Published online Feb 26, 2026. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v14.i6.118184

Revised: January 24, 2026

Accepted: February 5, 2026

Published online: February 26, 2026

Processing time: 49 Days and 11.5 Hours

Tuberculosis remains an important cause of uveitis in tuberculosis-endemic re

We report a case of a middle-aged female, a known case of celiac disease and rec

This case highlights the need for a high index of suspicion for ocular tuberculosis in patients presenting with po

Core Tip: This case underscores the diagnostic challenges posed by posterior uveitis in patients with underlying autoimmune conditions such as celiac disease and recurrent anemia, especially in tuberculosis-endemic regions. The presence of erythema nodosum and systemic symptoms can mimic other granulomatous diseases like sarcoidosis, making timely and accurate diagnosis difficult. However, a comprehensive evaluation including immunological testing, history of tuberculosis, family history, and response to antitubercular therapy was pivotal in establishing presumed tubercular chorioretinitis as the diagnosis. The case highlights the importance of maintaining a high index of suspicion for ocular tuberculosis and the need for a multidisciplinary approach to management, utilizing antitubercular drugs, corticosteroids, and immunosuppressants when necessary, to achieve optimal clinical outcomes.

- Citation: Singh N, Morya AK, Walia S, Udenia H. Tubercular chorioretinitis mimicking sarcoidosis in a patient with celiac disease and erythema nodosum: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2026; 14(6): 118184

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v14/i6/118184.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v14.i6.118184

Tuberculosis remains a prevalent cause of uveitis in endemic regions and is often described as a “great masquerader” because of the absence of pathognomonic clinical features and its ability to mimic other granulomatous inflammatory disorders[1]. Its ocular manifestations frequently overlap with those of sarcoidosis, particularly in the presence of systemic features such as erythema nodosum, leading to significant diagnostic challenges[1,2]. This overlap is especially problematic in tuberculosis-endemic populations, where a diagnosis of sarcoidosis is often made in patients who present with erythema nodosum.

Diagnostic complexity is further increased in patients with chronic autoimmune diseases like celiac disease, which seldom but does have a documented association with recurrent uveitis. The nonspecific autoimmune serological markers include positivity for antinuclear antibody (ANA) and thus can lead to diagnostic confusion with systemic inflammatory disorders such as systemic lupus erythematosus. Therefore, the need for careful clinical correlation and the judicious use of ancillary investigations becomes indispensable for establishing the correct etiology and guiding appropriate mana

A 34-year-old woman presented in 2025 with episodic, recurrent episodes of bilateral blurred vision, ocular pain, photophobia, and floaters for 1.5 years.

She has had these ocular complaints for the last 1.5 years. With biopsy-proven celiac disease diagnosed in the year 2021 and chronic anemia requiring multiple packed red blood cell transfusions.

She also had a history of a completed six-month course of antitubercular therapy for cervical lymph node tuberculosis in 2022.

There was a family history of pulmonary tuberculosis in her brother. During recent ocular exacerbations, she reported generalized fatigue and reduced appetite.

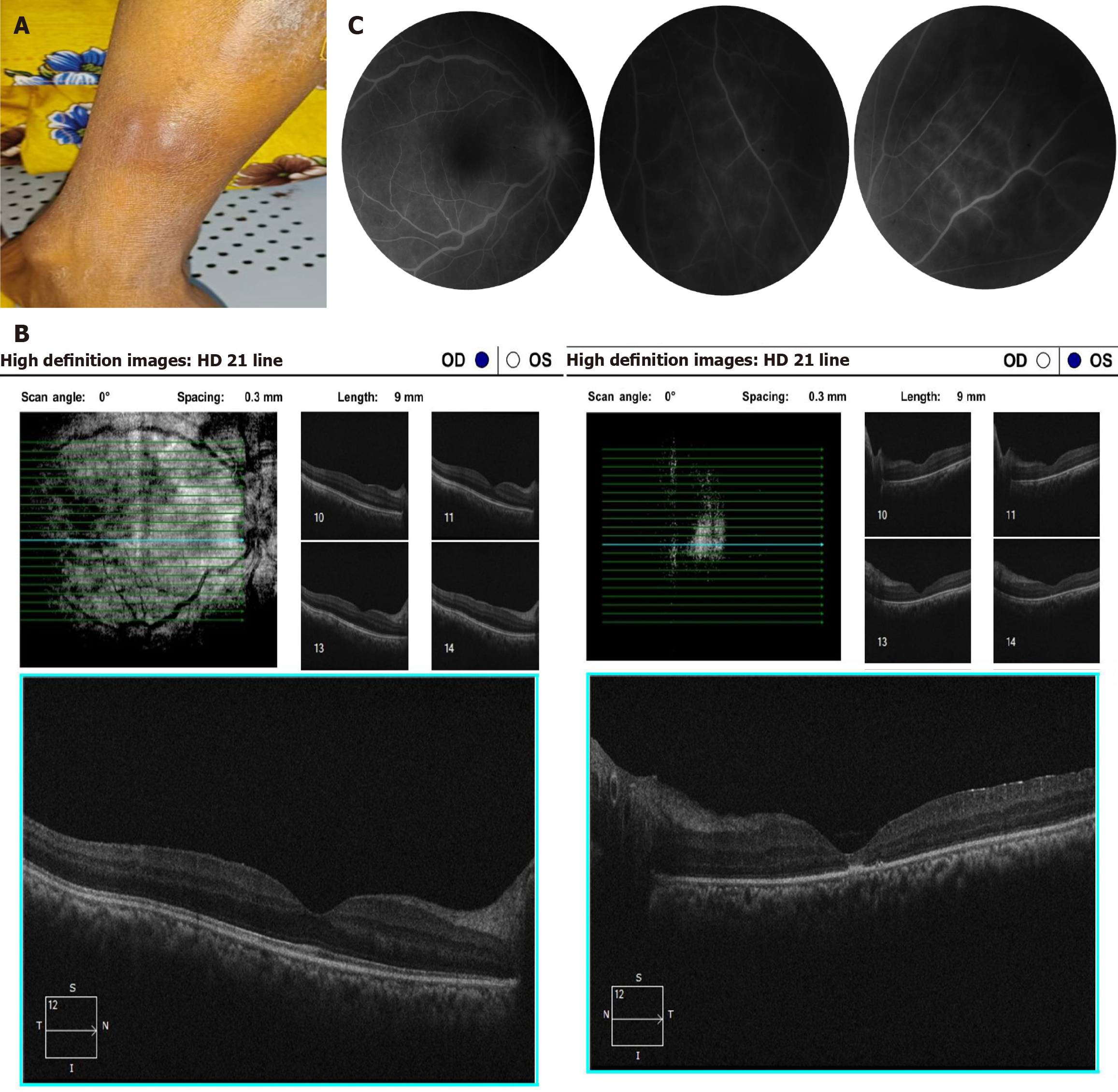

Systemic examination revealed a 3-cm tender, erythematous-to-violaceous subcutaneous nodule over the left shin, clinically consistent with erythema nodosum.

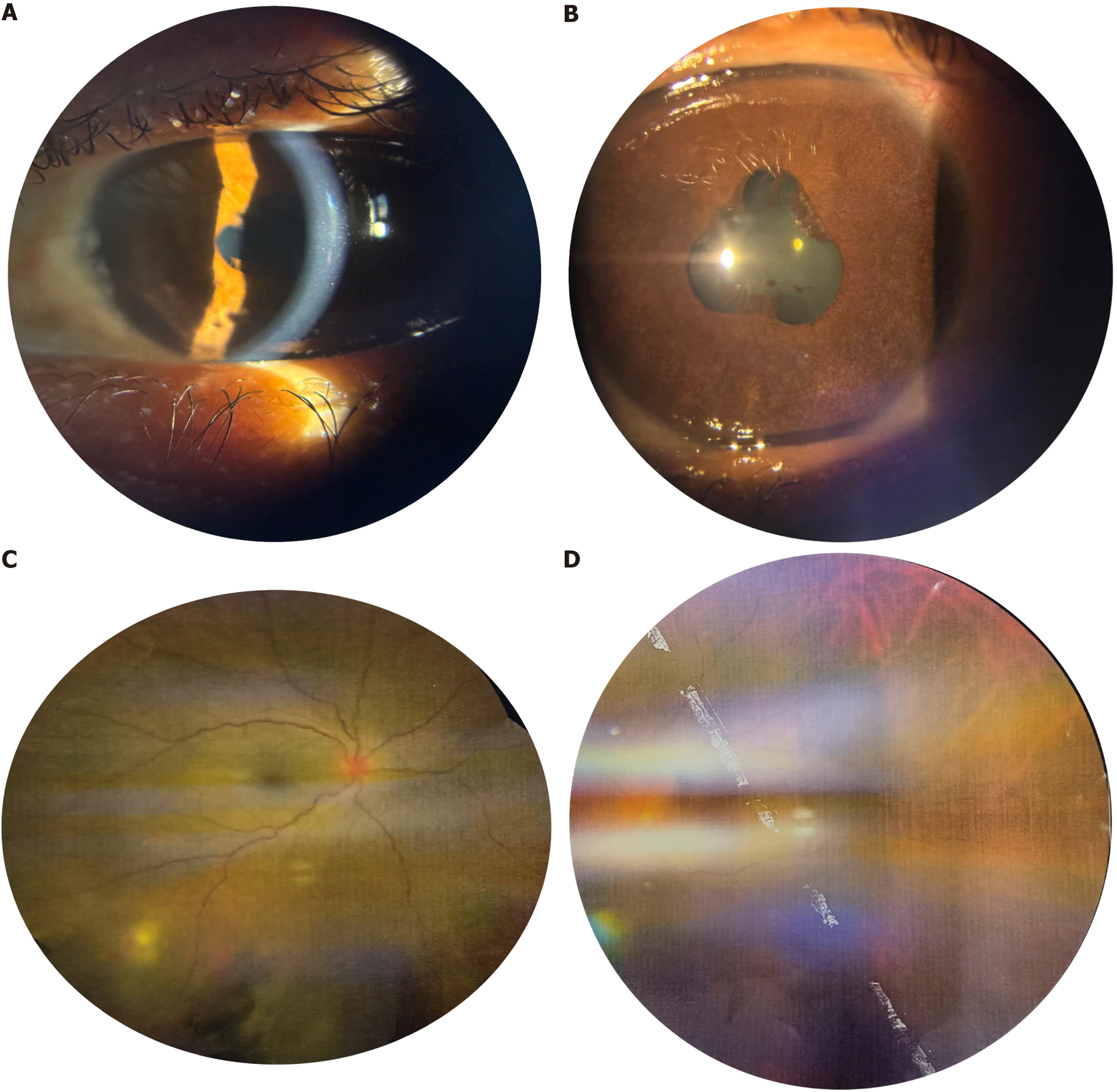

In the right eye, best-corrected visual acuity was 6/9, the anterior chamber was quiet, and fundus examination showed grade I vitritis with two to three hypopigmented healed chorioretinal patches in the inferotemporal quadrant of the posterior pole. In the left eye, best-corrected visual acuity was 6/24. There was diffuse iris atrophy with a festooned pupil secondary to broad-based posterior synechiae at the 2 o’clock, 6 o’clock, and 11 o’clock positions, as well as a complicated cataract with polychromatic luster. Fundus details in the left eye were obscured by grade III vitritis and a non-dilating pupil, although the optic disc appeared hyperemic (Figure 1).

Laboratory evaluation revealed a positive interferon-gamma release assay, pancytopenia, a negative ANA profile, and the absence of anti-dsDNA antibodies, and normal complement levels suggested that these findings were secondary to chronic inflammation rather than systemic lupus erythematosus.

Fundus fluorescein angiography (FFA) of the right eye revealed segmental perivascular leakage in a few areas, indicating active vasculitis in the mid-peripheral retina without any signs of leakage in the macular area or capillary dropout areas. FFA photos of the left eye could not be obtained. The high-resolution computed tomography scan of the chest showed multiple subcentimetric paratracheal and subcarinal nodes with calcification (Figure 2).

The clinical differential diagnoses were sarcoidosis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and ocular tuberculosis. Blood tests for angiotensin-converting enzyme and calcium levels were reported to be within the normal range. Also, the lack of hilar adenopathy did not support the presence of sarcoidosis.

A positive interferon-gamma release assay, along with supportive clinical history and therapeutic response, favored a diagnosis of tubercular chorioretinitis.

The patient was re-initiated on a four-drug antitubercular regimen consisting of rifampicin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide, and ethambutol, along with systemic corticosteroids. Posterior sub tenon triamcinolone injections were administered, first in the left eye followed by the right. At the 2-week follow-up, the patient reported improvement in symptoms, and visual acuity in the right eye improved to 6/6 and the left eye to 6/9. However, after 2 weeks of completion of systemic steroid therapy, there was again a recurrence of vitritis and hence systemic azathioprine was started as a steroid-sparing immu

The patient’s signs and symptoms improved after initiating the treatment, and she’s been under constant follow-up for the last 1 year with no recurrence.

This case highlights just how closely sarcoidosis and tuberculosis can mimic each other, particularly in regions where tuberculosis is common. Symptoms such as erythema nodosum can sometimes lead doctors to initially suspect sarcoidosis[1]. According to Agrawal et al[1] in areas with a high prevalence of tuberculosis, it can be difficult to tell the two apart, because even though they sit at different points on a disease spectrum, they share many similar clinical, radiological, and immunological characteristics[1]. Erythema nodosum is not specific to any single disease and has been observed in a wide range of inflammatory and infectious conditions, including tuberculosis, even though it is tradi

In regions where tuberculosis is endemic, the markers usually relied upon to support a diagnosis of sarcoidosis may not always be reliable. Sarcoidosis becomes less likely when there is no enlargement of the lymph nodes near the lungs and when calcium levels and serum angiotensin-converting enzyme are normal[3]. A multicentered study conducted in a high tuberculosis-burden setting showed that depending solely on these markers can be misleading and highlighted the importance of excluding tuberculosis before confirming a diagnosis of ocular sarcoidosis[3]. In this case, there were no systemic or imaging findings to support sarcoidosis. Other differential diagnosis of posterior uveitis were also systematically considered. Behçet disease was unlikely due to the absence of recurrent oral or genital ulcers and lack of occlusive retinal vasculitis. Infectious uveitis, including toxoplasmosis and viral etiologies, was excluded based on lesion mor

The situation can be further complicated when autoimmune conditions, such as celiac disease, are also present. Individuals with autoimmune disorders may show nonspecific blood markers, like positive antinuclear antibodies, and uveitis has been reported as an extraintestinal manifestation of celiac disease[4]. In the absence of other clinical or immunological signs, isolated ANA positivity is common in the general population and does not indicate systemic lupus erythematosus[5]. International guidelines emphasize that ANA results should always be interpreted with care and in the context of the patient’s overall clinical picture to avoid overdiagnosis[5]. In this patient, celiac disease was therefore considered as a potential contributor to immune dysregulation rather than a primary etiological factor for posterior uvei

The diagnosis in this case was classified as presumed ocular tuberculosis, because of the diagnostic limitations associated with ocular involvement. Microbiological confirmation is usually negative due to the paucibacillary nature of intraocular disease. Tuberculous uveitis is primarily diagnosed based on characteristic eye findings. Both healed and active choroidal lesions appear as pigmented, atrophic patches along the retinal vessels, which are well-established indicators of ocular tuberculosis[6]. In patients with posterior uveitis or chorioretinitis, evidence of prior tuberculosis exposure, such as a positive interferon-gamma release assay, adds strong support to the diagnosis[7].

Current guidelines for diagnosing ocular tuberculosis stress the importance of combining clinical signs, immunological tests, and imaging findings, even if the lungs appear normal[8]. Ocular tuberculosis can be difficult to manage because relapses may happen despite following normal anti-tuberculosis medication. Studies indicate that the generally pre

This case underscores the intricate diagnostic challenges encountered when distinguishing between sarcoidosis and tuberculosis, particularly in regions with a high prevalence of tuberculosis. Overlapping clinical features, such as erythema nodosum and similar radiological and immunological findings, often complicate the clinical picture and may lead to diagnostic uncertainty. The coexistence of autoimmune conditions like celiac disease adds an additional layer of complexity, as nonspecific serological markers such as ANA can be misleading and should not be interpreted in isolation. It is therefore essential to adopt a comprehensive diagnostic approach, integrating clinical, radiological, and laboratory findings, while maintaining a high index of suspicion for tuberculosis in endemic areas. Furthermore, the management of ocular tuberculosis requires careful consideration, as relapses are possible and may necessitate prolonged and individualized therapy. Ultimately, multidisciplinary collaboration and vigilant follow-up are crucial for accurate diagnosis and optimal patient outcomes in such complex cases.

| 1. | Agrawal R, Kee AR, Ang L, Tun Hang Y, Gupta V, Kon OM, Mitchell D, Zierhut M, Pavesio C. Tuberculosis or sarcoidosis: Opposite ends of the same disease spectrum? Tuberculosis (Edinb). 2016;98:21-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Orchard TR, Chua CN, Ahmad T, Cheng H, Welsh KI, Jewell DP. Uveitis and erythema nodosum in inflammatory bowel disease: clinical features and the role of HLA genes. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:714-718. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Babu K, Biswas J, Agarwal M, Mahendradas P, Bansal R, Rathinam SR, Basu S, Ganesh SK, Konana VK, Vedhanayaki R, Philips M, Choudhary T. Diagnostic Markers in Ocular Sarcoidosis in A High TB Endemic Population - A Multicentre Study. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2022;30:163-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Saleem J, Haroon A, Hashmani N, Hashmani S. Ocular Insights: Exploring Uveitis as a Manifestation of Celiac Disease. Cureus. 2025;17:e86736. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Agmon-Levin N, Damoiseaux J, Kallenberg C, Sack U, Witte T, Herold M, Bossuyt X, Musset L, Cervera R, Plaza-Lopez A, Dias C, Sousa MJ, Radice A, Eriksson C, Hultgren O, Viander M, Khamashta M, Regenass S, Andrade LE, Wiik A, Tincani A, Rönnelid J, Bloch DB, Fritzler MJ, Chan EK, Garcia-De La Torre I, Konstantinov KN, Lahita R, Wilson M, Vainio O, Fabien N, Sinico RA, Meroni P, Shoenfeld Y. International recommendations for the assessment of autoantibodies to cellular antigens referred to as anti-nuclear antibodies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2014;73:17-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 465] [Cited by in RCA: 427] [Article Influence: 35.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Gupta A, Bansal R, Gupta V, Sharma A, Bambery P. Ocular signs predictive of tubercular uveitis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2010;149:562-570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 164] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Sudharshan S, Ganesh SK, Balu G, Mahalakshmi B, Therese LK, Madhavan HN, Biswas J. Utility of QuantiFERON®-TB Gold test in diagnosis and management of suspected tubercular uveitis in India. Int Ophthalmol. 2012;32:217-223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ang M, Vasconcelos-Santos DV, Sharma K, Accorinti M, Sharma A, Gupta A, Rao NA, Chee SP. Diagnosis of Ocular Tuberculosis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2018;26:208-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Agrawal R, Gupta B, Gonzalez-Lopez JJ, Rahman F, Phatak S, Triantafyllopoulou I, Addison PK, Westcott M, Pavesio CE. The role of anti-tubercular therapy in patients with presumed ocular tuberculosis. Ocul Immunol Inflamm. 2015;23:40-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 70] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Putera I, Ten Berge JCEM, Thiadens AAHJ, Dik WA, Agrawal R, van Hagen PM, La Distia Nora R, Rombach SM. Relapse in ocular tuberculosis: relapse rate, risk factors and clinical management in a non-endemic country. Br J Ophthalmol. 2024;108:1642-1651. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/