Published online Dec 26, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i36.113778

Revised: October 24, 2025

Accepted: December 8, 2025

Published online: December 26, 2025

Processing time: 113 Days and 17.7 Hours

Fasciola hepatica (F. hepatica) (liver fluke) is a parasitic trematode that infects humans through the consumption of contaminated aquatic plants harboring the infective stage of the parasite. Despite being a neglected tropical disease, a World Health Organi

We report 4 cases with varied and unusual presentations. Case 1: A 41-year-old woman with an initial presumptive clinical diagnosis of liver malignancy. Case 2: A 34-year-old woman who presented with urticaria and eosinophilia, initially suspected to be vasculitis. Case 3: A 67-year-old man who presented with dys

Hepatic fascioliasis is frequently misdiagnosed due to its non-specific symptoms and limited diagnostic tools, especially in resource-limited settings. It is crucial to enhance awareness among healthcare professionals regarding its recognition and appropriate management. This case report aims to contribute to the growing body of literature on F. hepatica infection to facilitate timely diagnosis and empiric treatment with triclabendazole or nitazoxanide, as these are effective and reduce unnecessary interventions.

Core Tip: Hepatic fascioliasis remains a significant yet under-recognized cause of morbidity, particularly in endemic regions. Its variable presentations, prolonged clinical course, and limited clinician awareness—coupled with constrained access to serologic testing—often lead to misdiagnosis (e.g., as malignancy or bacterial abscess). This results in unnecessary costs and delayed treatment. A high index of clinical suspicion, a thorough inquiry about exposure and travel history, recognition of characteristic imaging findings, and correlation with eosinophilia are critical for a timely diagnosis. Early empiric treatment, which is simple and cost-effective, can prevent invasive procedures and reduce the patient burden.

- Citation: Mulate ST, Gesese BD, Nur AM, Mengistu HB, Annose RT, Berga AE, Ulfata AL. Hepatic fascioliasis: Emphasizing diagnostic difficulty and the need for high index of suspicion: Four case reports. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(36): 113778

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i36/113778.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i36.113778

Fasciola hepatica is a parasitic trematode and a significant cause of the snail-borne disease fascioliasis. While it primarily infects domestic ruminants like sheep and cattle, causing substantial economic losses, it has also emerged as an important neglected tropical disease in humans, who act as incidental hosts[1]. Globally, 180 million people are believed to be at risk of infection in more than 50 countries. It is endemic in many parts of the world including Central and South America, Asia, Africa and Middle East particularly in developing countries with poor sanitation and limited access to clean water sources[2,3].

The global distribution of fascioliasis is dependent on competent intermediate snail hosts. Fasciola hepatica (F. hepatica) is more common in temperate zones, while F. gigantica is found in tropical areas, including parts of Africa[4,5]. In Ethiopia, F. hepatica is the most prevalent liver fluke, typically found at higher altitudes, though mixed infections with F. gigantica can occur[6,7]. While animal fasciolasis is well-documented and highly prevalent in Ethiopia[8,9], data on human infection are more limited. Available studies indicate a significant disease burden, with prevalence among high-risk groups, such as school-aged children, ranging from 2.5%-9.8%[8].

Human infection is typically acquired by ingesting metacercariae on contaminated aquatic plants, such as watercress. Diagnosis can be challenging, relying on a combination of clinical suspicion, imaging, and diagnostic techniques like serology (e.g., antibody the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay) or stool examination[10].

Given its status as a neglected tropical disease and its potential for unusual clinical presentations, fascioliasis is often misdiagnosed. This highlights a critical need for enhanced awareness among healthcare professionals. This case report aims to contribute to the clinical literature on human F. hepatica infection to facilitate timely diagnosis and appropriate management, thereby helping to reduce the associated morbidity.

Case 1: A 41-year-old woman presented with dull aching right upper abdominal pain of 6 months duration.

Case 2: A 34-year-old female patient presented with urticaria for 1 month.

Case 3: A 67-year-old female patient from Addis Ababa presented with a 2-week history of dyspepsia.

Case 4: A 60-year-female presented with abdominal pain and vomiting of 2 weeks duration.

Case 1: She had nausea and intermittent vomiting of ingested matter associated with loss of appetite and fatigue of 6 months duration.

Case 2: She took different anti histamines for her presenting complaint but had poor response. She had new onset right side chest pain of 1 day duration with dyspepsia and difficulty of swallowing. On further inquiry, she had intermittent knee joint pain and flu like symptoms for the preceding few weeks.

Case 3: Associated with the above complaint she also has easy fatigability, headache, and high grade intermittent fever. She denied any right upper quadrant (RUQ) abdominal pain or vomiting.

Case 4: Associated with the above complaint she also has easy fatigability and loss of appetite. She had no history of jaundice, fever, anorexia or weight loss.

Cases 1 and 2: No pertinent history of hospitalization or known chronic illness.

Case 3: Associated with the above complaint she also has easy fatigability, headache, and high grade intermittent fever. She denied any RUQ abdominal pain or vomiting.

Case 4: Her past medical history was significant for well controlled bronchial asthma and remote cholecystectomy.

Case 1: There is no additional personal or family history of diabetes, high blood pressure, or cardiac conditions.

Case 2: The patient’s personal and family history is negative for heart disease, hypertension, and diabetes.

Case 3: No history of cardiovascular illness, high blood pressure, or diabetes is known in the patient or their family.

Case 4: Beyond the presenting condition, the patient reports no personal or familial instances of diabetes, hypertensive disease, or heart disorders.

Case 1: Physical examination revealed normal vital signs and a mild right upper quadrant tenderness. Abdominal palpation did not reveal liver or spleen enlargement.

Case 2: Physical finding was non-revealing on the first presentation for the urticaria but on the second presentation, she had tachypnea and tachycardia. Chest and cardiovascular examinations were unremarkable.

Case 3: The patient had normal vital signs. Abdominal examination revealed no significant findings.

Case 4: Physical exam was remarkable for right upper quadrant tenderness. Otherwise normal findings.

Case 1: Pertinent laboratory findings included leukocytosis with significant eosinophilia, accounting for 38% of the white cell population (absolute count 3990 cells/mL). Comprehensive metabolic panel assessing renal function, electrolytes, and liver enzymes was unremarkable. Serologic screening for blood-borne pathogens (hepatitis B, hepatitis C, syphilis, human immunodeficiency virus) returned negative results.

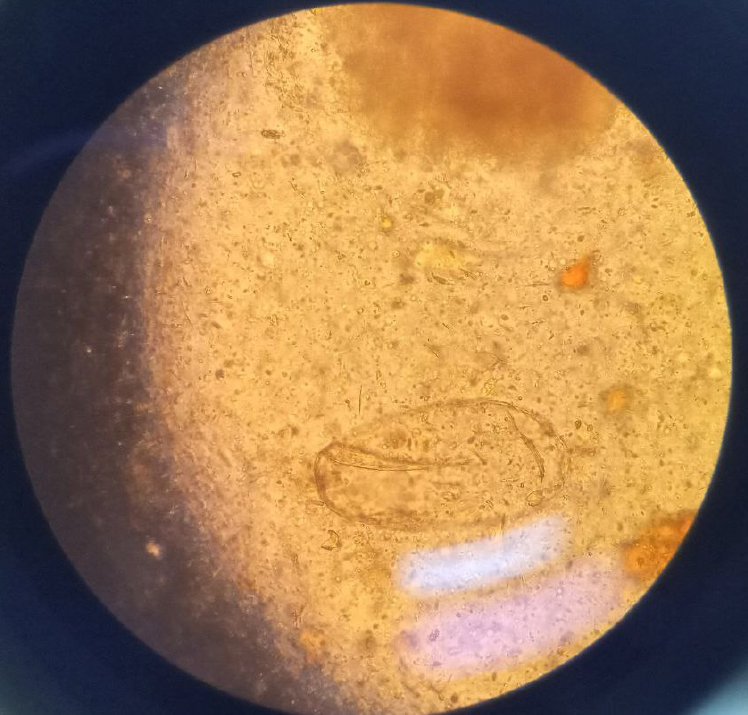

Case 2: Laboratory tests showed a white blood count of 10600 cells/mL (neutrophil count was 8480 cells/mL [80%]) eosinophil count was slightly elevated, 699 cells/mL (6.6%). Repeated complete blood count showed a white blood count of 6130 cells/mL with eosinophil count of 1240 cells/mL (20.2%). Further studies showed a normal serum Rheumatoid actor titer, complement 3 (C3), complement 4 (C4), and cytoplasmic and peri-nuclear anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies. A qualitative ANA serology was also non-reactive. A serologic test was not available but stool examination was done repeatedly and one exam showed egg of fasciola (Figure 1).

Case 3: Laboratory tests showed a white blood count (WBC) of 19000 cells/mL (eosinophil count of 14630 cells/mL [77%]). Peripheral blood smear was consistent with eosinophilia and leukocytosis. Stool examination done repeatedly was negative for ova or parasites.

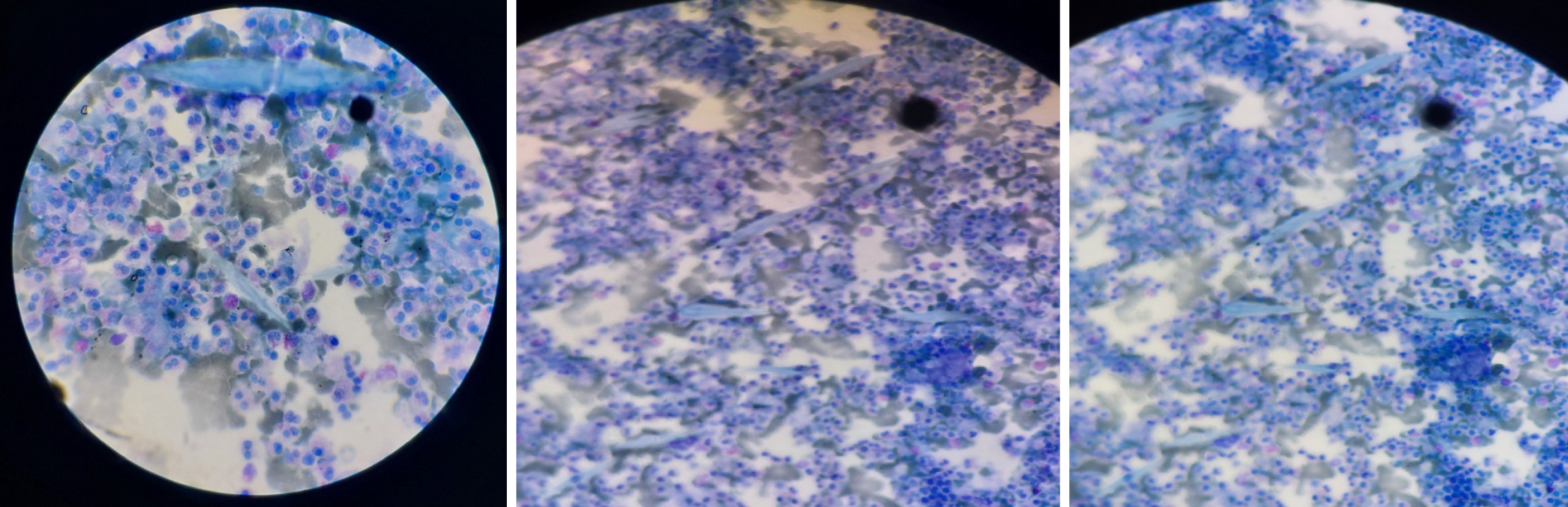

Case 4: Laboratory tests shows WBC of 9700 cells/mL (eosinophil count of 2000 cells/mL [21.2%]). Liver enzymes were elevated (aspartate transaminase 137 U/L [< 8-48 IU], alanine transaminase 252 U/L [4-36 IU/L], alkaline phosphatase 375 U/L [44-147 U/L]). Fine needle aspiration cytology from liver lesions reported a necrotic background with sheets of mixed inflammatory cells and scattered Charcot-Leyden crystals, suggesting eosinophilic liver abscess (Figure 2).

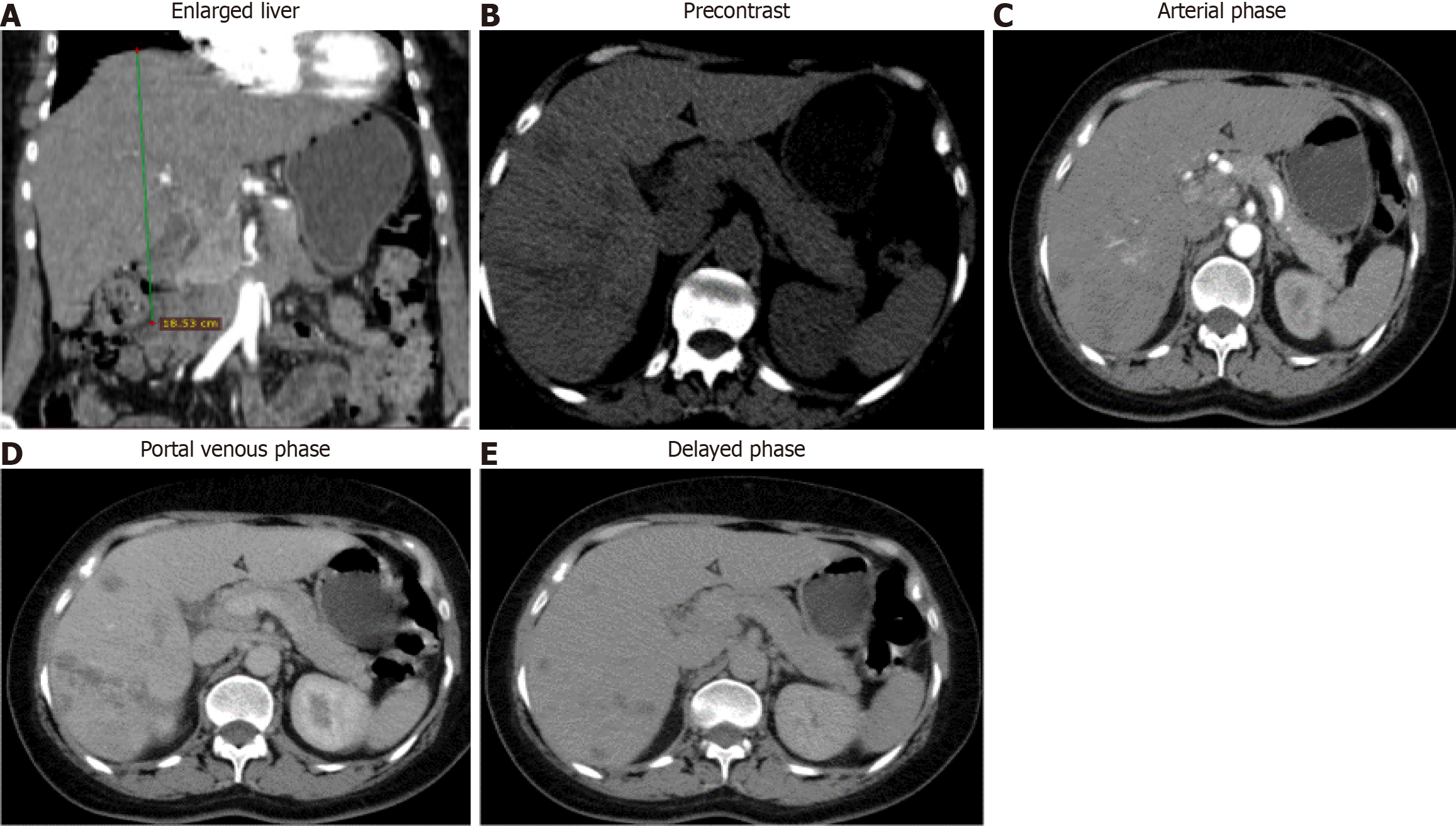

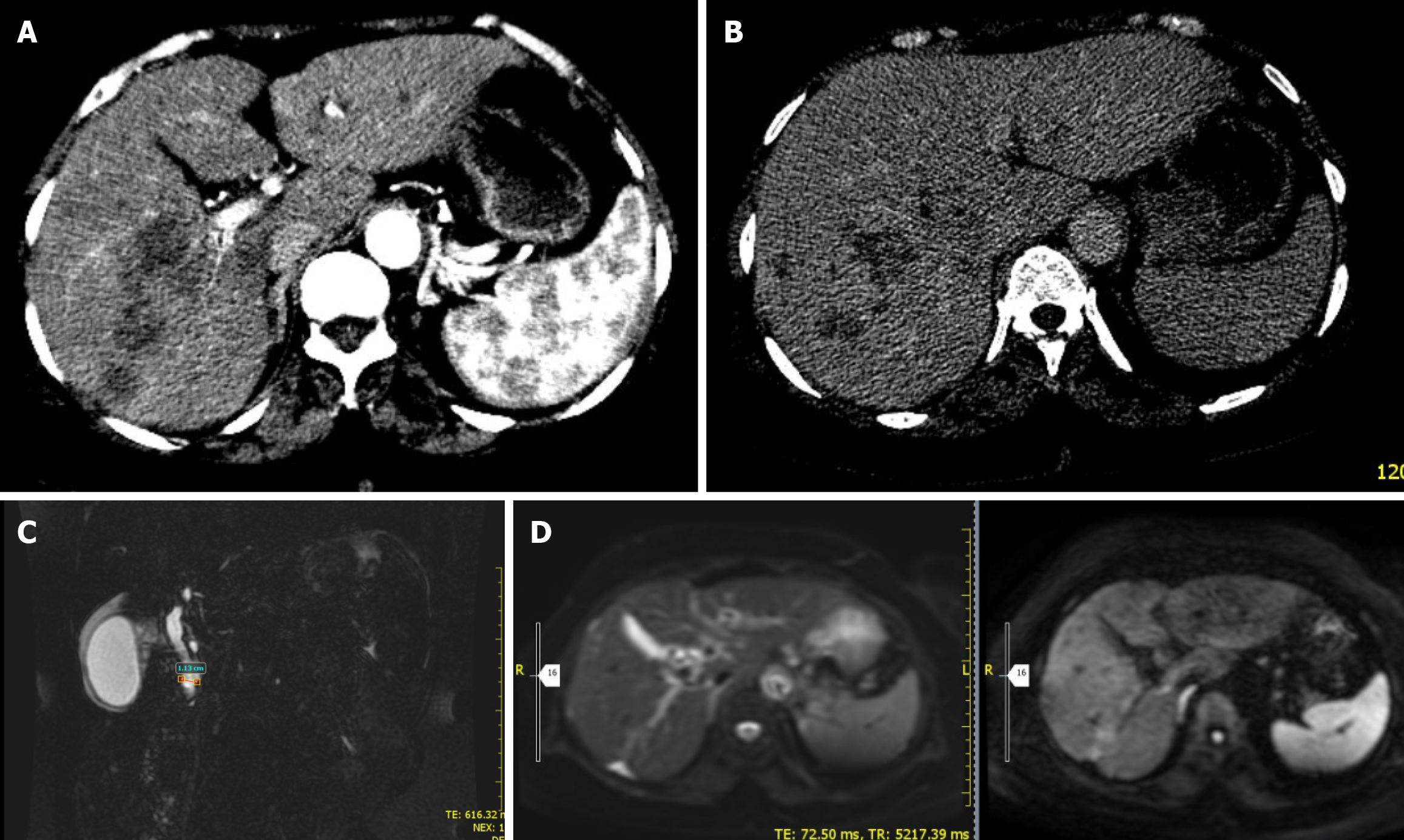

Case 1: Abdominal ultrasonography demonstrated a normal gallbladder; however, numerous hypoechoic heterogeneous lesions in the liver parenchyma were seen. Abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan showed an enlarged liver with multiple ill-defined hypodense lesions in the right lobe having minimal arterial enhancement and slight filling in delayed phase with the underlying hepatic parenchyma having internal attenuation more around the periportal area (Figure 3).

Case 2: Abdominal ultrasound and chest X-ray showed focal lesions on liver and right kidney, and multiple lesions on the lung with minimal effusion respectively. Abdominal CT scan showed hepatic segment 6 small subcapsular hypodense lesion with peripheral enhancement (Figure 4).

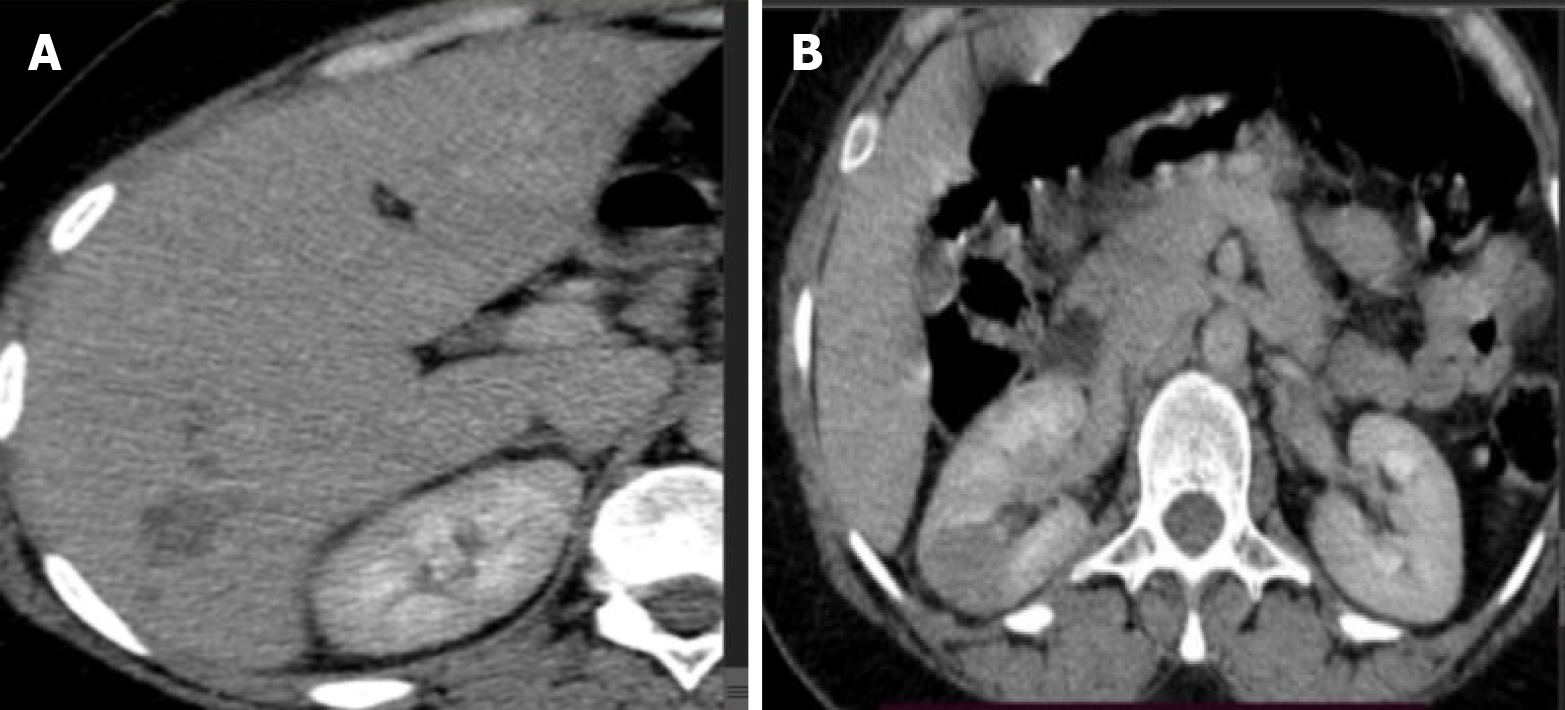

Case 3: Abdominal CT scan showed an enlarged liver with heterogeneous echo reflectivity. Multiple patchy confluent nodules were seen, predominantly iso-echoic to liver parenchyma, with scattered calcifications (Figure 5A and B).

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) study, the liver showed an ill-defined, T1 hypointense and T2 intermediate/hyperintense lesion predominantly in segments 5, 6, and 7, with moderate diffusion restriction (Figure 5C and D).

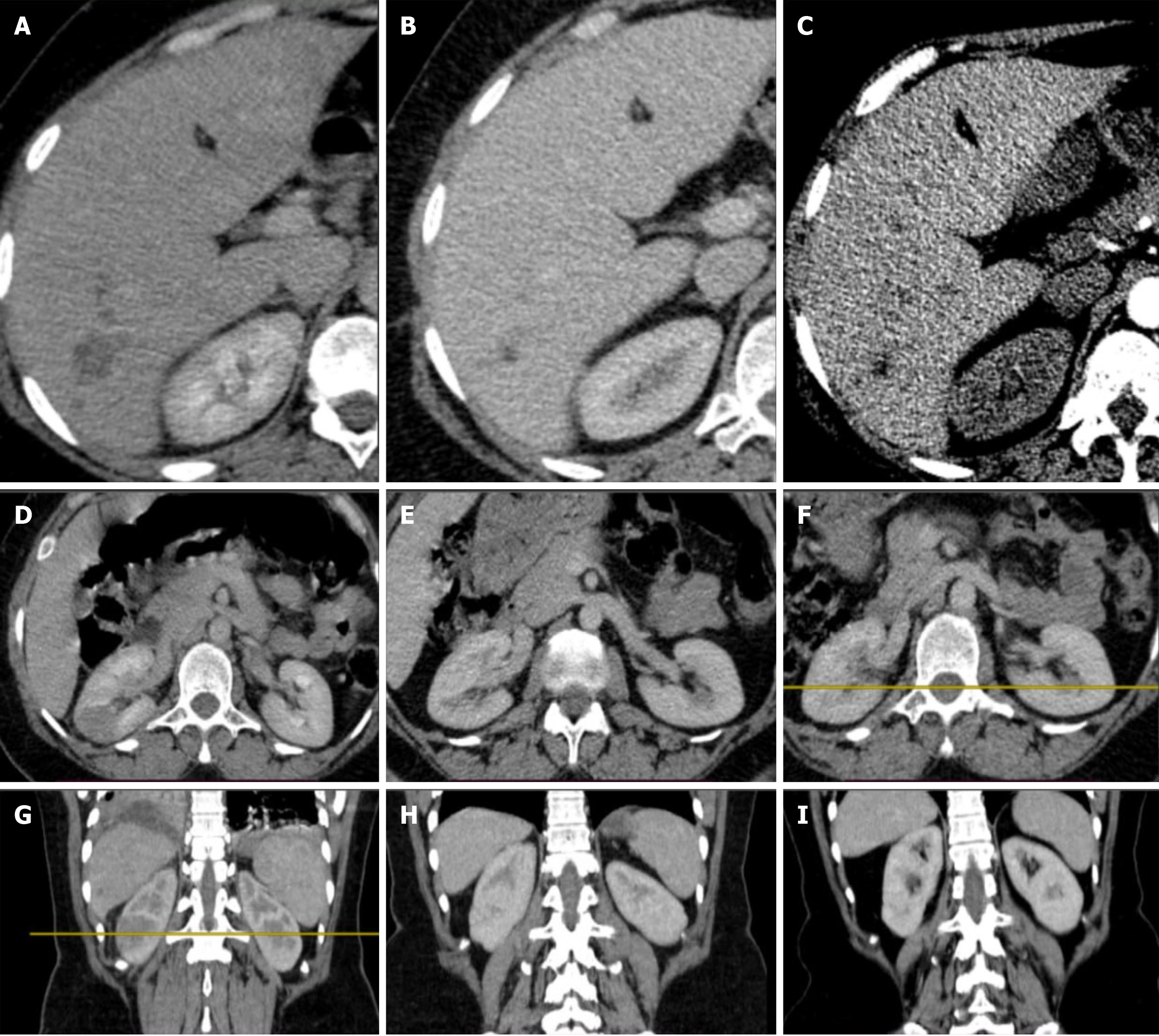

Case 4: MRCP showed dilated common bile duct with suspicious ampullary stricture and small focal liver lesions to rule out abscesses. Abdominal CT scan showed normal sized liver with segment VI 6 cm × 5.4 cm hypodense, poorly defined lesion with heterogeneous enhancement (Figure 6).

This patient’s care was managed by a multidisciplinary team comprising specialists in general internal medicine, gastroenterology, infectious disease, and oncology.

A collaborative medical team, including experts from general internal medicine, rheumatology, pulmonary medicine, and infectious disease, oversaw the management of this patient.

The patient’s treatment was guided by a consortium of specialists, including a general internist, a gastroenterologist, and an infectious disease expert.

Management of this case was conducted through a coordinated effort between general internal medicine, gastroenterology, and infectious disease specialists.

The diagnosis of hepatic fasciolasis mimicking hepatocellular carcinoma was made.

The diagnosis of autoimmune vasculitis related to hepatic fasciolasis was made.

Differentials considered were F. hepatica infection, chronic ascending cholangitis, hepatic granulomas or abscesses with reactive adenitis. The final impression of the disease was F. hepatica infection which was highly suspected based on initial eosinophilia, hepatic lesion appearance, and recent travel history to an endemic area.

With the given evidence a diagnosis of F. hepatica presenting as hepatic abscess was considered.

After careful evaluation of the clinical presentation, laboratory and imaging findings, the diagnosis was changed to F. hepatica. She was started on triclabendazole 10 mg/kg/dose which was taken for two doses 12 hours apart.

She was started on short term high dose oral steroid with pantoprazole. She was also given triclabendazole 10 mg/kg/dose which was taken for two doses 12 hours apart.

Treatment for fascioliasis was initiated with nitazoxanide for 2 weeks.

Nitazoxanide was administered at a dosage of 500 mg twice per day via the oral route for 2 weeks.

After 2 months of treatment, her abdominal pain resolved, appetite improved, eosinophilia normalized, and subsequent abdominal ultrasound showed resolved liver lesions. Evaluation during the third- and six-month follow-up showed normal findings.

After 1 month of treatment, hypereosinophilia, lung consolidation and effusion subsided; however she had right lung middle lobe peripheral atelectasis that persisted. Repeated abdominal ultrasound showed no focal lesions on the liver and kidney (Figure 7).

On subsequent visit 2 weeks later, she had significant clinical and laboratory improvement. Subsequent imaging with abdominal ultrasound and abdominal CT was unremarkable.

On a subsequent visit 2 weeks later, she had significant improvement as all her symptoms and laboratory parameters normalized. Abdominal ultrasound was also normal.

This case series illustrates the broad and often misleading clinical spectrum of hepatic fascioliasis, which frequently leads to diagnostic delays and misdiagnosis. Our patients presented with manifestations initially attributed to hepatic mali

The most critical laboratory finding across all our cases was marked peripheral eosinophilia, which serves as a key differentiator from purely bacterial or amoebic abscesses. This was definitively demonstrated in Case 4, where the initial diagnosis of a bacterial abscess was revised after antibiotic failure and the subsequent finding of an eosinophilic abscess on fine-needle aspiration. This hematologic hallmark, when combined with a careful exposure history (including travel to or residence in endemic areas and dietary habits), provides a powerful diagnostic clue.

Cross-sectional imaging is pivotal. The characteristic radiological pattern consists of multiple, small, tortuous, branching hypodense lesions, often in a subcapsular location, showing peripheral enhancement[12]. These migratory tracks, evident in Cases 1, 2, and 4, were crucial in re-directing the diagnosis away from hepatocellular carcinoma in Case 1. Furthermore, while biliary complications can mimic ascending cholangitis, as in Case 3, the concomitant presence of these parenchymal lesions and intense eosinophilia points toward the correct parasitic etiology.

Diagnostic confirmation relies on a multi-modal strategy. Direct parasitological methods, such as identifying Fasciola eggs in stool or duodenal/jejunal aspirates, are definitive but lack sensitivity, particularly in the acute phase before the parasites mature and lay eggs. For this reason, serological tests are crucial. Antibody detection assays, like the enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay using excretory-secretory antigens, offer high sensitivity during the acute and invasive stages of the disease A significant limitation of these tests, however, is their inability to reliably distinguish between past and current infections due to persistent antibodies. To address this, copro-antigen detection assays, which identify active parasite antigens in stool, are promising for confirming active infection and monitoring treatment response[6,7]. In resource-limited settings where specific tests are unavailable, a pragmatic diagnostic strategy combines strong clinical suspicion, marked eosinophilia, characteristic imaging findings, and a response to empiric anthelminthic therapy. However, in resource-limited settings where such tests are unavailable, the clinical triad of eosinophilia, suggestive imaging, and relevant exposure history becomes the de facto diagnostic algorithm, effectively employed in Cases 1 and 3.

The presentation may be complicated by extra-hepatic manifestations attributed to an allergic or immunologic response[7]. Case 2 exemplifies this, with pleural effusion, pulmonary lesions, and urticaria. Some patients develop a chronic form of the disease, persisting for over 6 months, as seen in Case 1. Other organs like the heart, eyes, skin, geni

Once a diagnosis of fascioliasis is established, management primarily consists of anthelminthic therapy. Common pharmacological options include triclabendazole and nitazoxanide[16]. Oral triclabendazole is highly effective, with cure rates typically exceeding 90%[17]. Standard regimens involve two doses of 10 mg/kg, though single-dose regimens have also demonstrated success[18-21]. While treatment failures occur, a repeated course can often achieve a cure[22,23]. Nitazoxanide serves as a well-tolerated alternative, with a recommended dosage of 500 mg twice daily for 7 days[24,25]. The dramatic response to empiric anti-helminthic therapy in all our patients, even without definitive parasitological proof in some, further supports the diagnosis and underscores the value of timely treatment.

Based on the comprehensive case series presented, hepatic fascioliasis represents a formidable diagnostic challenge, particularly in endemic regions with limited resources. This series of four cases underscores the protean clinical manifestations of F. hepatica infection, which can mimic a wide spectrum of conditions including hepatic malignancy, bacterial or amoebic abscess, autoimmune vasculitis, and ascending cholangitis. The cornerstone of accurate diagnosis rests upon a high index of suspicion, triggered by the consistent finding of marked peripheral eosinophilia and corroborated by a meticulous exposure history and characteristic imaging findings on ultrasound, CT, or magnetic resonance imaging. In settings where specific serologic testing is unavailable, these clinical and radiological clues become paramount. The documented successful outcomes with both triclabendazole and nitazoxanide affirm that timely empiric anti-parasitic therapy is highly effective, can prevent unnecessary and invasive diagnostic procedures, and significantly reduces morbidity. Therefore, enhancing clinician awareness of this neglected tropical disease is critical to improving patient outcomes and mitigating the risk of misdiagnosis.

We would like to acknowledge the patients for providing us consent to share their case history and image.

| 1. | Magaji AA, Ibrahim K, Salihu MD, Saulawa MA, Mohammed AA, Musawa AI. Prevalence of Fascioliasis in Cattle Slaughtered in Sokoto Metropolitan Abattoir, Sokoto, Nigeria. Adv Epidemiol. 2014;2014:1-5. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Cwiklinski K, O'Neill SM, Donnelly S, Dalton JP. A prospective view of animal and human Fasciolosis. Parasite Immunol. 2016;38:558-568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 14.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Carmona C, Tort JF. Fasciolosis in South America: epidemiology and control challenges. J Helminthol. 2017;91:99-109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Fürst T, Keiser J, Utzinger J. Global burden of human food-borne trematodiasis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12:210-221. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 442] [Cited by in RCA: 386] [Article Influence: 27.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Fürst T, Duthaler U, Sripa B, Utzinger J, Keiser J. Trematode infections: liver and lung flukes. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2012;26:399-419. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Caravedo MA, Cabada MM. Human Fascioliasis: Current Epidemiological Status and Strategies for Diagnosis, Treatment, and Control. Res Rep Trop Med. 2020;11:149-158. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Chai JY, Jung BK. General overview of the current status of human foodborne trematodiasis. Parasitology. 2022;149:1262-1285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Fentie T, Erqou S, Gedefaw M, Desta A. Epidemiology of human fascioliasis and intestinal parasitosis among schoolchildren in Lake Tana Basin, northwest Ethiopia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2013;107:480-486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bayu B, Asnake S, Woretaw A, Ali J, Gedefaw M, Fente T, Getachew A, Tsegaye S, Dagne T, Yitayew G. Cases of human fascioliasis in North-West Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2006;19:237-240. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Chan CW, Lam SK. Diseases caused by liver flukes and cholangiocarcinoma. Baillieres Clin Gastroenterol. 1987;1:297-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Sezgın O, Altintaş E, Tombak A, Uçbılek E. Fasciola hepatica-induced acute pancreatitis: report of two cases and review of the literature. Turk J Gastroenterol. 2010;21:183-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Salahshour F, Tajmalzai A. Imaging findings of human hepatic fascioliasis: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Rep. 2021;15:324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Xuan le T, Hung NT, Waikagul J. Cutaneous fascioliasis: a case report in Vietnam. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005;72:508-509. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Dalimi A, Jabarvand M. Fasciola hepatica in the human eye. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2005;99:798-800. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Taghipour A, Zaki L, Rostami A, Foroutan M, Ghaffarifar F, Fathi A, Abdoli A. Highlights of human ectopic fascioliasis: a systematic review. Infect Dis (Lond). 2019;51:785-792. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Keiser J, Utzinger J. Chemotherapy for major food-borne trematodes: a review. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2004;5:1711-1726. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 100] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 4.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Marcos LA, Tagle M, Terashima A, Bussalleu A, Ramirez C, Carrasco C, Valdez L, Huerta-Mercado J, Freedman DO, Vinetz JM, Gotuzzo E. Natural history, clinicoradiologic correlates, and response to triclabendazole in acute massive fascioliasis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;78:222-227. [PubMed] |

| 18. | Ibrahim N, Abdel Khalek EM, Makhlouf NA, Abdel-Gawad M, Mekky M, Ramadan HK, Abu-Elfatth A, El-Latif NA, Hassan MK, Eldeeb R, Abdelmalek M, Abd-Elsalam S, Attia H, Mohammed AQ, Aboalam H, Farouk M, Alboraie M. Clinical characteristics of human fascioliasis in Egypt. Sci Rep. 2023;13:16254. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | el-Karaksy H, Hassanein B, Okasha S, Behairy B, Gadallah I. Human fascioliasis in Egyptian children: successful treatment with triclabendazole. J Trop Pediatr. 1999;45:135-138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Graham CS, Brodie SB, Weller PF. Imported Fasciola hepatica infection in the United States and treatment with triclabendazole. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;33:1-5. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Villegas F, Angles R, Barrientos R, Barrios G, Valero MA, Hamed K, Grueninger H, Ault SK, Montresor A, Engels D, Mas-Coma S, Gabrielli AF. Administration of triclabendazole is safe and effective in controlling fascioliasis in an endemic community of the Bolivian Altiplano. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2012;6:e1720. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Branco EA, Ruas R, Nuak J, Sarmento A. Treatment failure after multiple courses of triclabendazole in a Portuguese patient with fascioliasis. BMJ Case Rep. 2020;13:e232299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Terashima A, Canales M, Maco V, Marcos LA. Observational study on the effectiveness and safety of multiple regimens of triclabendazole in human fascioliasis after failure to standard-of-care regimens. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2021;25:264-267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Rossignol JF, Abaza H, Friedman H. Successful treatment of human fascioliasis with nitazoxanide. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1998;92:103-104. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 53] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Favennec L, Jave Ortiz J, Gargala G, Lopez Chegne N, Ayoub A, Rossignol JF. Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of nitazoxanide in the treatment of fascioliasis in adults and children from northern Peru. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;17:265-270. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/