Published online Dec 26, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i36.116656

Revised: December 3, 2025

Accepted: December 12, 2025

Published online: December 26, 2025

Processing time: 38 Days and 15.7 Hours

Psoriasis is often first recognized by patients through online image searches. However, search engine algorithms influenced by geographic location may still produce results that predominantly feature lighter skin tones, regardless of the region’s majority skin type. This underrepresentation may limit recognition and delay care for people of color.

To examine whether search algorithms tailor region-specific results in terms of skin color for psoriasis imagery.

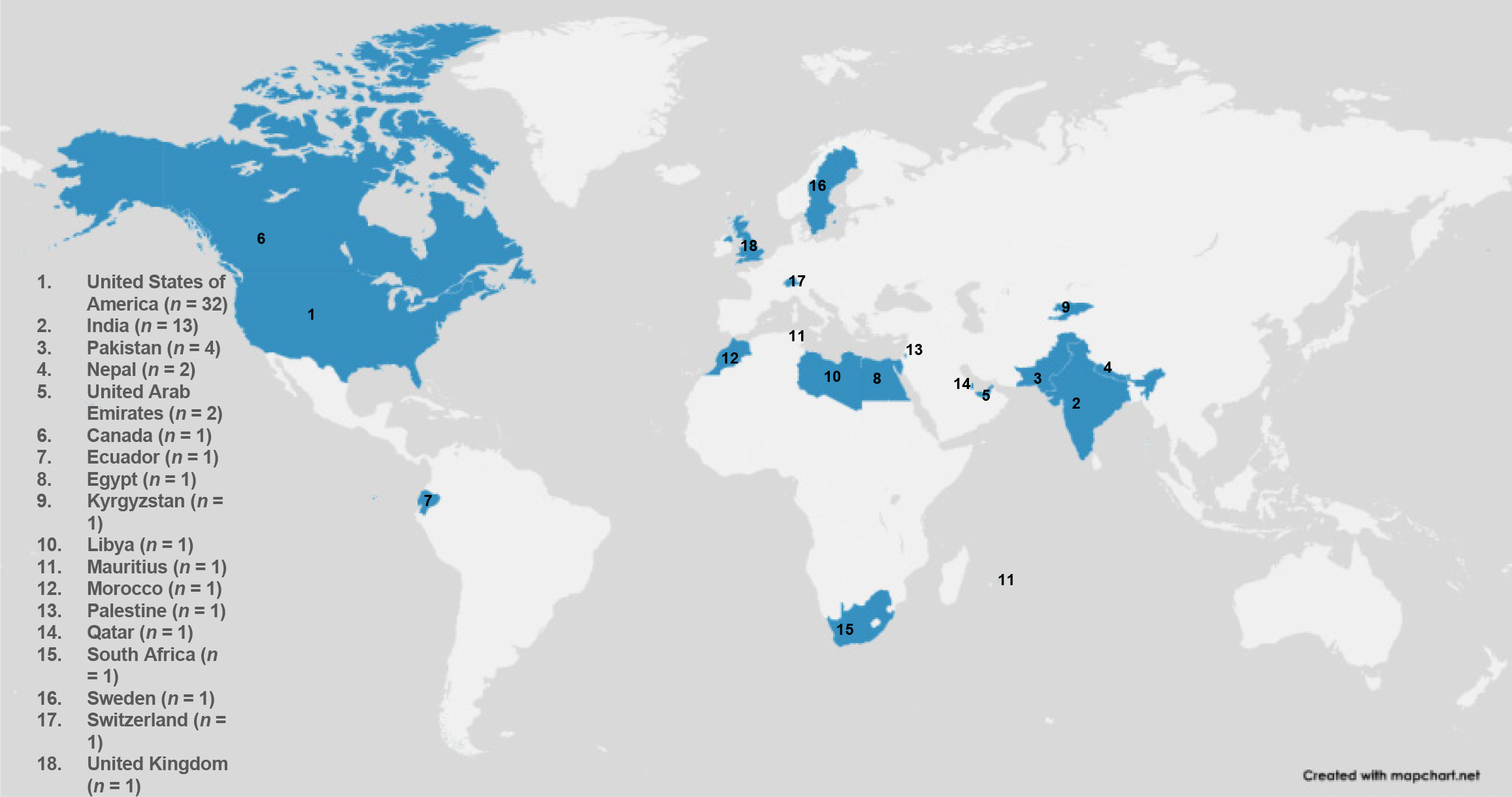

This observational study recruited 66 participants from 18 countries who con

Results showed a global bias toward lighter skin tones, with 94% of participants identifying light skin predominance in the first row and minimal representation of medium or darker skin tones in subsequent results, verified via χ2 analysis. Participants who observed darker or mixed skin tones typically found them further down their results.

There remains a significant gap in global representation of psoriasis imagery. This paper deepens the current understanding of bias in online media and pushes for further exploration of more inclusive dermatologic imagery.

Core Tip: In this global observational study, online psoriasis image search results across major web browsers were systematically analyzed to assess the representation of skin tone. Lighter skin tones overwhelmingly predominated early search results, while darker skin tones were consistently ranked lower in visibility, limiting early exposure for patients of color. These findings reinforce a lack of diverse dermatologic imagery worldwide and underscore the need for more equitable medical resources.

- Citation: Sandhu A, Ailani S, Padte S, Mehta P, Deo N, Surani S, Kashyap R. Skin tone bias in online psoriasis imagery: Insights from an international study. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(36): 116656

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i36/116656.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i36.116656

Psoriasis is one of the most common dermatologic conditions, affecting approximately 125 million individuals worldwide[1]. Delayed management of this disease can lead to serious inflammatory complications such as psoriatic arthritis and cardio-metabolic disease[2-4]. With increasing reliance on digital health information, patients frequently use the internet before seeking medical attention. Online visual references are a common first-line resource for patients to identify their condition and seek professional consultation. While this may improve patient awareness, it is only effective if the available imagery reflects the diversity of the global population. Individuals with skin of color are often underrepresented in medical literature, making it difficult to visually match their lesions to reference images[5-7]. This lack of representation can lead to delayed diagnoses, treatment, and worse health outcomes[8-10]. This study aimed to evaluate whether geographic location influences the underrepresentation of diverse skin tones in online dermatologic conditions.

Search algorithms are tailored to a user’s internet protocol address, a numerical label assigned to each device connected to the internet, which allows engines to approximate geographic location to deliver relevant results[11,12]. In theory, this should allow for online dermatologic media to reflect the representative skin tones of the query’s region. Prior research has shown that online medical imagery often skews toward lighter skin tones. However, these findings are limited to the national contexts examined in each study. Global trends have not been analyzed, leaving a gap in understanding how such biases may delay diagnosis and management.

To address this, we developed the global Project for Revealing Online Bias and Exploration (PROBE), the first international study to examine disparities in online psoriasis image representation worldwide. Through a comprehensive survey, PROBE aimed to investigate how search engine algorithms, particularly those influenced by geographic location, affect the diversity of psoriasis image results delivered to users.

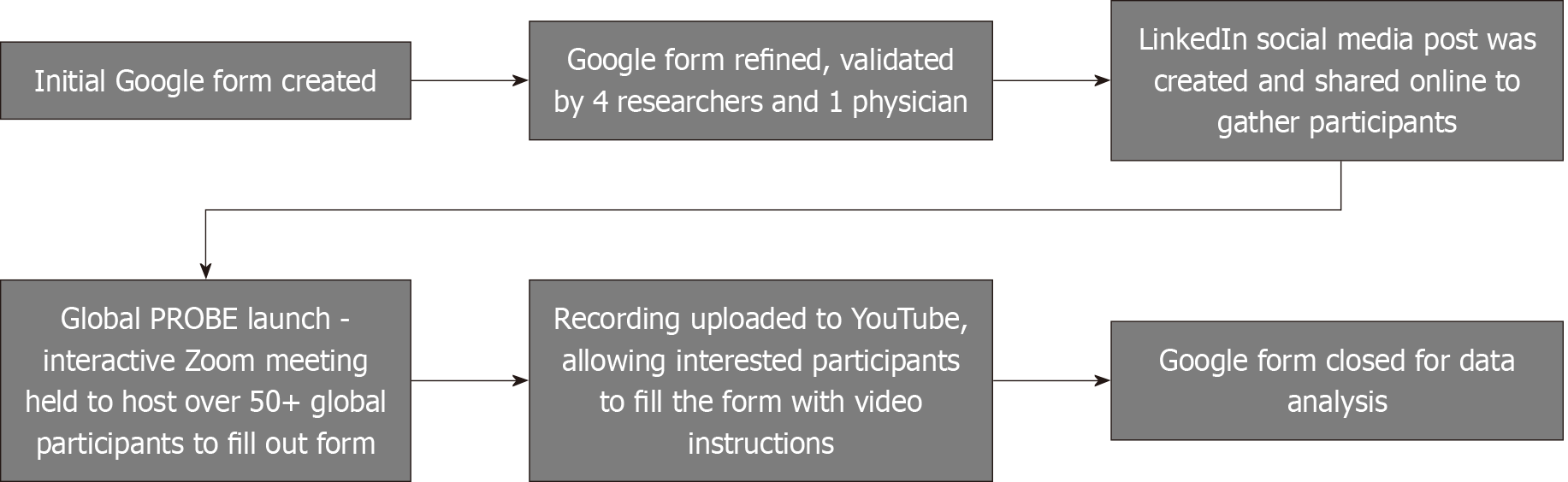

In this observational study, participants were recruited internationally to join an interactive online video conferencing session on the Zoom videoconferencing platform led by the primary investigators. The meeting link was posted on the professional social networking platform LinkedIn via a well-established professional network. The primary authors hosted the session, facilitated the study, and answered relevant questions. A link to a Google form was sent to par

Basic demographic information, such as users’ age groups, current country of residence, and city, was logged before conducting the investigation. All participants were informed of the nature of the study and provided with voluntary participation. This study is considered Institutional Review Board exempt because no patient-identifying health information was sought or recorded.

Each participant was asked to input the term “psoriasis” into their image browser of choice. Safe image blurring was disabled to ensure uniformity. The authors requested that participants adjust their zoom levels to ensure that at least 5 images were visible on screen. To improve consistency and accuracy in skin tone categorization, a reference image depicting Fitzpatrick skin types II (light), IV (medium), and VI (dark) was embedded directly in the Google form. Participants were instructed to refer to this image while evaluating each search results. All images, both clinical and non-clinical, were included in the analysis to provide a holistic assessment of what users might encounter during a typical image search.

Initially, participants were asked to note the number of dark or medium skin-toned images in the first row. This row was analyzed as it represents the highest-ranked images returned by the search engine. Afterward, participants were asked to identify the predominant skin tone in each of the three rows to assess how skin tone representation varied by image ranking. This was defined as a majority of ≥ 3 images per row showing a given skin tone. Rows with equal representation of skin tones were categorized as balanced, indicating no predominant skin tone. For images where the background, lighting, or resolution made it difficult to determine pigmentation, participants were instructed to exclude these images from their assessment and move to the next clearly visible one in the row. Additional verbal guidance was provided during the Zoom session to help standardize interpretation.

A recording of the session was uploaded to YouTube for future participation. The video remained on the YouTube channel while the Google form was closed after two months for data analysis. To further evaluate the influence of IP-based geolocation, the primary author conducted controlled, identical psoriasis image searches using VPNs set to multiple countries across different continents.

Following data collection, a χ2 test was performed to assess deviations from expected outcomes (equal representation of color). When small, expected frequencies were observed, Fisher’s exact test was applied. Effect sizes were quantified using Cramér’s V and are reported alongside P-values. The form questions were externally validated by a group of four researchers and one physician. The design process is highlighted in Figure 1.

A total of 66 participants from 18 countries and 5 continents took part in the study. Among these, 46 attended live, whilst 19 filled out the form after the video upload. One participant completed the survey before the scheduled meeting but followed the same protocol and was therefore included in the analysis. Baseline characteristics of global PROBE par

| Category | Subgroup | n (%) |

| Gender | Male | 32 (48.5) |

| Female | 34 (51.5) | |

| Age (years) | 18-21 | 7 (10.6) |

| 21-25 | 15 (22.7) | |

| 25-30 | 27 (40.9) | |

| 30-40 | 11 (16.7) | |

| 40-55 | 5 (7.6) | |

| > 55 | 1 (1.5) | |

| Country | United States | 21 (31.8) |

| India | 9 (13.6) | |

| Pakistan | 3 (4.5) | |

| Other (combined) | 33 (50.0) | |

| Ethnicity | South Asian | 43 (65.2) |

| Black (United States and Africa) | 13 (19.7) | |

| White Caucasian | 3 (4.5) | |

| Other | 7 (10.6) | |

| Institution | Private academic | 26 (39.4) |

| Government academic | 15 (22.7) | |

| Private non-academic | 8 (12.1) | |

| Other | 17 (25.8) | |

| Career stage | Medical student | 22 (33.3) |

| Faculty/practitioner | 11 (16.7) | |

| Resident/fellow | 9 (13.6) | |

| Researcher | 9 (13.6) | |

| Other | 15 (22.8) |

Most participants were female (n = 34, 51.5%), and 63.6% were of South Asian origin (India, Pakistan, Nepal, Bangladesh, etc.), resulting in a less homogeneous representation across the sample. Majority were either medical students, residents, fellows, or practicing providers (n = 42, 67%). Ages ranged from 21 years to 55 years, with the most representation between 25 years and 30 years old (n = 27, 41%). Google Chrome was the most popular browser (n = 48, 72.7%), followed by Safari (n = 13, 19.7%). These results are shown in Table 1.

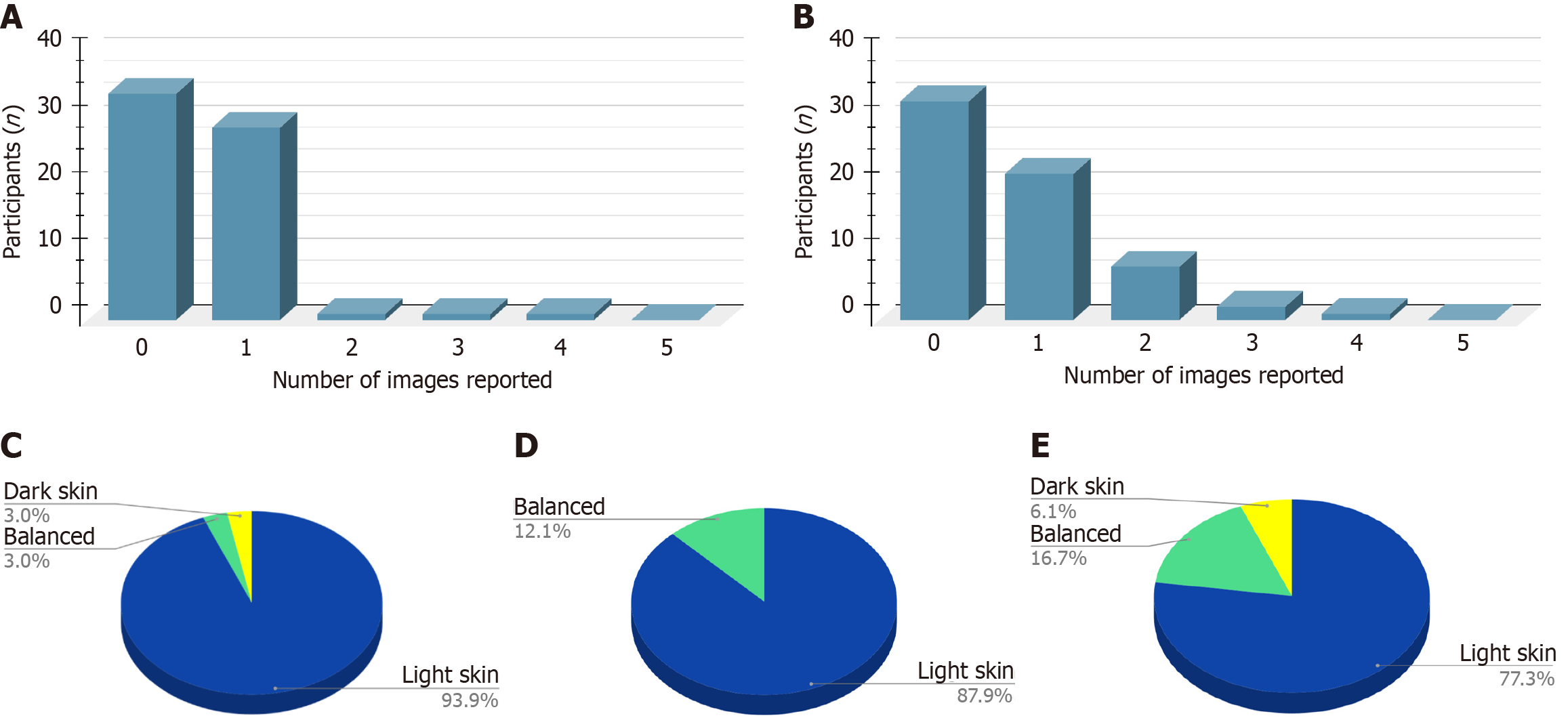

When asking participants how many images in the first row depicted dark skin, 95.4% (n = 63) reported either 0 or 1. In regards to medium-toned skin, 83.3% of participants reported either 0 (n = 34) or 1 (n = 29). Figure 3A and B details these observations.

When asked to report the predominant skin tone in the first row, 94% (n = 62) reported light skin predominance, dark and balanced representation were each reported by 2 participants (χ2 = 109.091, P < 0.0001). For the second row of images, 87% (n = 58) reported light skin predominance, 8 reported balanced representation, and 0 reported dark skin (χ2 = 89.818, P < 0.0001). For the third row of images, 77.3% (n = 51) reported light skin predominance, 16.7% (n = 11) reported balanced representation, and 6.1 % (n = 4) reported dark skin (χ2 = 58.455, P < 0.0001). All significant χ2 comparisons demonstrated large effect sizes (Cramér’s V = 0.67-0.91). A further subgroup analysis by professional experience, analyzed using Fisher’s exact test due to small cell sizes, demonstrated no statistically significant differences in predominant skin tone classification across all three rows. Following controlled identical searches conducted using VPNs set to multiple countries across different continents, lighter skin tones remained overwhelmingly predominant, indicating minimal regional modulation of image search outputs.

Among the participants, four individuals reported seeing a predominance of darker skin tones, specifically from Morocco (Fez), Kyrgyzstan (Bishkek), India (Pune), and the United States (Seattle). All four of them found this dark skin predominance in row 3 of the images, and 2/4 found it in row 1. Three out of the four (75%) indicated that row 2 featured a more balanced representation of skin tones. This is highlighted in Figure 3C-E.

This study explores a possible global bias toward lighter skin tones in online psoriasis image searches, raising concerns about the accessibility of relevant visual references for individuals with darker skin tones. Our findings show that lighter skin is overrepresented in search results, regardless of the user’s geographic region or population demographics. Participants across diverse locations, including South Africa and India, frequently reported difficulty finding images of darker skin tones in their search results. When darker or more balanced skin tone predominance was observed, it was consistently relegated to lower-ranking rows of search results, limiting early visibility.

One possible explanation for these findings is the dominance of globally trained algorithms that rely heavily on non-diverse image databases, which may prioritize lighter skin tones regardless of regional context. These algorithms may not adequately incorporate local data, leading to a mismatch between search results and the populations viewing them. Alternatively, there may be an overall shortage of publicly available images of psoriasis on darker skin. Dermatologists in resource-limited settings may not have the clinical opportunities to upload clinical imagery in comparison to resource-abundant countries such as the United States. Exploring these mechanisms is essential to understanding the root causes of this disparity.

The results of this study add to the current biases in online dermatology image searches. Prior studies have shown disparities in image search outcomes for dermatological conditions[13,14], but this study takes this idea to a larger scale. Previous research has been limited to country-specific reviews, leaving gaps in understanding the broader global context of image representation[15]. By including data from multiple nations, global trends in geographic and algorithmic variation are seen. This highlights a potential lack of resources for individuals of darker skin tones, as people may not be able to identify their lesions through online media correctly, leading to possible delays in care[16,17]. This study may inform future efforts for examining biases and promoting greater diversity in dermatological images across medical literature and online media[18-20]. Future studies may additionally examine disparities in image searches for other dermatologic conditions, a more patient-centered focus can be taken to assess the impact of this resource gap. This may improve access for both patients and clinicians to have the most accurate, representative information available[21].

The strength of this study lies in its innovative approach, being among the first global investigations to explore psoriasis-related media. This unique aspect allows for a more accurate and up-to-date understanding of the biases present in online search engines. Additionally, the method of instructing participants to use incognito mode and specific browser settings ensures the integrity of the data by minimizing external influences, such as prior search history and location-spoofing. This study was able to garner international support from participants from five continents. This geographic spread of participants adds methodological strength to understanding digital disparities in healthcare resources.

Several factors limit the generalizability of our findings. First, the sample size was relatively small, and participant distribution was not demographically or geographically homogeneous. With most participants being from either the United States or South Asia, other countries had limited representation. Many European countries only had 1 participant which skews the regional balance. Additionally, the reference images used to represent Fitzpatrick skin tones were not independently verified by board-certified dermatologists, which may limit the reliability of skin tone matching. The large presence of younger medical trainees further limits the analysis, as their interpretations of skin tones may differ compared to practicing dermatologists. Because each participant evaluated a unique, personalized set of image results, formal inter-rater reliability metrics were also not applicable. Finally, since data collection occurred live or asynchronously, adherence to study instructions could not be directly monitored. Despite this, all submitted responses were included. Future studies can enroll larger, more geographically balanced cohorts and use standardized image sets verified by dermatologists to strengthen skin tone classifications further.

In summary, this study reveals a global bias in online psoriasis images, with a strong preference for lighter skin tones across all regions. Darker or more balanced representations were typically found lower in participants’ queries, regardless of the country from which an individual was searching. This paper provides a framework for future investigation of digital technologies in dermatology and their effects on patient outcomes.

| 1. | Armstrong AW, Read C. Pathophysiology, Clinical Presentation, and Treatment of Psoriasis: A Review. JAMA. 2020;323:1945-1960. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 531] [Cited by in RCA: 1536] [Article Influence: 256.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Nair PA, Badri T. Psoriasis. 2023 Apr 3. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan-. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Toussirot E, Gallais-Sérézal I, Aubin F. The cardiometabolic conditions of psoriatic disease. Front Immunol. 2022;13:970371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Hu SC, Lan CE. Psoriasis and Cardiovascular Comorbidities: Focusing on Severe Vascular Events, Cardiovascular Risk Factors and Implications for Treatment. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18:2211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 15.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Kurtti A, Austin E, Jagdeo J. Representation of skin color in dermatology-related Google image searches. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:705-708. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 6. | Chen V, Akhtar S, Zheng C, Kumaresan V, Nouri K. Assessment of Changes in Diversity in Dermatology Clinical Trials Between 2010-2015 and 2015-2020: A Systematic Review. JAMA Dermatol. 2022;158:288-292. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Takeshita J, Chau J, Duffin KC, Goel N. Promoting Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion for Psoriatic Diseases. J Rheumatol. 2022;49:48-51. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Yadav G, Yeung J, Miller-Monthrope Y, Lakhani O, Drudge C, Craigie S, Mendell A, Park-Wyllie L. Unmet Need in People with Psoriasis and Skin of Color in Canada and the United States. Dermatol Ther (Heidelb). 2022;12:2401-2413. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Peterson H, Huang MY, Lee K, Kingston P, Yee D, Korouri E, Agüero R, Armstrong AW. Comorbidity Burden in Psoriasis Patients with Skin of Color. J Psoriasis Psoriatic Arthritis. 2024;9:16-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chatrath S, Bradley L, Kentosh J. Dermatologic conditions in skin of color compared to white patients: similarities, differences, and special considerations. Arch Dermatol Res. 2023;315:1089-1097. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Cooper C, Lorenc T, Schauberger U. What you see depends on where you sit: The effect of geographical location on web-searching for systematic reviews: A case study. Res Synth Methods. 2021;12:557-570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Halavais A. Search Engine Society. 2nd ed. Polity, 2017. |

| 13. | Fathy R, Lipoff JB. Lack of skin of color in Google image searches may reflect under-representation in all educational resources. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2022;86:e113-e114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Falotico JM, Lipner SR. Few skin of color images in Google image searches of nail conditions. Int J Dermatol. 2023;62:e153-e155. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Nasseri M, Sadur A, McCormick ET, Friedman A. The Representation of Skin Tones in Google Images of Skin Cancers. J Drugs Dermatol. 2024;23:e132-e133. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Serrano L, Ulschmid C, Szabo A, Roth G, Sokumbi O. Racial disparities of delay in diagnosis and dermatologic care for hidradenitis suppurativa. J Natl Med Assoc. 2022;114:613-616. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Narla S, Heath CR, Alexis A, Silverberg JI. Racial disparities in dermatology. Arch Dermatol Res. 2023;315:1215-1223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Rana A, Witt A, Jones H, Mwanthi M, Murray J, Zickuhr L. Representation of Skin Colors in Images of Patients With Lupus. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2022;74:1835-1841. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Bae C, Cheng M, Kraus CN, Desai S. Representation of Skin of Color in Rheumatology Educational Resources. J Rheumatol. 2022;49:419-423. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Yee D, Lee K, Huang MY, Kingston P, Korouri E, Peterson H, Armstrong AW. Assessing the Quality, Comprehensiveness, and Readability of Online Patient Health Resources About Psoriasis in Skin of Color. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2023;16:52-54. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Scott K, Poondru S, Jackson KL, Kundu RV. The need for greater skin of color training: perspectives from communities of color. Arch Dermatol Res. 2023;315:2441-2444. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/