Published online Dec 26, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i24.4334

Peer-review started: May 14, 2019

First decision: September 9, 2019

Revised: October 22, 2019

Accepted: November 14, 2019

Article in press: November 14, 2019

Published online: December 26, 2019

Processing time: 229 Days and 6.2 Hours

Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD) is a rare severe complication after renal transplantation, with an incidence of approximately 0.3%-2.0% in patients undergoing renal transplantation. The clinical manifestations of PTLD are often nonspecific, leading to tremendous challenges in the clinical diagnosis and treatment of PTLD.

We report two Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)-positive PTLD cases whose main clinical manifestations were digestive tract symptoms. Both of them admitted to our hospital because of extranodal infiltration symptoms and we did not suspect of PTLD until the pathology confirmation. Luckily, they responded well to the treatment of rituximab. We also discuss the virological monitoring, clinical characteristics, diagnosis, and treatment of PTLD.

PTLD is a deceptive disease and difficult to diagnose. Once patients are confirmed with PTLD, immune suppressant dosage should be immediately reduced and rituximab should be used as first-line therapy.

Core tip: Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD) is a rare severe complication after renal transplantation, with an incidence of approximately 0.3%-2.0% in patients undergoing renal transplantation. We report two Epstein-Barr virus-positive PTLD cases whose main clinical manifestations were digestive tract symptoms. As both of them admitted to our hospital because of extranodal infiltration symptoms, we did not suspect of PTLD until the pathology confirmation. We also discuss the virological monitoring, clinical characteristics, diagnosis, and treatment of PTLD.

- Citation: Sun ZJ, Hu XP, Fan BH, Wang W. Epstein-Barr virus-positive post-transplant lymphoproliferative disordepresenting as hematochezia and enterobrosis in renal transplant recipients in China: A report of two cases. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(24): 4334-4341

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i24/4334.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i24.4334

In adult renal transplant recipients in Europe and America, the incidence of post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder (PTLD) is only second to that of skin cancer. In China, tumors of the urinary system are still the main malignancies in renal transplant recipients. The postoperative 1- and 5-year incidences of PTLD are only 0.2% and 0.6%, respectively. These low incidences may be due to an insufficient understanding and poor diagnotics of PTLD. A previous study has shown that PTLD was accompanied by extranodal infiltration and lesions invading multiple organs in 90% of cases [1].

Case 1: Hematochezia for one day. Case 2: Fever, abdominal pain and oliguria for one day.

Case 1: A 33-year-old male was admitted to the emergency department because of hematochezia.

Case 2: A 15-year-old female was admitted to the emergency because of fever, abdominal pain, and oliguria. On the second day of hospitalization, the patient’s abdominal pain became aggravated, and her body temperature increased to 39°C. Physical examination showed whole abdominal pressure pain and signs of peritoneal irritation.

Case 1: The patient was diagnosed with glomerulonephritis 7 years ago, and his creatinine level kept slowly increasing over years. Eventually, the disease progressed into end-stage renal disease 6 mo ago, and the patient received renal transplant for a donor of cardiac death. The induction immunosuppressive therapy included antithymocyte globulin (ATG) 50 mg/d on day 0 - day 3 postoperatively, tacrolimus (Tac) + mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) + prednisone acetate (Pred) for maintenance treatment. Two months ago, the patient was admitted to the emergency department because of a sore throat and fever.

Case 2: The patient underwent renal transplantation because of polycystic kidney disease 1 year ago. The induction immunosuppressive therapy included ATG at 50 mg/d on day 0 - day 3. The postoperative immunosuppressive therapy consisted of cyclosporine A (CsA) + MMF + Pred.

None for both cases.

Case 1: Right cervical lymphadenopathy, an enlarged left tonsil. Case 2: Physical examination showed whole abdominal pressure pain (+) and signs of peritoneal irritation (+).

Case 1: White blood cell count was 2.41 × 109/L, neutrophil count was 1.19 × 109/L, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) DNA load was 5.22 × 104 IU/mL, creatinine level was 132 μmol/L. Biopsy of the right anterior cervical lymph node showed that the lymph node was destroyed and some cells had multiple nucleoli (Figure 1). Immunohistochemical staining showed CD21-, CD20+, Pax-5+, CD79a-, CD3-, a tumor regional KI-67 proliferation index > 50%, CD10-, Bcl-6+, Bcl-2+ 80%, C-myc+ 10%, Mum-1+, CD5-, CD15 not significant (NS), CD30+, Pax-5+, Oct-2 NS, and Bob-1+. In situ hybridization showed EBV-encoded small RNAs (EBERs) at a level of > 200/high-power field (HPF).

Case 2: A routine blood test at the emergency department showed white blood cell count 4.35 × 109/L, neutrophil ratio 89.0%, hemoglobin concentration 70 g/L, platelet count 333 × 109/L, C-reactive protein concentration 189.70 mg/L, procalcitonin concentration 3.51 ng/mL, and creatinine level 111 μmol/L. Immunohistochemistry showed CD56(-), CD38(+), KI-67 (75%+), CD30 (+), CD31 blood vessel (+), CD5(-), CD20 (+), MUM-1(+), Bcl-6(-), cyclin D-1(-), Bcl-2(+), CD10(-), C-myc 20-30%(+), EBER (+) > 200/HPF, CD21(-), and PAX-5(+).

Case 1: Colonoscopy showed a large ulcer on the sigmoid colon, 30 cm from the anus, and the patient was diagnosed with EBV-positive post-transplant diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by pathological biopsy (Figure 2). Abdominal enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan showed lymphadenectasis in the abdominal cavity, retroperitoneum, right external iliac artery region, and right inguinal region.

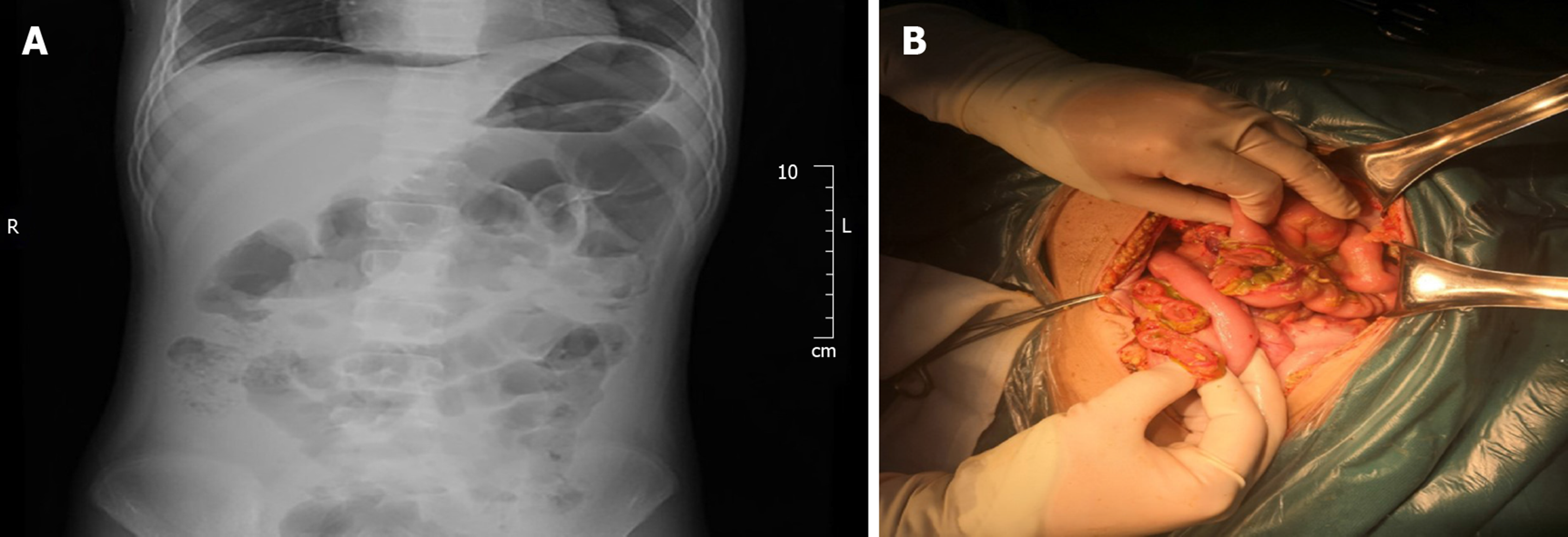

Case 2: CT scan showed pelvic effusion, splenomegaly, and multiple lymphadenectasis in the abdominal cavity. A plain abdominal radiograph showed a perforation of the digestive tract.

Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder (monomorphic large B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma).

Post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder (monomorphic non-Hodgkin’s EBV-positive diffuse large B-cell lymphoma).

After confirmation of lymphoma, we immediately changed immunosuppressive therapy to 0.5 mg Tac BID + 10 mg Pred once a day. Additionally, the patient received 375 mg/m2 rituximab targeted treatment once a week.

The patient underwent urgent exploratory laparotomy. During the surgery, approximately 1200 mL pale-yellow purulent effusion in the abdominal cavity, intestinal adhesion, multiple intestinal perforations at 20-40 cm from the ligament of Treitz, aerocolia, and multiple lymphadenectasis at the mesenteric root were found. The patient underwent enterolysis, partial resection of the small intestine, and small intestine anastomosis. After the surgery, Pred and MMF were discontinued and injection of 100 mg/d CsA was maintained.

After four rounds of rituximab treatment, imaging assessment showed reduced accumulation of the radionuclide in the cervical lymph nodes, transplanted kidney, retroperitoneum, and inguinal lymph nodes compared to pre-treatment. Colonoscopy showed intestinal ulcer scar formation. Pathological biopsy did not find any heterocyst. Renal function was improved, and the creatinine level was maintained at 110-120 μmol/L, which might be related to the alleviation of lesions in the transplanted kidney (Figure 3).

After 2 days of fasting, water restriction, and nutritional support, the patient’s condition improved, renal function and urine volume recovered to normal. The patient had received four cycles of rituximab treatments. Clinical symptoms and imaging both showed alleviation of lesions. The function of the transplanted kidney was stable, and the creatinine level was between 50 and 60 μmol/L (Figures 4, 5).

PTLD is highly heterogeneous and includes a group of diseases ranging from benign lymphocytosis to malignant invasive lymphomas. PTLD after renal transplantation is rare, with an incidence of approximately 1% according to overseas studies, which is only second to skin cancer. However, in China, the dominant tumors after kidney transplantation are urothelial carcinomas, and experience in the diagnosis and treatment of PTLD is obviously insufficient. PTLD is accompanied by extranodal infiltration in 90% of patients, and PTLD with gastrointestinal involvement accounts for approximately 15%[2], which is probably due to the rich lymphatic system in the gastrointestinal tract. The two cases reported here were both EBV positive, and PTLD was mainly manifested with hematochezia and enterobrosis, the disease was thus highly concealed and easy to be misdiagnosed.

Currently, EBV infection is believed to be closely related to the onset of PTLD. In America and Europe, over 80% of PTLD cases are EBV positive. The main target of EBV is B cells, but EBV can also infect T cells and epithelial cells[3]. The gp350/220 protein in the envelope of EBV can bind to the CD21 molecule on the surface of B cells, facilitating EBV entrance and infection of B cells by endocytosis. The majority of infected B cells can be eliminated by CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) because of the expression of EBV nuclear antigen. However, the remaining EBV can express latent membrane protein 1 (LMP1), inducing B cells to enter the latent infection state; as a result, the cells express less virus antigen and avoid being killed by CTLs[4]. Although EBV is widespread in the population, the virus maintains a dynamic balance state with the immune system of the host, therefore, the majority of healthy people have no disease onset. However, treatment with T cell eliminating agents, such as ATG and persistent application of immune suppressants, disrupt the immune balance in kidney transplant recipients, and infected B cells are not cleared in time. EBV-specific cytotoxic T cells are mostly directed against lymphoblasts. Decreases in the number and function of T cells, due to immunosuppressive drugs such as ATG, may lead to uninhibited growth of lymphoblasts, which disrupts the balance and eventually results in the development of PTLD[5,6].

In renal transplantation, EBV-naive patients have a much higher risk of developing PTLD than latently infected patients, who are EBV seropositive at the time of transplantation. For kidney transplantations with EBV-positive donors and EBV-negative recipients, EBV load must be closely monitored for 1 year after the surgery. Some studies suggest that EBV load should be monitored every 2 wk for the first 3 mo after surgery, then, every month for the second 3 mo, and then every 3 mo for the last 6 mo. However, the evidence for preventive use of antiviral medications in this type of patients is still insufficient. When the EBV load is elevated, the dosage of immune suppressants should be reduced. Patients should be closely monitored for clinical manifestations, in combination with imaging assessments and even pathological histology examinations. However, preventive use of rituximab is not recommended. Once patients are diagnosed with PTLD, the following treatment approach should be adopted: (1) Immune suppressant dosage should be immediately reduced. However, the detailed medication options are still controversial. One study showed that switching from calcineurin inhibitors to sirolimus could suppress the tumor growth and induce necrosis at the tumor center[8]. However, some evidence has indicated that mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors might increase the risk of PTLD[9], which requires further confirmation; (2) Rituximab treatment should be started as early as possible for PTLD, which is mainly caused by B-cell proliferation. A treatment plan combining rituximab with cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine and Pred (R-CHOP), should be used for patients whose symptoms are not alleviated by monotherapy or for those who have clinically aggressive lymphomas. Sequential treatment with 4 cycles of rituximab followed by four 3-wk cycles of R-CHOP, led to an increased response rate of 90%. The median overall survival was 6.6 years, which is better than that in 3 prospective trials, which applied 4 to 8 cycles of rituximab monotherapy[4,7]. Therefore, sequential treatment with rituximab and CHOP can improve the efficacy and alleviate CHOP chemotherapy-related side effects; (3) Because the pathogenesis of PTLD involves an insufficient killing capacity of T cells, in recent years, patient-derived EBV-specific cytotoxic T cells have been used to treat PTLD after T cell proliferation in vitro and transfusion back to the patients, allowing achievement of a decent efficacy. However, it is difficult to isolate sufficient amounts of EBV-specific cytotoxic T cells from monocytes in the peripheral blood because of the bone marrow suppression in transplant patients. Therefore, a research also selected donors with matching human leukocyte antigen as the source of specific CTLs, which resulted in complete or partial remission in 60%-80% of patients[10]. However, treatment by infusion of EBV-specific cytotoxic T cells is slow, and the cells are difficult to prepare, which limits their clinical application; and (4) In the case of PTLD-induced enterobrosis, gastrointestinal bleeding can be treated by surgery.

In addition to the treatments mentioned above, local radiotherapy targeting PTLD, antiviral treatment targeting EBV, mTOR receptor blockers, and interferon-α and interleukin-6 monoclonal antibody treatments have all been reported, but their efficacies are not clear[11]. Because PTLD may involve multiple organs, its symptoms are not specific, which leads to tremendous difficulty in clinical diagnosis. Although application of rituximab has significantly improved the prognosis of PTLD, with the treatment response rate as high as 52%, patients’ long-term survival is still low, and the 1-year and 3-year survival rates are 48% and 30%, respectively[12].

The main manifestations in our cases were hematochezia and enterobrosis. The final diagnosis relied on pathological biopsy, and both patients responded well to treatment. In the future, with better understanding of the disease and an improved diagnosis, the incidence of PTLD may increase. Once patients are confirmed with PTLD, they should be treated as soon as possible to control disease progression. Further investigations are required for more effective treatments.

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, Research and Experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Sheashaa HA S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: MedE-Ma JY E-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Nijland ML, Kersten MJ, Pals ST, Bemelman FJ, Ten Berge IJ. Epstein-Barr Virus-Positive Posttransplant Lymphoproliferative Disease After Solid Organ Transplantation: Pathogenesis, Clinical Manifestations, Diagnosis, and Management. Transplant Direct. 2016;2:e48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Fu L, Xie J, Lin J, Wang J, Wei N, Huang D, Wang T, Shen J, Zhou X, Wang Z. Monomorphic Post-transplant Lymphoproliferative Disorder After Kidney Transplantation and Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation: Clinicopathological Characteristics, Treatments and Prognostic Factors. Indian J Hematol Blood Transfus. 2017;33:492-499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hertig A, Zuckermann A. Rabbit antithymocyte globulin induction and risk of post-transplant lymphoproliferative disease in adult and pediatric solid organ transplantation: An update. Transpl Immunol. 2015;32:179-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Kitajima K, Sasaki H, Koike J, Nakazawa R, Sato Y, Yazawa M, Tsuruoka K, Kawarazaki H, Imai N, Shirai S, Shibagaki Y, Chikaraishi T. Asymptomatic post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder diagnosed at one year protocol renal allograft biopsy. Nephrology (Carlton). 2014;19 Suppl 3:42-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Li J, Liu Y, Wang Z, Hu X, Xu R, Qian L. Multimodality imaging features, treatment, and prognosis of post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder in renal allografts: A case report and literature review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2018;97:e0531. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Martinez OM, Krams SM. The Immune Response to Epstein Barr Virus and Implications for Posttransplant Lymphoproliferative Disorder. Transplantation. 2017;101:2009-2016. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Mohri T, Ikura Y, Hirakoso A, Okamoto M, Hishizawa M, Takaori-Kondo A, Kato S, Nakamura S, Yoshimura K, Okabe H, Iwai Y. Classical Hodgkin lymphoma type post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorder in a kidney transplant recipient: a diagnostic pitfall. Int J Hematol. 2018;108:218-227. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ferreira H, Bustorff M, Santos J, Ferreira I, Sampaio S, Salomé I, Bastos J, Bergantim R, Príncipe F, Pestana M. Post-transplant Lymphoproliferative Disorder: A Single-Center Experience. Transplant Proc. 2015;47:981-984. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kirk AD, Cherikh WS, Ring M, Burke G, Kaufman D, Knechtle SJ, Potdar S, Shapiro R, Dharnidharka VR, Kauffman HM. Dissociation of depletional induction and posttransplant lymphoproliferative disease in kidney recipients treated with alemtuzumab. Am J Transplant. 2007;7:2619-2625. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in RCA: 152] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Amorim Pellicioli AC, Luciano AA, Rangel AL, de Oliveira GR, Santos Silva AR, de Almeida OP, Vargas PA. Epstein-Barr virus (EBV)--associated posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorder appearing as mandibular gingival ulcers. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2016;121:e80-e86. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Windpessl M, Burgstaller S, Kronbichler A, Pieringer H, Kalev O, Karrer A, Wallner M, Thaler J. Progressive Multifocal Leukoencephalopathy Following Combined Rituximab-Based Immune-Chemotherapy for Post-transplant Lymphoproliferative Disorder in a Renal Transplant Recipient: A Case Report. Transplant Proc. 2018;50:881-883. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Cheung CY, Ma MKM, Chau KF, Chak WL, Tang SCW. Posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorders in kidney transplant recipients: a retrospective cohort analysis over two decades in Hong Kong. Oncotarget. 2017;8:96903-96912. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |