Published online Oct 26, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i30.109977

Revised: June 4, 2025

Accepted: August 8, 2025

Published online: October 26, 2025

Processing time: 137 Days and 18.2 Hours

This case report presents an innovative approach to managing a complex class II division 1 malocclusion with ectopic maxillary canines using a modified twin block (TB) appliance. The modification facilitated simultaneous skeletal correction and canine eruption, reducing treatment time and improving patient satisfaction.

A 14-year-old male presented with concerns about a retruded chin and spacing between teeth. Clinical and radiographic evaluation revealed a class II division 1 malocclusion on a moderate class II skeletal base, with palatally impacted maxillary canines. Treatment involved a modified Clark TB appliance designed with hooks to allow active traction of the canines, followed by comprehensive fixed orthodontics. Over 18 months, the patient achieved improved occlusion, corrected overjet and overbite, successful eruption of the impacted canines, and enhanced facial aesthetics. The final results showed significant dental and skeletal improvement without requiring surgical intervention.

A modified TB appliance can effectively manage class II malocclusion with impacted canines in growing patients. The modified approach combining func

Core Tip: This case report highlights a non-surgical, dual-phase approach for treating class II division 1 malocclusion with impacted maxillary canines in an adolescent patient. A modified twin block appliance enabled simultaneous mandibular advancement and active canine traction, streamlining treatment and improving outcomes. The innovative appliance design reduced the need for additional anchorage, shortened treatment time, and enhanced facial and dental aesthetics, demonstrating a practical alternative to more invasive or prolonged treatment strategies.

- Citation: Alomair D, Halawani MR, Alsubaye S, Almajed AA. Treatment of class II malocclusion and ectopic maxillary canines: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(30): 109977

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i30/109977.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i30.109977

Several treatment modalities have proven effective in managing class II malocclusion. The optimal treatment approach depends on multiple factors, including the severity of the malocclusion, the patient’s age, their perception of the problem, the range of available treatment options, and financial considerations[1]. Customizing the treatment plan based on these factors is essential to achieving successful, patient-centered outcomes.

Functional appliances are a well-established option for managing class II malocclusions in growing individuals, particularly those with mild to moderate class II skeletal discrepancies caused by mandibular retrognathia and characterized by average or reduced vertical facial proportions[2]. Evidence suggests that the effects of functional appliances are predominantly dentoalveolar, with limited skeletal changes such as modest increases in mandibular length. Nonetheless, notable enhancements in soft tissue profile are frequently observed, although individual responses can vary significantly[2,3].

Current literature supports the use of functional appliances during or shortly after the onset of the pubertal growth spurt, when skeletal responsiveness is at its peak. Assessment of skeletal maturity using the cervical vertebrae maturation (CVM) index has shown that the most favorable dentoskeletal outcomes are achieved when treatment is initiated at stages 3 or 4, which correspond to the peak or immediate post-peak growth period[4,5].

The therapeutic effects of functional appliances in growing patients include proclination of the lower incisors, retro

There are various functional appliances available, each with distinct design features. Among them, the twin block (TB) appliance is one of the most widely used. It has been shown to effectively reduce overjet and overbite while significantly enhancing the soft tissue profile, typically within six to nine months of consistent use. Moreover, the TB’s simplified, two-piece design tends to be more comfortable and better accepted by patients compared to traditional monoblock appliances[10]. In this case report, we present a medically fit 14-year-old Caucasian male who presented with concerns about spacing between his teeth and a retruded lower jaw. Clinical examination revealed a Class II Division 1 malocclusion on a moderate class II skeletal base, primarily due to a retrognathic mandible, and further complicated by ectopically posi

A 14-year-old Caucasian male presented with complaints of excessive spacing between his teeth and a retruded lower jaw.

The patient reported concerns related to the appearance of his smile, including noticeable spacing and a retrusive chin. He expressed dissatisfaction with unerupted teeth and requested orthodontic correction.

The patient was medically fit and well, with no known systemic illnesses or previous orthodontic treatment.

There was no significant personal or family history relevant to orthodontic or craniofacial anomalies.

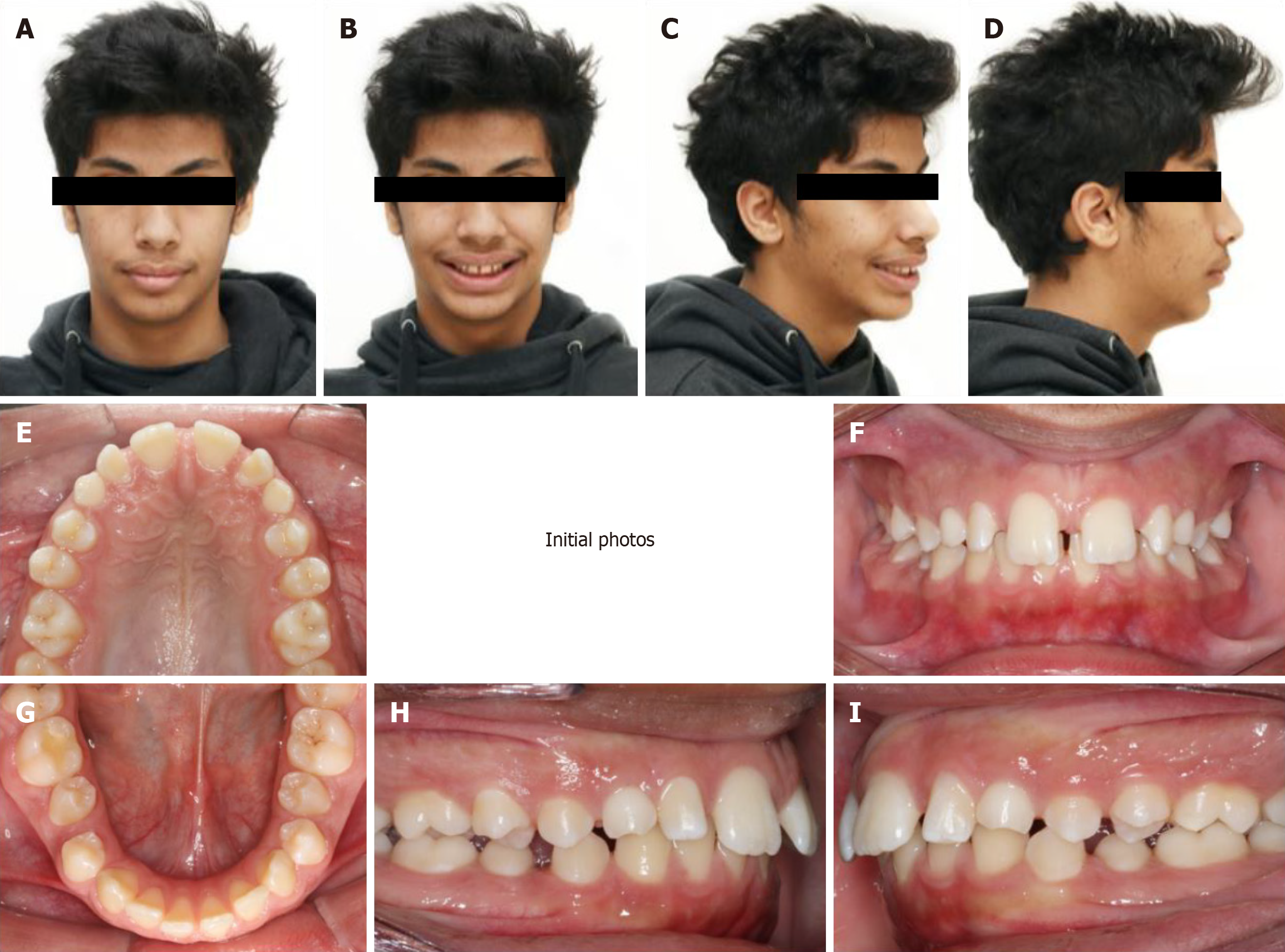

Extra-oral examination revealed a moderate class II skeletal base with an average Frankfort mandibular plane angle and lower anterior face height. The nasal tip deviated to the left. The soft tissue profile was marked by a potentially competent lip (due to the lower lip being trapped behind the upper incisors), average nasolabial and deep labio-mental angles, and a retruded chin relative to the Zero-meridian line (Figure 1). Initial evaluation of CVM placed the patient at the transition between CVM stages 4 and 5, indicating residual growth potential suitable for functional appliance therapy.

Intra-oral examination showed a full permanent dentition except for the unerupted upper canines and third molars. The upper primary canines were retained. Spacing was noted: 5 mm in the mandibular arch and 10 mm in the maxillary arch. The patient had a class II division 1 incisor relationship, with an 8 mm overjet and an increased, traumatic overbite. A scissor bite was present on the second premolars. Buccal segments were half-unit class II on the right and quarter-unit class II on the left (Figure 1).

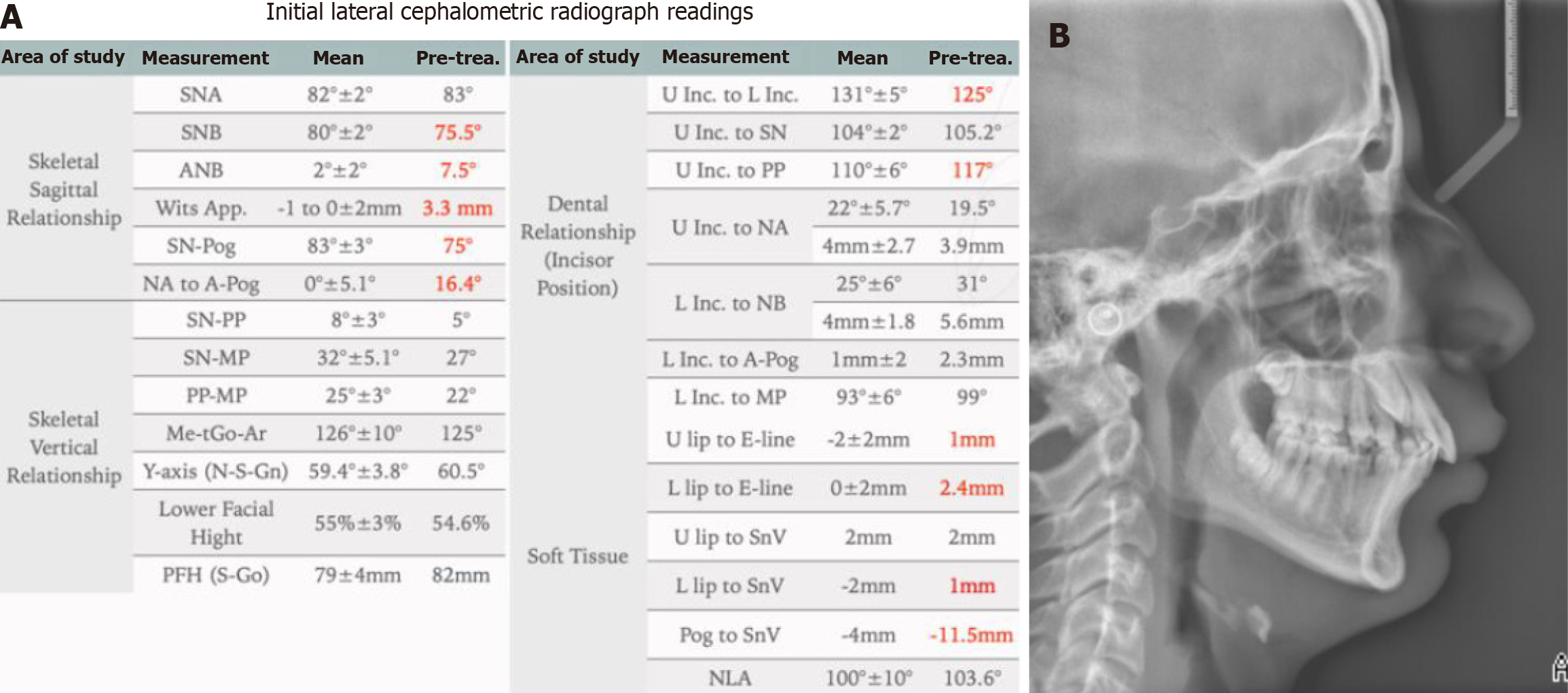

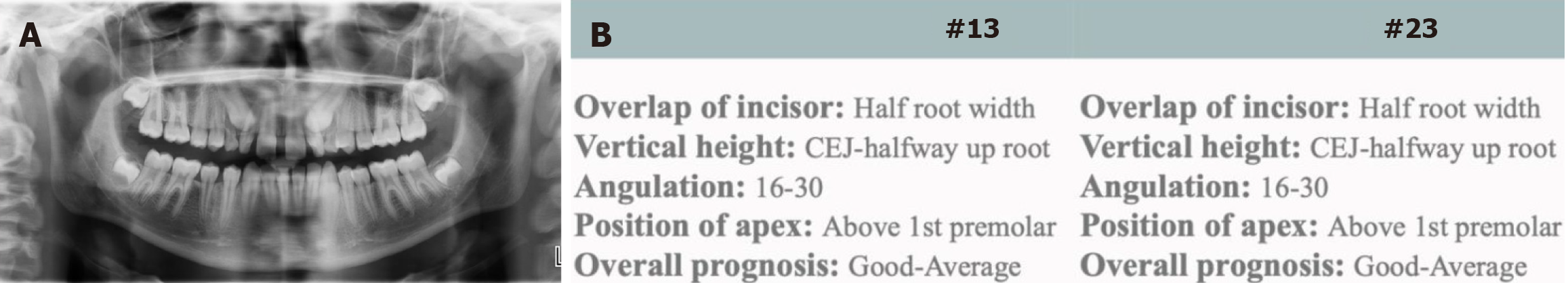

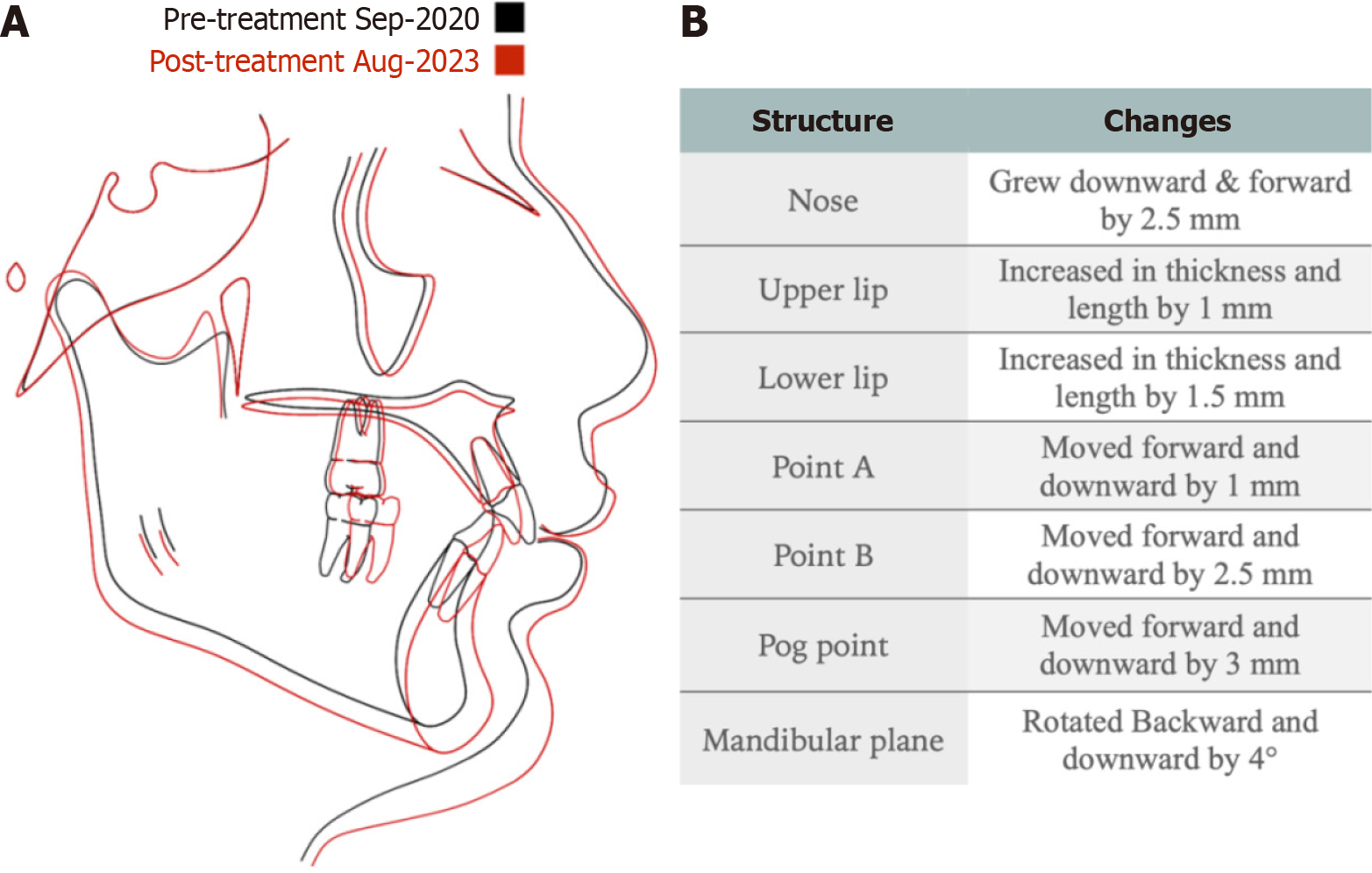

Cephalometric analysis confirmed the extra-oral skeletal findings (Figure 2). A panoramic radiograph revealed palatally impacted upper right canine (#13) and upper left canine (#23), with an average to good prognosis (Figure 3).

The patient was referred to a restorative dentist to restore carious lesions and evaluate peg-shaped maxillary lateral incisors. A periodontist was consulted for open surgical exposure of the impacted maxillary canines.

Class II division 1 malocclusion on a moderate class II skeletal base with retrognathic mandible and palatally impacted upper canines (#13 and #23).

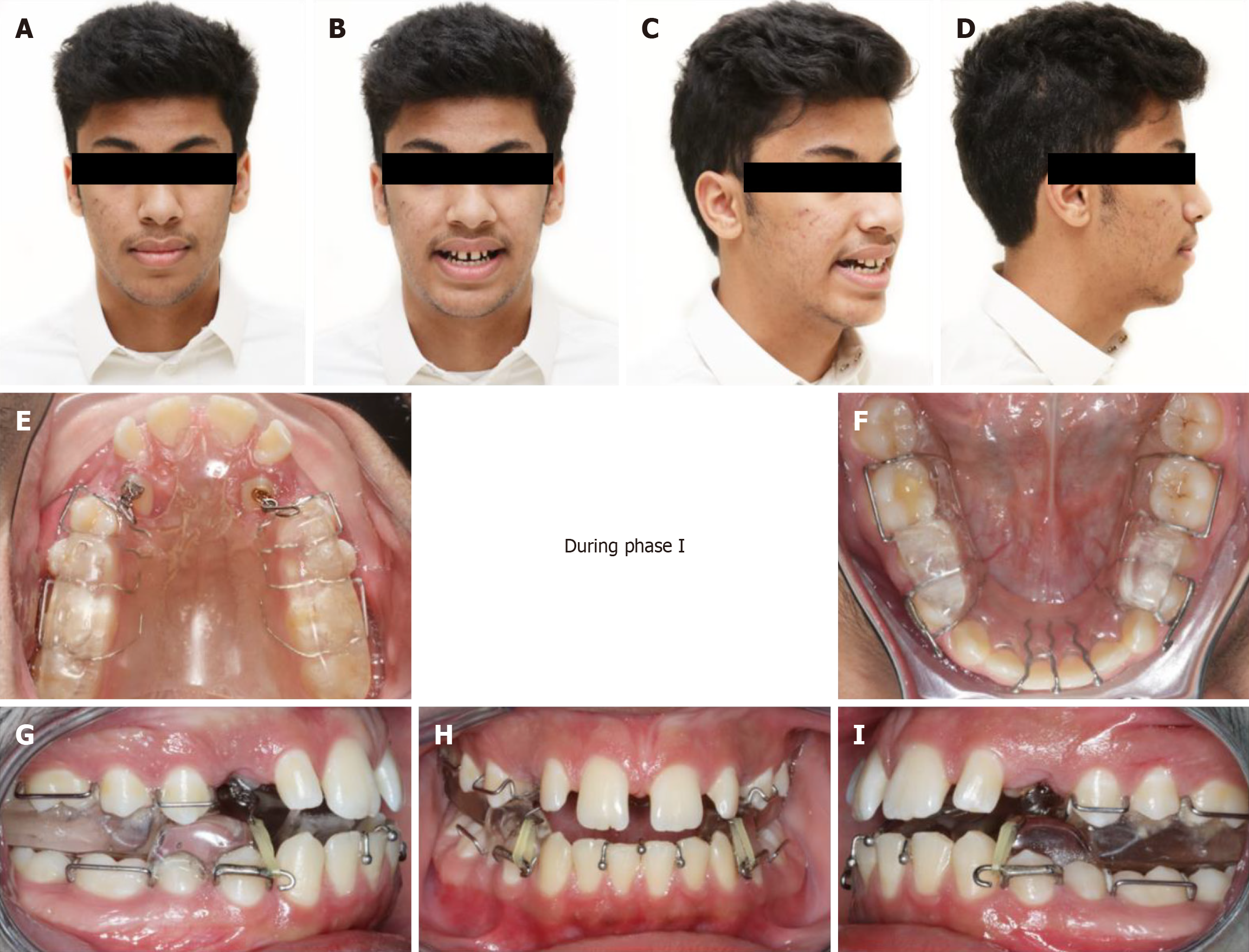

A two-phase non-extraction, non-surgical treatment plan was implemented: Phase I: Growth modification with a modified Clark TB appliance over 12 months. The appliance was designed with extended hooks for canine traction. After functional assessment and compliance confirmation, beta titanium hooks were bonded to the exposed canines, and inter-arch elastics (4.5 oz) were applied (Figures 4 and 5). Monthly follow-ups were conducted. After nine months, the functional results were reviewed (Figures 6 and 7), and the appliance was continued as a night-time retainer for three months. Phase II: Fixed orthodontic treatment with 0.022” MBT prescription brackets to level and align both arches. The maxillary lateral incisors were built up by a restorative dentist to address Bolton discrepancy. Total treatment duration was 18 months. Retention was maintained with both fixed and removable retainers (Figure 8).

Detailed cephalometric analysis confirmed favorable control of incisor inclinations: Lower incisor to mandibular plane angle remained within normal limits (pre-treatment: 99°, final: 96°), and upper incisor inclination improved from 117° to 112°. Strategic space utilization and careful biomechanics ensured periodontal integrity and aesthetic stability. The patient showed excellent compliance. Impacted canines successfully erupted, and skeletal and dental relationships sig

Functional appliances remain a cornerstone in the management of class II malocclusions in growing patients[6]. The modified TB appliance used in this case not only facilitated mandibular advancement but also provided active traction for impacted maxillary canines, allowing for a comprehensive, non-surgical correction[5,11]. Although the use of TB app

While CVM stages 3 and 4 are optimal for functional appliance therapy, studies have shown continued skeletal response into early stage 5, especially in compliant patients[4,12]. In this case, the patient’s cephalometric radiographs confirmed ongoing growth activity, supporting the clinical decision to initiate TB therapy during this phase. A critical element in treatment planning was the Index of Orthodontic Treatment Need dental health component score of 5i, indicating a “very great need” for orthodontic intervention[10]. Given the skeletal and dental complexity of the case, a multidisciplinary approach was necessary, involving restorative and periodontal input for optimal outcomes.

In addition to fixed functional appliances and clear aligner therapy, skeletal anchorage methods such as mini-implants or mini-plates were considered as potential alternatives for overjet reduction through distalization. However, these would not have addressed the patient’s chief concern of a retruded chin. Orthognathic surgery was also discussed as a future option if residual discrepancies persisted post-growth, but was deferred in favour of a less invasive, growth-guided strategy aligned with the patient’s and guardian’s preferences. Alternative treatment options were considered and discussed with the patient and his family. Among these were fixed functional appliances such as the Herbst appliance, and newer methods like Invisalign with mandibular advancement (MA). In a randomized clinical trial, O'Brien et al[13] demonstrated that both TB and Herbst appliances were effective in correcting class II malocclusions primarily through dentoalveolar changes, with minor skeletal improvement. However, the TB group showed a higher treatment discontinuation rate, while the Herbst group had more emergency visits and incurred greater overall treatment costs.

Pacha et al[14] conducted a systematic review comparing complications between fixed and removable functional appliances. Their analysis revealed significantly higher complication rates (69%) in fixed/hybrid appliances vs 34% in removable appliances. Furthermore, removable appliances were associated with fewer emergency visits, though they had higher rates of treatment discontinuation (35%) compared to fixed appliances (1%). These findings underscore the importance of selecting a treatment modality based not only on clinical efficacy but also on patient quality of life and compliance.

Invisalign with MA was also considered. Introduced in 2017 by Align Technology, this system combines mandibular advancement with clear aligner therapy, offering enhanced aesthetics, digital treatment planning, and better patient acceptability[15]. Nevertheless, the literature suggests that rotational and inclination movements, especially of palatally impacted canines, are challenging to achieve with clear aligners[16]. Studies comparing TB and Invisalign with MA show improvements in overjet, overbite, and soft tissue profile in both groups, but TB-treated patients exhibited more pro

Orthodontic-orthognathic surgery was another theoretical option, particularly given the skeletal class II base. While this approach offers profound facial aesthetic and skeletal corrections, it carries risks including invasiveness, cost, and the need to delay treatment until growth cessation[20]. Considering the presence of impacted canines and the patient’s ongoing growth, early orthodontic intervention with functional appliance therapy was deemed the most appropriate path.

Despite the slightly delayed timing relative to optimal pubertal growth stages, the patient still benefited from growth modification. Cephalometric superimposition confirmed improvements in sagittal jaw relationship and upper/Lower incisor inclinations. Nonetheless, the patient and family were informed of the potential for future orthognathic surgery if residual facial discrepancies remained post-growth. Although incisor proclination is a known side effect of functional appliance use, in this case, controlled biomechanics and space management allowed for a slight retroclination of both upper and lower incisors. This contributed to improved soft tissue profile and periodontal health.

Long-term stability of results achieved through TB therapy is supported by studies from Oliver et al[21] and Moro et al[22], both of which demonstrate favorable outcomes in Class II patients treated with TB appliances . Critical determinants of post-treatment stability include interincisal angle normalization, favorable soft tissue adaptation, good buccal interdigitation, and diligent retainer use[23].

This case demonstrates that a modified TB appliance can serve dual functions in growing patients with Class II Division 1 malocclusion and ectopic maxillary canines, facilitating both mandibular advancement and active canine traction. This non-surgical, non-extraction approach provided effective skeletal and dental correction, improved facial aesthetics, and shortened overall treatment duration. Incorporating such modifications into functional appliance therapy may offer a valuable alternative to more invasive interventions, especially when timed appropriately during the growth phase.

| 1. | Lone IM, Zohud O, Midlej K, Proff P, Watted N, Iraqi FA. Skeletal Class II Malocclusion: From Clinical Treatment Strategies to the Roadmap in Identifying the Genetic Bases of Development in Humans with the Support of the Collaborative Cross Mouse Population. J Clin Med. 2023;12:5148. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Batista KB, Thiruvenkatachari B, Harrison JE, O'Brien KD. Orthodontic treatment for prominent upper front teeth (Class II malocclusion) in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;3:CD003452. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Baysal A, Uysal T. Dentoskeletal effects of Twin Block and Herbst appliances in patients with Class II division 1 mandibular retrognathy. Eur J Orthod. 2014;36:164-172. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Cozza P, Baccetti T, Franchi L, De Toffol L, McNamara JA Jr. Mandibular changes produced by functional appliances in Class II malocclusion: a systematic review. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2006;129:599.e1-12; discussion e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 213] [Cited by in RCA: 265] [Article Influence: 13.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Baccetti T, Franchi L, Toth LR, McNamara JA Jr. Treatment timing for Twin-block therapy. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2000;118:159-170. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in RCA: 198] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Vaid NR, Doshi VM, Vandekar MJ. Class II treatment with functional appliances: A meta-analysis of short-term treatment effects. Semin Orthod. 2014;20:324-338. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Ehsani S, Nebbe B, Normando D, Lagravere MO, Flores-Mir C. Short-term treatment effects produced by the Twin-block appliance: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Orthod. 2015;37:170-176. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Zymperdikas VF, Koretsi V, Papageorgiou SN, Papadopoulos MA. Treatment effects of fixed functional appliances in patients with Class II malocclusion: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Orthod. 2016;38:113-126. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 160] [Cited by in RCA: 139] [Article Influence: 13.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Santamaría-Villegas A, Manrique-Hernandez R, Alvarez-Varela E, Restrepo-Serna C. Effect of removable functional appliances on mandibular length in patients with class II with retrognathism: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Oral Health. 2017;17:52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Shaw WC, Richmond S, O'Brien KD, Brook P, Stephens CD. Quality control in orthodontics: indices of treatment need and treatment standards. Br Dent J. 1991;170:107-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 122] [Cited by in RCA: 124] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Mills JR. The effect of functional appliances on the skeletal pattern. Br J Orthod. 1991;18:267-275. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 54] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | McNamara JA Jr, Franchi L. The cervical vertebral maturation method: A user's guide. Angle Orthod. 2018;88:133-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 148] [Article Influence: 18.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | O'Brien K, Wright J, Conboy F, Sanjie Y, Mandall N, Chadwick S, Connolly I, Cook P, Birnie D, Hammond M, Harradine N, Lewis D, McDade C, Mitchell L, Murray A, O'Neill J, Read M, Robinson S, Roberts-Harry D, Sandler J, Shaw I. Effectiveness of treatment for Class II malocclusion with the Herbst or twin-block appliances: a randomized, controlled trial. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2003;124:128-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 162] [Cited by in RCA: 155] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Pacha MM, Fleming PS, Shagmani M, Johal A. The skeletal and dental effects of Hanks Herbst versus twin block appliances for class II correction in growing patients: a randomized clinical trial. Eur J Orthod. 2024;46:cjad065. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Hosseini HR. A comparison of skeletal, dental changes in Class II patients treated with Invisalign® with Mandibular Advancement and Herbst appliance. University of British Columbia, 2022. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 16. | Zybutz T, Drummond R, Lekic M, Brownlee M. Investigation and comparison of patient experiences with removable functional appliances. Angle Orthod. 2021;91:490-495. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Meade MJ, Weir T. Clinical efficacy of the Invisalign mandibular advancement appliance: A retrospective investigation. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2024;165:503-512. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Lombardo EC, Lione R, Franchi L, Gaffuri F, Maspero C, Cozza P, Pavoni C. Dentoskeletal effects of clear aligner vs twin block-a short-term study of functional appliances. J Orofac Orthop. 2024;85:317-326. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Wu Y, Yu Q, Xia Y, Wang B, Chen S, Gu K, Zhang B, Zhu M. Does mandibular advancement with clear aligners have the same skeletal and dentoalveolar effects as traditional functional appliances? BMC Oral Health. 2023;23:65. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Kim YK. Complications associated with orthognathic surgery. J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2017;43:3-15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 90] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Oliver GR, Pandis N, Fleming PS. A prospective evaluation of factors affecting occlusal stability of Class II correction with Twin-block followed by fixed appliances. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2020;157:35-41. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Moro A, Mattos CFP, Borges SW, Flores-Mir C, Topolski F. Stability of Class II corrections with removable and fixed functional appliances: A literature review. J World Fed Orthod. 2020;9:56-67. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Millett D. The rationale for orthodontic retention: piecing together the jigsaw. Br Dent J. 2021;230:739-749. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/