Published online Jun 26, 2021. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i18.4491

Peer-review started: January 20, 2021

First decision: February 23, 2021

Revised: March 1, 2021

Accepted: April 13, 2021

Article in press: April 13, 2021

Published online: June 26, 2021

Processing time: 142 Days and 6.5 Hours

Hepatitis C virus (HCV)/human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) coinfection is a major problem among HIV-infected patients, resulting in increased morbidity and mortality rates due to the acceleration of liver fibrosis progression by HIV, leading to liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. Although the efficacy of direct-acting antiviral therapy in patients with HIV/HCV coinfection and HCV monoinfection are similar in terms of sustained virologic response rate, there are some additional complications that arise in the treatment of patients with HIV/HCV coinfection, including drug-drug interactions and HCV reinfection due to the high risk behavior of these patients. This review will summarize the current management of HIV/HCV coinfection.

Core Tip: Hepatitis C virus (HCV) coinfection is a major cause of liver-related disease among patients with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), with higher rates of morbidity and mortality compared to HCV-monoinfected patients. Treatment with direct-acting antiviral (DAA) agents has shown good efficacy in HCV/HIV-coinfected patients and achieves sustained virologic response (SVR) rates similar to those of HCV-monoinfected patients. The appropriate selection of DAA regimen is of crucial importance, however, and drug interaction with antiretroviral therapy should be taken into account to avoid adverse outcomes and lower rates of SVR.

- Citation: Laiwatthanapaisan R, Sirinawasatien A. Current treatment for hepatitis C virus/human immunodeficiency virus coinfection in adults. World J Clin Cases 2021; 9(18): 4491-4499

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v9/i18/4491.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v9.i18.4491

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/hepatitis C virus (HCV) coinfection results in greater morbidity and mortality compared with HCV monoinfection[1]. Due to the pathophysiology of HIV and HCV coinfection, HIV accelerates the progression of liver fibrosis, leading to liver cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma[2]. HIV/HCV coinfection patients also have a higher incidence of cardiovascular disease. A meta-analysis by Osibogun et al[3] reported that HIV/HCV coinfection leads to an increased risk of cardiovascular diseases compared to HIV monoinfection, with a hazard ratio of 1.24.

HIV/HCV coinfection was more difficult to treat than HCV monoinfection before the advent of direct-acting antiviral (DAA) agents, and most studies showed lower rates of sustained virologic response (SVR) in patients with HIV/HCV coinfection who received interferon treatment. Currently, DAA shows high efficacy in attaining SVR rates that are comparable in patients with HIV/HCV coinfection and those with HCV monoinfection[4,5] as shown in Table 1. However, the drug interaction between antiretroviral therapy (ART) and DAAs still constitutes a major problem in treatment, as it may undermine the efficacy of DAAs or increase the toxicity of DDAs.

| HCV monoinfection | HCV/HIV coinfection | |

| Prevalence | 184 million person worldwide | 2.3 million person worldwide |

| SVR after interferon treatment | 36%-76% (genotype 1, 2, 3, 4, treatment naïve) | 18.4%-50% (genotype 1, 2, 3, 4, treatment naïve) |

| SVR after DAA treatment | 96%-100% (pangenotype, treatment naïve) | 95%-98% (pangenotype, treatment naïve) |

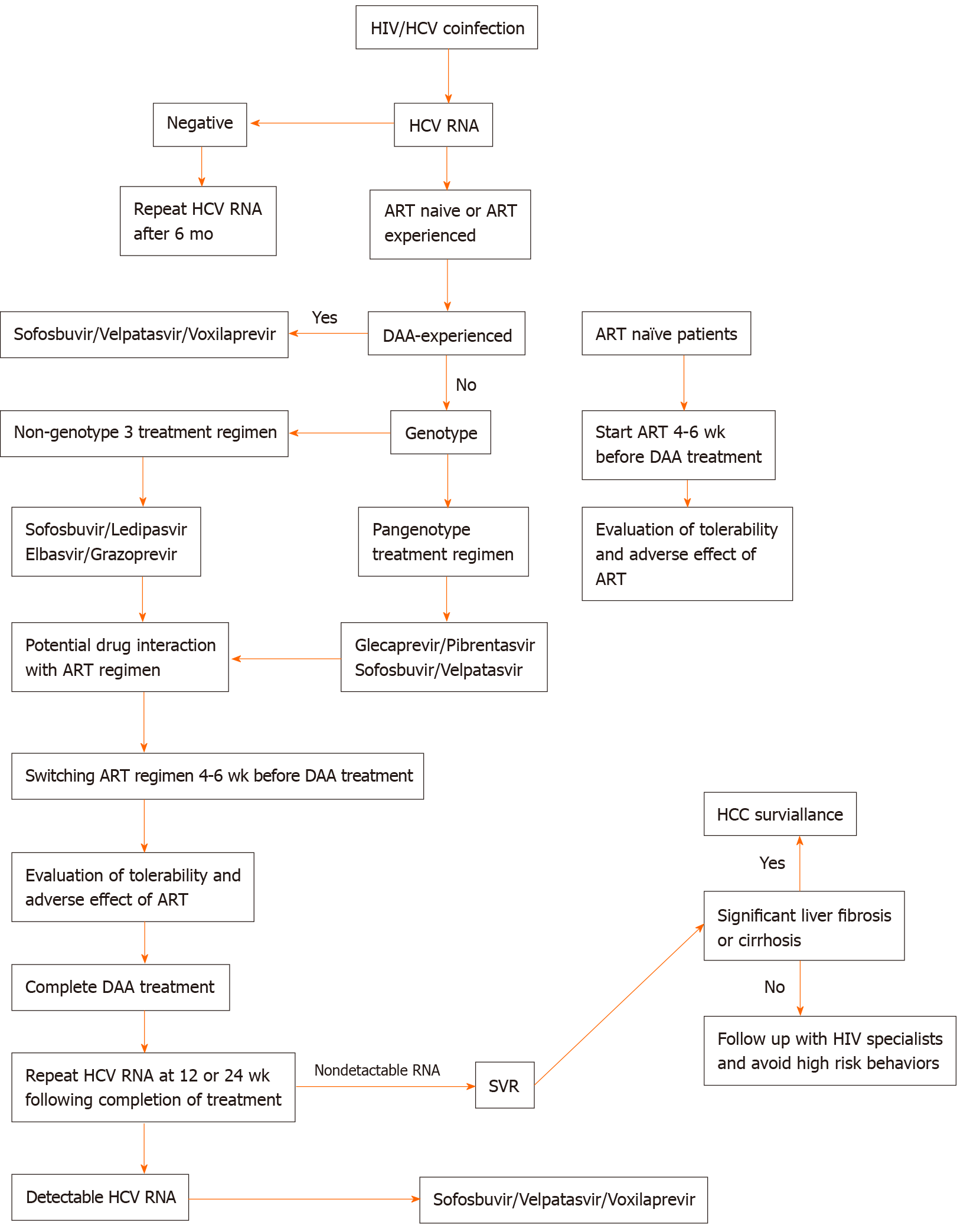

In this review, we summarize and simplify the current management of HIV/HCV coinfection (Figure 1).

The endpoint of HCV therapy is an SVR evaluated by quantitative HCV RNA and a liver function test panel at 12 or 24 wk following completion of treatment confirming the undetectability of HCV RNA and normalization of liver enzyme[6]. This cure of HCV infection determined by SVR yields several clinical benefits that can reduce the rate of liver decompensation, delay progression of liver fibrosis, reduce the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma, and also lower the HCV transmission rate among these patients.

All patients with virologic evidence of chronic HCV infection should receive DAA treatment if not prevented from doing so by financial constraints. On the other hand, in settings of limited resources, treatment should be prioritized in favor of patients who are at the highest risk of substantial morbidity and mortality from untreated HCV infection such as those with advanced fibrosis or cirrhosis, those who are transplant recipients, or those who have severe extrahepatic manifestations.

The principal of DAA regimen selection is based on genotype, HCV treatment experience, current ART regimen, and the presence of liver cirrhosis or other comorbidities that carry contraindications for certain DAA regimens. Patients with HIV/HCV coinfection have been found to be more likely to delay DAA treatment than patients with HCV monoinfection. A study by Zuckerman et al[7] revealed that patients with HIV/HCV coinfection had a longer time to initiation of DAA than HCV-monoinfected patients because of changing ART therapy. HCV-monoinfected patients started DAA treatment after a median of 13 d (IQR 8-26 d), compared to a median of 24 d (IQR 14-46 d) for those with HIV/HCV coinfection, while median time to treatment initiation in HIV/HCV coinfection patients who did not change ART regimen was 18 d. Early consultation and good coordination between HIV specialists and hepatologists could shorten the delay in DAA treatment initiation.

For patients who have never received ART, timing of DAA treatment and ART initiation are of paramount importance. It is generally recommended that ART be commenced 4-6 wk before DAA in order to evaluate the tolerability and adverse effects of ART, as some patients have to undergo changes in ART regimens that might affect the selection of DAA treatment. Evidence from a study in the interferon era showed that initiating ART treatment before HCV therapy achieved restoration of immune function and improved HCV treatment outcomes[8].

HIV/HCV coinfected patients who are tolerant to ART regimens and have good HIV suppression can start HCV treatment if no significant drug interaction occurs with the selected HCV treatment; furthermore, they can continue their original ART regimen. In the event that ART has potential drug interaction with the DAA treatment, a switch in ART regimen is indicated. While changing an ART regimen, it is important to be aware of the potential for adverse events triggered by new agents, and of the possibility of HIV viral breakthrough. HCV treatment should be delayed for 4-6 wk after switching ART regimen to allow patients to develop tolerance to the new ART regimen.

Genotype-based regimens can be divided into two groups: Non-genotype 3 and pangenotype. This simplifies regimen selection as the efficacy of HCV antiviral regimens in coinfected patients is comparable to that in monoinfected individuals, a critical factor to consider in choosing DAA regimens is potential drug interaction with the patient’s current ART (Table 2).

| Antiretroviral drugs | SOF/LED | SOF/VEL | SOF/VEL/VOX | EBR/GZR | GLE/PIB |

| NRTIs | |||||

| Tenoforvir disoproxil fumarate | ▲ | ▲ | ▲ | - | - |

| NNRTIs | |||||

| Efavarenz | - | X | X | X | X |

| Etravirenz | - | X | X | X | X |

| Nevirapine | - | X | X | X | X |

| Protease inhibitors | |||||

| Atazanavir/ritonavir | - | - | X | X | X |

| Atazanavir/cobicistat | - | - | X | X | X |

| Darunavir/ritonavir | - | - | X | X | X |

| Darunavir/cobicistat | - | - | - | X | X |

| Lopinavir/ritonavir | - | - | X | X | X |

The efficacy of sofosbuvir (SOF)/ledipasvir (LED) for the treatment of HIV/HCV coinfection patients has been evaluated in many studies, although these have mostly included genotype 1 (98%-100%) and only a small amount genotype 4 (2%) data, and they have been found to attain good SVR of up to 96%-98%[9]. Several studies of HCV monoinfection patients have shown that SOF/LED could be used in genotype 4, 5, and 6 with an SVR of up to 96.6%[10-12]. Data concerning the use of this regimen in patients with HIV/HCV genotypes 4, 5, and 6 coinfection are sparse, but a study of a small number of these coinfected patients has shown good efficacy[13].

For patients who had tenofovir disoproxil fumarate in ART treatment, caution is advisable, as this regimen increases tenofovir levels; patients with an estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) < 60 mL/min should also avoid this regimen[14]. Tenofovir alafenamide could be an alternative for concomitant use with SOF/LDV regimen in patients with impaired renal function.

The C-EDGE CO-INFECTION study, which included treatment-naive patients with HIV/HCV-genotype 1, 4, and 6 coinfection, showed that treatment efficacy with 12 wk of this regimen achieved SVR of 96%[15]. The most common side effects of this regimen were fatigue (13%), headache (12%) and nausea (9%).

The use of efavirenz and etravirine should be avoided, as they cause a decrease in levels of elbasvir and grazoprevir; in addition, protease inhibitors are contraindicated because they trigger elevated grazoprevir levels[16].

The efficacy of glecaprevir/pibrentasvir has been proven by the phase 3, multicenter EXPEDITION-2 study, which included treatment-naive and experienced HIV/HCV coinfection patients with genotype 1, 2, 3, 4, or 6 infection. An 8- or 12-wk course of the daily fixed-dose combination of glecaprevir (300 mg)/pibrentasvir (120 mg) was administered in patients without and with compensated cirrhosis respectively. This study achieved SVR12 of up to 98%[17]. Treatment for 8 wk with glecaprevir/pibrentasvir showed similar SVR rates to a 12-wk course of this regimen in HCV-monoinfected patients with cirrhosis, but data concerning HIV/HCV coinfection patients with cirrhosis are scarce. Consequently, an 8-wk course of glecaprevir/pibrentasvir cannot be recommended for HIV/HCV coinfected patients with cirrhosis at this time. The most commonly noted adverse events from this regimen were headache and fatigue.

Glecaprevir/pibrentasvir should not be used with atazanavir owing to the risk of aminotransferase elevation[18], and other protease inhibitors, including darunavir, lopinavir, and ritonavir, are contraindicated because they increase levels of glecaprevir/pibrentasvir. In addition, patients who are on ART containing efavirenz, etravirine or nevirapine, should not be prescribed glecaprevir/pibrentasvir because of potential reductions in plasma glecaprevir/pibrentasvir levels.

The ASTRAL-5 trial, which evaluated the efficacy of sofosbuvir/velpatasvir for 12 wk in patients with HIV/HCV coinfected patients included genotype 1, 2, 3, and 4, managed to achieve SVR12 of up to 95%[19]. The most common adverse events of this regimen were headache, fatigue and nausea.

Sofosbuvir/velpatasvir should not be used with nevirapine, efavirenz or etravirine because these agents can reduce velpatasvir levels due to their enzymatic inducer capability[20].

This regimen is recommended for patients in whom previous DAA treatment has failed, although only limited data exist regarding the use of these regimens in HIV/HCV coinfected patients. The RESOLVE study[21], which evaluated the treatment efficacy of this regimen in coinfected patients with previous DAA treatment failure, revealed SVR12 of 82%; however, the small sample size of only 18 patients means that further research involving a larger number of patients is needed. Headache, diarrhea and nausea were the most commonly reported adverse events.

Sofosbuvir/velpatasvir/voxilaprevir are not recommended for use with enzyme inducer medications, such as efavirenz, etravirine, and nevirapine, because of the risk of a decline in DAA drug levels. Voxilaprevir should not be used with ritonavir-boosted atazanavir, as it increases voxilaprevir levels by up to 331%.

Some HIV/HCV coinfection patients also have HBV infection because these diseases share the same modes of transmission. The principle of ART is the same as that for patients with HBV/HIV coinfection, which is to choose antiretroviral agents with activity against HBV[22], and the drug of choice could be tenofovir disoproxil fumarate or tenofovir alafenamide. It is important to be aware of the potential for HBV reactivation during DAA treatment in patients who are not on antivirals which act against HBV. Usually, HCV has mechanisms to suppress HBV replication, but if HCV is removed during DAA treatment, HBV flare can occur[23]. In patients with only anti-HBc positive with hepatitis B surface antigen-negative status, an antiviral agent against HBV is not required, but ALT should be monitored monthly to identify HBV reactivation.

Patients with decompensated cirrhosis have some problems which are difficult to treat because of the possibility of worsening decompensation that might interrupt DAA treatment and have an adverse impact on its effectiveness. Furthermore, the number of treatment regimens is limited because protease inhibitor-containing regimens are contraindicated in these groups of patients. The primary regimen for treating patients with decompensated cirrhosis is sofosbuvir and velpatasvir with weight-based ribavirin for 12 wk; in cases where ribavirin is contraindicated, it is recommended that the course of sofosbuvir and velpatasvir without ribavarin be extended to 24 wk[24]. Ribavarin should be started as low a dose as 600 mg daily, and dose escalation is dependent on the tolerance of the patients. For patients with decompensated (Child-Pugh B or C) cirrhosis with a model for end stage liver disease score > 18-20, liver transplantation should be the first choice of treatment if waiting lists do not exceed 6 mo. Referral to experienced centers with availability of liver transplantation could be the best option for this group of patients.

Men who have sex with men (MSM) have a high rate of HCV transmission and of reinfection after being cured with DAA treatment because they still continue to engage in high-risk behaviors that are prone to result in transmission of HCV. Recent data showed an increased incidence of HCV infection in HIV-infected MSM. HCV infection had an incidence of 6.35/1000 person-years among HIV-infected MSM, while the incidence of HCV infection in HIV negative MSM was low and similar to that of the general population (0.4/1000 person-years)[25]. The route of transmission is mostly from sexual contact, especially anal intercourse[26]. Although HIV pre exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) can reduce HIV transmission, it cannot eliminate the risk of HCV transmission in condomless anal sexual intercourse. A study from England revealed that two-thirds of HIV-negative patients who used PrEP acquired HCV via a sexual route[27]. Studies have shown that HIV/HCV coinfection MSM shed HCV in their semen[28], and they also had rectal shedding because rectal bleeding is associated with HCV transmission among HIV-infected MSM[29]. Annual screening for HCV infection among MSM is recommended for sexually active HIV-infected MSM and may be done more frequently depending on high-risk sexual behaviors. The treatment regimen of DAA is similar to that employed for heterosexual patients depending on genotype, treatment experience or comorbid diseases, but counseling about the risk of HCV reinfection is crucial, as is instruction about methods of reducing HCV reinfection risk after being cured of HCV infection[30].

Injection drug use (IDU) is an important risk factor for HIV and HCV transmission. Although patients with IDU run the risk of HCV reinfection, active or recent drug use is not a contraindication for HCV treatment. In low-resource countries with limited access to HCV therapy treatment for active IDU patients, there are still conflicts regarding this issue[31].

HCV infection is still a major issue among HIV-infected patients. Although in the DAA era, the efficacy of treatment is similar to that achieved in HCV monoinfection patients, drug interactions with ART and liver related morbidities are still a problem for patients receiving HIV/HCV treatment. Prompt initiation of HCV treatment and collaboration between hepatologists and HIV specialists could help to improve treatment outcomes.

| 1. | Rockstroh JK, Bhagani S, Benhamou Y, Bruno R, Mauss S, Peters L, Puoti M, Soriano V, Tural C; EACS Executive Committee. European AIDS Clinical Society (EACS) guidelines for the clinical management and treatment of chronic hepatitis B and C coinfection in HIV-infected adults. HIV Med. 2008;9:82-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 180] [Cited by in RCA: 166] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Soriano V, Puoti M, Sulkowski M, Cargnel A, Benhamou Y, Peters M, Mauss S, Bräu N, Hatzakis A, Pol S, Rockstroh J. Care of patients coinfected with HIV and hepatitis C virus: 2007 updated recommendations from the HCV-HIV International Panel. AIDS. 2007;21:1073-1089. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 258] [Cited by in RCA: 238] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Osibogun O, Ogunmoroti O, Michos ED, Spatz ES, Olubajo B, Nasir K, Madhivanan P, Maziak W. HIV/HCV coinfection and the risk of cardiovascular disease: A meta-analysis. J Viral Hepat. 2017;24:998-1004. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Osinusi A, Townsend K, Kohli A, Nelson A, Seamon C, Meissner EG, Bon D, Silk R, Gross C, Price A, Sajadi M, Sidharthan S, Sims Z, Herrmann E, Hogan J, Teferi G, Talwani R, Proschan M, Jenkins V, Kleiner DE, Wood BJ, Subramanian GM, Pang PS, McHutchison JG, Polis MA, Fauci AS, Masur H, Kottilil S. Virologic response following combined ledipasvir and sofosbuvir administration in patients with HCV genotype 1 and HIV co-infection. JAMA. 2015;313:1232-1239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 170] [Cited by in RCA: 173] [Article Influence: 15.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Berenguer J, Alvarez-Pellicer J, Martín PM, López-Aldeguer J, Von-Wichmann MA, Quereda C, Mallolas J, Sanz J, Tural C, Bellón JM, González-García J; GESIDA3603/5607 Study Group. Sustained virological response to interferon plus ribavirin reduces liver-related complications and mortality in patients coinfected with human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis C virus. Hepatology. 2009;50:407-413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 240] [Cited by in RCA: 239] [Article Influence: 14.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ghany MG, Morgan TR; AASLD-IDSA Hepatitis C Guidance Panel. Hepatitis C Guidance 2019 Update: American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases-Infectious Diseases Society of America Recommendations for Testing, Managing, and Treating Hepatitis C Virus Infection. Hepatology. 2020;71:686-721. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 348] [Cited by in RCA: 557] [Article Influence: 92.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Zuckerman AD, Douglas A, Whelchel K, Choi L, DeClercq J, Chastain CA. Pharmacologic management of HCV treatment in patients with HCV monoinfection vs. HIV/HCV coinfection: Does coinfection really matter? PLoS One. 2019;14:e0225434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Balagopal A, Kandathil AJ, Higgins YH, Wood J, Richer J, Quinn J, Eldred L, Li Z, Ray SC, Sulkowski MS, Thomas DL. Antiretroviral therapy, interferon sensitivity, and virologic setpoint in human immunodeficiency virus/hepatitis C virus coinfected patient. Hepatology. 2014;60:477-486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Naggie S, Cooper C, Saag M, Workowski K, Ruane P, Towner WJ, Marks K, Luetkemeyer A, Baden RP, Sax PE, Gane E, Santana-Bagur J, Stamm LM, Yang JC, German P, Dvory-Sobol H, Ni L, Pang PS, McHutchison JG, Stedman CA, Morales-Ramirez JO, Bräu N, Jayaweera D, Colson AE, Tebas P, Wong DK, Dieterich D, Sulkowski M; ION-4 Investigators. Ledipasvir and Sofosbuvir for HCV in Patients Coinfected with HIV-1. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:705-713. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 384] [Cited by in RCA: 383] [Article Influence: 34.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 10. | Abergel A, Metivier S, Samuel D, Jiang D, Kersey K, Pang PS, Svarovskaia E, Knox SJ, Loustaud-Ratti V, Asselah T. Ledipasvir plus sofosbuvir for 12 weeks in patients with hepatitis C genotype 4 infection. Hepatology. 2016;64:1049-1056. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 90] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Abergel A, Asselah T, Metivier S, Kersey K, Jiang D, Mo H, Pang PS, Samuel D, Loustaud-Ratti V. Ledipasvir-sofosbuvir in patients with hepatitis C virus genotype 5 infection: an open-label, multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2016;16:459-464. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Nguyen E, Trinh S, Trinh H, Nguyen H, Nguyen K, Do A, Levitt B, Do S, Nguyen M, Purohit T, Shieh E, Nguyen MH. Sustained virologic response rates in patients with chronic hepatitis C genotype 6 treated with ledipasvir+sofosbuvir or sofosbuvir+velpatasvir. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2019;49:99-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Naggie S, Cooper C, Saag M. Ledipasvir/sofosbuvir for 12 wk in patients coinfected with HCV and HIV-1. Presented at the 22st Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Seattle, WA, February 23-26, 2015. Abstract #152LB. |

| 14. | Garrison KL, German P, Mogalian E, Mathias A. The Drug-Drug Interaction Potential of Antiviral Agents for the Treatment of Chronic Hepatitis C Infection. Drug Metab Dispos. 2018;46:1212-1225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Rockstroh JK, Nelson M, Katlama C, Lalezari J, Mallolas J, Bloch M, Matthews GV, Saag MS, Zamor PJ, Orkin C, Gress J, Klopfer S, Shaughnessy M, Wahl J, Nguyen BYT, Barr E, Platt HL, Robertson MN, Sulkowski M. Efficacy and safety of grazoprevir (MK-5172) and elbasvir (MK- 8742) in patients with hepatitis C virus and HIV co-infection (C-EDGE CO-INFECTION): a non-randomised, open-label trial. Lancet HIV. 2015;2:e319-e327. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 245] [Cited by in RCA: 250] [Article Influence: 22.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Feng HP, Caro L, Dunnington KM, Guo Z, Cardillo-Marricco N, Wolford D. A clinically meaningful drug-drug interaction observed between Zepatier (Grazoprevir/Elbasvir) and Stribild HIV fixed dose combination in healthy subjects [Abstract O-22]. In: International Workshop on Clinical Pharmacology of HIV & Hepatitis Therapy. June 8-10, 2016. |

| 17. | Rockstroh JK, Lacombe K, Viani RM, Orkin C, Wyles D, Luetkemeyer AF, Soto-Malave R, Flisiak R, Bhagani S, Sherman KE, Shimonova T, Ruane P, Sasadeusz J, Slim J, Zhang Z, Samanta S, Ng TI, Gulati A, Kosloski MP, Shulman NS, Trinh R, Sulkowski M. Efficacy and Safety of Glecaprevir/Pibrentasvir in Patients Coinfected With Hepatitis C Virus and Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1: The EXPEDITION-2 Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;67:1010-1017. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 15.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kosloski MP, Oberoi R, Wang S, Viani RM, Asatryan A, Hu B, Ding B, Qi X, Kim EJ, Mensa F, Kort J, Liu W. Drug-Drug Interactions of Glecaprevir and Pibrentasvir Coadministered With Human Immunodeficiency Virus Antiretrovirals. J Infect Dis. 2020;221:223-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Wyles D, Bräu N, Kottilil S, Daar ES, Ruane P, Workowski K, Luetkemeyer A, Adeyemi O, Kim AY, Doehle B, Huang KC, Mogalian E, Osinusi A, McNally J, Brainard DM, McHutchison JG, Naggie S, Sulkowski M; ASTRAL-5 Investigators. Sofosbuvir and Velpatasvir for the Treatment of Hepatitis C Virus in Patients Coinfected With Human Immunodeficiency Virus Type 1: An Open-Label, Phase 3 Study. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;65:6-12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 124] [Cited by in RCA: 132] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Mogalian E, Stamm LM, Osinusi A, Brainard DM, Shen G, Ling KHJ, Mathias A. Drug-Drug Interaction Studies Between Hepatitis C Virus Antivirals Sofosbuvir/Velpatasvir and Boosted and Unboosted Human Immunodeficiency Virus Antiretroviral Regimens in Healthy Volunteers. Clin Infect Dis. 2018;67:934-940. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Wilson E, Covert E, Hoffmann J, Comstock E, Emmanuel B, Tang L, Husson J, Chua J, Price A, Mathur P, Rosenthal E, Kattakuzhy S, Masur H, Kottilil S. A pilot study of safety and efficacy of HCV retreatment with sofosbuvir/velpatasvir/voxilaprevir in patients with or without HIV (RESOLVE STUDY). J Hepatol. 2019;71:498-504. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Chu CJ, Lee SD. Hepatitis B virus/hepatitis C virus coinfection: epidemiology, clinical features, viral interactions and treatment. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:512-520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Collins JM, Raphael KL, Terry C, Cartwright EJ, Pillai A, Anania FA, Farley MM. Hepatitis B Virus Reactivation During Successful Treatment of Hepatitis C Virus With Sofosbuvir and Simeprevir. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61:1304-1306. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 134] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 11.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Curry MP, O'Leary JG, Bzowej N, Muir AJ, Korenblat KM, Fenkel JM, Reddy KR, Lawitz E, Flamm SL, Schiano T, Teperman L, Fontana R, Schiff E, Fried M, Doehle B, An D, McNally J, Osinusi A, Brainard DM, McHutchison JG, Brown RS Jr, Charlton M; ASTRAL-4 Investigators. Sofosbuvir and Velpatasvir for HCV in Patients with Decompensated Cirrhosis. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2618-2628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 599] [Cited by in RCA: 628] [Article Influence: 57.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Jin F, Matthews GV, Grulich AE. Sexual transmission of hepatitis C virus among gay and bisexual men: a systematic review. Sex Health. 2017;14:28-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Bradshaw D, Vasylyeva TI, Davis C, Pybus OG, Thézé J, Thomson EC, Martinello M, Matthews GV, Burholt R, Gilleece Y, Cooke GS, Page EE, Waters L, Nelson M. Transmission of hepatitis C virus in HIV-positive and PrEP-using MSM in England. J Viral Hepat. 2020;27:721-730. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Turner SS, Gianella S, Yip MJ, van Seggelen WO, Gillies RD, Foster AL, Barbati ZR, Smith DM, Fierer DS. Shedding of Hepatitis C Virus in Semen of Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Infected Men. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2016;3:ofw057. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Foster AL, Gaisa MM, Hijdra RM, Turner SS, Morey TJ, Jacobson KB, Fierer DS. Shedding of Hepatitis C Virus Into the Rectum of HIV-infected Men Who Have Sex With Men. Clin Infect Dis. 2017;64:284-288. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2015 sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, special populations [Internet]. 2015. [cited 20 January 2021] Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/specialpops.htm. |

| 30. | Martin TC, Singh GJ, McClure M, Nelson M. HCV reinfection among HIV-positive men who have sex with men: a pragmatic approach. Hepatology. 2015;61:1437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Aspinall EJ, Corson S, Doyle JS, Grebely J, Hutchinson SJ, Dore GJ, Goldberg DJ, Hellard ME. Treatment of hepatitis C virus infection among people who are actively injecting drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57 Suppl 2:S80-S89. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 246] [Cited by in RCA: 262] [Article Influence: 21.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Thailand

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C, C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Hanafy AS, Yao DF, Zheng S S-Editor: Gong ZM L-Editor: Filipodia P-Editor: Liu JH