Published online Aug 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i23.6900

Peer-review started: April 24, 2021

First decision: May 24, 2021

Revised: June 3, 2021

Accepted: June 16, 2021

Article in press: June 16, 2021

Published online: August 16, 2021

Processing time: 102 Days and 21.9 Hours

Scrub typhus is an acute infectious disease caused by rickettsia infection. The diagnosis is based on eschar, and clinical manifestations can range from asymptomatic to multiorgan dysfunction.

We report the case of a 35-year-old man living in Zhuhai, Guangdong, China, who had repeated high fever with a maximum body temperature of 40.2 °C and elevated white blood cells and procalcitonin levels. After 7 d of persistent high fever, the patient developed rash, abdominal pain, and symptoms of peritonitis. Within 24 h after admission, the patient developed diffuse peritonitis and pneumonedema, requiring ventilator support in the intensive care unit. However, there was no eschar on the body, and the first Weil-Felix test was negative. Taking into account that the patient had a history of jungle activities, doxycycline combined with meropenem was selected. The patient improved, healed, and was discharged after a week. The diagnosis of scrub typhus was confirmed by a repeat Weil-Felix test (Oxk 1:640), and pathology of the appendix resected by laparotomy suggests vasculitis.

This rare presentation of peritonitis, pulmonary edema, and pancreatitis caused by scrub typhus reminds physicians to be alert to the possibility of scrub typhus.

Core Tip: We report a case of scrub typhus mainly manifesting as diffuse peritonitis, pulmonary edema, and other multiorgan dysfunction, but lacking typical eschar, and the first Weil-Felix test was negative. Tracing back his travel history of jungle activities 5 d before the onset, doxycycline (100 mg q12h) was added empirically to cover atypical bacteria. He was finally discharged in a relatively stable condition under appropriate antibiotics including meropenem and doxycycline 7 d after admission. This rare presentation of peritonitis, pulmonary edema, and pancreatitis caused by scrub typhus reminds physicians to be alert to the possibility of scrub typhus.

- Citation: Zhou XL, Ye QL, Chen JQ, Li W, Dong HJ. Manifestation of acute peritonitis and pneumonedema in scrub typhus without eschar: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(23): 6900-6906

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i23/6900.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i23.6900

Scrub typhus is a zoonotic acute infectious disease caused by Orientia tsutsugamushi, which is transmitted to humans by the bite of a larval Leptotrombidium mite (chigger mite)[1]. The disease occurs mainly in the Asia-Pacific region, including China, peaking from June to July[2,3]. It is estimated that more than half of the world's population (55%) live in areas where scrub typhus is endemic, and approximately one million cases are reported annually[4]. Studies have shown that people of all ages are susceptible to scrub typhus, and people with exposure in fields or orchards for a long time are at high risk[5,6]. The main clinical manifestations of scrub typhus include eschar, lymphadenopathy, and skin rash. Among them, eschar is the key for diagnosis of scrub typhus, with a detection rate of 46%-86%[7]. However, some cases lack eschar and multiorgan dysfunction manifestations. Scrub typhus combined with peritonitis or pneumonedema has rarely been reported, and there are no reports about tsutsugamushi combined with peritonitis and pneumonedema[8].

Herein, we report the case of a 35-year-old man with diffuse peritonitis that appeared after a week of high fever of unknown origin. As the condition worsened, complications such as pneumonedema, respiratory failure, mental disorder, pancreatitis, and myocardial damage appeared. Physical examination revealed lymphadenopathy in the right inguinal region and a skin rash on the trunk and limbs, but no eschar was found on the entire body.

Abdominal pain.

A 35-year-old man from Zhuhai Guangdong, China had a spiking high fever of up to 40.2 °C without respiratory, digestive, or urinary symptoms. However, the patient’s fever persisted, even after taking antibiotics and symptomatic treatment in an outpatient clinic. A week later, he went to the emergency room with a complaint of severe abdominal pain, and inflammation indicators were significantly high. Therefore, he was transferred to our ward for further treatment of acute fever and peritonitis of unknown origin.

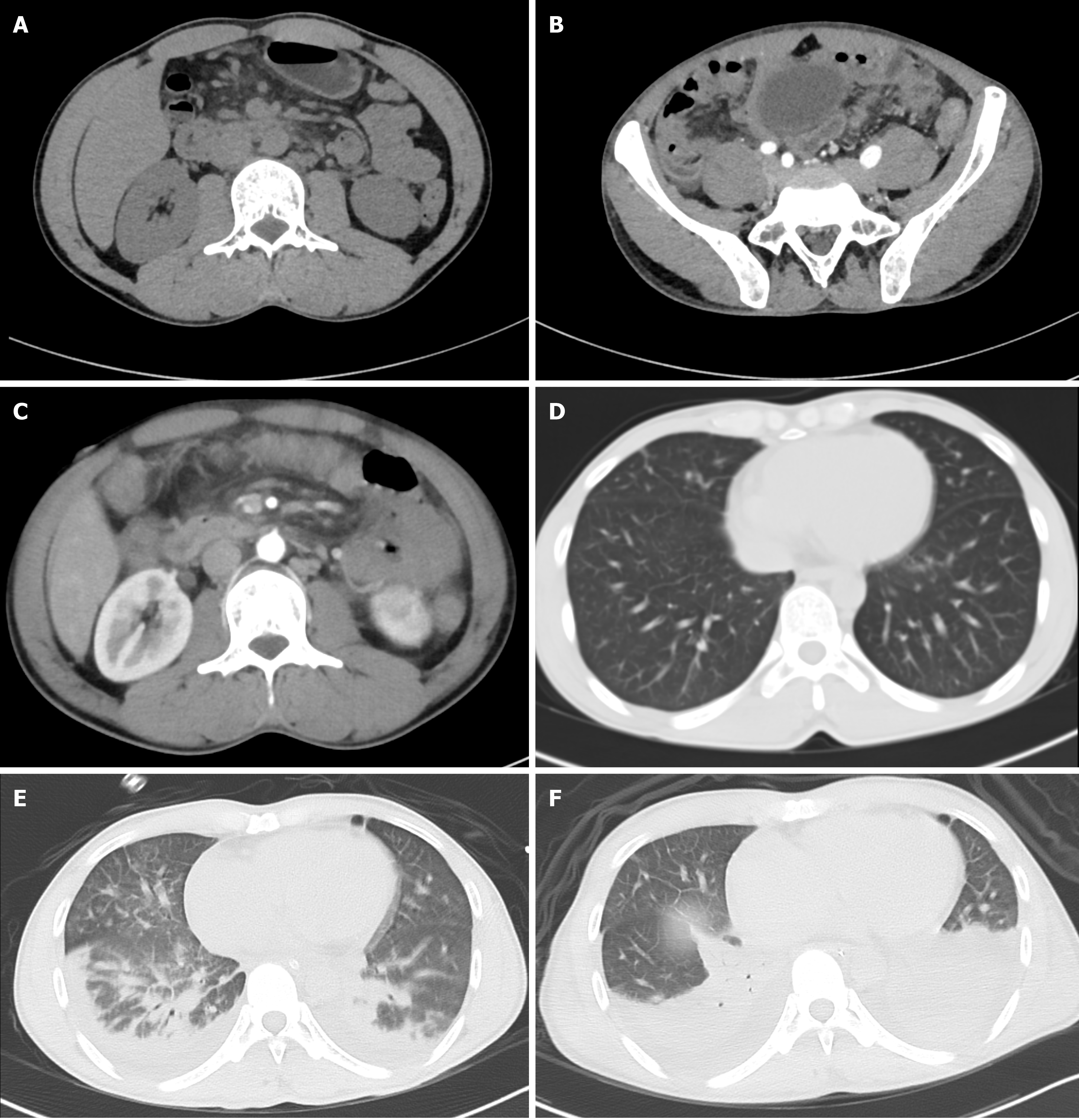

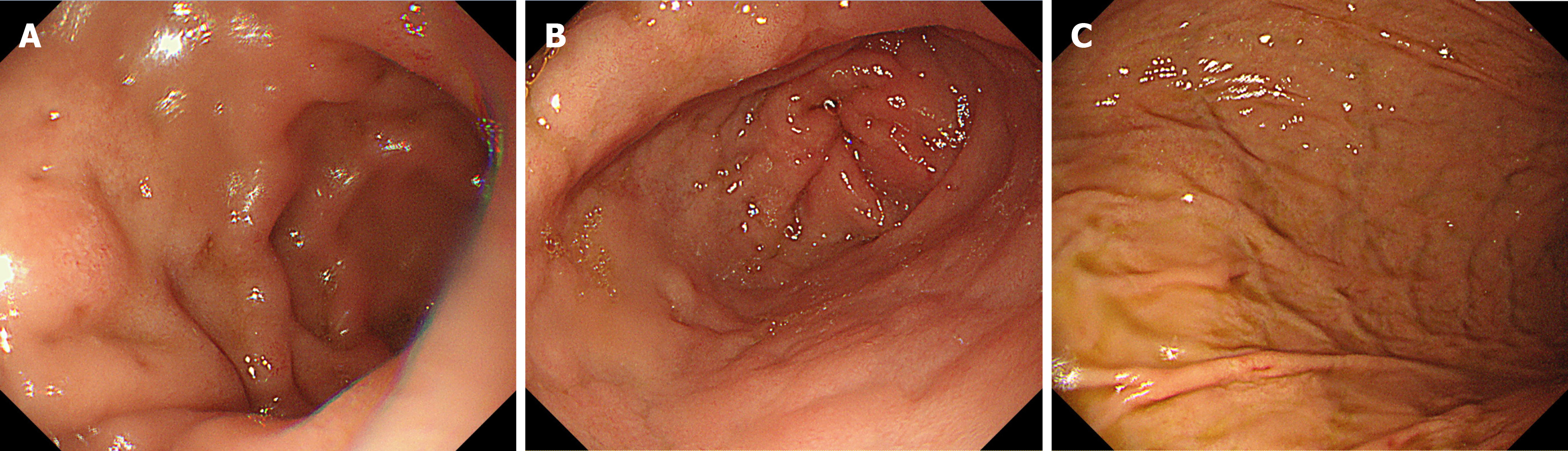

The patient received antibiotics (cefoperazone sodium and sulbactam sodium injection 3 g q8h) and supportive treatments on the first evening of hospitalization. However, his condition deteriorated the next morning. The patient developed diffuse peritonitis and blurred consciousness. Examination revealed direct tenderness and rebound tenderness in the whole abdomen (obvious in the right upper abdomen) and emerging pulmonary rales. Although meropenem (1 g q8h) was selected for countering infection, the patient's condition continued to deteriorate in the afternoon, with unconsciousness, irritability, a decreased oxygenation index (pO2/FiO2 = 230), and a body temperature above 39.0 °C. Computed tomography (CT) examinations of the head, chest, and entire abdomen revealed no new signs, except for pulmonary edema (Figure 1A-E). We urgently performed gastroscopy and laparotomy, and removed the enlarged appendix, but failed to clarify the cause of infection (Figure 2). The patient's condition continued to deteriorate, with deterioration of organ function (amylase increased to 884 U/L and troponin to 977 ng/L) and lung consolidation (Figure 1F). Respiratory failure occurred, and continuous assisted ventilation was required.

The patient had no history of systemic diseases.

The patient denied alcohol, tobacco, or recreational drug use. There was no family or genetic history. The patient had a history of jungle activities 5 d before onset.

The patient’s body temperature was 40.2 °C; his heart rate was 113 bpm, respiratory rate was 30 breaths per minute, blood pressure was 90/56 mmHg, and oxygen saturation was 95%. Lung examination revealed crackles and wheezing. Examination revealed direct tenderness and rebound tenderness of the whole abdomen (obvious in the right upper abdomen), rash on the trunk and limbs, and swollen lymph nodes in the groin area.

Laboratory examinations revealed functional damage: White blood cells (13.27 × 109/L), C-reactive protein (195.12 mg/L), blood amylase (412.00 U/L), and procalcitonin (3.15 ng/mL) increased, platelets (99 × 109/L) decreased, and liver (alanine transaminase 72.7 U/L) and kidney function indexes (creatinine 115 µmol/L) increased. In addition, a Weil-Felix test was negative.

A plain CT scan of the upper abdomen on the first day of hospitalization revealed inflammatory exudation of the peritoneum, with multiple small lymph nodes in the posterior peritoneum (Figure 1A). A plain CT scan on the second day of hospitalization showed peritonitis, an enlarged appendix (approximately 9 mm in diameter), and multiple small lymph nodes behind the peritoneum. Unexpectedly, there was pleural effusion and pulmonary edema in both lungs, which CT did not detect the day before (Figure 1B-E). During the operation on the second day of hospitalization, there was mild edema in the head of the appendix, with a small amount of light-yellow clear ascites in the abdominal cavity. The small intestine and colon were dilated, mild edema in the head of the pancreas and a few saponification spots in the pancreas and posterior peritoneum were noted, but no perforation was observed in the gastric wall or small intestine.

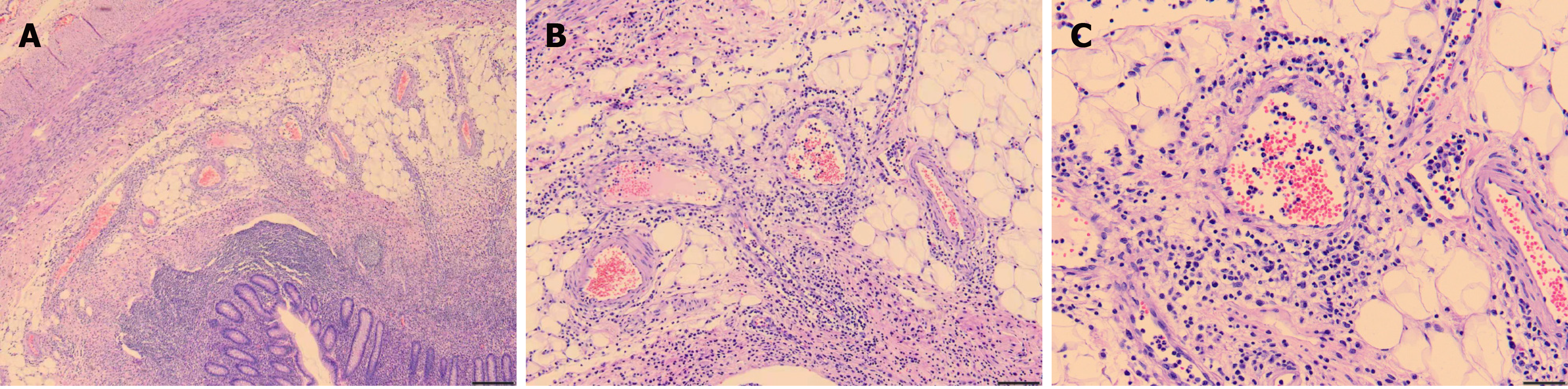

The diagnosis of scrub typhus was based on the following: (1) The patient lived in an endemic area of scrub typhus and had a history of jungle activities before onset; (2) The patient had typical symptoms of fever, rash, and lymphadenopathy; (3) Conventional antibiotics were ineffective, but doxycycline was effective; and (4) The repeated Weil-Felix test was positive on the sixth day after admission (Oxk 1:640). Moreover, the pathology of the appendix suggested vasculitis (Figure 3).

Tracing back his travel history, the patient had a history of jungle activities 5 d before onset. At this point (the third day of hospitalization), doxycycline (100 mg q12h) was added empirically for atypical bacteria.

Fortunately, on the fifth day of hospitalization, the patient’s temperature began to gradually decrease, and organ damage also improved (the oxygen level rose to 304, amylase decreased to 441 U/L, and troponin decreased to 220 ng/L). He was finally discharged in a relatively stable condition under treatment with appropriate antibiotics, including meropenem and doxycycline, at 7 d after admission and was followed in our outpatient department. Two weeks after discharge, the patient returned for follow-up, and organ function indexes, such as transaminase, troponin, and amylase, had all returned to normal.

This case of scrub typhus mainly manifested as diffuse peritonitis, pulmonary edema, and other multiorgan dysfunction but lacked typical eschar, and the first Weil-Felix test was negative.

Scrub typhus is a zoonotic disease caused by the rickettsia Orientia tsutsugamushi, an intracellular microorganism. The pathogenic virulence of this pathogen varies by region and strain. After an incubation period of 6-21 d, the disease is characterized by fever, eschar, lymphadenopathy, skin rash, and gastrointestinal symptoms. These nonspecific clinical manifestations of scrub typhus may hinder diagnosis. The key to diagnosis depends on clinical manifestations, epidemiological history, and finding typical eschar, which results from a bite from the chigger, causing local inflammation, edema, necrosis, and scabbing[9,10].

The pathophysiology of scrub typhus is disseminated vasculitis with subsequent vascular injury that involves organs such as the skin, liver, brain, kidney, meninges, and lungs[11]. Therefore, scrub typhus is a multisystem damaging disease that may cause serious complications, such as acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), shock, acute kidney failure, hepatic dysfunction, myocarditis, disseminated intravascular coagulation, and multisystem organ failure, or even death, with a reported mortality rate as high as 35%-60% if diagnosis or appropriate therapy is delayed[9]. Goswami et al[4] reported that a 20-year-old man with scrub typhus, who was misdiagnosed with the common cold, developed respiratory failure and liver failure, requiring ventilator support in the intensive care unit. A large prospective study on scrub typhus showed that when accompanied by complications, mortality increases: ARDS 29.7%, renal failure 29.7%, sensory changes 24.4%, and shock 38.4%[12].

The presentation of our patient was unusual. First, no eschars or ulcers were found in multiple physical examinations, though this sign is key for the diagnosis of scrub typhus. Studies have also documented an eschar detection rate of 46%-86%[7]. It is worth noting that in a large retrospective analysis of 418 patients confirmed to have scrub typhus with eschar, there were significant differences in the distribution of eschars between males and females[13]. In females, eschar was primarily present on the chest and abdomen (42.3%); in males, it was present on the axilla, groin, and genitalia (55.8%). Unusual sites of eschar in the cheek, ear lobe, and dorsum of the feet have also been reported[13]. The chances of a misdiagnosis also increase in the absence of rash or a typical eschar or the presence of eschar on hidden areas of the body, such as the scrotum or axilla. Furthermore, the current patient's condition deteriorated sharply after admission, with multiorgan dysfunction. Peritonitis and pancreatitis in patients with scrub typhus have rarely been found. Lee et al[14] reported two cases of scrub typhus with abdominal pain, which were confirmed to involve perforation of the digestive tract by surgery and were cured by doxycycline. One study of seven patients with pancreatitis who were diagnosed with scrub typhus reported that six patients had multiple organ dysfunction, three patients who had ≥ 4 organs involved died, and the mortality rate was as high as 42.8%[15]. However, the mechanism of abdominal pain and peritonitis remains unclear. Praveen Kumar et al[16] reported that Orientia tsutsugamushi targets endothelial cells and macrophages, through which it disseminates into multiple organs via hematogenous and lymphomatous circulation. The pathogen has also been reported to be predominantly located in macrophages of the liver and spleen[17], which may explain the severe pain in our patient's right abdomen. According to reports, scrub typhus with myocarditis is rare. The only case of scrub typhus myocarditis confirmed by endomyocardial biopsy was reported in 1991 in a Japanese adult in whom heart failure occurred 3 mo after acute febrile illness[18]. Third, the first Weil-Felix test for our patient was negative. There are several effective laboratory methods to diagnose scrub typhus, such as enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), immunofluorescence assay (IFA), immunochromatographic test, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), the Weil-Felix test, and loop-mediated isothermal amplification. The PCR detection method has the highest sensitivity and specificity and is especially suitable for patients with eschar of unknown origin and fever but lacks applicability due to the diverse serotypes of Orientia tsutsugamushi and its expense. Immuno-based detection methods such as IFA and ELISA also have a high sensitivity and specificity, but the positivity rate is low in early stages; thus, repeated sampling is required to increase the diagnosis rate[19]. The principle of the Weil-Felix test is that the serum of patients with scrub typhus can agglutinate with the Proteus Oxk strain, and a single result of serum Oxk ≥ 1:160 has diagnostic significance. The rate of Weil-Felix test positivity was only 30% in the first week, 60% in the second week, and 80%-90% in the third week. Fortunately, emergency surgery ruled out primary abdominal infection; the patient had a history of jungle activities leading to the correct antibiotic regimen, including doxycycline, and the patient was finally cured and discharged.

Through this case and literature review, the experience is summarized as follows: (1) Over one-third of patients with scrub typhus present with gastrointestinal symptoms, such as bloating, abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting. In severe cases, the disease can manifest as diffuse peritonitis and even perforation of the digestive tract[14]. In addition, scrub typhus with pancreatitis is rarely reported, but its appearance may indicate critical illness and a higher mortality rate[15]. Therefore, in endemic areas, differential diagnosis of patients with abdominal pain and peritonitis should consider scrub typhus; (2) Eschar is key for the diagnosis of scrub typhus, with a detection rate of 46%-86%[7]. The eschar of scrub typhus is usually accompanied by swollen lymph nodes, and hence examining in detail swollen lymph nodes can increase the discovery rate of eschars. Immuno-based detection methods have low positive rates at early stages; among them, the positivity rate for the Weil-Felix test in the first week of the course of scrub typhus is approximately 30%. For suspicious cases, the Weil-Felix test needs to be repeated. IFA and ELISA should be implemented for higher sensitivity and specificity. Furthermore, PCR may be the best diagnostic method for patients without eschar; and (3) Scrub typhus is a multisystem-damaging disease (especially in patients with a course of more than 1 wk), and the clinical manifestations are complex and diverse. Clinicians should become further informed. Overall, it is urgent to disseminate knowledge about scrub typhus.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Infectious diseases

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Marickar F S-Editor: Wu YXJ L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Xing YX

| 1. | Tamura A, Ohashi N, Urakami H, Miyamura S. Classification of Rickettsia tsutsugamushi in a new genus, Orientia gen. nov., as Orientia tsutsugamushi comb. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1995;45:589-591. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 250] [Cited by in RCA: 228] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Liu YX, Feng D, Suo JJ, Xing YB, Liu G, Liu LH, Xiao HJ, Jia N, Gao Y, Yang H, Zuo SQ, Zhang PH, Zhao ZT, Min JS, Feng PT, Ma SB, Liang S, Cao WC. Clinical characteristics of the autumn-winter type scrub typhus cases in south of Shandong province, northern China. BMC Infect Dis. 2009;9:82. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Rodkvamtook W, Gaywee J, Kanjanavanit S, Ruangareerate T, Richards AL, Sangjun N, Jeamwattanalert P, Sirisopana N. Scrub typhus outbreak, northern Thailand, 2006-2007. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:774-777. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Goswami D, Hing A, Das A, Lyngdoh M. Scrub typhus complicated by acute respiratory distress syndrome and acute liver failure: a case report from Northeast India. Int J Infect Dis. 2013;17:e644-e645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rapmund G. Rickettsial diseases of the Far East: new perspectives. J Infect Dis. 1984;149:330-338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Silpapojakul K. Scrub typhus in the Western Pacific region. Ann Acad Med Singap. 1997;26:794-800. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Kim DM, Won KJ, Park CY, Yu KD, Kim HS, Yang TY, Lee JH, Kim HK, Song HJ, Lee SH, Shin H. Distribution of eschars on the body of scrub typhus patients: a prospective study. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;76:806-809. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zhang M, Zhao ZT, Wang XJ, Li Z, Ding L, Ding SJ. Scrub typhus: surveillance, clinical profile and diagnostic issues in Shandong, China. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;87:1099-1104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Tsay RW, Chang FY. Serious complications in scrub typhus. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 1998;31:240-244. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Chanta C, Chanta S. Clinical study of 20 children with scrub typhus at Chiang Rai Regional Hospital. J Med Assoc Thai. 2005;88:1867-1872. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Rajapakse S, Rodrigo C, Fernando D. Scrub typhus: pathophysiology, clinical manifestations and prognosis. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2012;5:261-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Chrispal A, Boorugu H, Gopinath KG, Prakash JA, Chandy S, Abraham OC, Abraham AM, Thomas K. Scrub typhus: an unrecognized threat in South India - clinical profile and predictors of mortality. Trop Doct. 2010;40:129-133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 67] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Jamil M, Bhattacharya P, Mishra J, Akhtar H, Roy A. Eschar in Scrub Typhus: A Study from North East India. J Assoc Physicians India. 2019;67:38-40. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Lee CH, Lee JH, Yoon KJ, Hwang JH, Lee CS. Peritonitis in patients with scrub typhus. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;86:1046-1048. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Ahmed AS, Paul Prabhakar A, Sathyendra S, Abraham O. Acute pancreatitis due to scrub typhus. Journal of Global Infectious Diseases. 2014;6:31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Praveen Kumar A, Prasad A, Gumpeny L, Siddappa R. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis and polyarthralgia in scrub typhus: An unusual presentation. Int J Med Public Health. 2013;3:352. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Moron CG, Popov VL, Feng HM, Wear D, Walker DH. Identification of the target cells of Orientia tsutsugamushi in human cases of scrub typhus. Mod Pathol. 2001;14:752-759. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 129] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Yotsukura M, Aoki N, Fukuzumi N, Ishikawa K. Review of a case of tsutsugamushi disease showing myocarditis and confirmation of Rickettsia by endomyocardial biopsy. Jpn Circ J. 1991;55:149-153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kala D, Gupta S, Nagraik R, Verma V, Thakur A, Kaushal A. Diagnosis of scrub typhus: recent advancements and challenges. 3 Biotech. 2020;10:396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |