Published online Oct 6, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i19.3069

Peer-review started: June 29, 2019

First decision: July 31, 2019

Revised: August 28, 2019

Accepted: September 9, 2019

Article in press: September 9, 2019

Published online: October 6, 2019

Processing time: 95 Days and 10 Hours

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a rare group of disorders of immune dysregulation characterized by clinical symptoms of severe inflammation. There are basically two types of clinical scenarios: Familial HLH and sporadic HLH. It is thought that the syndrome is implicated in the development of infections, malignancies, and autoimmune diseases. HLH, whether primary or secondary, is characterized by activated macrophages in hematopoietic organs, hepatosplenomegaly, cytopenia, and fever; however, HLH complicated with polyserositis (PS) has never been reported.

We present a case of fever in a 46-year-old previously healthy Chinese woman complicated by pericardial, pleural, and abdomen effusions. She had no contact with sick individuals, recent travel, illicit drug use, or new sexual contacts. She did not consume alcohol or tobacco and lacked a family history of other diseases. Antibiotics were prescribed for suspected infection, and acute liver injury subsequently occurred. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography showed mild pericardial effusion, pleural effusion, hepatosplenomegaly, and a large amount of ascites. A full blood count revealed leukopenia and thrombocytopenia. Increased ferritin and triglyceride levels were observed. The test for Epstein-Barr (EB) virus DNA was positive. This suggests that EB virus replication and EB virus infection existed. Additional studies showed hemophagocytosis in bone marrow biopsy specimens. The patient’s condition progressed rapidly. After providing symptomatic support treatment, eliminating immune stimuli, and administering comprehensive cyclosporine and dexamethasone treatment, the patient’s condition continued to progress, and the patient’s family members decided to stop treatment; the patient subsequently died.

This case shows the significance of considering HLH as part of the evaluation of unexplained fever and PS of unknown origin.

Core tip: Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is a rare disorder of the mononuclear phagocytic system, characterized by systemic proliferation of non-neoplastic histiocytes. HLH, whether primary or secondary, is characterized by activated macrophages in hematopoietic organs, hepatosplenomegaly, cytopenia, and fever, but complicated with polyserositis (PS) is rare. We present a case of HLH in a 46-year-old Chinese woman complicated by pericardial, pleural, and abdomen effusions. It could be important to focus attention on PS in order to broaden our outlook and expand our train of thought.

- Citation: Zhu P, Ye Q, Li TH, Han T, Wang FM. Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis complicated by polyserositis: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(19): 3069-3073

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i19/3069.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i19.3069

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH), also known as hemophagocytic syndrome, is a rare and lethal disease of the reactive mononuclear macrophage system. HLH is an uncontrolled hematological disorder characterized by acute activation of macrophages and lymphocytes, resulting in a strong pathologic immune response[1]. It is not an independent disease but a group of clinical syndromes involving multiple organs, including the liver, spleen, lymph nodes, bone marrow, brain, and lungs[2]. HLH can be related to a wide variety of underlying diseases, can develop at any age, and can occur as an acquired or genetic disorder.

A 46-year-old woman presented with fever, asthenia, and abdominal distention for more than 20 days.

Twenty days before the present admission, the patient’s initial clinical symptom was fever, and then she developed a sore throat. She went to a hospital, and her objective examination was negative. She had a diagnosis of upper airway infection and was prescribed antibiotic therapy, initially with levofloxacin. One week after the first hospital consultation, the patient returned with an ongoing fever, asthenia, and abdominal distention. Laboratory results included a white blood cell count of 3.45 × 109/L, platelet (PLT) count of 41 × 109/L, and hemoglobin (HGB) level of 123 g/L, indicating a decreased PLT count. On the following day, she was admitted to our hospital for close examination and treatment.

She had no chronic illnesses.

She had no new sexual contacts, recent travel, sick contacts, or illicit drug use. She had no history of alcohol intake or smoking, and lacked a family history of other diseases.

Her vital signs included a blood pressure of 105/62 mmHg, pulse rate of 89 beats/min, maximum temperature of 37.6 °C, and oxygen saturation of 98% on room air. The sclera of her eyes was yellow. On chest auscultation, respiratory sounds in the bilateral lungs were weak. She had a distended abdomen with a shifting dullness on percussion.

A full blood count revealed bicytopenia with leukopenia and thrombocytopenia. The test for the Epstein-Barr (EB) virus antibody was positive. Repeated blood and urine cultures were negative. Her laboratory results of alanine aminotransferase (207 U/L), aspartate aminotransferase (244 U/L), total bilirubin (7.68 mg/dL), serum albumin (ALB: 33.6 g/L), and prothrombin time (PT; 52%) indicated liver injury. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 46 mm/h. An increased ferritin level of 997 mg/dL was observed. The lactate dehydrogenase level was elevated to 3278 U/L. The fibrinogen level was reduced to < 1.52 g/L. The triglyceride level was elevated to 2.45 mmol/L. The test for the EB virus antibody was negative; however, the level of EB virus DNA was 1.56 × 107. Immunologic examinations were normal. Hepatitis markers were negative. The T-cell spot test for tuberculosis infection was negative. All investigations resulted from the hospital admission (Table 1). The cytology test results of the ascites and pleural fluid were negative. The pleural fluid and ascites were exudative according to Light’s criteria, and the cultures were negative.

| Hematology | Biochemistry | Virus marker |

| WBC 2.11 × 109/L | AST 244 U/L | HAV IgM - |

| RBC 4.07 × 1012/L | ALT 207 U/L | HBsAg - |

| Hb 112g/L | ALB 33.6 g/L | HBcAb + |

| HCT 38.4% | AKP 335 U/L | HCVAb - |

| MCV 94.9 | γ-GT 104 U/L | HEVAb - |

| PLT 48 × 109/L | Ceruloprotein 27.2 mg/L | CMV IgM - |

| Rtc 4.42% | ChE 2976 U/L | EBV IgM - |

| LDH 3278 U/L | EB DNA 1.56 × 107 | |

| Coagulation | Ferritin 997 mg/dL | T-SPOT - |

| PT 52% | TB 7.68 mg/dL | Serology |

| PT-INR 1.2 | DB 6.26 mg/dL | ANA - |

| APTT 33.6 s | CRP 15.2 μg/mL | ASMA - |

| Fibrinogen 1.52 g/L | FBS 4.9 mmol/L | LKM-1 - |

| D-dimer 0.78 mg/mL | TG 2.45 mmo/L | AMA - |

| CHO 5.48 mmo/L | HLA-DR - | |

| ESR 46 mm/h | NH3 20 μmol/L | AMA-M2 - |

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) showed mild pericardial effusion, pleural effusion, hepatosplenomegaly, and a large amount of ascites. Color Doppler echocardiography showed pericardial effusion and normal left ventricular systolic function.

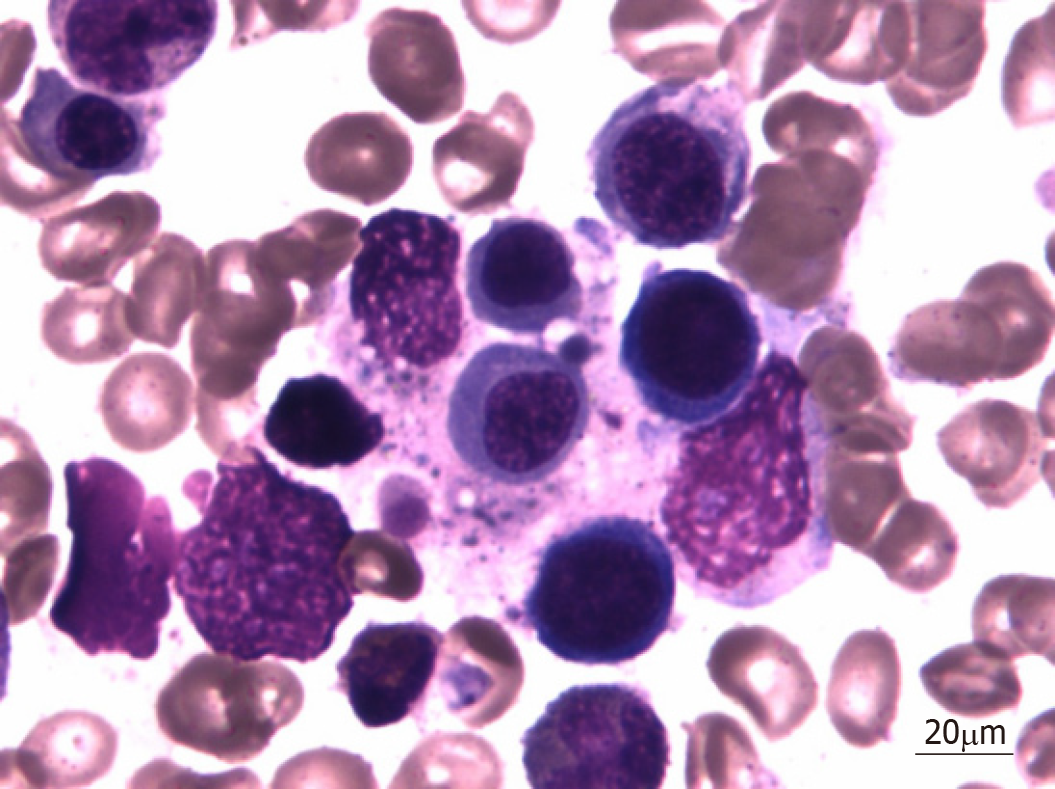

On hospital day 7, bone marrow aspiration was performed, and hemophagocytosis was observed in the bone marrow (Figure 1).

After liver protective and diuretic treatments, the serous effusion disappeared quickly. The patient was treated based on a working diagnosis of HLH. Treatment was initiated based on the HLH-2004 protocol[3] with 20 mg of dexamethasone and 150 mg of cyclosporine twice daily for 2 wk, but her condition continued to worsen. Laboratory findings demonstrated a drop in her HGB and PLT levels and worsening liver function test results.

Her relatives chose not to pursue further treatment. She died shortly after leaving the hospital.

This is an interesting case because it involves a patient with HLH who had an onset of polyserositis (PS). HLH was first reported by Risdall et al[4] in 1939. It is a progressive aggravation of multiple organs with multiple system involvement in immune dysfunction. It can be divided into two types: Primary and secondary[5]. Primary HLH is an autosomal recessive hereditary disease. Secondary HLH is more common in adolescents and adults than primary HPS. Secondary HPS is often caused by infections (bacteria, viruses, and parasites), autoimmune diseases, hematological malignancies, or hematopoietic stem cell transplantation[6]. In addition, HIV and drug use can also cause the disease[6]. It has been reported that the prognosis of HLH induced by bacterial infection is better than that of HLH induced by other factors, and the prognosis of patients with HLH induced by infection with the EB virus is the worst[7]. The mortality of patients with HLH secondary to cancer is almost 100%[8]. HLH can also be classified into infectious-related HLH, tumor-related HLH, and autoimmune-related HLH according to the etiology. Trizzino et al[9] and other studies show that HLH cannot be absolutely divided into primary and secondary HLH. Secondary HLH is also related to the relationship between host-related genotypes and phenotypes. HLH is a disease that is associated with host gene deletion or polymorphism and the concurrent existence of specific immune stimuli.

Diagnosis of secondary HLH necessitates the fulfillment of five of the following eight criteria[3]: fever, splenomegaly, cytopenia involving two of three cell lineages in the peripheral blood, hypertriglyceridemia, ferritin > 500 ng/mL, hemophagocytosis seen in the bone marrow or lymph nodes, low natural killer cell activity, and a soluble interleukin-2 receptor level > 2400 U/mL. HLH, whether primary or secondary, is characterized by activated macrophages in hematopoietic organs, hepatosplenomegaly, cytopenia, and fever; however, HLH complicated with PS is rare. PS is the inflammation of different serous membranes with effusion. Although the causes of PS are being uncovered, such as infections, autoimmune reactions, toxins, metabolic malfunctioning, autoinflammatory reactions, neoplastic diseases, or endocrine diseases, the etiology of PS remains unknown in a high percentage of patients[10]. PS refers to the presence of effusion in two or more serous cavities, usually caused by malignant tumors or tuberculosis, followed by connective tissue diseases, cirrhosis, and cardiac insufficiency. It can also be seen in patients with acute pancreatitis, diabetes, Sean’s syndrome, etc. The patient was a middle-aged woman with acute onset and manifestations of fever, liver damage, and splenomegaly. Laboratory tests showed cytopenia, hypertriglyceridemia, a ferritin level > 500 ng/mL, and hemophagocytosis in the bone marrow. The diagnosis of HLH was clear, but HLH complicated with PS is rare. When diagnosing this patient, the following diseases were excluded: (1) Malignant tumors: This patient had an acute onset and tested negative for tumor markers. Abdominal enhanced CT showed no abnormal enlargement or space occupancy of the abdominal lymph nodes. After symptomatic diuretic treatment, the multiple serous effusion disappeared rapidly, which did not support the diagnosis of malignant tumors; (2) Autoimmune disorders: The patient was a middle-aged woman with fever, liver injury, and multiple serous effusion; the absence of arthralgia, oral ulcers, photosensitivity, and other symptoms, abnormal immunoglobulin, abnormal complement, abnormal autoantibodies, and autoimmune liver disease antibodies can exclude the possibility that autoimmune diseases are causing the pleural effusion and ascites; and (3) Tuberculosis: The patient had no history of tuberculosis. The specific T lymphocyte test for tuberculosis infection was negative. Without anti-tuberculosis treatment, the serous effusion disappeared quickly, and her body temperature was normal, excluding tuberculosis. Although the patient had hypoproteinemia (33.6 g/L), the decrease in the level of ALB was not directly proportional to the volume of effusion. After liver protective and diuretic treatments, the patient's multiple serous effusion disappeared quickly. Therefore, the formation of multiple serous effusion could not be fully explained by hypoproteinemia alone. The absence of identifiable infective or neoplastic etiologies in our patient suggests a reaction to the EB virus. An infection can trigger an individual with an underlying immune dysregulation to express an overt autoimmune disease.

In summary, this is the report of a rare case of HLH complicated with PS. It could be important to focus attention on PS in order to broaden our outlook and expand our train of thought.

The authors thank Dr. Xi-Feng Dong at the Department of Hematology, General Hospital of Tianjin Medical University for her help.

| 1. | Wysocki CA. Comparing hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in pediatric and adult patients. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017;17:405-413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Wang Y, Wang Z. Treatment of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Curr Opin Hematol. 2017;24:54-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Henter JI, Horne A, Aricó M, Egeler RM, Filipovich AH, Imashuku S, Ladisch S, McClain K, Webb D, Winiarski J, Janka G. HLH-2004: Diagnostic and therapeutic guidelines for hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2007;48:124-131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3075] [Cited by in RCA: 3781] [Article Influence: 199.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 4. | Risdall RJ, McKenna RW, Nesbit ME, Krivit W, Balfour HH, Simmons RL, Brunning RD. Virus-associated hemophagocytic syndrome: a benign histiocytic proliferation distinct from malignant histiocytosis. Cancer. 1979;44:993-1002. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Freeman HR, Ramanan AV. Review of haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96:688-693. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kleynberg RL, Schiller GJ. Secondary hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults: an update on diagnosis and therapy. Clin Adv Hematol Oncol. 2012;10:726-732. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Imashuku S, Hyakuna N, Funabiki T, Ikuta K, Sako M, Iwai A, Fukushima T, Kataoka S, Yabe M, Muramatsu K, Kohdera U, Nakadate H, Kitazawa K, Toyoda Y, Ishii E. Low natural killer activity and central nervous system disease as a high-risk prognostic indicator in young patients with hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis. Cancer. 2002;94:3023-3031. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Daver N, Kantarjian H. Malignancy-associated haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in adults. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:169-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Trizzino A, zur Stadt U, Ueda I, Risma K, Janka G, Ishii E, Beutel K, Sumegi J, Cannella S, Pende D, Mian A, Henter JI, Griffiths G, Santoro A, Filipovich A, Aricò M; Histiocyte Society HLH Study group. Genotype-phenotype study of familial haemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis due to perforin mutations. J Med Genet. 2008;45:15-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 93] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Losada I, González-Moreno J, Roda N, Ventayol L, Borjas Y, Domínguez FJ, Fernández-Baca V, García-Gasalla M, Payeras A. Polyserositis: a diagnostic challenge. Intern Med J. 2018;48:982-987. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See:

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, Research and Experimental

Country of origin: China

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Carter WG S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: Wang TQ E-Editor: Qi LL