Published online Dec 16, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i35.115700

Revised: November 26, 2025

Accepted: December 10, 2025

Published online: December 16, 2025

Processing time: 54 Days and 18.3 Hours

Median sternotomy has been considered the gold standard approach for anterior mediastinal tumor resection. However, recent advances in video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery and robotic-assisted thoracoscopic surgery with carbon dioxide insufflation have allowed minimally invasive approaches even for large and locally invasive tumors of the upper-anterior mediastinum. The subxiphoid robotic optical approach is a recently developed technique for accessing the med

To evaluate the safety, feasibility, and outcomes of a robotic subxiphoid approach for the resecting of large/invasive mediastinal tumors.

Between July 2024 and September 2025, 12 patients underwent subxiphoid robotic mediastinal resection. The diameter of the operated lesions ranged from 30 mm to 70 mm. A 3 cm subxiphoid incision was made at the subxiphoid level for GelPort placement, allowing for optical port access. Two operating ports were placed at the sixth intercostal space bilaterally. Carbon dioxide insufflations (8-10 mmHg) enlarged the surgical field, improving visualization of critical anatomical land

The mean operating time was 170.2 minutes, and the median hospital stay was 3.5 days. No major postoperative complications occurred. Two conversions were necessary: One with a lateral robotic approach due to previous abd

Subxiphoid robotic approach is a safe, effective technique for extended thymectomy, fulfilling both oncological and myasthenia gravis surgical objectives.

Core Tip: The subxiphoid robotic-assisted thoracic approach is an excellent alternative to traditional unilateral robotic and video-assisted minimally invasive techniques for the treatment of anterior mediastinal tumors. This method provides an uno

- Citation: Pardolesi A, Ferrari M, Leuzzi G, Cioffi U, Cioffi G, Solli P. Robotic subxiphoid surgical approach for mediastinal lesions: One-year experience. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(35): 115700

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i35/115700.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i35.115700

Thymectomy is a well-known approach to the surgical management of anterior mediastinal masses, particularly thy

The subxiphoid VATS approach thus allowed direct access to the anterior mediastinum without requiring any intercostal cuts. Here, there is broad exposure to both pleural cavities, allowing easy en bloc resection of thymic tissue together with the surrounding adipose tissue, significantly reducing postoperative pain and discomfort[5,6]. The use of robotic-assisted thoracic surgery (RATS) has really taken the advantages of minimally invasive techniques to the next level. These robotic systems offer a three-dimensional view, help reduce tremor, and come with wristed instruments, which allow for precise dissection in those tricky, hard-to-reach areas of the chest. This is particularly useful in thymic surgery, where careful handling near the innominate vein, phrenic nerves, and pericardium is essential. Numerous studies and meta-analyses have demonstrated that robotic thymectomy is associated with reduced intraoperative blood loss, fewer complications, shorter hospital stays, and lower rates of incomplete resection compared to sternotomy, while maintaining operative times comparable to VATS[7-9]. The robotic subxiphoid approach represents a further evolution in minimally invasive access to the mediastinum. Carbon dioxide (CO2) insufflation, while maintaining double-lung ven

A retrospective, single-center study began the initial experience with the robotic subxiphoid approach for anterior mediastinal lesions. Twelve patients who underwent surgery between July 2024 and September 2025 at the Division of Thoracic Surgery, Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori (Milan, Italy), were selected. Standardized pro

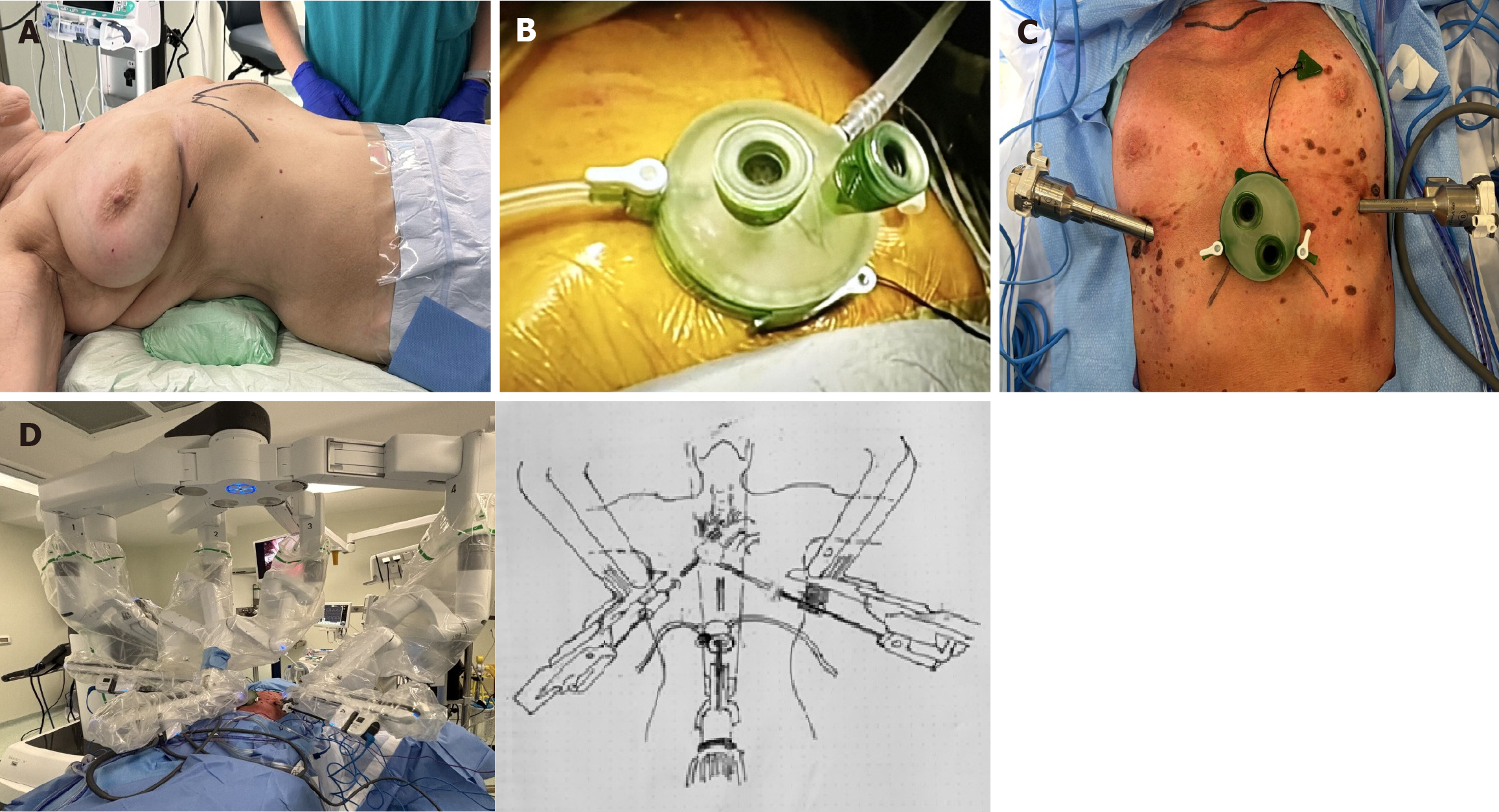

Patient position: All patients were placed in the supine position, with a roll positioned beneath the back at the level of the lower third of the sternum to enhance exposure of the subxiphoid margin. The left arm was extended and rested on a padded L-shaped support, while the right arm was positioned on a padded bar adjacent to the patient’s right side (Figure 1A).

Anesthetic management: Anesthetic management for robotic thoracic surgery followed similar protocols to those employed in open and VATS procedures[14]. All patients underwent general anesthesia with a double-lumen end

Port placement and docking: The procedure began with a 3 cm transverse incision, positioned 1 cm below the xiphoid process. The rectus abdominis fascia was cut vertically, and the muscle was gently detached from the xiphoid. Finger blunt dissection was performed to free the posterior surface of the sternum. A GelPort single-port device was introduced through the subxiphoid incision, allowing for CO2 insufflation at 8-10 mmHg (Figure 1B). The mediastinal pleura was dissected to obtain bilateral entry into the thoracic cavity. Robotic ports were placed through two additional 1 cm skin incisions in the sixth intercostal space along the midclavicular line on each side (Figure 1C). The da Vinci Xi surgical system (Intuitive Surgical, Sunnyvale, CA, United States) was docked using three arms: Arm 1: An 8-mm port was positioned in the right sixth intercostal space along the midclavicular line. Arm 2: An 8-mm port was placed in the subxiphoid region and housed the camera with a 30° oblique view. Arm 3: An 8-mm port was positioned in the left sixth intercostal space along the midclavicular line. Docking time was under 5 minutes in all the procedures. A fenestrated bipolar forceps was introduced through the left port, while a bipolar Maryland dissector was inserted through the right port (Figure 1D).

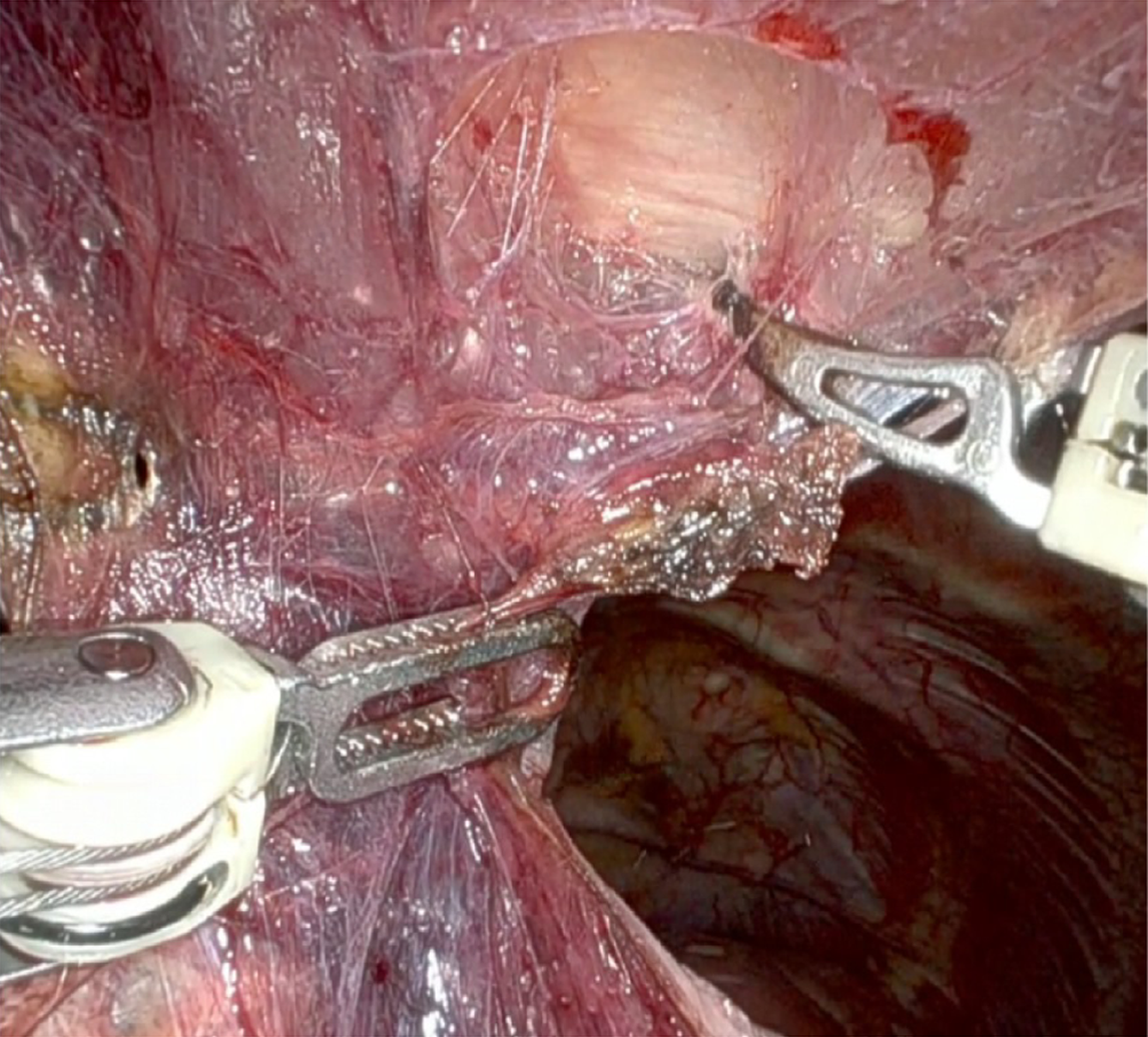

Surgical steps: The procedure began with a careful blunt dissection of the tissues located beneath the sternum, starting at the lower end and proceeding upward toward the manubrium (Figure 2). This method, combined with CO2 insufflation, created a large operative field in the anterior mediastinum, allowing clear visualization of important anatomical features, such as the internal mammary arteries and the phrenic nerves. Next, the inferior thymic horns were cut along the pericardial surface. To ensure safe and efficient hemostasis, we used Syncrosyl to divide the major arteries and veins supplying the mediastinal fat. Dissection was extended superiorly from the pericardium to expose the ascending aorta and the superior vena cava. Adhesions to the lung parenchyma were meticulously divided using either a bipolar Maryland instrument or Syncrosyl. After dissecting the mediastinal tissue away from the right phrenic nerve, the dissection proceeded in a cranial direction from the superior vena cava to identify and expose the innominate vein. With the innominate vein clearly visualized, the upper thymic horns were removed from the neck using blunt dissection directly above the vein. The thymic vein was divided using Syncrosyl, eliminating the need for additional hemostatic devices, such as clips or Hem-o-lok. Finally, the resected specimen was extracted from the chest cavity through the subxiphoid utility incision using an endoscopic retrieval bag.

Preference cards: (1) 30-degree 10 mm robotic camera; (2) CO2 insufflation device (8-10 mmHg); (3) Tissue retractor: GelPort (Applied Medical, CA, United States), robotic trocars; (4) 8 mm robotic instruments: EndoWrist bipolar Maryl, Fenestrated bipolar forceps, and Synhroseal; and (5) Endoscopic retrieval bag.

The following parameters were analyzed: Patient age, sex, lesion size, histopathological diagnosis, Masaoka stage (for thymomas), operative time, postoperative complications, conversion to alternative approaches, and length of hospital stay. Continuous variables are presented as mean or median values, while categorical variables are reported as fre

A total of 12 patients (9 females, 3 males; mean age 55.2 ± 15.6 years; range 29-77 years) underwent robotic subxiphoid resection of anterior mediastinal lesions during the study period. The mean maximal lesion diameter was 39.0 ± 22.0 mm (range 14-70 mm).

The mean operative time was 202.9 ± 44.6 minutes (range 99-290 minutes). The median length of the postoperative hospital stay was 3.58 ± 1.4 days (range 2-4 days). No major postoperative complications were observed. Two conversions occurred: One to a lateral robotic approach due to adhesions from prior abdominal surgery, and one to sternotomy because of tumor invasion of the aortic arch.

Histological examination revealed nine thymic lesions (including thymomas of different subtypes, thymic hyperplasia, and cysts) and one solitary fibrous tumor. Among the thymomas, Masaoka staging showed two cases at stage IIA and one case at stage IIB.

When stratified by diagnosis, operative and perioperative outcomes were consistent across subgroups (Table 1). Thymomas represented the majority of cases, with a mean lesion diameter ranging from 9 mm to 70 mm. Patients with thymic hyperplasia had the largest mean lesion size (69 mm), while those with micronodular thymoma and thymic cysts had the smallest.

| Number | Sex | Age (years) | Diameter lesion (mm) | Operation time (minutes) | Diagnosis | Masaoka stage | Hospital stays (days) |

| 1 | Female | 77 | 60 | 290 | Thymoma AB | IIA | 6 |

| 2 | Male | 44 | 32 | 220 | Thymoma AB | IIA | 4 |

| 3 | Female | 53 | 53 | 185 | Thymoma cyst | N/A | 5 |

| 4 | Female | 62 | 9 | 180 | Thymoma A | I | 5 |

| 5 | Female | 29 | 68 | 210 | Thymic hyperplasia | N/A | 5 |

| 6 | Male | 66 | 18 | 230 | Thymoma cyst | N/A | 4 |

| 7 | Female | 74 | 14 | 180 | Thymic cyst | N/A | 3 |

| 8 | Female | 29 | 70 | 197 | Thymic hyperplasia | N/A | 3 |

| 9 | Male | 60 | 36 | 180 | Micronodular thymoma | IIb | 2 |

| 10 | Female | 61 | 30 | 252 | Thymoma B1 | IIa | 3 |

| 11 | Female | 67 | 50 | 212 | Thymoma B1-B2 | IIb | 2 |

| 12 | Female | 40 | 15 | 99 | Thymoma B2 | I | 1 |

| 55.2 ± 15.6 | 37.9 ± 20.9 | 202.9 ± 44.6 | 3.58 ± 1.4 |

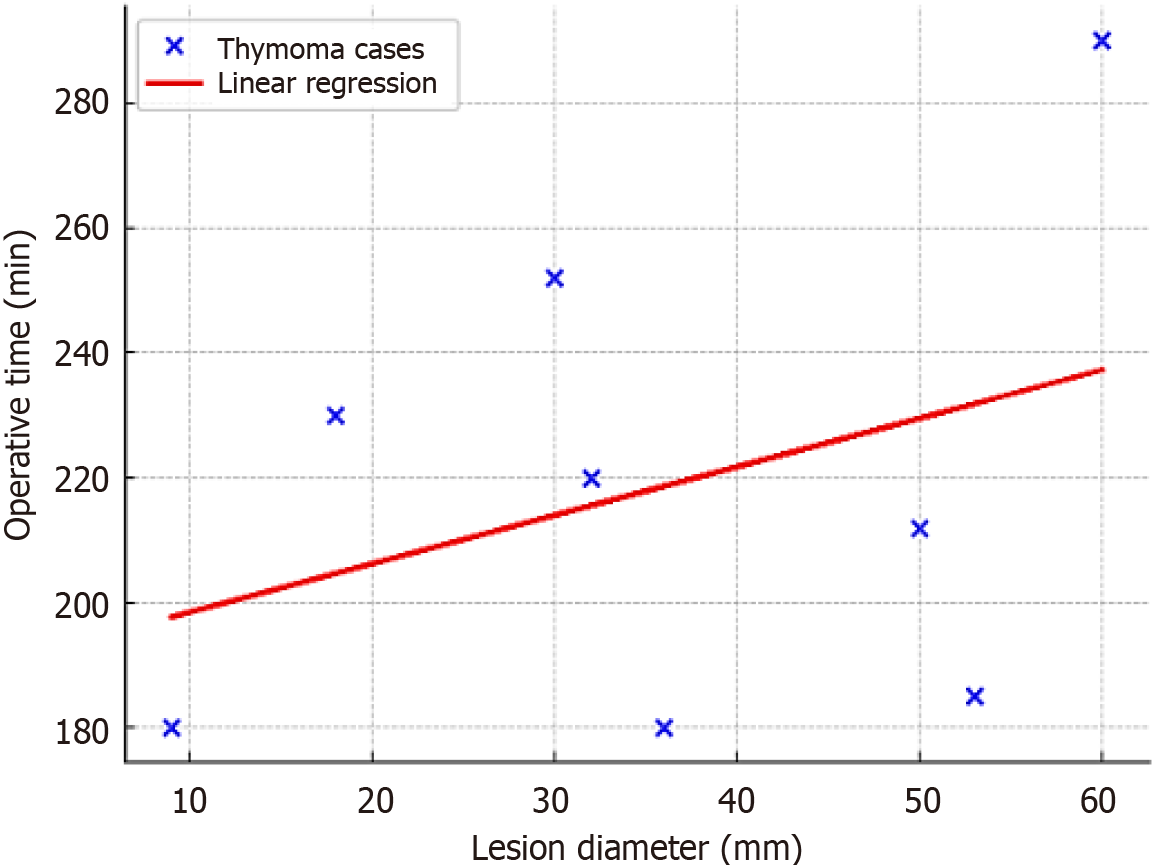

A scatterplot was created to examine the association between lesion size and surgical duration (Figure 3). Although no definitive linear correlation was observed, larger lesions generally demanded longer operative times, especially in the thymoma subgroup. This confirms that even relatively large anterior mediastinal masses can be safely resected through the subxiphoid robotic approach without significant prolongation of surgical duration.

Robotic subxiphoid thymectomy is a safe and effective method for removing lesions in the anterior mediastinum. Using a subxiphoid view along with two operative thoracic trocars, this technique achieves outstanding perioperative results, significantly reducing surgical trauma, postoperative pain, and the length of hospital stays compared to traditional sternotomy. Systematic reviews consistently show that robotic thymectomy reduces hospital stay by roughly three days and yields reduced intraoperative blood loss relative to transsternal surgery[17,18]. Our recorded median hospital stay of 3.58 ± 1.4 days aligns with these findings. Notably, no significant postoperative complications occurred within our group, highlighting the safety of this technique in appropriately selected patients.

A key advantage of the subxiphoid robotic approach is its capability to be performed without extensive OLV. Standard VATS and lateral robotic approaches usually require OLV to optimize the surgical field; however, OLV carries considerable risks, including hypoxemia, hypercapnia, barotrauma, and postoperative pulmonary complications, especially in elderly patients or those with pre-existing respiratory disease[19-22]. On the other hand, using CO2 insufflation through the subxiphoid port creates a spacious area behind the sternum while still allowing ventilation in both lungs. This approach simplifies anesthesia management, reduces risks associated with ventilation, and opens up the option for minimally invasive thymectomy to patients who might not be suitable for traditional VATS or robotic thoracic surgeries.

Compared to VATS, robotic surgery offers superior visualization, enhanced instrument dexterity, and greater precision within the anterior mediastinum. These advantages facilitate the performance of dissections near important anatomical features, such as the phrenic nerves and the innominate vein. Although systematic reviews find similar complication rates and lengths of stay between VATS and RATS, robotic techniques have demonstrated lower conversion rates to open surgery and shorter chest drainage durations in select patient series[23-27].

This method provides a clear view of both pleural cavities, facilitating the removal of thymic tissue more completely and simplifying sample extraction without the need to spread the ribs. Comparative studies have also demonstrated that robotic techniques are associated with lower postoperative pain scores and greater cosmetic satisfaction, particularly when compared to traditional sternotomy[28,29].

In our study, stratification of outcomes by histological diagnosis (Table 1) confirmed the reproducibility of the results across various subgroups. Thymomas comprised the majority of cases; however, even larger lesions, such as thymic hyperplasia, averaging 69 mm in diameter, were successfully removed within reasonable operative times. The scatterplot (Figure 2) illustrates the relationship between lesion diameter and operative time (coefficient of determination (R2 = 0.12). To assess this association quantitatively, a linear regression analysis was conducted. The resulting regression line displays a positive coefficient, indicating that operative time tends to increase as lesion size grows. This statistical finding is consistent with the visual trend observed in the graph and suggests that, although larger lesions may extend the duration of surgery, the increase remains moderate. The gentle slope of the regression line further highlights the technical feasibility of the surgical approach, even in cases involving substantial lesion dimensions. In our series, the mean operative time was 202.9 ± 44.6 minutes, consistent with previously published data on robotic thymectomy via sub

In addition to its practical feasibility, the subxiphoid approach may offer financial benefits by reducing the need for postoperative pain. However, bringing robotic systems on board comes with a hefty upfront cost and demands spe

While our findings are promising, the study’s constraints - including a small sample size, a brief follow-up period, and a single-institution design - limit the applicability of the results. To better define the role of subxiphoid RATS in clinical practice and evaluate its long-term oncologic efficacy, substantially larger, multicenter, prospective trials with prolonged follow-up are essential. Our data support the expanding body of evidence that robotic subxiphoid thymectomy is a safe and effective minimally invasive option for anterior mediastinal lesions, including sizable thymic tumors. The com

Our initial experience demonstrates that robotic subxiphoid thymectomy is both technically feasible and oncologically effective for treating anterior mediastinal lesions. It provides superior intraoperative visualization, reduces postoperative pain, and results in shorter hospital stays. The ability to avoid intercostal incisions and prolonged OLV represents a significant advantage over lateral approaches. However, limitations persist, including the small cohort size, single-center scope, and lack of long-term follow-up. Moreover, the sharp learning curve and significant costs associated with robotic platforms may impede broad adoption. Future multicenter prospective studies with larger patient populations are needed to validate the oncologic outcomes and costeffectiveness of subxiphoid RATS in thymic surgery.

| 1. | Maurizi G, D'Andrilli A, Sommella L, Venuta F, Rendina EA. Transsternal thymectomy. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2015;63:178-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Friedant AJ, Handorf EA, Su S, Scott WJ. Minimally Invasive versus Open Thymectomy for Thymic Malignancies: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Thorac Oncol. 2016;11:30-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 126] [Article Influence: 12.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Coosemans W, Lerut TE, Van Raemdonck DE. Thoracoscopic surgery: the Belgian experience. Ann Thorac Surg. 1993;56:721-730. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 59] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Suda T, Hachimaru A, Tochii D, Maeda R, Tochii S, Takagi Y. Video-assisted thoracoscopic thymectomy versus subxiphoid single-port thymectomy: initial results†. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2016;49 Suppl 1:i54-i58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Liu Y, Xu E, Kong F, Hou G, He S, Liang C, Liu Y, Li C, Shen L, Pei Y, Ren H, Guo J. Subxiphoid Thoracoscopic Surgery Is Safe and Feasible for the Treatment of Anterior Mediastinal Teratomas: A Multicentre Retrospective Study. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2025;67:ezaf267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Suda T, Kaneda S, Hachimaru A, Tochii D, Maeda R, Tochii S, Takagi Y. Thymectomy via a subxiphoid approach: single-port and robot-assisted. J Thorac Dis. 2016;8:S265-S271. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Coco D, Leanza S. Robotic thymectomy: a review of techniques and results. Kardiochir Torakochirurgia Pol. 2023;20:36-44. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | O'Sullivan KE, Kreaden US, Hebert AE, Eaton D, Redmond KC. A systematic review of robotic versus open and video assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) approaches for thymectomy. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2019;8:174-193. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Rowse PG, Roden AC, Corl FM, Allen MS, Cassivi SD, Nichols FC, Shen KR, Wigle DA, Blackmon SH. Minimally invasive thymectomy: the Mayo Clinic experience. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2015;4:519-526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Gonzalez-Rivas D, Ismail M. Subxiphoid or subcostal uniportal robotic-assisted surgery: early experimental experience. J Thorac Dis. 2019;11:231-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 6.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Wu L, Lin L, Liu M, Jiang L, Jiang G. Subxiphoid uniportal thoracoscopic extended thymectomy. J Thorac Dis. 2015;7:1658-1660. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Jiang L, Chen H, Hou Z, Qiu Y, Depypere L, Li J, He J. Subxiphoid Versus Unilateral Video-assisted Thoracoscopic Surgery Thymectomy for Thymomas: A Propensity Score Matching Analysis. Ann Thorac Surg. 2022;113:1656-1662. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Zielinski M, Czajkowski W, Gwozdz P, Nabialek T, Szlubowski A, Pankowski J. Resection of thymomas with use of the new minimally-invasive technique of extended thymectomy performed through the subxiphoid-right video-thoracoscopic approach with double elevation of the sternum. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2013;44:e113-e119; discussion e119. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | McCall P, Steven M, Shelley B. Anaesthesia for video-assisted and robotic thoracic surgery. BJA Educ. 2019;19:405-411. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Campos J, Ueda K. Update on anesthetic complications of robotic thoracic surgery. Minerva Anestesiol. 2014;80:83-88. [PubMed] |

| 16. | Mohamed A, Shehada SE, Van Brakel L, Ruhparwar A, Hochreiter M, Berger MM, Brenner T, Haddad A. Anesthetic Management during Robotic-Assisted Minimal Invasive Thymectomy Using the Da Vinci System: A Single Center Experience. J Clin Med. 2022;11:4274. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Weksler B, Tavares J, Newhook TE, Greenleaf CE, Diehl JT. Robot-assisted thymectomy is superior to transsternal thymectomy. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:261-266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kaba E, Cosgun T, Ayalp K, Toker A. Robotic thymectomy for myasthenia gravis. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2019;8:288-291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lohser J, Slinger P. Lung Injury After One-Lung Ventilation: A Review of the Pathophysiologic Mechanisms Affecting the Ventilated and the Collapsed Lung. Anesth Analg. 2015;121:302-318. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 198] [Cited by in RCA: 284] [Article Influence: 25.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Marshall MB, DeMarchi L, Emerson DA, Holzner ML. Video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery for complex mediastinal mass resections. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2015;4:509-518. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kammerer T, Speck E, von Dossow V. [Anesthesia in thoracic surgery]. Anaesthesist. 2016;65:397-412. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Shen C, Li J, Li J, Che G. Robot-assisted thoracic surgery versus video-assisted thoracic surgery for treatment of patients with thymoma: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorac Cancer. 2022;13:151-161. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Park SY, Han KN, Hong JI, Kim HK, Kim DJ, Choi YH. Subxiphoid approach for robotic single-site-assisted thymectomy. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2020;58:i34-i38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Leow OQY, Cheng C, Chao YK. Trans-subxiphoid robotic surgery for anterior mediastinal disease: an initial case series. J Thorac Dis. 2020;12:82-88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Masaoka A, Yamakawa Y, Niwa H, Fukai I, Kondo S, Kobayashi M, Fujii Y, Monden Y. Extended thymectomy for myasthenia gravis patients: a 20-year review. Ann Thorac Surg. 1996;62:853-859. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 236] [Cited by in RCA: 231] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Suda T. Single-port thymectomy using a subxiphoid approach-surgical technique. Ann Cardiothorac Surg. 2016;5:56-58. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Koliakos E, Overbeek C, Guay J, Zaouter C, Jamous JA, Nasir B, Liberman M, Abdulnour E, Ghosn P, Frigault E, Glorion M, Williams S, Ferraro P, Moore A. Intercostal cryoanalgesia for acute pain after video-assisted thoracic surgery lung resection: A randomized controlled preliminary trial. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2025;170:1242-1251.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Refai M, Gonzalez-Rivas D, Guiducci GM, Roncon A, Tiberi M, Xiumè F, Salati M, Andolfi M. Uniportal video-assisted thoracoscopic thymectomy: the glove-port with carbon dioxide insufflation. Gland Surg. 2020;9:879-885. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Murakami J, Tanaka T, Shimokawa M, Yoshimine S, Yamamoto N, Kurazumi H, Hamano K. Postoperative pain after robotic versus VATS thymectomy: a comparative cohort study. J Robot Surg. 2025;19:668. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/