Published online Oct 26, 2020. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v8.i20.4763

Peer-review started: June 28, 2020

First decision: August 8, 2020

Revised: August 20, 2020

Accepted: August 29, 2020

Article in press: August 29, 2020

Published online: October 26, 2020

Processing time: 120 Days and 0.4 Hours

Undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver (UESL) is a rare liver malignancy originating from primary mesenchymal tissue. The clinical manifestations, laboratory tests, and imaging examinations of the disease lack specificity and the preoperative misdiagnosis rate is high. The overall prognosis is poor and survival rate is low.

To investigate the diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of UESL.

We performed a retrospective, single-center cohort study in Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University, which is a central hospital in northeast China. From 2005 to 2017, we recruited 14 patients with pathologically confirmed UESL. We analyzed the clinical manifestations, laboratory tests, imaging examinations, pathological examinations, therapy, and prognosis of these patients.

There were nine males and five females aged 2-60 years old included in the study. The major initial symptoms were abdominal pain (71.43%) and fever (57.14%). Preoperative laboratory tests revealed that seven patients had increased leukocyte levels, four showed a decrease in hemoglobin levels, seven patients had increased glutamyl transpeptidase levels, nine had increased lactate dehydrogenase levels, and three showed an increase in carbohydrate antigen 199. There was no difference in the rate of misdiagnosis in preoperative imaging examinations of UESL between adults and children (6/6 vs 5/8, P = 0.091). The survival rate after complete resection was 6/10, while that after incomplete resection was 0/4 (P = 0.040), suggesting that complete resection is important to improve survival rate. In total, five out of the eight children achieved survival. During the follow-up, the maximum survival time was shown to be 11 years and minimum survival time was 6 mo. Six adult patients relapsed late after surgery and all of them died.

Preoperative imaging examination for UESL has a high misdiagnosis rate. Multidisciplinary collaboration can improve the diagnostic accuracy of UESL. Complete surgical resection is the first choice for treatment of UESL.

Core Tip: Undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver is rarely seen in clinical practice; it is difficult to diagnose and easily misdiagnosed before surgery. Comprehensive treatment based on complete surgical resection is the key for long-term survival. The methods for diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis evaluation of the disease should be further investigated.

- Citation: Zhang C, Jia CJ, Xu C, Sheng QJ, Dou XG, Ding Y. Undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver: Clinical characteristics and outcomes. World J Clin Cases 2020; 8(20): 4763-4772

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v8/i20/4763.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v8.i20.4763

Undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver (UESL) is a rare liver malignancy originating from primary mesenchymal tissue[1]. The disease is more common in children but it can also occur in adults. The incidence of the disease ranks fourth in terms of liver malignancies in children, accounting for 9%-13% of cases[2-4]. UESL has no sex predilection in children and a slight female predominance in adults[5]. The clinical manifestations are non-specific, often include abdominal pain, fever, and hepatomegaly. The imaging examination usually shows a large, solitary nodule in the right liver lobe. Some cases are accompanied by extrahepatic spread[5-6]. The clinical manifestations, laboratory tests, and imaging examinations of the disease lack specificity and the preoperative misdiagnosis rate is high. The definitive diagnosis of the disease depends on histopathology and immunohistochemistry. The overall prognosis is poor and survival rate is low[7].

In this study, we retrospectively analyzed the clinical, imaging, and histopathological findings of 14 patients with UESL treated at the Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University between 2005 and 2017. This study is a single-center retrospective study with a large time span and wide age distribution among the enrolled patients. The clinical manifestations, laboratory and imaging examinations, and preoperative and postoperative diagnosis were comprehensively evaluated. And the patients were followed for a long time to investigate the impact of surgery and chemotherapy on prognosis. The results obtained will help to improve the clinician’s understanding of the UESL.

The following clinical data of 14 patients with UESL were collected and analyzed: General information including sex, age, and disease and treatment history; primary symptoms and positive signs; laboratory test results including routine blood tests, liver function, tumor biomarkers, and hepatitis virus markers; imaging examination results including ultrasonography and computed tomography (CT) examinations; postoperative histopathological and immunohistochemical examinations; preoperative and postoperative diagnosis; and surgery and postoperative chemotherapy. Ultrasonography or CT scan was performed every 3-6 mo during every year of follow-up to monitor tumor recurrence.

Patients were not required to give informed consent to the study because the analyses used anonymous clinical data that were obtained after each patient had agreed to treatment by written consent. This study was approved by The Ethical Committee of Shengjing Hospital.

Statistical software SPSS 21.0 (SPSS, Chicago, IL, United States) was used for statistical processing and analyses. The statistical review of the study was performed by a biomedical statistician (Li-Qiang Zheng, PhD, Department of Clinical Epidemiology, Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University). Categorical variables are presented as number and percentage and their inter-group comparison was performed by χ2 test. Significant difference was deemed at P < 0.05.

The sample consisted of 14 patients with UESL aged 2–60 years old, including nine males and five females. Eight patients were under 15 years of age, with average and median ages of 8 and 10 years, respectively. Six patients were older than 45 years old, and their average and median ages were 53 and 49 years. The duration of the disease among the patients ranged from 4 d to 1 mo. The major initial symptoms were abdominal pain (71.43%) and fever (57.14%). Most patients had a body temperature < 38.5°C; only one patient had a maximum temperature of 40.5°C. Fever in the patients was generally not accompanied by chills. Nausea was described in 28.57% (4/14) of the patients. An abdominal mass was only found in children and accounted for 28.57% (4/14) of cases, and three of these children underwent emergency surgery due to tumor rupture. None of the 14 patients had a history of chronic hepatitis or cirrhosis, and only one female adult patient had a history of systemic lupus erythematosus and oral hormone therapy.

Preoperative laboratory tests showed that seven patients exhibited an increase in leukocyte levels (11.2-25.5 × 109 /L), four showed a decrease in hemoglobin levels (54-96 g/L), five had mild hypoalbuminemia (32-34.8 g/L), seven showed an increase in glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT; 87-419 U/L), nine showed an increase in lactate dehydrogenase (LDH; 253-4587 U/L), and three displayed an increase in carbohydrate antigen 199 (CA199; 54-131.5 U/L). All patients had normal alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and total bilirubin (TBil) levels, and hepatitis virus markers were all negative. The levels of α-fetoprotein (AFP) of the patients were also in normal ranges.

Ultrasound: Nine patients underwent an abdominal ultrasound examination. Cystic-solid mixed masses were found in six children. The masses were generally solid-dominant and separated by liquid components. The boundaries were unclear and internal echo was not uniform. In three adult patients, the masses were shown as having a heterogeneous moderately echoic and hypoechoic appearance with unclear edges on sonography.

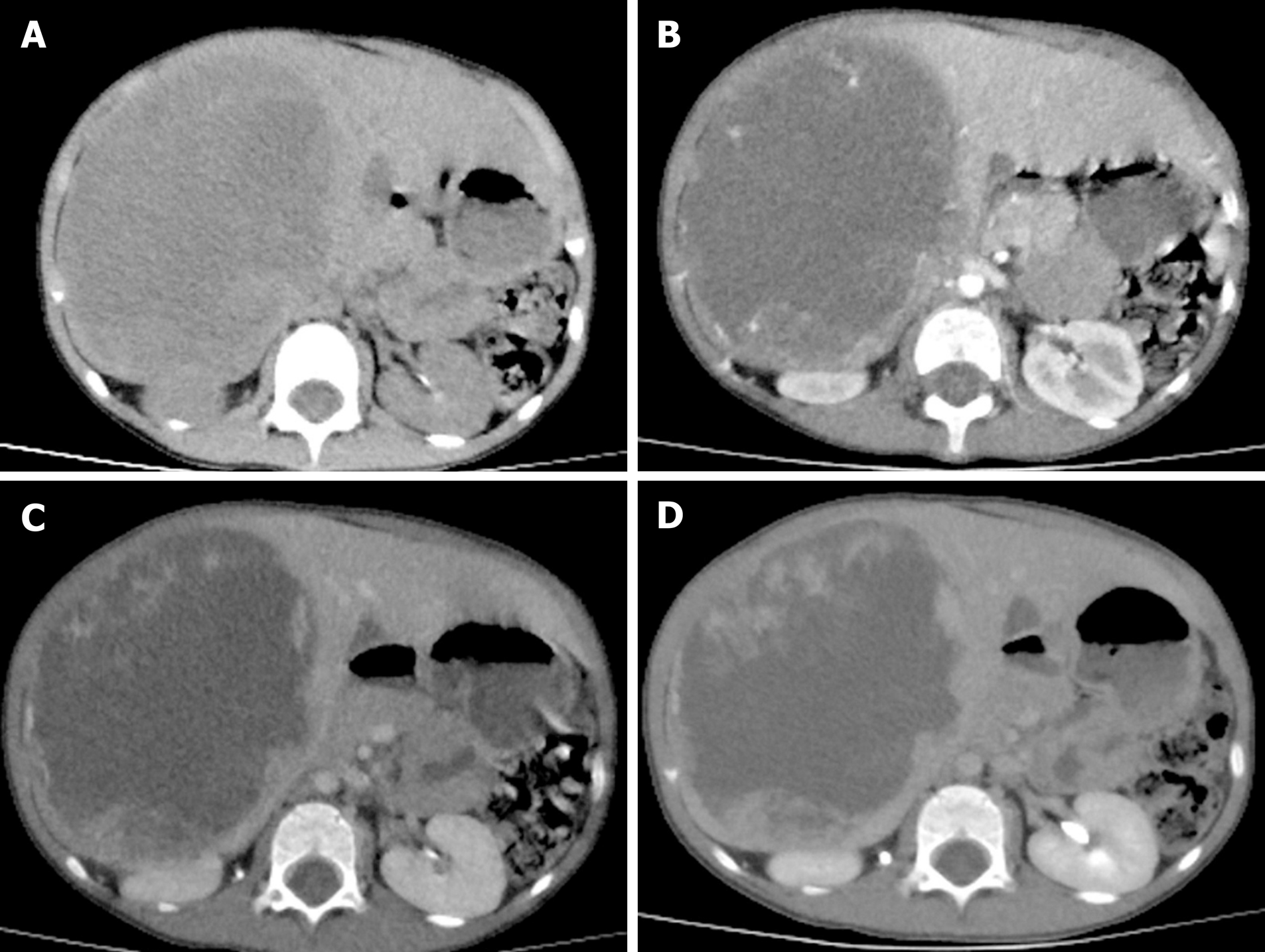

CT examination: One child received an ultrasound examination, although this was only because of emergency surgery. All of the remaining 13 patients underwent CT examinations. In the plain scan, cystic-solid mixed hypodense masses were found in seven children, and there were liquid areas in the masses. The solid components showed mild or significant enhancement in the arterial phase in contrast scans. The enhancement was strengthened in the venous phase. Plain scans in six adult patients showed irregular, slightly-hypodense masses. The enhancement of the masses was significantly lower than that of surrounding parenchyma in the arterial phase and increased gradually; however, until the delayed phase, the enhancement of the mass was still lower than that of the surrounding parenchyma (Figure 1 and 2).

The rates of misdiagnosis in preoperative imaging examination of UESL in children and adults were 62.5% (5/8) and 100% (6/6), respectively. There was no difference in the rate of misdiagnosis between adults and children (P = 0.091). Among the eight cases of UESL in children, one patient was diagnosed as having liver cystadenocarcinoma, two were diagnosed as having hepatoblastoma complicated with rupture and hemorrhage, two were diagnosed as having a liver abscess, and in the remaining three cases there was a high suspicion of UESL. Among the six adult patients with UESL, three, two, and one patient were misdiagnosed as having primary hepatocellular carcinoma, a liver abscess, and a hepatic cyst, respectively.

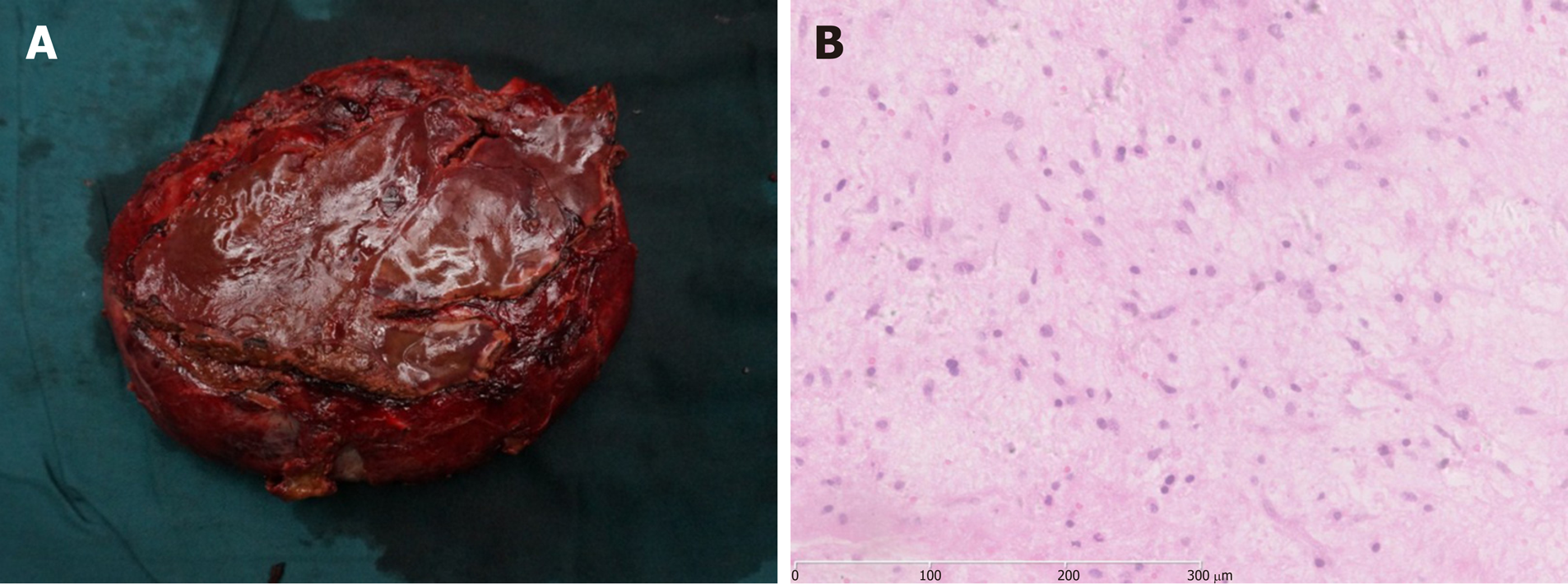

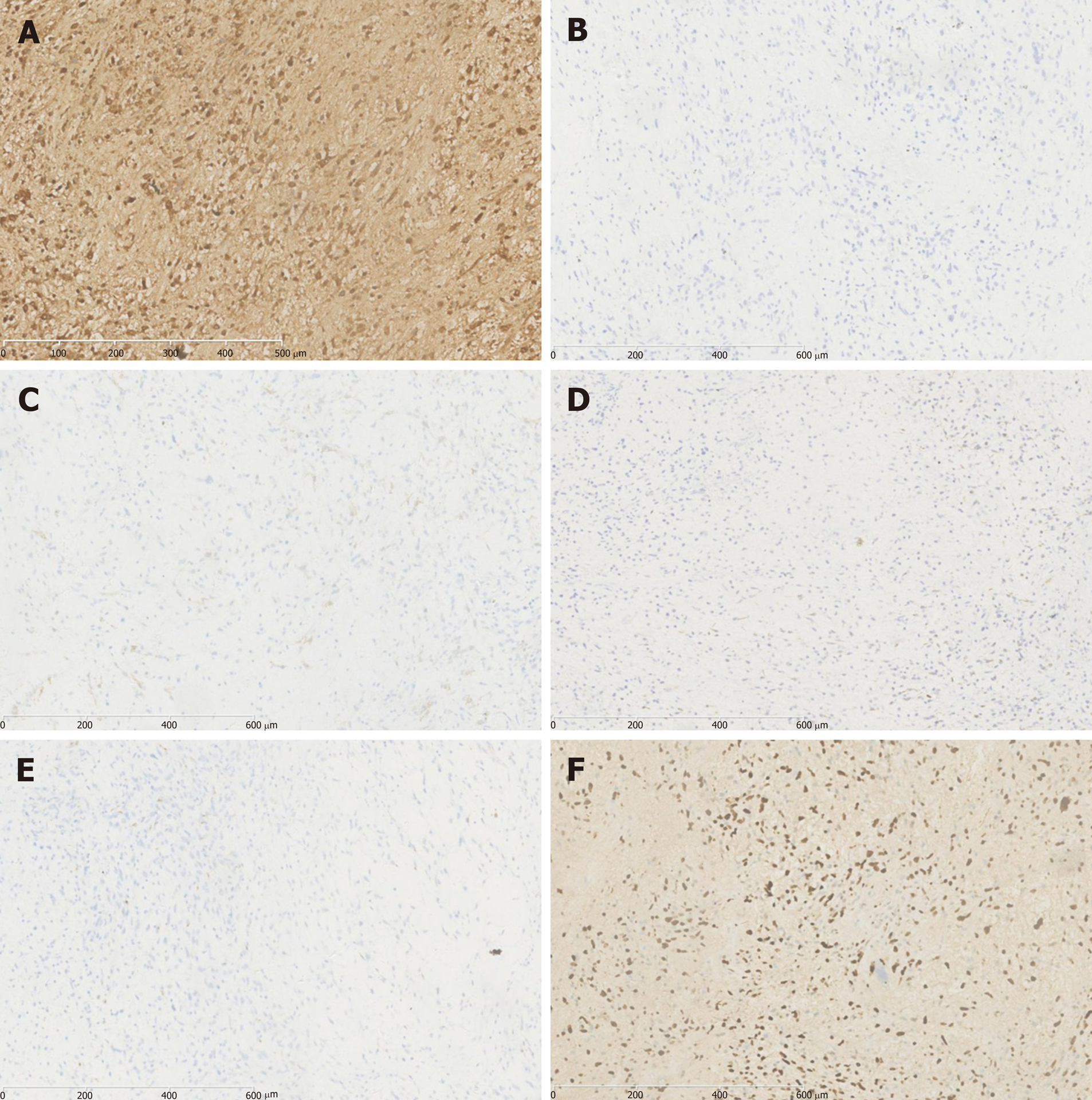

All of the 14 cases were confirmed as UESL by histopathological and immuno-histochemical examinations of the resected specimens. The tumors were cystic-solid mixed or solid masses with a long diameter of 6–22 cm in gross anatomical analyses. The cystic part contained jelly-like or blood-like components; the texture of the solid part was soft, and sections showed a dark red or pink-white color; bleeding and necrosis could be observed. Microscopy showed that tumor tissue was composed of undifferentiated mesenchymal cells and a mucus matrix. Tumor cells displayed significant atypia and were of spindle or polygonal shape. Tumor giant cells could be found. Eosinophilic bodies were found between tumor cells, accompanied by bleeding and necrosis. Immunohistochemical staining revealed vimentin (+), α1-antitrypsin (AAT) (+), AFP (–), epithelial membrane antigen (EMA) (–), smooth muscle actin (SMA) (–), cytokeratin (CK) (–), and hepatocyte (–) (Figure 3).

Surgery: There were ten cases in which the tumor lesions were in the right lobe, one case in which the tumor lesion was in the caudate lobe, and in three patients the tumor lesions were in the right lobe and left anterior lobe. According to the location and distribution of the tumor lesions, three-lobe resection of the right liver was performed in six cases, combined hepatic segmentectomy was performed in seven, and caudate lobe resection was performed in one. Complete tumor resection was performed in ten cases and incomplete tumor resection was performed in four (all were adult patients). Three patients who had anemia and were suspected of having tumor rupture and hemorrhage before operation had this confirmed by emergency surgery. Tumor invasion of the diaphragm occurred in three patients. Two children with intrahepatic recurrence underwent re-surgery.

Chemotherapy: None of patients received chemotherapy in addition to percutaneous transhepatic arterial chemoembolization before surgery. Six patients completed eight cycles of postoperative chemotherapy (vincristine + cyclophosphamide + epirubicin or vincristine + actinomycin D + cyclophosphamide). Three patients discontinued chemotherapy due to toxicity after one or two cycles of the treatment, and five patients declined chemotherapy.

Follow-up lasted until September 2017. The longest follow-up period was 11 years and the shortest was 6 mo; two patients (children) were lost to follow-up. Among the ten patients who had undergone complete resection (two patients were lost to follow-up), six survived. In contrast, all four patients who had undergone incomplete resection (all were adult patients) died. Complete resection is important to improve survival rate (P = 0.040; it was believed that the two patients lost to follow-up were dead). Five out of the eight children achieved survival. The maximum survival time to the end of follow-up was 11 years and minimum survival time was 6 mo. One child achieved tumor-free survival for 5 years. Three patients relapsed and there was no recurrence in the two cases after re-surgery; the postoperative tumor-free survival time of two patients was 24 mo and 30 mo, respectively. One case died because of rejecting re-surgery. Six adult cases had a late relapse 6–30 mo after operation and all of them died. The causes of death were intrahepatic recurrence and distant metastasis.

UESL was first reported and named by Stocher and Ishak in 1978[1]. It is a malignant liver tumor composed of undifferentiated malignant mesenchymal cells. UESL is rarely seen in clinical practice and accounts for only 0.1% of surgically-resected primary liver lesions[7]. The peak onset of the disease occurs between 6 and 15 years of age[8]. The disease is a common liver malignancy in children, only behind hepatoblastoma, hepatic epithelioid hemangioendothelioma, and hepatocellular carcinoma in terms of frequency[2]. UESL is rarely reported in adults[9]. The reported oldest patient was 86 years old[10]. UESL accounts for fewer than 1% of all primary liver neoplasms in adults[11]. In this study, we retrospectively analyzed 14 cases of UESL in our hospital over the last 12 years. There were eight patients under 15 years of age. Of note, adult patients were not uncommon in this cohort; six (42.86%) out of 14 patients were older than 45 years of age.

The etiology and pathogenesis of UESL are not fully understood. Mesenchymal hamartoma and UESL share the same cytogenetic abnormality, and they are often considered to be the entities of the same spectrum of diseases[12,13]. It has been reported that UESL cases can be accompanied by the amplification or deletion in chromosomes 1q, 5p, 8p, and 12q, and the translocation of 19q13.4[8]. Aberrations in chromosomes 6, 11, 12, 14, and X, and mutations in p53 have also been reported[14,15]. UESL is generally not complicated with initial liver diseases such as hepatitis B and hepatitis C; however, adult UESL cases complicated with multiple sclerosis or with a chemotherapy history have been reported[16,17]. In our patients, only one female adult patient had a history of systemic lupus erythematosus and long-term use of oral hormone therapy; it is not clear whether the situation was associated with UESL pathogenesis. Hepatitis or other special disease history was not found in other patients. The detection of molecular genetics could be beneficial for the differential diagnosis of UESL.

UESL usually lacks specific clinical manifestations. In children, the disease can present with abdominal pain and fever, which may be caused by intratumoral hemorrhage, necrosis, and infection[18]. A palpable upper abdominal mass, accompanied by varying degrees of tenderness, can be detected on physical examination. The advanced tumor grows at a faster rate and is often complicated with intratumoral hemorrhage or spontaneous rupture. A few patients are admitted as a result of acute abdominal syndrome due to tumor rupture and bleeding[19]. In our 14 UESL patients, ten had abdominal pain and eight had fever. A palpable upper abdominal mass was only found in four patients (children), of whom three underwent emergency surgery because of tumor rupture and bleeding. Adult patients only had mild upper abdominal pain and discomfort; the tumor was relatively small and no palpable upper abdominal mass was found in adult patients.

There are no specific laboratory tests for UESL. Although UESL patients generally do not have initial liver diseases such as hepatitis and cirrhosis, because the tumor has a large volume and squeezes the surrounding normal liver tissue, liver function may be abnormal. For example, the elevation of ALT and TBil can be seen. The increase in leukocytes can be detected in cases complicated with intratumoral hemorrhage, necrosis, and infection[18]. The serum tumor biomarkers in UESL patients are usually negative, although in adults increases in AFP, CA125, and CA199 have been reported[20-22]. Among the 14 patients in our study, seven were misdiagnosed as having a liver abscess because of the leukocyte increase in preoperative blood tests. Anti-infective therapy was ineffective in these patients. A decrease in hemoglobin was detected in four patients, three of which subsequently underwent emergency surgery due to tumor rupture and bleeding. ALT and TBil levels were normal in all patients, and increases of GGT and CA199 were found in seven and three patients, respectively. Nine patients displayed a significant increase in LDH. A previous study reported that 71.43% of children with UESL had increased LDH levels[23]; however, the reason is still unclear.

On ultrasound examination, UESL often shows solid-dominant mixed echogenic masses; in CT images, tumors are displayed as a cystic-solid mixed (cystic-dominant) space-occupying lesions with characterized delayed enhancement. The lesions are dominantly cystic because part of the gel-like component in the tumor is shown as having a region with water-like density on CT[24]. Such an inconsistency in ultrasound and CT examination is a diagnostic feature of the disease and the misdiagnosis rate of imaging examination is 23.5%[25]. Due to insufficient understanding of the disease, the misdiagnosis rates of preoperative imaging examination in our children and adult patients were 62.5% and 100%, respectively. The clinical manifestations and examination of UESL lack specificity, and preoperative diagnosis of UESL is difficult, particularly for adult patients. Definitive diagnosis is often made through multidisciplinary collaboration. Surgical histopathology and immunohistochemistry tests are the main measures to confirm diagnosis of UESL. Only three pediatric patients in this study were diagnosed with UESL preoperatively. Four cases were misdiagnosed as having a liver abscess due to fever, leukocyte increase, and liver lesions. They had a poor response to anti-infective treatment and were finally diagnosed by surgical histopathology after multidisciplinary collaboration. The UESL lesions are generally in the right lobe of the liver and measure about 10–30 cm in diameter. However, it was reported that postoperative recurrent lesions were located in the left lobe[22]. Among our patients, ten had lesions in the right lobe, which was consistent with previous reports. In gross anatomy examinations, the tumors had a dark red section with cystic degeneration, bleeding, and necrosis. Under the microscope, spindle-shaped undifferentiated mesenchymal cells could be found in a loose mucus matrix. The tumor cells were mononuclear or multinuclear, and nuclear deformity and mitotic figures could also be observed. Immunohistochemical staining demonstrated that vimentin and AAT were diffusely expressed in most UESL lesions. The most characteristic pathological evidence is the presence of eosinophilic bodies with varying sizes found in the cytoplasm of large tumor cells or in the extracellular matrix; periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) staining of these structures is positive[26]. Moreover, CK, SMA, myoglobin, S-100, and CD34 can be expressed locally in parts of the lesions[27]. In our patients, immunohistochemical staining showed all were positive in the expression of vimentin and AAT, one patient had focal expression of SMA, and CK, and other antigens were negative, suggesting that the tumor cells originated from primitive mesenchymal cells, with a few of the tumor cells differentiating toward smooth muscle cells. The pathological diagnosis of UESL is difficult in some cases but is of great importance. Three of our patients were definitively diagnosed by a group of experienced pathologists from multiple hospitals.

UESL is a highly malignant tumor; at diagnosis, most patients have already progressed to the advanced stages. The postoperative recurrence rate of the disease is high and survival rate is only 37%[28]. Multimodal therapies in patients with UESL have improved survival rates, ranging from 70% to 100%[29,30]. Therefore, it is accepted that the comprehensive treatment based on complete resection of the tumor is the key for long-term survival. For example, a combination with systemic chemotherapy can shrink the tumor, improve the radical resection rate, and prolong postoperative survival[31-33]. May et al[34] reported on five pediatric UESL patients treated by surgical resection combined with chemotherapy; the average postoperative tumor-free survival time reached 53 mo. Another study also suggested that the efficacy of surgery in combination with postoperative chemotherapy was better than that of surgery alone[35]. Transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE) may be applied as a preoperative therapy for children with unresectable UELS. The size of the tumors was reduced after TACE. The tumors were completely removed by surgical procedures after TACE[35]. For those who were chemotherapy-intolerant, did not undergo surgery, or relapsed after operation, some studies suggested that liver transplantation was an option. Overall survival in these five patients was 100%, with a follow-up period ranging from 21 mo to 68 mo. Disease-free survival ranged from 8 mo to 46 mo, and no patients had residual disease[30]. In our patients, tumors were completely resected in ten cases. Pediatric patients had a relatively good prognosis and longer tumor-free survival. The patients with intrahepatic recurrence who had undergone re-surgery also had a good prognosis. On the contrary, the adult patients all died due to incomplete resection of the tumors. Our study showed that postoperative chemotherapy could reduce recurrence and improve survival.

Our study has some limitations. First, this is a single-center study, and the disease is a rare disease. Although the time span is large, the relatively small number of cases would lead to biases in the observation of clinical manifestations and laboratory/imaging examinations. Second, retrospective research usually has intrinsic bias. In this study, patients came from the same center with complete clinical data and uniform diagnostic criteria, which can minimize such bias.

In conclusion, the clinical manifestations and tests of the UESL have low specificity, resulting in the difficulty in preoperative diagnosis and high possibility of misdiagnosis. Multidisciplinary collaboration is recommended for suspected cases. Comprehensive treatment based on complete resection of the tumor is the key for long-term survival. The standards and efficacy of comprehensive treatment need to be further investigated.

Undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver (UESL) is a rare liver malignancy originating from primary mesenchymal tissue. The clinical manifestations, laboratory tests, and imaging examinations of the UESL lack specificity and the preoperative misdiagnosis rate is high.

Analyzing the clinical characteristics of UESL, summarizing the diagnostic criteria, and discussing the best treatment scheme are of great significance for the diagnosis and treatment of this malignancy.

The aim of this study was to investigate the diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of UESL.

This study is a single-center retrospective study with a large time span and wide age distribution among the enrolled patients. From 2005 to 2017, we recruited 14 patients with pathologically confirmed UESL. We analyzed the clinical manifestations, laboratory tests, imaging examinations, pathological examinations, therapy, and prognosis of these patients.

There were nine males and five females aged 2–60 years old included in the study. The major initial symptoms were abdominal pain (71.43%) and fever (57.14%). Preoperative misdiagnosis rate was high, and there was no difference between adults and children. Complete resection was important to improve survival rate.

Preoperative imaging examination for UESL has a high misdiagnosis rate. Multidisciplinary collaboration can improve the diagnostic accuracy of UESL. Complete surgical resection is the first choice for treatment of UESL.

The standards and efficacy of comprehensive treatment need to be further investigated.

We thank our colleagues for the treatment of these cases, and these patients and family members who agreed to publication of these cases.

| 1. | Stocker JT, Ishak KG. Undifferentiated (embryonal) sarcoma of the liver: report of 31 cases. Cancer. 1978;42:336-348. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Muthuvel E, Chander V, Srinivasan C. A Clinicopathological Study of Paediatric Liver Tumours in a Tertiary Care Hospital. J Clin Diagn Res. 2017;11:EC50-EC53. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Weinberg AG, Finegold MJ. Primary hepatic tumors of childhood. Hum Pathol. 1983;14:512-537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 375] [Cited by in RCA: 301] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Shattaf A, Jamil A, Khanani MF, El-Hayek M, Baroudi M, Trad O, Ishaqi MK. Undifferentiated sarcoma of the liver: a rare pediatric tumor. Ann Saudi Med. 2012;32:203-205. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Wu Z, Wei Y, Cai Z, Zhou Y. Long-term survival outcomes of undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver: a pooled analysis of 308 patients. ANZ J Surg. 2020;90:1615-1620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Martins-Filho SN, Putra J. Hepatic mesenchymal hamartoma and undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver: a pathologic review. Hepat Oncol. 2020;7:HEP19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Cong WM, Dong H, Tan L, Sun XX, Wu MC. Surgicopathological classification of hepatic space-occupying lesions: a single-center experience with literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:2372-2378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Webber EM, Morrison KB, Pritchard SL, Sorensen PH. Undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver: results of clinical management in one center. J Pediatr Surg. 1999;34:1641-1644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lee KH, Maratovich MN, Lee KB. Undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver in an adult patient. Clin Mol Hepatol. 2016;22:292-295. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lenze F, Birkfellner T, Lenz P, Hussein K, Länger F, Kreipe H, Domschke W. Undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver in adults. Cancer. 2008;112:2274-2282. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 62] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Noguchi K, Yokoo H, Nakanishi K, Kakisaka T, Tsuruga Y, Kamachi H, Matsushita M, Kamiyama T. A long-term survival case of adult undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of liver. World J Surg Oncol. 2012;10:65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lauwers GY, Grant LD, Donnelly WH, Meloni AM, Foss RM, Sanberg AA, Langham MR Jr. Hepatic undifferentiated (embryonal) sarcoma arising in a mesenchymal hamartoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 1997;21:1248-1254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 116] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Shehata BM, Gupta NA, Katzenstein HM, Steelman CK, Wulkan ML, Gow KW, Bridge JA, Kenney BD, Thompson K, de Chadarévian JP, Abramowsky CR. Undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver is associated with mesenchymal hamartoma and multiple chromosomal abnormalities: a review of eleven cases. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 2011;14:111-116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Gao J, Fei L, Li S, Cui K, Zhang J, Yu F, Zhang B. Undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver in a child: A case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2013;5:739-742. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sangkhathat S, Kusafuka T, Nara K, Yoneda A, Fukuzawa M. Non-random p53 mutations in pediatric undifferentiated (embryonal) sarcoma of the liver. Hepatol Res. 2006;35:229-234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Tanaka S, Takasawa A, Fukasawa Y, Hasegawa T, Sawada N. An undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver containing adipophilin-positive vesicles in an adult with massive sinusoidal invasion. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2012;5:824-829. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Kullar P, Stonard C, Jamieson N, Huguet E, Praseedom R, Jah A. Primary hepatic embryonal sarcoma masquerading as metastatic ovarian cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2009;7:55. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Wei ZG, Tang LF, Chen ZM, Tang HF, Li MJ. Childhood undifferentiated embryonal liver sarcoma: clinical features and immunohistochemistry analysis. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43:1912-1919. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Sakellaridis T, Panagiotou I, Georgantas T, Micros G, Rontogianni D, Antiochos C. Undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver mimicking acute appendicitis. Case report and review of the literature. World J Surg Oncol. 2006;4:9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Dai CL, Xu F, Shu H, Xu YQ, Huang Y. Undifferentiated (embryonal) sarcoma of liver in adult: a case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:926-929. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Almogy G, Lieberman S, Gips M, Pappo O, Edden Y, Jurim O, Simon Slasky B, Uzieli B, Eid A. Clinical outcomes of surgical resections for primary liver sarcoma in adults: results from a single centre. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2004;30:421-427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Hanafiah M, Yahya A, Zuhdi Z, Yaacob Y. A case of an undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver mimicking a liver abscess. Sultan Qaboos Univ Med J. 2014;14:e578-e581. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Qin H, Zhu XD, Wang HM, Zhang JZ, Liu T. Diagnosis and treatment of undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver in children: 14 cases. Chin J Cancer Prev Treat. 2009;16:1108-1110. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 24. | Qiu LL, Yu RS, Chen Y, Zhang Q. Sarcomas of abdominal organs: computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging findings. Semin Ultrasound CT MR. 2011;32:405-421. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Charfi S, Ayadi L, Toumi N, Frikha F, Daoud E, Makni S, Frikha M, Beyrouti MI, Sellami-Boudawara T. Cystic undifferentiated sarcoma of liver in children: a pitfall diagnosis in endemic hydatidosis areas. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43:E1-E4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Mori A, Fukase K, Masuda K, Sakata N, Mizuma M, Ohtsuka H, Morikawa T, Nakagawa K, Hayashi H, Motoi F, Naitoh T, Murakami K, Unno M. A case of adult undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver successfully treated with right trisectionectomy: a case report. Surg Case Rep. 2017;3:19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Li XW, Gong SJ, Song WH, Zhu JJ, Pan CH, Wu MC, Xu AM. Undifferentiated liver embryonal sarcoma in adults: a report of four cases and literature review. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:4725-4732. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Leuschner I, Schmidt D, Harms D. Undifferentiated sarcoma of the liver in childhood: morphology, flow cytometry, and literature review. Hum Pathol. 1990;21:68-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Bisogno G, Pilz T, Perilongo G, Ferrari A, Harms D, Ninfo V, Treuner J, Carli M. Undifferentiated sarcoma of the liver in childhood: a curable disease. Cancer. 2002;94:252-257. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 132] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Plant AS, Busuttil RW, Rana A, Nelson SD, Auerbach M, Federman NC. A single-institution retrospective cases series of childhood undifferentiated embryonal liver sarcoma (UELS): success of combined therapy and the use of orthotopic liver transplant. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2013;35:451-455. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Shi Y, Rojas Y, Zhang W, Beierle EA, Doski JJ, Goldfarb M, Goldin AB, Gow KW, Langer M, Meyers RL, Nuchtern JG, Vasudevan SA. Characteristics and outcomes in children with undifferentiated embryonal sarcoma of the liver: A report from the National Cancer Database. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017;64:e26272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Techavichit P, Masand PM, Himes RW, Abbas R, Goss JA, Vasudevan SA, Finegold MJ, Heczey A. Undifferentiated Embryonal Sarcoma of the Liver (UESL): A Single-Center Experience and Review of the Literature. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2016;38:261-268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Murawski M, Scheer M, Leuschner I, Stefanowicz J, Bonar J, Dembowska-Bagińska B, Kaliciński P, Koscielniak E, Czauderna P, Fuchs J. Undifferentiated sarcoma of the liver: Multicenter international experience of the Cooperative Soft-Tissue Sarcoma Group and Polish Paediatric Solid Tumor Group. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2020;67:e28598. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | May LT, Wang M, Albano E, Garrington T, Dishop M, Macy ME. Undifferentiated sarcoma of the liver: a single institution experience using a uniform treatment approach. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol. 2012;34:e114-e116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Zhao X, Xiong Q, Wang J, Li MJ, Qin Q, Huang S, Gu W, Shu Q, Tou J. Preoperative Interventional Therapy for Childhood Undifferentiated Embryonal Liver Sarcoma: Two Retrospective Cases from a Single Center. European J Pediatr Surg Rep. 2015;3:90-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): A

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Calle R, Kachru N, Yoshio S S-Editor: Wang DM L-Editor: Wang TQ P-Editor: Zhang YL