Published online May 26, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i10.1149

Peer-review started: February 13, 2019

First decision: March 9, 2019

Revised: March 20, 2019

Accepted: March 26, 2019

Article in press: March 26, 2019

Published online: May 26, 2019

Processing time: 105 Days and 0.4 Hours

In patients with large stones in the common bile duct (CBD), advanced treatment modalities are generally needed. Here, we present an interesting case of a huge CBD stone treated with electrohydraulic lithotripsy (EHL) by the percutaneous approach and rendezvous endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERC) using a nasal endoscope.

A 91-year-old woman underwent ERC for a symptomatic large CBD stone with a diameter of 50 mm. She was referred to our institution after the failure of lithotomy by ERC, and after undergoing percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage. We attempted to fragment the stone by transhepatic cholangioscopy using EHL. However, the stones were too large and partly soft clay-like for lithotripsy. Next, we attempted lithotomy with ERC and cholangioscopy by the rendezvous technique using a nasal endoscope and achieved complete lithotomy. No complication was observed at the end of this procedure.

Cholangioscopy by rendezvous technique using a nasal endoscope is a feasible and safe endoscopic method for removing huge CBD stones.

Core tip: Common bile duct (CBD) stones that are very large may require choledochotomy or lithotomy. However, surgery may be contra indicated in very elderly patients, and alternate treatments are required. Recent reports indicate that electrohydraulic lithotripsy (EHL) is an effective treatment for bile duct stones. We used EHL, followed by retrograde cholangiography and the rendezvous technique via nasal endoscope to successfully treat an elderly patient with a 50 mm diameter CBD stone.

- Citation: Kimura K, Kudo K, Yoshizumi T, Kurihara T, Yoshiya S, Mano Y, Takeishi K, Itoh S, Harada N, Ikegami T, Ikeda T. Electrohydraulic lithotripsy and rendezvous nasal endoscopic cholangiography for common bile duct stone: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(10): 1149-1154

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i10/1149.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i10.1149

Common bile duct (CBD) stones are identified in up to 12% of patients with bile duct stones and are generally managed with endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERC) with endoscopic sphincterotomy (EST) for lithotomy[1]. Unfortunately, up to 15% of all CBD stones cannot be removed using standard techniques, due to the technical difficulty[2]. Extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy, laser lithotripsy, and balloon sphincteroplasty enable us to manage such complicated cases[3]. Surgical procedures, such as choledochotomy and lithotomy, are performed for cases of endoscopic failure[4]. However, surgical procedures may be contraindicated for very elderly people, such as those over 90 years old, and need careful consideration.

Recently, several reports have shown that electrohydraulic lithotripsy (EHL) is useful as a treatment for bile duct stones[5,6]. This newer procedure has not yet been established as a standard treatment, and only a few reports regarding the endoscopic treatment of bile duct stones have been published. Moreover, some cases are difficult to treat with EHL. Development of endoscopic and noninvasive lithotomy methods that avoid surgical procedures is essential for elderly patients.

Here we present the case of a patient with a huge CBD stone with a diameter of 50 mm that was successfully treated using EHL with transhepatic cholangioscopy, followed by ERC lithotomy and cholangioscopy by the rendezvous technique with a nasal endoscope.

A 91-year-old woman was admitted to another hospital because of abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and jaundice due to cholangitis with CBD stones.

Lithotomy by ERC was unsuccessful due to the large size of the stone. Thereafter, she developed strangulated CBD stones in the papilla of Vater, and underwent percutaneous transhepatic biliary drainage (PTBD) of the left lobe. She was transferred to our hospital afterward for general condition management.

The patient had a history of repeated cholangitis due to CBD stones.

She had hypertension and dementia. There is no history of her family.

She had slight jaundice upon admission, but general condition was alomost good.

Laboratory findings indicated thatwhite blood corpuscle was 5900 (reference range 3500-8400), haemoglobin 9.6 g/dL (reference range 11.3-15.2 U/L), albumin 3.0 g/dL (reference range 4.0-5.0 g/dL), aspartate aminotransferase 49 U/L (reference range 13-33 U/L), alanine aminotransferase 97 U/L (reference range 6-30 U/L), alkaline phosphatase 378 U/L (reference range 115-359 U/L), gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase 81 U/L (reference range 10-47 U/L), and C-reactive protein 0.82 mg/dL (reference range < 0.2 mg/dL).

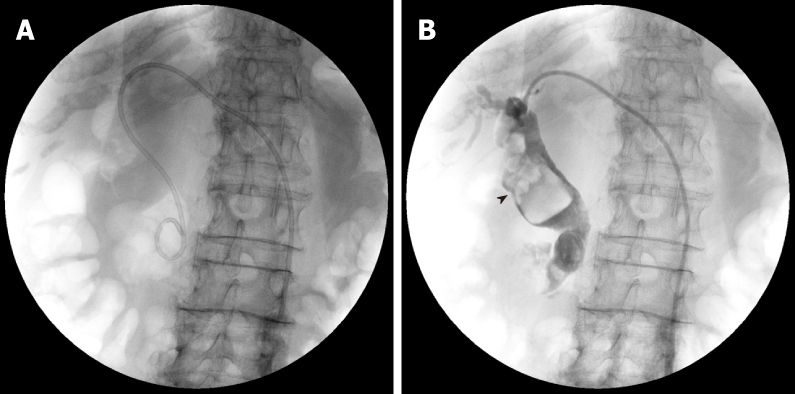

Cholangiography revealed a huge CBD stone over 50 mm in diameter (Figure 1).

The patient was diagnosed with repeat cholangitis due to CBD stones.

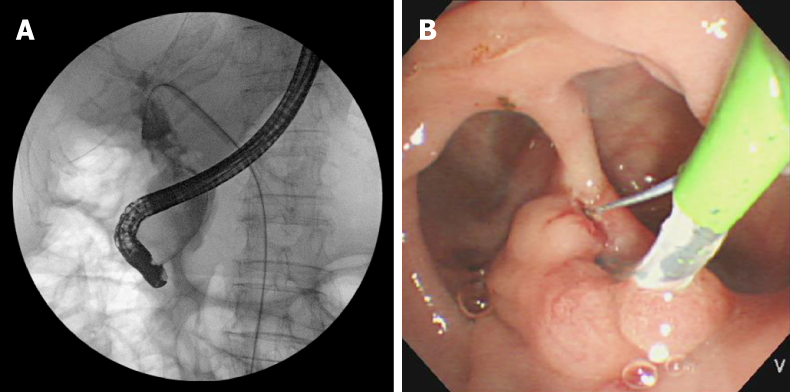

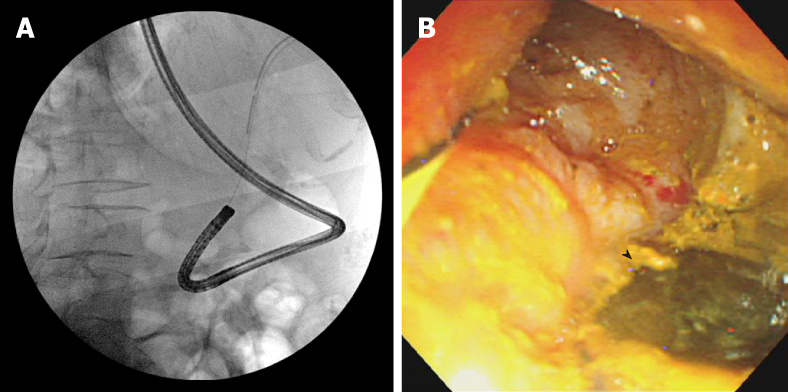

The single-stage ERC approach was not suitable for the huge CBD stone. We up-sized to a 14 Fr drainage tube and performed cholangioscopy and EHL lithotripsy (SpyGlassTM, Boston Scientific Corporation, United States) and ERC. First, EHL was performed with a cholangioscope from the percutaneous route. However, the stone was too large and partly soft clay-like in texture. We scaled down the stone by reducing the periphery with EHL, then performed ERC and EST. After cannulation into the bile duct, which was difficult due to the large periampullary diverticula, we performed the rendezvous technique (Figure 2). Lithotripsy was attempted via another crasher catheter (CrasherCatheter PowerCatchTM, MTW Endoskopie, Germany). We succeeded in breaking the CBD stone into small pieces in the bile duct, but the stone was too soft and many pieces adhered to the CBD wall. Therefore, we performed direct peroral cholangioscopy by nasal endoscope with the rendezvous technique (Figure 3). The guidewire was inserted from the PTBD route into the papilla of Vater, and was grasped with biopsy forceps via the nasal endoscope. The nasal endoscope was then inserted into the CBD along the guidewire. Complete lithotomy was accomplished by nasal endoscope with biopsy forceps and basket catheter (MiniCatchTM, MTW Endoskopie, Germany).

There is no recurrence of CBD stones after treatment for one year.

Trikudanathan et al[2] reported that in approximately 10%-15% of patients, managing biliary stones becomes hard due to hardships in accessing the bile duct (periampullary diverticula, gastrointestinal reconstructive surgery), a large number or size of stones (diameter > 15 mm), misshapen shaped stones, or location of the stones. In this case, the large diameter of the stone, its soft clay-like texture, and large parapapillary diverticula made it hard to accomplish complete lithotomy. Recently, various techniques for the treatment of intractable CBD stones have been reported. In 1982, Riemann et al[7] first introduced mechanical lithotripsy with baskets. Mechanical lithotripsy is currently the most widely used technique for fragmentation of stones and is routinely the first approach to fragment CBD stones with great advantages that are simplicity and cost-effectiveness. However, this procedure cannot be adapted to stones larger than the size of the basket, and hard and densely calcified stones resist mechanical fragmentation, resulting in an extraction failure with standard baskets.

EHL consists of a bipolar lithotripsy probe that discharges sparks with the aid of a charge generator in an aqueous medium. The sparks generated under water generate high-frequency hydraulic pressure waves, the energy of which is absorbed by nearby stones and results in their fragmentation[8]. EHL can be performed under fluoroscopic guidance by direct cholangioscopic vision. Nevertheless, in our case, we could not complete lithotomy by EHL due to the soft clay-like consistency inside the stone. Next, we attempted lithotomy with ERC after scaling down the periphery of the large stone with EHL.

Direct peroral cholangioscopy using an ultra-slim endoscope can be effective in managing patients with retained CBD stones[9]. The most profound disadvantage of peroral cholangioscopy, however, is the difficulty associated with traversing the biliary sphincter to gain access to the bile duct. This is mainly due to looping of the ultra-slim upper endoscope in the stomach or in the duodenum. To enhance the success rate of peroral cholangioscopy, specialized accessories or techniques are needed to advance the ultra-slim endoscope into the proximal biliary system[2]. We utilized the rendezvous technique to approach the bile duct by nasal endoscope.

Some studies have reported that the rendezvous technique is useful to easily access the bile duct[6,10,11]. When performing the rendezvous technique, we were easily able to access the CBD by grasping the guidewire inserted from the PTCD route using biopsy forceps.

The nasal endoscope was then inserted easily into the CBD, and used to directly visualize the CBD stones. The nasal endoscope has a wide forceps channel that accommodates insertion of biopsy forceps to grasp the guidewire, and the image from the nasal endoscope is clearer than that of the usual cholangioscope. We, therefore, find that it is easier to treat huge CBD stones using the rendezvous technique than the usual peroral cholangioscopy.

In this case, the large and soft CBD stone made lithotomy difficult. Moreover, the large parapapillary diverticula made it difficult to cannulate into the papilla of Vater and to complete lithotomy. Therefore, we derived procedures to overcome those challenges.

| 1. | Freitas ML, Bell RL, Duffy AJ. Choledocholithiasis: evolving standards for diagnosis and management. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12:3162-3167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 114] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Trikudanathan G, Navaneethan U, Parsi MA. Endoscopic management of difficult common bile duct stones. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:165-173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 80] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Li G, Pang Q, Zhang X, Dong H, Guo R, Zhai H, Dong Y, Jia X. Dilation-assisted stone extraction: an alternative method for removal of common bile duct stones. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:857-864. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Fang L, Wang J, Dai WC, Liang B, Chen HM, Fu XW, Zheng BB, Lei J, Huang CW, Zou SB. Laparoscopic transcystic common bile duct exploration: surgical indications and procedure strategies. Surg Endosc. 2018;32:4742-4748. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Otsuka Y, Kamata K, Takenaka M, Minaga K, Tanaka H, Kudo M. Electronic hydraulic lithotripsy by antegrade digital cholangioscopy through endoscopic ultrasound-guided hepaticojejunostomy. Endoscopy. 2017;49:E316-E318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kimura K, Kudo K, Kurihara T, Yoshiya S, Mano Y, Takeishi K, Itoh S, Harada N, Ikegami T, Yoshizumi T, Ikeda T. Rendezvous Technique Using Double Balloon Endoscope for Removal of Multiple Intrahepatic Bile Duct Stones in Hepaticojejunostomy After Living Donor Liver Transplant: A Case Report. Transplant Proc. 2019;51:579-584. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Riemann JF, Seuberth K, Demling L. Clinical application of a new mechanical lithotripter for smashing common bile duct stones. Endoscopy. 1982;14:226-230. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 57] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Seitz U, Bapaye A, Bohnacker S, Navarrete C, Maydeo A, Soehendra N. Advances in therapeutic endoscopic treatment of common bile duct stones. World J Surg. 1998;22:1133-1144. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kurihara T, Yasuda I, Isayama H, Tsuyuguchi T, Yamaguchi T, Kawabe K, Okabe Y, Hanada K, Hayashi T, Ohtsuka T, Oana S, Kawakami H, Igarashi Y, Matsumoto K, Tamada K, Ryozawa S, Kawashima H, Okamoto Y, Maetani I, Inoue H, Itoi T. Diagnostic and therapeutic single-operator cholangiopancreatoscopy in biliopancreatic diseases: Prospective multicenter study in Japan. World J Gastroenterol. 2016;22:1891-1901. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Noel R, Arnelo U, Swahn F. Intraoperative versus postoperative rendezvous endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography to treat common bile duct stones during cholecystectomy. Dig Endosc. 2019;31:69-76. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Yoshiya S, Shirabe K, Matsumoto Y, Ikeda T, Soejima Y, Yoshizumi T, Uchiyama H, Ikegami T, Harimoto N, Maehara Y. Rendezvous ductoplasty for biliary anastomotic stricture after living-donor liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2013;95:1278-1283. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See:

Manuscript source: Unsolicited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, Research and Experimental

Country of origin: Japan

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: de Quadros LG, Friedel D S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: A E-Editor: Xing YX