Published online Sep 6, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i17.2477

Peer-review started: April 8, 2019

First decision: June 28, 2019

Revised: July 23, 2019

Accepted: July 27, 2019

Article in press: July 27, 2019

Published online: September 6, 2019

Processing time: 154 Days and 5.2 Hours

Liver resection surgery has advanced greatly in recent years, and the adoption of fasttrack programs has yielded good results. Combination anesthesia (general anesthesia associated to epidural analgesia) is an anesthetic-analgesic strategy commonly used for the perioperative management of patients undergoing surgery of this kind, though there is controversy regarding the coagulation alterations it may cause and which can favor the development of spinal hematomas.

To study the postoperative course of liver resection surgery, an analysis was made of the outcomes of liver resection surgery due to colorectal cancer metastases in our centre in terms of morbiditymortality and hospital stay according to the anesthetic technique used (general vs combination anesthesia).

A prospective study was made of 61 colorectal cancer patients undergoing surgery due to liver metastases under general and combination anesthesia between January 2014 and October 2015. The patient characteristics, intraoperative variables, postoperative complications, evolution of hemostatic parameters, and stay in intensive care and in hospital were analyzed.

A total of 61 patients were included in two homogeneous groups: general anesthesia (n = 30) and combination anesthesia (general anesthesia associated to epidural analgesia) (n = 31). All patients had normal coagulation values before surgery. The international normalized ratio (INR) in both the general and combination anesthesia groups reached maximum values at 2448 h (mean 1.37 and 1.45 vs 1.39 and 1.41, respectively), followed by a gradual decrease. There was less intraoperative bleeding in the combination anesthesia group (769 mL) than in the general anesthesia group (1200 mL) (P < 0.05). Of the 61 patients, 38.8% in the general anesthesia group experienced some respiratory complication vs 6.6% in the combination anesthesia group (P < 0.001). The time to gastrointestinal tolerance was significantly correlated to the type of anesthesia, though not so the stay in critical care or the time to hospital discharge.

Epidural analgesia in liver resection surgery was seen to be safe, with good results in terms of pain control and respiratory complications, and with no associated increase in complications secondary to altered hemostasis.

Core tip: This is a study of morbiditymortality and hospital stay according to the anesthetic technique used (general vs combination anesthesia) in liver resection surgery in patients with colorectal cancer metastases. Epidural analgesia in liver resection surgery was seen to be safe, with good results in terms of pain control and respiratory complications, and with no associated increase in complications secondary to altered hemostasis. The time to gastrointestinal tolerance was significantly correlated to the type of anesthesia, though not so the stay in critical care or the time to hospital discharge.

- Citation: Perez Navarro G, Pascual Bellosta AM, Ortega Lucea SM, Serradilla Martín M, Ramirez Rodriguez JM, Martinez Ubieto J. Analysis of the postoperative hemostatic profile of colorectal cancer patients subjected to liver metastasis resection surgery. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(17): 2477-2486

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i17/2477.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i17.2477

There is currently enough experience to consider liver resection as the treatment of choice for some colorectal cancer patients with liver metastases. Combination anesthesia (general anesthesia associated to epidural analgesia) is an anestheticanalgesic strategy commonly used for the perioperative management of liver surgery patients. Its inclusion in fasttrack liver surgery protocols has yielded good results in terms of morbidity and hospital stay[1-3]. However, there is some controversy regarding the use of combination anesthesia in liver resection surgery, due to the probable coagulopathy[4] that accompanies procedures of this kind, and its complications (e.g., spinal hematoma). The anesthetist therefore must weigh the advantages of the epidural catheter against the possible complications associated with its placement and removal.

The present study examines the hemostatic changes in patients undergoing liver resection due to colorectal cancer metastases, their course, and whether the extent of liver resection is a predictor of postoperative coagulopathy.

Assessment is also made of intraoperative bleeding, associated respiratory complications, stay in critical care and time to hospital discharge according to the anesthetic technique used (general vs combination anesthesia).

Following approval by the Ethics Committee, a prospective observational study was carried out involving 61 colorectal cancer patients undergoing surgery due to liver metastases in a tertiary hospital between January 2015 and June 2016. All patients gave their consent for inclusion in the study. In addition to demographic variables [age, gender and body mass index (BMI)], we recorded anesthetic risk, the patient medical history, previous continuous treatment with antiplatelet drugs or antico-agulants, preoperative hemostasis, type of liver resection (major, defined as the resection of ≥ 3 couinaud segments, or minor, defined as the resection of ≤ 2 segments), type of anesthesia (general or combination anesthesia), intraoperative central venous pressure (CVP), hepatic vascular exclusion, surgery time, estimated blood loss, intra and postoperative blood products administered, weight of the surgical piece and hemostasis values at the end of surgery and after 24, 48, 72, 96 and 120 h. All surgeries were performed by the same surgical team with extensive experience in liver surgery. A first descriptive analysis was made of the preoperative variables, followed by an analysis of the behaviour of the postoperative hemostatic parameters over time.

Rocuronium was used as neuromuscular blocker in all patients, and sugammadex was used as reversal agent at the end of surgery where required.

The statistical analysis of the data was carried out using R Statistical Programming Language®-Project for Statistical Computing® version 2.15.0 for MS Windows XP® and Linux Fedora 16 Kernel 3.4.111[5].

Of the total patients, 30 were subjected to general anesthesia and 31 to combination anesthesia (general anesthesia plus epidural analgesia).

There were no statistically significant differences between the groups in terms of the preoperative variables, with the exception of BMI (Table 1).

| Combination (SD) n = 30 | General (SD) n = 31 | P-value | |

| AGE | 61.7 ± 9.9 | 63.6 ± 9.7 | 0.520 |

| BMI | 24.2 ± 3.01 | 26.1 ± 3.3 | 0.111 |

| Mean blood Pressure | 91.3 ± 12.8 | 95.2 ± 15 | 0.276 |

| Creatinine | 0.86 ± 0.31 | 0.80 ± 0.27 | 0.427 |

| Glucose | 108.9 ± 24.3 | 103.9 ± 18.9 | 0.344 |

| Hemoglobin | 12.9 ± 1.51 | 13.2 ± 1.85 | 0.568 |

| Hematocrit | 38.8 ± 4.42 | 39.1 ± 5.33 | 0.817 |

| Platelets | 222 ± 77.2 | 220 ± 83.6 | 0.862 |

| INR | 0.97 ± 0.09 | 0.98 ± 0.10 | 0.885 |

| PA | 106.7 ± 17.6 | 105.1 ± 174.6 | 0.817 |

| aPTT | 29.1 ± 2.32 | 29.3 ± 2.73 | 0.976 |

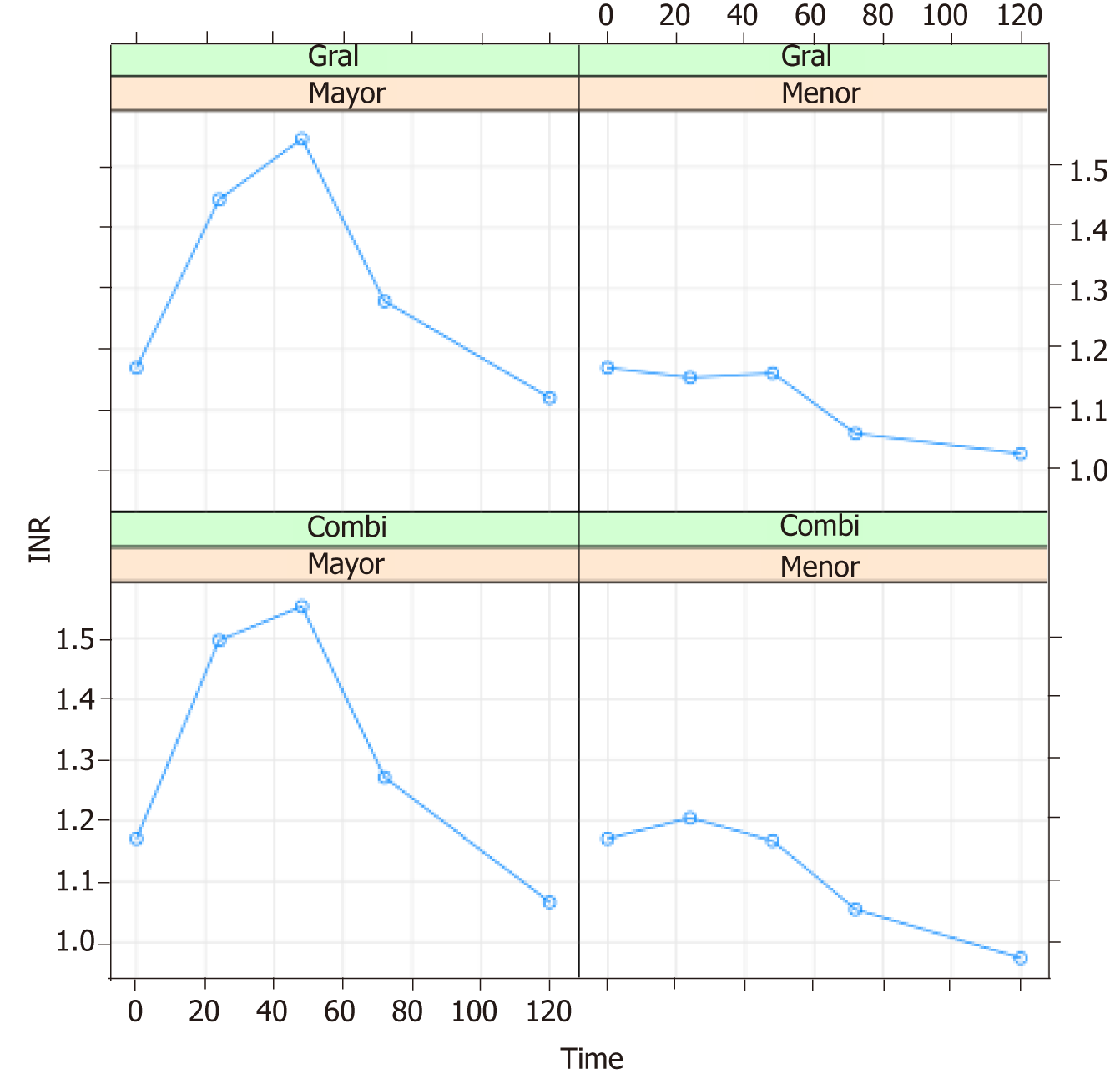

The international normalized ratio (INR) was analyzed at 0, 24, 48, 72, 96 and 120 h postsurgery (Table 2).

| Time | Anesthesia | Resection | Mean | St. error | SD |

| 0 | Combi | Major | 1.217 | 0.032 | 0.130 |

| 24 | Combi | Major | 1.516 | 0.053 | 0.219 |

| 48 | Combi | Major | 1.556 | 0.074 | 0.303 |

| 72 | Combi | Major | 1.265 | 0.042 | 0.173 |

| 120 | Combi | Major | 1.062 | 0.028 | 0.115 |

| 0 | General | Major | 1.207 | 0.035 | 0.134 |

| 24 | General | Major | 1.425 | 0.074 | 0.287 |

| 48 | General | Major | 1.542 | 0.099 | 0.385 |

| 72 | General | Major | 1.287 | 0.063 | 0.246 |

| 120 | General | Major | 1.124 | 0.052 | 0.203 |

| 0 | Combi | Minor | 1.048 | 0.049 | 0.154 |

| 24 | Combi | Minor | 1.171 | 0.057 | 0.182 |

| 48 | Combi | Minor | 1.160 | 0.098 | 0.309 |

| 72 | Combi | Minor | 1.065 | 0.074 | 0.233 |

| 120 | Combi | Minor | 0.979 | 0.048 | 0.153 |

| 0 | General | Minor | 1.142 | 0.121 | 0.271 |

| 24 | General | Minor | 1.220 | 0.027 | 0.060 |

| 48 | General | Minor | 1.174 | 0.078 | 0.175 |

| 72 | General | Minor | 1.040 | 0.071 | 0.160 |

| 120 | General | Minor | 1.018 | 0.088 | 0.197 |

The maximum INR values were recorded between 24 and 48 h after surgery in both the general anesthesia and combined anesthesia groups, followed by a gradual decrease.

The type of surgical resection was seen to influence the behaviour of the INR values over time. Figure 1 shows the values recorded at 0, 24, 48, 72 and 120 h. In the case of major liver resection, the maximum INR value (recorded at 48 hpostsurgery) was 1.54. The values subsequently decreased at 72 and 120 h (1.28 and 1.12, respectively). In the case of minor liver resection, the maximum INR value (likewise recorded at 48 h postsurgery) was 1.17. The values subsequently decreased at 72 and 120 h (1.06 and 1.01, respectively). The INR values showed statistically significant differences between major and minor resection. The mean INR curves were entered in a model including the type of resection and the type of anesthesia as INR determining factors (Figure 1).

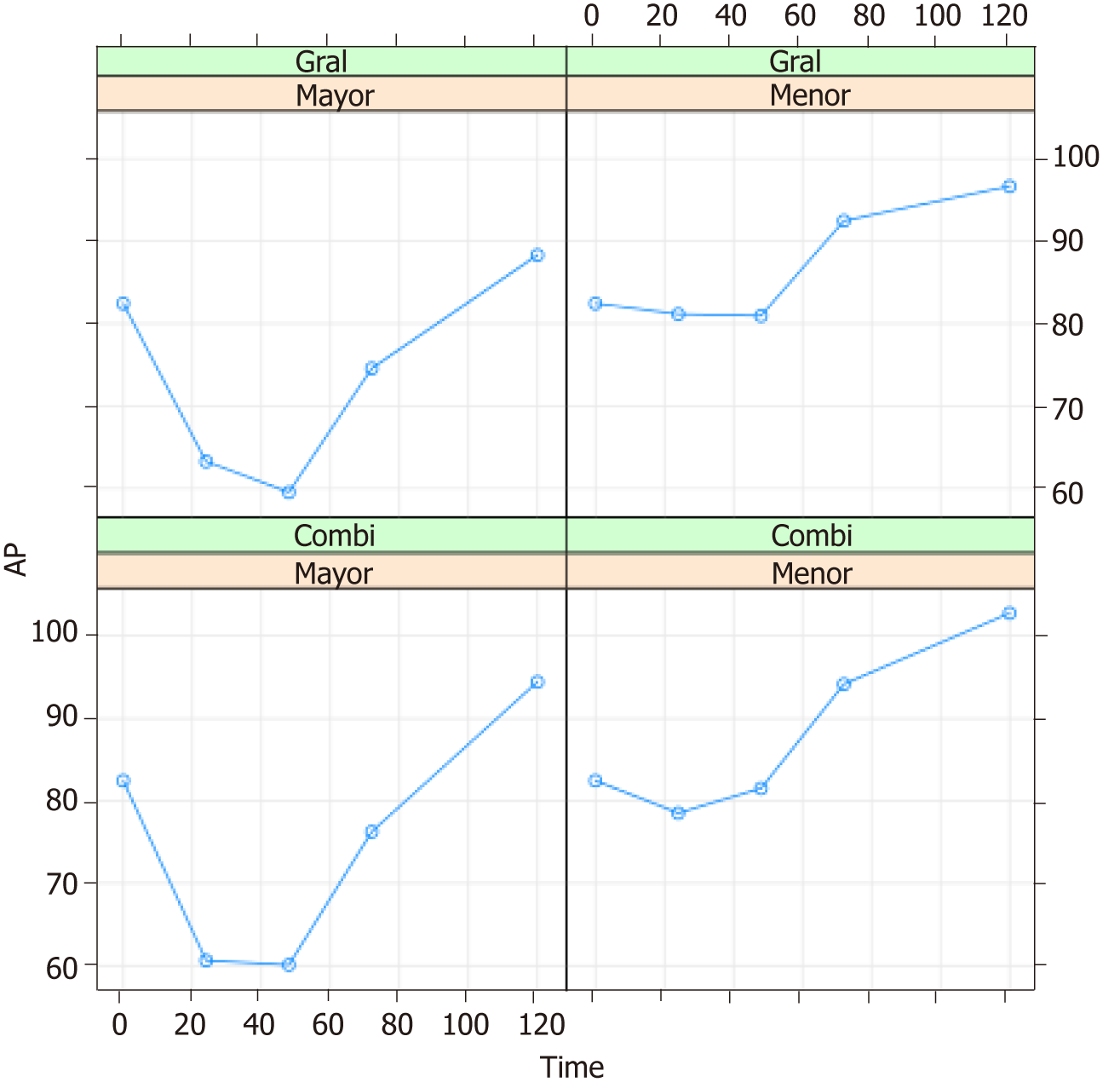

The evolution of prothrombin activity (PA) was evaluated 0, 24, 48, 72 and 120 h postsurgery (Table 3).

| Time | Anesthesia | Resection | Mean | St. error | SD |

| 0 | Combi | Major | 76.529 | 2.154 | 8.882 |

| 24 | Combi | Major | 58.824 | 2.661 | 10.973 |

| 48 | Combi | Major | 59.529 | 3.245 | 13.380 |

| 72 | Combi | Major | 76.353 | 3.240 | 13.360 |

| 120 | Combi | Major | 95.118 | 2.724 | 11.230 |

| 0 | General | Major | 78.133 | 3.275 | 12.682 |

| 24 | General | Major | 65.333 | 5.123 | 19.841 |

| 48 | General | Major | 60.200 | 5.206 | 20.164 |

| 72 | General | Major | 74.467 | 5.130 | 19.867 |

| 120 | General | Major | 87.533 | 4.916 | 19.041 |

| 0 | Combi | Minor | 95.800 | 5.781 | 18.281 |

| 24 | Combi | Minor | 81.600 | 5.053 | 15.981 |

| 48 | Combi | Minor | 82.500 | 5.905 | 18.674 |

| 72 | Combi | Minor | 94.000 | 7.335 | 23.195 |

| 120 | Combi | Minor | 101.600 | 4.960 | 15.686 |

| 0 | General | Minor | 88.800 | 8.540 | 19.097 |

| 24 | General | Minor | 75.000 | 2.408 | 5.385 |

| 48 | General | Minor | 79.000 | 6.716 | 15.017 |

| 72 | General | Minor | 92.800 | 9.019 | 20.167 |

| 120 | General | Minor | 99.000 | 9.555 | 21.366 |

Figure 2 shows the mean PA values according to the type of anesthesia and surgical resection performed. The behaviour of this parameter over time coincided with that of the INR values.

Considering the type of anesthesia and type of surgical resection, the mean blood losses were found to be 919 ml and 585 ml respectively for major and minor resection with combination anesthesia, and 1254 ml and 1116 ml respectively for major and minor resection with general anesthesia. The statistical analysis showed blood loss to be significantly related to the type of anesthesia (P = 0.008) and type of resection (P = 0.016).

Respiratory complications in turn were seen to be related to the type of anesthesia used (P = 0.003). The patients subjected to combination anesthesia suffered fewer postoperative respiratory complications (6.6%) than the patients subjected to general anesthesia (38%). Similarly, the incidence of complications was greater in the major resection group (27.3%) than in the minor resection group (17.9%) (P < 0.01).

The time from the end of surgery to gastrointestinal tolerance was related to the type of anesthesia administered: 60.4 h in the case of combination anesthesia vs 83.5 h in the case of general anesthesia (P = 0.001).

The mean time to discharge from critical care was 2.77 da and 3.74 d in the case of combination and general anesthesia, respectively, and 4.06 d and 2.32 d in the case of major and minor resection, respectively. The statistical analysis showed the number of days to discharge from critical care to be significantly associated to the type of resection (P = 0.001) but not to the type of anesthesia (P = 0.069).

In turn, the mean time to patient discharge home was 10.53 d and 7.62 d respectively for major and minor resection with combination anesthesia, and 10.47 d and 10.07 d respectively for major and minor resection with general anesthesia. The number of days to discharge was not significantly related to the type of resection (P = 0.060) or the type of anesthesia (P = 0.129). Interaction of the type of resection with the type of anesthesia yielded a pvalue close to statistical significance (P = 0.052).

Epidural analgesia is an accepted procedure in major abdominal surgery[6] .Controver-sy regarding its use in liver surgery is due to the risk of postoperative coagulation disorders[79], with spinal hematoma being the most feared complication, even in patients with normal preoperative coagulation parameters[10,11]. The possibility of coagulation disorders after liver surgery and of an increased risk of bleeding complications requires the anesthetist to weigh the advantages of placing an epidural catheter against the possible complications of catheter placement and removal[12] .

The extent of liver resection, bleeding, and the functional capacity of the remaining liver tissue can affect the magnitude and duration of the postoperative coagulation disorders, and make the appropriate timing of epidural catheter removal an important issue[13]. In coincidence with the literature, our protocol considers that an INR value of 1.55 should not be exceeded either in performing the epidural technique or in catheter removal[14], and that a minimum prothrombin activity (PA) value of 60% should be observed[15]. Other authors further lower PA to 50%[16] and INR to 1.4[17]. Stamenkovic et al[12] established a maximum INR value of 1.2 for any type of resection.

Because of this controversy, many studies involving particularly live donors and liver resection procedures in general have evaluated the course of hemostasis after liver resection surgery. Most of them[79,12-15] reported normal hemostatic control values by the fifth postoperative day. This is the reason why followup in our study was extended to the fifth day after surgery, Although, we recorded alterations in hemostasis, they proved transient, with maximum levels between 24 and 48 h after resection surgery. Our findings in this regard are consistent with those of Kim et al[14] and Siniscalchi et al[15].

In all but two cases, the hemostatic controls performed after 72 h showed the parameters to be below the normal values for removing the epidural catheter. The mentioned two patients had an epidural catheter, and the parameters were seen to have normalized 120 h after surgery, thus allowing catheter removal without complications.

The literature recommends the transfusion of fresh frozen plasma when epidural catheter removal proves mandatory and the hemostatic parameters have not been normalized[7,12,16]. None of our patients required the transfusion of this blood product, though Stamenkovic et al[12] had to perform such transfusion in a patient with an INR value of 1.5 on day four after surgery.

Possible factors underlying such coagulopathy after liver resection have been described[17], including the extent of resection, intraoperative bleeding and the functional capacity of the remaining liver tissue[12,18]. In our study, statistically significant differences were observed directly relating the type of liver resection to the subsequent development of hemostatic alterations, in coincidence with the findings of Matot et al[7]and Stamenkovic et al[12].

Liver surgery involves a high risk of intraoperative bleeding due to the anatomical characteristics of the liver, and consequently there is a greater potential need for transfusion, and higher patient morbidity and mortality[19].

Only a limited number of studies have contrasted surgical bleeding according to the type of anesthesia used. One such study was published by Page et al[20], involving patients undergoing liver resection due to any disease condition. One of the study variables was blood loss, and comparison of the epidural analgesia group (mean 709 mL) vs the nonepidural group (mean 780 ml) revealed no significant differences. Likewise, Revie et al[21], in their twoyear study of 177 patients undergoing liver resection due to any disease condition, recorded no significant differences in intraoperative bleeding according to the type of anesthesia used. In contrast to the above authors, our results indicate a mean intraoperative blood loss of 769 ml for combination anesthesia vs 1200 mL for general anesthesia the difference being statistically significant. However, since the aforementioned studies involved heterogeneous patient series, any comparative analysis entails a certain risk of bias.

Considering the characteristics of analgesia achieved with local anesthetics administered via the epidural route vs analgesia with intravenous opiates, such as possible block or attenuation of the entry of pain stimuli to the central nervous system, the literature indicates that epidural analgesia offers benefits in relation to postoperative respiratory morbidity with improved lung function and tissue oxygenation[22]. Pöpping et al[23] conducted a metaanalysis involving 58 studies with 5904 patients, of which 19 with 3504 patients analyzed respiratory complications. The authors concluded that the use of epidural analgesia was significantly associated to a decreased risk of postoperative pneumonia this being consistent with our own observations. Our study showed that 38.8% of the patients subjected to general anesthesia had some type of respiratory complication after surgery (pleural effusion, atelectasis, pneumonia), vs only 6.6% of those subjected to combination anesthesia.

However, in the only identified study reporting results different from our own, Page et al[20] described a greater number of respiratory complications (without specifying which) in their patients subjected to liver resection under epidural vs nonepidural analgesia though the differences were not significant.

Postoperative ileus implies a delay in the resumption of oral food intake and thus prolongs hospital stay[24]. One of the main factors conditioning the accelerated recovery of intestinal function after abdominal surgery is the use of epidural analgesia[25]. Studies similar to our own, such as those published by Ahmed et al[26] and Hendry et al[27], evaluating the application of a fasttrack program in liver surgery, have found gastrointestinal tolerance in all patients to be resumed 4872 h after surgery, in coincidence with our own findings. In our series, of the same size as those of Ahmed et al[26] and Hendry et al[27], the time to gastrointestinal tolerance was found to be 60.4 h on average in the combination anesthesia group vs 83.5 h in the general anesthesia group the difference being statistically significant. Our findings are likewise consistent with those of Qi et al[28], who analyzed the outcomes of fasttrack liver surgery and observed a significant decrease in the time to tolerance (64 ± 17.9 h with fasttrack surgery vs 77.0 ± 26.4 h with the classical protocol).

Abu Hilal et al[29] published one of the few studies referred to liver surgery in which patient stay in critical care was analysed. Without mentioning the type of anesthesia used, these authors compared laparoscopic surgery vs open surgery. The mean stay in the case of open surgery was about four days, which is longer than in our study. Chhibber et al[30] in turn reported a threeday stay in critical care.

Our own findings were 3.7 d of stay on average in the general anesthesia group vs 2.7 d in the combination anesthesia group this indicating a tendency towards shorter stay in the latter group, though statistical significance was not reached (P = 0.060). However, on considering the type of liver resection performed (i.e., major or minor), patient stay in critical care was seen to be significantly shorter in the minor resection group, with 2.3 d on average vs 4.3 d among the patients subjected to major liver resection.

Lastly, with regard to patient discharge home, Enhanced Recovery After Surgery protocols in liver surgery have been found to shorten the mean time to discharge (Pöpping et al[23] , Hendry et al[27] Savikko et al[31]. However, although we found combination anesthesia to result in a small reduction in time to discharge (9.3 d vs 10.3 d in the comparator group), the difference was not statistically significant. In any case, our stays were far longer than those recently published by Schultz et al[32]. These authors, after making changes to a successful protocol already implemented in 2011[2], including the administration of high dose corticosteroids before surgery (125 mg of methylprednisolone), recorded a median stay of two days for laparoscopic surgery vs four days in the case of open surgery.

In conclusion, epidural catheter placement and combination anesthesia constitute a safe alternative in patients undergoing liver resection due to colorectal cancer metastases. The coagulation alterations reach maximum levels at 24 and 48 h, with normalization of the parameters in all cases at 120 h after surgery. Statistically significant differences were observed in the evolution of the hemostatic parameters over time according to the type of liver resection involved. None of our patients required the transfusion of fresh frozen plasma for epidural catheter removal. There were no complications related to catheter placement.

There was less intraoperative bleeding in the combination anesthesia group. These patients moreover suffered fewer respiratory complications and showed a shorter time to oral tolerance.

Epidural analgesia is a well-known technique use in thoracic and abdominal surgery for its benefits in stress response, pulmonary complications. Anesthesiologists are afraid of its use in patients with potentially haemostatics disorders. Liver surgery is an example of them. In literature is well described the use of epidural analgesia in hepatic surgery and others, with different opinions. So that, we wanted to study the behaviour haemostatic profile after a particular etiology of hepatic resection, colon-rectum liver metastases. We think are patients with particular peculiarities in liver function non comparable to others disease, thus the use of epidural analgesia could be safer than in others, with greater benefits than risks.

Patient wellness, patient comfort, patient care, minimize patient stress previous and following days after surgery is one of the goals for all health professionals. So that, in literature is well published the benefits of epidural analgesia in many patients under thoracic or abdominal surgeries. Is for that we started this study, because of the discrepancies existing in use or not use epidural techniques in patients under liver surgery with potentially haemostatic postoperative disorders.

To know the behaviour of haemostatic profile following a colon-rectum metastases liver resection, to considerer if benefits of epidural analgesia are greater than risks.

The research methods (e.g., experiments, data analysis, surveys, and clinical trials) that were adopted to realize the objectives, as well as the characteristics and novelty of these research methods, should be described in detail.

We found in both minor and major hepatic resections, there was oscillation in international normalized ratio (INR) and prothrombin time till 48th postoperative hours. These variations in minor resections were never greater than INR 1.5, instead in major resections existed at 48th postoperative hours haemostatic alteration that turn to normal range before postoperative day 5. We did not use fresh frozen plasma or prothrombin complex to improve the haemostasia prior to remove an epidural catheter.

Haemostatic profile following colon-rectum hepatic metastases resection. Safety use an epidural catheter in patients under colon-rectum liver metastases resection. Benefits of epidural analgesia for patients under colon-rectum metastases liver resections are greater than risks, but if you chose use it, use it with care. Offer to anaesthesiologists another tool in anesthesia and analgesia management in patients with those characteristics.

Never is enough when in terms of health recommendations is worked. More studies are always necessary to improve and certified your studies.

| 1. | Joliat GR, Labgaa I, Petermann D, Hübner M, Griesser AC, Demartines N, Schäfer M. Cost-benefit analysis of an enhanced recovery protocol for pancreaticoduodenectomy. Br J Surg. 2015;102:1676-1683. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 72] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Schultz NA, Larsen PN, Klarskov B, Plum LM, Frederiksen HJ, Christensen BM, Kehlet H, Hillingsø JG. Evaluation of a fast-track programme for patients undergoing liver resection. Br J Surg. 2013;100:138-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Melloul E, Hübner M, Scott M, Snowden C, Prentis J, Dejong CH, Garden OJ, Farges O, Kokudo N, Vauthey JN, Clavien PA, Demartines N. Guidelines for Perioperative Care for Liver Surgery: Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Society Recommendations. World J Surg. 2016;40:2425-2440. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 456] [Cited by in RCA: 426] [Article Influence: 42.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Weinberg L, Scurrah N, Gunning K, McNicol L. Postoperative changes in prothrombin time following hepatic resection: implications for perioperative analgesia. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2006;34:438-443. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing 2012. . |

| 6. | Fawcett WJ, Baldini G. Optimal analgesia during major open and laparoscopic abdominal surgery. Anesthesiol Clin. 2015;33:65-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Matot I, Scheinin O, Eid A, Jurim O. Epidural anesthesia and analgesia in liver resection. Anesth Analg. 2002;95:1179-1181, table of contents. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Schumann R, Zabala L, Angelis M, Bonney I, Tighiouart H, Carr DB. Altered hematologic profiles following donor right hepatectomy and implications for perioperative analgesic management. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:363-368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Fazakas J, Tóth S, Füle B, Smudla A, Mándli T, Radnai M, Doros A, Nemes B, Kóbori L. Epidural anesthesia? No of course. Transplant Proc. 2008;40:1216-1217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Ruppen W, Derry S, McQuay H, Moore RA. Incidence of epidural hematoma, infection, and neurologic injury in obstetric patients with epidural analgesia/anesthesia. Anesthesiology. 2006;105:394-399. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 230] [Cited by in RCA: 203] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wu CL, Hurley RW, Anderson GF, Herbert R, Rowlingson AJ, Fleisher LA. Effect of postoperative epidural analgesia on morbidity and mortality following surgery in medicare patients. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2004;29:525-33; discussion 515-9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Stamenkovic DM, Jankovic ZB, Toogood GJ, Lodge JP, Bellamy MC. Epidural analgesia and liver resection: postoperative coagulation disorders and epidural catheter removal. Minerva Anestesiol. 2011;77:671-679. [PubMed] |

| 13. | De Pietri L, Siniscalchi A, Reggiani A, Masetti M, Begliomini B, Gazzi M, Gerunda GE, Pasetto A. The use of intrathecal morphine for postoperative pain relief after liver resection: a comparison with epidural analgesia. Anesth Analg. 2006;102:1157-1163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Kim YK, Shin WJ, Song JG, Jun IG, Kim HY, Seong SH, Sang BH, Hwang GS. Factors associated with changes in coagulation profiles after living donor hepatectomy. Transplant Proc. 2010;42:2430-2435. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 15. | Siniscalchi A, Begliomini B, De Pietri L, Braglia V, Gazzi M, Masetti M, Di Benedetto F, Pinna AD, Miller CM, Pasetto A. Increased prothrombin time and platelet counts in living donor right hepatectomy: implications for epidural anesthesia. Liver Transpl. 2004;10:1144-1149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Feltracco P, Brezzi ML, Barbieri S, Serra E, Milevoj M, Ori C. Epidural anesthesia and analgesia in liver resection and living donor hepatectomy. Transplant Proc. 2008;40:1165-1168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Shontz R, Karuparthy V, Temple R, Brennan TJ. Prevalence and risk factors predisposing to coagulopathy in patients receiving epidural analgesia for hepatic surgery. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2009;34:308-311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Gravante G, Elmussareh M. Enhanced recovery for non-colorectal surgery. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18:205-211. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 19. | Benson AB, Burton JR, Austin GL, Biggins SW, Zimmerman MA, Kam I, Mandell S, Silliman CC, Rosen H, Moss M. Differential effects of plasma and red blood cell transfusions on acute lung injury and infection risk following liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2011;17:149-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Page A, Rostad B, Staley CA, Levy JH, Park J, Goodman M, Sarmiento JM, Galloway J, Delman KA, Kooby DA. Epidural analgesia in hepatic resection. J Am Coll Surg. 2008;206:1184-1192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Revie EJ, Massie LJ, McNally SJ, McKeown DW, Garden OJ, Wigmore SJ. Effectiveness of epidural analgesia following open liver resection. HPB (Oxford). 2011;13:206-211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Block BM, Liu SS, Rowlingson AJ, Cowan AR, Cowan JA, Wu CL. Efficacy of postoperative epidural analgesia: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2003;290:2455-2463. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 723] [Cited by in RCA: 618] [Article Influence: 26.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Pöpping DM, Elia N, Marret E, Remy C, Tramèr MR. Protective effects of epidural analgesia on pulmonary complications after abdominal and thoracic surgery: a meta-analysis. Arch Surg. 2008;143:990-999; discussion 1000. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 347] [Cited by in RCA: 329] [Article Influence: 18.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Koea JB, Young Y, Gunn K. Fast track liver resection: the effect of a comprehensive care package and analgesia with single dose intrathecal morphine with gabapentin or continuous epidural analgesia. HPB Surg. 2009;2009:271986. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 63] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 25. | Werawatganon T, Charuluxananan S. WITHDRAWN: Patient controlled intravenous opioid analgesia versus continuous epidural analgesia for pain after intra-abdominal surgery. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;CD004088. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Ahmed EA, Montalti R, Nicolini D, Vincenzi P, Coletta M, Vecchi A, Mocchegiani F, Vivarelli M. Fast track program in liver resection: a PRISMA-compliant systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2016;95:e4154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Hendry PO, van Dam RM, Bukkems SF, McKeown DW, Parks RW, Preston T, Dejong CH, Garden OJ, Fearon KC; Enhanced Recovery After Surgery (ERAS) Group. Randomized clinical trial of laxatives and oral nutritional supplements within an enhanced recovery after surgery protocol following liver resection. Br J Surg. 2010;97:1198-1206. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Qi S, Chen G, Cao P, Hu J, He G, Luo J, He J, Peng X. Safety and efficacy of enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) programs in patients undergoing hepatectomy: A prospective randomized controlled trial. J Clin Lab Anal. 2018;e22434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Abu Hilal M, Di Fabio F, Teng MJ, Lykoudis P, Primrose JN, Pearce NW. Single-centre comparative study of laparoscopic versus open right hepatectomy. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15:818-823. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 73] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Chhibber A, Dziak J, Kolano J, Norton JR, Lustik S. Anesthesia care for adult live donor hepatectomy: our experiences with 100 cases. Liver Transpl. 2007;13:537-542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Savikko J, Ilmakunnas M, Mäkisalo H, Nordin A, Isoniemi H. Enhanced recovery protocol after liver resection. Br J Surg. 2015;102:1526-1532. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Schultz NA, Larsen PN, Klarskov B, Plum LM, Frederiksen HJ, Kehlet H, Hillingsø JG. Second Generation of a Fast-track Liver Resection Programme. World J Surg. 2018;42:1860-1866. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See:

Manuscript source: Unsolicited Manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country of origin: Spain

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Filippou D, Memeo R S-Editor: Cui LJ L-Editor:A E-Editor: Xing YX