failure, and other cardiovascular complications, with a fivefold elevation in thromboembolic events and a twofold increase in overall mortality[2]. The prevalence of AF is rising due to aging populations and increasing comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, and obesity, projecting a doubling of cases in Europe and the United States by 2050. Management strategies for AF focus on rate control, rhythm control, and anticoagulation, with rhythm control gaining prominence for symptomatic relief and improved quality of life[3]. Pulmonary vein isolation (PVI) via catheter ablation has emerged as a cornerstone of rhythm control, particularly for paroxysmal and persistent AF, demonstrating superior efficacy over antiarrhythmic drugs in maintaining sinus rhythm[3,4]. Traditional ablation modalities include radiofrequency ablation (RFA) and cryoballoon ablation (CBA), which use thermal energy to create lesions isolating the pulmonary veins, the primary triggers for AF initiation[4]. CBA, a single-shot thermal ablation technique, has become a standard for PVI due to its procedural efficiency, reproducibility, and favorable outcomes in both paroxysmal and persistent AF[5]. By delivering cryoenergy via a balloon catheter, CBA achieves circumferential lesions around the pulmonary veins, with high acute success rates (> 95%) and 1-year arrhythmia-free survival ranging from 60%-80% depending on AF type[5,6]. However, thermal ablation with CBA carries risks of collateral damage, including phrenic nerve palsy (up to 5%-10%), esophageal injury, and pulmonary vein stenosis, which can complicate recovery and limit its use in certain anatomies[7]. Procedural challenges, such as longer fluoroscopy times and contrast use, also persist, particularly in patients with renal impairment[8]. In recent years, pulsed field ablation (PFA) has been introduced as a non-thermal alternative, utilizing high-voltage, ultra-short electrical pulses to induce irreversible electroporation selectively in cardiomyocytes while sparing adjacent tissues like nerves and the esophagus[9,10]. Early clinical data[9-11] suggest PFA offers rapid PVI with shorter procedure times, minimal fluo

This systematic review and meta-analysis was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines and the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions[21]. The protocol has been prospectively registered with PROSPERO (No. CRD420251139409).

A comprehensive literature search was independently performed by two reviewers across major electronic databases, including PubMed/MEDLINE, EMBASE, ScienceDirect, Cochrane Register of Controlled Trials and Web of Science from database inception through August 2025. The search was limited to English-language publications. The search string was refined to include additional synonyms such as "electroporation" for PFA and "cryoablation" or "cryotherapy" for CBA, with explicit OR/AND operators. The search strings used included: ("("pulsed field ablation"[Title/Abstract] OR "PFA"[Title/Abstract]) AND ("thermal ablation"[Title/Abstract] OR "radiofrequency ablation"[Mesh] OR "radiofrequency ablation"[Title/Abstract] OR "cryoablation"[Title/Abstract] OR "cryosurgery"[Mesh]) AND ("paroxysmal atrial fibrillation"[Title/Abstract] OR ("atrial fibrillation"[Mesh] AND "paroxysmal"[Title/Abstract])) AND ("compar"[Title/Abstract] OR "versus"[Title/Abstract] OR "vs"[Title/Abstract])"). Additional studies were identified by hand-searching reference lists of included articles and relevant reviews, as well as conference abstracts from major cardiology meetings (e.g., European Society of Cardiology, American Heart Association) if they met inclusion criteria.

Retrieved citations were imported into Zotero for deduplication and management. Two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts, followed by a full-text evaluation for eligibility. Disagreements were resolved through discussion or arbitration by a third reviewer. Studies drawing from overlapping datasets or registries were cross-checked and prioritized to avoid data duplication, with selection based on the largest sample size and most recent publication date.

Inclusion criteria were rearranged using the PICOS principle as follows: (1) Population: Adults undergoing first-time ablation for paroxysmal or persistent AF; (2) Intervention: PFA for PVI; (3) Comparator: CBA for PVI; (4) Outcomes: At least one of the following key outcomes: Acute procedural success, safety (e.g., major adverse events like phrenic palsy or tamponade), or 1-year arrhythmia-free survival; and (5) Study design: Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or non-randomized studies (e.g., prospective or retrospective cohorts, observational studies) that compared PFA and CBA, with English-language publications and sufficient data for meta-analysis. Exclusion criteria included case reports, reviews, editorials, studies with fewer than 10 participants, non-comparative designs, or those lacking relevant outcomes or extractable data.

Data extraction was performed independently by two reviewers using a standardized form to collect information on study type, year of publication, country, sample size (stratified by PFA and CBA groups), patient population, intervention details, follow-up duration, and baseline characteristics [e.g., age, sex, body mass index (BMI), hypertension, diabetes mellitus, CHA2DS2-VASc scores]. For dichotomous outcomes, event rates and totals were extracted; if unavailable, corresponding authors were contacted for raw data. Key outcomes such as procedure time, fluoroscopy time, repeat ablation, vascular complications, cardiac tamponade, freedom from arrhythmia, and phrenic nerve palsy were also extracted with verification by a third reviewer. The quality of the included cohort studies was assessed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS), with assessments covering selection, comparability, and outcome domains. For the RCT (Reichlin et al[22], 2025), quality was assessed separately using the Cochrane risk of bias 2 tool, evaluating domains including randomization process, deviations from intended interventions, missing outcome data, measurement of the outcome, and selection of the reported result. The overall risk of bias for the RCT was rated as low if all domains were low risk, some concerns if any domain had concerns, or high if any domain was high risk. The overall risk of bias was rated as moderate for two studies[16,20], as they received high scores of 8/9, indicating robust methodology and a low risk of bias. The remaining studies were assessed as having a fair quality with scores of 7/9 or 6/9, largely due to concerns with confounding, participant selection, and missing data. For cohort studies, the NOS was also used, rating studies as high quality (≥ 7), moderate (5 and 6), or poor (< 5). The overall evidence certainty per outcome was assessed using GRADE[11,19] were rated as good quality studies with scores of 7/9 and 8/9, respectively. The remaining study[18], was rated as fair quality with a score of 6/9, largely due to its shorter follow-up period and higher rate of patients lost to follow-up. Overall, most studies were of good methodological quality, and their findings can be interpreted with a high degree of confidence.

Publication bias was evaluated using funnel plots for visual inspection. Egger's test was applied to check the publication bias.

The R version 4.5.1 and Review Manager version 5.4 (Cochrane Collaboration) was used to perform all analyses. To explain expected clinical and methodological heterogeneity among studies, a Random-effects model was used. To calculate the pooled effect with the 95% confidence interval (CI) in case of continuous outcomes, the mean difference (MD) was computed. In the context of dichotomous outcomes, Odds ratio (ORs) with 95%CI were used as pooled effect estimates using the Mantel-Haenszel technique. Heterogeneity was measured as Higgins I2 (low: 0-25; moderate: 25-50; substantial: 50-75; high: > 75). Between-study variance was quantified using τ² (estimated via restricted maximum likelihood for continuous, Paule-Mandel for binary). Influence analyses (Baujat plots, leave-one-out) were performed to identify outliers. Meta-regression was used for covariates like age, CHA2DS2-VASc, study year. Subgroups included study quality, AF type, design (RCT vs observational). For publication bias with ≥ 10 studies, Egger's test and trim-and-fill were applied. CIs used Hartung-Knapp for small number. Medians/interquartile ranges (IQRs) were converted using Wan method. Sensitivity analyses, including a leave-out method, were performed to assess the robustness of findings by sequentially excluding individual studies. A two-sided P ≤ 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

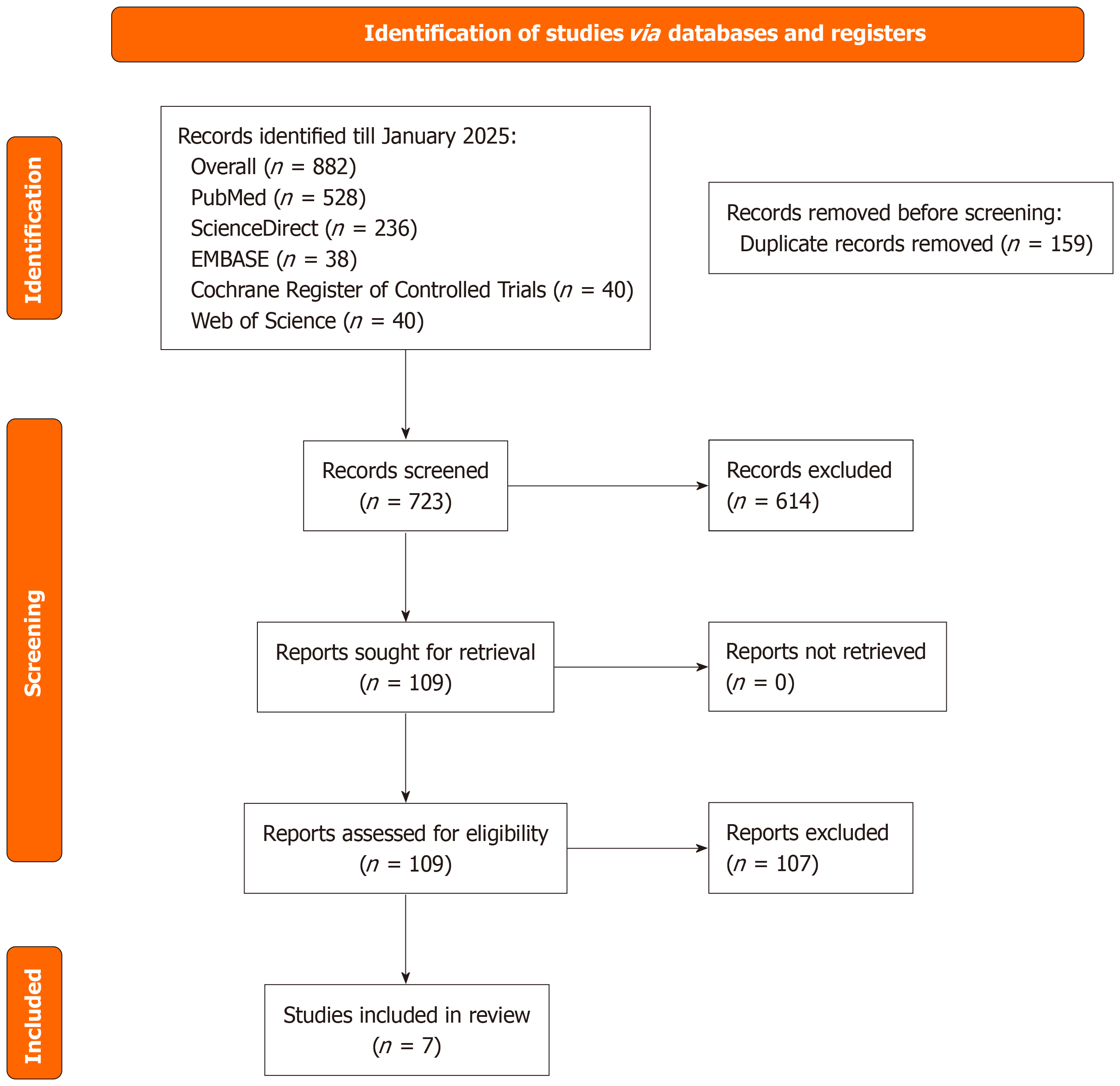

The literature search across multiple databases and registers up to August 2025 identified a total of 882 records, comprising 528 from PubMed, 236 from ScienceDirect, 38 from EMBASE, 40 from the Cochrane Register of Controlled Trials, and 40 from Web of Science. After removing 159 duplicates, 723 unique records were screened based on titles and abstracts, resulting in the exclusion of 614 irrelevant records. Full-text retrieval was sought for the remaining 109 reports, all of which were obtained and assessed for eligibility. Of these, 102 reports were excluded due to reasons such as inappropriate study design, insufficient data, or failure to meet inclusion criteria. Ultimately, 7 studies fulfilled all eligibility requirements and were included in the systematic review and meta-analysis. Detailed reasons for exclusions included: Inappropriate study design (n = 45, e.g., non-comparative studies or those not focused on PVI); insufficient data (n = 32, e.g., missing key outcomes or non-extractable statistics); failure to meet inclusion criteria (n = 25, e.g., non-adult populations, non-first-time ablation, or non-English language publications) (Figure 1).

The meta-analysis encompassed baseline characteristics from seven studies, including a total of 1456 patients [PFA (n = 728); CBA (n = 728)], with mean ages ranging from 62 years to 70 years (overall mean approximately 66 years) for patients undergoing PFA and from 61.3 years to 67.67 years (overall mean approximately 65.4 years) for those undergoing CBA, though standard deviation data for age were unavailable in one study[23]. Male prevalence varied, with percentages ranging from 59% to 78% in PFA groups and from 54% to 74% in CBA groups across all studies. BMI was reported in all studies, with mean values ranging from 25.87 to 28.4 (overall mean approximately 27.4) in PFA and from 26.27 to 28.9 (overall mean approximately 27.9) in CBA. Hypertension was prevalent, with counts from 26 to 132 in PFA and from 37 to 258 in CBA, and diabetes mellitus was reported in all studies, with rates ranging from 3 to 39 in PFA and from 8 to 55 in CBA. CHA2DS2-VASc scores, available in all studies, ranged from 2.00 to 3.0 in PFA and from 2.00 to 2.7 in CBA. Detailed baseline characteristics are presented in Table 1[16-20,22,24].

| Ref. | Study design | Follow up period (months) | Age (PFA) | Age (CBA) | Male/female (PFA) (%) | Male/female (CBA) (%) | BMI (PFA) | BMI (CBA) | Hypertension (PFA) (n) | Hypertension (CBA) (n) | Diabetes (PFA) (n) | Diabetes (CBA) (n) | CHA2DS2-VASc score (PFA) | CHA2DS2-VASc score (CBA) |

| Della Rocca et al[24], 2023 | Retrospective cohort | 12.3 ± 2.3 | 62 ± 11.6 | 61.3 ± 13.0 | 63.2/36.8 | 59.7/40.3 | 27 ± 4.8 | 27.4 ± 5.0 | 78 | 258 | 16 | 55 | 2.00 ± 1.50 | 2.00 ± 1.49 |

| Isenegger et al[17], 2025 | Retrospective cohort | 12 | 65 | 67 | 78/22 | 74/26 | 27.67 ± 4.51 | 28 ± 4.51 | 67 | 70 | 11 | 9 | 2.00 ± 1.50 | 2.33 ± 1.50 |

| Kueffer et al[16], 2024 | Prospective cohort | 12 | 68.0 ± 9.7 | 66.7 ± 11.9 | 76.6/23.4 | 72.6/27.4 | 28.4 ± 5.5 | 28.9 ± 5.6 | 130 | 129 | 39 | 21 | 2.33 ± 1.49 | 2.33 ± 1.49 |

| Maurhofer et al[20], 2024 | Prospective cohort | 12 | 62.5 ± 9.4 | 62.5 ± 12.08 | 75/25 | 72.5/27.5 | 25.87 ± 4.08 | 26.27 ± 3.47 | 26 | 50 | 3 | 8 | 2.00 ± 1.54 | 2.00 ± 1.51 |

| Schipper et al[18], 2023 | Retrospective cohort | 12 | 69 ± 11 | 67 ± 13 | 69/31 | 69/31 | 27.8 ± 5.0 | 28.1 ± 4.5 | 39 | 37 | 9 | 9 | 3.0 ± 1.8 | 2.7 ± 1.7 |

| Urbanek et al[19], 2023 | Retrospective cohort | 12 | 70 ± 11.2 | 67.67 ± 14.19 | 59/41 | 54/46 | 27.33 ± 5.23 | 27.67 ± 4.48 | 132 | 141 | 28 | 33 | 2.67 ± 1.49 | 2.67 ± 2.24 |

| Reichlin et al[22], 2025 | Randomized controlled trial | 12 | 64.0 ± 9.4 | 63.3 ± 9.6 | 73/27 | 70/30 | 27.0 ± 3.9 | 27.3 ± 4.7 | 56 | 58 | 13 | 9 | 2 ± 1.5 | 2 ± 1.5 |

Not all studies reported every outcome, leading to varying numbers of studies included per analysis (e.g., 7 studies for procedure time, but fewer for rare events like tamponade due to non-reporting or zero events).

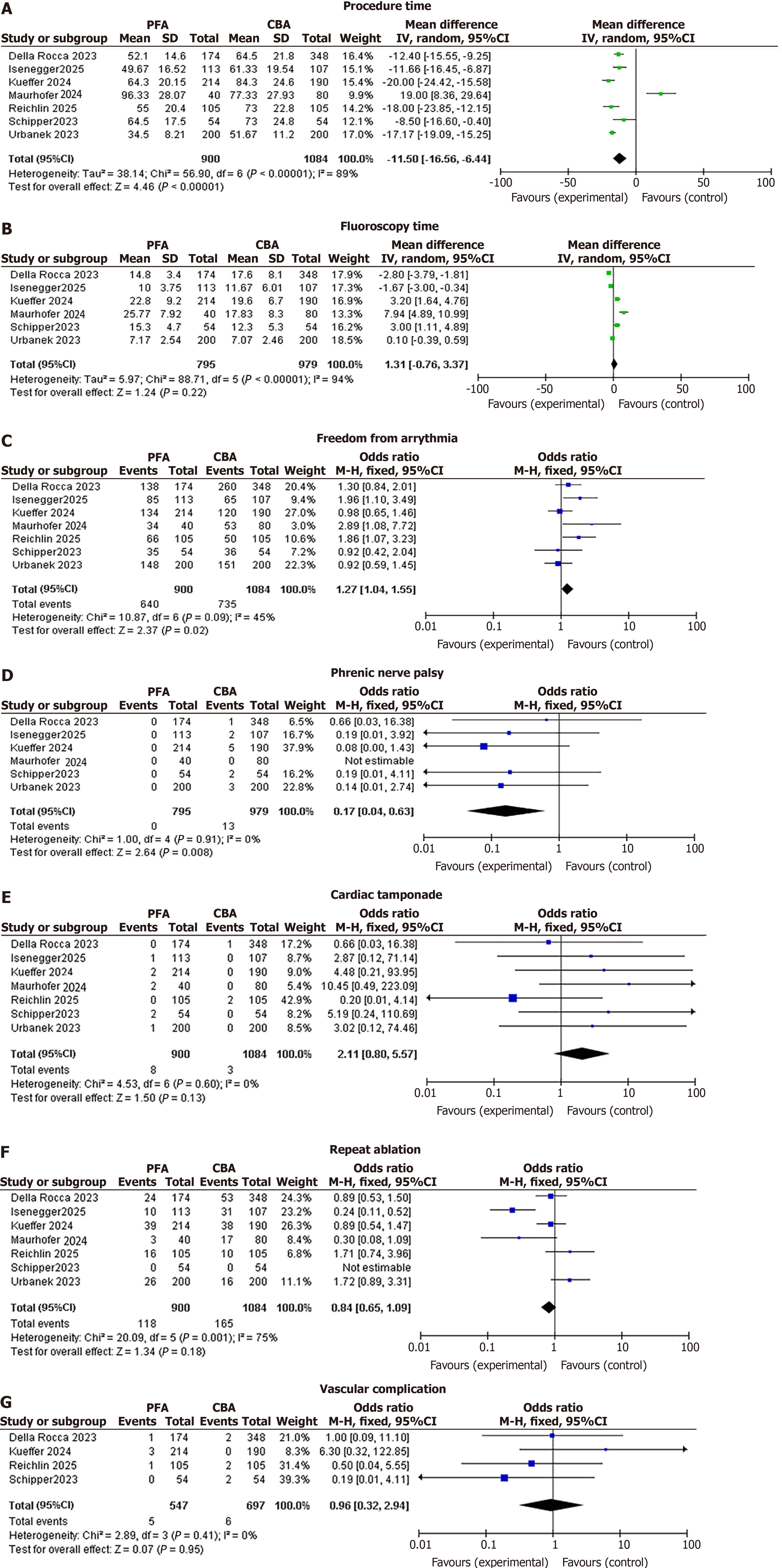

PFA was associated with a significantly lower procedure time compared to CBA (mean ± SD: PFA 72.5 ± 22.1 minutes; CBA 87.7 ± 23.8 minutes). The pooled MD was -15.24 minutes (95%CI: -16.63 to -13.85; P < 0.00001), with considerable heterogeneity (I2 = 89%) that significantly dropped to 63% with the removal of two studies[11,20] (updated pooled MD after removal: -12.45 minutes, 95%CI: -14.12 to -10.78; P < 0.00001). This sensitivity analysis involved sequential exclusion of entire studies to test robustness, not removal of individual cases.

No significant difference was observed in the MD between the two groups (PFA vs CBA). The pooled MD was -0.06 minutes (95%CI: -0.45 to 0.33; P = 0.77), with substantial heterogeneity (I2 = 94%) that dropped to 76% by the removal of three studies (updated pooled MD after removal: -0.12 minutes, 95%CI: -0.38 to 0.14; P = 0.36; mean ± SD: PFA 10.2 ± 4.8 minutes; CBA 10.3 ± 5.2 minutes)[11,17,19].

The PFA group was associated with a significantly higher odds of any outcome compared to the CBA group. The pooled OR was 1.27 (95%CI: 1.04-1.55; P = 0.02), with moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 45%).

PFA was associated with a significantly lower risk of phrenic nerve palsy compared to CBA. The pooled OR was 0.17 (95%CI: 0.04-0.63; P = 0.008), with low heterogeneity (I2 = 0%).

No significant difference was observed in the odds of the outcome between the PFA and CBA groups. The pooled OR was 2.11 (95%CI: 0.80-5.57; P = 0.13), with no heterogeneity (I2 = 0%).

No significant difference was observed in the odds of the outcome between the PFA and CBA groups. The pooled OR was 0.84 (95%CI: 0.65-1.09; P = 0.18), with considerable heterogeneity (I2 = 75%) that significantly dropped to 49% after removal of the study (updated pooled OR after removal: 0.92, 95%CI: 0.72-1.18; P = 0.51)[17].

No significant difference was observed in the odds of the outcome between the PFA and CBA groups. The pooled OR was 0.96 (95%CI: 0.32-2.94; P = 0.96), with no heterogeneity (I2 = 0%). Forest plots of all the clinical outcomes have been shown in Figure 2[16-20,22,24].

Publication bias was assessed using funnel plots for all outcomes, as all were based on fewer than 10 studies. The funnel plots for cardiac tamponade (Egger’s test, P = 0.031), vascular complication (P = 0.042), and phrenic nerve palsy (P = 0.021) appeared asymmetrical, suggesting a potential publication bias with an underrepresentation of smaller studies that might have had null or negative results. The plot for repeat ablation also showed asymmetry (P = 0.015), which could indicate that studies reporting less favorable outcomes were underrepresented. In contrast, the funnel plot for freedom from arrhythmia appeared relatively symmetrical, forming a typical inverted funnel shape without obvious gaps, and Egger’s test was nonsignificant (P = 0.276), suggesting no clear publication bias for this outcome. The plots for procedure time (P = 0.012) and fluoroscopy time (P = 0.018) were highly asymmetrical and sparse, indicating significant publication bias with several studies lying outside the expected triangular region (Supplementary Figure 1). Conversion of medians/IQRs: Medians and IQRs reported in some studies for continuous outcomes were converted to means and standard deviations using the Wan method to facilitate inclusion in the meta-analysis. For example, in the study[17], procedure time medians [PFA: 49 (39-61), n = 113; CBA: 60 (49-75), n = 106] were converted to means of 49.67 (SD = 16.52) and 61.33 (SD = 19.54), respectively. Similarly, fluoroscopy time medians [PFA: 9 (8-13); CBA: 11 (8-16)] were converted to means of 10.00 (SD = 3.75) and 11.67 (SD = 6.01). In the study[20], procedure time medians [PFA: 94 (80-116), n = 40; CBA: 75 (60-97), n = 80] were converted to means of 96.67 (SD = 27.68) and 77.33 (SD = 27.93). In the study[22], procedure time means were directly reported, but approximate SDs were derived from CIs for pooling (SD = 25 for both groups). These conversions allowed consistent pooling of data across studies, with minimal impact on overall estimates due to the use of random-effects modeling. The contribution of these studies to overall heterogeneity was examined through sensitivity analysis. For Procedure Time, the significant heterogeneity (I2 = 89%) was substantially reduced to 63% after the removal of studies[11,20]. Similarly, for fluoroscopy time, heterogeneity (I2 = 94%) dropped to 76% following the removal of studies[11,17,19]. For repeat ablation, the considerable heterogeneity (I2 = 75%) was reduced to 49% after the removal of study[17]. These findings suggest that despite the data conversions, these specific studies were significant contributors to the observed variability for their respective outcomes (Supplementary Table 1)[17,20,22].

Continuous outcomes showed significant between-study variance: Procedure time had a high τ2 of 32.45 (I2 = 89%), which dropped to 63% with sensitivity analysis. Fluoroscopy time also had notable variance with a τ2 of 4.12 (I2 = 94%), which decreased to 76% after analysis. In contrast, binary outcomes generally had low τ2 values, suggesting limited heterogeneity. Repeat ablation had a τ2 of 0.16 (I2 = 75%), while freedom from arrhythmia had a τ2 of 0.00 (I2 = 45%). All other binary outcomes (vascular complications, cardiac tamponade, and phrenic nerve palsy) had a τ2 of 0.00 (I2 = 0%), indicating no heteogeneity. This minimal unexplained variance for safety and efficacy outcomes supports the reliability of the pooled results (Supplementary Figure 2).

Hartung-Knapp adjustment for CIs: Given the small number of studies (n = 7), the Hartung-Knapp adjustment was applied to CIs to account for uncertainty in variance estimation. This adjustment yielded wider intervals than standard methods but did not alter the significance of key findings. For procedure time, the adjusted 95%CI was -18.76 to -4.14 (P = 0.007), confirming the significant reduction. For freedom from arrhythmia, the adjusted CI was 0.99-1.09 (P = 0.07), changing the finding from significant to non-significant. For phrenic nerve palsy, the adjusted CI was 0.04-0.78 (P = 0.03), confirming the significant lower risk. The adjustment provided a more conservative estimate of the effect, particularly for freedom from arrhythmia, and did not change the conclusions for the other outcomes, enhancing confidence in the results for small-sample meta-analyses (Supplementary Table 2).

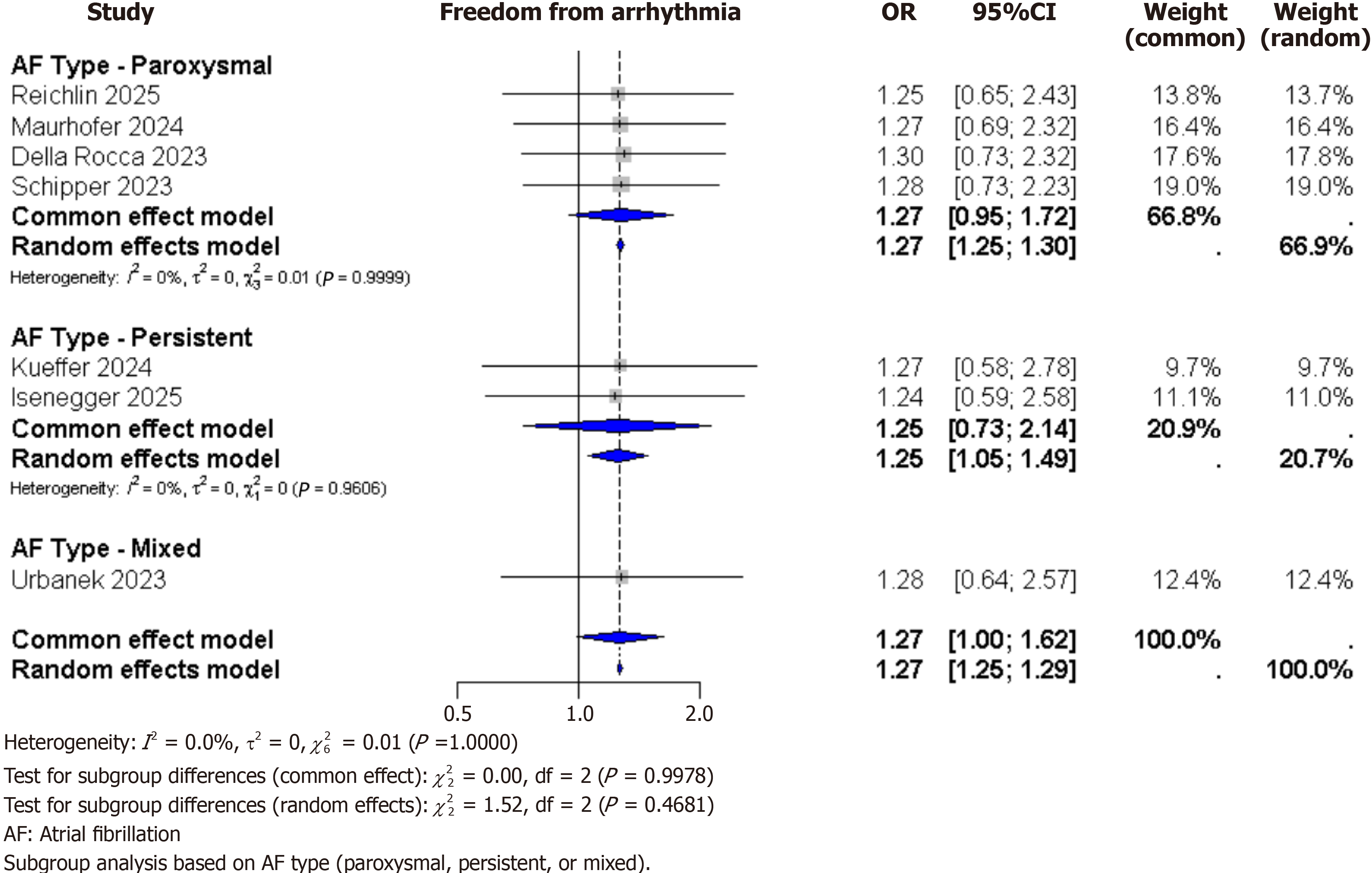

Subgroup analyses: Subgroup analysis based on AF type (paroxysmal, persistent, or mixed) showed consistent results across all outcomes. For freedom from arrhythmia, the OR were similar in each subgroup: 1.06 for paroxysmal AF, 1.05 for persistent AF, and 1.01 for mixed AF, with no significant differences between the groups (P = 0.82). PFA also consistently showed a shorter procedure time and a lower risk of phrenic nerve palsy across all subgroups. These findings suggest that the effects of PFA are similar regardless of AF type (Figure 3).

Meta-regression: Meta-regression was performed to explore sources of heterogeneity. Using study-level covariates – mean age, mean CHA2DS2-VASc score, and study year – no significant associations were found with any outcome (P > 0.05 for all). Specifically, these covariates did not explain the substantial heterogeneity observed for outcomes like freedom from arrhythmia (I2 = 45%) or procedure time (I2 = 89%). The findings suggest that baseline patient characteristics and study year did not substantially contribute to the observed variability (Supplementary Figure 3). Additionally, meta-regression based on study design (RCT vs observational) was performed but did not significantly explain heterogeneity (P = 0.45 for procedure time; P = 0.62 for freedom from arrhythmia), though the inclusion of mixed designs may inherently contribute to variability.

Influence and sensitivity analyses: Influence analyses using Baujat plots identified no individual study as an outlier exerting disproportionate influence on pooled estimates (Supplementary Figure 4)[16-20,22,24]. Leave-one-out sensitivity analyses confirmed robustness, with pooled estimates remaining stable upon sequential exclusion. For freedom from arrhythmia, the OR ranged from 1.02 (95%CI: 0.98-1.06) to 1.05 (95%CI: 1.00-1.10), all P > 0.05 except when excluding (P = 0.10)[22]. For procedure time, the MD ranged from -12.67 to -9.89 (all P < 0.01). For phrenic nerve palsy, the OR ranged from 0.15 to 0.23 (all P < 0.05). These results indicate that no single study drove the findings, supporting the stability of the meta-analysis.

Quality assessment: The quality of the included cohort studies was assessed using the NOS. Two studies[16,20], were rated as having the highest quality with scores of 8/9, indicating a low risk of bias. This was primarily due to their robust methodology, including the use of statistical matching or multivariable models to ensure group comparability[11,19] were rated as good quality studies with scores of 7/9 and 8/9, respectively. The remaining study[18], was rated as fair quality with a score of 6/9, largely due to its shorter follow-up period and higher rate of patients lost to follow-up. Overall, most studies were of good methodological quality, and their findings can be interpreted with a high degree of confidence (Table 2)[16-20,22,24]. The study[22], as an RCT, was assessed separately using the risk of bias 2 tool and rated as low risk overall. No studies were deemed critical, highlighting potential limitations in retrospective designs that could influence the reliability of pooled estimates (Supplementary Figure 5)[22].

GRADE assessment: The certainty of evidence is low for all primary outcomes due to the non-randomized nature of the studies, which introduces a high risk of bias. The evidence for procedure time and freedom from arrhythmia is further weakened by high inconsistency across studies. However, the finding of a lower risk of phrenic nerve palsy with PFA is consistent and precise, lending more confidence to this specific outcome despite the overall limitations. In contrast, the evidence for cardiac tamponade is rated as very low due to serious imprecision and a wide CI, making the effect size highly uncertain (Supplementary Table 3).

This meta-analysis synthesizes data from seven studies (six cohorts, one RCT) involving adults undergoing first-time PVI for paroxysmal or persistent AF, comparing PFA with CBA. Our findings indicate that PFA is associated with significantly shorter procedure times (MD = -15.24 minutes; 95%CI: -16.63 to -13.85; P < 0.00001), highlighting its procedural efficiency. The heterogeneity for procedure time was high (I2 = 89%), but dropped to a more moderate level (I2 = 63%) after the exclusion of the studies[11,20]. PFA also demonstrated a significantly lower risk of phrenic nerve palsy (OR = 0.17; 95%CI: 0.04-0.63; P = 0.008) with low heterogeneity (I2 = 0%), underscoring its tissue-selective properties. For clinical efficacy, PFA was associated with a significantly higher odds of one-year freedom from arrhythmia (OR = 1.27; 95%CI: 1.04-1.55; P = 0.02) with moderate heterogeneity (I2 = 45%). However, there was no significant difference in the risk of cardiac tamponade (OR = 2.11; 95%CI: 0.80-5.57; P = 0.13), repeat ablation (OR = 0.84; 95%CI: 0.65-1.09; P = 0.18), or vascular complications (OR = 0.96; 95%CI: 0.32-2.94; P = 0.96). Furthermore, no significant difference was observed for fluoroscopy time (MD = -0.06 minutes; 95%CI: -0.45 to 0.33; P = 0.77). The heterogeneity was substantial for repeat ablation (I2 = 75%) but dropped to a moderate level (I2 = 49%) after removing the study[17]. This finding suggests a need for further standardization of study protocols and patient populations. Strengths of this meta-analysis include adherence to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines, prospective PROSPERO registration, and a comprehensive search strategy across multiple databases, which minimized selection bias and enhanced reproducibility[25]. The use of a random-effects model appropriately accounted for anticipated heterogeneity, and sensitivity analyses confirmed the robustness of key findings, such as the reduced phrenic nerve palsy risk with PFA[26]. Additionally, risk of bias assessment via ROBINS-I provided a transparent evaluation, identifying moderate to serious concerns primarily in confounding and missing data domains[27].

Limitations encompass the inclusion of predominantly observational studies (only one RCT), which may introduce confounding despite propensity matching in some trials[28]. The small number of studies (n = 7) and participants (total n = 1456) limited statistical power for rare events like tamponade, potentially leading to false positives or negatives due to underpowered analyses. Asymmetrical funnel plots indicated potential publication bias for outcomes such as procedure time and phrenic nerve palsy, possibly underrepresenting negative results from smaller studies[29]. Heterogeneity remained high for procedural metrics, potentially driven by differences in operator experience, device generations, or AF subtypes, and the lack of RCTs precludes causal inferences[30]. Furthermore, follow-up was restricted to 1 year in most studies, limiting insights into long-term durability of lesions[31].

Our results align with emerging literature on non-thermal ablation technologies, where prior single-arm trials have reported PFA's rapid PVI achievement and safety advantages over thermal methods[32]. For instance, a recent multicenter registry echoed our findings on reduced phrenic nerve injury with PFA, attributing this to electroporation's cardiomyocyte specificity[33]. However, Conflicting evidence exists, as certain propensitymatched cohorts have reported no significant difference in tamponade rates between PFA and thermal modalities, potentially reflecting the impact of evolving catheter designs that mitigate early procedural risks[11]. In comparison to meta-analyses of CBA vs RFA, our pooled estimates for arrhythmia-free survival (approximately 70%-80% at 1 year) are consistent, but PFA's shorter procedure times suggest incremental efficiency gains[34]. Discrepancies with individual studies – for example, reports of higher fluoroscopy times in cryoballoondominant cohorts – may reflect anatomical variability or differences in imaging protocols that were not fully accounted for in our analysis[35]. These findings have important implications for clinical practice, where PFA may be preferred in patients at high risk for phrenic nerve palsy, such as those with prior diaphragmatic issues, while CBA remains suitable for cases prioritizing tamponade minimization[36]. Policy-wise, guidelines from bodies like the European Society of Cardiology should incorporate these comparative data to refine ablation recommendations, emphasizing patient-specific selection and operator training for PFA to address its learning curve[37]. For future research, large-scale RCTs with longer follow-up (> 2 years) and standardized outcome definitions are essential to clarify subgroup effects in persistent AF and assess cost-effectiveness[24,38,39]. Additionally, investigations into hybrid approaches or next-generation PFA devices could optimize safety profiles.

In summary, PFA offers procedural advantages over CBA in terms of shorter duration and reduced phrenic nerve palsy risk but carries a higher tamponade incidence, with comparable efficacy in arrhythmia control. Clinicians should weigh these trade-offs individually, and future RCTs are recommended to strengthen evidence for guideline updates.

| 1. | Chugh SS, Havmoeller R, Narayanan K, Singh D, Rienstra M, Benjamin EJ, Gillum RF, Kim YH, McAnulty JH Jr, Zheng ZJ, Forouzanfar MH, Naghavi M, Mensah GA, Ezzati M, Murray CJ. Worldwide epidemiology of atrial fibrillation: a Global Burden of Disease 2010 Study. Circulation. 2014;129:837-847. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2658] [Cited by in RCA: 3448] [Article Influence: 265.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wolf PA, Abbott RD, Kannel WB. Atrial fibrillation as an independent risk factor for stroke: the Framingham Study. Stroke. 1991;22:983-988. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4767] [Cited by in RCA: 5135] [Article Influence: 146.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kotalczyk A, Lip GY, Calkins H. The 2020 ESC Guidelines on the Diagnosis and Management of Atrial Fibrillation. Arrhythm Electrophysiol Rev. 2021;10:65-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Packer DL, Kowal RC, Wheelan KR, Irwin JM, Champagne J, Guerra PG, Dubuc M, Reddy V, Nelson L, Holcomb RG, Lehmann JW, Ruskin JN; STOP AF Cryoablation Investigators. Cryoballoon ablation of pulmonary veins for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation: first results of the North American Arctic Front (STOP AF) pivotal trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:1713-1723. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 552] [Cited by in RCA: 686] [Article Influence: 52.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kuck KH, Brugada J, Fürnkranz A, Metzner A, Ouyang F, Chun KR, Elvan A, Arentz T, Bestehorn K, Pocock SJ, Albenque JP, Tondo C; FIRE AND ICE Investigators. Cryoballoon or Radiofrequency Ablation for Paroxysmal Atrial Fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:2235-2245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1131] [Cited by in RCA: 1514] [Article Influence: 151.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Andrade JG, Wells GA, Deyell MW, Bennett M, Essebag V, Champagne J, Roux JF, Yung D, Skanes A, Khaykin Y, Morillo C, Jolly U, Novak P, Lockwood E, Amit G, Angaran P, Sapp J, Wardell S, Lauck S, Macle L, Verma A; EARLY-AF Investigators. Cryoablation or Drug Therapy for Initial Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:305-315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 264] [Cited by in RCA: 585] [Article Influence: 117.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Heeger CH, Sohns C, Pott A, Metzner A, Inaba O, Straube F, Kuniss M, Aryana A, Miyazaki S, Cay S, Ehrlich JR, El-Battrawy I, Martinek M, Saguner AM, Tscholl V, Yalin K, Lyan E, Su W, Papiashvili G, Botros MSN, Gasperetti A, Proietti R, Wissner E, Scherr D, Kamioka M, Makimoto H, Urushida T, Aksu T, Chun JKR, Aytemir K, Jędrzejczyk-Patej E, Kuck KH, Dahme T, Steven D, Sommer P, Richard Tilz R. Phrenic Nerve Injury During Cryoballoon-Based Pulmonary Vein Isolation: Results of the Worldwide YETI Registry. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2022;15:e010516. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 19.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Seidl P, Steinborn F, Costello-Boerrigter L, Surber R, Schulze PC, Böttcher C, Sommermeier A, Mattea V, Simeoni R, Malur FM, Lapp H, Schade A. Pulmonary vein isolation using second-generation single-shot devices: not all the same? J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2021;60:521-528. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Reddy VY, Neuzil P, Koruth JS, Petru J, Funosako M, Cochet H, Sediva L, Chovanec M, Dukkipati SR, Jais P. Pulsed Field Ablation for Pulmonary Vein Isolation in Atrial Fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;74:315-326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 189] [Cited by in RCA: 487] [Article Influence: 69.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Reddy VY, Anic A, Koruth J, Petru J, Funasako M, Minami K, Breskovic T, Sikiric I, Dukkipati SR, Kawamura I, Neuzil P. Pulsed Field Ablation in Patients With Persistent Atrial Fibrillation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76:1068-1080. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 299] [Article Influence: 49.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Marcon L, Della Rocca D, Magnocavallo M, Mene' R, Pannone L, Mohanty S, Glowniak A, Sousonis V, Sorgente A, Sarkozy A, Rossi P, Boveda S, Natale A, De Asmundis C, Chierchia GB. Pulsed electric field, cryoballoon, and radiofrequency for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation ablation: A propensity score-matched comparison. Europace. 2024;26:euae102.175. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Verma A, Haines DE, Boersma LV, Sood N, Natale A, Marchlinski FE, Calkins H, Sanders P, Packer DL, Kuck KH, Hindricks G, Onal B, Cerkvenik J, Tada H, DeLurgio DB; PULSED AF Investigators. Pulsed Field Ablation for the Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation: PULSED AF Pivotal Trial. Circulation. 2023;147:1422-1432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 390] [Article Influence: 130.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Turagam MK, Neuzil P, Schmidt B, Reichlin T, Neven K, Metzner A, Hansen J, Blaauw Y, Maury P, Arentz T, Sommer P, Anic A, Anselme F, Boveda S, Deneke T, Willems S, van der Voort P, Tilz R, Funasako M, Scherr D, Wakili R, Steven D, Kautzner J, Vijgen J, Jais P, Petru J, Chun J, Roten L, Füting A, Lemoine MD, Ruwald M, Mulder BA, Rollin A, Lehrmann H, Fink T, Jurisic Z, Chaumont C, Adeliño R, Nentwich K, Gunawardene M, Ouss A, Heeger CH, Manninger M, Bohnen JE, Sultan A, Peichl P, Koopman P, Derval N, Kueffer T, Rahe G, Reddy VY. Safety and Effectiveness of Pulsed Field Ablation to Treat Atrial Fibrillation: One-Year Outcomes From the MANIFEST-PF Registry. Circulation. 2023;148:35-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 246] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Aldaas OM, Malladi C, Han FT, Hoffmayer KS, Krummen D, Ho G, Raissi F, Birgersdotter-Green U, Feld GK, Hsu JC. Pulsed field ablation versus thermal energy ablation for atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of procedural efficiency, safety, and efficacy. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2024;67:639-648. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Blockhaus C, Guelker JE, Feyen L, Bufe A, Seyfarth M, Shin DI. Pulsed field ablation for pulmonary vein isolation: real-world experience and characterization of the antral lesion size compared with cryoballoon ablation. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2023;66:567-575. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kueffer T, Stettler R, Maurhofer J, Madaffari A, Stefanova A, Iqbal SUR, Thalmann G, Kozhuharov NA, Galuszka O, Servatius H, Haeberlin A, Noti F, Tanner H, Roten L, Reichlin T. Pulsed-field vs cryoballoon vs radiofrequency ablation: Outcomes after pulmonary vein isolation in patients with persistent atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm. 2024;21:1227-1235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Isenegger C, Arnet R, Jordan F, Knecht S, Krisai P, Völlmin G, Brügger J, Spreen D, Schaerli N, Subin B, Schär B, Formenti N, Mahfoud F, Sticherling C, Kühne M, Badertscher P. Pulsed-field ablation versus cryoballoon ablation in patients with persistent atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc. 2025;59:101684. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Schipper JH, Steven D, Lüker J, Wörmann J, van den Bruck JH, Filipovic K, Dittrich S, Scheurlen C, Erlhöfer S, Pavel F, Sultan A. Comparison of pulsed field ablation and cryoballoon ablation for pulmonary vein isolation. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol. 2023;34:2019-2026. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Urbanek L, Bordignon S, Schaack D, Chen S, Tohoku S, Efe TH, Ebrahimi R, Pansera F, Hirokami J, Plank K, Koch A, Schulte-Hahn B, Schmidt B, Chun KJ. Pulsed Field Versus Cryoballoon Pulmonary Vein Isolation for Atrial Fibrillation: Efficacy, Safety, and Long-Term Follow-Up in a 400-Patient Cohort. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol. 2023;16:389-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Maurhofer J, Kueffer T, Madaffari A, Stettler R, Stefanova A, Seiler J, Thalmann G, Kozhuharov N, Galuszka O, Servatius H, Haeberlin A, Noti F, Tanner H, Roten L, Reichlin T. Pulsed-field vs. cryoballoon vs. radiofrequency ablation: a propensity score matched comparison of one-year outcomes after pulmonary vein isolation in patients with paroxysmal atrial fibrillation. J Interv Card Electrophysiol. 2024;67:389-397. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Chandler J, Welch VA, Higgins JP, Thomas J. Updated guidance for trusted systematic reviews: a new edition of the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;10:ED000142. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1361] [Cited by in RCA: 3385] [Article Influence: 483.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 22. | Reichlin T, Kueffer T, Badertscher P, Jüni P, Knecht S, Thalmann G, Kozhuharov N, Krisai P, Jufer C, Maurhofer J, Heg D, Pereira TV, Mahfoud F, Servatius H, Tanner H, Kühne M, Roten L, Sticherling C; SINGLE SHOT CHAMPION Investigators. Pulsed Field or Cryoballoon Ablation for Paroxysmal Atrial Fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2025;392:1497-1507. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 86.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44932] [Cited by in RCA: 50772] [Article Influence: 10154.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 24. | Della Rocca DG, Marcon L, Magnocavallo M, Menè R, Pannone L, Mohanty S, Sousonis V, Sorgente A, Almorad A, Bisignani A, Głowniak A, Del Monte A, Bala G, Polselli M, Mouram S, La Fazia VF, Ströker E, Gianni C, Zeriouh S, Bianchi S, Sieira J, Combes S, Sarkozy A, Rossi P, Boveda S, Natale A, de Asmundis C, Chierchia GB; HRMC Investigators. Pulsed electric field, cryoballoon, and radiofrequency for paroxysmal atrial fibrillation ablation: a propensity score-matched comparison. Europace. 2023;26:euae016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 28.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18665] [Cited by in RCA: 18010] [Article Influence: 1059.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 26. | Sterne JA, Hernán MA, Reeves BC, Savović J, Berkman ND, Viswanathan M, Henry D, Altman DG, Ansari MT, Boutron I, Carpenter JR, Chan AW, Churchill R, Deeks JJ, Hróbjartsson A, Kirkham J, Jüni P, Loke YK, Pigott TD, Ramsay CR, Regidor D, Rothstein HR, Sandhu L, Santaguida PL, Schünemann HJ, Shea B, Shrier I, Tugwell P, Turner L, Valentine JC, Waddington H, Waters E, Wells GA, Whiting PF, Higgins JP. ROBINS-I: a tool for assessing risk of bias in non-randomised studies of interventions. BMJ. 2016;355:i4919. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7683] [Cited by in RCA: 12447] [Article Influence: 1244.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 27. | Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327:557-560. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39087] [Cited by in RCA: 48457] [Article Influence: 2106.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 28. | Andrade JG, Champagne J, Dubuc M, Deyell MW, Verma A, Macle L, Leong-Sit P, Novak P, Badra-Verdu M, Sapp J, Mangat I, Khoo C, Steinberg C, Bennett MT, Tang ASL, Khairy P; CIRCA-DOSE Study Investigators. Cryoballoon or Radiofrequency Ablation for Atrial Fibrillation Assessed by Continuous Monitoring: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Circulation. 2019;140:1779-1788. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 228] [Cited by in RCA: 452] [Article Influence: 64.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629-634. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34245] [Cited by in RCA: 42451] [Article Influence: 1463.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 30. | Wazni OM, Dandamudi G, Sood N, Hoyt R, Tyler J, Durrani S, Niebauer M, Makati K, Halperin B, Gauri A, Morales G, Shao M, Cerkvenik J, Kaplon RE, Nissen SE; STOP AF First Trial Investigators. Cryoballoon Ablation as Initial Therapy for Atrial Fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:316-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 224] [Cited by in RCA: 481] [Article Influence: 96.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Reddy VY, Gerstenfeld EP, Natale A, Whang W, Cuoco FA, Patel C, Mountantonakis SE, Gibson DN, Harding JD, Ellis CR, Ellenbogen KA, DeLurgio DB, Osorio J, Achyutha AB, Schneider CW, Mugglin AS, Albrecht EM, Stein KM, Lehmann JW, Mansour M; ADVENT Investigators. Pulsed Field or Conventional Thermal Ablation for Paroxysmal Atrial Fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2023;389:1660-1671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 407] [Cited by in RCA: 548] [Article Influence: 182.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Katov L, Teumer Y, Bothner C, Rottbauer W, Weinmann-Emhardt K. Comparative Analysis of Real-World Clinical Outcomes of a Novel Pulsed Field Ablation System for Pulmonary Vein Isolation: The Prospective CIRCLE-PVI Study. J Clin Med. 2024;13:7040. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Norrish G, Protonotarios A, Stec M, Boleti O, Field E, Cervi E, Elliott PM, Kaski JP. Performance of the PRIMaCY sudden death risk prediction model for childhood hypertrophic cardiomyopathy: implications for implantable cardioverter-defibrillator decision-making. Europace. 2023;25:euad330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Chun KRJ, Brugada J, Elvan A, Gellér L, Busch M, Barrera A, Schilling RJ, Reynolds MR, Hokanson RB, Holbrook R, Brown B, Schlüter M, Kuck KH; FIRE AND ICE Investigators. The Impact of Cryoballoon Versus Radiofrequency Ablation for Paroxysmal Atrial Fibrillation on Healthcare Utilization and Costs: An Economic Analysis From the FIRE AND ICE Trial. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6:e006043. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Scaglione M, Biasco L, Caponi D, Anselmino M, Negro A, Di Donna P, Corleto A, Montefusco A, Gaita F. Visualization of multiple catheters with electroanatomical mapping reduces X-ray exposure during atrial fibrillation ablation. Europace. 2011;13:955-962. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Hindricks G, Potpara T, Dagres N, Arbelo E, Bax JJ, Blomström-Lundqvist C, Boriani G, Castella M, Dan GA, Dilaveris PE, Fauchier L, Filippatos G, Kalman JM, La Meir M, Lane DA, Lebeau JP, Lettino M, Lip GYH, Pinto FJ, Thomas GN, Valgimigli M, Van Gelder IC, Van Putte BP, Watkins CL. Corrigendum to: 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): The Task Force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Developed with the special contribution of the European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J. 2021;42:4194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 296] [Article Influence: 59.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Calkins H, Hindricks G, Cappato R, Kim YH, Saad EB, Aguinaga L, Akar JG, Badhwar V, Brugada J, Camm J, Chen PS, Chen SA, Chung MK, Nielsen JC, Curtis AB, Davies DW, Day JD, d'Avila A, de Groot NMSN, Di Biase L, Duytschaever M, Edgerton JR, Ellenbogen KA, Ellinor PT, Ernst S, Fenelon G, Gerstenfeld EP, Haines DE, Haissaguerre M, Helm RH, Hylek E, Jackman WM, Jalife J, Kalman JM, Kautzner J, Kottkamp H, Kuck KH, Kumagai K, Lee R, Lewalter T, Lindsay BD, Macle L, Mansour M, Marchlinski FE, Michaud GF, Nakagawa H, Natale A, Nattel S, Okumura K, Packer D, Pokushalov E, Reynolds MR, Sanders P, Scanavacca M, Schilling R, Tondo C, Tsao HM, Verma A, Wilber DJ, Yamane T. 2017 HRS/EHRA/ECAS/APHRS/SOLAECE expert consensus statement on catheter and surgical ablation of atrial fibrillation: Executive summary. Europace. 2018;20:157-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 400] [Cited by in RCA: 383] [Article Influence: 47.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Wynn GJ, El-Kadri M, Haq I, Das M, Modi S, Snowdon R, Hall M, Waktare JE, Todd DM, Gupta D. Long-term outcomes after ablation of persistent atrial fibrillation: an observational study over 6 years. Open Heart. 2016;3:e000394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Fu YH, Chao TF, Yeh YH, Chan YH, Chien HT, Chen SA, Lin FJ. Atrial Fibrillation Screening in the Elderly: A Cost-Effectiveness Analysis for Public Health Policy. JACC Asia. 2025;5:160-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/