Published online Jan 26, 2026. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v14.i3.117257

Revised: December 17, 2025

Accepted: December 26, 2025

Published online: January 26, 2026

Processing time: 50 Days and 20.9 Hours

Prolonged exposure to microgravity profoundly influences ocular physiology, giving rise to spaceflight-associated neuro-ocular syndrome (SANS), a significant concern for astronauts on long-duration missions. This review consolidates current evidence on ocular adaptations to spaceflight, encompassing patho

Core Tip: Vision is mission-critical in human spaceflight. Prolonged exposure to microgravity causes a distinct set of ocular changes known as spaceflight-associated neuro-ocular syndrome. These include optic disc edema, posterior globe flattening, choroidal folds, retinal nerve fiber layer thickening, and hyperopic refractive shifts. Evidence suggests spaceflight-associated neuro-ocular syndrome arises from cephalad fluid shifts, venous congestion, and altered cerebrospinal fluid dynamics rather than raised intracranial pressure alone. Advances in in-flight imaging and artificial intelligence are improving early detection, making ocular health central to safe space exploration and neuro-ophthalmic research.

- Citation: Khullar S, Morya AK, Aggarwal S, Gupta T, Priyanka P, Morya R. Ocular health in outer space and beyond gravity: A minireview. World J Clin Cases 2026; 14(3): 117257

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v14/i3/117257.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v14.i3.117257

The human eye is uniquely vulnerable in space, and recent research has revealed that vision-related changes represent one of the most pressing health risks for astronauts. Since the first systematic reports of optic disc edema, posterior globe flattening, choroidal folds, and hyperopic shifts in astronauts returning from long-duration International Space Station missions, the cluster of findings now recognized as spaceflight-associated neuro-ocular syndrome (SANS) has become a major focus of National Aeronautics and Space Administration risk assessment[1,2]. Epidemiological studies report that SANS occurs in approximately 29%-30% of astronauts following short-duration missions (n approximately of 30-40) and in up to 60%-70% of astronauts after long-duration International Space Station missions (n approximately of 50-60), underscoring the clinical relevance of this condition. Reported hyperopic shifts range from + 0.5 diopters to + 1.5 diopters, documented across small astronaut cohorts, reflecting limitations inherent to spaceflight research. These changes are not simply incidental; they can persist long after return to Earth and pose operational hazards since high-precision vision is essential for spacecraft navigation, extravehicular activities, and experimental tasks[3].

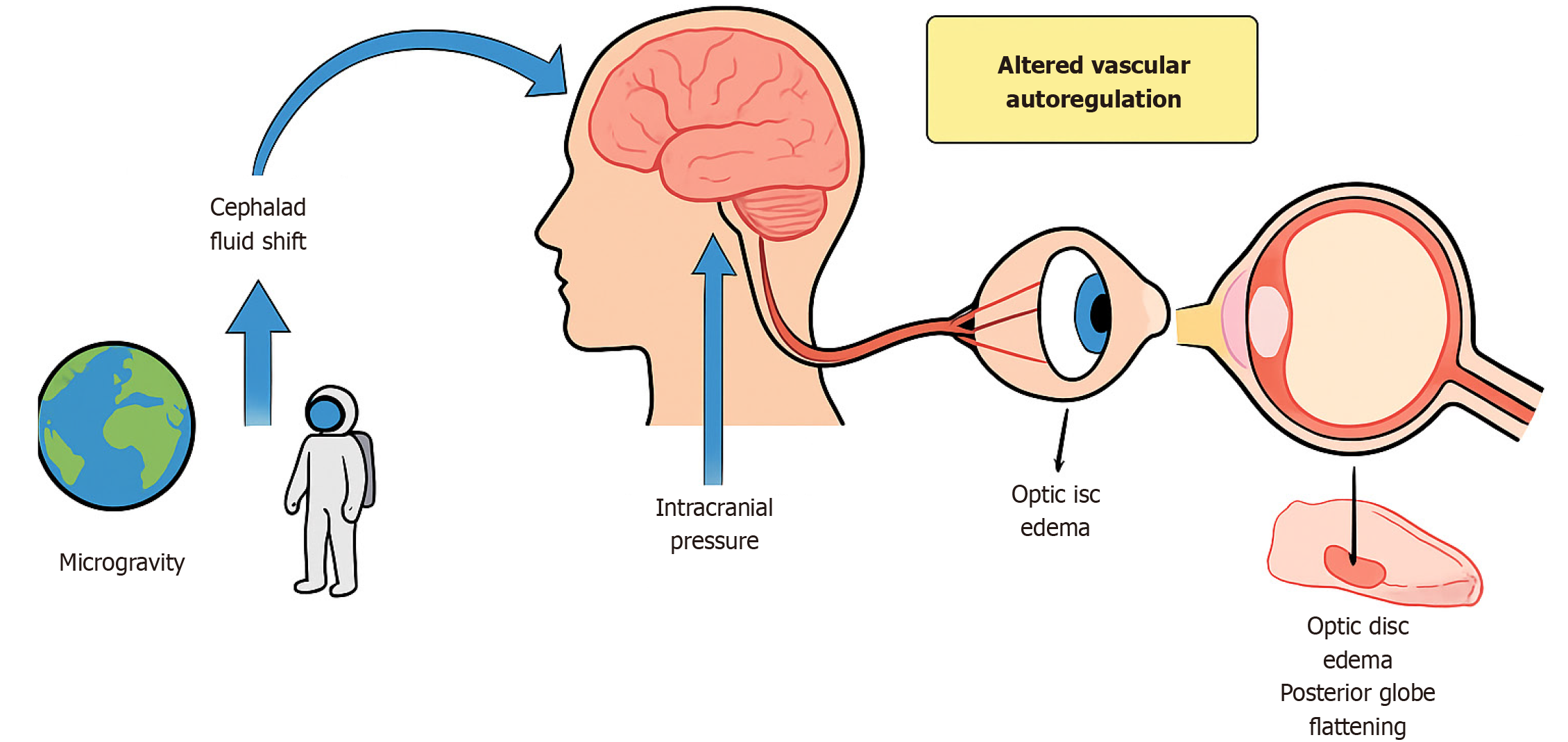

The prevailing hypothesis attributes SANS to cephalad fluid shifts under microgravity, leading to venous congestion and altered cerebrospinal fluid dynamics around the optic nerve. This cephalad shift is believed to result in chronically elevated intracranial pressure or altered intracranial pressure gradients, subsequently affecting the optic nerve and surrounding structures[1,4]. Yet, the pathophysiology is not fully explained by intracranial pressure changes alone, and ongoing work implicates venous outflow obstruction, impaired glymphatic clearance, and metabolic vulnerabilities (Figure 1).

In addition to pressure-related mechanisms, vascular factors play a contributory role. Microgravity-induced venous congestion and impaired cerebral and ocular venous outflow may disrupt autoregulation at the optic nerve head, thereby exacerbating optic disc edema and choroidal changes (Figure 2)[5,6]. Structural ocular alterations, including posterior globe flattening and optic nerve sheath distension, have been consistently demonstrated using optical coherence tomography (OCT) and magnetic resonance imaging. Individual susceptibility factors, such as genetic predisposition, one-carbon metabolism abnormalities (folate and vitamin B12 deficiencies), and anatomical variations of the optic nerve sheath, may further modulate SANS risk[6,7]. Beyond SANS, astronauts face a spectrum of ocular issues: Dry eye disease, ocular trauma from regolith or spacecraft particulates, opportunistic infections in the setting of immune dysregulation[8-11], while prolonged exposure to cosmic radiation accelerates cataract formation and may contribute to retinal microangiopathy (Figure 3)[12].

The implications of compromised ocular health extend beyond individual well-being and may directly impact mission safety and operational performance. As international space agencies plan prolonged missions, including lunar habitation and Mars exploration, addressing SANS becomes increasingly critical[13]. Ongoing research focuses on early detection using advanced imaging modalities, pharmacological interventions, and mechanical countermeasures such as lower body negative pressure. Preliminary lower body negative pressure studies have demonstrated partial mitigation of optic disc edema and choroidal thickening in small astronaut cohorts, although large-scale controlled trials remain lacking[14,15].

Understanding SANS is essential not only for astronaut safety but also for advancing terrestrial neuro-ophthalmology. Insights gained from spaceflight research may improve understanding of Earth-based conditions such as idiopathic intracranial hypertension and other disorders involving altered cerebrospinal fluid dynamics. There is a growing need for international consensus on SANS diagnostic criteria and standardized minimal datasets to harmonize research findings and facilitate meaningful comparisons across missions.

We conducted a structured literature review to evaluate ocular health in space, with emphasis on SANS and related conditions. Databases searched included PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science from database inception through August 2025, ensuring inclusion of the most recent evidence.

Search terms included “Spaceflight-Associated Neuro-ocular Syndrome”, “SANS”, “ocular changes AND space”, “microgravity AND eye”, “intracranial pressure AND spaceflight”, “ophthalmology AND space medicine”, and “choroidal folds AND space”. Boolean operators (AND/OR) were used to optimize search sensitivity and specificity. Manual searches of reference lists and citation tracking of key review articles were additionally performed to identify relevant studies not captured in the initial database search.

Inclusion criteria comprised peer-reviewed original articles, narrative reviews, and systematic reviews or meta-analyses published, focusing on human subjects, particularly astronauts, and addressing the pathophysiology, clinical manifestations, diagnosis, imaging findings, or management of ocular changes associated with spaceflight. Exclusion criteria included non-English publications, studies limited exclusively to terrestrial ophthalmic conditions without relevance to spaceflight, non-peer-reviewed literature such as opinion pieces or editorials (unless providing authoritative consensus), and studies involving animal models.

This review is structured as a narrative review. While elements of systematic search were employed, the heterogeneity of spaceflight-related data and the small number of astronaut subjects preclude meta-analysis. Instead, findings were synthesized thematically into major domains: Epidemiology of SANS, mechanisms, diagnostic approaches, other ocular conditions, and countermeasure strategies.

Two independent reviewers screened all titles and abstracts for relevance. A full-text review was then conducted on studies deemed potentially eligible. Any disagreements were resolved by consensus or by consulting a third reviewer. From each included study, data were extracted on study design, population characteristics, interventions, outcomes, and principal findings. Particular emphasis was placed on identifying recurrent patterns across studies, such as prevalence rates, common structural changes, hypothesized mechanisms, and proposed countermeasures.

The methodological quality of each study was appraised using standardized tools. Quality assessment was performed using the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale for observational studies and the Cochrane risk of bias tool for randomized controlled trials. Narrative reviews were assessed for clarity, scope, and the strength of evidence cited.

A thematic synthesis approach was employed. Findings were grouped into major themes: Prevalence and epidemiology of SANS, its pathophysiology, diagnostic modalities, and countermeasure strategies. Qualitative and quantitative findings were integrated to provide a comprehensive overview while acknowledging inherent limitations such as small sample size and heterogeneous methodologies. These limitations were explicitly considered when interpreting results and formulating conclusions.

SANS is a consistently reported consequence of exposure to microgravity, particularly during long-duration missions. Epidemiological studies indicate that signs of SANS occur in approximately 29%-30% of astronauts after short-duration spaceflight and increase to 60%-70% following missions longer than six months aboard the International Space Station[16,17]. These changes may persist for months to years after return to Earth and have the potential to impair mission performance (Table 1)[14].

| Ref. | Mission duration | Sample size | SANS prevalence | Key ocular findings | Imaging used |

| Mader et al[16] | Long-duration ISS | n = 7 | Approximately 60% | ODE, globe flattening, choroidal folds | Fundus, MRI |

| Martin Paez et al[13] | Mixed missions | Review | 30%-70% | ODE, hyperopia | Multimodal |

| Macias et al[2] | Long-duration ISS | n = 8 | Approximately 62% | ONH edema, refractive shift | OCT, MRI |

| Ferguson et al[22] | 6-month ISS mission | n = 11 | Approximately 55% | Optic disc edema | OCT |

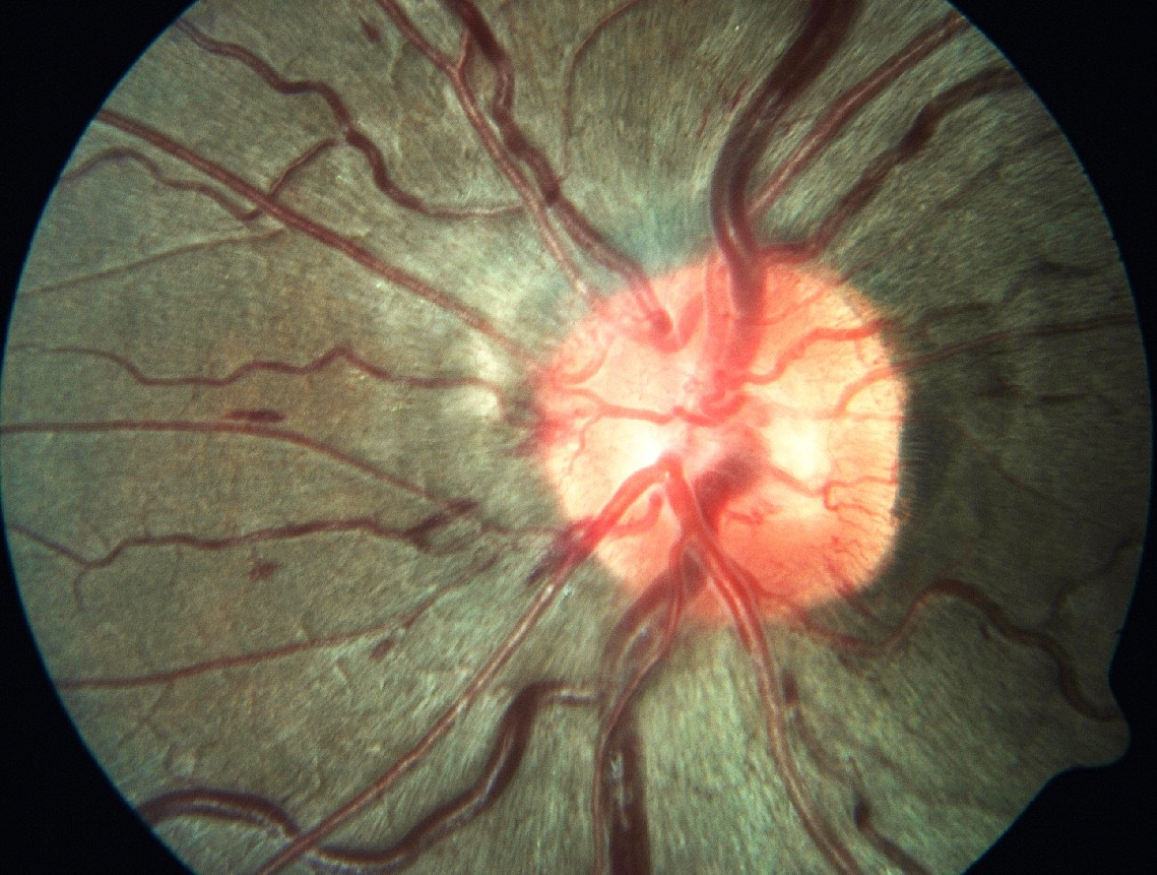

Optic disc edema is the hallmark feature of SANS and was first systematically described by Mader et al[16] in astronauts completing long-duration missions and later confirmed by other studies[17-19]. Subsequent investigations confirmed that optic disc edema can be chronic and may remain detectable long after spaceflight[16]. OCT has demonstrated thickening of the retinal nerve fiber layer, consistent with impaired axoplasmic flow and low-grade chronic optic nerve head swelling[2]. Notably, these changes often occur in the absence of markedly elevated intracranial pressure, distinguishing SANS from terrestrial papilledema[20,21].

A second defining feature is posterior globe flattening, which has been consistently observed on magnetic resonance imaging[17-19]. This deformation is thought to result from increased orbital cerebrospinal fluid pressure exerting chronic stress on the posterior sclera[16,17]. The flattening shortens axial length and contributes to the hyperopic shifts, most commonly ranging from + 0.5 diopters to + 1.5 diopters, frequently reported by astronauts[16,19].

Chorioretinal folds represent another important manifestation, thought to arise from venous outflow obstruction and mechanical stresses imposed by the crowded orbital compartment[22]. Similarly, changes in the retinal nerve fiber layer, including thickening and the presence of cotton wool spots, suggest localized axonal swelling, ischemia, and possibly oxidative injury[23,24].

Emerging evidence points to the role of individual susceptibility factors in determining which astronauts develop SANS. Microgravity causes fluid shifts, plasma volume loss, and cardiac atrophy, leading to cardiovascular deconditioning and orthostatic intolerance post-flight[25]. Genetic variations in one-carbon metabolism pathways, together with relative deficiencies in folate and vitamin B12, appear to increase vulnerability[26]. Nutritional supplementation has been pro

Different imaging modalities have been used to see the structural ocular changes in SANS (Table 2)[2,16,18,23]. The hypothesis that SANS represents a variant of venous overload choroidopathy has gained traction with recent studies[27]. Investigations using advanced ocular imaging have demonstrated that chronic venous congestion in the choroid and optic nerve head may provide a unifying explanation for optic disc edema, folds, and globe flattening[28]. This per

| Imaging modality | Structural changes | Ref. | Clinical significance |

| OCT | RNFL thickening, ODE | Macias et al[2]; Mader et al[16] | Early detection |

| MRI | Posterior globe flattening | Kramer et al[18] | Confirms ICP effects |

| Fundus photography | Choroidal folds | Mader et al[16] | Structural deformation |

| Ultrasound | ON sheath diameter increase | Fall et al[23] | Surrogate ICP marker |

Risk factors such as body habitus, fluid balance, and baseline ocular anatomy may modulate the degree of susceptibility. Astronauts with higher body mass and greater cephalad fluid shift appear to be more prone to developing ocular structural changes[29].

Although SANS has been the dominant focus of research, other ocular conditions have also been documented. Dry eye disease is among the most commonly reported complaints. The spacecraft environment, with its low humidity, increased carbon dioxide concentration, and limited tear evaporation, predisposes astronauts to ocular surface instability. A recent narrative review found that nearly all astronauts on long-duration missions reported some degree of ocular surface dryness[8]. Detailed studies have demonstrated alterations in tear film stability, meibomian gland function, and corneal epithelial integrity, collectively described as “space-associated dry eye syndrome”[9].

Another concern is the risk of ocular trauma. Particulate matter, either from spacecraft interiors or from lunar and Martian regolith, poses a direct hazard to the corneal surface. Laboratory simulations have shown that lunar dust is highly abrasive, raising concerns about its potential to cause lasting corneal injury during future exploration missions[10].

Ocular infections have also been described. Spaceflight is known to impair immune responses, leading to reactivation of latent viral infections and increased vulnerability to bacterial and fungal keratitis[11]. While severe infectious keratitis remains rare, its occurrence in the confined and resource-limited environment of space would represent a major oper

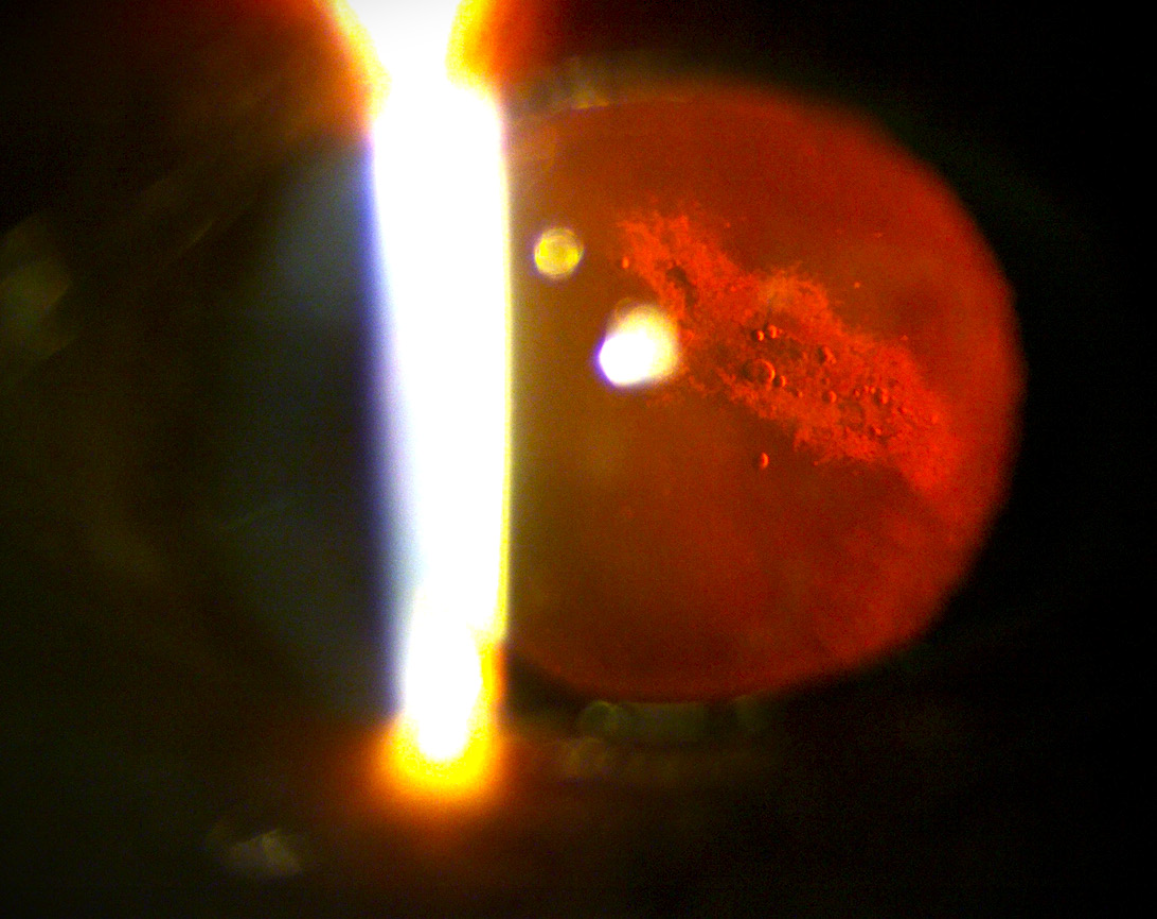

Radiation exposure during spaceflight adds long-term risk. Prolonged exposure to cosmic radiation accelerates cataract formation and may also contribute to retinal microangiopathy[12]. The cumulative risk is expected to be greater for astronauts on missions beyond low Earth orbit, such as lunar or Martian expeditions[12].

The findings of this review highlight that ocular health is not a peripheral issue in human spaceflight but a central determinant of astronaut safety and mission success. The prevalence of SANS, with estimates approaching 30% in short-duration missions and up to 60% in long-duration expeditions, emphasizes the scale of the challenge[13,22,30]. Even subtle changes in visual function can affect the precision and safety of tasks such as orbital piloting, robotic manipulation, and extravehicular activities[3,30]. Ocular trauma, foreign body exposure, and inflammatory conditions add further com

Efforts to detect and monitor ocular changes in flight have evolved considerably. Standard measures such as visual acuity and Amsler grid testing are supplemented with direct ophthalmoscopy and OCT[30,31]. Ultrasound-based measurement of the optic nerve sheath diameter has been especially valuable in the microgravity environment[23,32]. Post-flight assessments with magnetic resonance imaging and, in select cases, lumbar puncture have provided further insight into intracranial dynamics[17].

Emerging technologies now promise more autonomous and precise diagnostics. Advances in OCT angiography and deep learning algorithms allow automated detection of subtle retinal changes, offering objective quantification of optic disc edema and microvascular abnormalities[24,30,31]. Artificial intelligence-assisted OCT analysis has demonstrated high accuracy in detecting early SANS changes, while tele-ophthalmology platforms are being designed for remote monitoring during exploration missions[3,24]. Commercial initiatives have also begun testing wearable ocular sensors and portable imaging systems that could provide real-time data to ground control and, eventually, enable entirely auto

The search for effective countermeasures has been equally dynamic. Approaches that target the fundamental problem of fluid redistribution, such as lower body negative pressure devices, venous thigh cuffs, and impedance threshold breathing systems, have shown promise in reducing cephalad venous congestion[14,28,34,35]. Simulated artificial gravity through short-radius centrifugation has also been explored as a systemic countermeasure to both ocular and systemic effects of microgravity[25,35].

Nutritional strategies, including supplementation with folate and vitamin B12, aim to mitigate the influence of genetic predispositions in one-carbon metabolism[6,7,26,36]. Other avenues focus on pharmacological innovation and nano

A persistent challenge in this field is the lack of standardized definitions and diagnostic criteria[3,29]. Different space agencies and research groups have historically used varied terminology for overlapping ocular findings. This has complicated meta-analysis and hindered the establishment of universal countermeasure protocols. Calls have been made for a harmonized taxonomy and minimum dataset that would include OCT, OCT angiography, and standard automated perimetry across all agencies[13,31]. Establishing consistent nomenclature and agreed-upon endpoints will be vital as the field transitions from description to intervention.

Looking forward, several directions are clear. First, biomarkers of susceptibility, both systemic and ocular, are needed to identify at-risk individuals before flight[6,7,26,36]. Second, integrating artificial intelligence-driven imaging, nano

SANS poses a substantial and multifaceted risk to astronauts’ visual health, especially during extended missions. Current evidence suggests a complex interaction between cephalad fluid shifts, altered cerebrospinal fluid dynamics, venous congestion, and individual susceptibility factors. While advancements in imaging have improved early detection, comprehensive clinical trials evaluating preventive and therapeutic countermeasures are still lacking. Establishing standardized diagnostic criteria and minimal datasets through international collaboration is crucial for advancing research and safeguarding vision during future deep-space exploration.

| 1. | Ong J, Tarver W, Brunstetter T, Mader TH, Gibson CR, Mason SS, Lee A. Spaceflight associated neuro-ocular syndrome: proposed pathogenesis, terrestrial analogues, and emerging countermeasures. Br J Ophthalmol. 2023;107:895-900. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 15.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Macias BR, Ferguson CR, Patel N, Gibson C, Samuels BC, Laurie SS, Lee SMC, Ploutz-Snyder R, Kramer L, Mader TH, Brunstetter T, Alferova IV, Hargens AR, Ebert DJ, Dulchavsky SA, Stenger MB. Changes in the Optic Nerve Head and Choroid Over 1 Year of Spaceflight. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2021;139:663-667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Barratt MR, Baker ES, Pool SL. Principles of Clinical Medicine for Space Flight. New York: Springer, 2019. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 4. | Rodrigues GA, Russomano T, Santos Oliveira E. Understanding the relationship between intracranial pressure and spaceflight associated neuro-ocular syndrome (SANS): a systematic review. NPJ Microgravity. 2025;11:22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Rosenberg MJ, Coker MA, Taylor JA, Yazdani M, Matheus MG, Blouin CK, Al Kasab S, Collins HR, Roberts DR. Comparison of Dural Venous Sinus Volumes Before and After Flight in Astronauts With and Without Spaceflight-Associated Neuro-Ocular Syndrome. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2131465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Zwart SR, Gregory JF, Zeisel SH, Gibson CR, Mader TH, Kinchen JM, Ueland PM, Ploutz-Snyder R, Heer MA, Smith SM. Genotype, B-vitamin status, and androgens affect spaceflight-induced ophthalmic changes. FASEB J. 2016;30:141-148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Zwart SR, Gibson CR, Mader TH, Ericson K, Ploutz-Snyder R, Heer M, Smith SM. Vision changes after spaceflight are related to alterations in folate- and vitamin B-12-dependent one-carbon metabolism. J Nutr. 2012;142:427-431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 71] [Article Influence: 5.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ax T, Ganse B, Fries FN, Szentmáry N, de Paiva CS, March de Ribot F, Jensen SO, Seitz B, Millar TJ. Dry eye disease in astronauts: a narrative review. Front Physiol. 2023;14:1281327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ong J, Mader T, Gibson CR, Suh A, Panzo N, Memon H, Lee R, Soares B, Waisberg E, Sampige R, Nguyen T, Kadipasaoglu C, Guo Y, Vineyard K, Masalkhi M, Osteicoechea D, Vizzeri G, Chévez-Barrios P, Berdahl J, Barker DC, Schmitt HH, Lee AG. The ocular surface during spaceflight: Post-mission symptom report, extraterrestrial risks, and in-flight therapeutics. Life Sci Space Res (Amst). 2025;46:169-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Shah J, Ong J, Lee R, Suh A, Waisberg E, Gibson CR, Berdahl J, Mader TH. Risk of Permanent Corneal Injury in Microgravity: Spaceflight-Associated Hazards, Challenges to Vision Restoration, and Role of Biotechnology in Long-Term Planetary Missions. Life (Basel). 2025;15:602. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Crucian BE, Choukèr A, Simpson RJ, Mehta S, Marshall G, Smith SM, Zwart SR, Heer M, Ponomarev S, Whitmire A, Frippiat JP, Douglas GL, Lorenzi H, Buchheim JI, Makedonas G, Ginsburg GS, Ott CM, Pierson DL, Krieger SS, Baecker N, Sams C. Immune System Dysregulation During Spaceflight: Potential Countermeasures for Deep Space Exploration Missions. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1437. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 253] [Article Influence: 31.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Waisberg E, Ong J, Paladugu P, Kamran SA, Zaman N, Tavakkoli A, Lee AG. Radiation-induced ophthalmic risks of long duration spaceflight: Current investigations and interventions. Eur J Ophthalmol. 2024;34:1337-1345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Martin Paez Y, Mudie LI, Subramanian PS. Spaceflight Associated Neuro-Ocular Syndrome (SANS): A Systematic Review and Future Directions. Eye Brain. 2020;12:105-117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Harris KM, Petersen LG, Weber T. Reviving lower body negative pressure as a countermeasure to prevent pathological vascular and ocular changes in microgravity. NPJ Microgravity. 2020;6:38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hall EA, Whittle RS, Diaz-Artiles A. Ocular perfusion pressure is not reduced in response to lower body negative pressure. NPJ Microgravity. 2024;10:67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Mader TH, Gibson CR, Pass AF, Kramer LA, Lee AG, Fogarty J, Tarver WJ, Dervay JP, Hamilton DR, Sargsyan A, Phillips JL, Tran D, Lipsky W, Choi J, Stern C, Kuyumjian R, Polk JD. Optic disc edema, globe flattening, choroidal folds, and hyperopic shifts observed in astronauts after long-duration space flight. Ophthalmology. 2011;118:2058-2069. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 420] [Cited by in RCA: 455] [Article Influence: 30.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Roberts DR, Albrecht MH, Collins HR, Asemani D, Chatterjee AR, Spampinato MV, Zhu X, Chimowitz MI, Antonucci MU. Effects of Spaceflight on Astronaut Brain Structure as Indicated on MRI. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1746-1753. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 181] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 23.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kramer LA, Hasan KM, Stenger MB, Sargsyan A, Laurie SS, Otto C, Ploutz-Snyder RJ, Marshall-Goebel K, Riascos RF, Macias BR. Intracranial Effects of Microgravity: A Prospective Longitudinal MRI Study. Radiology. 2020;295:640-648. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 12.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Nguyen T, Ong J, Brunstetter T, Gibson CR, Macias BR, Laurie S, Mader T, Hargens A, Buckey JC, Lan M, Wostyn P, Kadipasaoglu C, Smith SM, Zwart SR, Frankfort BJ, Aman S, Scott JM, Waisberg E, Masalkhi M, Lee AG. Spaceflight Associated Neuro-ocular Syndrome (SANS) and its countermeasures. Prog Retin Eye Res. 2025;106:101340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Venegas JM. Spaceflight-associated neuro-ocular syndrome: potential etiologies and connections to the glymphatic system. J Neurophysiol. 2024;131:785-788. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Buckey JC, Phillips SD, Anderson AP, Chepko AB, Archambault-Leger V, Gui J, Fellows AM. Microgravity-induced ocular changes are related to body weight. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2018;315:R496-R499. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Ferguson CR, Pardon LP, Laurie SS, Young MH, Gibson CR, Brunstetter TJ, Tarver WJ, Mason SS, Sibony PA, Macias BR. Incidence and Progression of Chorioretinal Folds During Long-Duration Spaceflight. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2023;141:168-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Fall DA, Lee AG, Bershad EM, Kramer LA, Mader TH, Clark JB, Hirzallah MI. Optic nerve sheath diameter and spaceflight: defining shortcomings and future directions. NPJ Microgravity. 2022;8:42. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Huang AS, Jalili J, Walker E, Weinreb RN, Laurie SS, Macias BR, Christopher M. Artificial Intelligence Deep Learning Models to Predict Spaceflight Associated Neuro-Ocular Syndrome. Am J Ophthalmol. 2025;278:115-123. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 25. | Guo M, Guo G, Ji X. Genetic polymorphisms associated with heart failure: A literature review. J Int Med Res. 2016;44:15-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Smith SM, Zwart SR. Spaceflight-related ocular changes: the potential role of genetics, and the potential of B vitamins as a countermeasure. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2018;21:481-488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Mampre D, Spaide R, Mason S, Van Baalen M, Gibson CR, Mader TH, Wostyn P, Briggs J, Brown D, Lee AG, Patel N, Tarver W, Brunstetter T. Spaceflight Associated Neuro-Ocular Syndrome as a Potential Variant of Venous Overload Choroidopathy. Aerosp Med Hum Perform. 2025;96:496-508. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Hooper SB, Te Pas AB, Blank DA, Polglase GR. The physiology of delayed umbilical cord clamping at birth: let's not add to the confusion. J Physiol. 2022;600:3625-3626. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Mehare A, Chakole S, Wandile B. Navigating the Unknown: A Comprehensive Review of Spaceflight-Associated Neuro-Ocular Syndrome. Cureus. 2024;16:e53380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Kanzow AF, Schmidt D, Kanzow P. Scoring Single-Response Multiple-Choice Items: Scoping Review and Comparison of Different Scoring Methods. JMIR Med Educ. 2023;9:e44084. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Lee AG, Mader TH, Gibson CR, Tarver W, Rabiei P, Riascos RF, Galdamez LA, Brunstetter T. Spaceflight associated neuro-ocular syndrome (SANS) and the neuro-ophthalmologic effects of microgravity: a review and an update. NPJ Microgravity. 2020;6:7. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 30.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Meer EA, Church LE, Johnson BA, Rohde J, Sinclair AJ, Mollan SP, Petersen L, Polk JD, Sawyer AJ. Non invasive monitoring for spaceflight associated neuro ocular syndrome: responding to a need for In flight methodologies. NPJ Microgravity. 2025;11:61. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Stern C, Yücel YH, Zu Eulenburg P, Pavy-Le Traon A, Petersen LG. Eye-brain axis in microgravity and its implications for Spaceflight Associated Neuro-ocular Syndrome. NPJ Microgravity. 2023;9:56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Watkins W, Hargens AR, Seidl S, Clary EM, Macias BR. Lower-body negative pressure decreases noninvasively measured intracranial pressure and internal jugular vein cross-sectional area during head-down tilt. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2017;123:260-266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Marshall-Goebel K, Macias BR, Laurie SS, Lee SMC, Ebert DJ, Kemp DT, Miller A, Greenwald SH, Martin DS, Young M, Hargens AR, Levine BD, Stenger MB. Mechanical countermeasures to headward fluid shifts. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2021;130:1766-1777. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Lane HW, Bourland C, Barrett A, Heer M, Smith SM. The role of nutritional research in the success of human space flight. Adv Nutr. 2013;4: 521-523. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/