Published online Aug 16, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i23.6886

Peer-review started: April 17, 2021

First decision: May 10, 2021

Revised: May 12, 2021

Accepted: June 25, 2021

Article in press: June 25, 2021

Published online: August 16, 2021

Processing time: 109 Days and 23.4 Hours

Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common type of malignant lymphoma (ML), accounting for 30%-40% of cases of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) in adults. Primary paranasal sinus lymphoma is a rare presentation of extranodal NHL that accounts for only 0.17% of all lymphomas. ML from the maxillary sinus (MS) is a particularly rare presentation, and is thus often difficult to diagnose. We have reported the first known case of DLBCL originating from the MS with rapidly occurrent multiple skin metastasis.

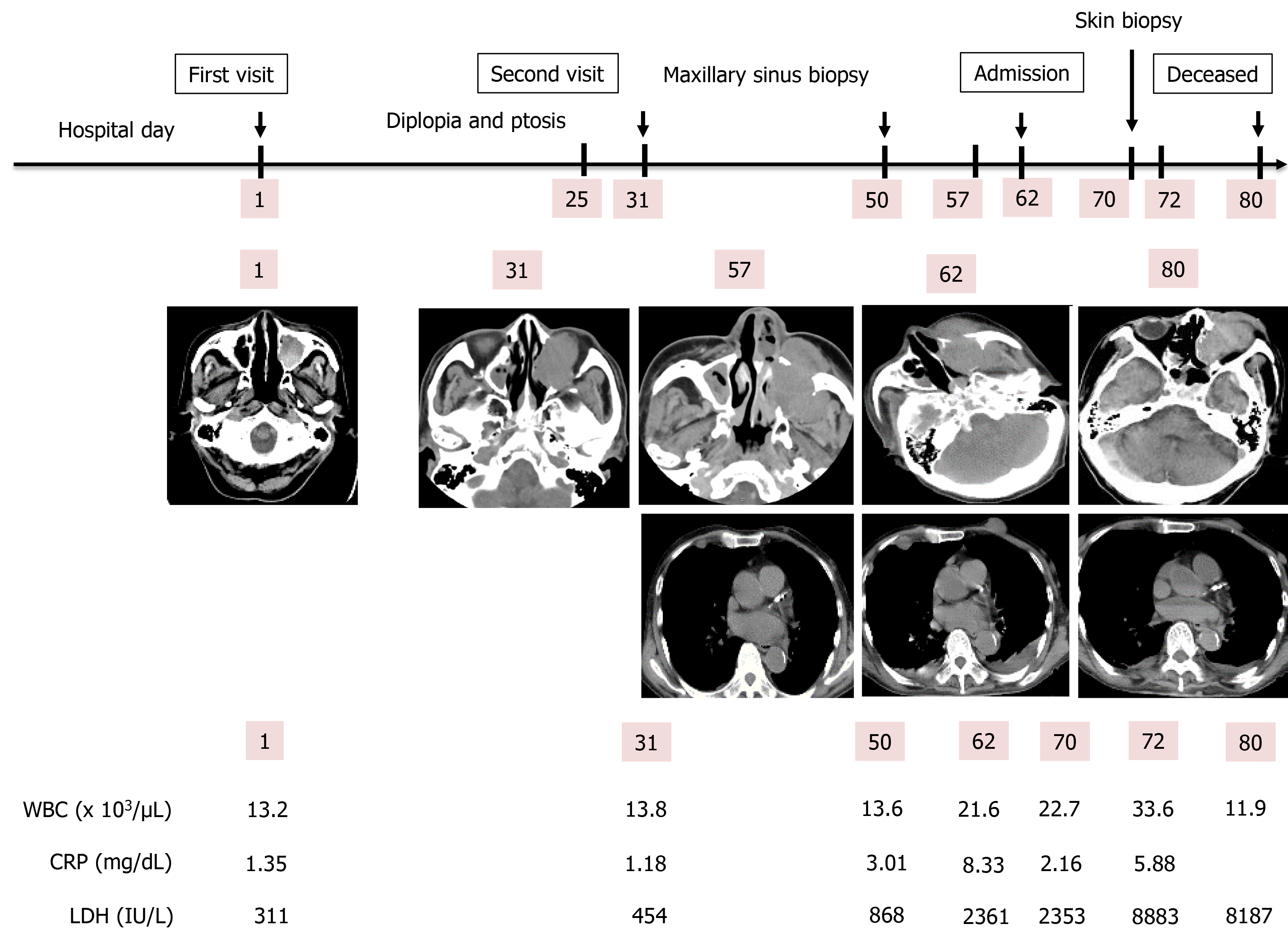

An 81-year-old Japanese man visited our hospital due to continuous pain for 12 d in the left maxillary nerve area. His medical history included splenectomy due to a traffic injury, an old right cerebral infarction from when he was 74-years-old, hypertension, and type 2 diabetes mellitus. A plain head computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a 3 cm × 3.1 cm × 3 cm sized left MS. On day 25, left diplopia and ptosis occurred, and a follow-up CT on day 31 revealed the growth of the left MS mass. Based on an MS biopsy on day 50, we established a definitive diagnosis of DLBCL, non-germinal center B-cell-like originating from the left MS. The patient was admitted on day 62 due to rapid deterioration of his condition, and a plain CT scan revealed the further growth of the left MS mass, as well as multiple systemic metastasis, including of the skin. A skin biopsy on day 70 was found to be the same as that of the left MS mass. We notified the patient and his family of the disease, and they opted for palliative care, considering on his condition and age. The patient died on day 80.

This case suggests the need for careful, detailed examination, and for careful follow-up, when encountering patients presenting with a mass.

Core Tip: Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) is the most common type of malignant lymphoma (ML), accounting for 30%-40% of cases of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) in adults. Primary paranasal sinus lymphoma is a rare presentation of extranodal NHL that accounts for only 0.17% of all lymphomas. ML from the maxillary sinus (MS) is rarely encountered as a presentation, and is thus often difficult to diagnose. We have reported the first known case of DLBCL originating from the MS with rapidly occurrent multiple skin metastases; this case suggests that there is a need for careful, detailed examination, and careful follow-up, when encountering patients presenting with a mass.

- Citation: Usuda D, Izumida T, Terada N, Sangen R, Higashikawa T, Sekiguchi S, Tanaka R, Suzuki M, Hotchi Y, Shimozawa S, Tokunaga S, Osugi I, Katou R, Ito S, Asako S, Takagi Y, Mishima K, Kondo A, Mizuno K, Takami H, Komatsu T, Oba J, Nomura T, Sugita M, Kasamaki Y. Diffuse large B cell lymphoma originating from the maxillary sinus with skin metastases: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(23): 6886-6899

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i23/6886.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i23.6886

Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) refers to a category of neoplasms originating in lymphoreticular system cells; these malignancies are extremely diverse, and frequently tend to affect organs and tissues that would ordinarily contain no lymphoid cells[1,2]. Some 40% of NHL cases develop in extranodal sites, and the stomach, liver, soft tissue, dura, bone, intestine, and bone marrow are among the most common primary extranodal lymphoma sites[1]. However, primary NHL has been found to rarely affect the nasal cavities or the paranasal sinuses[1].

The most common variety of malignant lymphoma (ML) originating from the germinal center is diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), which accounts for some 30%-40% of adult NHL cases worldwide. This group of diseases is heterogeneous, with variable outcomes that are differentially characterized through clinical features, cell of origin (COO), molecular features, and, of late, frequently recurring mutations[3-8]. One particular type of NHL, primary paranasal sinus lymphoma (PPSL), is a rare presentation of extranodal NHL: It accounts for just 0.17% of all lymphomas, and has a distinct natural history unlike other lymphomas, and can frequently be difficult to diagnose[3,9]. This rare presentation of lymphoma is typified by bulky local tumors; ML of the maxillary sinus (MS) is likewise very rare, but it is also the most common site of origin for PPSL[3,10-16]. In one study of DLBCL originating from the sinonasal tract, a significant difference (P < 0.01) was found in the age at time of diagnosis between men (65.3-years-old) and women (71.1-years-old)[17]. In addition, the most common DLBCL primary sites were the MS (36.1%) and the nasal cavity (34.5%), with the nasal cavity being more common as a primary site in Asian/Pacific Islander patients (43.4%), and the MS being more common in patients of Caucasian (36.3%) and African (42.1%) descent[17]. Primary immunodeficiency diseases, a group of uncommon gene defects with various manifestations, demonstrate a high risk of malignancy[13]. It is extremely rare for DLBCL metastasize to the skin: there have been only known two case reports, with one originating from the lungs and the other from the testis[4,18].

To date, there have not been any reports of DLBCL originating from the MS with skin metastasis; therefore, we have reported the first such case, together with a brief review of the literature.

An 81-year-old Japanese man visited our hospital due to pain in the left maxillary nerve area (We defined the day of this visit as day 1).

The symptom had first occurred 12 d prior, and it was continuous, prickly, and persistent. He tried to keep the affected part cooled, but the symptom did not improve. On the other hand, he had no recent loss of appetite or body weight, nor night sweats.

The patient’s medical history included a splenectomy due to traffic injury, an old right cerebral infarction from when he was 74-years-old, hypertension, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and constipation. He was given 15 mg of mosapride, 75 mg of clopidogrel, 20 mg of esomeprazole magnesium, 4 mg of benidipine, 5 mg of linagliptin, 1500 mg of metformin, and 24 µg of lubiprostone on a regular basis.

The patient had no history of smoking or drinking alcohol. He did not undergo regular medical exams. The patient had previously been a carpenter, but was no longer employed. He had no food or drug allergies. He did not need any assistance for everyday life activities. He had a family of six, and presented no family history of malignant disease.

The patient was 165 cm tall and weighed 60 kg. His vital signs were normal, with blood pressure of 137/82 mmHg, heart rate of 75 regular beats/min, body temperature of 36.1 °C, oxygen saturation of 98% in ambient air, and respiratory rate of 16/min; his Glasgow Coma Scale score was 15 points (E4V5M6). Nothing else abnormal was detected upon physical examination, including skin or neurological findings.

A routine laboratory examination revealed increased values for white blood cells, proportions of monocyte and basophil, calcium, lactate dehydrogenase, plasma glucose, glycated hemoglobin, C-reactive protein, erythropoietin, immunoglobulin G, immunoglobulin A, fibrinogen, d-dimer and decreased values of red blood cells, hemoglobin, hematocrit, proportion of neutrophil, lymphocyte, eosinophil, platelets, sodium, albumin, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, zinc, thyroid stimulating hormone, free triiodothyronine, and free thyroxine. On the other hand, other tests had normal results, including biochemistry, urine qualitative and sediment, and two fecal occult blood tests (Table 1).

| Parameter (Units) | Measured value | Normal value |

| White blood cell (103/µL) | 13.2 | 3.8-8.5 |

| Neu (%) | 30 | 48-61 |

| Lym (%) | 13 | 25-45 |

| Mon (%) | 54 | 4-7 |

| Eos (%) | 0 | 1-5 |

| Bas (%) | 3 | 0-1 |

| Blast (%) | (-) | (-) |

| Red blood cell (106/µL) | 2.67 | 3.78-4.97 |

| Hemoglobin | 8.7 | 13.7-17.4 |

| Hematocrit | 26.4 | 40.2-51.5 |

| Platelet (103/µL) | 113 | 131-365 |

| Aspartate transaminase (IU/L) | 28 | 12-31 |

| Alanine aminotransferase (IU/L) | 13 | 8-40 |

| Lactic acid dehydrogenase (IU/L) | 311 | 110-210 |

| Alkaline phosphatase (IU/L) | 294 | 100-330 |

| Gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (IU/L) | 34 | 9-49 |

| Total bilirubin (mg/dL) | 0.38 | 0.3-1.2 |

| Total protein (g/dL) | 6.8 | 6.7-8.3 |

| Albumin (g/dL) | 3.3 | 3.9-4.9 |

| Creatine phosphokinase (IU/L) | 61 | 65-275 |

| Blood urea nitrogen (mg/dL) | 13.1 | 8-22 |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.77 | 0.4-0.8 |

| Amylase (IU/L) | 84 | 39-134 |

| Sodium (mEq/L) | 137 | 138-146 |

| Potassium (mEq/L) | 4.1 | 3.6-4.9 |

| Chloride (mEq/L) | 101 | 99-109 |

| Calcium (mg/dL) | 11.9 | 7.1-10.1 |

| C-reactive protein (mg/dL) | 1.35 | 0-0.4 |

| Plasma glucose (mg/dL) | 156 | 70-109 |

| Glycated Hemoglobin (NGSP) (%) | 7.8 | 4.6-6.2 |

| Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (mg/dL) | 78 | 66-141 |

| High-density lipoprotein cholesterol (mg/dL) | 26 | 41-95 |

| Triglyceride (mg/dL) | 109 | 30-150 |

| Serum iron (μg/dL) | 74 | 60-200 |

| Total iron-binding capacity (μg/dL) | 337 | 250-355 |

| Unsaturated iron binding capacity (μg/dL) | 263 | 130-320 |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 137.7 | 21-282 |

| Copper (MCG/DL) | 143 | 66-130 |

| Erythropoietin (mIU/mL) | 35.7 | 4.2-23.7 |

| Haptoglobin (mg/dL) | 104 | 19-170 |

| Zinc (μg/dL) | 71 | 80-130 |

| Folic acid (ng/mL) | 7.3 | 4 |

| Vitamin B12 (pg/mL) | 625 | 233-914 |

| Thyroid stimulating hormone (μIU/mL) | 0.025 | 0.541-4.261 |

| Free triiodothyronine (pg/mL) | 1.89 | 2.39-4.06 |

| Free thyroxine (ng/mL) | 0.53 | 0.72-1.52 |

| IgG (mg/dL) | 1857 | 870-1700 |

| IgA (mg/dL) | 438 | 110-410 |

| IgM (mg/dL) | 65 | 35-220 |

| APTT (Seconds) | 35.7 | 26.1-35.6 |

| PT (INR) | 1 | 0.8-1.18 |

| Fibrinogen (mg/dL) | 426 | 200-400 |

| D-dimer (μg/mL) | 1.28 | 0-1 |

| CH50 (U/mL) | 54 | 30-45 |

| Antinuclear antibody (Times) | < 40 | < 40 |

| Free light chain κ/λ ratio | 1.51 | 0.26-1.65 |

| Urine qualitative/sediment | Normal | Normal |

| Fecal occult blood-1 | (-) | (-) |

| Fecal occult blood-2 | (-) | (-) |

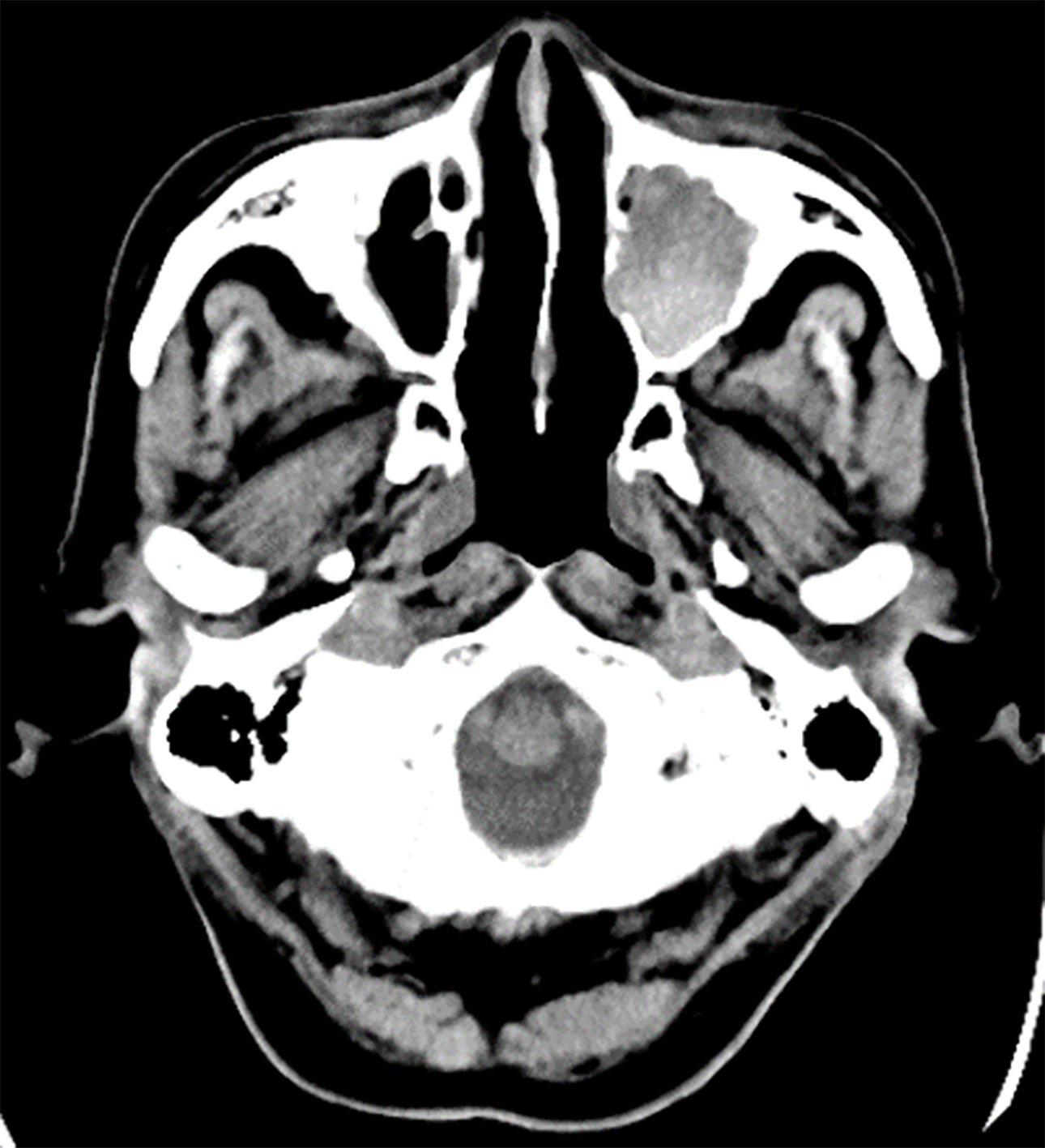

A plain head computed tomography (CT) scan revealed a 3 cm × 3.1 cm × 3 cm sized left MS in the patient, completely filled with mass, with a partially high-density area confirmed inside (Figure 1).

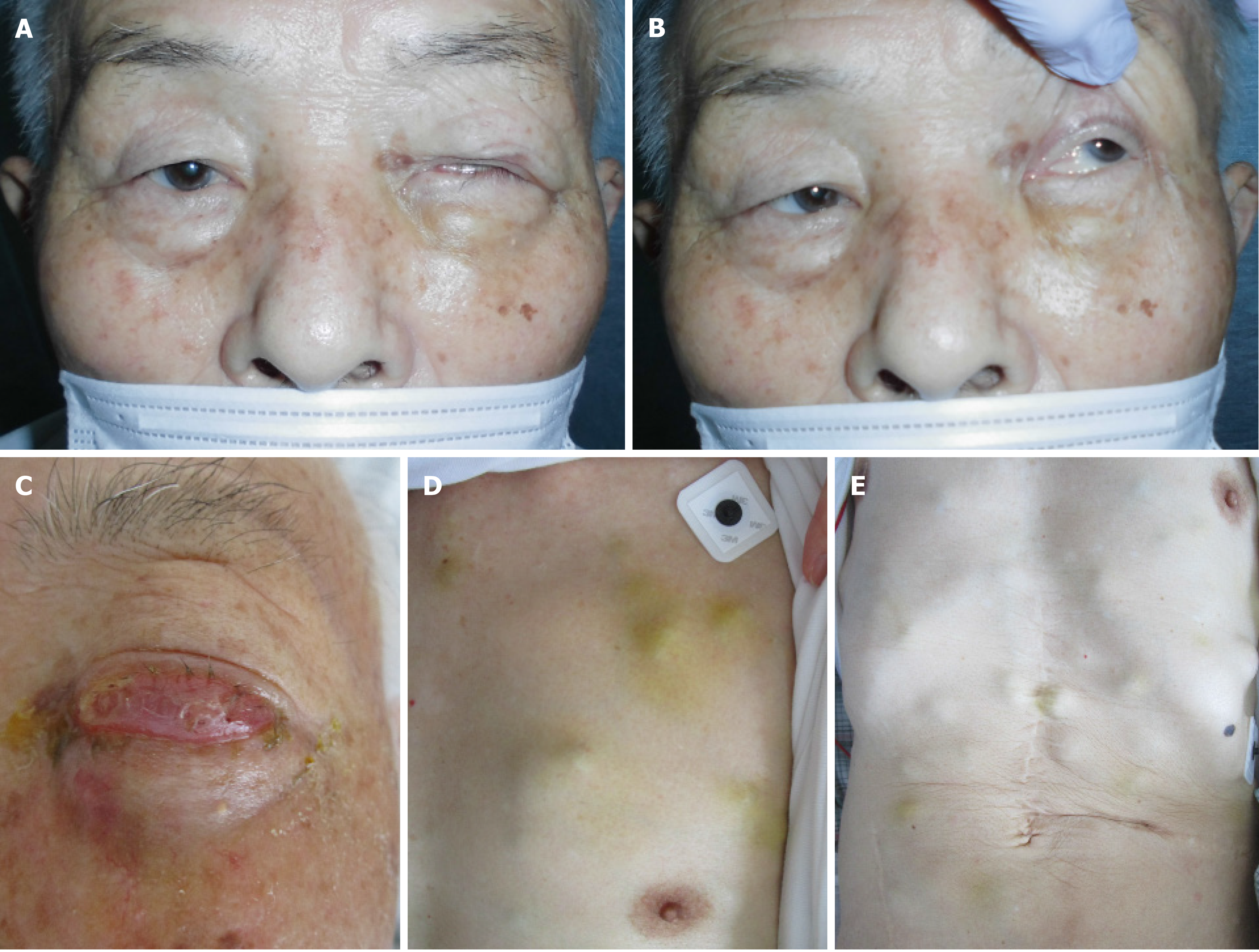

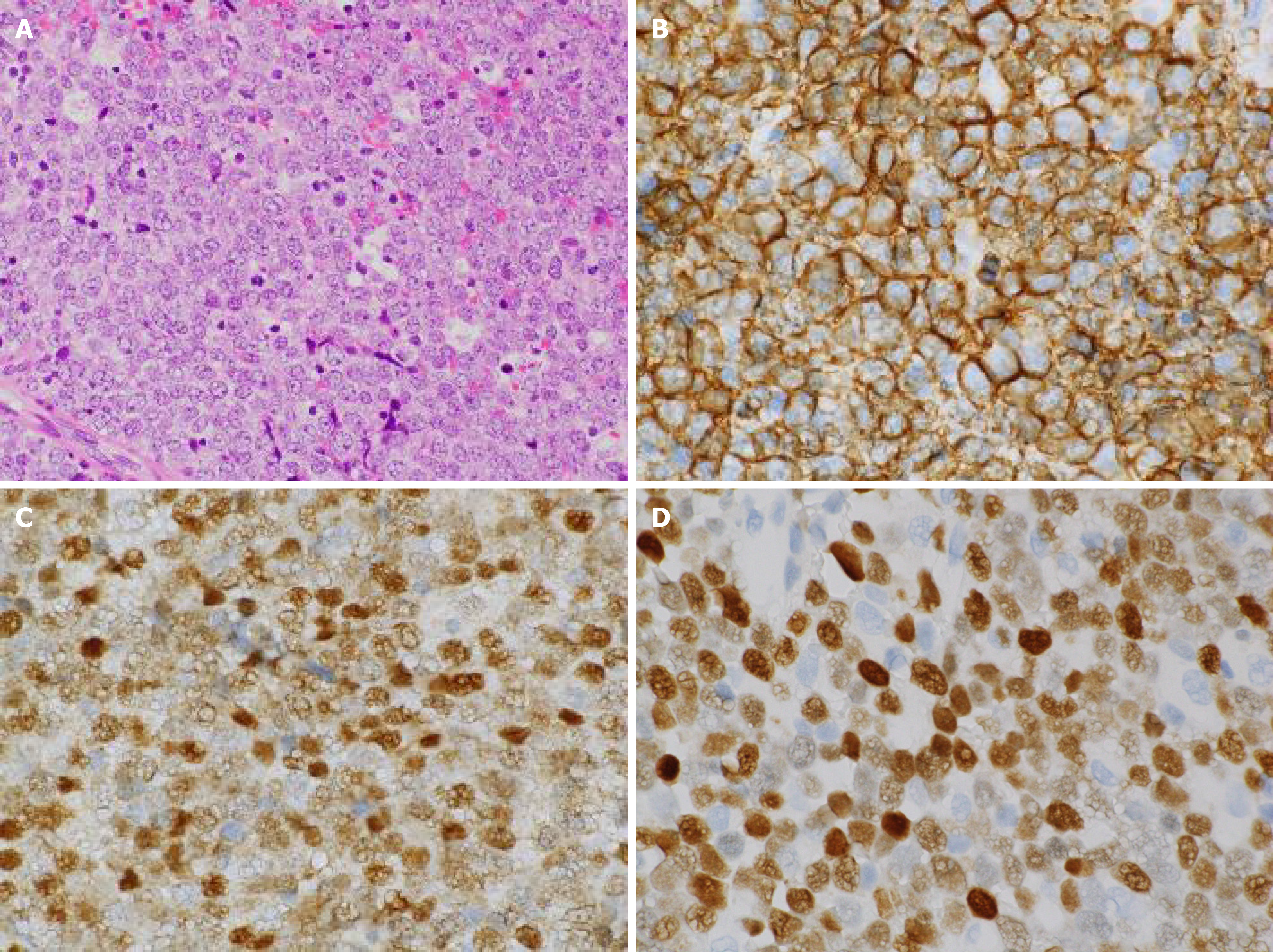

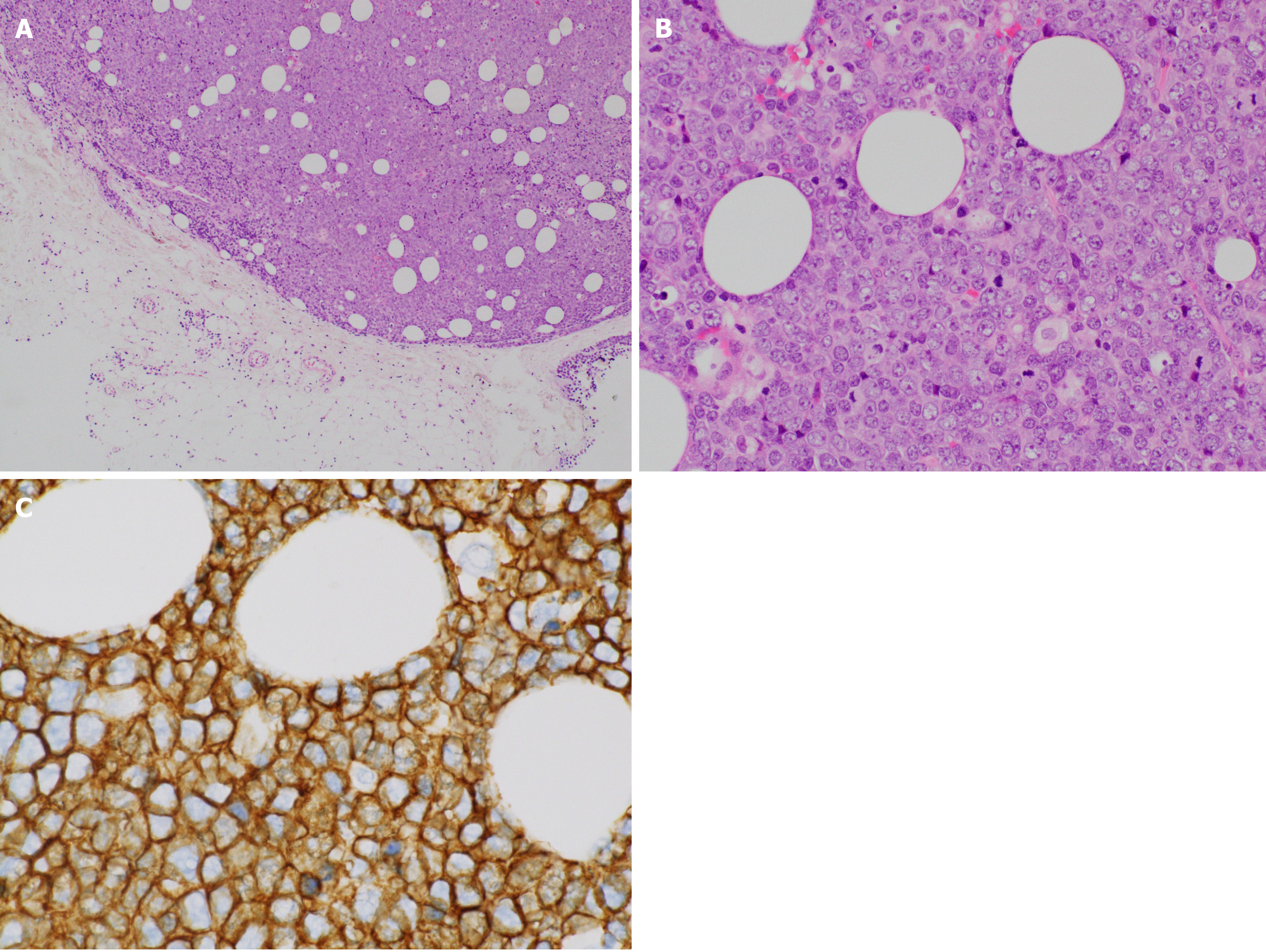

The patient was referred to an otolaryngologist. At this point, the otolaryngologist suspected a diagnosis of malignant melanoma. On the other hand, she also considered a biopsy under general anesthesia to be very risky due to the patient’s advanced age. Therefore, she made an appointment for a follow-up CT 2 mo later. Following this, left diplopia and ptosis occurred on day 25, and they persisted, so the patient visited our hospital on day 31. A physical examination confirmed left ptosis (Figure 2A). Additionally, when we opened his eyes passively, hyperexophoria of the left eye was confirmed (Figure 2B). A follow-up CT performed on the same day revealed the growth of the left MS mass, together with oppression and involvement of the orbital base, and the destruction of the anterior, internal, and external walls. An MS biopsy was performed on day 50, after a 7-d washout period. The hematoxylin and eosin stain pathological findings revealed the following: (1) Aggregates of large, atypical lymphocytes with irregular nuclei with uneven chromatin, and small to large nucleoli evident in a necrotic background; (2) Some cells showed multilobulated nuclei; and (3) Mitosis and apoptotic bodies were conspicuous (Figure 3A). Immunohistochemical staining revealed positive results for cluster of differentiation (CD) 20-positive cells, bcl-6-positive cells, and MUM1-positive cells (Figures 3B-D, respectively). It also revealed negative results for the T cell markers CD3, CD7, and CD45RO. A genetic test was not performed. Here, we excluded the possibility for T cell origin, as well as for the sinus/nasal origin, and established a definitive diagnosis of DLBCL, non-germinal center B-cell-like (GCB) originating from the left MS.

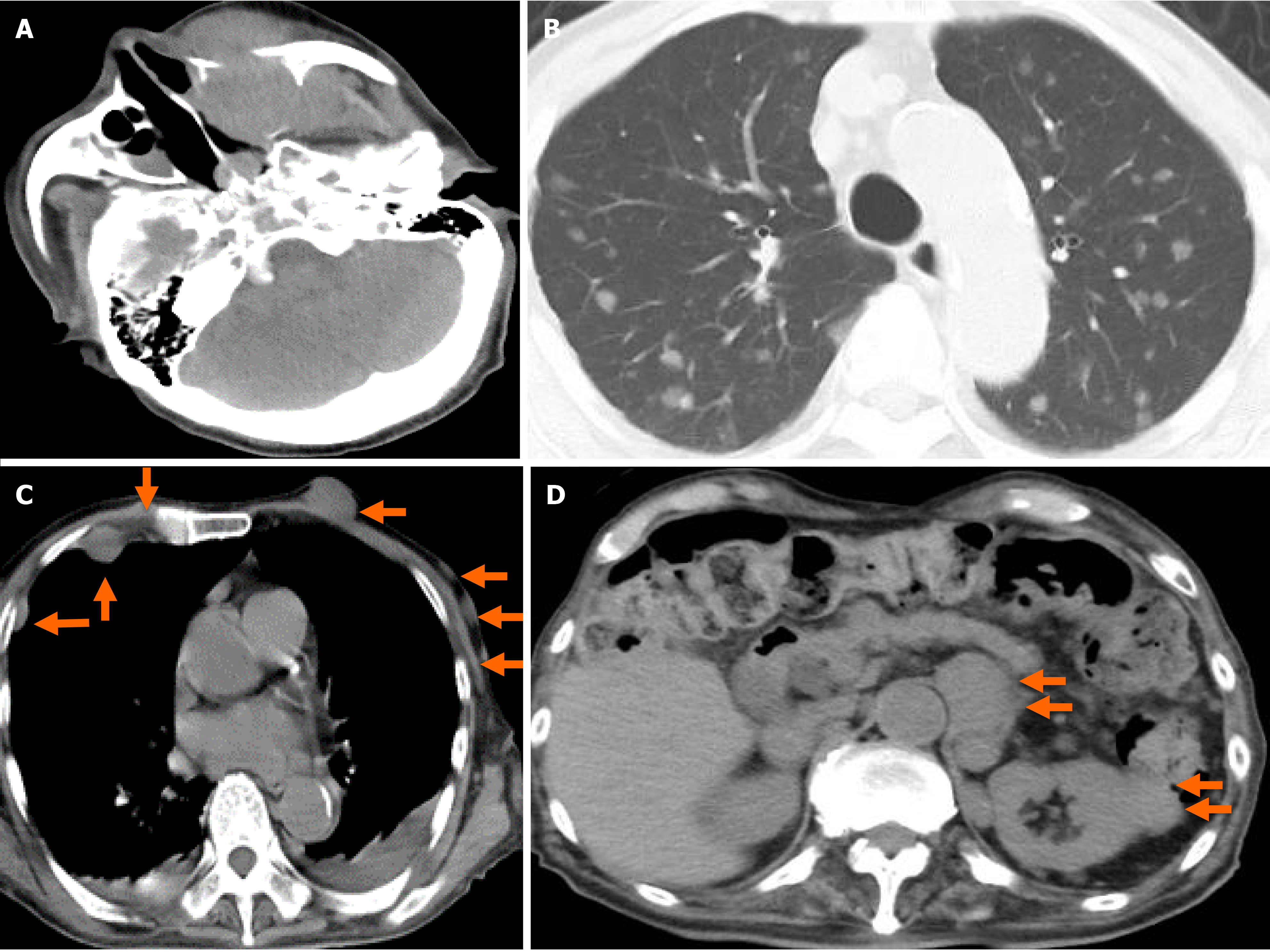

We prepared systemic chemotherapy with rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP), but the patient was admitted on day 62 due to rapid deterioration of his condition. During the physical examination, he could not open his left eye due to the circumocular swelling (Figure 2C). In addition, multiple skin tumors were confirmed on the chest and abdomen of the patient (Figure 2D and E, respectively). A plain CT scan revealed the following: Growth of the left MS mass, together with oppression and involvement of the orbital base, destruction of the anterior, internal, and external walls, and protuberance outside (Figure 4A); multiple tumors (0.5-1.5 cm in size) in both lungs (Figure 4B); multiple subcutaneous tumors and chest wall tumors (Figure 4C); abdominal paraaortic lymph node swelling (3 cm in size) and left kidney nodule (1-2 cm in size) (Figure 4D). He was referred to a dermatologist on the same day, and a skin biopsy was later performed on day 70. The histopathological images of the biopsy specimen from the skin mass were found to be the same as those of the left MS mass (Figures 5A-C). The measured value of the soluble interleukin-2 receptor on day 77 was 8063 U/mL, and BRAFV600E mutation was negative.

We established a definitive diagnosis of DLBCL, non-GCB, originating from the left MS, with rapidly occurrent multiple skin, left kidney, and abdominal paraaortic lymph node metastasis.

We notified the patient and his family of the disease, and they opted for palliative care, considering his condition and age.

The patient died on day 80. An autopsy CT was performed to confirm the cause of death, and it revealed the same findings as on day 62. However, the tumors on the skin had decreased in size. The clinical course of the patient is shown in Figure 6.

We have presented the first known case of DLBCL originating from the MS with rapidly occurrent multiple skin metastases. Another interesting finding was that the tumor progressed very rapidly, disseminating to the patient’s entire body, including the skin, and the patient died only 3 mo after the first appearance of symptoms. This type of rapidly progressive DLBCL case is very rare, and there is value in reporting this event.

DLBCL is remarkably heterogeneous at the clinical, genetic, and molecular levels, and the heterogeneous subtypes it contains have a variety of molecular dysregulations at the genetic, protein, and microRNA levels[6,19]. The clinical presentation of the patient is a particularly important feature, as it can help serve to differentiate inflammatory processes or other etiologies from neoplastic processes in the bones[20]. For DLBCL originating from the MS, the most common presenting symptoms are a mildly painful swelling of the unilateral maxilla, nasal obstruction, stuffiness, pain, mucopurulent rhinorrhea, recurrent epistaxis, diplopia, and rapidly enlarging masses, often with both local and systemic symptoms (such as fever, recurrent night sweats, or weight loss)[1,11,13,21,22]. Other, less commonly reported symptoms include palatal ulcer, chronic periodontal abscess, and persistent toothache[23,24]. Additionally, according to a radiographic imaging study of DLBCL originating from the MS, common findings included a discrete mass (59%), sinus opacification (53%), and/or bony erosion (35%)[11]. Regarding symptoms and CT findings, our case is comparable to DLBCL originating from the MS. On the other hand, we should have included soluble interleukin-2 receptor as a routine laboratory examination on first visit, and repeated that examination. Had we done so, we might have reached the DLBCL diagnosis and started treatment without delay.

DLBCL can be divided into GCB and non-GCB phenotypes, based on CD10, bcl-6, and MUM1 gene expression[19,25,26]. Because the Hans algorithm is highly concordant with the results of gene expression profiling, DLBCL is divided into GCB and non-GCB groups, based on the Hans algorithm[8]. The non-GCB/activated B cell-like subtype demonstrates frequent progression compared to the GCB subtype, despite standard immunochemotherapy[5,6].

Accurate COO-based staging should be incorporated into bone marrow (BM) examinations for DLBCL[27]. In addition, any organ may potentially be involved; ideally, DLBCL is diagnosed through an excisional biopsy of a suspicious lymph node, which will show sheets of large cells disrupting the integrity of the underlying follicle center structure, and will stain positive for CD20, CD79a, and other pan-B-cell antigens[4,5]. COO is found through histopathology and immunohistochemical stains, while molecular features such as double- or triple-hit diseases are found using fluorescent in situ hybridization analysis[5]. DLBCL’s immunophenotype classification has a close relationship to local lymph node metastasis, and has been found to possess prognostic significance. Immunophenotype classification has also proven useful for chemoth

Though timely diagnosis is critical, misdiagnoses of this disease as being more common reactive or inflammatory lesions, such as infections, are not unusual, with the majority of patients (68%) having an advanced tumor at the time of diagnosis (stage IV of the Ann Arbor classification)[20-23,29]. Likewise, in this case, by the time of the definitive diagnosis, the patient was already at stage IV of the Ann Arbor classification - a reminder of the vital importance of timely diagnoses.

DLBCL is an aggressive lymphoma that should receive prompt immunochemotherapy; spontaneous tumor regression in patients is seen only rarely before treatment is initiated[30]. The mainstay of DLBCL treatment should continue to be combination chemoradiation, though other situational treatment options include monotherapy using chemotherapy or radiotherapy[11,17]. The overwhelming majority of localized disease patients can be cured using combined modality therapy or combination chemotherapy on its own[1]. Approximately 50% of patients can be cured using doxorubicin-based combination chemotherapy and rituximab[1]. Rituximab has been found to significantly improve patient survival of DLBCL, especially for non-GCB subtype patients[31,32]. Regarding this last point, in this case, it might have been worth trying systemic chemotherapy, including rituximab, as a treatment to improve the patient’s condition, as well as his prognosis.

According to a recent study, a new potential treatment option for non-GCB DLBCL, with the synergistic antitumor effect of oridonin and the PI3K/ mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitor NVP-BEZ235 was found to show promise, though the underlying mechanism may be multifunctional, involving apoptosis, threonine kinase/mTOR and NF-kB inactivation, and reactive oxygen species-mediated deoxyribonucleic acid damage response[33]. In addition, the Hans algorithm could be regarded as a theragnostic biomarker for the section of young DLBCL patients who could benefit from an immunochemotherapy regimen of intensified dose-intensive rituximab, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vindesine, bleomycin, and prednisone (also known as “R-ACVBP”)[34]. On the other hand a regimen of rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and prednisone with bortezomib (also known as “VR-CAP”) was not seen to demonstrate improved efficacy compared to R-CHOP in non-GCB DLBCL[35].

The prognosis is variable[13]. It is crucial to pay early attention to the patient’s manifestation, select suitable treatment, and monitor manifestations[13]. Despite large advances in DLBCL treatment, approximately one patient in three has been found to progress or die, suggesting that there may also be other oncogenic events[36]. One study found a 5-year survival rate of 80%, suggesting a relatively positive prognosis for primary lymphoma of the MS[16]. The use of chemotherapy and radiotherapy have been found to significantly improve patient survival, whereas there is a significant association between Ann Arbor staging and comparatively poor outcomes[3,17]. On the other hand, one case report of DLBCL that developed in the left MS states that it relapsed as a left frontal brain mass after the disease was in remission for 4 years; this indicates the need to carefully perform long-term follow-up, even in the event of a complete remission[14].

Clinical DLBCL prognostic systems, such as the rituximab international prognostic index (IPI), age-adjusted IPI, and National Comprehensive Cancer Network IPI, use clinical factors to stratify patient risk; however, treatment approach is not affected by this[5]. IPI serves as an independent prognosticator for patients with DLBCL, and significant survival improvements were seen with the addition of rituximab[36]. In general, prognoses are relatively poor for non-GCB DLBCL, and it has been reported that there is a difference between the prognostic significances for GCB and non-GCB DLBCL[25,27]. In one study, the non-GCB type served as an independent predictor of both progression-free survival (P < 0.004) and overall survival (P = 0.042), whereas the GCB type was not found to serve as a prognostic factor independent of IPI score[27]. Using the COO of BM involvement for further prognostication can be a useful progression-free survival indicator, independent of IPI score[27]. Patients with c-myc-altered disease on its own, as well as in combination with bcl2 and/or bcl6 translocations (particularly when immunoglobulin serves as the myc translocation partner), have been found to demonstrate a poor response to up-front chemoimmunotherapy and salvage autologous stem cell transplant in the event of a relapse[5].

One novel finding regarded programmed cell death-ligand 1 (PD-L1), a member of the B7 family (also known as B7-H1) that serves as an inhibitory ligand, which is expressed on the surfaces of macrophages, dendritic cells, fibroblasts, and T cells[7]. It has been found to be more commonly expressed in the non-GCB subtype than in the GCB subtype, and there is a negative correlation between its expression in a tumor microenvironment and c-myc. Additionally, PD-L1 positivity predicts short DLBCL patient survival[7]. Therefore, strategies such as anti-PD-L1 antibody treatment should be recommended more often for patients found to have PD-L1 expression[7]. Another novel finding was that NF-κB/p65 expression has prognostic value for cases of high-risk non-GCB DLBCL, and it is considered a target suited to new therapy development[37]. Cases of non-GCB DLBCL that have negative FOXP3 are associated with favorable DLBCL prognostic parameters[8]. Serum neuron-specific enolase level may serve as an independent prognostic factor for non-GCB subtype patients; it may additionally serve as a novel disease aggressiveness marker and as a prognostic factor for non-GCB DLBCL in the era of rituximab[38]. A high Ki-67 Labeling index is considered a poor OS risk factor in the late-elderly age group and in non-GCB DLBCL patients treated with R-CHOP[32,39].

Finally, this case led to the interesting autopsy CT finding that the skin tumors had decreased in size. Related to this phenomenon, there is a report of a case of sponta

This case study has several limitations: this article only reviews a single case report and case series of DLBCL originating from the MS. Therefore, the actual situation and nature of the disease may differ from the results of our literature review, as a result of reporting bias. In addition, it was a primary lymphoma in the nasal sinus, and this patient had prior splenectomy, therefore we should have considered post splenectomy secondary malignancies. In a previous report, splenectomized patients had an increased risk of being hospitalized for hematologic malignancies including of NHL, Hodgkin lymphoma, multiple myeloma, acute myeloid leukemia, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, chronic myeloid leukemia, and any leukemia (rate ratios = 1.8-6.0). They also had an increased risk of death due to any cancer including of NHL, Hodgkin lymphoma, and any leukemia (rate ratios = 1.3-4.7). These observed risks were increased more than 10 years after splenectomy. On the other hand, we could not get information of histology about the removed spleen.

We have presented the first case of DCBCL originating from the MS with multiple rapidly occurrent skin metastases. This case suggests the need for careful, detailed examinations when encountering patients presenting with a mass: When a neoplastic lesion is confirmed through image inspection, we should investigate thoroughly, including further image investigations and pathologic examination. Careful follow-up is also necessary.

We thank Dr. Sohsuke Yamada for pathological diagnosis for this case.

| 1. | Adwani DG, Arora RS, Bhattacharya A, Bhagat B. Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of maxillary sinus: An unusual presentation. Ann Maxillofac Surg. 2013;3:95-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Nadendla LK, Meduri V, Paramkusam G. Imaging characteristics of diffuse large cell extra nodal non-Hodgkin's lymphoma involving the palate and maxillary sinus: a case report. Imaging Sci Dent. 2012;42:111-114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Su ZY, Zhang DS, Zhu MQ, Shi YX, Jiang WQ. [Primary non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the paranasal sinuses: a report of 14 cases]. Ai Zheng. 2007;26:919-922. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Latif Moini A, Farbod Ara T, Fazeli Mosleh Abadi M. Primary pulmonary lymphoma and cutaneous metastasis: a case report. Iran J Radiol. 2014;11:e15574. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Liu Y, Barta SK. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: 2019 update on diagnosis, risk stratification, and treatment. Am J Hematol. 2019;94:604-616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 338] [Article Influence: 48.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Yang JM, Jang JY, Jeon YK, Paik JH. Clinicopathologic implication of microRNA-197 in diffuse large B cell lymphoma. J Transl Med. 2018;16:162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Hu LY, Xu XL, Rao HL, Chen J, Lai RC, Huang HQ, Jiang WQ, Lin TY, Xia ZJ, Cai QQ. Expression and clinical value of programmed cell death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) in diffuse large B cell lymphoma: a retrospective study. Chin J Cancer. 2017;36:94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Serag El-Dien MM, Abdou AG, Asaad NY, Abd El-Wahed MM, Kora MAEM. Intratumoral FOXP3+ Regulatory T Cells in Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2017;25:534-542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Catalfamo L, Nava C, Matyasova J, De Ponte FS. Primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the ethmoido-orbital region. J Craniofac Surg. 2013;24:e602-e604. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lee H, Choi KE, Park M, Lee SH, Baek S. Primary diffuse large B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma of the paranasal sinuses presenting as cavernous sinus syndrome. J Craniofac Surg. 2014;25:e338-e339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Peng KA, Kita AE, Suh JD, Bhuta SM, Wang MB. Sinonasal lymphoma: case series and review of the literature. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2014;4:670-674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Shan Y, Cui J, Zheng J. [One case of primary malignant lymphoma of the maxillary sinus]. Lin Chung Er Bi Yan Hou Tou Jing Wai Ke Za Zhi. 2014;28:137-138. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Ashrafi F, Klein C, Poorpooneh M, Sherkat R, Khoshnevisan R. A case report of sinusoidal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in a STK4 deficient patient. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99:e18601. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kewan T, Awada H, Covut F, Haddad A, Daw H. Late Central Nervous System Relapse in a Patient with Maxillary Sinus Lymphoma. Cureus. 2018;10:e3745. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Nakamura K, Uehara S, Omagari J, Kunitake N, Jingu K, Masuda K. Primary non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the maxillary sinus. Am J Clin Oncol. 1997;20:272-275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Varelas AN, Eggerstedt M, Ganti A, Tajudeen BA. Epidemiologic, prognostic, and treatment factors in sinonasal diffuse large B -cell lymphoma. Laryngoscope. 2019;129:1259-1264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Goel S, Sachdev R, Mohapatra I, Gajendra S, Gupta S. Unusually Aggressive Primary Testicular Diffuse Large B Cell Lymphoma with Post Therapy Extensive Metastasis. J Clin Diagn Res. 2016;10:ED01-ED02. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Guo Y, Takeuchi I, Karnan S, Miyata T, Ohshima K, Seto M. Array-comparative genomic hybridization profiling of immunohistochemical subgroups of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma shows distinct genomic alterations. Cancer Sci. 2014;105:481-489. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Chain JR, Kingdom TT. Non-Hodgkin's lymphoma of the frontal sinus presenting as osteomyelitis. Am J Otolaryngol. 2007;28:42-45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Lombard M, Michel G, Rives P, Moreau A, Espitalier F, Malard O. Extranodal non-Hodgkin lymphoma of the sinonasal cavities: A 22-case report. Eur Ann Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Dis. 2015;132:271-274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | O'Connor RM, Vasey M, Smith JC. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the maxillary sinus. Ear Nose Throat J. 2010;89:E8-10. [PubMed] |

| 22. | Janardhanan M, Suresh R, Savithri V, Veeraraghavan R. Extranodal diffuse large B cell lymphoma of maxillary sinus presenting as a palatal ulcer. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Yoon JH, Chun YC, Park SY, Yook JI, Yang WI, Lee SJ, Kim J. Malignant lymphoma of the maxillary sinus manifesting as a persistent toothache. J Endod. 2001;27:800-802. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Toda H, Sato Y, Takata K, Orita Y, Asano N, Yoshino T. Clinicopathologic analysis of localized nasal/paranasal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. PLoS One. 2013;8:e57677. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Zhang Z, Shen Y, Shen D, Ni X. Immunophenotype classification and therapeutic outcomes of Chinese primary gastrointestinal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. BMC Gastroenterol. 2012;12:77. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Cho MC, Chung Y, Jang S, Park CJ, Chi HS, Huh J, Suh C, Shim H. Prognostic impact of germinal center B-cell-like and non-germinal center B-cell-like subtypes of bone marrow involvement in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with R-CHOP. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e13046. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Kim HS. Primary testicular diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: A case report focusing on touch imprint cytology and a non-germinal center B-cell-like phenotype. Exp Ther Med. 2013;6:33-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | de Castro MS, Ribeiro CM, de Carli ML, Pereira AAC, Sperandio FF, de Almeida OP, Hanemann JAC. Fatal primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the maxillary sinus initially treated as an infectious disease in an elderly patient: A clinicopathologic report. Gerodontology. 2018;35:59-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Buckner TW, Dunphy C, Fedoriw YD, van Deventer HW, Foster MC, Richards KL, Park SI. Complete spontaneous remission of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the maxillary sinus after concurrent infections. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2012;12:455-458. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Leonard JP, Kolibaba KS, Reeves JA, Tulpule A, Flinn IW, Kolevska T, Robles R, Flowers CR, Collins R, DiBella NJ, Papish SW, Venugopal P, Horodner A, Tabatabai A, Hajdenberg J, Park J, Neuwirth R, Mulligan G, Suryanarayan K, Esseltine DL, de Vos S. Randomized Phase II Study of R-CHOP With or Without Bortezomib in Previously Untreated Patients With Non-Germinal Center B-Cell-Like Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35:3538-3546. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 140] [Article Influence: 15.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Li ZM, Huang JJ, Xia Y, Zhu YJ, Zhao W, Wei WX, Jiang WQ, Lin TY, Huang HQ, Guan ZZ. High Ki-67 expression in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma patients with non-germinal center subtype indicates limited survival benefit from R-CHOP therapy. Eur J Haematol. 2012;88:510-517. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Qing K, Jin Z, Fu W, Wang W, Liu Z, Li X, Xu Z, Li J. Synergistic effect of oridonin and a PI3K/mTOR inhibitor on the non-germinal center B cell-like subtype of diffuse large B cell lymphoma. J Hematol Oncol. 2016;9:72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Molina TJ, Canioni D, Copie-Bergman C, Recher C, Brière J, Haioun C, Berger F, Fermé C, Copin MC, Casasnovas O, Thieblemont C, Petrella T, Leroy K, Salles G, Fabiani B, Morschauser F, Mounier N, Coiffier B, Jardin F, Gaulard P, Jais JP, Tilly H. Young patients with non-germinal center B-cell-like diffuse large B-cell lymphoma benefit from intensified chemotherapy with ACVBP plus rituximab compared with CHOP plus rituximab: analysis of data from the Groupe d'Etudes des Lymphomes de l'Adulte/Lymphoma study association phase III trial LNH 03-2B. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32:3996-4003. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 60] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Offner F, Samoilova O, Osmanov E, Eom HS, Topp MS, Raposo J, Pavlov V, Ricci D, Chaturvedi S, Zhu E, van de Velde H, Enny C, Rizo A, Ferhanoglu B. Frontline rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, and prednisone with bortezomib (VR-CAP) or vincristine (R-CHOP) for non-GCB DLBCL. Blood. 2015;126:1893-1901. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Jovanovic MP, Mihaljevic B, Jakovic L, Martinovic VC, Fekete MD, Andjelic B, Antic D, Bogdanovic A, Boricic N, Terzic T, Jelicic J, Milenkovic S. BCL2 positive and BCL6 negative diffuse large B cell lymphoma patients benefit from R-CHOP therapy irrespective of germinal and non germinal center B cell like subtypes. J BUON. 2015;20:820-828. [PubMed] |

| 36. | Wang J, Zhou M, Zhang QG, Xu J, Lin T, Zhou RF, Li J, Yang YG, Chen B, Ouyang J. Prognostic value of expression of nuclear factor kappa-B/p65 in non-GCB DLBCL patients. Oncotarget. 2017;8:9708-9716. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Wang L, Liu P, Chen X, Geng Q, Lu Y. Serum neuron-specific enolase is correlated with clinical outcome of patients with non-germinal center B cell-like subtype of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with rituximab-based immunochemotherapy. Med Oncol. 2012;29:2153-2158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Koh YW, Hwang HS, Park CS, Yoon DH, Suh C, Huh J. Prognostic effect of Ki-67 expression in rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and prednisone-treated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is limited to non-germinal center B-cell-like subtype in late-elderly patients. Leuk Lymphoma. 2015;56:2630-2636. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Apte RS, Al-Abdulla NA, Green WR, Schachat AP, DeJong MR, DiBernardo C, Handa JT. Systemic non-Hodgkin B-cell lymphoma encountered as a vanishing choroidal mass. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:105-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Kristinsson SY, Gridley G, Hoover RN, Check D, Landgren O. Long-term risks after splenectomy among 8,149 cancer-free American veterans: a cohort study with up to 27 years follow-up. Haematologica. 2014;99:392-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 251] [Article Influence: 19.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Hematology

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Huang AHC, Viswanath Y, Wang XJ, Yi XL S-Editor: Zhang L L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Xing YX