Published online Dec 26, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i36.113655

Revised: October 31, 2025

Accepted: December 15, 2025

Published online: December 26, 2025

Processing time: 116 Days and 19.5 Hours

Lower respiratory tract viral infections are a major cause of mortality in children under five years old, leading to hundreds of thousands of fatalities annually. The highest risk is observed in infants under one year old, underscoring the critical need for safe and effective antiviral protocols.

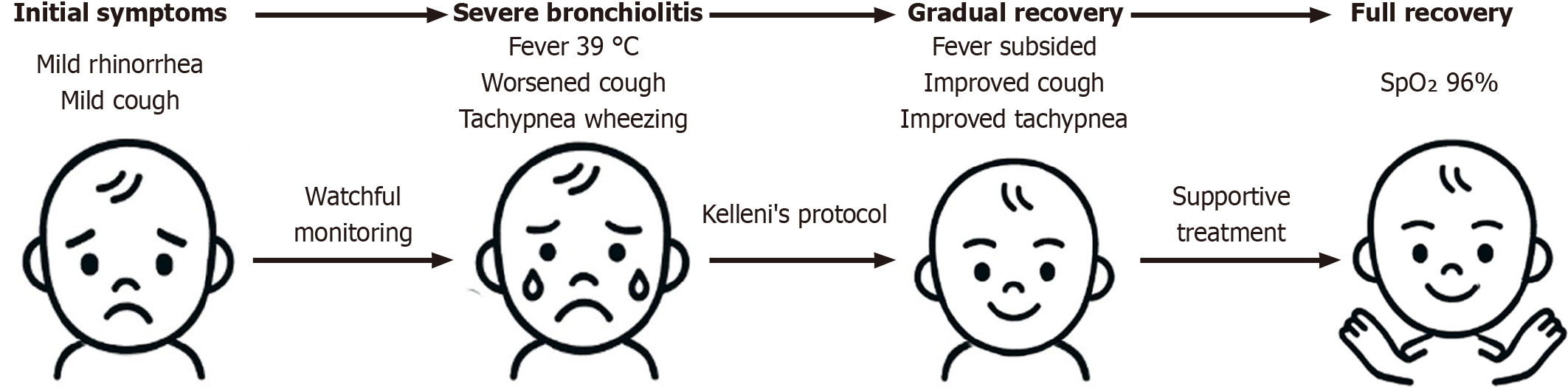

A 9-month-old infant suffered from severe bronchiolitis as manifested by high fever (39 °C), decreased appetite, tachypnea, wheezing, and oxygen desaturation (SpO2 84% on room air) and was effectively managed at home using Kelleni’s protocol, which includes age-adjusted dose of nitazoxanide (60 mg twice daily), ibuprofen and azithromycin, complemented by selective antihistaminic, anti

To the best of my knowledge, this report presents, for the first time globally, a potential of nitazoxanide within Kelleni’s protocol to early manage infants youn

Core Tip: This report presents the first documented use of nitazoxanide incorporated within Kelleni’s protocol to manage severe bronchiolitis in a 9-month-old infant. The infant presented with SpO2 84% on room air, tachypnea, and diffuse wheezing which was clinically consistent with severe viral bronchiolitis. Bronchiolitis is a leading cause of infant hospitalization and mortality worldwide, with limited effective antiviral treatments. Early administration of nitazoxanide, alongside other immunomodulatory therapies, showed clinical improvement as shown with resolution of fever and progressive improvement in in all symptoms, SpO2 rising from 84% to 92% and then 96% at full recovery in this severe case within two weeks. This approach highlights the potential to repurpose nitazoxanide and Kelleni’s protocol to safely manage severe lower viral respiratory tract infections in infants younger than one year.

- Citation: Kelleni MT. First use of nitazoxanide in Kelleni’s protocol for managing severe bronchiolitis in a 9-month-old infant: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(36): 113655

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i36/113655.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i36.113655

It’s a very alarming statistic that a child dies from pneumonia every 43 seconds as declared by UNICEF on November 2024, with most victims being younger than 1 year old[1]. Viral pneumonia is most common in children younger than 2 years and viral bronchiolitis is considered the most frequent cause of hospitalization for infants with acute lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI)[2].

Importantly, though most of these pediatric pneumonia deaths occur in developing countries with 81% deaths occurring in children younger than 2 years old, this condition still results in nearly a million pediatric hospitalizations annually in developed countries, leading to a significant economic burden. The causative viruses include respiratory syncytial virus, adenovirus, human metapneumovirus, human rhinovirus, parainfluenza virus, influenza, and corona

Meanwhile, using common antiviral drugs such as oseltamivir, peramivir or interferons, to manage viral LRTI especially in high-risk groups such as infants is deficient in terms of both efficacy[4-6] and/or safety[4,7]. Similarly, though aerosolized or oral ribavirin may be used for severe respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) in some selected high-risk children such as severe immunosuppression, it isn’t recommended for otherwise healthy infants due to lack of clear benefit and significant toxicity[8,9]. Likewise, remdesivir failed not only to show an apparent clinical efficacy in hospitalized children with mild-to-moderate coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19)[10], but also its efficacy in managing pediatric severe COVID-19 is questionable[11]. Remdesivir potential adverse effects include transaminitis, hypotension, bradycardia, premature ventricular contractions, and acute kidney injury[12-14]. Collectively, these constraints empha

Interestingly, starting in December 2024 or earlier, and consistent with the global progressive dominance of highly immune-evasive SARS-CoV-2 XEC subvariant, a new surge of viral upper and LRTI was documented in clinics across Egypt, similar to a previous surge encountered a year earlier[16]. Several peculiar manifestations were noted in adults differed from the described XEC common manifestations, including very severe prolonged cough, described as the worst since COVID-19 was first encountered, high fever exceeding 40 °C, severe body ache, change in voice and anosmia more frequently than what was previously encountered. Interestingly, during my clinical practice throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, I’ve consistently observed the evolution of SARS-CoV-2 clinically with my patients, before the new variants being officially named[15,16].

A well-nourished 9-month-old male infant whose anthropometric parameters fell within the normal percentiles for age according to the World Health Organization growth standards, initially presented with mild rhinorrhea and mild cough. Over 5 days, the symptoms progressed to include a troublesome, persistent cough, fever up to 39 °C, decreased appetite, tachypnea, mild wheezing, irritability, and low oxygen saturation (SpO2 84% on room air) (Table 1).

| Day | Clinical events and findings | Key actions |

| Day 0 | Onset of mild rhinorrhea and cough after exposure to family members with viral laryngitis | Watchful monitoring |

| Day 3 | Cough worsened, mild change in voice. No fever | Single daily ibuprofen dose started |

| Day 5 | Fever up to 39 °C, decreased appetite, tachypnea, mild wheezing, SpO2 = 84% (room air) | Azithromycin and ibuprofen initiated. Nitazoxanide (60 mg twice daily) added based on uridine diphosphate-glucuronosyltransferase 1A1 enzyme maturation data (Strassburg et al[23], 2002) |

| Day 6 | Fever subsided; wheezing more evident; no signs of respiratory distress or consolidation | Ibuprofen discontinued; paracetamol as needed |

| Day 7-10 | Gradual improvement of cough, tachypnea and general condition; SpO2 = 92% | Continued hydration and supportive care including alpha amylase, levocetrizine and benproperine |

| Day 14 | Full clinical recovery; SpO2 = 96% (room air) | All treatments completed |

| Day 28 | Follow-up showed sustained clinical recovery. No deterioration or relapse |

The infant developed mild upper respiratory symptoms (day 0) that progressively worsened despite initial supportive care. Cough severity increased with a change in voice by day 3. By day 5, fever, decreased appetite, tachypnea, wheezing, irritability, and hypoxia developed. Close clinical monitoring and Kelleni’s protocol-based treatment led to gradual improvement and full recovery over two weeks.

The infant had no prior significant illnesses or hospitalizations. Breastfed and with normal growth parameters.

The infant had appropriate nutritional status and hydration. He became infected soon after both of his elder sisters and his mother had recovered from viral laryngitis during the community-wide surge of respiratory tract infections (RTIs) attributed to the highly immune-evasive SARS-CoV-2 XEC subvariant. The likely chain of transmission began with the elder sister, who developed a prolonged cough and mild fever, followed by her younger sister and then the mother. No significant chronic or genetic diseases were noted.

The infant was alert but irritable, with tachypnea but no distress. Lung auscultation revealed scattered bilateral wheezing and fine crackles without consolidation. Cardiac and abdominal exams were normal. Oxygen saturation was initially low (84%) but improved progressively.

No laboratory tests were performed owing to clinical improvement and home-based care combined with oxygen saturation monitoring.

No imaging studies were conducted as clinical signs did not warrant hospitalization or investigation, minimizing unnecessary interventions in a resource-limited setting.

The diagnosis was made clinically as SARS-CoV-2 severe viral bronchiolitis, the differential diagnosis included RSV, influenza, and bacterial pneumonia. Notably, Kelleni’s protocol has managed RSV and influenza viral RTI, and it’s globally recognized that the clinical manifestations of these and other RTIs including SARS-CoV-2 are mostly similar and Kelleni’s protocol was similarly practiced managing them[17]. However, RSV and influenza were less likely because the clinical course was afebrile at onset, lacked otalgia or conjuctivits[17], and coincided with a confirmed community surge of SARS-CoV-2 XEC variant infections.

Bacterial pneumonia was considered but excluded based on the ongoing clinical prognosis. The infant demonstrated rapid and sustained improvement in respiratory rate, oxygen saturation, and general condition after receiving nitazoxanide and azithromycin, without the need to escalate to broader-spectrum antibiotics such as amoxicillin/clavulanate. There were no clinical signs suggestive of bacterial pneumonia, such as focal crackles, asymmetric air entry, persistent unresponsive high fever, or toxic appearance. The absence of deterioration or relapse after discontinuation of therapy further supported a non-bacterial etiology (Table 1). The findings observed in this infant were consistent with severe viral bronchiolitis.

Tailored personalized Kelleni’s protocol, including nitazoxanide, ibuprofen, azithromycin and supportive medications, was practiced managing this infant as illustrated in the discussion.

Notably, the infant showed clinical improvement and by the end of this described treatment course, tachypnea was decreasing and SPO2 reached 92% at room temperature. The cough was gradually improving, yet it took nearly two weeks for full clinical recovery and SPO2 returned to a normal level of 96% at room temperature (Figure 1). The infant tolerated all medications well without adverse effects. Follow-up emphasized clinical evaluation and pulse oximetry to ensure sustained recovery.

The infant was infected shortly after several family members developed respiratory infections consistent with the SARS-CoV-2 XEC subvariant. His family was treated using nitazoxanide and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs as part of Kelleni’s protocol[17], to be noted that his 6-year-old sister had an unusual prolonged persistent mild cough that was only relieved when azithromycin was added to nitazoxanide and ibuprofen (full Kelleni’s protocol). Importantly, many adult patients suffering from severe COVID-19 were similarly effectively managed at home with Kelleni’s protocol and didn’t require laboratory or radiologic investigations; a particularly practical advantage given the significant socioeconomic challenges encountered in resource-limited settings as in Egypt and other African and developing countries.

Although no fever was encountered in the first few days, ibuprofen was administered in a single daily appropriate dose wishing to abort the progression of the viral RTI as was practiced with his elder sisters. However, unlike his sisters, the infant didn’t receive nitazoxanide which is permitted for infants 1 year old and older. When fever was detected, I’ve promptly administered azithromycin 10 mg/kg orally once daily, and oral ibuprofen 5 mg/kg/dose three times on the first day and twice on the second day. Notably, azithromycin plays an immunomodulatory role within Kelleni’s protocoland it also helps prevent or treat secondary bacterial infections in patients experiencing rising fever, particularly in high-risk groups. When the fever subsided, wheezing became more evident along with crackles upon auscultation. Throughout his illness, no increased work of breathing was observed, and no areas of decreased air entry were detected upon auscultation. The clinical diagnosis was bronchiolitis.

Azithromycin was continued for a total of five days, and if clinical improvement hadn’t been observed, particularly regarding the rising fever, amoxicillin/clavulanate would have been added to address a possible secondary bacterial infection unresponsive to azithromycin which is currently challenged by the risk of rising global resistance; however, this risk is balanced by the clear evidence of pediatric survival benefit associated with azithromycin use[16,18]. However, Amoxicillin/clavulanate wasn’t required due to clinical improvement.

Due to the increased wheezing, I made the decision to stop administering ibuprofen and only use paracetamol when fever exceeded 38 °C, which was done for one day. I’ll continue to adopt this cautious traditional approach until more rigorous studies definitively resolve the conflicting evidence regarding a potential ibuprofen-induced bronchoconstriction in some patients[19]. Similarly, I don’t recommend the routine prescription of bronchodilators for COVID-19 patients experiencing cough and wheezing unless they have an established diagnosis of asthma[20,21]. Good hydration, mainly through breast feeding, was always maintained throughout the illness.

Meanwhile, concomitant with azithromycin administration, I’ve decided to add nitazoxanide in a dose of 60 mg (3 mL), instead of the usual 100 mg (5 mL), twice daily for five days, instead of three days that I’ve used to prescribe for infants aged 1 years to 3 years. Importantly, I decided to add nitazoxanide, with this adjusted dose and duration, after careful evaluation of the developmental maturation of the uridine diphosphate-glucuronosyltransferase 1A1 (UGT1A1) enzyme, which is primarily responsible for the glucuronidation of tizoxanide, the active metabolite of nitazoxanide, as nitazoxanide metabolism occurs first by hydrolysis to tizoxanide and then glucuronidation through UGT1A1[22]. Notably, UGT1A1 is responsible for the metabolism of bilirubin and its expression and activity show substantial development at 6 months of age[23], supporting the safe metabolic handling of nitazoxanide in this 9-month-old infant. The extended treatment duration was selected to enhance antiviral and immunomodulatory effects while maintaining a conservative total exposure suitable for this age group. Thus, though nitazoxanide hasn’t yet been approved for infants younger than 12 months; however, these pharmacological studies provided me with the scientific justification for its off-label use in this patient. Interestingly, interferon α1b was administered to manage infant bronchiolitis which is outside its approved indications though it isn’t in routine guideline care; its use in infants younger than one year was similarly off label[24]. Moreover, oseltamivir was first administered to infants younger than one year as an Emergency Use Authorization allowed its administration to combat the 2009 influenza A (H1N1) pandemic[25].

Importantly, as the cough was very troublesome (Figure 1), I used levocetrizine drops 1.25 mg at bedtime, a dose within the established safe range for infants aged 6 months and older as supported by clinical safety data and pediatric dosing guidelines, primarily to help alleviate this troublesome cough induced by post nasal drip and affecting the infant’s sleep and comfort while monitoring for any adverse effects[26-28]. Additionally, I’ve added a single dose of benproperine syrup (2.5 mL containing 8.3 mg benproperine) at bedtime to aid achieving better sleep. Notably, similar to nitazoxanide, benproperine isn’t prescribed for infants younger than one year. However, unlike nitazoxanide, this low dose of benproperine is adopted by many expert Egyptian pediatricians for years to alleviate troublesome cough in this age group and I’ve also checked its metabolism that occurs through hydrolysis and glucuronidation[29]. Moreover, benproperine is currently repurposed against pancreatic cancer due to some immune-modulatory properties[30] and I suggest that its potential immunomodulatory effect could reveal efficacy in managing COVID-19 both in children and adults.

Additionally, I’ve also added alpha amylase syrup 600 U (Comité Européen de l’Industrie des Parfums et des Produits cosmétiques, CEIP) (3 mL) twice daily during the daytime to help relieve the pulmonary secretions. Alpha amylase was selected as the mucolytic agent because it hydrolyzes polysaccharide components of airway secretions, thereby reducing mucus viscosity and facilitating clearance. Although it is not routinely recommended in standard bronchiolitis guidelines, it remains available in several countries as an approved expectorant with a long record of safe and effective pediatric use. The infant responded with progressive improvement in secretion clearance and cough relief without adverse events. I’ve preferred alpha amylase over ambroxol, though both drugs are known to be well tolerated in this age group, largely due to alpha amylase’s exceedingly rare potential to induce idiosyncratic hypersensitivity reactions. Nevertheless, ambroxol may offer greater advantages in early home management of COVID-19 because of its suggested immunomodulatory properties[31], to be noted that treatment with ambroxol didn’t have a significant effect on mortality of COVID-19 hospitalized patients when compared with non-ambroxol patients[32]. Double-arm clinical trials are recommended to directly compare the efficacy of both drugs. Alpha amylase was administered for five days and benproperine for three days, after which the cough and wheezing have significantly improved.

Potential pharmacological interactions among azithromycin, nitazoxanide, ibuprofen, levocetirizine, alpha-amylase, and benproperine were carefully considered. No major interactions were previously documented as all agents are meta

Importantly, from December 2024 until the winter passed, I decided to start the full Kelleni’s protocol for five days and discontinue the “watchful monitoring” in all high-risk groups. Interestingly, a year ago, I’ve adopted a similar early management and post exposure approach for the high risk groups but for three days and not necessarily the full protocol[16]. After that surge passed, I returned to “watchful monitoring” before adding azithromycin that was mainly added for those experiencing high fever and less commonly to manage persistent cough[16] that wasn’t encountered in that frequency except after this new surge appeared. At periods of SARS-CoV-2 surge, the full Kelleni’s approach, when initiated earlier in the course of a respiratory viral illness in a high risk patient, has effectively aborted the progression of this current highly immune-evasive viral RTI/variant resulting in symptoms similar to a mild common cold as it did with all the previous SARS-CoV-2 variants which mostly responded to only some drugs of Kelleni’s protocol for a shorter duration[16,17]. When comparing this approach to patients who attended the clinic for treatment at a relatively later stage, it was obviously superior in reducing morbidity.

In situations of extreme public health crisis, such as pandemics and where millions of infant lives are at stake, such as in severe viral LRTIs, the ethical imperative dictates that physicians must actively pursue every scientifically sound clue to save lives. Moreover, the development of all medical protocols often follows a trajectory beginning with compelling case reports that, through repeated validation, evolve into the foundation for rigorous clinical trials, a process repeatedly advocated for in the evolution of medical knowledge. Kelleni’s protocol is suggested to exemplify this merit, representing a potential affordable empiric broad spectrum antiviral protocol that warrants further investigation for possible global adoption.

To the best of my knowledge, this report is the first to describe administering nitazoxanide to manage severe SARS-CoV-2/viral RTI in infants younger than one year at home. Repurposing nitazoxanide and Kelleni’s protocol for the early management of viral pneumonia and bronchiolitis in infants aged six months and older may offer a promising approach to reduce morbidity and mortality associated with these infections as well as their huge socioeconomic burdens; however, larger clinical studies are warranted to confirm safety and efficacy.

| 1. | Kudagammana ST, Premathilaka S, Vidanapathirana G, Kudagammana W. Childhood mortality due to pneumonia; evidence from a tertiary paediatric referral center in Sri Lanka. BMC Public Health. 2024;24:3351. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Tian J, Wang XY, Zhang LL, Liu MJ, Ai JH, Feng GS, Zeng YP, Wang R, Xie ZD. Clinical epidemiology and disease burden of bronchiolitis in hospitalized children in China: a national cross-sectional study. World J Pediatr. 2023;19:851-863. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Feng Q, Wang J, Wang X, Tian J, Zhang L, Dilmurat D, Liu M, Ai J, Feng G, Zeng Y, Wang R, Xie Z. Clinical epidemiological characteristics of hospitalized pediatric viral community-acquired pneumonia in China. J Infect. 2025;90:106450. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bassett HK, Coon ER, Mansbach JM, Snow K, Wheeler M, Schroeder AR. Misclassification of Both Influenza Infection and Oseltamivir Exposure Status in Administrative Data. JAMA Pediatr. 2024;178:201-203. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Gupta YK, Meenu M, Mohan P. The Tamiflu fiasco and lessons learnt. Indian J Pharmacol. 2015;47:11-16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Mesic A, Jackson EK, Lalika M, Koelle DM, Patel RC. Interferon-based agents for current and future viral respiratory infections: A scoping literature review of human studies. PLOS Glob Public Health. 2022;2:e0000231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Witcher R, Tracy J, Santos L, Chopra A. Outcomes and Adverse Effects With Peramivir for the Treatment of Influenza H1N1 in Critically Ill Pediatric Patients. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther. 2019;24:497-503. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Hoover J, Eades S, Lam WM. Pediatric Antiviral Stewardship: Defining the Potential Role of Ribavirin in Respiratory Syncytial Virus-Associated Lower Respiratory Illness. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther. 2018;23:372-378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Otto WR, Lee G, Thurm CW, Hersh AL, Gerber JS. Ribavirin Use in Hospitalized Children. J Pediatric Infect Dis Soc. 2022;11:386-387. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Shoji K, Asai Y, Akiyama T, Tsuzuki S, Matsunaga N, Suzuki S, Iwamoto N, Funaki T, Miyairi I, Ohmagari N. Clinical efficacy of remdesivir for COVID-19 in children: A propensity-score-matched analysis. J Infect Chemother. 2023;29:930-933. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Kautsch K, Wiśniowska J, Friedman-Gruszczyńska J, Buda P. Evaluation of the safety profile and therapeutic efficacy of remdesivir in children with SARS-CoV-2 infection - a single-center, retrospective, cohort study. Eur J Pediatr. 2024;183:591-598. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Schulz A, Huynh N, Heger M, Bakir M. Adverse effects of remdesivir for the treatment of acute COVID-19 in the pediatric population: a retrospective observational study. Mol Cell Pediatr. 2024;11:2. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Devgun JM, Zhang R, Brent J, Wax P, Burkhart K, Meyn A, Campleman S, Abston S, Aldy K; Toxicology Investigators Consortium FACT Study Group. Identification of Bradycardia Following Remdesivir Administration Through the US Food and Drug Administration American College of Medical Toxicology COVID-19 Toxic Pharmacovigilance Project. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:e2255815. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wu B, Luo M, Wu F, He Z, Li Y, Xu T. Acute Kidney Injury Associated With Remdesivir: A Comprehensive Pharmacovigilance Analysis of COVID-19 Reports in FAERS. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:692828. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Kelleni MT. The African Kelleni's roadmap using nitazoxanide and broad-spectrum antimicrobials to abort returning to COVID-19 square one. Inflammopharmacology. 2023;31:3335-3338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Kelleni MT. Real-life practice of Kelleni's protocol in treatment and post exposure prophylaxis of SARS-CoV-2 HV.1 and JN.1 subvariants. World J Virol. 2025;14:107903. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Kelleni MT. Real-life practice of the Egyptian Kelleni's protocol in the current tripledemic: COVID-19, RSV and influenza. J Infect. 2023;86:154-225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Medugu N, Michelow IC, Poole C, Obaro SK. Azithromycin mass drug administration: balancing survival benefits and risks in children. Lancet Infect Dis. 2025;S1473-3099(25)00363. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Baxter L, Cobo MM, Bhatt A, Slater R, Sanni O, Shinde N. The association between ibuprofen administration in children and the risk of developing or exacerbating asthma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pulm Med. 2024;24:412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Matera MG, Rogliani P, Zanasi A, Cazzola M. Bronchodilator therapy for chronic cough. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2017;47:88-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Becker LA, Hom J, Villasis-Keever M, van der Wouden JC. Beta2-agonists for acute cough or a clinical diagnosis of acute bronchitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2015:CD001726. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Hanioka N, Isobe T, Saito K, Nagaoka K, Mori Y, Jinno H, Ohkawara S, Tanaka-Kagawa T. Glucuronidation of tizoxanide, an active metabolite of nitazoxanide, in liver and small intestine: Species differences in humans, monkeys, dogs, rats, and mice and responsible UDP-glucuronosyltransferase isoforms in humans. Comp Biochem Physiol C Toxicol Pharmacol. 2024;283:109962. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Strassburg CP, Strassburg A, Kneip S, Barut A, Tukey RH, Rodeck B, Manns MP. Developmental aspects of human hepatic drug glucuronidation in young children and adults. Gut. 2002;50:259-265. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 209] [Cited by in RCA: 220] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Chen L, Shi M, Deng Q, Liu W, Li Q, Ye P, Yu X, Zhang B, Xu Y, Li X, Yang Y, Li M, Yan Y, Xu Z, Yu J, Xiang L, Tang X, Wan G, Cai Q, Wang L, Hu B, Xie L, Li G, Xie L, Liu X, Liu C, Li L, Chen L, Jiang X, Huang Y, Wang S, Guo J, Shi Y, Li L, Wang X, Zhao Z, Li Y, Liu Y, Fu Q, Zeng Y, Zou Y, Liu D, Wan D, Ai T, Liu H. A multi-center randomized prospective study on the treatment of infant bronchiolitis with interferon α1b nebulization. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0228391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Çiftçi E, Karbuz A, Kendirli T. Influenza and the use of oseltamivir in children. Turk Pediatri Ars. 2016;51:63-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | de Blic J, Wahn U, Billard E, Alt R, Pujazon MC. Levocetirizine in children: evidenced efficacy and safety in a 6-week randomized seasonal allergic rhinitis trial. Pediatr Allergy Immunol. 2005;16:267-275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Lee JH, Lee JW, An J, Won HK, Park SY, Lee JH, Kang SY, Kanemitsu Y, Kim HJ, Song WJ. Efficacy of non-sedating H1-receptor antihistamines in adults and adolescents with chronic cough: A systematic review. World Allergy Organ J. 2021;14:100568. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | May BC, Gallivan KH. Levocetirizine and montelukast in the COVID-19 treatment paradigm. Int Immunopharmacol. 2022;103:108412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Li Y, Zhong DF, Chen SW, Maeba I. Identification of some benproperine metabolites in humans and investigation of their antitussive effect. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2005;26:1519-1526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Zhang H, Zhang Z, Huang Y, Qin S, Zhou L, Weng N, Liu J, Yang M, Zhang X, Lu Y, Ma L, Zheng S, Li Q. Repurposing antitussive benproperine phosphate against pancreatic cancer depends on autophagy arrest. Mol Oncol. 2021;15:725-738. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Takeda K, Miyahara N, Matsubara S, Taube C, Kitamura K, Hirano A, Tanimoto M, Gelfand EW. Immunomodulatory Effects of Ambroxol on Airway Hyperresponsiveness and Inflammation. Immune Netw. 2016;16:165-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Lu Y, Yang QQ, Zhuo L, Yang K, Kou H, Gao SY, Hu W, Jiang QL, Li WJ, Wu DF, Sun F, Cheng H, Zhan S. Ambroxol for the treatment of COVID-19 among hospitalized patients: A multicenter retrospective cohort study. Front Microbiol. 2022;13:1013038. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/