Published online Oct 26, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i30.110475

Revised: July 8, 2025

Accepted: August 25, 2025

Published online: October 26, 2025

Processing time: 126 Days and 19.6 Hours

This case report enhances the medical literature by presenting a rare instance of primary esophageal mucoepidermoid carcinoma (MEC), highlighting its unique histological features and the challenges in diagnosis that can arise due to its similarities with other esophageal cancers.

A 58-year-old female presented with dysphagia and was initially misdiagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma. Upon further evaluation, upper gastrointestinal endoscopy revealed a 1.5 cm lesion in the distal esophagus. The patient under

Awareness of MEC is essential for accurate diagnosis and management due to its rarity and potential for misdiagnosis.

Core Tip: Primary esophageal mucoepidermoid carcinoma is an uncommon malignancy distinguished by its unique mixture of epidermoid, intermediate, and mucous cells. Due to its similarities with squamous cell carcinoma and adenosquamous carcinoma, it is frequently misdiagnosed, leading to challenges in clinical management. This case emphasizes the need for stricter diagnostic procedures, such as immunohistochemical analyses, and greater awareness in order to guarantee an accurate diagnosis. To improve patient care and establish efficient management plans for this uncommon tumor, additional research and cooperative efforts are desperately needed, as evidenced by the absence of established treatment guidelines.

- Citation: Yolburun SB, Gunizi OC, Elpek GO. Insights from literature of esophageal mucoepidermoid carcinoma in a female: A rare case report. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(30): 110475

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i30/110475.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i30.110475

Primary esophageal mucoepidermoid carcinoma (MEC) is a rare and malignant epithelial tumor characterized by a unique composition of epidermoid, intermediate, and mucous cells. Although its exact origin is unknown, it is thought to originate from the esophageal submucosal glandular tissues. According to the 2022 World Health Organization classification, MEC is categorized separately alongside esophageal adenosquamous carcinoma due to its unclear pathogenesis and limited treatment protocols and prognostic data[1,2].

MEC accounts for less than 1% of all esophageal cancers, making it a much rarer tumor compared to other more common esophageal malignancies, such as squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) and adenocarcinoma[3]. This rarity often leads to misdiagnosis during endoscopic biopsies, which can severely impact the selection of appropriate preoperative treatment options[4]. The current literature is limited, with a small number of case reports and studies encompassing the clinical features, therapies, and outcomes of MEC, which adds to the challenges that medical professionals face in managing this disorder[5].

A correct understanding of differential diagnosis is essential due to the significant overlap in histological features among adenosquamous carcinoma, SCC, and MEC. The definitive diagnosis is often established post-surgery, demo

This report aims to enhance awareness of the differential diagnosis of esophageal tumors by presenting a case of primary esophageal MEC and comparing its clinical and histopathological findings with those documented in the existing literature.

A 58-year-old female presented to an external center with complaints of dysphagia, a common symptom associated with esophageal tumors[3].

The patient reported symptoms having commenced 8 weeks before the first hospital admission.

Apart from a prior diagnosis of chronic gastritis with intestinal metaplasia and linear neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia, the patient had no significant medical history.

The patient claimed no family history of malignant tumors.

Medical evaluation revealed normal vital signs, including a body temperature of 36.5 °C, blood pressure of 116/70 mmHg, heart rate of 78 beats per min, and respiratory rate of 18 breaths per minute.

Serum cancer indicators were slightly elevated, as shown by carbohydrate antigen 19-9 at 45 U/mL (normal range: 0-37 U/mL) and carcinoembryonic antigen of 3.8 ng/mL (normal range: 0-2.5 ng/mL). Routine blood and urine evaluation indicated no unusual findings.

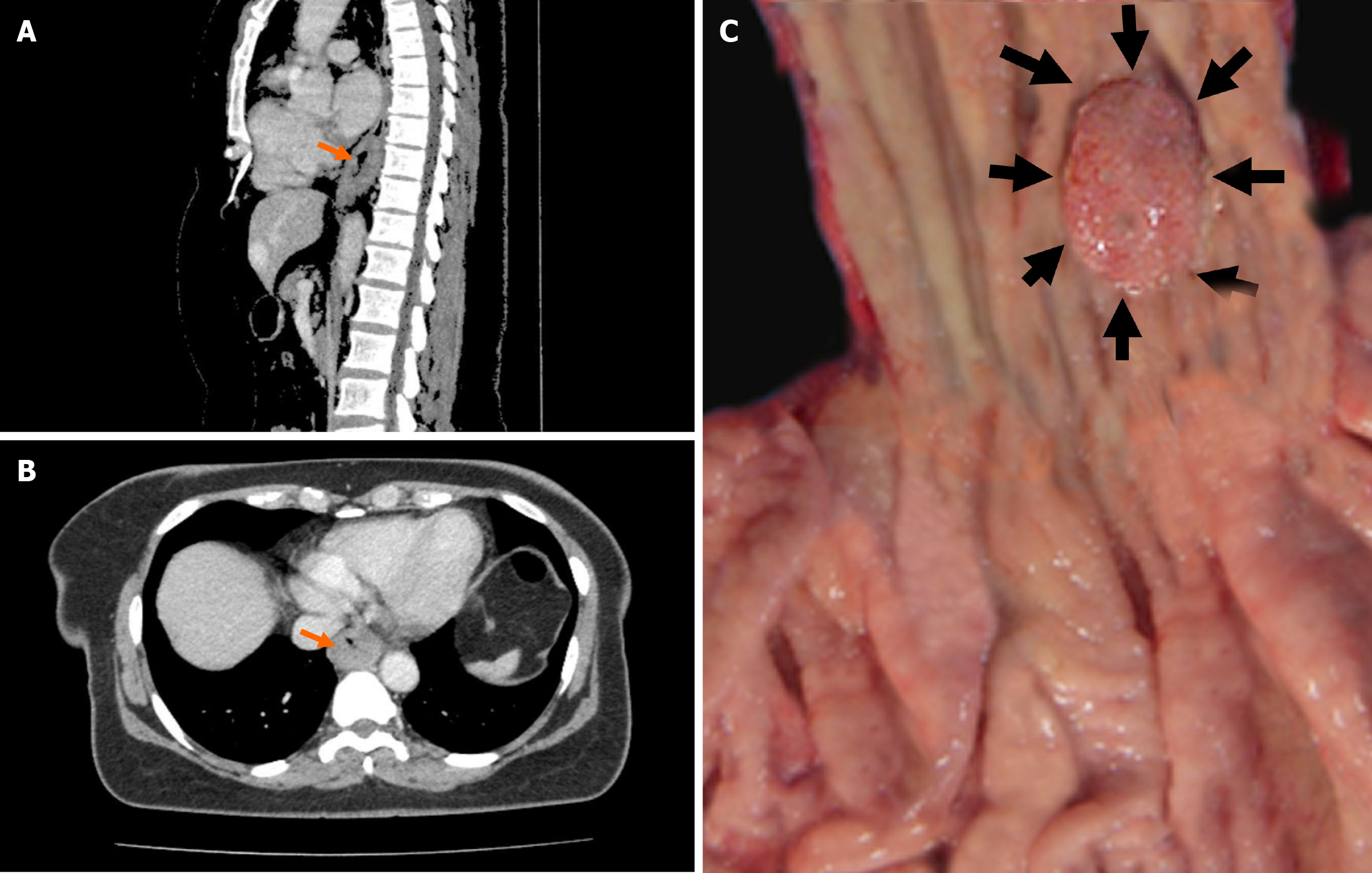

Given the high incidence of dysphagia in patients with esophageal cancer, a thorough evaluation was warranted. Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy revealed a small and localized mass in the distal esophagus, prompting biopsies for further assessment. Pathological examination initially confirmed a diagnosis of SCC, leading the patient to be referred to the General Surgery Department of Akdeniz University Medical Faculty (Antalya, Türkiye). Contrast enhanced computed tomography (CECT) of the thorax and abdomen showed no lymph node metastasis, which contributed to the decision to forgo neoadjuvant therapy[6]. However, the CECT thorax did reveal wall thickening, providing important insight into the tumor's characteristics (Figure 1A and B). While neoadjuvant therapy can be beneficial for certain patients with esophageal cancers, in the present case, the endoscopic findings of the tumor (including small size, localized mass, and the overall health of the patient) led the surgical team to proceed directly to resection without administering preoperative treatment. The patient underwent partial esophagectomy and partial gastrectomy, and tissue samples were sent for further assessment. During the reconstructive phase, a gastric conduit was fashioned from the stomach, ensuring it had a robust blood supply by preserving the right gastroepiploic artery. This conduit was then carefully brought up to the thoracic cavity to perform a gastroesophageal anastomosis, reconnecting the gastrointestinal tract. Post-surgery, we focused on monitoring for any complications and providing nutritional support until the patient could safely resume normal swallowing.

Macroscopic examination revealed a firm, pale, 1.5 cm × 1 cm lesion located in the distal esophagus at 0.5 cm from the gastroesophageal junction (Figure 1C). The entire lesion was excised, and histological evaluation of serial sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin revealed tumor tissue invading the muscular layer and extending into the adventitia, with islands containing squamous cells and mucin-producing glandular structures. Notably, perineural invasion was present, but lymphovascular invasion was not observed. Eight regional lymph nodes were dissected, all of which showed reactive hyperplasia. No metastatic lymph nodes were identified. The immunohistochemical markers p63, p40, carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), cytokeratin (CK) 19, mucin (MUC) 1, MUC4, and CK8 were utilized for definitive diagnosis. P40 and p63 showed nuclear positivity in squamous cells, whereas CK8 and CK19 showed positivity in glandular cells. CEA demonstrated luminal positivity, and MUC1 and MUC4 exhibited focal cytoplasmic positivity. Histochemical MUC positivity was also noted. The Ki67 proliferative index was 15% (Figure 1).

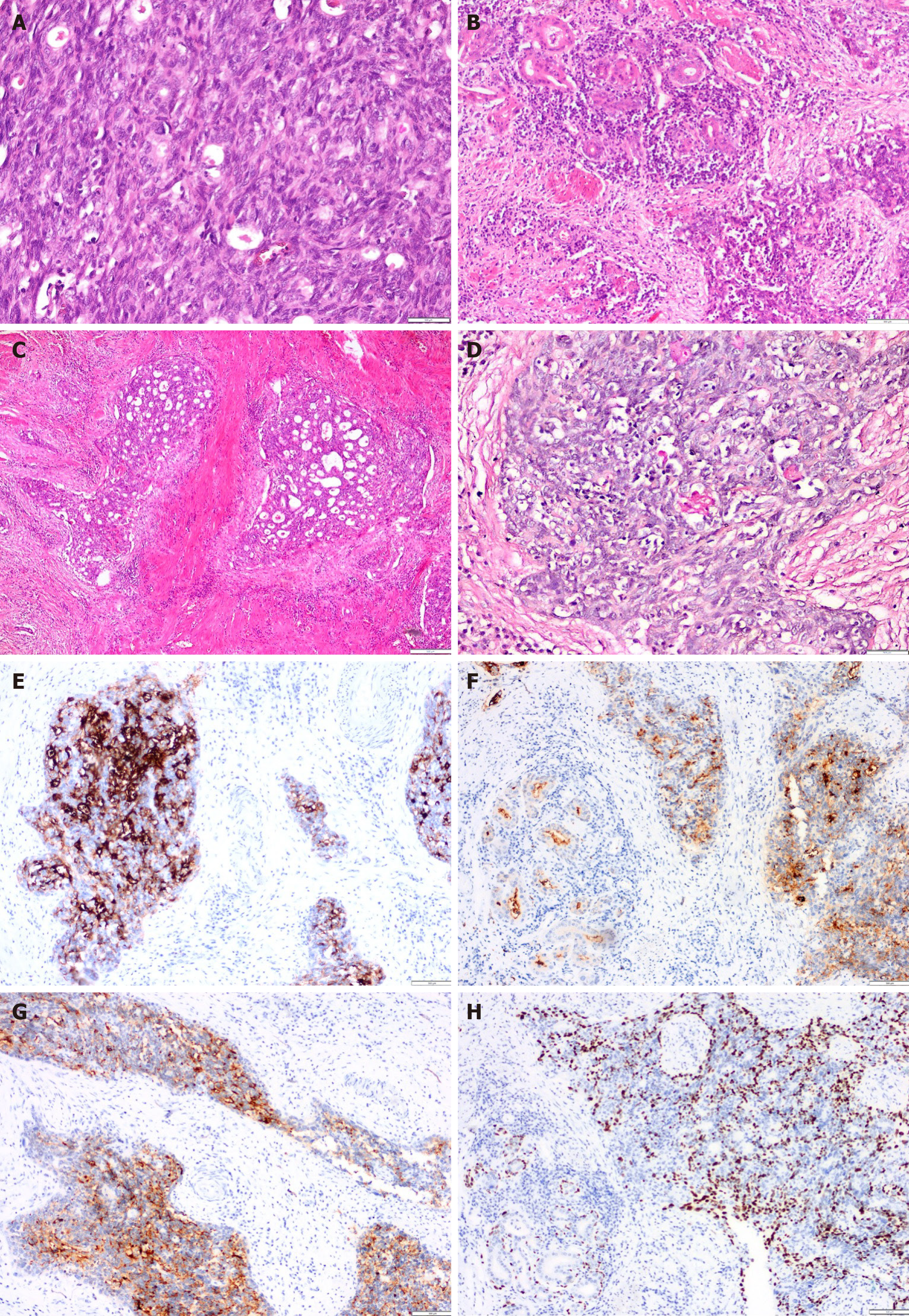

Macroscopic examination revealed a firm, pale, 1.5 cm × 1 cm lesion located in the distal esophagus at 0.5 cm from the gastroesophageal junction (Figure 1C). The entire lesion was excised, and histological evaluation of serial sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin revealed tumor tissue invading the muscular layer and extending into the adventitia, with islands containing squamous cells and mucin-producing glandular structures. Notably, perineural invasion was present, but lymphovascular invasion was not observed. Eight regional lymph nodes were dissected, all of which showed reactive hyperplasia. No metastatic lymph nodes were identified. The immunohistochemical markers p63, p40, CEA, CK 19, MUC 1, MUC4, and CK8 were utilized for definitive diagnosis. P40 and p63 showed nuclear positivity in squamous cells, whereas CK8 and CK19 showed positivity in glandular cells. CEA demonstrated luminal positivity, and MUC1 and MUC4 exhibited focal cytoplasmic positivity. Histochemical MUC positivity was also noted. The Ki67 proliferative index was 15% (Figure 2).

Based on these findings, the patient was diagnosed with primary esophageal MEC. Importantly, no tumor tissues were found at the surgical margins. The case was classified as pT3pN0pM0, Stage IIb.

Following the operation, the patient recovered uneventfully and was discharged on postoperative day 7.

The patient remains alive after 15 months of follow-up without receipt of postoperative radiotherapy or chemotherapy.

Primary esophageal MEC is a rare malignancy, often misdiagnosed due to its unique histological features. The average age at diagnosis is reported to be about 58 years[3]. In a comprehensive review of the literature on MEC, a search of PubMed using terms such as "mucoepidermoid carcinoma" and "esophageal mucoepidermoid carcinoma" reveals varying demographics (Table 1). Retrospective studies conducted by Fegelman et al[3], Lieberman et al[5], and others indicate a higher prevalence of male patients, with male-to-female ratios ranging from 64% to 100%[1]. The combined data from these studies show that 75.5% of the patients were male and 24.4% were female[4]. Our case, involving a female patient, contributes to the literature highlighting sex variations in MEC, suggesting that further exploration into the underlying biological mechanisms may be warranted.

| Ref. | n | Sex | Age in years | Localization | Symptoms | Treatment | Size in cm | IHC | Molecular findings | |||

| Male | Female | Upper | Middle | Lower | ||||||||

| Ozawa et al[18] | 2 | 2 | - | 61 | 0 | 1 | 1 | Dysphagia and metastasis | - | 6 | - | - |

| Fegelman et al[3] | 18 | 18 | 2 | 65.7 | 2 | 11 | 5 | Dysphagia | - | 6.1 | - | - |

| Lieberman et al[5] | 14 | 9 | 5 | 60 | 1 | 5 | 8 | Dysphagia | - | - | - | - |

| Batoon et al[19] | 1 | 1 | - | 80 | 0 | 0 | 1 | Dysphagia | - | 6 | - | - |

| Hagiwara et al[4] | 8 | 8 | - | 58 | 1 | 4 | 3 | Dysphagia | Esophagectomy 2 preop-RT & CT | - | PCNA, CEA | - |

| Tamura et al[6] | 1 | 1 | - | 67 | 0 | 1 | 0 | - | EMR | - | CEA | - |

| Turkyilmaz et al[20] | 1 | - | 1 | 82 | 0 | 1 | 0 | Dysphagia | Esophagectomy | 2 | - | - |

| Chen et al[21] | 36 | 27 | 9 | 58 | 0 | 30 | 6 | Dysphagia, weight loss, retrosternal pain | Esophagectomy | 5 | - | |

| Kiyozaki et al[22] | 1 | - | 1 | 67 | 0 | 1 | 0 | - | Esophagectomy | 1.5 | - | - |

| Wang et al[7] | 58 | 36 | 22 | 59 | 10 | 39 | 9 | - | - | 5 | - | - |

| Chen et al[2] | 1 | 1 | - | 52 | 1 | 0 | 0 | Dysphagia | Esophagectomy | 1 | AE1/AE3, CK5/6, CK7, CK18, p40, p63 | MAML2 rearrangement |

| Jeun et al[23] | 1 | - | 1 | 63 | 0 | 1 | 0 | - | EMR | 6 | - | - |

| Wang et al[1] | 48 | 42 | 6 | 63 | 3 | 34 | 11 | - | - | 5 | p63, CEA, CK, PSA, CK5/6, CK7 | - |

| Osama et al[8] | 1 | - | 1 | 58 | 0 | 0 | 1 | - | Esophagectomy | - | - | FISH, Absence of MAML2 rearrangement |

| Total | 101 | 117 | 17 | 62.5 | 18 | 72 | 38 | - | - | - | - | - |

| Present case | 1 | - | 1 | 58 | 0 | 0 | 1 | Dysphagia | Esophagectomy | 1.5 | p63, p40, CEA, CK19, MUC1, MUC4, CK8 | - |

Dysphagia remains the most common presenting symptom, observed in 92.8% of patients in the existing literature[4,5]. Only 1 patient reported gastric pain, and another presented with a neck mass[3,6]. Our patient presented with dysphagia, aligning with these findings, further emphasizing the need for awareness of this symptom among clinicians.

Regarding tumor location, studies by Lieberman et al[5] found that the most common site for MEC was the lower esophagus (54%), while others indicated the middle esophagus as the predominant site[2]. Our case involved a tumor located in the lower esophagus, which is significant given the reported distribution of tumor locations. This highlights the variability in tumor localization and the necessity for thorough examinations in patients presenting with esophageal symptoms.

In terms of tumor size, the literature reports an average diameter of 4.8 cm for MEC[3]. By contrast, the patient in our case study presented with a tumor size of 1.5 cm, which may reflect the tumor's location and the severity of symptoms influencing the timing of presentation. The macroscopic features of esophageal MEC have been classified into various types including medullary (49%), ulcerative (21.8%), sclerotic (12.7%), indurated (10.9%), and solid (1.8%)[2]. Our case aligns with the solid mass category, which may be indicative of its unique pathophysiology (Figure 2).

The preoperative diagnostic rate for MEC is alarmingly low worldwide. In our case, the biopsy mistakenly identified the lesion as SCC, with the definitive diagnosis established only after surgical resection. According to Wang et al[7], among 58 cases of MEC, only 1 was correctly diagnosed preoperatively by endoscopic biopsy, whereas 43 were misdiagnosed as SCC, 2 as adenosquamous carcinoma, and 1 as adenocarcinoma. This highlights the pressing need for improved diagnostic accuracy in preoperative evaluations, as noted by other researchers[4].

Differential diagnosis commonly involves adenosquamous carcinoma and SCC (Table 2). The composition of MEC includes a mixed population of epidermoid, intermediate, and mucous cells, as opposed to the primarily squamous composition of SCC and the distinct components in adenosquamous carcinoma. The cellular arrangement in MEC shows intermixed squamous and mucinous cells, while SCC predominantly exhibits keratinization and intercellular bridges. In contrast, adenosquamous carcinoma is characterized by separate squamous and glandular components, emphasizing the complexity of its histological architecture[2]. Key features aiding in diagnosing MEC include mild atypia, rare mitotic figures, a low Ki-67 index, and intracellular mucin[2].

| Characteristic | Mucoepidermoid carcinoma | Squamous cell carcinoma | Adenosquamous carcinoma |

| Composition | Mixed composition of epidermoid, intermediate, and mucous cells[2] | Primarily composed of squamous cells[3] | Distinct squamous and adenocarcinoma components[8] |

| Cellular arrangement | Squamous and mucinous cells intermixed[1] | Predominantly shows keratinization and intercellular bridges[4] | Separate squamous and glandular components[5] |

| Nuclear features | Mild atypia with rare mitotic figures[2] | High nuclear pleomorphism and increased mitotic activity[7] | Variable nuclear features depending on cell type[3] |

| Mucin production | Mucin-producing glandular structures present[5] | Minimal to no mucin production[4] | Some mucin production possible, but less than MEC[1] |

| IHC markers | Positive for p63, p40, CEA, CK19, MUC1, MUC4, CK8[1] | Positive for p63, p40, may show keratinization[8] | Positive for CK7 and CEA; p63 may be positive[4] |

| Surface dysplasia | Typically absent; no surface dysplasia observed[3] | Surface dysplasia is commonly present[5] | Dysplasia may be present in adenocarcinoma components[8] |

| Diagnosis confirmation | Often requires surgical resection for definitive diagnosis; FISH analysis may be beneficial for MAML2 rearrangement[2] | Diagnosed via biopsy; histological features confirm diagnosis[4] | Diagnosis made by identifying distinct components[7] |

In 2003, Hagiwara et al[4] demonstrated the significance of proliferating cell nuclear antigen and CEA staining in diagnosing MEC. More recently, Wang et al[1] reported positive immunohistochemical markers such as prostate-specific antigen, p63, CEA, CK5/6, and CK7 in a series of 48 cases, which adds to the diagnostic criteria for MEC. Our patient exhibited a profile consistent with these findings, showing positivity for p63, p40, CEA, CK19, MUC1, MUC4, and CK8, which aligns with previously published data (Table 2). This immunohistochemical profile reinforces the need for a comprehensive approach to diagnosing MEC, as it highlights the unique cellular characteristics that differentiate it from other esophageal malignancies.

Recent advances in molecular genetics have also contributed to our understanding of MEC. Chen et al[2] first demonstrated mastermind-like transcriptional coactivator 2 (MAML2) rearrangement using fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH) in a case of MEC, suggesting its potential as a molecular marker for diagnosis. MAML2 gene rearrangement can serve as objective confirmation of MEC diagnosis, particularly in cases where histological morphology is ambiguous and not easily distinguishable from adenosquamous carcinoma. Conversely, Osama et al[8] reported a rare case of MAML2-negative esophageal MEC, emphasizing that while genetic markers can aid in diagnosis, they are not always definitive. In our case, FISH analysis was not performed due to the presence of sufficient tumor tissue and clear diagnostic criteria from histopathological and immunohistochemical evaluations. Considering all of these data, incorporating molecular testing into routine diagnostic protocols for MEC may enhance diagnostic accuracy and provide further insights into tumor behavior and treatment responses.

Some high-grade MECs can present challenges due to increased nuclear pleomorphism, mitotic activity, and cellular necrosis, which may lead to confusion with SCC, as noted by Osama et al[8]. The presence of dysplasia in the surface epithelium typically favors a diagnosis of SCC, while its absence suggests MEC but does not definitively rule out SCC, according to Mewa Kinoo et al[9]. In our case, no surface epithelium dysplasia was observed. Furthermore, immunohistochemical analysis specifically highlighted squamous cells that did not exhibit keratinization or keratin pearls, consistent with findings from Wang et al[1].

In the presented case, the patient had been misdiagnosed with SCC of the esophagus at an external center, demonstrating the importance of recognizing the potential for misdiagnosis in high-grade tumors. High-grade MECs can lead to diagnostic errors due to their overlapping histological features with SCC. The lack of observed surface epithelial dysplasia should have prompted further investigation for MEC, illustrating the diagnostic challenges in high-grade tumors and the necessity to consider alternative diagnoses when faced with unclear histological characteristics in esophageal biopsies. Additionally, this finding may not be observed in inadequate and small tissue samples, leading to incorrect diagnoses, similar to the case presented here. Consequently, obtaining multiple biopsies from different areas during endoscopic evaluation can provide a wider range of cellular features, ultimately facilitating diagnosis. Thus, the absence of surface epithelium dysplasia, combined with specific immunohistochemical findings, can guide pathologists toward a correct diagnosis of MEC, in biopsies. This case serves as a reminder of the critical need for careful evaluation and consideration of multiple tumor types of the esophagus in unclear situations to avoid misdiagnosis and ensure appropriate patient management.

According to recent data on MEC, 81% of cases were classified as T3-T4, while 19% were classified as T1-T2. Regional lymph node involvement was noted in 74.1% of patients classified as N0, while 25.9% were classified as N1-N3[7]. Our patient was classified as T3 N0, Stage II, suggesting a more favorable prognosis given the absence of lymph node involvement. The differentiation of tumors is crucial for prognosis, with recent data indicating that 48.3% of cases were classified as G2, 29.3% as G1, and 22.4% as G3[7]. In our case, due to the lack of differentiation criteria mentioned in the College of American Pathologists protocol, the tumor was not categorized by grade. This lack of standardization in grading MEC highlights the need for clearer guidelines and criteria to assist pathologists in their evaluations.

The average follow-up duration for patients after treatment was reported to be approximately 18.4 months, with a concerning 67.9% mortality rate[5]. By contrast, our patient remains alive 5 months post-surgery, indicating the importance of ongoing monitoring and individualized patient care.

The treatment of esophageal MEC remains uncertain, with no standardized approach available. A review of the literature revealed that 63.9% of patients were treated surgically, while 16.4% received additional radiotherapy and 13.4% received chemotherapy[4].

Some studies have found no significant effect of postoperative radiotherapy on survival[7]. The choice to withhold adjuvant therapy in our case reflects a cautious strategy, considering the absence of clear survival benefits as reported in various studies. This approach aligns with the current understanding that the role of adjuvant therapy in MEC is not well-established, necessitating an individualized treatment plan based on the tumor characteristics and the overall health of the patient. Moreover, in this case, the decision to proceed directly to surgical intervention without neoadjuvant therapy was influenced by multiple compelling factors. First and foremost, our patient's strong preference for immediate surgery played a crucial role. According to the 2022 ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines, patient preferences and performance status are critical considerations in the management of locally advanced esophageal cancer, emphasizing the importance of aligning treatment strategies with patient wishes and clinical status[10]. Furthermore, imaging data provided important information; the lack of lymph node metastases (N0 status) suggested a more localized disease, making primary surgery a viable option. According to recent research, prompt surgical intervention is a prudent course of action for T3N0M0 patients with distinct surgical margins[11]. This approach aligns with the current understanding that the role of adjuvant therapy in MEC is not well-established, necessitating an individualized treatment plan based on the tumor characteristics and the overall health of the patient.

The decision to perform surgical resection, including partial gastrectomy, in the management of primary esophageal mucoepidermoid carcinoma was guided by several key considerations that align with current oncological and surgical best practices. Given the tumor's proximity to the gastroesophageal junction, achieving negative margins was a priority, necessitating a more extensive resection approach. This is particularly important in esophageal cancers, where local recurrence can significantly impact survival outcomes[11,12].

Current guidelines emphasize that in cases where tumors are located near the gastroesophageal junction, surgical strategies should aim to ensure complete tumor resection while minimizing the risk of local recurrence[10]. The inclusion of partial gastrectomy, although seemingly extensive for a 1.5 cm tumor, is supported by the literature, which highlights its role in enhancing surgical margins, particularly when tumors are located near critical anatomical junctions[13]. Moreover, the surgical approach was tailored to preserve esophageal and gastric function, utilizing reconstruction techniques such as esophagogastrostomy to maintain the patient's quality of life post-surgery[14].

Additionally, recent studies suggest that in cases of esophageal cancer, the choice of surgical resection should not solely be based on tumor size but also its location and the potential impact on vital structures[15]. This approach aligns with findings from a recent study, which indicated that comprehensive surgical resection, including adjacent structures when necessary, can improve outcomes in terms of both survival and recurrence rates[16]. By opting for this method, the surgical team ensured that the patient received a treatment plan that was both thorough and aligned with evidence-based practices.

Additionally, the clinical urgency of the patient's symptoms, such as dysphagia, necessitated rapid surgical management to prevent potential complications. The NCCN Guidelines for 2024 emphasize that in emergencies, immediate surgery may be prioritized over neoadjuvant therapy[17]. Moreover, recent evidence from a 2024 meta-analysis advocates for a tailored treatment strategy, particularly in cases where patients decline multimodal therapy or present with frail health conditions[16]. While neoadjuvant therapy remains a standard recommendation, this case exemplifies the need for flexibility and personalization in treatment approaches, ensuring that decisions are patient-centered and evidence-informed. This comprehensive strategy addresses the immediate clinical needs and aligns with the latest oncological practices

The absence of a standardized treatment protocol underscores the need for further clinical studies to determine the most effective management strategies for this rare malignancy. Given the rarity of MEC and the limited number of cases reported, there is a critical need for multicenter studies that can provide comprehensive data on treatment outcomes, prognostic factors, and potential biomarkers that could guide therapy. This collaborative research could facilitate the development of evidence-based guidelines for the management of MEC.

This study was limited by the small number of reported cases of primary esophageal MEC in the existing literature, which restricts the ability to draw broader conclusions regarding its epidemiology and clinical outcomes. Additionally, the variability in diagnostic techniques and treatment protocols among different institutions may affect the consistency of reported findings. The absence of standardized grading criteria for MEC further complicates the interpretation of results and may hinder the establishment of universally accepted treatment guidelines. Ultimately, future multicenter studies with larger cohorts are needed to provide more definitive insights into the management of this rare malignancy.

In conclusion, primary esophageal MEC is a rare and multifaceted malignancy that poses significant diagnostic and therapeutic challenges. Increased awareness among clinicians, implementation of advanced diagnostic techniques, and development of standardized treatment protocols are each essential for improving patient outcomes. Ongoing research into both the molecular characteristics of and optimal management strategies for MEC will be crucial in advancing care for patients affected by this complex disease. Collaborative efforts across institutions will foster the accumulation of data necessary to refine treatment approaches and ultimately enhance survival rates for this patient population.

| 1. | Wang Y, Wu Y, Zheng C, Li Q, Jiao W, Wang J, Xiao L, Pang Q, Zhang W, Wang J. Clinico-pathological study of esophageal mucoepidermoid carcinoma: a 10-year survival from a single center. BMC Gastroenterol. 2024;24:156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Chen R, Wang B, Li L, Xue L. Mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the esophagus with MAML2 gene rearrangement: Case report and literature review. Pathol Res Pract. 2023;241:154242. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Fegelman E, Law SY, Fok M, Lam KY, Loke SL, Ma LT, Wong J. Squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus with mucin-secreting component. Mucoepidermoid carcinoma. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1994;107:62-67. [PubMed] |

| 4. | Hagiwara N, Tajiri T, Tajiri T, Miyashita M, Sasajima K, Makino H, Matsutani T, Tsuchiya Y, Takubo K, Yamashita K. Biological behavior of mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the esophagus. J Nippon Med Sch. 2003;70:401-407. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lieberman MD, Franceschi D, Marsan B, Burt M. Esophageal carcinoma. The unusual variants. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1994;108:1138-1146. [PubMed] |

| 6. | Tamura S, Kobayashi K, Seki Y, Matsuyama J, Kagara N, Ukei T, Uemura Y, Miyauchi K, Kaneko T. Mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the esophagus treated by endoscopic mucosal resection. Dis Esophagus. 2003;16:265-267. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Wang X, Chen YP, Chen SB. Esophageal Mucoepidermoid Carcinoma: A Review of 58 Cases. Front Oncol. 2022;12:836352. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Osama MA, Sharma S, Chatterjee P, Mittal A, Andley M, Kakkar A. Shining Light on Rarity: Mucoepidermoid Carcinoma of the Esophagus with Absence of MAML2 Gene Rearrangement. Indian J Surg Oncol. 2024;15:374-378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Mewa Kinoo S, Maharaj K, Singh B, Govender M, Ramdial PK. Primary esophageal sclerosing mucoepidermoid carcinoma with "tissue eosinophilia". World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:7055-7060. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Lordick F, Mariette C, Haustermans K, Obermannová R, Arnold D; ESMO Guidelines Committee. Oesophageal cancer: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2016;27:v50-v57. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 523] [Cited by in RCA: 690] [Article Influence: 69.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Thakur B, Devkota M, Chaudhary M. Management of Locally Advanced Esophageal Cancer. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc. 2021;59:409-416. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | van Hagen P, Hulshof MC, van Lanschot JJ, Steyerberg EW, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Wijnhoven BP, Richel DJ, Nieuwenhuijzen GA, Hospers GA, Bonenkamp JJ, Cuesta MA, Blaisse RJ, Busch OR, ten Kate FJ, Creemers GJ, Punt CJ, Plukker JT, Verheul HM, Spillenaar Bilgen EJ, van Dekken H, van der Sangen MJ, Rozema T, Biermann K, Beukema JC, Piet AH, van Rij CM, Reinders JG, Tilanus HW, van der Gaast A; CROSS Group. Preoperative chemoradiotherapy for esophageal or junctional cancer. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2074-2084. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3288] [Cited by in RCA: 4272] [Article Influence: 305.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 13. | Rice TW, Blackstone EH, Rusch VW. 7th edition of the AJCC Cancer Staging Manual: esophagus and esophagogastric junction. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1721-1724. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 571] [Cited by in RCA: 644] [Article Influence: 40.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Luketich JD, Pennathur A, Awais O, Levy RM, Keeley S, Shende M, Christie NA, Weksler B, Landreneau RJ, Abbas G, Schuchert MJ, Nason KS. Outcomes after minimally invasive esophagectomy: review of over 1000 patients. Ann Surg. 2012;256:95-103. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 647] [Cited by in RCA: 645] [Article Influence: 46.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Shapiro J, van Lanschot JJB, Hulshof MCCM, van Hagen P, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Wijnhoven BPL, van Laarhoven HWM, Nieuwenhuijzen GAP, Hospers GAP, Bonenkamp JJ, Cuesta MA, Blaisse RJB, Busch ORC, Ten Kate FJW, Creemers GM, Punt CJA, Plukker JTM, Verheul HMW, Bilgen EJS, van Dekken H, van der Sangen MJC, Rozema T, Biermann K, Beukema JC, Piet AHM, van Rij CM, Reinders JG, Tilanus HW, Steyerberg EW, van der Gaast A; CROSS study group. Neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy plus surgery versus surgery alone for oesophageal or junctional cancer (CROSS): long-term results of a randomised controlled trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:1090-1098. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1292] [Cited by in RCA: 1932] [Article Influence: 175.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Ng T, Dipetrillo T, Purviance J, Safran H. Multimodality treatment of esophageal cancer: a review of the current status and future directions. Curr Oncol Rep. 2006;8:174-182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ajani JA, D'Amico TA, Bentrem DJ, Cooke D, Corvera C, Das P, Enzinger PC, Enzler T, Farjah F, Gerdes H, Gibson M, Grierson P, Hofstetter WL, Ilson DH, Jalal S, Keswani RN, Kim S, Kleinberg LR, Klempner S, Lacy J, Licciardi F, Ly QP, Matkowskyj KA, McNamara M, Miller A, Mukherjee S, Mulcahy MF, Outlaw D, Perry KA, Pimiento J, Poultsides GA, Reznik S, Roses RE, Strong VE, Su S, Wang HL, Wiesner G, Willett CG, Yakoub D, Yoon H, McMillian NR, Pluchino LA. Esophageal and Esophagogastric Junction Cancers, Version 2.2023, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2023;21:393-422. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 339] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 18. | Ozawa S, Ando N, Shinozawa Y, Ohmori T, Kase K, Sato T, Abe O. Two cases of resected esophageal mucoepidermoid carcinoma. Jpn J Surg. 1989;19:86-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Batoon SB, Banzuela M, Angeles HG, Zoneraich S, Maniego W, Co J. Primary mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the esophagus misclassified as adenocarcinoma on endoscopic biopsy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:2998-2999. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Turkyilmaz A, Eroglu A, Gursan N. Muco-epidermoid carcinoma of the oesophagus: a case report. Acta Chir Belg. 2009;109:416-418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Chen S, Chen Y, Yang J, Yang W, Weng H, Li H, Liu D. Primary mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the esophagus. J Thorac Oncol. 2011;6:1426-1431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kiyozaki H, Obitsu T, Ishioka D, Saito M, Chiba F, Takata O, Hiruta M, Yamada S, Rikiyama T. A rare case of primary mucoepidermoid carcinoma of the esophagus. Clin J Gastroenterol. 2015;8:26-28. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Jeun SE, Kim KB, Lee BE, Kim GH, Lee MW, Joo DC. A rare case of esophageal mucoepidermoid carcinoma successfully treated via endoscopic submucosal dissection. Clin Endosc. 2024;57:683-687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/