Published online May 26, 2019. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i10.1142

Peer-review started: December 29, 2018

First decision: March 10, 2019

Revised: April 23, 2019

Accepted: May 2, 2019

Article in press: May 2, 2019

Published online: May 26, 2019

Processing time: 148 Days and 14.1 Hours

Myxopapillary ependymomas are rare spinal tumours. Although histologically benign, they have a tendency for local recurrence.

We describe a patient suffering from extra- and intradural myxopapillary ependymoma with perisacral spreading. He was treated with subtotal resection and postoperative radiation therapy. After treatment, he experienced slight sphincter disorders and lumboischialgic pain with no motor or sensory disturbances. Eight months later, a tumour regression was documented. The patient is still followed-up regularly.

Lumbar myxopapillary ependymomas may present with lumbar or radicular pain, similar to more trivial lesions. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the primary modality for diagnosis. The treatment aim is to minimize both tumour and therapy-related morbidity and to involve different treatment modalities.

Core tip: Myxopapillary ependymomas are rare spinal tumours. They may present with spinal or radicular pain, similar to more trivial lesions. The treatment aim is to minimize both tumour and therapy-related morbidity. We present a patient with extra- and intradural mixopapillary ependymoma with perisacral spreading.

- Citation: Strojnik T, Bujas T, Velnar T. Invasive myxopapillary ependymoma of the lumbar spine: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2019; 7(10): 1142-1148

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v7/i10/1142.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v7.i10.1142

The spinal cord can be affected by various tumours, including ependymomas[1]. More frequently encountered intracranially, these are rare malignancies that arise from the cells lining the ventricles and the central canal of the spinal cord. The current hypothesis of tumour formation is that these lesions originate from the extrusion of ependymal cells before neural tube closure[2].

There are many histological types that differ in clinical course and mode of treatment. In the spinal cord, two locations of ependymomas have been described, namely intradural and extradural[3]. Intradurally, spinal ependymomas most commonly occur as intramedullary lesions throughout the entire spinal cord and represent 40% to 60% of spinal cord tumours in adults[2]. The intradural extra-medullary location is very rare, with the exception of tumours arising from the lumbosacral region, such as filum terminale, cauda equine and conus medullaris[2-4]. These exhibit histological features of myxopapillary ependymomas [World Health Organization (WHO) grade I][2]. Extradurally, ependymomas occur in the sacrum, presacral tissues or even in subcutaneous tissues over the sacrum. These two tumour locations lead to different management strategies. In both, gross-total resection is the treatment of choice when feasible[3]. However, there is still not a standard therapeutic principle for this disease[5]. The role of radiation therapy has not been adequately studied for either tumour location[3].

We present a patient with a slowly growing myxopapillary ependymoma located intra- and extradurally, involving the sacrum and infiltrating the lumbar and sacral nerves. Treatment of such extensive extra- and intradural myxopapillary epenymoma with perisacral spreading presented a great challenge.

A 51-year old male was admitted to the neurosurgical department on August 2014 due to a planned operation of an extensive intradural tumour with perispinal spreading.

First signs and symptoms were noticed approximately seven years before the admission, when he complained about lumboischialgic pain involving both legs. No other difficulties were reported by the patient at that time, and his neurological condition was intact.

No past illnesses were documented.

Personal and family history was unremarkable.

During the neurological examination, the patient complained of lumbar and radicular pain and occasional difficulties with micturition and defecation. There were no abnormalities in neurological function, except for slightly decreased sensory function in the right L5 and S1 dermatomes. Sphincter control was intact.

Laboratory examinations were within the normal range. Haemostasis was normal, as was the blood count and the biochemistry test. Tumour marker levels were not increased.

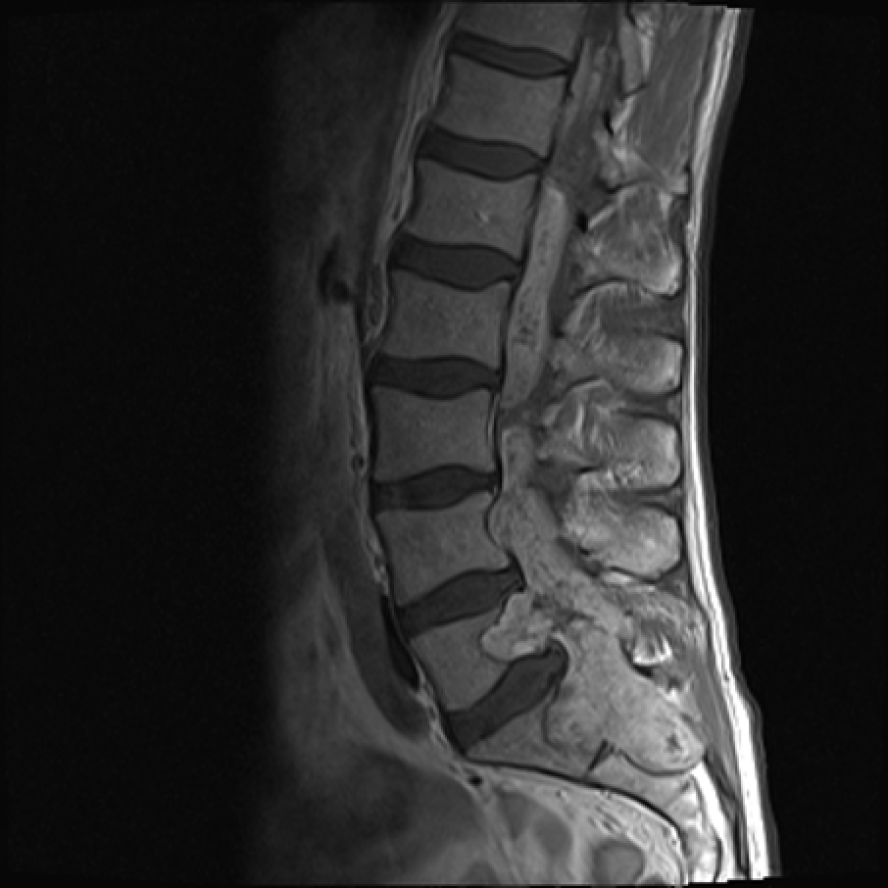

Diagnostic imaging in 2007, which included X-rays and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), revealed only slight degenerative changes in the lumbar spine, according to the neuroradiological report, although the tumour growth was already visible from the L4 to S2 level (Figure 1). The neuroradiological report did not document any signs of neoplastic lesions, and the patient was not referred to the neurosurgeon. The pain was remitting and relapsing, but no neurological symptoms were reported by the patient. In July 2014, an MRI was performed again due to constant lumbar and radicular pain. On that occasion, an extensive tumorous lesion was seen intramedullary, extending from the Th11 level and invading the conus medullaris. The tumour encompassed the entire sacral and lumbar canal to the S2 level, invading the vertebrae and spreading to perispinal muscles. Contrast homogenously enhanced the tumour (Figure 2). The radiological working diagnosis was paraganglioma or ependymoma.

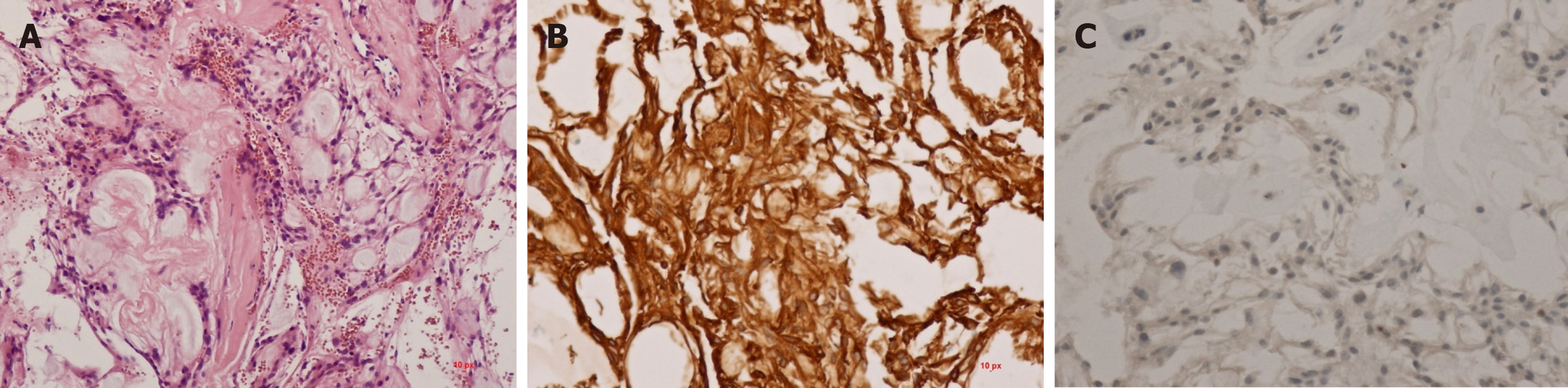

The working diagnosis was set according to the radiological characteristics, classifying the expansive lesion as a paraganglioma or ependymoma. The final diagnosis, according to the histological features, confirmed that the tumour was a myxopapillary ependymoma.

Due to the extensiveness of the lesion, surgical treatment with tumour reduction was recommended. A laminectomy on the L4 to S1 levels was performed, and a partial reduction was made under electrophysiological monitoring. The tumour tissue was brownish to purple, adherent, vividly vascularised and covering the entire dorsal aspect of the sacral bone, invading the vertebral laminae and bodies, the spinal canal extradurally and extending through the dura into the subdural space and medulla. The lower lumbar and sacral nerves were also affected, and no clear dissection was possible. Due to such extensive infiltration, a radical excision was not possible. The dura was approximated as best as possible and covered with a lyophilised dural patch, collagen sponge and fibrin glue.

The postoperative course was uneventful. No neurological deterioration was observed. According to the histological examination, the tumour was a myxopapillary ependymoma (Figure 3). After the recovery, oncological treatment with irradiation was recommended. The patient received 56 Greys in 28 fractions and was followed-up with an oncologist and neurosurgeon every 4 mo. No further growth was recognised by control MRI imaging (Figure 4). The patient experienced slight sphincter disorders and lumboischialgic pain with no motor or sensory disturbances. After 8 mo, a tumour regression was documented. The patient is still followed-up regularly.

Myxopapillary ependymoma was first reported by Kernohan in 1932 as a subtype of ependymoma[6]. These are rare spinal tumours in children and adults, although more frequent in the former. Although histologically considered benign tumours (WHO grade I) with long survival rates, they exhibit a tendency for local recurrence. Additionally, aggressive behaviour has also been described and may lead to dissemination through cerebrospinal fluid and even systemic metastases[7-9]. The intradural ependymomas, especially those in the lumbosacral region, exhibit the potential for spreading throughout the central nervous system (commonly referred to as CNS), whereas extradural tumours are more frequently associated with extraneural metastases[3].

In the lumbosacral region, the majority of ependymomas arise from the intradural filum terminale. Histologically, myxopapillary ependymomas comprise the majority of cases. At gross examination, they are often well-encapsulated, soft, vascular and lobular or sausage-shaped masses[3,10]. They may grow quite large, filling and expanding the spinal canal[11,12]. Extradural ependymomas are very rare and arise around or in the sacrum[3]. Our patient had the tumour in both locations, intra- and extradurally, due to such extensive tumour growth and spreading to the perisacral tissues.

The diagnosis of a spinal tumour requires a high level of suspicion, which is based upon the clinical signs and symptoms, as well as spine-directed MRI. Both a complete neurological examination and MRI are equally important to precisely delineate the disease[3,13]. Ependymomas may present with lumbar or radicular pain, weakness and urinary symptoms[14]. However, many patients have a long history of nonspecific complaints prior to the clinical presentation, owing to a slow growth of the myxo-papillary ependymoma. Therefore, the diagnosis is often delayed[15]. The symptoms usually consist of pain during walking, frequently located in the calves, which is rapidly relieved by stooping, sitting or otherwise adopting a flexed posture of the hips, and recurs on attempting to walk again. These symptoms may mimic lumbar disc herniation, lumbar spinal stenosis or other spinal tumours[5]. Our patient had a non-specific presentation with lumboishialgic pain in both legs, first reported seven years before surgery. Consequently, when a patient presents with long prodromal and nonspecific lower extremity symptoms, neuroradiological re-evaluation is suggested.

The clinical and radiographic findings of spinal lesions are not specific enough to identify a myxopapillary ependymoma. Differential diagnosis should take into account some other more frequent extramedullary tumours in this region, including schwannomas, meningiomas or dermoid tumours, as well as degenerative lesions. MRI is the primary modality for imaging spinal neoplasms and of vital importance in making the diagnosis. It may uncover spinal or paraspinal neoplasms, as well as unusual degenerative conditions[2]. MRI is helpful in identifying the extent of the tumour and its relationship with intraspinal structures, as well as the eventual bone destruction and invasion of the surrounding soft tissues[10]. The key point of diagnosis is the pathological result[5].

The treatment aim is to minimize both tumour and therapy-related morbidity. Usually, it encompasses different modalities[9,14]. It generally involves surgical treatment with or without adjuvant radiotherapy, which is most commonly used in patients with subtotal resection of intradural ependymomas, local recurrence or CNS dissemination. Although the effect of adjuvant radiotherapy is significant in younger patients, the data supporting the use of radiation therapy for extradural ependymomas are lacking, and there is no substantial role for chemotherapy in tumour treatment, except in children in an effort to delay radiation. The surgical methods include gross total removal, piecemeal total removal and subtotal removal. When possible, a complete resection is made, which is associated with decreased recurrence rates and improvement in performance score, especially in older patients[3,5,7,9,16]. The grossly encapsulated tumours could be removed intact. Indeed, en block rather than piecemeal resection should be performed, since the latter has been associated with higher recurrence rates[17]. However, when the lesion is large or unencapsulated or infiltrates and adheres to the nerve roots, the piecemeal total removal could be adopted[3,5]. When the conus medullaris and cauda equina are involved with the tumour, gross-total resection can be obtained in 43% to 59% of cases[17,18]. Under electrophysiological monitoring, we performed subtotal removal of the tumour in this case. There was no postoperative neurological deficit caused by piecemeal partial removal of the intra- and extradural parts. As a result of subtotal tumour resection, postoperative radiation therapy was necessary. Although there was no evidence of a dose-response relationship between the amount of radiation and tumour progression, most authorities recommend radiation doses in the range of 40 Gy to 50 Gy[19]. Our patient received 56 Gy in 28 fractions. At the follow-up, a good outcome was observed.

The prognosis of ependymomas depends on many factors, such as tumour location, histology, stage of the disease and the extent of surgical resection. This is particularly important for myxopapillary tumours that occur in the lumbar spine[7]. Despite the risk for local recurrence and CNS dissemination, the prognosis for intradural lumbosacral ependymomas is good, with a 10-year survival rate of 90%. On the other hand, the extradural location bears worse prognosis, which is better for dorsal sacral tumours than presacral tumours[3]. In our case, a partial tumour resection was achieved and postoperative radiation therapy of the spinal cord was effective. After 8 mo, tumour regression was documented by MRI. The patient had an uneventful clinical course and has been regularly followed up for over 18 mo after the surgery.

Many factors may influence the prognosis of myxopapillary ependymomas of the lumbar spine. Despite the risk of tumour recurrence and CNS dissemination, the prognosis of lumbosacral ependymomas is usually good. As the disease may present with signs and symptoms similar to more trivial lesions, a high level of clinical suspicion is necessary.

We thank Dr. Irena Strojnik for technical assistance in preparing the manuscript and Dr. Kristina Gornik Kramberger for providing microphotography of the tumour.

| 1. | Vera-Bolanos E, Aldape K, Yuan Y, Wu J, Wani K, Necesito-Reyes MJ, Colman H, Dhall G, Lieberman FS, Metellus P, Mikkelsen T, Omuro A, Partap S, Prados M, Robins HI, Soffietti R, Wu J, Gilbert MR, Armstrong TS; CERN Foundation. Clinical course and progression-free survival of adult intracranial and spinal ependymoma patients. Neuro Oncol. 2015;17:440-447. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Morselli C, Ruggeri AG, Pichierri A, Marotta N, Anzidei M, Delfini R. Intradural Extramedullary Primary Ependymoma of the Craniocervical Junction Combined with C1 Partial Agenesis: Case Report and Review of the Literature. World Neurosurg. 2015;84:2076.e1-2076.e6. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Fassett DR, Schmidt MH. Lumbosacral ependymomas: a review of the management of intradural and extradural tumors. Neurosurg Focus. 2003;15:E13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sevick RJ, Wallace CJ. MR imaging of neoplasms of the lumbar spine. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 1999;7:539-553, ix. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Al-Habib A, Al-Radi OO, Shannon P, Al-Ahmadi H, Petrenko Y, Fehlings MG. Myxopapillary ependymoma: correlation of clinical and imaging features with surgical resectability in a series with long-term follow-up. Spinal Cord. 2011;49:1073-1078. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Koeller KK, Shih RY. Intradural Extramedullary Spinal Neoplasms: Radiologic-Pathologic Correlation. Radiographics. 2019;39:468-490. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 128] [Article Influence: 21.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Moynihan TJ. Ependymal tumors. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2003;4:517-523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Plans G, Brell M, Cabiol J, Villà S, Torres A, Acebes JJ. Intracranial retrograde dissemination in filum terminale myxopapillary ependymomas. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2006;148:343-6; discussion 346. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Feldman WB, Clark AJ, Safaee M, Ames CP, Parsa AT. Tumor control after surgery for spinal myxopapillary ependymomas: distinct outcomes in adults versus children: a systematic review. J Neurosurg Spine. 2013;19:471-476. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Shors SM, Jones TA, Jhaveri MD, Huckman MS. Best cases from the AFIP: myxopapillary ependymoma of the sacrum. Radiographics. 2006;26 Suppl 1:S111-S116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Moelleken SM, Seeger LL, Eckardt JJ, Batzdorf U. Myxopapillary ependymoma with extensive sacral destruction: CT and MR findings. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1992;16:164-166. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Biagini R, Demitri S, Orsini U, Bibiloni J, Briccoli A, Bertoni F. Osteolytic extra-axial sacral myxopapillary ependymoma. Skeletal Radiol. 1999;28:584-589. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Chamberlain MC, Tredway TL. Adult primary intradural spinal cord tumors: a review. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2011;11:320-328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 159] [Cited by in RCA: 201] [Article Influence: 13.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Bandopadhayay P, Silvera VM, Ciarlini PDSC, Malkin H, Bi WL, Bergthold G, Faisal AM, Ullrich NJ, Marcus K, Scott RM, Beroukhim R, Manley PE, Chi SN, Ligon KL, Goumnerova LC, Kieran MW. Myxopapillary ependymomas in children: imaging, treatment and outcomes. J Neurooncol. 2016;126:165-174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Bagley CA, Wilson S, Kothbauer KF, Bookland MJ, Epstein F, Jallo GI. Long term outcomes following surgical resection of myxopapillary ependymomas. Neurosurg Rev. 2009;32:321-34; discussion 334. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 71] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kukreja S, Ambekar S, Sharma M, Sin AH, Nanda A. Outcome predictors in the management of spinal myxopapillary ependymoma: an integrative survival analysis. World Neurosurg. 2015;83:852-859. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Sonneland PR, Scheithauer BW, Onofrio BM. Myxopapillary ependymoma. A clinicopathologic and immunocytochemical study of 77 cases. Cancer. 1985;56:883-893. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Celli P, Cervoni L, Cantore G. Ependymoma of the filum terminale: treatment and prognostic factors in a series of 28 cases. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1993;124:99-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Andoh H, Kawaguchi Y, Seki S, Asanuma Y, Fukuoka J, Ishizawa S, Kimura T. Multi-focal Myxopapillary Ependymoma in the Lumbar and Sacral Regions Requiring Cranio-spinal Radiation Therapy: A Case Report. Asian Spine J. 2011;5:68-72. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article which was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See:

Manuscript source: Invited manuscript

Specialty type: Medicine, Research and Experimental

Country of origin: Slovenia

Peer-review report classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good):

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Coskun A, Afzal M S-Editor: Dou Y L-Editor: Filipodia E-Editor: Wu YXJ