Published online Aug 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i23.6929

Peer-review started: May 6, 2021

First decision: June 6, 2021

Revised: June 7, 2021

Accepted: June 22, 2021

Article in press: June 22, 2021

Published online: August 16, 2021

Processing time: 91 Days and 9.5 Hours

Blue rubber bleb naevus syndrome (BRBNS) is a rare disease that usually presents with multiple venous malformations in the skin and gastrointestinal tract. Lesions located in the gastrointestinal tract always result in chronic gastrointestinal bleeding and severe anemia. The successful management of BRBNS with sirolimus had been reported in many institutions, due to its impact on signaling pathways of angiogenesis. However, the experience in treatment of neonates with BRBNS was limited.

A 38-day-old premature female infant born with multiple skin lesions, presented to our center complaining of severe anemia and hematochezia. Laboratory examination demonstrated that hemoglobin was 5.3 g/dL and contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomography showed multiple low-density space-occupying lesions in the right lobe of the liver. She was diagnosed as having BRBNS based on typical clinical and examination findings. The patient was treated by transfusions twice and hemostatic drugs but symptoms of anemia were difficult to alleviate. A review of BRBNS case reports found that patients had been successfully treated with sirolimus. Then the patient was treated with sirolimus at an average dose of 0.95 mg/m2/d with a target drug level of 10-15 ng/mL. During 28 mo of treatment, the lesion was reduced, hemoglobin returned to normal, and there were no adverse drug reactions.

This case highlights the dosing regimen and plasma concentration in neonates, for the current common empiric dose is high.

Core Tip: Sirolimus is considered as a first-line drug in treating patients with blue rubber bleb naevus syndrome currently. We present herein successful, long-term treatment of blue rubber bleb naevus syndrome with sirolimus in an infant with the youngest age reported. This case highlights two aspects: The recommended doses of 0.1 mg/kg/d resulted in a plasma concentration that was far beyond the expected 10-15 ng/mL in neonates, and a high plasma concentration of more than 20 ng/mL is associated with a great improvement in the condition. Thus, the dosing regimen and plasma concentration are special in neonates.

- Citation: Yang SS, Yang M, Yue XJ, Tou JF. Sirolimus treatment for neonate with blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(23): 6929-6934

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i23/6929.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i23.6929

Blue rubber bleb naevus syndrome (BRBNS) is an extremely uncommon disorder featured by multifocal venous malformations[1], primarily the cutaneous and gastrointestinal systems[2]. Gastrointestinal bleeding which is slow, chronic, and occult, and secondary iron deficiency anemia are major symptoms and potentially life-threatening[3]. Individuals often experience multiple blood transfusions and lifelong iron supplementation with worsening quality of life[4]. Life expectancy is normal as long as gastrointestinal bleeding is controlled and no severe complications occur[5].

There is no consensus regarding the management of BRBNS. The use of sirolimus in the treatment of BRBNS was first reported by Yuksekkaya et al[6] in 2012, and reports of successful treatment with sirolimus have been well described in some cases since then, with the majority of cases having an age older than 5 years[7]. Sirolimus appears to be considered as a first-line drug, with minimal side effects and the strong cumulative evidence during the treatment. However, reports indicate that BRBNS is detectable at birth or early infancy[8]. To our knowledge, there have been no reports of sirolimus used in infants aged less than 3 mo. Here we describe BRBNS in a 1-mo-old premature infant treated with sirolimus and discuss the important clinical findings including interventions and outcomes, dosing regimen, and plasma concentration with high- vs low-dose treatment.

A 38-day-old female infant was admitted to our institution with persistent severe anemia and hematochezia.

The patient was born with multiple skin lesions and severe anemia, and was found to have hematochezia 2 d ago. The scattered dark-bule cutaneous lesions had gradually increased in size and number over time. She had been hospitalized only one time and had supportive therapy during this period.

The child (G5P1, gestational age of 35 + 5 wk) was delivered via cesarean section due to placental hemangioma.

The patient had a free family history of BRBNS.

The patient’s weight was 2.8 kg, height was 47 cm, and head circumference was 33 cm, all of which were all in the third percentile. Her temperature was 37.4 ℃, respiratory rate was 36 breaths/min, heart rate was 144 bpm, and blood pressure was 69/30 mmHg. She was pale with widespread lesions on the scalp, face, mouth, trunk, arms, legs, and fingers on admission.

Blood analysis demonstrated severe anemia (hemoglobin: 5.3 g/dL; hematocrit: 17.1%; mean corpuscular volume: 98.8 fL/red cell; serum iron: 11.6 μmol/L; serum ferritin: 88.9 μg/L) and coagulopathy (D-dimer: 1.13 mg/L; fibrinogen: 0.81 g/L), and white blood cell count and platelet count were normal. The fecal occult blood test was positive. Liver function tests revealed total bilirubin 180.7 μmol/L, direct bilirubin 23.3 μmol/L, and indirect bilirubin 157.4 μmol/L; alanine aminotransferase and aspartate aminotransferase were normal. Renal function and myocardial enzyme were within the normal range.

Contrast-enhanced abdominal computed tomography showed multiple low-density space-occupying lesions in the right lobe of the liver. And they measured 81.6 mm × 53.8 mm, 52.2 mm × 42.4 mm, 44.6 mm × 40.7 mm, 23.6 mm × 35.0 mm, respectively. Abdominal ultrasound revealed low echoes in bilateral adrenal glands, with a size of 2.6 cm × 1.4 cm × 1.1 cm in the left and 1.6 cm × 1.1 cm × 0.8 cm in the right. Color Doppler flow imaging showed abundant blood flow signal.

The patient was diagnosed as having BRBNS based on typical clinical and examination findings with severe anemia and gastrointestinal hemorrhage.

The patient had undergone transfusions per 0.5 U for twice and treatment with hemostatic agents of etamsylate injection and aminomethylbenzoic acid injection for the symptoms of anemia and gastrointestinal blood losses. A review of BRBNS case reports found that patients had been successfully treated with sirolimus. The parents of the child were informed about the side effects of sirolimus, and informed consent was received from the family. When the transfusions had failed in the remission of anemia, the patient was then treated with sirolimus at a dose of 0.28 mg/d (0.1 mg/kg) and propranolol at 2 mg/d incrementally to 5 mg/d, administered twice daily at approximately 12-h intervals. She was monitored for heart rate, blood pressure, and laboratory examination closely after the initiation of sirolimus and propranolol.

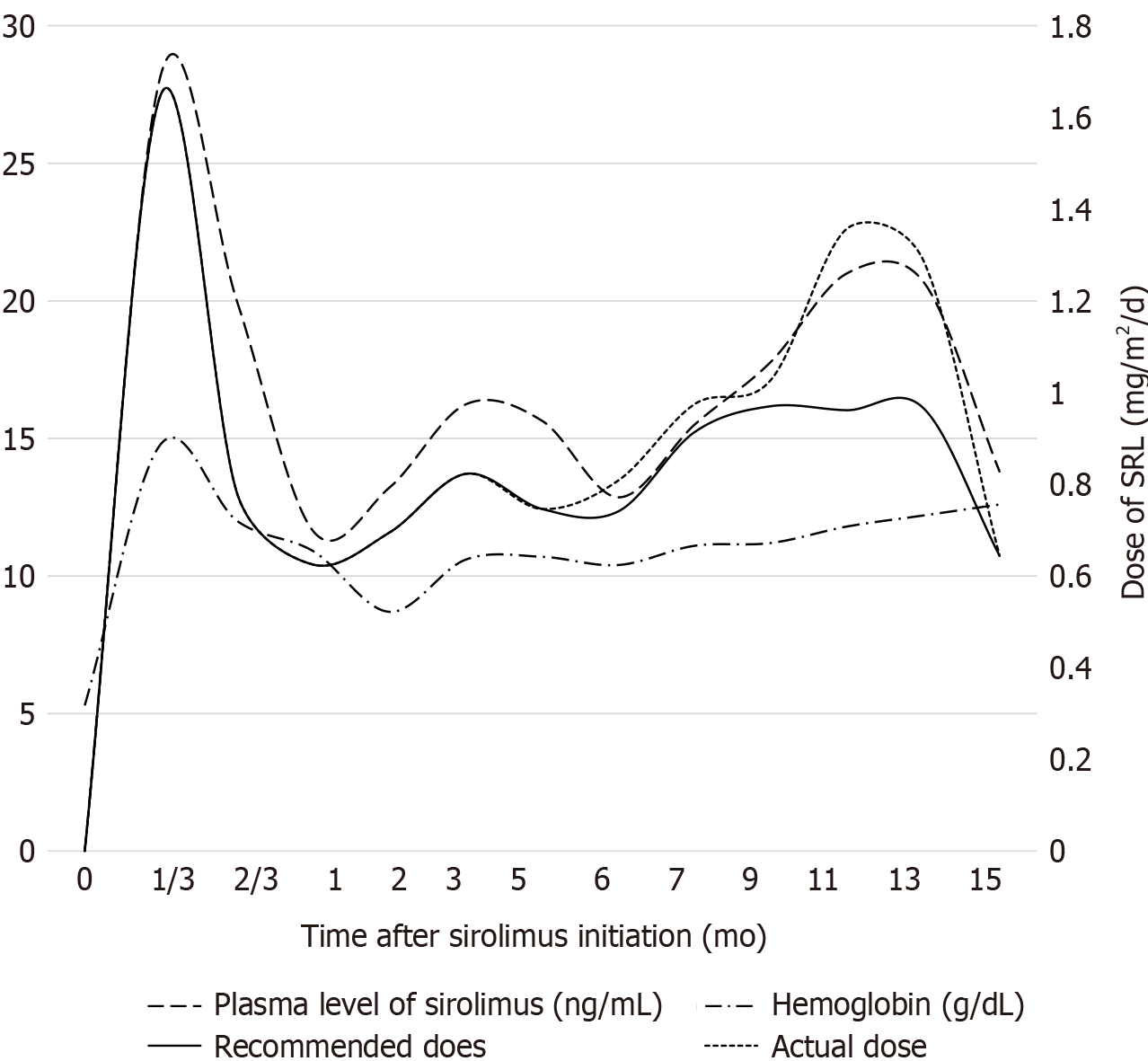

Within 4 d of pharmacological therapy, the hemoglobin level was increased from 5.3 g/dL to 11.8 g/dL significantly, and the positive fecal occult blood test turned negative. The patient was followed for 28 mo and her guardian was asked to keep detailed records of symptoms and side effects. The plasma concentration of sirolimus was measured, laboratory tests including blood test and blood biochemical examination were performed, and lesion size and number were evaluated every 1-3 mo in the early and 5-8 mo in the late after treatment. Dose of sirolimus was adjusted according to the test results and patient’s response to the medication, and propranolol was stopped 2 mo later. The patient was responsive to sirolimus treatment with skin lesions being smaller and numbers being decreased. Now she is under therapy with only sirolimus (over 28 mo). Figure 1 records the dose and plasma concentration of sirolimus, and hemoglobin concentration during the follow-up. The cutaneous lesions showed a marked regression, the hemoglobin concentrations normalized, and chronic gastrointestinal bleeding was controlled. Response is reported as transfusion-independent, increased weight (from 3th to nearly 50th), and improved quality of life with fewer clinical treatment. The patient did experience cough once without fever, and sirolimus was not stopped. No adverse events were observed, including hepatic damage, renal dysfunction, oral stomatitis, hypercholesterol, cytopenia, and opportunistic infections.

It was observed that the hemoglobin concentration was 8.7 g/L, below normal value, which was considered neonatal physiological anemia. We did treat her with iron replacement, but not blood transfusion.

BRBNS is a benign venous malformation, which is diagnosed mainly based on clinical examination. A literature search of PubMed was performed to retrieve publications reporting cases of BRBNS treated with sirolimus. In 17 studies recording the treatment and follow-up of 40 patients, the outcomes indicate much hope in management of BRBNS with sirolimus. There were 39% patients with no side effect. Adverse effects included mucositis (46.3%), acne (7.3%), elevation of liver enzymes (4.9%), hypercholesterolaemia (4.9%), neutropenia (4.9%), hair loss (2.4%), thrombocytopenia (2.4%), and severe soft tissue infection (2.4%). Even if adverse effects occurred, they can be resolved by adjusting the dose, except for one patient in whom severe soft tissue infection developed and the treatment was stopped.

Consideration of the dose of sirolimus is related to the potentially adverse side effects, and the dosing regimen is the issue that needs to be answered, as there is no clear protocol. Currently there are two recommended dosing regimens, one based on body weight (0.1 mg/kg/d)[9] and the other based on body surface area (1.6 mg/m2/d)[10]. The calculated dose of drug obtained by two methods was different, and the subtle distinction may lead to large fluctuations in blood drug concentrations for newborns. Our patient was treated with sirolimus at the recommended beginning doses of 0.1 mg/kg/d, administered twice daily at approximately 12-h intervals. However, the measured plasma concentration of sirolimus was 28.23 ng/mL after 4 d of treatment, far beyond the expected plasma level of 10-15 ng/mL. We realized that the difference between our case and the other cases in the literature is that our patient was an only 1-mo-old premature infant, who was much younger than the reported cases. The difference in blood drug concentration was explained mainly by the age difference. We then adjusted the dose according to the infant's body weight and the characteristics of drug absorption to maintain a plasma level of 10-15 ng/mL. The adjusted dose was 0.24 ± 0.09 (ranged from 0.12 to 0.36) mg/d. The conversion results are both much lower than the recommended doses, as 0.03 ± 0.01 (range from 0.02 to 0.05) mg/kg/d based on body weight, and 0.81 ± 0.13 (range from 0.62 to 0.97) mg/m2/d based on body surface area. To find a more suitable dose for neonates, we review the literature related to sirolimus used in neonates with other disorders. One case report suggested a dose of 0.4 mg/m2 twice a day based on the goal levels clinically[11]. One study showed the proposed dose regimens for each age group, such as 0.4 mg/m2/dose twice a day for 0-1 mo, 0.5 for 1-2 mo, 0.6 for 2-3 mo, and so on, which was based on the developmental changes in pharmacokinetics[12]. In conclusion, initial sirolimus doses appear to be 0.8 mg/m2 for neonates since concentrations of 10-15 ng/mL are effective and safe[13], and the calculated result of conversion by body surface area is more accurate.

However, these improvements became less obvious as the treatment progressed. The patient’s parents were dissatisfied with this response and then gradually increased the dose based on the adjusted dose in private. In particular, the average increased dose of 0.13 mg/d during 2 mo caused the plasma sirolimus level to rise above 20 ng/mL sharply but the effect was significant. The size and color of the lesions were reduced once again, and some of them even disappeared. When the presence of elevated sirolimus levels in blood was discovered, we reiterated the adverse reactions of sirolimus and asked the parents to administer the dose strictly. Then the plasma level returned to a stable level after dropping.

During the course of treatment, there were two periods of blood drug concentration exceeding the expected range. The first time was the initial medication used, and the second time was the parents adjusting dose in private. In both of these periods, the size and color of the lesions were reduced significantly, and some of them even disappeared, with no rebound after the blood concentration was reduced, which is an interesting phenomenon. This second event started from March 2019. Especially when the average increased dose of 0.13 mg/d during 2 mo caused the plasma sirolimus level to rise above 20 ng/mL, the effect was significant. There were no obvious side effects during the two stages. This serendipity leads us to think and propose a different direction of dosing regimen. A lower dose of sirolimus treatment had been more pursued in the past, providing the same therapeutic effect while minimizing side effects[14]. But our case may provide the possibility that a high dose may be used to improve the condition at the bottleneck stage. A high plasma level is associated with a higher risk of side effects. But medication adherence will be reduced for a long period of medication when parents become anxious based on the reports. And the long-term use of sirolimus may expose patients to potentially adverse side effects. Given this lack of data, the high-dose regimen mentioned in this study will provide a meaningful starting point for optimal doses for different stages of BRBNS. And the standardization of dosing and acceptable plasma sirolimus level will require further discussion and confirmation.

We present the case of a premature baby with BRBNS, who had a good response to sirolimus with no AEs. Treatment should be monitored and aimed at controlling the lesions of BRBNS. The correct dose of sirolimus is still not clear, but the current common empiric dose may be too high in neonates. Attention should be paid to recommended sirolimus doses for neonates and the more accurate calculation conversion. We believe that sirolimus will become an acceptable and preferred treatment for BRBNS in the future. Prior to the pursuit of low-dose sirolimus, a high dosing regimen may be alternative.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Beraldo RF S-Editor: Wu YXJ L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Wang LYT

| 1. | Sullivan CA. Blue Rubber Bleb Nevus Syndrome. Anesthesiology. 2018;129:1169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Margolin JF, Soni HM, Pimpalwar S. Medical therapy for pediatric vascular anomalies. Semin Plast Surg. 2014;28:79-86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wong XL, Phan K, Rodríguez Bandera AI, Sebaratnam DF. Sirolimus in blue rubber bleb naevus syndrome: A systematic review. J Paediatr Child Health. 2019;55:152-155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Menegozzo CAM, Novo FDCF, Mori ND, Bernini CO, Utiyama EM. Postoperative disseminated intravascular coagulation in a pregnant patient with Blue Rubber Bleb Nevus Syndrome presenting with acute intestinal obstruction: Case report and literature review. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2017;39:235-238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Baigrie D, Rice AS, An IC. Blue Rubber Bleb Nevus Syndrome. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, 2021. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Yuksekkaya H, Ozbek O, Keser M, Toy H. Blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome: successful treatment with sirolimus. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e1080-e1084. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 100] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Fernández Gil M, López Serrano P, García García E. Successful management of anemia with sirolimus in blue rubber bleb nevus syndrome: case report and update. Rev Esp Enferm Dig. 2019;111:643-647. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Isoldi S, Belsha D, Yeop I, Uc A, Zevit N, Mamula P, Loizides AM, Tabbers M, Cameron D, Day AS, Abu-El-Haija M, Chongsrisawat V, Briars G, Lindley KJ, Koeglmeier J, Shah N, Harper J, Syed SB, Thomson M. Diagnosis and management of children with Blue Rubber Bleb Nevus Syndrome: A multi-center case series. Dig Liver Dis. 2019;51:1537-1546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ünlüsoy Aksu A, Sari S, Eğritaş Gürkan Ö, Dalgiç B. Favorable Response to Sirolimus in a Child With Blue Rubber Bleb Nevus Syndrome in the Gastrointestinal Tract. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2017;39:147-149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Akyuz C, Susam-Sen H, Aydin B. Blue Rubber Bleb Nevus Syndrome: Promising Response To Sirolimus. Indian Pediatr. 2017;54:53-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Cabrera TB, Speer AL, Greives MR, Goff DA, Menon NM, Reynolds EW. Sirolimus for Kaposiform Hemangioendothelioma and Kasabach-Merritt Phenomenon in a Neonate. AJP Rep. 2020;10:e390-e394. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Mizuno T, Fukuda T, Emoto C, Mobberley-Schuman PS, Hammill AM, Adams DM, Vinks AA. Developmental pharmacokinetics of sirolimus: Implications for precision dosing in neonates and infants with complicated vascular anomalies. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017;64. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Adams DM, Trenor CC 3rd, Hammill AM, Vinks AA, Patel MN, Chaudry G, Wentzel MS, Mobberley-Schuman PS, Campbell LM, Brookbank C, Gupta A, Chute C, Eile J, McKenna J, Merrow AC, Fei L, Hornung L, Seid M, Dasgupta AR, Dickie BH, Elluru RG, Lucky AW, Weiss B, Azizkhan RG. Efficacy and Safety of Sirolimus in the Treatment of Complicated Vascular Anomalies. Pediatrics. 2016;137:e20153257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 454] [Cited by in RCA: 567] [Article Influence: 56.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Salloum R, Fox CE, Alvarez-Allende CR, Hammill AM, Dasgupta R, Dickie BH, Mobberley-Schuman P, Wentzel MS, Chute C, Kaul A, Patel M, Merrow AC, Gupta A, Whitworth JR, Adams DM. Response of Blue Rubber Bleb Nevus Syndrome to Sirolimus Treatment. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016;63:1911-1914. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |