Published online Feb 26, 2026. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v14.i6.117655

Revised: January 20, 2026

Accepted: February 4, 2026

Published online: February 26, 2026

Processing time: 62 Days and 9.2 Hours

Appendiceal mucocele with pseudomyxoma peritonei (PMP) is a rare entity that often presents late and requires specialized management. Cytoreductive surgery (CRS) combined with hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) has become the standard of care, yet real-world surgical experiences from diverse institutions remain limited. This case series highlights five patients presenting with appendiceal mucoceles complicated by PMP, emphasizing diagnostic cha

We report five patients (aged 45-75 years) who presented with symptoms ranging from abdominal distension and umbilical nodules to incidental imaging findings. All patients underwent a comprehensive diagnostic evaluation, including labo

CRS with HIPEC remains the most effective strategy for managing appendiceal mucocele-associated PMP.

Core Tip: Appendiceal mucoceles complicated by pseudomyxoma peritonei are uncommon and often present with non

- Citation: Aby Hadeer R, Ghattas S, Farhat H, Maalouf H, Bitar JE, Ayash D, Mohtar F, Elias B, Wakim R. Cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy for appendiceal mucocele tumors: Five case reports and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2026; 14(6): 117655

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v14/i6/117655.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v14.i6.117655

Pseudomyxoma peritonei (PMP) is a rare, borderline-malignant clinical entity that includes a spectrum of lesions classically presenting as “jelly-belly”, characterized by gelatinous ascites with mucinous peritoneal implants. The term is used to describe any peritoneal dissemination of a mucus-secreting neoplasm, most commonly originating from the appendix, but also from the colon, rectum, pancreas, stomach, lung, gallbladder, fallopian tubes, breast, and ovaries[1]. As for the precise incidence of PMP, it is not well established. Historical autopsy studies approximated appendiceal mucocele incidence of 0.2%[2]. Recent reports from high-volume centers indicated the actual incidence to reach as high as 3-4 per million per year[3,4]. We herein report 5 cases of perforated appendiceal mucocele complicated by PMP.

Case 1: A 57-year-old male patient with a negative past medical history was admitted to a peripheral hospital to undergo an umbilical hernia repair. Upon incising the skin, gelatinous secretions were released from the abdomen, leading to the abortion of the surgery.

Case 2: A 52-year-old female patient with a negative past medical and surgical history presented with the chief complaint of a new onset umbilical nodule.

Case 3: A 45-year-old male patient with no previous medical or surgical history presented with a two-month history of fatigue, a 5 kg weight loss, and colicky abdominal pain.

Case 4: A 53-year-old male patient with a history of hypertension and ulcerative colitis presented to the emergency department with severe right lower quadrant abdominal pain associated with vomiting and anorexia.

Case 5: A 75-year-old previously healthy male sustained a fall, after which abdominal imaging was performed inci

Case 1: During the aborted hernia repair, a drain was placed, and biopsies were taken. The pathology result showed the presence of metastatic mucinous adenocarcinoma, most probably of colonic origin. The patient then presented to our care to treat peritoneal cavity disease. On arrival, he reported abdominal distension but no mention of pain or other acute symptoms.

Case 2: She reported noticing a recently developed, firm nodule at the umbilicus. Physical examination showed a soft, non-tender abdomen with a solid, non-reducible umbilical nodule. The patient underwent resection of this umbilical nodule, and the final pathology result was significant for a colloid mucous adenocarcinoma. She was referred for further evaluation and staging.

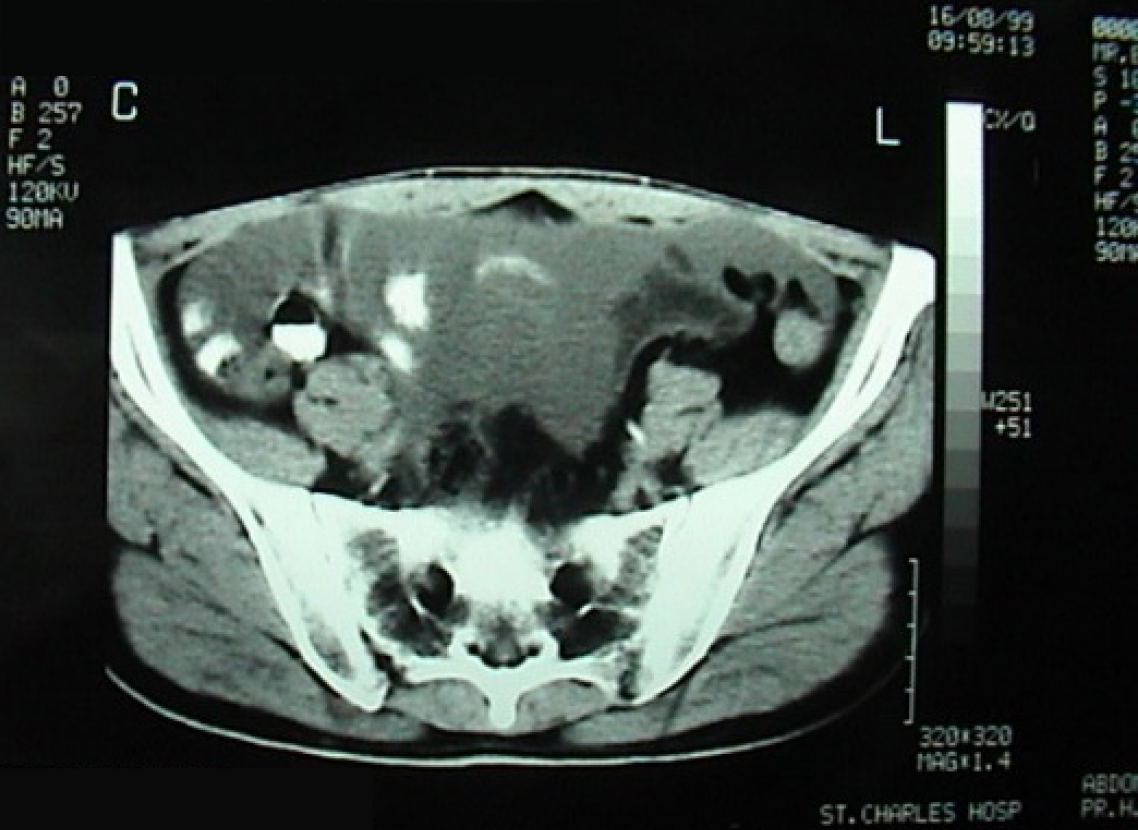

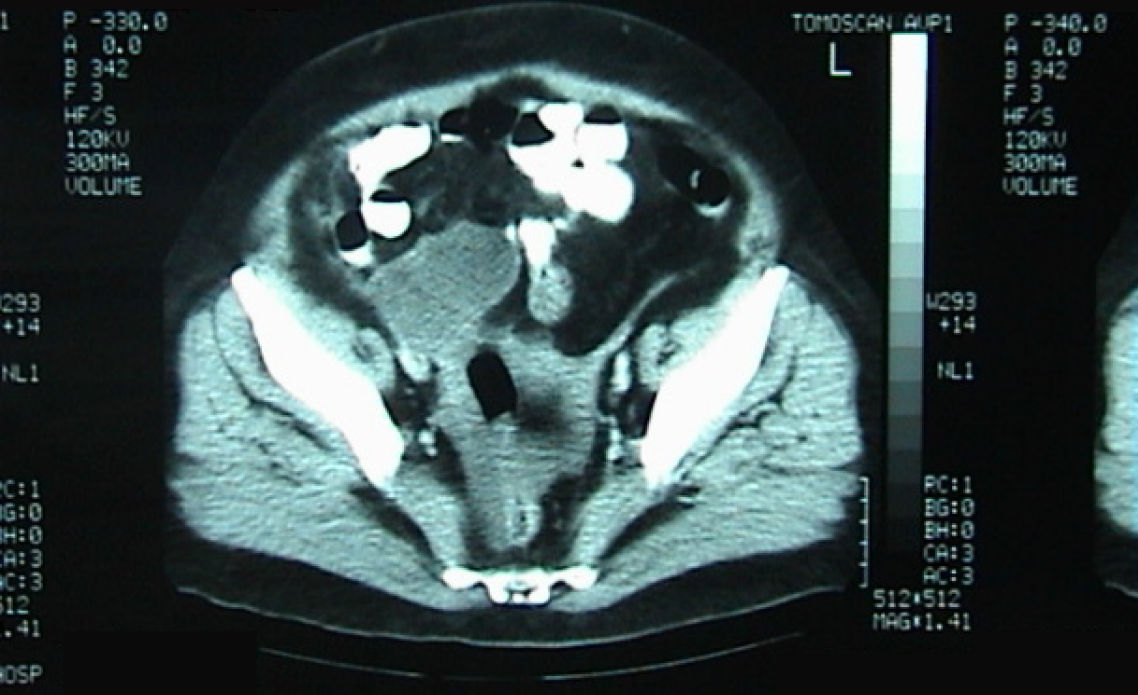

Case 3: The patient reported progressive abdominal distension associated with fatigue and weight loss. Physical examination revealed a distended, non-tender abdomen with dullness on percussion. Abdominal ultrasound showed a large amount of abdominal and pelvic ascites and nodular thickening of the anterior abdominal wall. Transabdominal percussion of this ascites revealed gelatinous content. An enhanced computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated the presence of a large amount of ascites (Figure 1).

Case 4: The patient reported an acute onset of right lower quadrant pain accompanied by vomiting and loss of appetite. No other symptoms were noted. Laboratory tests showed elevated inflammatory markers without other abnormalities. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated segmental dilation of the appendix measuring up to 33 mm, containing fluid with low signal intensity on T1 and high signal intensity on T2, with minimal infiltration of the peri-appendiceal fat. The liver and gallbladder appeared normal, and no intraperitoneal free fluid or pelvic adenopathy were identified.

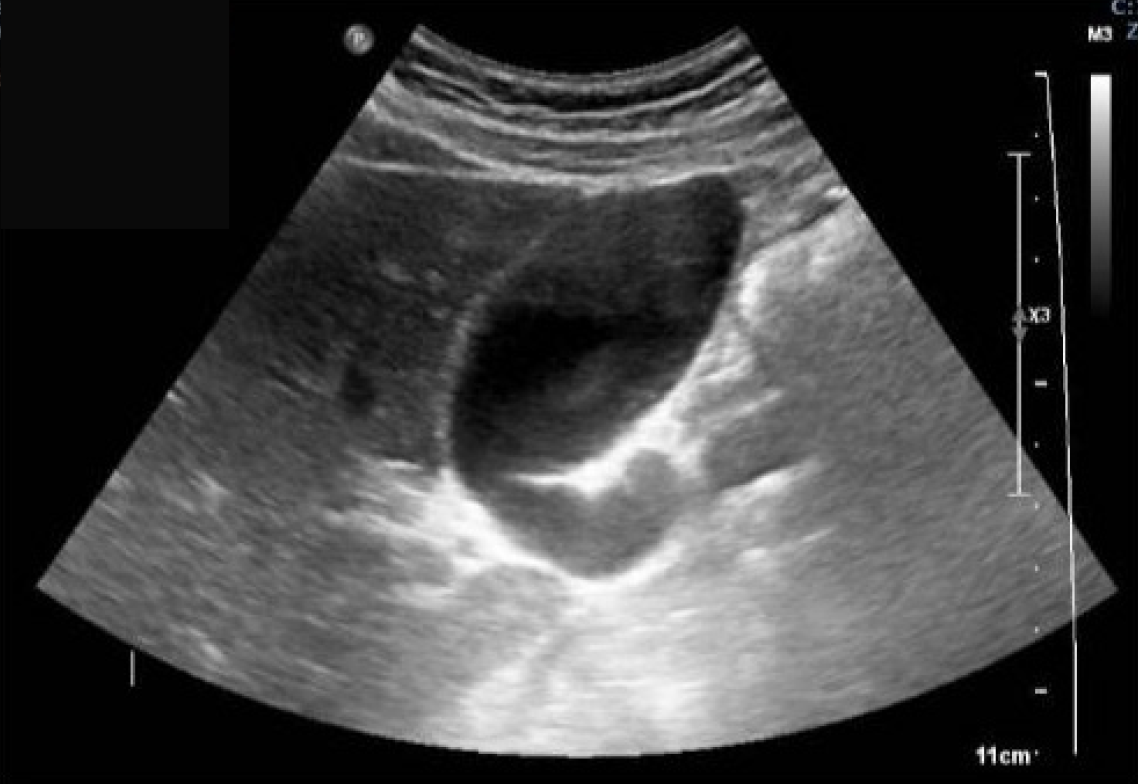

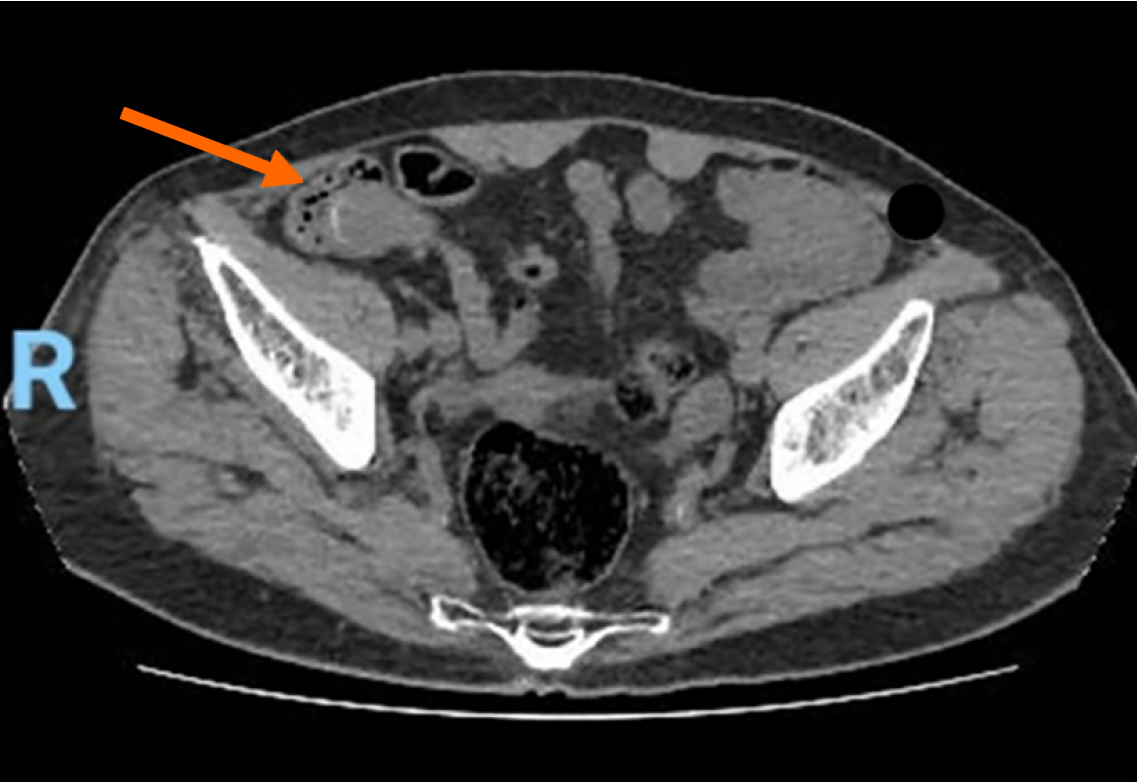

Case 5: Following the fall, an abdominal ultrasound was performed and showed a fluid-filled structure in the right iliac fossa that did not exhibit typical features of bowel loops, measuring 6.1 cm × 2.7 cm (Figure 2). A subsequent abdomen and pelvis CT scan showed a well-circumscribed, low fluid-attenuation tubular structure in continuation with the base of the cecum, grossly measuring 64 mm × 29 mm × 28 mm, corresponding to the appendix. The lesion demonstrated multifocal curvilinear mural calcifications with no mural nodularity, relevant wall interruption, or irregular wall thickening. A faint “dirty” appearance of the omentum was seen predominantly in the right mid-abdomen. Trace free fluid was noted in the left subdiaphragmatic perisplenic space, right paracolic gutter, and pelvis (Figure 3).

Case 1: He had a negative past medical history with no known chronic illnesses or previous surgeries.

Case 2: Her past medical and surgical history was unremarkable, with no known chronic illnesses or prior operations.

Case 3: He had no known medical conditions and no previous surgeries.

Case 4: His past medical history was significant for hypertension and ulcerative colitis. No other chronic illnesses or previous surgeries were reported.

Case 5: The patient had no significant past medical or surgical history prior to this presentation.

Case 1: There was no significant family history of malignancy or gastrointestinal disease. No personal history of smoking, alcohol use, or other relevant exposures was recorded.

Case 2: No relevant family history of gastrointestinal, gynecologic, or other malignancies was reported. No personal history of smoking, alcohol consumption, or other risk factors was documented.

Case 3: There was no significant family history of gastrointestinal or other malignancies. Social history was unremarkable for smoking, alcohol, or drug use.

Case 4: No significant family history of gastrointestinal or malignant disease was documented. There were no relevant lifestyle or exposure factors identified.

Case 5: There was no relevant personal or family history of malignancy, gastrointestinal disease, or other contributing conditions.

Case 1: Clinical examination revealed a soft, distended, non-tender abdomen with dullness on percussion. An abdominal drain placed during the previous operation was still in place and contained ascitic fluid. Cultures taken from this drain before removal showed the presence of Pseudomonas aeruginosa, for which targeted antibiotherapy was started.

Case 2: On examination at presentation for definitive care, the abdomen remained soft and non-tender, with no palpable masses aside from the previously resected umbilical nodule site. There were no signs of ascites or organomegaly.

Case 3: On presentation, the abdomen was distended but non-tender with diffuse dullness on percussion. No palpable masses, peritoneal signs, or hernias were noted.

Case 4: Physical examination findings at the time of presentation included localized right lower quadrant abdominal tenderness. No guarding, rebound, or other signs of peritoneal irritation were described.

Case 5: On examination, the abdomen was soft, non-distended, and non-tender, with normal bowel sounds. No palpable masses or signs of peritonitis were noted.

Case 1: Routine laboratory studies were within normal range. Serum carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) was 53.9 ng/mL (0-4), cancer antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9) was 51.13 ng/mL (0-37), and C-reactive protein was 64 (0-5).

Case 2: Laboratory findings were not detailed in the available documentation and were not reported to reveal ab

Case 3: Routine laboratory studies were within normal range. Serum tumor markers showed a CEA level of 30.2 ng/mL (0-4) and a CA 19-9 level of 3 ng/mL (0-37).

Case 4: Laboratory studies initially showed elevated inflammatory markers. One month later, routine laboratory tests were within normal range except for a partial thromboplastin time of 55.6. Further hematologic workup demonstrated the presence of lupus anticoagulants, with negative anti-DNA, antinuclea antibodies, and anticardiolipin immunoglobulin G.

Case 5: Routine laboratory tests were within normal limits.

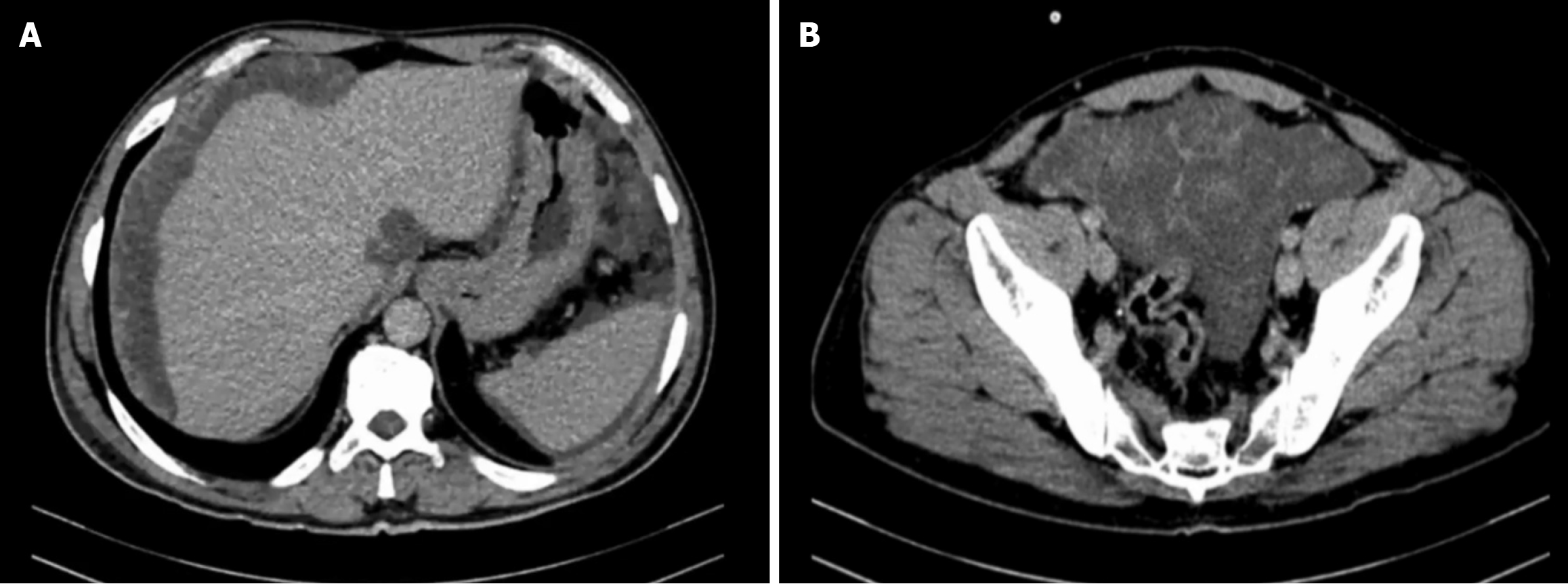

Case 1: Contrast-enhanced CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis demonstrated diffuse mucinous ascites with multiple loculated, low-attenuation peritoneal collections distributed throughout the peritoneal cavity. These collections involved the greater omentum, mesentery, paracolic gutters, subphrenic spaces, and pelvic cavity, with associated dense omental caking (Figure 4). Scalloping of the hepatic surface was clearly observed, predominantly along the right hepatic lobe, consistent with extrinsic compression by mucinous implants. No pulmonary nodules or thoracic metastases were id

CT-guided biopsy of a peritoneal lesion confirmed a mucinous tumor consistent with low-grade PMP (World Health Organization grade 1). MRI of the abdomen showed diffuse involvement of both the greater and lesser peritoneal sacs by a T2-hyperintense and T1-intermediate signal process, compatible with complex mucinous fluid. Minimal peripheral and septal enhancement was noted following contrast administration. The bowel loops appeared grossly unremarkable, without evidence of obstruction. Positron emission tomography (PET) demonstrated large-volume abdominopelvic ascites with mild F-18 fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) uptake, along with FDG-avid nodular thickening of the anterior abdominal wall, suggestive of peritoneal carcinomatosis. Mild FDG uptake was also observed at the level of the gastric antrum, inseparable from the adjacent pancreatic parenchyma. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy revealed moderate to severe pangastritis with biliary reflux, while colonoscopy showed no intraluminal masses or mucosal abnormalities.

Case 2: Contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated a well-defined soft-tissue mass in the right iliac fossa, corresponding anatomically to the appendiceal region. The lesion was contiguous with the cecum and showed features suggestive of an appendiceal mucocele with localized peritoneal involvement (Figure 5). No diffuse peritoneal implants, ascites, or omental caking were identified. Pelvic ultrasound examination was unremarkable, with no adnexal masses or free fluid. PET imaging did not demonstrate any areas of abnormal FDG uptake, suggesting the absence of metabolically active distant disease.

Case 3: Abdominal ultrasound revealed large-volume ascites occupying both the abdominal and pelvic cavities, associated with nodular thickening of the anterior abdominal wall. Percussion of the ascitic fluid suggested a gelatinous consistency. Contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen and pelvis confirmed the presence of extensive abdominopelvic ascites, without a clearly identifiable solid intra-abdominal mass. The ascitic collections were diffusely distributed, consistent with mucinous peritoneal disease. At recurrence four years later, repeat CT imaging again demonstrated large-volume mucinous ascites with diffuse peritoneal involvement, similar in distribution to the initial presentation (Figure 1). Subsequent CT examinations performed during later recurrences showed progressive accumulation of mucinous material, eventually associated with extrinsic compression of the stomach, as well as the development of a left-sided colonic mass, later confirmed to be adenocarcinoma on biopsy.

Case 4: MRI of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated segmental dilatation of the appendix measuring up to 33 mm in maximal diameter, filled with fluid exhibiting low signal intensity on T1-weighted images and high signal intensity on T2-weighted images. Minimal peri-appendiceal fat infiltration was noted, without evidence of free intraperitoneal fluid or pelvic lymphadenopathy. The liver and gallbladder appeared normal. A contrast-enhanced CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis performed three weeks after appendectomy revealed a cystic mesenteric nodule measuring 3.8 cm × 3.5 cm in the right iliac fossa, as well as segmental wall thickening of the left colon, predominantly involving the sigmoid and rectum. No diffuse peritoneal implants or ascites were identified at that time.

Case 5: Abdominal ultrasound revealed a fluid-filled tubular structure in the right iliac fossa, measuring approximately 6.1 cm × 2.7 cm, without characteristics of normal bowel loops. Subsequent contrast-enhanced CT of the abdomen and pelvis demonstrated a well-circumscribed, low-attenuation tubular structure measuring 64 mm × 29 mm × 28 mm, in continuity with the base of the cecum, consistent with an appendiceal mucocele. The lesion exhibited multifocal cur

Low-grade peritoneal mucinous neoplasia grade 1 arising from an appendiceal primary, consistent with PMP.

The final diagnosis was peritoneal pseudomyxoma arising from an appendicular mucocele with parietal rupture.

The final diagnosis was PMP from a ruptured appendiceal mucocele.

The final diagnosis was residual PMP following appendiceal mucocele perforation.

The final diagnosis was appendiceal pseudomyxoma.

The patient was scheduled for complete cytoreductive surgery (CRS) and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC). Entry into the abdomen was accomplished through a midline xypho-pubic incision with excision of the umbilicus. Upon entry, large quantities of gelatinous mucinous secretions were released. Careful inspection and assessment of the abdomen were performed to evaluate the peritoneal cancer index (PCI), which returned at 25/39. Multiple mucinous nodules around the abdomen, along with thick omental caking, were identified. Small lesions less than 2 mm were seen in the mesentery and another in the Douglas pouch. A large diaphragmatic peritoneal lesion was noted, as well as a large lesion in the hepatic pedicle invading the retro-portal space and the hiatus of Winslow. Multiple nodules were also identified in the gastrohepatic omentum and the gastrosplenic omentum.

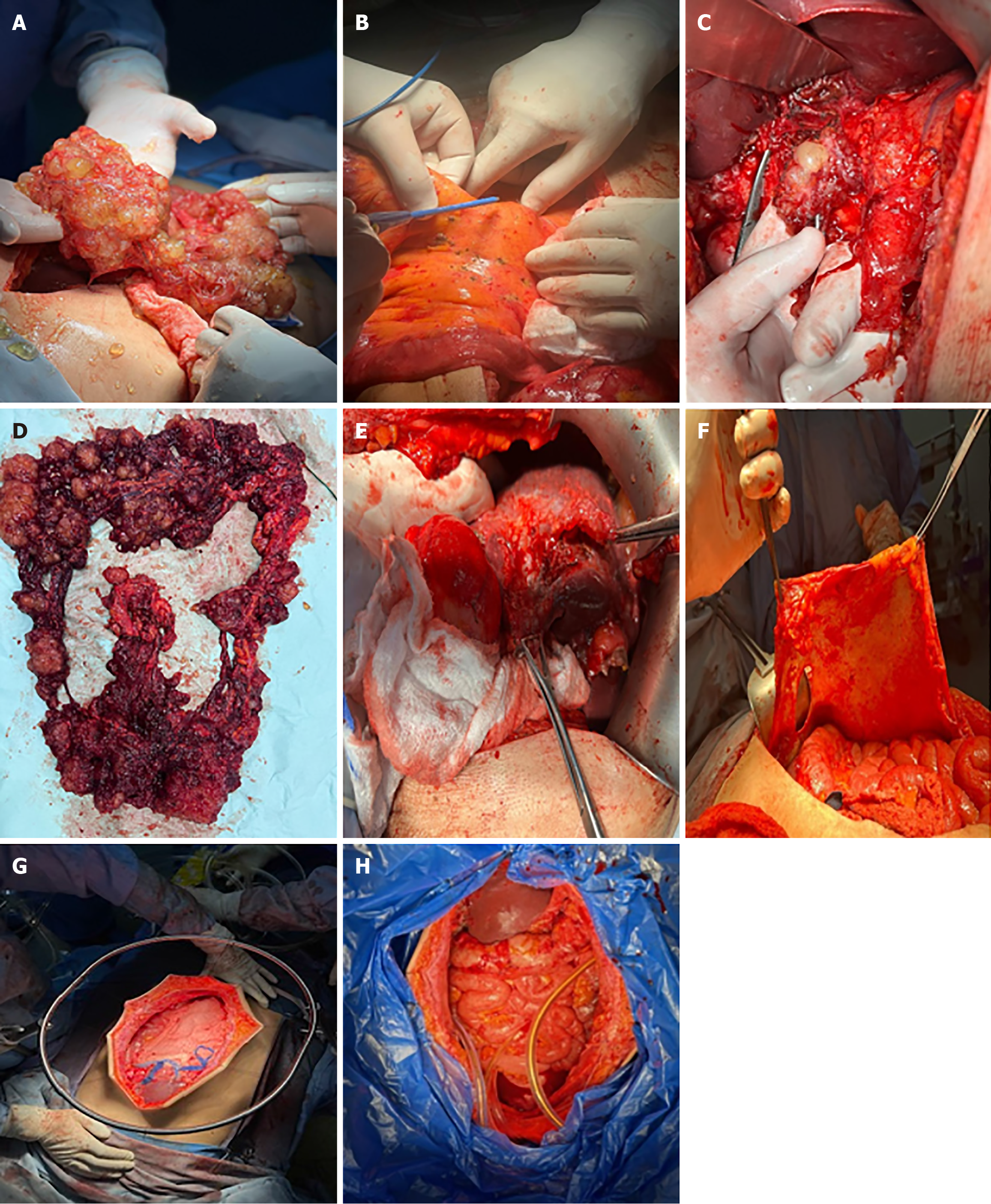

Complete peritonectomy was performed starting on the subdiaphragm right and left bilaterally, reaching the Douglas pouch, with complete omentectomy, excision of the hepatic capsule and the hepatic pedicle lesion, and cholecystectomy. Omental bursectomy, including the pancreatic capsule and the serosal surface of the adjacent antrum, was performed. HIPEC was then carried out using the coliseum technique with suspension of the abdominal walls for 90 minutes using mitomycin 10 mg/m2 in 3 L of 1.5% dextrose peritoneal solution at 41 degrees. The abdomen was washed with 3 L of water, and finally, an appendectomy was performed. Total operating time was 8 hours. (Figure 6).

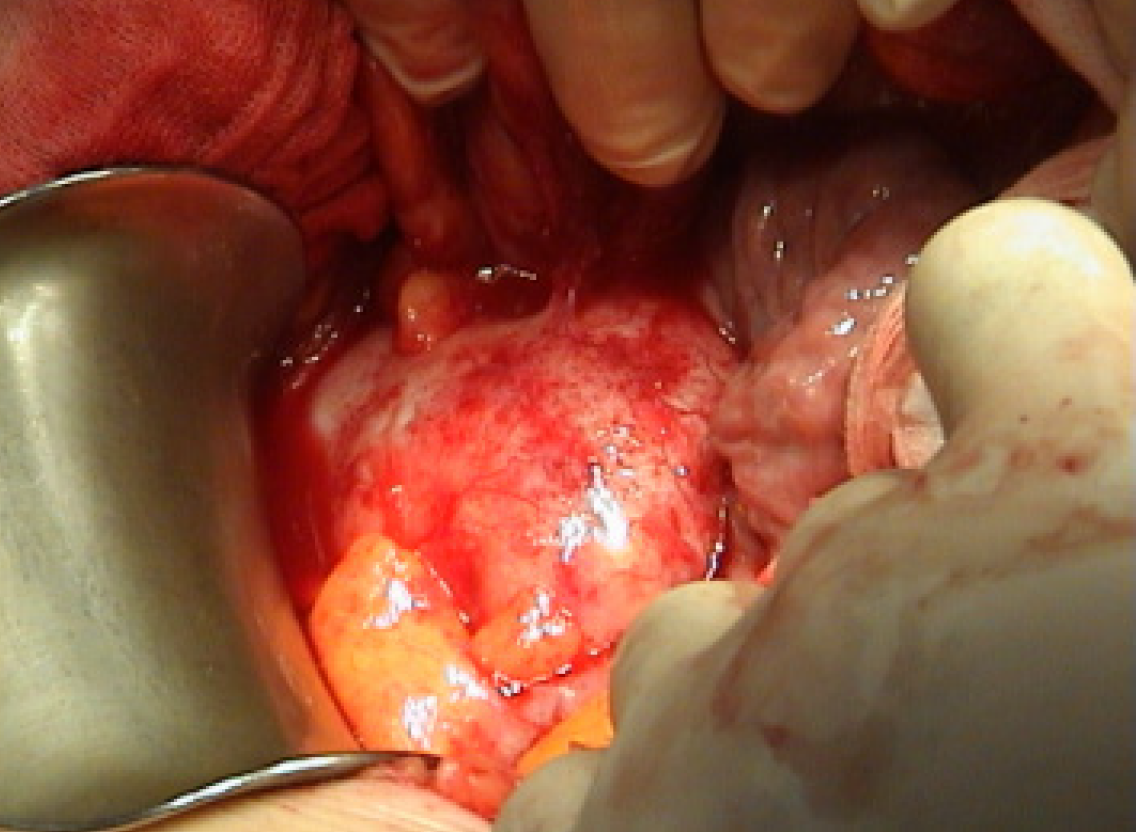

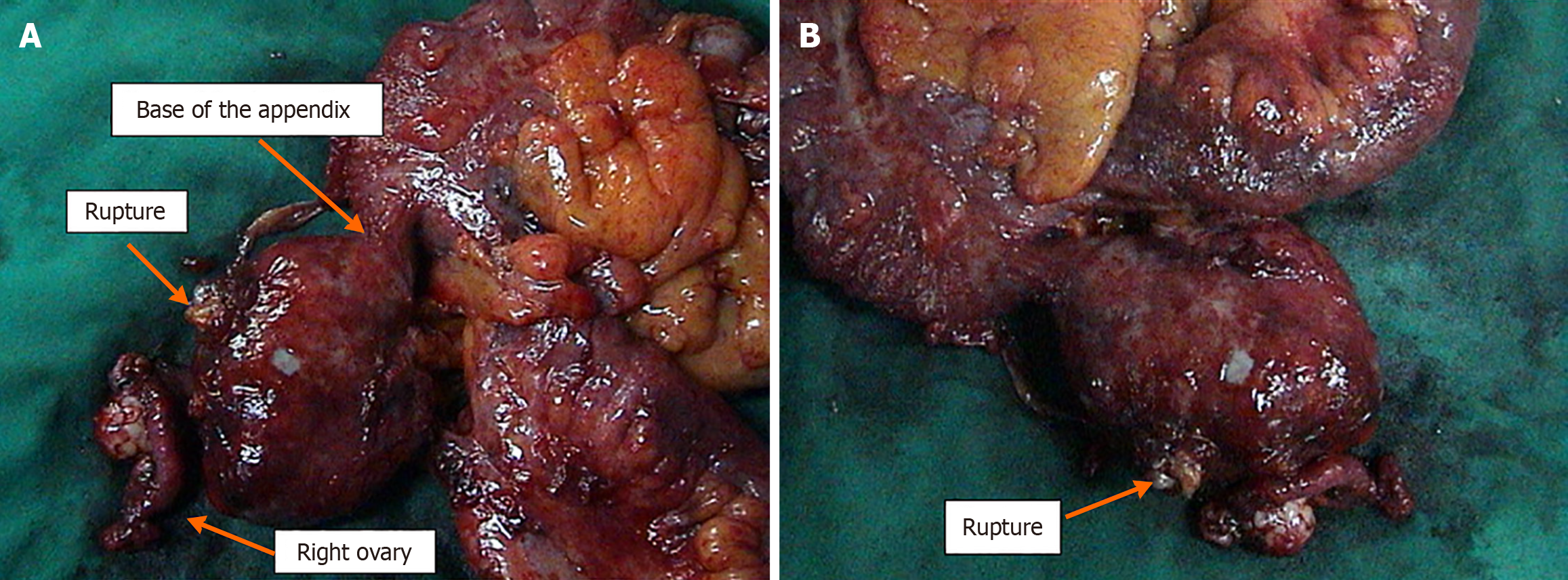

The patient was scheduled for CRS. Intraoperatively, an appendiceal tumor was identified adherent to the right ovary, and a focal perforation of the tumor was seen, which was contained by the abdominal wall. A focal mucinous implant was also noted over the omentum (Figure 7). Surgical management included right hemicolectomy, adnexectomy, complete omentectomy, and division of the umbilicus (Figure 8). The final histological examination showed a focally ruptured appendicular mucocele on mucinous cystadenoma with the absence of malignant cells. Mucoid implants were identified over the greater omentum and abdominal wall resections. The resected bowel and lymph nodes were negative for malignancy (Figure 9).

A diagnostic laparoscopy was performed to assess the abdominal cavity and revealed extensive mucinous ascites. The procedure was converted to laparotomy. The appendix was found to be perforated at its mid-portion with visible mucous secretions. Complete CRS with omentectomy, excision of peritoneal deposits, and appendectomy was performed (Figure 10). Histopathology showed a ruptured mucocele of the appendix, with columnar epithelium demonstrating extensive mucin production in the mucosa. Peritoneal deposits showed mucinous columnar cells without atypia. The postoperative course was uneventful.

The patient underwent appendectomy, and final pathology two weeks later showed an appendicular mucocele with perforation located 3 cm from the appendiceal tip and a healthy appendiceal base. Given the risk of mucinous dissemination, he underwent further evaluation and was subsequently admitted for CRS and HIPEC six weeks after appendectomy. A right-sided Double J stent was placed preoperatively. Exploration of the abdomen revealed no peritoneal, hepatic, or distant deposits. A gelatinous lesion measuring approximately 3 cm × 5 cm was found at the level of the cecum. Liberation of the right and transverse colon was performed after dissection of the line of Toldt, followed by resection of the peritoneum in the hepatorenal fossa and gastrocolic ligament. A large excision of the peritoneum at the level of the cecum was carried out along with resection of mesentery and mesocolon, ligation of the ileocolic artery at its base, and transection of the ileum and transverse colon. Frozen section analysis demonstrated pseudomyxoma. Additional excisions included the right colic peritoneum and the Douglas pouch peritoneum. Two drains were placed on the right and three on the left. Closed-technique HIPEC was performed using oxaliplatin 250 with intravenous 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) at 41 °C to 42 °C for 45 minutes, followed by extensive lavage. The laparotomy incision was reopened for abdominal lavage, and a side-to-side manual ileocolic anastomosis was created. Two drains were left in the subhepatic area and the Douglas pouch (Figure 11).

Exploratory laparoscopy revealed gelatinous collections around the appendix and cecum. Biopsies were taken, and pathology confirmed appendiceal pseudomyxoma. The patient was then prepared for right hemicolectomy with CRS and HIPEC (Figure 12). A midline incision from the subxiphoid to the pubic symphysis was made, with dissection through the fascia and aponeurosis until reaching the peritoneum, which was opened. A right partial colectomy was performed using a GIA 80 mm linear stapler (Covidien, Mansfield, MA, United States), and the specimen was removed. The omentum was dissected and excised. Small lesions were identified on the right diaphragmatic peritoneum and in the Douglas pouch, and these peritoneal surfaces were removed and sent for pathological analysis. Further inspection revealed no additional lesions throughout the abdomen. Two drains were placed on the right and three on the left. Closed-technique HIPEC was performed using oxaliplatin 250 and intravenous 5-FU at a temperature of 41 °C to 42 °C for 45 minutes, followed by extensive lavage. The laparotomy incision was reopened, the abdomen was re-lavaged, and a side-to-side manual ileocolic anastomosis was created. Two drains were left in the subhepatic region and the Douglas pouch.

The postoperative course was uncomplicated. He was discharged home on postoperative day 5. The pathology report revealed low-grade peritoneal mucinous neoplasia grade 1 from an appendiceal primary.

The postoperative course was uncomplicated. Follow-up CT scans at one and two years were free of disease.

Four years later, the patient presented with fatigue, weight loss, and pallor. Enhanced CT scan again showed a large amount of ascites (Figure 13). A repeat laparotomy was performed, revealing large quantities of gelatinous mucinous secretion. Complete CRS with visceral and parietal peritonectomy was carried out (Figure 14). Pathology revealed PMP without malignant cells, and postoperative recovery was uneventful.

One year later, the patient re-presented with fatigue, weight loss, and abdominal distension. Enhanced CT scan showed abundant ascites (Figure 15). A third laparotomy was performed with complete CRS followed by HIPEC using the coliseum technique with suspension of the abdominal walls for 90 minutes. Mitomycin was used at a dose of

The postoperative hospital stay was initially uneventful. On postoperative day 4, the patient developed a fever reaching 39 °C to 40 °C with decreased urine output and abdominal pain. A contrast-enhanced CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis showed a right pleural effusion with atelectasis but no signs of bowel obstruction or intra-abdominal collection. Blood, urine, and wound cultures were obtained and revealed extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli in the wound. Antimicrobial therapy was adjusted according to susceptibility testing, and wound care was administered. The patient remained stable and was discharged home 13 days after surgery.

Final pathology demonstrated a residual focus of PMP in the ileocolic angle measuring 5 cm. The ileal and colonic walls were not invaded, and surgical margins were negative. Peritoneal fluid collected before resection contained atypical cells, whereas fluid obtained after resection contained no tumor elements and only dystrophic mesothelial cells. Additional samples from the right colic peritoneum and Douglas pouch were devoid of tumor. Follow-up at 2 weeks, 1 month, and 6 months postoperatively was unremarkable, and the patient had returned to regular activity.

The postoperative hospital course was uneventful, and the patient was discharged on postoperative day 9 without complications. Follow-up at 2 weeks and 1 month post-operatively was unremarkable, and the patient had returned to regular activity.

In its early stages, an appendiceal mucocele gradually enlarges, eventually obstructing the appendiceal lumen and rupturing, leading to the dissemination of mucinous material within the peritoneal cavity[5]. The disease tends to spread to predictable areas of fluid stasis, such as the pouch of Douglas, paracolic gutters, Morrison’s pouch, the ligament of Treitz, and the recto-vesical pouch, while mobile organs are usually spared[6]. Tumor deposits are also common on the right hemidiaphragm, subdiaphragm, and omentum - sites of high peritoneal fluid reabsorption. Histopathological classification of PMP has long been confusing due to overlapping terminology. Misdraji et al[7] categorized PMP into disseminated peritoneal adenomucinosis (DPAM), peritoneal mucinous carcinomatosis, and hybrid tumors with features of both. DPAM shows abundant mucin and low atypia, while peritoneal mucinous carcinomatosis presents with malignant cytology and proliferative epithelium. Hybrid forms behave biologically like DPAM[8]. In 2010, the American Joint Committee on Cancer and World Health Organization reclassified appendiceal mucinous lesions into low-grade and high-grade PMP based on histogenesis and cytologic features[9-11]. Low-grade PMP displays bland, nonstratified epithelium within mucin pools, whereas high-grade lesions exhibit atypia, signet-ring cells, and desmoplastic stroma[11]. The Peritoneal Surface Oncology Group International consensus (2016) further refined classification into Low-grade Appendiceal Mucinous Neoplasm, High-grade Appendiceal Mucinous Neoplasm, and four PMP subtypes: Acellular mucin, Low-grade Mucinous Carcinoma Peritonei, High-grade Mucinous Carcinoma Peritonei, and High-grade Mu

PMP’s clinical presentation is variable and nonspecific, often mimicking other abdominal disorders. About 27% of patients present with appendicitis, 23% with abdominal distention, and 14% with hernia, while others are diagnosed incidentally[13,14]. Contrast-enhanced CT of the chest, abdomen, and pelvis is the imaging modality of choice[15]. CT identifies rupture, calcification, mucin ascites, omental caking, and the classic “hepatic scalloping” sign. It also helps evaluate small bowel involvement, crucial for determining cytoreduction (CC) feasibility[3,16]. In case 1, hepatic scalloping suggested PMP, later confirmed by MRI. MRI demonstrates higher sensitivity than CT for small lesions (< 1 cm), reaching 85%-90% when advanced sequences (diffusion weighted imaging, fat suppression, delayed gadolinium) are used[15,17-21]. Although CT remains the first-line modality, ultrasound can assist preoperatively in assessing organ boundaries and resectability, though mesenteric involvement may be underestimated[22].

Serum tumor markers - CEA, CA 19-9, and CA 125 - are valuable for prognosis and recurrence monitoring[23]. Elevated levels correlate with poorer outcomes; CA 19-9 > 1000 U/mL carries a 5-year survival of 23% vs 90% when < 100 U/mL[24]. Elevated markers predict recurrence and worse survival[25-29]. Ascitic fluid markers are even more sensitive for diagnosis and can help determine tumor origin[30]. Tumor-stromal ratio and Ki-67 expression have also emerged as prognostic indicators; a higher tumor-stromal ratio correlates with aggressive biology[31,32].

Before the 1990s, treatment was limited to debulking and drainage, with high recurrence rates[33]. Currently, standard management consists of CRS followed by HIPEC, which eradicates microscopic residual disease[34]. Completeness of cytoreduction (CC) is scored by residual tumor size: CC0 (none), CC1 (< 0.25 cm), CC2 (0.25-2.5 cm), and CC3 (> 2.5 cm); CC0-1 indicates complete cytoreduction[3,35,36]. Disease extent is quantified using the PCI, summing lesion scores (0-3) from 13 regions[37,38].

HIPEC is delivered via open “coliseum” or closed techniques, perfusing heated chemotherapy (41 °C to 42 °C) for 60-90 minutes[39]. Tumor cells are preferentially destroyed due to thermosensitivity[40,41]. Agents used include mitomycin C, cisplatin, carboplatin, 5-FU, and taxanes[40]. In our cases, HIPEC regimens included mitomycin C or oxaliplatin + 5-FU, depending on the technique. The 2020 Chicago Consensus recommends agent selection based on comorbidities[42]. Early postoperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy (EPIC) may further improve outcomes. Menassel et al[43] showed a median survival benefit (34.3 months) for HIPEC + EPIC compared to HIPEC alone. EPIC with 5-FU is administered on pos

Prognosis depends on multiple factors, including age, tumor origin, and CC. Chen et al[4] developed nomograms using 4959 patients, showing that age > 53 years and non-appendiceal origin predicted worse survival, while race, sex, and radiotherapy did not. Serum tumor markers remain key prognostic tools. In a systematic review, Klumpp et al[46] reported 5-year mortality rates of 28.8% for low-grade and 55.9% for high-grade PMP, with disease-free survival of 43% and 20%, respectively. After the adoption of CRS + HIPEC, survival improved dramatically: 5-year overall survival of 90% in low-grade and 70% in high-grade PMP[47]. Recent studies show 5-year overall survival and 10-year overall survival of 87.4% and 70.3% with CRS + HIPEC vs 39.2% and 8.1% for debulking alone[48].

Despite optimal CRS and HIPEC, recurrence occurs in approximately 25% of patients, mostly within 5 years[49]. A cohort of 948 patients showed 24.2% recurrence, emphasizing the need for long-term follow-up - ideally 10 years, as 10% recur after 5 years[50]. In our case 3, recurrence at year 4 underscores this point. Annual imaging (CT or MRI) with serum marker monitoring is standard. Recurrent disease management depends on tumor burden and patient fitness and may include repeat CRS + HIPEC, systemic therapy, or observation. Recent international consensus guidelines and reviews published after 2020 continue to endorse complete CRS followed by HIPEC as the standard of care for resectable PMP, with treatment individualization based on tumor grade, PCI, and patient fitness[50-53].

In the present series, three patients experienced disease recurrence, highlighting the chronic and relapsing nature of PMP. Notably, all recurrent cases shared several common characteristics. First, the initial disease burden was high, with extensive mucinous dissemination at presentation, reflected by elevated PCI scores when available (case 1: PCI 25/39; case 3: Diffuse ascites and widespread peritoneal involvement). Second, although complete cytoreduction was achieved in the initial procedures, microscopic residual disease and tumor biology likely contributed to recurrence, particularly in patients with repeated mucinous accumulation over time. Case 3 demonstrated multiple recurrences at 4, 5, and 8 years, ultimately progressing to invasive adenocarcinoma, underscoring the potential for biologic evolution in PMP despite aggressive surgical management. Third, recurrent cases required repeat CRS, with acceptable perioperative outcomes, supporting existing evidence that iterative CRS ± HIPEC remains a viable strategy in selected patients with preserved performance status and resectable disease. These findings emphasize the importance of long-term surveillance beyond five years, particularly in patients with high initial tumor burden.

PMP is a rare, disputable malignant mucinous neoplasm originating from a perforated appendix, with secondary peritoneal distribution. The most efficient treatment of PMP includes optimal CRS + HIPEC. This treatment has allowed patients with PMP higher disease-free survival and overall survival rates. Even high burden diseases may be manageable with surgical resection, and in case complete excision cannot be achieved, maximal debulking significantly increases patient survival. PMP treatment techniques have also allowed the development of similar management in treating other malignancies, such as colorectal peritoneal metastasis. However, PMP research is still in its early stages, and further investigations are needed to identify poor prognostic features to navigate targeted treatment options and prevent disease progression and/or recurrence. These findings are consistent with contemporary international consensus guidelines and recent high-quality observational studies supporting CRS + HIPEC as the cornerstone of PMP management.

The authors acknowledge the clinical staff and supporting departments whose work contributed to the care of the patients described in this case series.

| 1. | Darr U, Renno A, Alkully T, Khan Z, Tiwari A, Zeb W, Purdy J, Nawras A. Diagnosis of Pseudomyxoma peritonei via endoscopic ultrasound guided fine needle aspiration: a case report and review of literature. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2017;52:609-612. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Castle OL. Cystic dilation of the vermiform appendix. Ann Surg. 1915;61:582-588. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Dayal S, Taflampas P, Riss S, Chandrakumaran K, Cecil TD, Mohamed F, Moran BJ. Complete cytoreduction for pseudomyxoma peritonei is optimal but maximal tumor debulking may be beneficial in patients in whom complete tumor removal cannot be achieved. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:1366-1372. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Chen P, Su L, Yang W, Zhang J, Wang Y, Wang C, Yu Y, Yang L, Zhou Z. Development and validation of prognostic nomograms for pseudomyxoma peritonei patients after surgery: A population-based study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2020;99:e20963. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Krivsky LA. On the Pseudomyxoma Peritonei. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1921;28:204-227. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Pandey A, Mishra AK. Pseudomyxoma peritonei: disseminated peritoneal adenomucinosis variant. BMJ Case Rep. 2011;2011:bcr0720103181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Misdraji J. Mucinous epithelial neoplasms of the appendix and pseudomyxoma peritonei. Mod Pathol. 2015;28 Suppl 1:S67-S79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Panarelli NC, Yantiss RK. Mucinous neoplasms of the appendix and peritoneum. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2011;135:1261-1268. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Mercier F, Dagbert F, Pocard M, Goéré D, Quenet F, Wernert R, Dumont F, Brigand C, Passot G, Glehen O; RENAPE Network. Recurrence of pseudomyxoma peritonei after cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. BJS Open. 2019;3:195-202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 47] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Carr NJ, Cecil TD, Mohamed F, Sobin LH, Sugarbaker PH, González-Moreno S, Taflampas P, Chapman S, Moran BJ; Peritoneal Surface Oncology Group International. A Consensus for Classification and Pathologic Reporting of Pseudomyxoma Peritonei and Associated Appendiceal Neoplasia: The Results of the Peritoneal Surface Oncology Group International (PSOGI) Modified Delphi Process. Am J Surg Pathol. 2016;40:14-26. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 360] [Cited by in RCA: 549] [Article Influence: 54.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sugarbaker PH. Pseudomyxoma peritonei. A cancer whose biology is characterized by a redistribution phenomenon. Ann Surg. 1994;219:109-111. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 178] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Moran BJ, Cecil TD. The etiology, clinical presentation, and management of pseudomyxoma peritonei. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2003;12:585-603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 171] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Järvinen P, Lepistö A. Clinical presentation of pseudomyxoma peritonei. Scand J Surg. 2010;99:213-216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Smeenk RM, van Velthuysen ML, Verwaal VJ, Zoetmulder FA. Appendiceal neoplasms and pseudomyxoma peritonei: a population based study. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2008;34:196-201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 309] [Cited by in RCA: 392] [Article Influence: 20.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 15. | Sulkin TV, O'Neill H, Amin AI, Moran B. CT in pseudomyxoma peritonei: a review of 17 cases. Clin Radiol. 2002;57:608-613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 86] [Cited by in RCA: 82] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Jacquet P, Jelinek JS, Chang D, Koslowe P, Sugarbaker PH. Abdominal computed tomographic scan in the selection of patients with mucinous peritoneal carcinomatosis for cytoreductive surgery. J Am Coll Surg. 1995;181:530-538. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Mittal R, Chandramohan A, Moran B. Pseudomyxoma peritonei: natural history and treatment. Int J Hyperthermia. 2017;33:511-519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 134] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Sun P, Li X, Wang L, Wang R, Du X. Enhanced computed tomography imaging features predict tumor grade in pseudomyxoma peritonei. Quant Imaging Med Surg. 2022;12:2321-2331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Cotton F, Pellet O, Gilly FN, Granier A, Sournac L, Glehen O. MRI evaluation of bulky tumor masses in the mesentery and bladder involvement in peritoneal carcinomatosis. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2006;32:1212-1216. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Tirumani SH, Fraser-Hill M, Auer R, Shabana W, Walsh C, Lee F, Ryan JG. Mucinous neoplasms of the appendix: a current comprehensive clinicopathologic and imaging review. Cancer Imaging. 2013;13:14-25. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 104] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 7.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 21. | Low RN, Barone RM, Gurney JM, Muller WD. Mucinous appendiceal neoplasms: preoperative MR staging and classification compared with surgical and histopathologic findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2008;190:656-665. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Alejandra Maestro Durán M, Costas Mora M, Méndez Díaz C, Fernández Blanco C, María Álvarez Seoane R, Soler Fernández R, Rodríguez García E. Role and usefulness of mr imaging in the assessment of peritoneal carcinomatosis. Eur J Radiol. 2022;156:110519. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Sofia C, Marino MA, Milone E, Ieni A, Blandino A, Ascenti G, Macrì A. Pseudomyxoma peritonei involving the canal of Nuck: The added value of magnetic resonance imaging for detection and presurgical planning. Radiol Case Rep. 2022;17:1887-1889. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Liang L, Han X, Zhou N, Xu H, Guo J, Zhang Q. Ultrasound for Preoperatively Predicting Pathology Grade, Complete Cytoreduction Possibility, and Survival Outcomes of Pseudomyxoma Peritonei. Front Oncol. 2021;11:690178. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Esquivel J, Sugarbaker PH. Clinical presentation of the Pseudomyxoma peritonei syndrome. Br J Surg. 2000;87:1414-1418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 146] [Cited by in RCA: 149] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Wagner PL, Austin F, Sathaiah M, Magge D, Maduekwe U, Ramalingam L, Jones HL, Holtzman MP, Ahrendt SA, Zureikat AH, Pingpank JF, Zeh HJ 3rd, Bartlett DL, Choudry HA. Significance of serum tumor marker levels in peritoneal carcinomatosis of appendiceal origin. Ann Surg Oncol. 2013;20:506-514. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Taflampas P, Dayal S, Chandrakumaran K, Mohamed F, Cecil TD, Moran BJ. Pre-operative tumour marker status predicts recurrence and survival after complete cytoreduction and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy for appendiceal Pseudomyxoma Peritonei: Analysis of 519 patients. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2014;40:515-520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 6.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Koh JL, Liauw W, Chua T, Morris DL. Carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9) is an independent prognostic indicator in pseudomyxoma peritonei post cytoreductive surgery and perioperative intraperitoneal chemotherapy. J Gastrointest Oncol. 2013;4:173-181. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Alexander-Sefre F, Chandrakumaran K, Banerjee S, Sexton R, Thomas JM, Moran B. Elevated tumour markers prior to complete tumour removal in patients with pseudomyxoma peritonei predict early recurrence. Colorectal Dis. 2005;7:382-386. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Carmignani CP, Hampton R, Sugarbaker CE, Chang D, Sugarbaker PH. Utility of CEA and CA 19-9 tumor markers in diagnosis and prognostic assessment of mucinous epithelial cancers of the appendix. J Surg Oncol. 2004;87:162-166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 84] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | van Ruth S, Hart AA, Bonfrer JM, Verwaal VJ, Zoetmulder FA. Prognostic value of baseline and serial carcinoembryonic antigen and carbohydrate antigen 19.9 measurements in patients with pseudomyxoma peritonei treated with cytoreduction and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Ann Surg Oncol. 2002;9:961-967. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Kusamura S, Baratti D, Hutanu I, Gavazzi C, Morelli D, Iusco DR, Grassi A, Bonomi S, Virzì S, Haeusler E, Deraco M. The role of baseline inflammatory-based scores and serum tumor markers to risk stratify pseudomyxoma peritonei patients treated with cytoreduction (CRS) and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC). Eur J Surg Oncol. 2015;41:1097-1105. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Canbay E, Ishibashi H, Sako S, Mizumoto A, Hirano M, Ichinose M, Takao N, Yonemura Y. Preoperative carcinoembryonic antigen level predicts prognosis in patients with pseudomyxoma peritonei treated with cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. World J Surg. 2013;37:1271-1276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Kusamura S, Hutanu I, Baratti D, Deraco M. Circulating tumor markers: predictors of incomplete cytoreduction and powerful determinants of outcome in pseudomyxoma peritonei. J Surg Oncol. 2013;108:1-8. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Wang B, Ma R, Rao B, Xu H. Serum and ascites tumor markers in the diagnostic and prognostic prediction for appendiceal pseudomyxoma peritonei. BMC Cancer. 2023;23:90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Ma R, Lin YL, Li XB, Yan FC, Xu HB, Peng Z, Li Y. Tumor-stroma ratio as a new prognosticator for pseudomyxoma peritonei: a comprehensive clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study. Diagn Pathol. 2021;16:116. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Li LT, Jiang G, Chen Q, Zheng JN. Ki67 is a promising molecular target in the diagnosis of cancer (review). Mol Med Rep. 2015;11:1566-1572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 315] [Cited by in RCA: 596] [Article Influence: 49.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Smeenk RM, Verwaal VJ, Zoetmulder FA. Pseudomyxoma peritonei. Cancer Treat Rev. 2007;33:138-145. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 39. | Sugarbaker PH, Zhu BW, Sese GB, Shmookler B. Peritoneal carcinomatosis from appendiceal cancer: results in 69 patients treated by cytoreductive surgery and intraperitoneal chemotherapy. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36:323-329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Chua TC, Moran BJ, Sugarbaker PH, Levine EA, Glehen O, Gilly FN, Baratti D, Deraco M, Elias D, Sardi A, Liauw W, Yan TD, Barrios P, Gómez Portilla A, de Hingh IH, Ceelen WP, Pelz JO, Piso P, González-Moreno S, Van Der Speeten K, Morris DL. Early- and long-term outcome data of patients with pseudomyxoma peritonei from appendiceal origin treated by a strategy of cytoreductive surgery and hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2449-2456. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 658] [Cited by in RCA: 817] [Article Influence: 58.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Sugarbaker PH. Peritonectomy procedures. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2003;12:703-727, xiii. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 127] [Cited by in RCA: 142] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Jacquet P, Sugarbaker PH. Clinical research methodologies in diagnosis and staging of patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis. Cancer Treat Res. 1996;82:359-374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 958] [Cited by in RCA: 1177] [Article Influence: 39.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Menassel B, Duclos A, Passot G, Dohan A, Payet C, Isaac S, Valette PJ, Glehen O, Rousset P. Preoperative CT and MRI prediction of non-resectability in patients treated for pseudomyxoma peritonei from mucinous appendiceal neoplasms. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2016;42:558-566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Bhatt A, Yonemura Y, Mehta S, Benzerdjeb N, Kammar P, Parikh L, Prabhu A, Mishra S, Shah M, Shaikh S, Kepenekian V, Bonnefoy I, Patel MD, Isaac S, Glehen O. The Pathologic Peritoneal Cancer Index (PCI) Strongly Differs From the Surgical PCI in Peritoneal Metastases Arising From Various Primary Tumors. Ann Surg Oncol. 2020;27:2985-2996. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Llueca A, Escrig J; MUAPOS working group (Multidisciplinary Unit of Abdominal Pelvic Oncology Surgery). Prognostic value of peritoneal cancer index in primary advanced ovarian cancer. Eur J Surg Oncol. 2018;44:163-169. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Klumpp B, Aschoff P, Schwenzer N, Koenigsrainer I, Beckert S, Claussen CD, Miller S, Koenigsrainer A, Pfannenberg C. Correlation of preoperative magnetic resonance imaging of peritoneal carcinomatosis and clinical outcome after peritonectomy and HIPEC after 3 years of follow-up: preliminary results. Cancer Imaging. 2013;13:540-547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Narasimhan V, Wilson K, Britto M, Warrier S, Lynch AC, Michael M, Tie J, Akhurst T, Mitchell C, Ramsay R, Heriot A. Outcomes Following Cytoreduction and HIPEC for Pseudomyxoma Peritonei: 10-Year Experience. J Gastrointest Surg. 2020;24:899-906. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Crestani A, Benoit L, Touboul C, Pasquier J. Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC): Should we look closer at the microenvironment? Gynecol Oncol. 2020;159:285-294. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | González-Moreno S, González-Bayón LA, Ortega-Pérez G. Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy: Rationale and technique. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2010;2:68-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 176] [Cited by in RCA: 199] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (8)] |

| 50. | Ye S, Zheng S. Comprehensive Understanding and Evolutional Therapeutic Schemes for Pseudomyxoma Peritonei: A Literature Review. Am J Clin Oncol. 2022;45:223-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Lin YL, Xu DZ, Li XB, Yan FC, Xu HB, Peng Z, Li Y. Consensuses and controversies on pseudomyxoma peritonei: a review of the published consensus statements and guidelines. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2021;16:85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Hayler R, Lockhart K, Barat S, Cheng E, Mui J, Shamavonian R, Ahmadi N, Alzahrani N, Liauw W, Morris D. Survival benefits with EPIC in addition to HIPEC for low grade appendiceal neoplasms with pseudomyxoma peritonei: a propensity score matched study. Pleura Peritoneum. 2023;8:27-35. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Sommariva A, Tonello M, Rigotto G, Lazzari N, Pilati P, Calabrò ML. Novel Perspectives in Pseudomyxoma Peritonei Treatment. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13:5965. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/