Published online Jan 26, 2026. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v14.i3.117276

Revised: December 24, 2025

Accepted: January 14, 2026

Published online: January 26, 2026

Processing time: 50 Days and 8.7 Hours

Streptococcus bovis (S. bovis) bacteremia and infective endocarditis have a well-established association with colorectal cancer (CRC), though the mechanisms underlying this potentially bidirectional relationship remain poorly understood.

This case report describes a 55-year-old male with a history of hypertension and hemicolectomy due to advanced colorectal adenomas who presented with syn

This presentation underscores how CRC-induced mucosal disruption may pre

Core Tip: This case report illustrates the well-recognized but still poorly understood link between Streptococcus bovis (S. bovis) infection and colorectal cancer (CRC). By detailing a patient who developed S. bovis bacteremia and dual-valve endocarditis in the setting of a small, localized cecal adenocarcinoma, the case provides insight into how early mucosal disruption from CRC may facilitate bacterial translocation and systemic infection. The report underscores the necessity of prompt colorectal evaluation in all patients with S. bovis bacteremia-even without gastrointestinal symptoms-and highlights the potential role of S. bovis both as a biomarker and a participant in CRC pathogenesis.

- Citation: Nguyen-Ngo K, Majmudar VH, Jain A, Manem N, Donovan K, Tadros M. Streptococcus bovis endocarditis secondary to colorectal cancer: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2026; 14(3): 117276

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v14/i3/117276.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v14.i3.117276

Colorectal cancer (CRC) remains a significant health burden in the United States, serving as the third-most diagnosed cancer in both men and women, as well as the second leading cause of overall cancer death. While obesity, physical inactivity, and low-fiber, highly processed diets have previously been highlighted as risk factors, the molecular pa

Streptococcus bovis (S. bovis), which belongs to the group D Streptococci family, represents a normal component of the gut microbiome, and is classically linked to endocarditis and bacteremia[7]. A clinically significant association exists between S. bovis infection and CRC, as up to 80% of patients with S. bovis infection are found to have concurrent colonic neoplasms upon endoscopic evaluation, ranging from adenomas to invasive carcinomas[8]. This relationship may be bidirectional, with S. bovis patients being at higher risk of harboring CRC, in addition to CRC patients being more susceptible to S. bovis colonization, suggesting a possible role in CRC tumorigenesis[8,9].

It remains unclear whether S. bovis fosters a carcinogenic environment through mechanisms like toxic byproducts and chronic inflammation, or if CRC-induced disruptions in colonic mucosa increase susceptibility to preferential bacterial translocation. To that end, we report a case that offers insight into underlying disease pathogenesis.

A 55-year-old male presented to the emergency department with syncope, septic shock, and a 12-pound weight loss over the past three weeks.

The patient developed syncope and stated that he has been able to tolerate only minimal amounts of food and fluids.

The patient has a past medical history of hypertension, asthma, bipolar disorder, bowel replacement, and colon cancer status post-hemicolectomy.

The patient is a non-smoker and non-drinker. He has a family history of an unknown cancer in his mother, as well as colon cancer in his aunt and uncle. He does not regularly follow-up with his primary care provider, and his last colo

The patient was 167 cm tall and weighed 97 kg. On admission, the patient was tachycardic with a heart rate of 97 beats per minute, blood pressure of 106/63 mmHg (14.1/8.4 kPa), respiratory rate of 20/minute, oxygen saturation of 95%, and body temperature of 36.8 °C. Physical examination revealed mild epigastric discomfort to deep palpation without gu

Laboratory evaluation was notable for initial leukocytosis and microcytic anemia, in addition to hypoproteinemia, hypocalcemia, and mild hyperglycemia (Table 1).

| Parameter | Result | Reference range | Interpretation |

| WBC | 5.1 × 103/µL (initial 185) | 3.9-10.6 × 103/µL | Initially high, normalized |

| Hemoglobin | 9.2 g/dL | 13.5-17.0 g/dL | ↓ |

| Hematocrit | 27% | 41%-53% | ↓ |

| Platelets | 225 × 103/µL | 130-400 × 103/µL | Normal |

| Sodium | 139 mEq/L | 135-145 mEq/L | Normal |

| Potassium | 3.6 mEq/L | 3.5-5.0 mEq/L | Normal |

| BUN | 3 mg/dL | 6-22 mg/dL | ↓ |

| Creatinine | 0.67 mg/dL | 0.60-1.30 mg/dL | Normal |

| Calcium | 8.3 mg/dL | 8.5-10.5 mg/dL | ↓ |

| Total protein | 5.3 g/dL | 6.0-8.0 mg/dL | ↓ |

| Glucose | 103 mg/dL | 65-99 mg/dL | Slight ↑ |

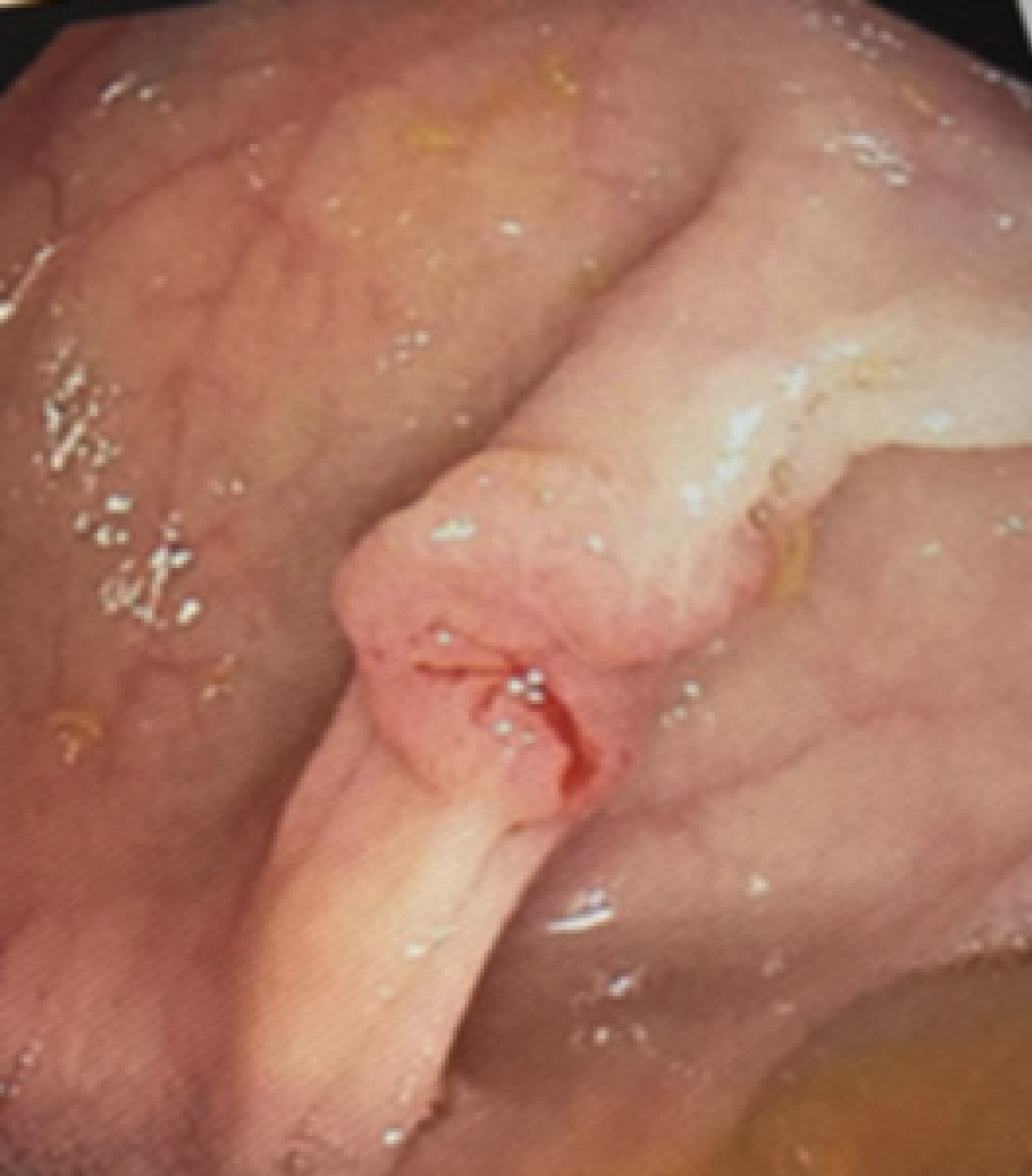

Standard blood culture panels grew S. bovis. A transthoracic echocardiogram demonstrated mobile vegetations on both the aortic and mitral valves, consistent with infective endocarditis. Given the S. bovis bacteremia, gastroenterology was consulted. Colonoscopy revealed a 1 cm fungating, sessile, ulcerated, non-obstructing mass in the cecum, appearing scirrhous-like and depressed centrally. Biopsy showed moderately differentiated adenocarcinoma with 1.2 cm sub

A diagnosis of S. bovis infection with concurrent colorectal adenocarcinoma was established.

The patient was started on intravenous ceftriaxone for 6 weeks, per Infective Endocarditis guidelines. Cardiothoracic surgery performed a repair of both aortic and mitral valves. Following stabilization, he underwent laparoscopic right hemicolectomy on the same day, which revealed negative margins and no nodal spread.

His recovery was uneventful, and he was discharged on postoperative day 5 with follow-up in cardiology and gastroenterology clinics.

S. bovis, a bacterial strain that is a component of healthy gut flora, elicits an eight-fold increase in CRC development. Prior research has found that 51% of patients with S. bovis bacteremia had concurrent adenocarcinoma, with the most common site of malignancy in the sigmoid colon. Similarly, literature reports that 18%-62% of patients with S. bovis infective endocarditis had colorectal tumors[7-9]. Despite this well-established link, the pathophysiology underlying the rela

S. bovis not only exhibits adhesive properties, allowing the bacteria to colonize intestinal cells, but also uniquely grows in bile, unlike many of its alpha-hemolytic streptococci counterparts[10]. Furthermore, its ability to bypass filtration by the hepatic reticulo-endothelial system accelerates its entry into the systemic circulation[11]. S. bovis also displays a high affinity for extracellular matrix proteins, particularly type 1 collagen, which is abundantly expressed at sites of tissue injury, remodeling, or inflammation, such as heart valve vegetations and tumors[12,13]. In bacteremia, S. bovis utilizes pili to attach to mucosal epithelial cells for ease of translocation, ultimately facilitating formation of biofilm on damaged heart valves and precancerous epithelium[12-14].

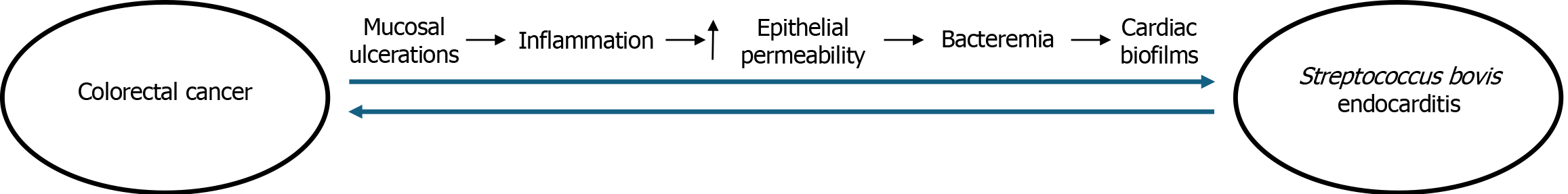

This case study proposes a novel pathogenetic mechanism between S. bovis and CRC. (Figure 2). Given the patient’s history of advanced adenomas, it is likely that the invasive cancer developed first and the CRC-induced disruption in mucosal protective barriers subsequently increased susceptibility of a S. bovis invasion into tissues. In response to tumor-related injury, immune activation triggered the release of pro-inflammatory mediators, further increasing epithelial permeability and leading to bacteremia. As S. bovis displays a notable predilection for the cardiac endothelium, it most likely formed biofilms on the patient’s aortic and mitral valves, which ultimately manifested as the vegetations observed on echocardiogram findings. Our hypothesis is supported by the small tumor size and the absence of lymph node involvement, suggesting an early-stage malignancy with localized disruption of the mucosal barrier.

In this patient, the systemic infection ultimately necessitated dual valve repair and right hemicolectomy. His favorable recovery following antibiotic therapy, valve repair, and tumor resection further supports a model in which colorectal malignancy preceded bacterial invasion, with management targeting both the infectious complication and the underlying neoplastic source. Notably, prior research has hypothesized an etiological role of S. bovis in the neoplastic transformation of colonic mucosa, whether through an increased inflammatory load or pili attachment to precancerous colonic lesions[15,16]. To that end, this relationship is likely bidirectional; the presence of one condition may exacerbate or facilitate the presence of the other, highlighting a complex interplay in which CRC and S. bovis infection may mutually enforce disease progression.

This case highlights the complex and tightly bidirectional relationship between S. bovis and CRC. While S. bovis infection has been widely recognized as a clinical marker warranting colorectal evaluation, this case supports a sequence in which colorectal adenocarcinoma preceded the onset of bacteremia and infective endocarditis. The patient’s history of advanced adenomas and the subsequent development of a small, localized, non-obstructing cecal tumor with no lymph node involvement suggests that insult to the mucosal barrier by malignancy may have facilitated translocation of S. bovis into the bloodstream. This report reinforces the importance of prompt gastrointestinal evaluation in all patients with S. bovis bacteremia, even in the absence of overt gastrointestinal symptoms, as early detection of potential colorectal neoplasia can significantly impact treatment outcomes. Furthermore, these findings add to the growing body of evidence proposing that S. bovis may serve as both a biomarker and facilitator of disease progression. Further research is needed to fully elucidate the causative vs opportunistic role of S. bovis in colorectal carcinogenesis, as well as explore its potential for both preventative and therapeutic intervention.

| 1. | Roshandel G, Ghasemi-Kebria F, Malekzadeh R. Colorectal Cancer: Epidemiology, Risk Factors, and Prevention. Cancers (Basel). 2024;16:1530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 190] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Kasi A, Handa S, Bhatti S, Umar S, Bansal A, Sun W. Molecular Pathogenesis and Classification of Colorectal Carcinoma. Curr Colorectal Cancer Rep. 2020;16:97-106. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Grady WM, Markowitz SD. The molecular pathogenesis of colorectal cancer and its potential application to colorectal cancer screening. Dig Dis Sci. 2015;60:762-772. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 12.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Nguyen LH, Goel A, Chung DC. Pathways of Colorectal Carcinogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:291-302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 344] [Cited by in RCA: 386] [Article Influence: 64.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Sinicrope FA, Sargent DJ. Molecular pathways: microsatellite instability in colorectal cancer: prognostic, predictive, and therapeutic implications. Clin Cancer Res. 2012;18:1506-1512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 172] [Cited by in RCA: 235] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Taieb J, Svrcek M, Cohen R, Basile D, Tougeron D, Phelip JM. Deficient mismatch repair/microsatellite unstable colorectal cancer: Diagnosis, prognosis and treatment. Eur J Cancer. 2022;175:136-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 149] [Cited by in RCA: 198] [Article Influence: 49.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Paritsky M, Pastukh N, Brodsky D, Isakovich N, Peretz A. Association of Streptococcus bovis presence in colonic content with advanced colonic lesion. World J Gastroenterol. 2015;21:5663-5667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Abdulamir AS, Hafidh RR, Abu Bakar F. The association of Streptococcus bovis/gallolyticus with colorectal tumors: the nature and the underlying mechanisms of its etiological role. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2011;30:11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 232] [Cited by in RCA: 254] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 9. | Taylor JC, Kumar R, Xu J, Xu Y. A pathogenicity locus of Streptococcus gallolyticus subspecies gallolyticus. Sci Rep. 2023;13:6291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Corredoira J, Miguez E, Mateo LM, Fernández-Rodríguez R, García-Rodríguez JF, Pérez-González A, Sanjurjo A, Pulian MV, Ayuso-García B; In behalf all members of GESBOGA group. The interaction between liver cirrhosis, infection by Streptococcus bovis, and colon cancer. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2023;42:907-912. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Vaska VL, Faoagali JL. Streptococcus bovis bacteraemia: identification within organism complex and association with endocarditis and colonic malignancy. Pathology. 2009;41:183-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Sillanpää J, Nallapareddy SR, Singh KV, Ferraro MJ, Murray BE. Adherence characteristics of endocarditis-derived Streptococcus gallolyticus ssp. gallolyticus (Streptococcus bovis biotype I) isolates to host extracellular matrix proteins. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2008;289:104-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Sillanpää J, Nallapareddy SR, Qin X, Singh KV, Muzny DM, Kovar CL, Nazareth LV, Gibbs RA, Ferraro MJ, Steckelberg JM, Weinstock GM, Murray BE. A collagen-binding adhesin, Acb, and ten other putative MSCRAMM and pilus family proteins of Streptococcus gallolyticus subsp. gallolyticus (Streptococcus bovis Group, biotype I). J Bacteriol. 2009;191:6643-6653. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Jans C, Boleij A. The Road to Infection: Host-Microbe Interactions Defining the Pathogenicity of Streptococcus bovis/Streptococcus equinus Complex Members. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Biarc J, Nguyen IS, Pini A, Gossé F, Richert S, Thiersé D, Van Dorsselaer A, Leize-Wagner E, Raul F, Klein JP, Schöller-Guinard M. Carcinogenic properties of proteins with pro-inflammatory activity from Streptococcus infantarius (formerly S.bovis). Carcinogenesis. 2004;25:1477-1484. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 154] [Cited by in RCA: 167] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Boleij A, Muytjens CM, Bukhari SI, Cayet N, Glaser P, Hermans PW, Swinkels DW, Bolhuis A, Tjalsma H. Novel clues on the specific association of Streptococcus gallolyticus subsp gallolyticus with colorectal cancer. J Infect Dis. 2011;203:1101-1109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/