Published online Nov 16, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i32.110813

Revised: July 21, 2025

Accepted: September 25, 2025

Published online: November 16, 2025

Processing time: 149 Days and 21.8 Hours

Mesonephric-like adenocarcinoma (MLA) is a rare and highly malignant disease that occurs in the uterine body or ovaries. We report a case of a MLA that was considered to have originated in the fallopian tube and presented with malignant peritonitis.

A 57-year-old female presented with a chief complaint of abdominal pain that began 2 months prior. Cancerous peritonitis was suspected. During exploratory laparoscopy, the right fallopian tube was found to be enlarged, with widespread disseminated lesions extending from the pelvic cavity to the upper abdomen. Histopathological examination of the peritoneal tissue obtained by biopsy showed tumor cells with a high nuclear/cellular ratio and proliferation of papillary tu

MLA is a very rare disease with poor prognosis. Further studies are necessary to identify effective treatment options.

Core Tip: Mesonephric-like adenocarcinoma (MLA) is a highly aggressive rare disease. There have been few reports of MLA occurring primarily in the fallopian tube. MLA is primarily diagnosed by immunohistochemical staining. We report a case of MLA originating from the fallopian tube; the patient died 1 year and 6 months after initial treatment. Effective treatment options for MLA in the fallopian tubes are urgently needed. The presence of Kirsten rat sarcoma virus mutation is a notable characteristic when considering specific treatments for MLAs.

- Citation: Sagawa S, Ito F, Nakatani M, Kurose S, Niiro E, Taniguchi M, Toyoda S, Sado T, Morita K. Mesonephric-like adenocarcinoma presenting with malignant peritonitis and suspected to originate from the fallopian tube: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(32): 110813

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i32/110813.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i32.110813

Mesonephric adenocarcinoma (MA) is a rare disease, primarily occurring in the uterine cervix, which is thought to arise from remnants or hyperplasia of the mesonephric duct. Tumors that are highly similar to MA in terms of histological, immunohistochemical, and molecular pathological features have recently been identified in the ovaries and uterine body. Notably, these tumors arise independently of mesonephric duct remnants. Such malignant tumors are defined as mesonephric-like adenocarcinoma (MLA). In the 2020 edition of the World Health Organization tumor classification for female genital tumors, MLA was newly listed under “ovarian and other tumors”[1]. In Japan, it was also added to the “Guidelines for the Management of Ovarian Cancer, No. 2 Edition” published in 2022. MLA is a very rare disease that primarily occurs in the ovaries and uterine body. MLA is most common in people in their 50s and 60s. Endometrial cancer has a poor prognosis, and even if it is discovered relatively early, there is a risk of recurrence or metastasis[2]. MLAs are diagnosed based on histological morphology and immunohistochemical staining, specifically positive GATA-binding protein 3 (GATA3), thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF1), cluster of differentiation 10 (CD10), and paired box gene-8 (PAX-8) expression, and negative for estrogen receptor (ER), progesterone receptor (PR), Wilms’ tumor 1 (WT1), and wild-type p53[1].

We report a case of primary fallopian tube MLA diagnosed via laparoscopy and treated with radical surgery.

A 57-year-old woman was referred to our hospital with suspected ovarian cancer, after experiencing more than 2 months of abdominal pain.

The patient presented to a physician with a chief complaint of abdominal pain for the past 2 months.

Unremarkable.

Unremarkable.

Abdominal bloating was observed.

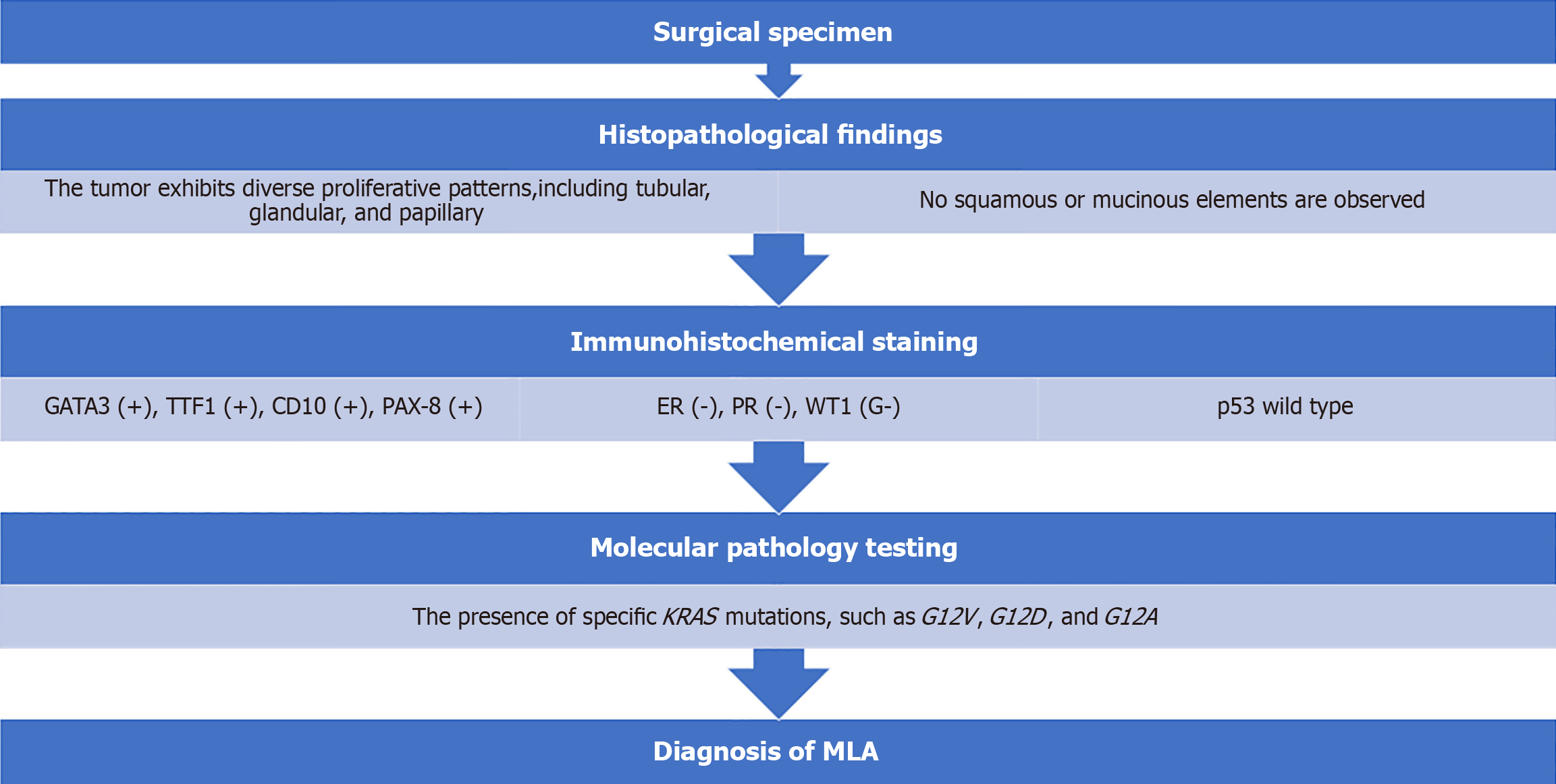

Tumor marker evaluation showed elevated antigen carbohydrate 125 Levels (86.6 U/mL). Pathological examination of the peritoneal biopsy specimen revealed tumor cells with a high nuclear/cellular ratio, accompanied by fibrosis, proliferation, finger-like or tube-like shapes (papillary tubular) and solid, irregular clusters (solid nests), with some maze-like lumina within the nests (Figure 1). Immunohistochemical examination showed positivity for GATA3, TTF1, CD10, and PAX-8 and negativity for ER, WT1, and wild-type p53, leading to a diagnosis of MLA (Figure 2).

Imaging studies revealed a 7 cm mass in the right adnexa, suggestive of diffuse peritoneal seeding extending from the pelvic cavity to the subdiaphragmatic region (Figure 3). Malignant peritonitis due to ovarian cancer was suspected, and exploratory laparoscopy was performed. Laparoscopy revealed that the right fallopian tube was enveloped by a 4 cm mass. Widespread peritoneal dissemination was observed in the omentum, paracolic gutter, Douglas’ pouch, bladder-uterine pouch, and subdiaphragmatic region (Figure 4).

MLA originating from the fallopian tube.

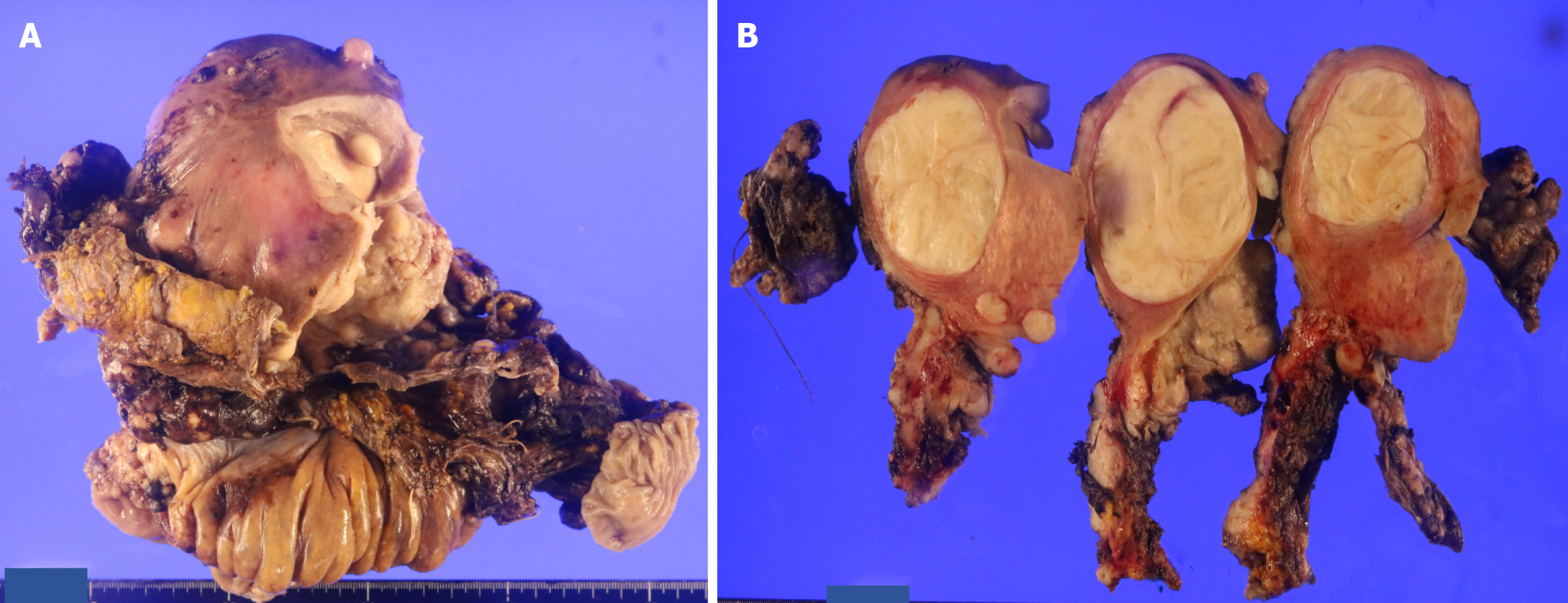

Fourteen days after the initial laparoscopic examination, the first tumor-debulking surgery was performed, including a hysterectomy with radical adnexal resection, rectal resection, total omentectomy, partial liver resection, and right diaphragmatic resection. No macroscopic residual tumors were detected during the surgery. The surgical procedure took 9 hours 21 minutes, with a blood loss of 6965 mL, requiring 16 units of packed red blood cells and 24 units of fresh frozen plasma. Ileus was observed postoperatively; however, the patient was discharged on the 28th postoperative day. Resected specimens showed tumor growth enveloping the right fallopian tube. No findings suggestive of primary tumors were identified in the cervical, uterine, or ovarian regions, indicating that the right fallopian tube was the primary tumor site (Figure 5). The pathological diagnosis was right fallopian tube MLA (International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics [FIGO] of 2014 stage IIIC, pT3cNXM0). Using the myChoice Diagnostic System®, homologous recombination deficiency was negative (gastrointestinal score 3), and genetic testing identified a Kirsten rat sarcoma virus (KRAS) G12V mutation; however, no targeted therapies based on genetic abnormalities were identified. Adjuvant chemotherapy consisted of six cycles of paclitaxel, carboplatin, and bevacizumab, followed by maintenance therapy with bevacizumab. Six months after initiating maintenance therapy, lung and liver metastasis and peritoneal dissemination were detected, and recurrence was diagnosed. A combination of doxorubicin and carboplatin was administered. However, after three cycles of administration, progression of the metastatic lesions was observed. Treatment with irinotecan monotherapy was initiated.

However, after the first dose, the patient’s general condition deteriorated, and palliative care was initiated. The patient died 1 year and 6 months after the initial treatment.

MLAs are extremely rare and clinical analyses are scarce. The largest multicenter study on MLA was conducted by Pors et al[2], who summarized the clinical and pathological characteristics of 30 cases of cervical MA, 44 of uterine MLA, and 25 of ovarian MLA. In summary, the prognosis of MA or MLA is relatively poor, with approximately 60% of cases diagnosed at an advanced stage. In the analysis of 25 cases of ovarian MLA, the mean age at diagnosis was 61 years (range, 36-81 years), with symptoms including abdominal pain (43%), abnormal bleeding (17%), abdominal distension (17%), and incidental discoveries (22%). Lymph node metastasis was present in 43% of the cases diagnosed at stage II or higher. Recurrence occurred in 42% of cases, with distant metastasis being common, and most frequently sites observed in the lungs (40%), omentum (40%), liver, bone, and peritoneum (20%). The 5-year disease-free survival rate is 68% and the 5-year overall survival rate is 71%, which are lower than those of other malignant ovarian epithelial tumors[2]. This case involved a 57-year-old female who presented with abdominal pain and was diagnosed with FIGO 2014 stage IIIC MLA. She had distant metastases, including lung and lymph node metastases, and died 1 year and 6 months after the initial treatment, indicating a poor prognosis.

The pathological findings for MLA, as described in the World Health Organization classification for ovarian MLA[1], are as follows. In terms of histopathology, MLA exhibits diverse proliferative patterns, including tubular, glandular, and papillary, and may contain eosinophilic colloid-like material within the lumina. The nuclei show dense or vesicular chromatin with inconspicuous mixed nucleoli. No squamous or mucinous elements are observed. Immunohistochemically, most cases are positive for GATA3, TTF1, CD10, and PAX-8; negative for ER, PR, and WT1; and show wild-type p53. The diagnostic criteria require the presence of typical histopathological features of MLA, and it is desirable to meet the criteria of GATA3 or TTF1 positivity and ER and PR negativity[1]. In the histopathological findings in this case, tumor cells with a high nuclear/cellular ratio and fibrotic changes proliferated and infiltrated in a papillary tubular manner, with some maze-like lumina within the nests. Immunohistochemical findings were positive for GATA3, TTF1, CD10, and PAX-8 and negative for ER, WT1, and wild-type p53, leading to a diagnosis of MLA (Figure 6). The differential diagnosis of MLA includes high-grade serous adenocarcinoma, endometriosis-associated ovarian cancer, and clear cell carcinoma. Careful differentiation is required based on histopathological findings and immunohistochemical staining results[3].

Regarding the histogenesis of MLA, during embryonic development in females, the mesonephric duct (Wolffian duct) regresses, and the paramesonephric duct (Mullerian duct) differentiates into the uterus, fallopian tubes, and upper part of the vagina. MA originating in the cervical region often exhibits remnants or hyperplasia of the mesonephric duct in the surrounding area or within the tumor, and is therefore considered to originate from the mesonephric duct. There are two theories regarding the origin of the MLA in the uterine body or adnexa: One suggests that it originates from the remnants of the mesonephric duct, whereas the other proposes that it originates from the paramesonephric duct. However, no conclusive evidence has been established[2]. MLA in the uterine body or ovaries frequently coexist with endometriosis, ovarian borderline malignant tumors, poorly differentiated serous adenocarcinoma, endometrioid carcinoma, and clear-cell carcinoma, among other Müllerian tumors. Reports indicate that coexisting tumors share the same genetic origin, leading to an increasing view that they originate from the paramesonephric duct[4]. To the best of our knowledge, the only reported case of MLA originating from the fallopian tube is that reported by Xie et al[5], which was considered to originate from the mesonephric duct. Assuming a mesonephric duct origin, residual structures of the mesonephric duct around the fallopian tube, such as the cystic appendage or the infundibular duct, could serve as the site of origin. The histopathological findings in this case showed that the tumor primarily involved the peritubal tissue and developed in a manner that involved the normal tubal epithelium, suggesting a possible origin from the infundibular tube, leading us to consider it to be mesonephric duct-derived. No concomitant endometriosis or Müllerian carcinoma was identified.

For the initial treatment of ovarian MLA, many reports have described performing debulking surgery followed by adjuvant chemotherapy with paclitaxel plus carboplatin therapy for 4-8 cycles[3,6-8]. In patients with FIGO stage III or IV disease, some received chemotherapy prior to surgery. While treatment generally follows the guidelines for ovarian cancer, some cases have reported recurrence without chemotherapy in patients with FIGO stage IA[3,8], suggesting that adjuvant chemotherapy may be necessary regardless of the disease stage. Yang et al[6] reported that tumors are more likely to metastasize when they have a diameter of > 4 cm, unclear tumor boundary, relatively high clinical stage (III-IV), large areas of necrosis, high nuclear fission index (> 10/10 high-power field), and lymphovascular invasion. Because MLA has a high recurrence rate, follow-up similar to that for similar high-grade tumors may be recommended. Few studies have investigated the efficacy of chemotherapy for recurrent MLAs. In cases of recurrent MLA after paclitaxel and carboplatin therapy, treatment with a combination of gemcitabine and carboplatin resulted in disease control without recurrence[7]. In contrast, Koh et al[3] reported that patients with recurrent MLA who underwent tumor resection surgery followed by postoperative chemotherapy experienced disease progression and died within 2 years of recurrence. The treatment course for recurrent MLA is poorly documented, and standardized treatment and effective outcomes remain unclear. The presence of KRAS gene mutations is a notable characteristic when considering the specific treatments for MLAs. Ogawa et al[8] and Koh et al[3] reported the presence of specific KRAS gene mutations, such as G12V, G12D, and G12A. In the present case, a KRAS G12V mutation was identified. KRAS mutations have been suggested as potential treatment targets for MLA and have been approved for use in Japan for patients with unresectable advanced or recurrent non-small cell lung cancer with KRAS G12C mutations; its clinical application is also progressing in colorectal and pancreatic cancers[9]. The development of new drugs targeting KRAS mutations as therapeutic targets for MLA is also considered a possibility.

Here, we report a case of MLA that was primary to the fallopian tube. This is a rare disease with poor prognosis, so further research with more cases is needed to identify effective treatments.

| 1. | World Health Organization. Mesonephric-like adenocarcinoma. [cited 3 May 2025]. Available from: https://whobluebooks.iarc.who.int/structures/female-genital-tumours/. |

| 2. | Pors J, Segura S, Chiu DS, Almadani N, Ren H, Fix DJ, Howitt BE, Kolin D, McCluggage WG, Mirkovic J, Gilks B, Park KJ, Hoang L. Clinicopathologic Characteristics of Mesonephric Adenocarcinomas and Mesonephric-like Adenocarcinomas in the Gynecologic Tract: A Multi-institutional Study. Am J Surg Pathol. 2021;45:498-506. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 51] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 21.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Koh HH, Park E, Kim HS. Mesonephric-like Adenocarcinoma of the Ovary: Clinicopathological and Molecular Characteristics. Diagnostics (Basel). 2022;12:326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Tanaka R, Kimura K, Nishi S, Ikeda K, Wakui Y, Kiuchi S. A case of ovarian mesonephric-like adenocarcinoma diagnosed after laparoscopic surgery. J Med KKR Sapporo Med Cent. 2021;18:46-49. |

| 5. | Xie C, Shen YM, Chen QH, Bian C. Primary mesonephric adenocarcinoma of the fallopian tube: A case report. World J Clin Cases. 2021;9:4741-4747. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Yang Y, Zhao M, Jia Q, Tang H, Xing T, Li Y, Tang B, Xu L, Wei W, Zheng H, Shi R, Xia B, Chen J. Mesonephric-like adenocarcinoma of the ovary. J Ovarian Res. 2024;17:57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Xie C, Chen Q, Shen Y. Mesonephric adenocarcinomas in female genital tract: A case series. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100:e27174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Ogawa A, Yoshida H, Kawano S, Kikkawa N, Kobayashi-Kato M, Tanase Y, Uno M, Ishikawa M. Ovarian Mesonephric-like Adenocarcinoma: Its Prevalence in a Japanese High-Volume Cancer Center and a Literature Review on Therapeutic Targets. Curr Oncol. 2024;31:5107-5120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Hong DS, Fakih MG, Strickler JH, Desai J, Durm GA, Shapiro GI, Falchook GS, Price TJ, Sacher A, Denlinger CS, Bang YJ, Dy GK, Krauss JC, Kuboki Y, Kuo JC, Coveler AL, Park K, Kim TW, Barlesi F, Munster PN, Ramalingam SS, Burns TF, Meric-Bernstam F, Henary H, Ngang J, Ngarmchamnanrith G, Kim J, Houk BE, Canon J, Lipford JR, Friberg G, Lito P, Govindan R, Li BT. KRAS(G12C) Inhibition with Sotorasib in Advanced Solid Tumors. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1207-1217. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1267] [Cited by in RCA: 1310] [Article Influence: 218.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/