Published online Jun 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i18.4803

Peer-review started: January 15, 2021

First decision: March 27, 2021

Revised: April 7, 2021

Accepted: May 6, 2021

Article in press: May 6, 2021

Published online: June 26, 2021

Processing time: 147 Days and 8.6 Hours

Cutaneous myiasis is frequently observed; however, eosinophilic pleural effusion induced by this condition is rare.

We report the case of a 65-year-old female Tibetan patient from Qinghai Province, who presented to West China Hospital of Sichuan University around mid-November 2011 with a chief complaint of recurrent cough, occasional hemoptysis, and right chest pain. There was no past medical and surgical history of note, except for occasional dietary habit of eating raw meat. Clinical examination revealed a left lung collapse and diminished breathing sounds in her left lung, with moist rales heard in both lungs. Chest X-rays demonstrated a left hydropneumothorax and a right lung infection. Chest computed tomography revealed a left hydropneumothorax with partial compressive atelectasis and patchy consolidation on the right lung. Laboratory data revealed peripheral blood eosinophilia of 37.2%, with a white blood cell count of 10.4 × 109/L. Serum immunoglobulin E levels were elevated (1650 unit/mL). Serum parasite antibodies were negative except for cysticercosis immunoglobulin G. Bone marrow aspirates were hypercellular, with a marked increase in the number of mature eosinophils and eosinophilic myelocytes. An ultrasound-guided left-sided thoracentesis produced a yellow-cloudy exudative fluid. Failure to respond to antibiotic treatment during hospitalization for her symptoms and persistent blood eosinophilia led the team to start oral albendazole (400 mg/d) for presumed parasitic infestation for three consecutive days after the ninth day of hospitalization. Intermittent migratory stabbing pain and swelling sensation on both her upper arms and shoulders were reported; tender nodules and worm-like live organisms were observed in the responding sites 1 wk later. After the removal of the live organisms, they were subsequently identified as first stage hypodermal larvae by the Sichuan Institute of Parasites. The patient’s symptoms were relieved soon afterwards. Telephonic follow-up 1 mo later indicated that the blood eosinophilia and pleural effusion were resolved.

Eosinophilic pleural fluid can be present in a wide array of disorders. Myiasis should be an important consideration for the differential diagnosis when eosinophilic pleural effusion with blood eosinophilia is observed.

Core Tip: Eosinophilic pleural fluid can be present in a wide array of disorders. This condition generally occurs in patients due to the presence of air or blood in the pleural space or infections, or when patients are in a hypersensitive state or during malignancy. Myiasis should be an important consideration for the differential diagnosis when eosinophilic pleural effusion with blood eosinophilia is observed.

- Citation: Fan T, Zhang Y, Lv Y, Chang J, Bauer BA, Yang J, Wang CW. Cutaneous myiasis with eosinophilic pleural effusion: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(18): 4803-4809

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i18/4803.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i18.4803

Eosinophilic pleural effusion is defined as cytology of pleural fluid containing at least 10% eosinophils[1]. The incidence of eosinophilic pleural effusion is estimated to be 9% of all pleural effusions[2]. This condition generally occurs in patients due to the presence of air or blood in the pleural space or infections, or when patients are in a hypersensitive state or during malignancy[2,3].

Parasitic infestations have been reported to induce eosinophilic pleural effusion in humans, typically with concomitant parenchymal disease[4]. The most frequent parasite associated with this condition is paragonimus species; however, cutaneous myasis, sparganosis, toxocariasis, and amebiasis have also been identified as etiologic agents[4,5].

Herein, we present a rare case of eosinophilic pleural effusion induced by cutaneous myiasis.

Recurrent cough and right chest pain.

A 65-year-old Tibetan woman from Qinghai Province was admitted to West China Hospital of Sichuan University around mid-November 2011. Three months prior to hospitalization, she was suspected of having pneumonia with mild cough and occasional hemoptysis. Her primary care physician prescribed oral penicillin; however, her symptoms were not completely resolved. One week prior to admission, the patient underwent a chest X-ray in Yushu Municipal Hospital for aggravated right chest pain. Chest X-rays demonstrated a left hydropneumothorax and a right lung infection. She was referred to our hospital for further evaluation and treatment.

She did not have a history of surgery, trauma, or infectious disease.

The patient was a housewife who had been living in the Tibetan area and never traveled to outside provinces. She had been healthy until August 2011. She admitted to eating raw meat occasionally as it was a dietary habit in Tibetan culture.

On admission, the patients’ blood pressure was 115/65 mmHg, heart rate was 73 beats/min, respiratory rate was 20/min, and her body temperature was 36.5 °C. Physical examination revealed a left lung collapse and diminished breathing sounds in her left lung, with moist rales heard in both lungs. No rash or nodules were observed on the skin or mucosa.

Laboratory data revealed peripheral blood eosinophilia of 37.2%, with a white blood cell count of 10.4 × 109/L. Red blood cell counts, hemoglobin, platelet counts, and serum levels of aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, and urea nitrogen levels are shown in Table 1. Creatinine levels were normal. A nonspecific increase in cancer antigen 125, neuron-specific enolase, immunoglobulin G (IgG), and IgA was observed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay and/or serum electrophoresis. Serum IgE levels were elevated (1650 unit/mL). Serum parasite antibodies were negative except for cysticercosis IgG. No ova or parasites were observed in stool samples. Bone marrow aspirates were hypercellular, with a marked increase in the number of mature eosinophils and eosinophilic myelocytes. An ultrasound-guided left-sided thoracentesis produced a yellow-cloudy exudative fluid. The fluid had eosinophil predominance with no evidence of malignancy or parasites on analysis. Gram staining, acid-fast staining, and fungal smears indicated the absence of organisms.

| Blood | Value |

| WBC, × 109/L | 10.44 |

| NEUTs, % | 38.6 |

| EO, % | 37.2 |

| RBC, × 1012/L | 5.44 |

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 156 |

| PLT, × 109/L | 181 |

| TP, g/L | 53.1 |

| ALB, g/L | 34.9 |

| AST, IU/L | 42 |

| ALT, IU/L | 40 |

| ALP, IU/L | 94 |

| Urea nitrogen, mmol/L | 3.2 |

| Creatinine, μmol/L | 59 |

| CA-125, U/mL | 76.70 |

| NSE, ng/mL | 16.49 |

| IgG, g/L | 17.9 |

| IgA, mg/L | 3870 |

| IgE, IU/mL | 1650.00 |

| C3, g/L | 0.8730 |

| C4, g/L | 0.2200 |

| RF, IU/mL | < 20.00 |

| ANA | Negative |

| DNA | Negative |

| RNP | Negative |

| SM | Negative |

| SSA | Negative |

| SSB | Negative |

| SCL-70 | Negative |

| Jo-1 | Negative |

| Rib-P | Negative |

| Cysticercosis IgG | Positive |

| Schistosoma IgG | Negative |

| Clonorchis IgG | Negative |

| Echinococcus IgG | Negative |

| Pleural effusion | |

| TP, g/L | 42.6 |

| Glu, mmol/L | 0.35 |

| LDH, IU/L | 1053 |

| ADA, IU/L | 11.4 |

| Color | Yellow |

| Transparency | Cloudy |

| Nucleated cells, × 106/ L | > 20000 |

| Red cells, × 106/L | 100 |

| Pyocyte/HP | ++ |

| Multinuclear cells, % | 100 |

| Cytology | EO dominant |

| Chylus | Negative |

| TB-DNA | Negative |

| Gram stain | Negative |

| Acid-fast stain | Negative |

| Fungal smear | Negative |

| Parasites | Negative |

| Bone marrow | |

| Granulocyte% | 67.5 |

| EO% | 25.5 |

| Parasites | Negative |

| Stool | |

| Ascaris ova | Negative |

| Hookworm ova | Negative |

| Amoeba | Negative |

| Whipworm ova | Negative |

| Enterobius vermicularis ova | Negative |

| Schistosome ova | Negative |

| Cestode ova | Negative |

| Clonorchiasis sinensis ova | Negative |

| Giardia lamblia | Negative |

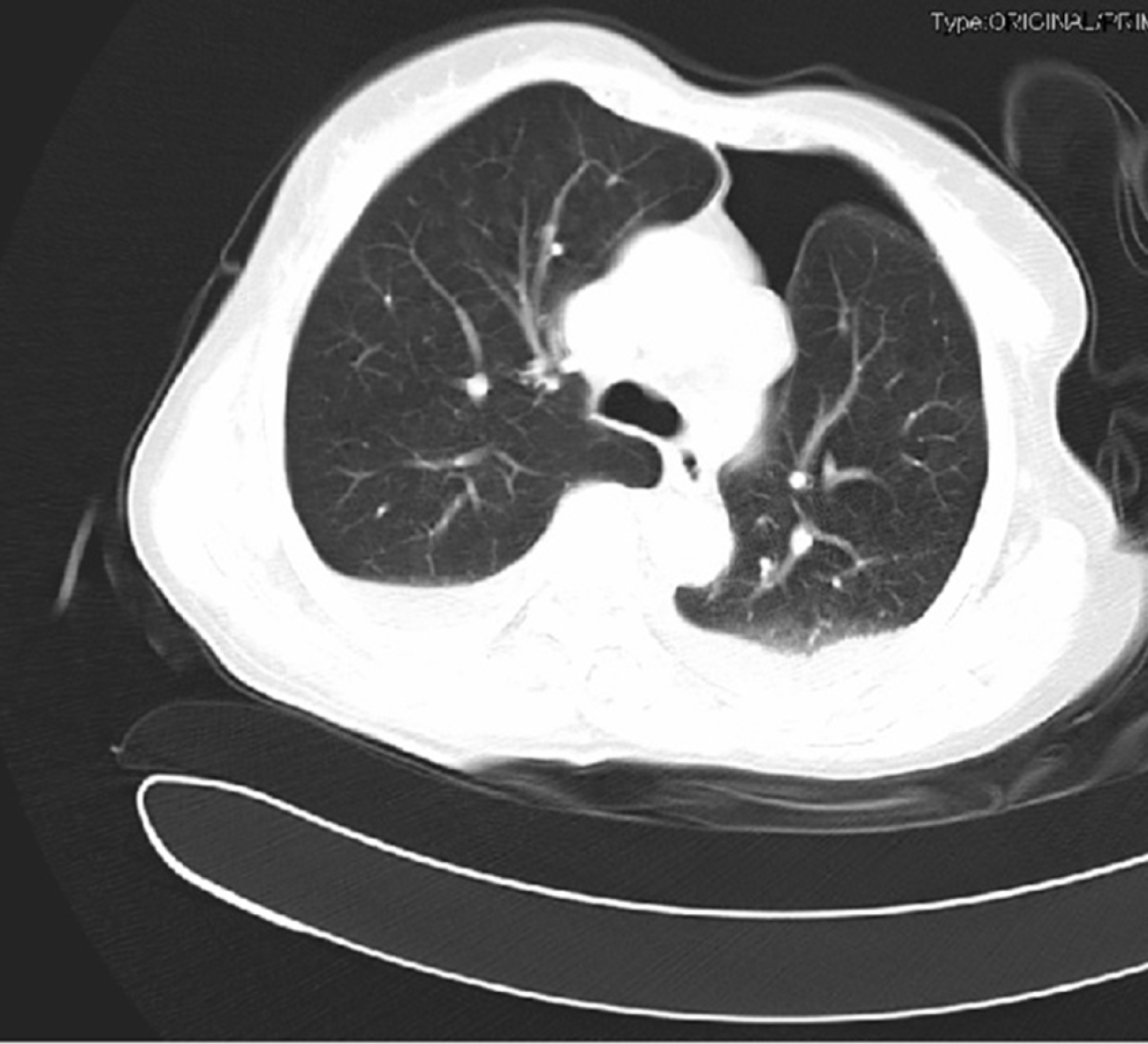

Chest computed tomography revealed a left hydropneumothorax with partial compressive atelectasis and patchy consolidation on the right lung (Figure 1).

The diagnosis of cutaneous myiasis induced by first stage Hypoderma larvae was confirmed.

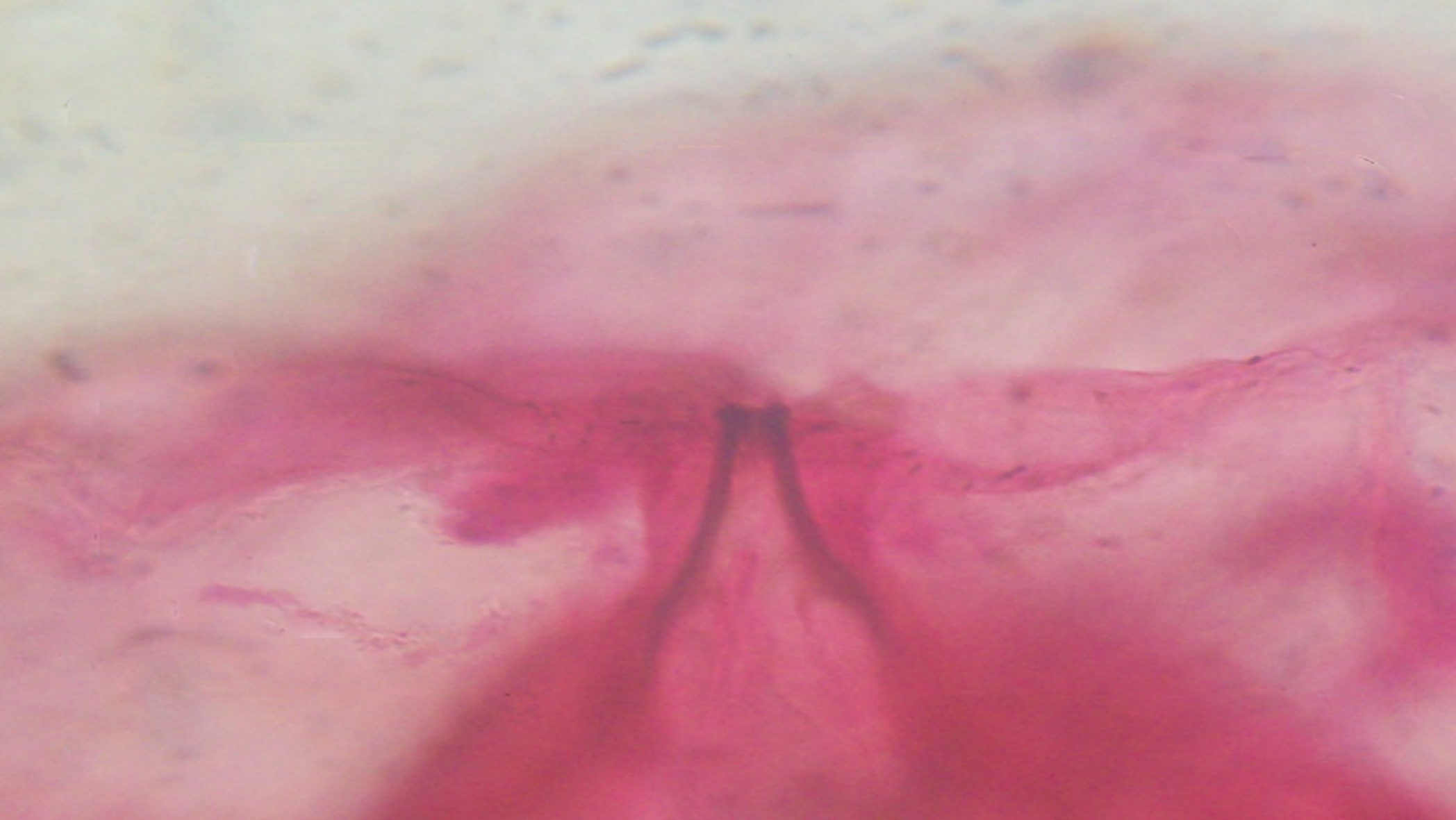

The patient had no response to antibiotic treatment during hospitalization for her symptoms and had persistent blood eosinophilia. Hence, oral albendazole (400 mg/d) was initiated empirically for presumed parasitic infestation for three consecutive days after the ninth day of hospitalization. One week later, the patient complained of intermittent migratory stabbing pain and swelling sensation on both her upper arms and shoulders. A 2 cm × 2 cm red, tender nodule was observed on her left cubital fossa. On the 17th d of hospitalization, numerous non-purulent nodules were observed on the right shoulder and left upper arm. Two worm-like live organisms were observed in the 0.1 cm × 0.1 cm warbles. They were removed by gentle pressure and transferred to 95% alcohol. They were subsequently identified as first stage hypodermal larvae by the Sichuan Institute of Parasites (Figure 2).

The patient’s symptoms gradually diminished 4 d later. She was discharged with a diagnosis of cutaneous myiasis with eosinophilic pleural effusion. Telephonic follow-up 1 mo after discharge indicated her symptoms were resolved, and she experienced a total recovery.

Myiasis is an infestation of live vertebrates by the larvae of dipterous flies. The infestation usually occurs in the host's dead or living tissue, liquid body substance, or ingested food[6]. The larvae induce inflammation or lesions and produce eosinophilia and systemic symptoms such as fever, rash, cough, and serous effusion[7]. The diverse clinical features usually lead to a misdiagnosis or delayed treatment.

The majority of myiasis occurs in tropical regions[8]. Poor hygiene, inadequate environmental sanitation, and low socioeconomic status are the most important risk factors for acquiring myiasis. In China, it is frequently observed in farming and pastoral areas such as Qinghai, Tibet, and Inner Mongolia Provinces[9], where the people are susceptible to be infected due to their close contact with domestic animals and traditional custom of consuming raw meat.

Although cutaneous myiasis frequently occurs in these regions, eosinophilic pleural effusion induced by myiasis is very rare[2]. An extensive review of the literature revealed a similar case reported in the 1980s. A 54-year-old Caucasian American male with recurrent painful migratory subcutaneous nodules associated with marked blood eosinophilia and eosinophilic pleural effusion was diagnosed with cutaneous myiasis induced by the larvae of hypodermal lineatum[4]. In addition, two additional case reports published in China regarding cutaneous myiasis with pleural effusion were both from the Tibetan regions[10,11].

The pathogenesis could be attributed to hypodermal lineatum migrating extensively and traversing the area beneath the pleura to induce an eosinophilic response. Previous studies in cattle have demonstrated that parasites migrate towards the posterior border of the ribs, while reports have been published showing that these parasites migrate towards the eye, tongue, and spinal cord in humans[12].

Early diagnosis for cutaneous myiasis is challenging and depends on the appearance of the larvae. Although clinical features, epidemiology, blood eosinophilia, and eosinophilic granuloma are used to determine the etiology, diagnosis is commonly delayed for months until the larvae appear on the skin. Next-generation sequencing strategies have made a significant difference in the early detection of infectious agents. The use of this technology may provide for the rapid identification of parasitic infections in humans[13].

Eosinophilic pleural fluid is observed in a wide array of disorders; however, certain features may provide clues to the differential diagnosis of pleural effusions. Eosinophilic pleural effusion alone is usually either idiopathic or due to chest wall trauma, pulmonary infarction, or pneumonia[5]. If an eosinophilic pleural effusion is associated with blood eosinophilia, parasitic infestation, hypersensitivity state, mycobacterial or fungal infections, vasculitis disorders, or even lymphoreticular malignancies should be initially considered. Concomitant parenchymal disease is a clue to possible parasitic infestation.

With the development of medical knowledge, the onset of myiasis has become extremely rare. However, this case report suggests that there is still a possibility of disease in farming and pastoral areas, where people are in close contact with domestic animals. Due to potential threats to both human and animal welfare and health posed by myiasis, medical care providers at all levels should be aware of this potential diagnosis. The prevention and treatment of the disease is not complicated. In general, the larvae will be discharged from the body naturally or by gentle pressure around the warble. Any secondary bacterial infections should be treated with antibiotics. Oral administration of histamine or prednisone may reduce systemic responses and blood eosinophilia. Paying attention to personal hygiene and environmental sanitation is upmost to prevent myiasis.

In summary, eosinophilic pleural effusion due to cutaneous myiasis has rarely been reported. Early diagnosis and appropriate interventions are essential. Whenever an eosinophilic pleural effusion occurs in tropical regions or in farming and pastoral areas, one should consider this to be myiasis. Good personal hygiene and environmental sanitation are upmost methods to prevent myiasis. Awareness of clinicians about the possibility of this disease may help identification of future similar cases.

We would like to thank The HEAD Foundation, Singapore for their support for Dr. Yang J and Dr. Bauer BA.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Knysz B S-Editor: Gao CC L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Li JH

| 1. | Na MJ. Diagnostic tools of pleural effusion. Tuberc Respir Dis (Seoul). 2014;76:199-210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Oba Y, Abu-Salah T. The prevalence and diagnostic significance of eosinophilic pleural effusions: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Respiration. 2012;83:198-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Krenke R, Nasilowski J, Korczynski P, Gorska K, Przybylowski T, Chazan R, Light RW. Incidence and aetiology of eosinophilic pleural effusion. Eur Respir J. 2009;34:1111-1117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Uttamchandani RB, Trigo LM, Poppiti RJ Jr, Rozen S, Ratzan KR. Eosinophilic pleural effusion in cutaneous myiasis. South Med J. 1989;82:1288-1291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kalomenidis I, Light RW. Eosinophilic pleural effusions. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2003;9:254-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Francesconi F, Lupi O. Myiasis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2012;25:79-105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 335] [Cited by in RCA: 350] [Article Influence: 25.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | El-Beshbishi SN, Ahmed NN, Mostafa SH, El-Ganainy GA. Parasitic infections and myositis. Parasitol Res. 2012;110:1-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Singh A, Singh Z. Incidence of myiasis among humans-a review. Parasitol Res. 2015;114:3183-3199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Jiang CP. [Human myiasis in China: a review of 107 cases during 1995-2002]. Zhongguo Jishengchong Xue Yu Jishengchong Bing Zazhi. 2003;21:55-56. |

| 10. | Zhang C, She JS, Zhang WQ. Cutaneous myiasis with pleural effusion as the initial manifestation: a case report. Zhongguo Yiyao Zhinan Zazhi. 2011;9:299. |

| 11. | Wei XJ, Zhang JZ. A case of cutaneous myiasis with empyema. Zhongguo Jishengchong Xue Yu Jishengchong Bing Zazhi. 2002;20:5. |

| 12. | Kalomenidis I, Light RW. Pathogenesis of the eosinophilic pleural effusions. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2004;10:289-293. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Anis E, Hawkins IK, Ilha MRS, Woldemeskel MW, Saliki JT, Wilkes RP. Evaluation of Targeted Next-Generation Sequencing for Detection of Bovine Pathogens in Clinical Samples. J Clin Microbiol. 2018;56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |