Published online Oct 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i29.8718

Peer-review started: June 2, 2021

First decision: June 22, 2021

Revised: July 3, 2021

Accepted: August 5, 2021

Article in press: August 5, 2021

Published online: October 16, 2021

Processing time: 134 Days and 21.8 Hours

For advanced gastric cancer patients with pancreatic head invasion, some studies have suggested that extended multiorgan resections (EMR) improves survival. However, other reports have shown high rates of morbidity and mortality after EMR. EMR for T4b gastric cancer remains controversial.

To evaluate the surgical approach for pT4b gastric cancer with pancreatic head invasion.

A total of 144 consecutive patients with gastric cancer with pancreatic head invasion were surgically treated between 2006 and 2016 at the China National Cancer Center. Gastric cancer was confirmed in 76 patients by postoperative pathology and retrospectively analyzed. The patients were divided into the gastrectomy plus en bloc pancreaticoduodenectomy group (GP group) and gastrectomy alone group (GA group) by comparing the clinicopathological features, surgical outcomes, and prognostic factors of these patients.

There were 24 patients (16.8%) in the GP group who had significantly larger lesions (P < 0.001), a higher incidence of advanced N stage (P = 0.030), and less neoadjuvant chemotherapy (P < 0.001) than the GA group had. Postoperative morbidity (33.3% vs 15.3%, P = 0.128) and mortality (4.2% vs 4.8%, P = 1.000) were not significantly different in the GP and GA groups. The overall 3-year survival rate of the patients in the GP group was significantly longer than that in the GA group (47.6%, median 30.3 mo vs 20.4%, median 22.8 mo, P = 0.010). Multivariate analysis identified neoadjuvant chemotherapy [hazard ratio (HR) 0.290, 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.103–0.821, P = 0.020], linitis plastic (HR 2.614, 95% CI: 1.024–6.675, P = 0.033), surgical margin (HR 0.274, 95% CI: 0.102–0.738, P = 0.010), N stage (HR 3.489, 95% CI: 1.334–9.120, P = 0.011), and postoperative chemoradiotherapy (HR 0.369, 95% CI: 0.163–0.836, P = 0.017) as independent predictors of survival in patients with pT4b gastric cancer and pancreatic head invasion.

Curative resection of the invaded pancreas should be performed to improve survival in selected patients. Invasion of the pancreatic head is not a contraindication for surgery.

Core tip: This was a retrospective study to evaluate the surgical approach for pT4b gastric cancer with pancreatic head invasion. The overall 3-year survival rate of the patients in the gastrectomy plus en bloc pancreaticoduodenectomy group was significantly longer than that in the gastrectomy alone group. Curative resection of the invaded pancreas should be performed to improve survival after balancing the risk and survival benefit.

- Citation: Jin P, Liu H, Ma FH, Ma S, Li Y, Xiong JP, Kang WZ, Hu HT, Tian YT. Retrospective analysis of surgically treated pT4b gastric cancer with pancreatic head invasion . World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(29): 8718-8728

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i29/8718.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i29.8718

Gastric cancer is the fifth most common cancer worldwide and the third leading cause of cancer-related mortality[1]. Advanced disease at presentation accounts for 39%–44% of newly diagnosed gastric cancer cases[2]. Despite improvements in early diagnosis and neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy, radical surgery is still the conventional curative treatment for gastric cancer. In patients with advanced gastric cancer, extended multiorgan resection (EMR) may be needed to achieve R0 resection. Some studies have suggested that EMR improves the survival rate of T4b patients[3-5]. However, other studies have shown high rates of morbidity and mortality after EMR[6]. Therefore, EMR for T4b gastric cancer remains controversial.

In advanced gastric cancer, the pancreas is the most frequently invaded organ. Min et al[7] reported that patients with pancreatic invasion had worse survival when they underwent pancreaticoduodenectomy. Postoperative pancreatic fistula is the most frequently reported complication after combined surgery. The performance of additional partial pancreatectomy and splenectomy to facilitate D2 lymphadenectomy was abandoned. This is because it increased the postoperative morbidity significantly without positive overall survival benefits[8,9]. The benefits of en bloc partial pancreatectomy for advanced gastric cancer with pancreatic invasion should be critically evaluated, given its potential of increased morbidity. However, only a few reports evaluating partial or total pancreatectomy for these patients have been published[5,10-13]. The aim of this study was to investigate the clinicopathological features, surgical outcomes, and prognostic factors of these patients.

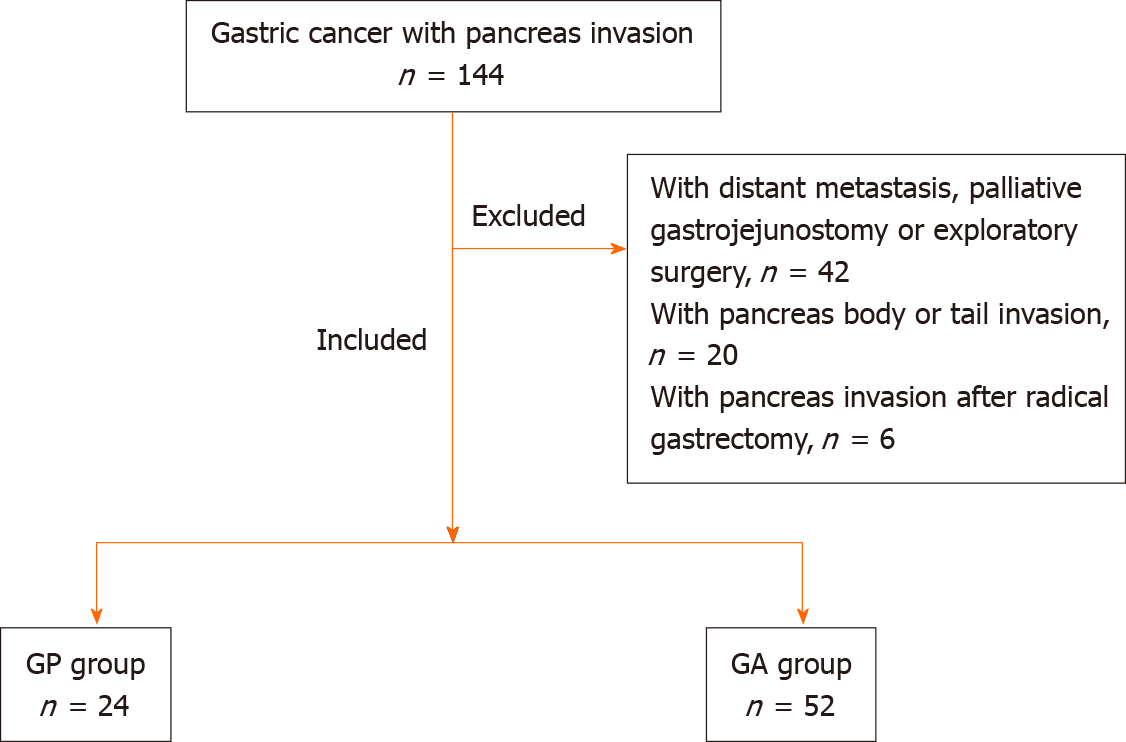

A total of 144 consecutive gastric cancer with pancreatic head invasion were surgically treated from January 2006 to December 2016 at our hospital. Of these patients, 76 who underwent surgery [gastrectomy combined with pancreatectomy (GP) or gastrectomy alone (GA)] with pancreatic invasion confirmed by postoperative pathology were enrolled. The remaining 68 patients underwent palliative bypass or exploratory surgery or with pancreas body/tail invasion, or with pancreas invasion after radical surgery. The study group consisted of 65 men (85.5%) and 11 women (14.5%) aged 28–74 years (mean 56.0 ± 10.7 years). The inclusion criteria were: (1) gastric cancer patients diagnosed with pancreatic head invasion who underwent curative gastrectomy combined with GP or GA; (2) patients without distant metastasis or other malignancies; and (3) patients with complete clinicopathological and follow-up records. The exclusion criteria were: (1) patients who underwent palliative gastrojejunostomy or exploratory surgery; (2) patients who presented with pancreatic metastasis after radical gastrectomy; and (3) patients with pancreatic body or tail invasion (Figure 1). T4 gastric cancer is defined according to the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) tumor node metastasis (TNM) system. Our study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, which was approved by the Institutional Review Board of our hospital (No. 14-067/857).

In cases where pancreatic invasion was considered during surgery, the curative-intent GP procedures were performed with en bloc gastrectomy combined with pancreaticoduodenectomy and D2 or D2+ lymphadenectomy. In contrast, en-bloc gastrectomy with D2 or D2+ lymphadenectomy without pancreatectomy (GA) was performed when the surgeon considered macroscopically inflammatory reactions, but postoperative pathology confirmed pancreatic invasion.

Clinicopathological variables included: age, gender, body mass index (BMI), preoperative albumin, preoperative hemoglobin, neoadjuvant chemotherapy, postoperative treatment, tumor size, Borrmann type, histological type, lymphova

Perioperative neoadjuvant or adjuvant chemotherapy (AC) after surgery was mainly based on fluorouracil in combination with platinum chemotherapy. The regimens were based on widely accepted studies[14,15]. Fifty-four patients who underwent neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) and 43 patients who underwent AC were included: 20 received S-1 plus oxaliplatin; 15 docetaxel, oxaliplatin and S-1; and eight capecitabine plus oxaliplatin. The median number of courses of AC was six (5–8), while that of NAC was three (2–4). A total of 33 patients received postoperative concurrent chemoradiotherapy, the dose of which was the same as that used in a previous study[16]. In case of recurrence, patients were advised to consult an oncolo

Patients were asked to re-examination every 3 mo for the first 2 years after surgery, then every 6 mo for 3 years, and annually thereafter. Clinicopathological features and survival data were obtained from electronic medical records, outpatient clinical visits and telephone interviews by the authors. Patients were followed up until death or December 31, 2020.

Statistical analyses were calculated with SPSS version 22.0. All continuous variables were assessed using the t test. Categorical variables were compared using the Fisher’s exact or χ2 tests. The Kaplan–Meier method was used to calculate cumulative survival rates and the log-rank test was used to evaluate statistically significant differences. Multivariate analysis of prognostic significance was performed using Cox’s proportional hazard model. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

In total, 76 gastric cancer patients with pancreatic head invasion who underwent surgical operation were enrolled from 2006 to 2016 in our hospital. Age, gender, BMI, American Society of Anesthesiologists scores, AC, histological type, Borrmann types, lymphatic and venous invasion, perineural invasion, preoperative albumin, and hemoglobin levels were comparable between the two groups. The percentage of patients receiving postoperative chemotherapy or chemoradiotherapy in the GA and GP groups had no significant difference (P = 0.199). However, NAC was administered more in the GA group than in the GP group (84.6% vs 41.7%, P < 0.001). Small tumor diameter (P < 0.001) was associated with the GA group. The GP group had a high N stage (P = 0.030), although the median number (n = 29) of harvested lymph nodes was similar between the two groups. The clinicopathological features of the 76 patients are summarized in Table 1.

| Variable | GP group, (n = 24) (%) | GA group, (n = 52) (%) | P value |

| Gender | 0.486 | ||

| Male | 22 (91.7) | 43 (82.7) | |

| Female | 2 (8.3) | 9 (17.3) | |

| Age (yr) | 0.254 | ||

| < 65 | 16 (66.7) | 41 (78.8) | |

| ≥ 65 | 8 (33.3) | 11 (21.2) | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 23.5 ± 3.5 | 23.2 ± 3.3 | 0.779 |

| ASA score | 0.45 | ||

| < 3 | 16 (66.7) | 39 (75.0) | |

| ≥ 3 | 8 (33.3) | 13 (25.0) | |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy | < 0.001 | ||

| Yes | 10 (41.7) | 44 (84.6) | |

| No | 14 (58.3) | 8 (15.4) | |

| Postoperative therapy | 0.199 | ||

| Chemotherapy | 11 (45.8) | 32 (61.5) | |

| Chemoradiotherapy | 13 (54.2) | 20 (38.5) | |

| Preoperative albumin (g/L) | 37.9 ± 4.9 | 36.3 ± 5.1 | 0.083 |

| Preoperative hemoglobin (g/L) | 119.0 ± 28.2 | 108.3 ± 26.5 | 0.058 |

| Linitis plastica | 0.059 | ||

| Yes | 1 (4.2) | 11 (21.2) | |

| No | 23 (95.8) | 41 (78.8) | |

| Borrmann type | 0.312 | ||

| I | 1 (4.2) | 1 (1.9) | |

| II | 8 (33.3) | 18 (34.6) | |

| III | 14 (58.3) | 23 (44.2) | |

| IV | 1 (4.2) | 10 (19.2) | |

| Tumor size (cm) | 9.3 ± 2.3 | 6.7 ± 1.9 | < 0.001 |

| Histological type | 0.945 | ||

| Poorly differentiated | 20 (83.3) | 43 (82.7) | |

| Well–moderately differentiated | 4 (16.7) | 9 (17.3) | |

| Pathological N stage | 0.03 | ||

| N0 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| N1 | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | |

| N2 | 5 (20.8) | 17 (32.7) | |

| N3a | 5 (20.8) | 16 (30.8) | |

| N3b | 14 (58.3) | 19 (36.5) | |

| Lymphovascular invasion | 0.168 | ||

| Yes | 22 (91.7) | 41 (78.8) | |

| No | 2 (8.3) | 11 (21.2) | |

| Neural invasion | 0.638 | ||

| Yes | 17 (70.8) | 34 (65.4) | |

| No | 7 (29.2) | 18 (34.6) | |

| Surgical margin | < 0.001 | ||

| R0 | 21 (87.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| R1 | 3 (12.5) | 52 (88.5) |

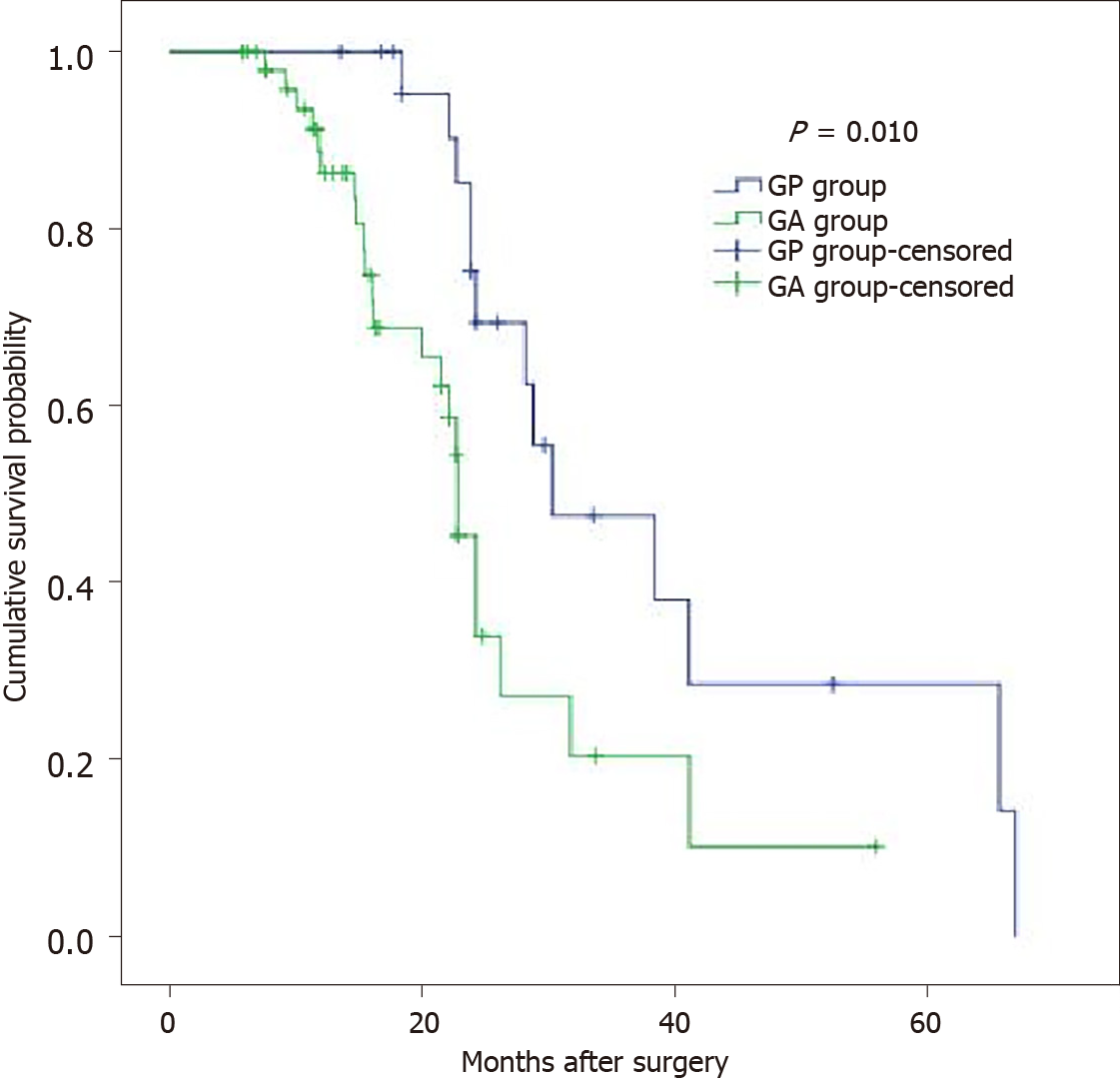

The overall perioperative 30-d mortality (4.2% vs 4.8%, P = 1.000) and postoperative morbidity (33.3% vs 15.3% P = 0.128) were similar in the GP and GA groups. Those in the GP group had longer operation times (223.3 ± 41.6 vs 192.9 ± 29.6, P = 0.003) and postoperative hospital stays (18.2 ± 5.9 vs 10 ± 3.6, P < 0.001) than those in the GA group. The details of the operation and postoperative complications are summarized in Table 2. The overall 3-year survival rate of the pT4 patients in the GP group was significantly longer than that in the GA group (47.6%, median 30.3 mo vs 20.4%, median 22.8 mo, P = 0.010) (Figure 2).

| Variable | GP group, (n = 24) (%) | GA group, (n = 52) (%) | P value |

| Intraoperative blood loss (mL) | 443.8 ± 104.6 | 144.2 ± 64.7 | < 0.001 |

| Operation time (min) | 223.3 ± 41.6 | 192.9 ± 29.6 | 0.003 |

| Postoperative hospital stay (d) | 18.2 ± 5.9 | 10 ± 3.6 | < 0.001 |

| Postoperative mortality | 1 (4.2) | 2 (3.8) | 1 |

| Postoperative morbidity | 8 (33.3) | 8 (15.3) | 0.128 |

| Local complications | 5 (20.8) | 6 (11.5) | 0.324 |

| Abdominal infection | 1 | 0 | |

| Anastomotic fistula | 0 | 1 | |

| Abdominal hemorrhage | 1 | 0 | |

| Gastrointestinal hemorrhage | 0 | 1 | |

| Disruption of wound | 1 | 0 | |

| Pancreatic fistula | 2 | 3 | |

| Duodenal stump fistula | 0 | 1 | |

| Systemic complications | 3 (12.5) | 2 (3.8) | 0.177 |

| Pulmonary infection | 1 | 0 | |

| Pneumothorax | 1 | 1 | |

| Renal failure | 0 | 0 | |

| Diabetic ketoacidosis | 1 | 0 | |

| Cardio- and cerebrovascular event | 0 | 1 | |

| Clavien–Dindo classification | 0.309 | ||

| II | 1 | 3 | |

| IIIa | 2 | 1 | |

| IIIb | 3 | 1 | |

| IVa | 1 | 0 | |

| IVb | 0 | 1 | |

| V | 1 | 2 |

Of all the prognostic factors evaluated, tumor type (linitis plastica/not), tumor diameter, NAC (yes/no), N stage, operation type, lymphovascular invasion (yes/no), surgical margin (R0/R1), and postoperative treatment (chemotherapy/chemoradiotherapy) were statistically significant by univariate analysis. Only NAC (P = 0.020), tumor type (linitis plastica/not) (P = 0.033), N stage (P = 0.011), surgical margin (R0/R1) (P = 0.010), and postoperative treatment (P = 0.017) were identified as independent prognostic factors by multivariate survival analysis (Table 3). Surgical margin (R0/R1) was identified as the most powerful prognostic factor.

| Variable | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||

| HR (95%CI) | ||||

| P value | HR (95%CI) | P value | ||

| Age ≥ 65/< 65 yr | 1.19 (0.567–2.505) | 0.644 | — | — |

| Gender (male/female) | 1.01 (0.369–2.101) | 0.346 | — | — |

| Preoperative hemoglobin < 35 g/L (yes/no) | 1.09 (0.423–3.205) | 0.524 | — | — |

| Preoperative anemia | 1.18 (0.523–2.985) | 0.502 | — | — |

| (hemoglobin < 90 g/L) (yes/no) | ||||

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (yes/no) | 0.180 (0.073–0.446) | < 0.001 | 0.29 (00.103–0.821) | 0.02 |

| Operation type (GP/GA) | 0.393 (0.188–0.819) | 0.013 | 0.689 (0.157–3.019) | 0.621 |

| Borrmann type | 0.159 | — | — | |

| I | 1 | |||

| II | 1.399 (0.266–7.358) | 0.692 | ||

| III | 0.479 (0.164–1.403) | 0.179 | ||

| IV | 0.398 (0.144–1.100) | 0.076 | ||

| Tumor diameter > 7/≤ 7 cm | 0.380 (0.190–0.758) | 0.006 | — | — |

| Tumor type (linitis plastica/not) | 2.764 (1.127–6778) | 0.026 | 2.614 (1.024–6.675) | 0.033 |

| Intraoperative blood loss > 400mL (yes/no) | 1.089 (0.347–2.102) | 0.154 | ||

| Operation time > 240 min | 1.021 (0.233–3.112) | 0.423 | ||

| Surgical margin (R0/R1) | 2.501 (1.177–5.314) | 0.017 | 0.274 (0.102–0.738) | 0.01 |

| Lymphovascular invasion (yes/no) | 2.512 (1.066–5.921) | 0.035 | 1.517 (0.930–2.476) | 0.095 |

| Perineural invasion (yes/no) | 1.545 (0.781–3.054) | 0.211 | — | — |

| Differentiation type (poor/well–moderate) | 1.358 (0.610–3.021) | 0.454 | — | — |

| N stage(N0/N1/N2/N3a/N3b) | 1.708 (1.103–2.644) | 0.016 | 3.489 (1.334–9.120) | 0.011 |

| Postoperative treatment (chemotherapy/chemoradiotherapy) | 0.347 (0.159–0.757) | 0.008 | 0.369 (0.163–0.836) | 0.017 |

There are few reports that have directly evaluated partial or total pancreatectomy due to confined tumor invasion to the pancreas. Most studies evaluated EMR as one group. Some patients underwent radical gastrectomy with extended en bloc resection of the head or tail of the pancreas to achieve R0 resection. However, with macroscopic assessment of organ involvement in preoperative and intraoperative staging, it is sometimes difficult to distinguish histological invasion from peritumoral inflammation. Some patients who underwent gastrectomy alone, were identified to be pT4b with pancreatic invasion in the final postoperative histological examination. The present study is novel in that it directly assessed the prognostic factors for the patients in the two groups.

The predictive value of computed tomography in identifying T4 disease was found to be ≤ 50%[17]. The accuracy of endoscopic ultrasound was only 46.2% for T stage and 66.7% for N stage. The incidence of pathologically confirmed T4 cancers was found to be 38.1% by intraoperative assessment. Previous studies reported that pathological invasion was confirmed in only 14%–65% of gastric cancer patients treated with EMR[4,18-20]. All patients who underwent EMR were confirmed with pancreatic invasion in our study. Comparison between the GP and GA groups demonstrated that patients with larger lesions, higher N stage and less NAC were associated with a higher possibility of receiving GP. Given the significantly poorer survival with R1/R2 resection and the difficulty of perioperative assessment, we recommend that GP should be performed in patients with T4b gastric cancer for curative resection. The alternative of “peeling” an adherent tumor off of the pancreas carries a high risk of leaving behind a positive margin.

Of the prognostic factors evaluated, only NAC, N stage, surgical margin (R0/R1), tumor type, and postoperative treatment were identified as independent prognostic factors by multivariate analysis (Table 3). The cumulative 3-year survival rate of the T4b patients in the GP group was significantly longer than that in the GA group. Previous reports demonstrated that the 5-year survival rate of the patients with the R0 resection was 30.6%–37.8%. The percentage of R0 resection after multivisceral resection was 38%–100%. Tran et al[18] reported that R0 resection rate reached 100% in 34 patients after additional partial pancreatectomy. Our results also suggested that R0 resection was an important prognostic factor associated with improved survival for T4b gastric cancer with pancreatic invasion.

Lymph node metastasis was reported to be one of the important prognostic factors in patients with gastric cancer. Yasuo reported that patients with pN3 lymph node metastasis have dismal prognosis even if R0 resection is achieved and thus those patients may be not suitable candidates for GP. In the present study, the prognosis of patients with N2 lymph node metastasis was significantly better than the prognosis of those with N3 lymph node metastasis.

With major advances in systemic chemotherapy for advanced gastric cancer, the median survival of patients has been prolonged to > 12 mo. In particular, NAC has been used as a treatment option. In our study, patients treated with NAC had significantly better survival. However, as a national cancer center, we have patients from all over the country. Different patients received different treatments, which was a limitation of our study. Becker et al[21] reported that nearly 50% of patients with locally advanced gastric cancer were downstaged by NAC. Recently, a meta-analysis showed morbidity and perioperative mortality were not influenced by NAC[22]. Therefore, we recommend that NAC should be considered first, followed by GP in patients with pancreatic invasion. Furthermore, patients presenting with progression on perioperative therapy or who cannot tolerate chemotherapy should be excluded from GP.

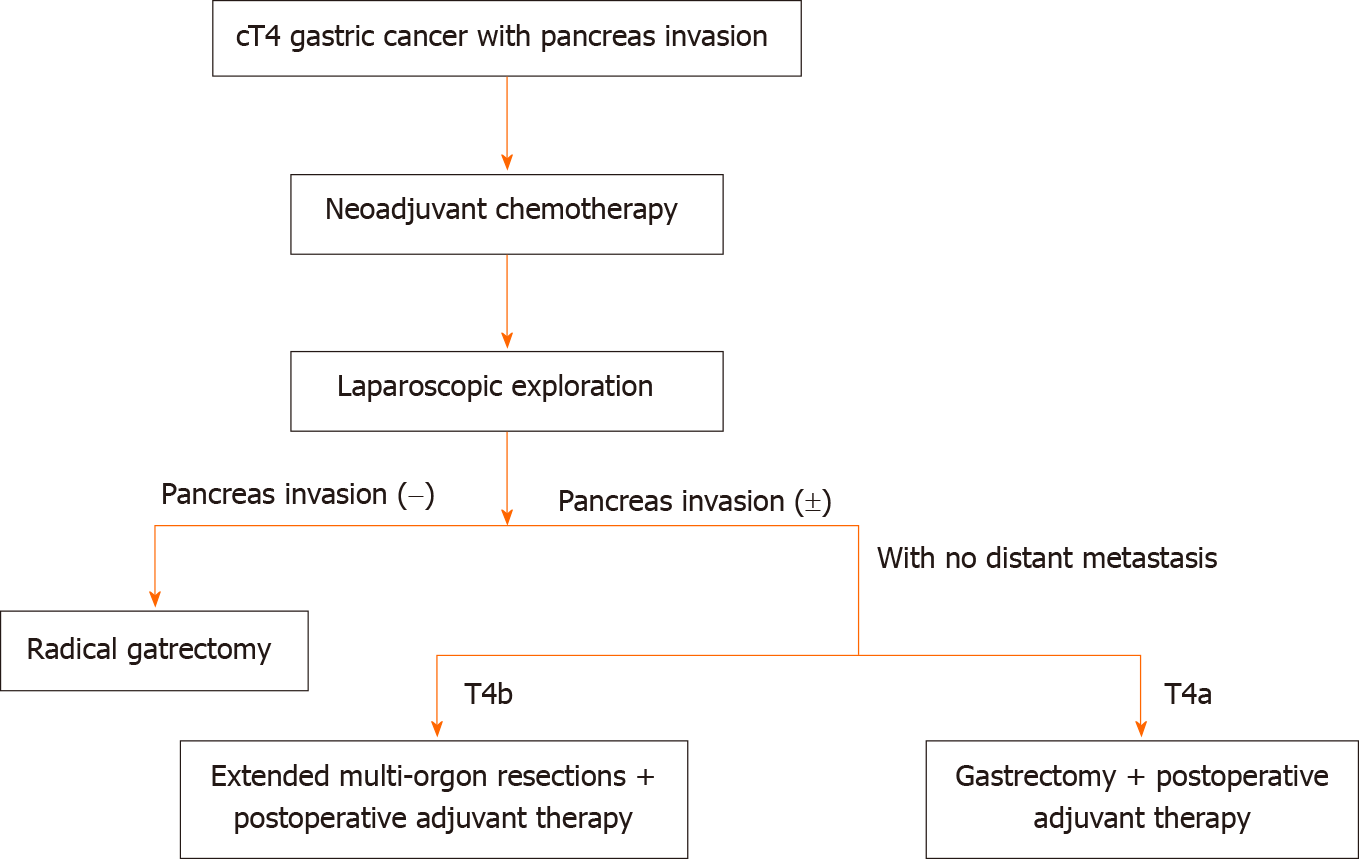

Tran et al[18] reported a significantly higher percentage of Clavien–Dindo grade ≥ III complications for patients with gastric cancer undergoing gastrectomy with partial pancreatectomy. Another study showed that patients with postoperative complications had a threefold increased likelihood of not receiving AC[23]. In our study, the overall perioperative 30-d mortality (4.2% vs 4.8%, P = 1.000) and postoperative morbidity (33.3% vs 15.3% P = 0.128) were similar in the GP and GA groups. There were no surgery-related deaths in our study. Therefore, we recommend an algorithm for the management of the related patients as Figure 3 showed.

NAC followed by a curative resection including radical gastrectomy, extensive lymph node dissection, and en bloc resection of invaded pancreas plus postoperative chemoradiotherapy might be considered as a valid treatment option to improve the survival rate of patients with pT4b gastric cancer with pancreatic head invasion. However, it should be cautiously performed in selected patients. It may be worthwhile to perform a pR0 resection after balancing the risk and survival benefit. Large randomized control trials are needed to confirm the results.

For advanced gastric cancer patients with pancreatic head invasion, extended multiorgan resection remains controversial.

This study investigated the clinicopathological features, surgical outcomes, and prognostic factors of these patients.

This study aimed to evaluate the surgical approach for pT4b gastric cancer with pancreatic head invasion.

A total of 143 consecutive gastric cancer with pancreatic head invasion were surgically treated between 2006 and 2016 at the China National Cancer Center. Of these patients, 76 confirmed by postoperative pathology were retrospectively analyzed. They were divided into the gastrectomy plus en bloc pancreaticoduodenectomy group (GP group) and gastrectomy alone group (GA group). The clinicopathological features, surgical outcomes, and prognostic factors of these patients were compared.

The GP group had significantly larger lesions (P < 0.001), higher incidence of advanced N stage cancer (P = 0.030), and less neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NAC) (P < 0.001) than the GA group. Postoperative morbidity (33.3% vs 15.3% P = 0.128) and mortality (4.2% vs 4.8%, P = 1.000) were not significantly different in the GP and GA groups. The overall 3-year survival rate of the patients in the GP group was significantly longer than that in the GA group (47.6%, median 30.3 mo vs 20.4%, median 22.8 mo, P = 0.010). Multivariate analysis identified NAC [hazard ratio (HR) 0.290; 95% confidence interval (CI): 0.103–0.821; P = 0.020], linitis plastic (HR 2.614; 95% CI: 1.024–6.675, P = 0.033), surgical margin (HR 0.274; 95% CI: 0.102–0.738; P = 0.010), N stage (HR 3.489; 95% CI: 1.334–9.120, P = 0.011), and postoperative chemoradiotherapy (HR 0.369; 95% CI: 0.163–0.836, P = 0.017) as independent predictors of survival in patients with pT4b gastric cancer and pancreatic head invasion.

NAC followed by curative resection including radical gastrectomy, extensive lymph node dissection, and en bloc resection of invaded pancreas plus postoperative chemoradiotherapy might be considered as a valid treatment option to improve the survival rate of patients with pT4b gastric cancer with pancreatic head invasion.

Surgical role for T4b patients.

| 1. | Wang FH, Shen L, Li J, Zhou ZW, Liang H, Zhang XT, Tang L, Xin Y, Jin J, Zhang YJ, Yuan XL, Liu TS, Li GX, Wu Q, Xu HM, Ji JF, Li YF, Wang X, Yu S, Liu H, Guan WL, Xu RH. The Chinese Society of Clinical Oncology (CSCO): clinical guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of gastric cancer. Cancer Commun (Lond). 2019;39:10. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 271] [Cited by in RCA: 316] [Article Influence: 45.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Brenner H, Rothenbacher D, Arndt V. Epidemiology of stomach cancer. Methods Mol Biol. 2009;472:467-477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 374] [Cited by in RCA: 415] [Article Influence: 24.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Shchepotin IB, Chorny VA, Nauta RJ, Shabahang M, Buras RR, Evans SR. Extended surgical resection in T4 gastric cancer. Am J Surg. 1998;175:123-126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Martin RC 2nd, Jaques DP, Brennan MF, Karpeh M. Extended local resection for advanced gastric cancer: increased survival versus increased morbidity. Ann Surg. 2002;236:159-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 150] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | van der Werf LR, Eshuis WJ, Draaisma WA, van Etten B, Gisbertz SS, van der Harst E, Liem MSL, Lemmens VEPP, Wijnhoven BPL, Besselink MG, van Berge Henegouwen MI; Dutch Upper Gastrointestinal Cancer Audit (DUCA) group. Nationwide Outcome of Gastrectomy with En-Bloc Partial Pancreatectomy for Gastric Cancer. J Gastrointest Surg. 2019;23:2327-2337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Cuschieri A, Fayers P, Fielding J, Craven J, Bancewicz J, Joypaul V, Cook P. Postoperative morbidity and mortality after D1 and D2 resections for gastric cancer: preliminary results of the MRC randomised controlled surgical trial. The Surgical Cooperative Group. Lancet. 1996;347:995-999. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 700] [Cited by in RCA: 696] [Article Influence: 23.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Min JS, Jin SH, Park S, Kim SB, Bang HY, Lee JI. Prognosis of curatively resected pT4b gastric cancer with respect to invaded organ type. Ann Surg Oncol. 2012;19:494-501. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Cuschieri A, Weeden S, Fielding J, Bancewicz J, Craven J, Joypaul V, Sydes M, Fayers P. Patient survival after D1 and D2 resections for gastric cancer: long-term results of the MRC randomized surgical trial. Surgical Co-operative Group. Br J Cancer. 1999;79:1522-1530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 994] [Cited by in RCA: 1001] [Article Influence: 37.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 9. | Bonenkamp JJ, Songun I, Hermans J, Sasako M, Welvaart K, Plukker JT, van Elk P, Obertop H, Gouma DJ, Taat CW. Randomised comparison of morbidity after D1 and D2 dissection for gastric cancer in 996 Dutch patients. Lancet. 1995;345:745-748. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 772] [Cited by in RCA: 737] [Article Influence: 23.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Toh BC, Rao J. Laparoscopic D2 total gastrectomy and en-mass splenectomy and distal pancreatectomy for locally advanced proximal gastric cancer. Surg Endosc. 2018;32:2156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Piso P, Bellin T, Aselmann H, Bektas H, Schlitt HJ, Klempnauer J. Results of combined gastrectomy and pancreatic resection in patients with advanced primary gastric carcinoma. Dig Surg. 2002;19:281-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sakamoto Y, Sakaguchi Y, Sugiyama M, Minami K, Toh Y, Okamura T. Surgical indications for gastrectomy combined with distal or partial pancreatectomy in patients with gastric cancer. World J Surg. 2012;36:2412-2419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Ojima T, Nakamura M, Hayata K, Yamaue H. Robotic D2 total gastrectomy with en-mass removal of the spleen and body and tail of the pancreas for locally advanced gastric cancer. Surg Oncol. 2020;35:22-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bang YJ, Kim YW, Yang HK, Chung HC, Park YK, Lee KH, Lee KW, Kim YH, Noh SI, Cho JY, Mok YJ, Ji J, Yeh TS, Button P, Sirzén F, Noh SH; CLASSIC trial investigators. Adjuvant capecitabine and oxaliplatin for gastric cancer after D2 gastrectomy (CLASSIC): a phase 3 open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2012;379:315-321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1267] [Cited by in RCA: 1332] [Article Influence: 95.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sasako M, Sakuramoto S, Katai H, Kinoshita T, Furukawa H, Yamaguchi T, Nashimoto A, Fujii M, Nakajima T, Ohashi Y. Five-year outcomes of a randomized phase III trial comparing adjuvant chemotherapy with S-1 versus surgery alone in stage II or III gastric cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:4387-4393. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 869] [Cited by in RCA: 1119] [Article Influence: 74.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Macdonald JS, Smalley SR, Benedetti J, Hundahl SA, Estes NC, Stemmermann GN, Haller DG, Ajani JA, Gunderson LL, Jessup JM, Martenson JA. Chemoradiotherapy after surgery compared with surgery alone for adenocarcinoma of the stomach or gastroesophageal junction. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:725-730. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2465] [Cited by in RCA: 2461] [Article Influence: 98.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Colen KL, Marcus SG, Newman E, Berman RS, Yee H, Hiotis SP. Multiorgan resection for gastric cancer: intraoperative and computed tomography assessment of locally advanced disease is inaccurate. J Gastrointest Surg. 2004;8:899-902. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Tran TB, Worhunsky DJ, Norton JA, Squires MH 3rd, Jin LX, Spolverato G, Votanopoulos KI, Schmidt C, Weber S, Bloomston M, Cho CS, Levine EA, Fields RC, Pawlik TM, Maithel SK, Poultsides GA. Multivisceral Resection for Gastric Cancer: Results from the US Gastric Cancer Collaborative. Ann Surg Oncol. 2015;22 Suppl 3:S840-S847. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Cheng CT, Tsai CY, Hsu JT, Vinayak R, Liu KH, Yeh CN, Yeh TS, Hwang TL, Jan YY. Aggressive surgical approach for patients with T4 gastric carcinoma: promise or myth? Ann Surg Oncol. 2011;18:1606-1614. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ozer I, Bostanci EB, Orug T, Ozogul YB, Ulas M, Ercan M, Kece C, Atalay F, Akoglu M. Surgical outcomes and survival after multiorgan resection for locally advanced gastric cancer. Am J Surg. 2009;198:25-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Becker K, Langer R, Reim D, Novotny A, Meyer zum Buschenfelde C, Engel J, Friess H, Hofler H. Significance of histopathological tumor regression after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in gastric adenocarcinomas: a summary of 480 cases. Ann Surg. 2011;253:934-939. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 185] [Cited by in RCA: 294] [Article Influence: 19.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Coccolini F, Nardi M, Montori G, Ceresoli M, Celotti A, Cascinu S, Fugazzola P, Tomasoni M, Glehen O, Catena F, Yonemura Y, Ansaloni L. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy in advanced gastric and esophago-gastric cancer. Meta-analysis of randomized trials. Int J Surg. 2018;51:120-127. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Schouwenburg MG, Busweiler LAD, Beck N, Henneman D, Amodio S, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Cats A, van Hillegersberg R, van Sandick JW, Wijnhoven BPL, Wouters MWJ, Nieuwenhuijzen GAP; Dutch Upper GI Cancer Audit group. Hospital variation and the impact of postoperative complications on the use of perioperative chemo(radio)therapy in resectable gastric cancer. Results from the Dutch Upper GI Cancer Audit. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2018;44:532-538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Oncology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): E

P-Reviewer: Pruthi DS, Toriumi T S-Editor: Yan JP L-Editor: Kerr C P-Editor: Guo X