Published online Oct 26, 2025. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v13.i30.108566

Revised: July 5, 2025

Accepted: August 15, 2025

Published online: October 26, 2025

Processing time: 177 Days and 15.9 Hours

Basidiobolomycosis, a fungal infection affecting immunocompetent indivi

Herein, we present a case of GIB in a 32-year-old Saudi male, and smoker who presented with a 2-month history of mild-to-moderate pain in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen. On clinical suspicion of colon cancer due to the presence of an ileocecal mass on imaging studies, he underwent a colonoscopy and endoscopic biopsy followed by histopathological examination. The latter revealed colonic mucosal fragments showing ulceration, granulation tissue, and marked eosinophilic as well as mixed inflammatory cell infiltration along with scattered giant cells. A few scattered, thin-walled, broad fungal hyphae were evident on special stains. Based on the histopathological findings, the patient was diagnosed with GIB. He was started on voriconazole, but switched to posaconazole after 5 weeks because the patient developed hepatotoxicity. After about 4 months of treatment with posaconazole, he was asymptomatic, and abdominal CT revealed complete resolution of the mass lesion.

This case highlights the rare presentation of GIB in an immunocompetent adult initially misdiagnosed as colon cancer, emphasizing the importance of histopathological evaluation in diagnosing fungal infections. It also underscores successful treatment with posaconazole following voriconazole-induced hepatotoxicity, demon

Core Tip: Gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis (GIB) is a rare but potentially fatal fungal infection affecting immunocompetent individuals, often mimicking malignancy. This case highlights a 32-year-old Saudi male presenting with right lower quadrant abdominal pain and an ileocecal mass, initially suspected as colon cancer. Colonoscopy and histopathology confirmed GIB, revealing fungal hyphae, eosinophilic infiltration, and granulomatous inflammation. Voriconazole therapy induced hepatotoxicity, necessitating a switch to posaconazole. The patient achieved full clinical and radiological resolution after four months. Early recognition and targeted antifungal therapy are essential for favorable outcomes. This case underscores the importance of considering GIB in the differential diagnoses of abdominal masses in endemic regions.

- Citation: Alsulaimi MS, Memon MY, Alyabary IM, Almotairi E, Sulaiman T, Shamsan AN, Mubarak M. Ileocecal basidiobolomycosis mimicking malignancy successfully treated without surgery: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2025; 13(30): 108566

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v13/i30/108566.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v13.i30.108566

Basidiobolomycosis is a rare fungal infection caused by Basidiobolus ranarum (B. ranarum), a saprophytic fungus that belongs to the class Entomophthoromycetes[1]. Unlike many other fungal infections, this disease can affect immunocompetent individuals. Gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis (GIB) is predominantly found in tropical and subtropical regions[2-6]. Although rare, its incidence is rising, particularly in areas like southern Tohama in Saudi Arabia, which has reported the highest number of cases[7].

It primarily involves the skin and subcutaneous tissues, but it can also spread to extracutaneous organs, including the kidneys, lungs, gastrointestinal (GI) tract, and other organ systems[8,9]. GIB, in particular, can be life-threatening and has been associated with a notable mortality risk approaching 15% in some case series[10]. However, timely diagnosis and appropriate management, combining antifungal therapy and surgical resection of affected tissues, have been shown to improve patient outcomes[3-7].

GIB primarily affects the intestinal tract, with the colon being the most commonly involved site. Patients typically present with symptoms such as fever, abdominal pain, weight loss, constipation or diarrhea, and intra-abdominal mass lesions. Laboratory findings often include peripheral blood eosinophilia and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate. These nonspecific clinical and laboratory features can mimic a wide range of conditions, including lymphoma, amebiasis, colon cancer, sarcoidosis, chronic granulomatous diseases like tuberculosis, and inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Due to its varied and nonspecific presentation, GIB is frequently misdiagnosed or diagnosed late, complicating patient management[11-13].

Definitive diagnosis relies on a combination of culture, imaging, biopsy, histopathological examination, and advanced molecular biology techniques. Treatment typically involves long-term antifungal therapy with variable duration, which varies from a few months to 2 years, and surgical resection when necessary[14].

This case report highlights an unusual presentation of GIB initially mimicking a malignant ileocecal mass. The diagnosis was established by colonoscopy and histopathology, highlighting the relevance of considering fungal etiologies in atypical abdominal masses.

A 32-year-old male, smoker, and a resident of Saudi Arabia, presented in the emergency room (ER) multiple times with complaints of mild to moderate pain in the right lower quadrant of the abdomen, particularly the ileocecal region, for approximately two months.

The patient reported a two-month history of intermittent abdominal pain in the right iliac fossa. The pain was described as mild to moderate, dull and aching, relieved with pain killers like acetaminophen with no associated vomiting, diarrhea, or overt gastrointestinal bleeding. He denied any changes in bowel habits, fever, or urinary complaints. This resulted in frequent ER visits. On the latest visit, GI was also consulted, along with a consultation with General Surgery.

He was not known to have any chronic illness like diabetes, hypertension, or any autoimmune disease. The patient had no family history of colon cancer.

The patient was a resident of Saudi Arabia, a smoker for a few years, about a pack per day. He denied any history of alcohol and was not addicted to anything. There were no reported instances of intentional or unintentional weight loss. There was no recent travel history or parasitic exposure, or any major dietary changes. There was no history of intake of immunosuppressive drugs.

The patient was vitally stable and conscious. Physical examination revealed the abdomen to be soft and lax with mild tenderness at the right iliac fossa. The other systemic examination was normal.

The complete blood count results showed a slightly elevated white blood cell count (14 × 103/mm3) with a significant eosinophilia (14.43%, 1.94 × 109/L) and a normal neutrophil count (55%, 7.43 × 109/L), along with a normal hemoglobin level (16.6 g/dL). The serum albumin level was 48 g/L, and the blood urea nitrogen was 3.6 mg/dL. The serum creatinine was 77 μmol/L.

Based on the symptoms, the patient was initially suspected of having appendicitis. The initial imaging study performed was an abdominal ultrasound, which demonstrated bowel wall thickening at the ileocecal region with mild adjacent fat stranding. No obvious abscess or free fluid was seen. The appendix was not clearly visualized. These findings raised suspicion for inflammatory or infiltrative pathology, prompting further evaluation.

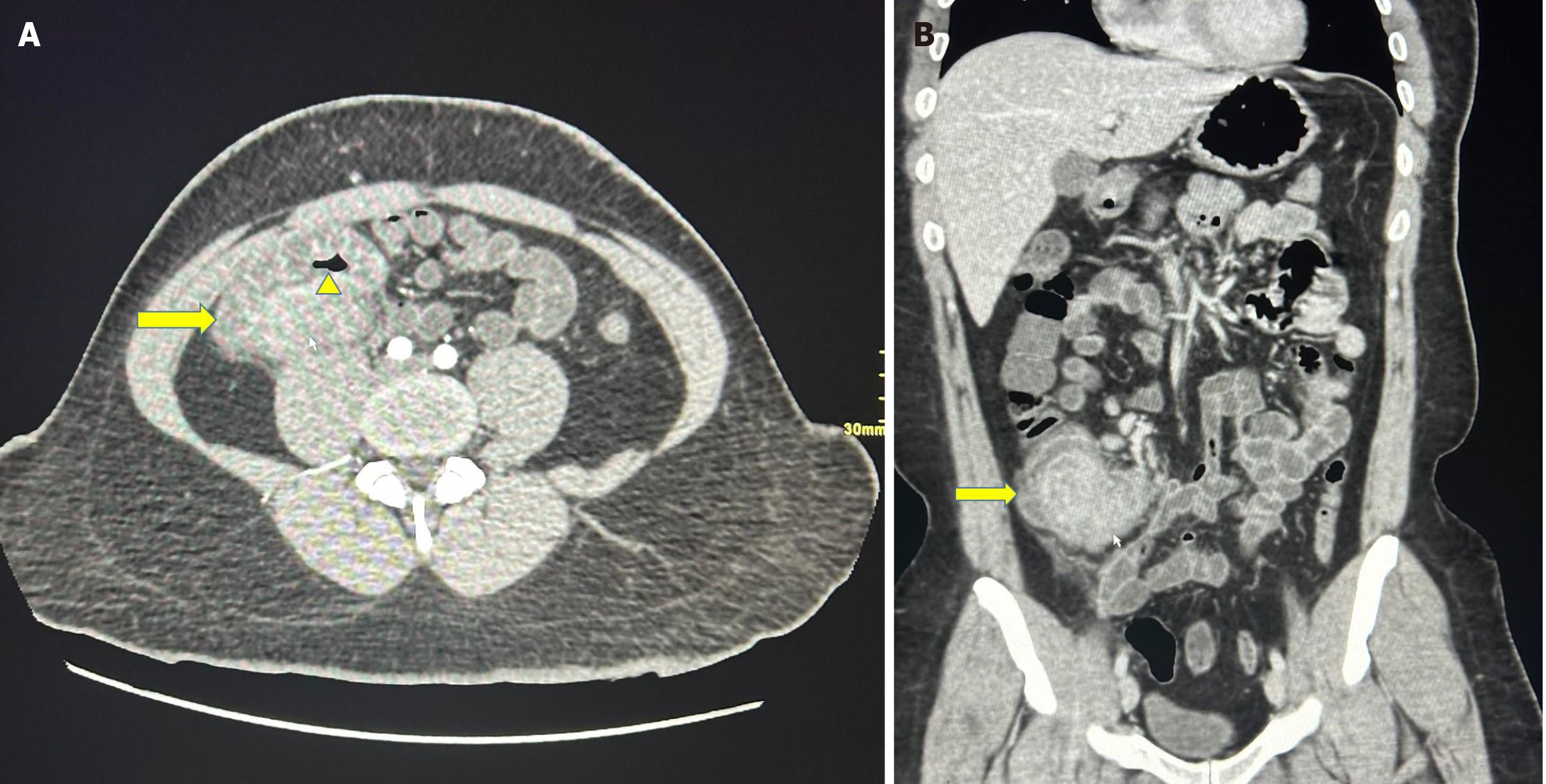

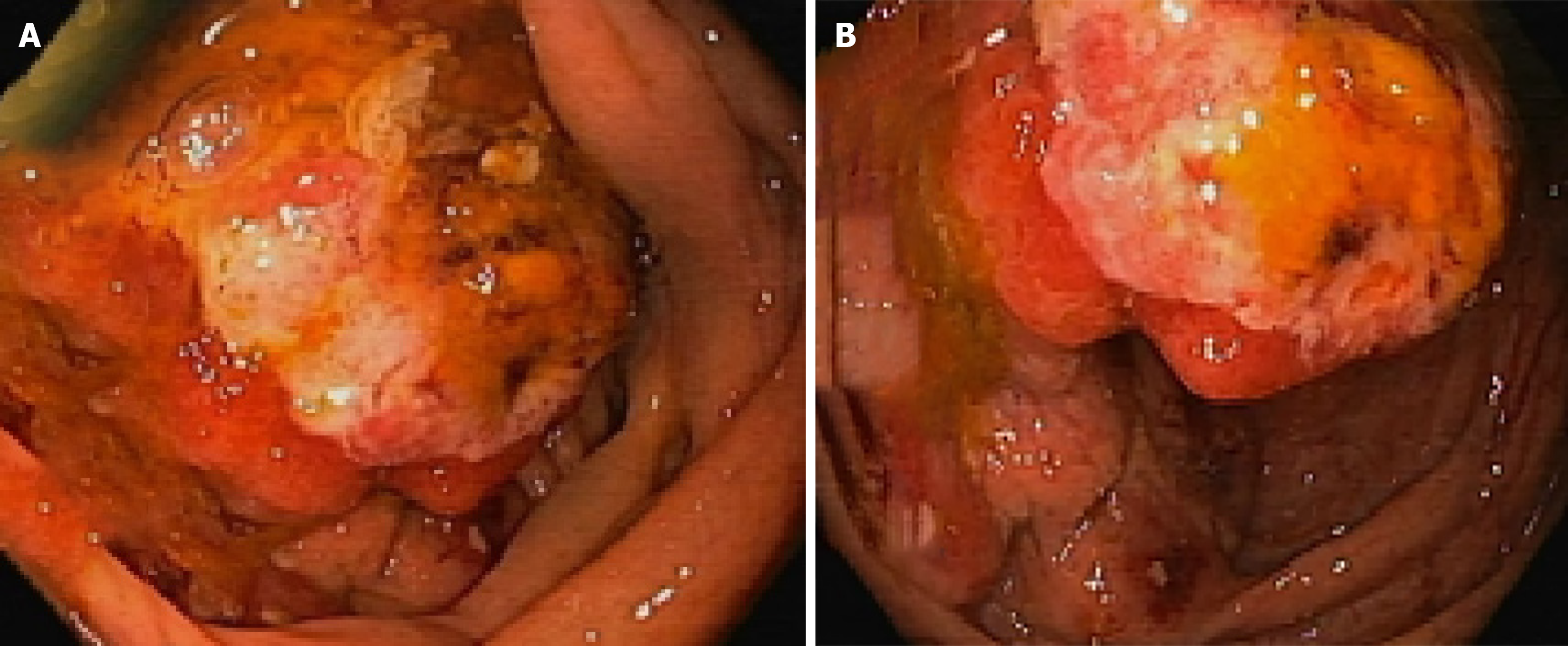

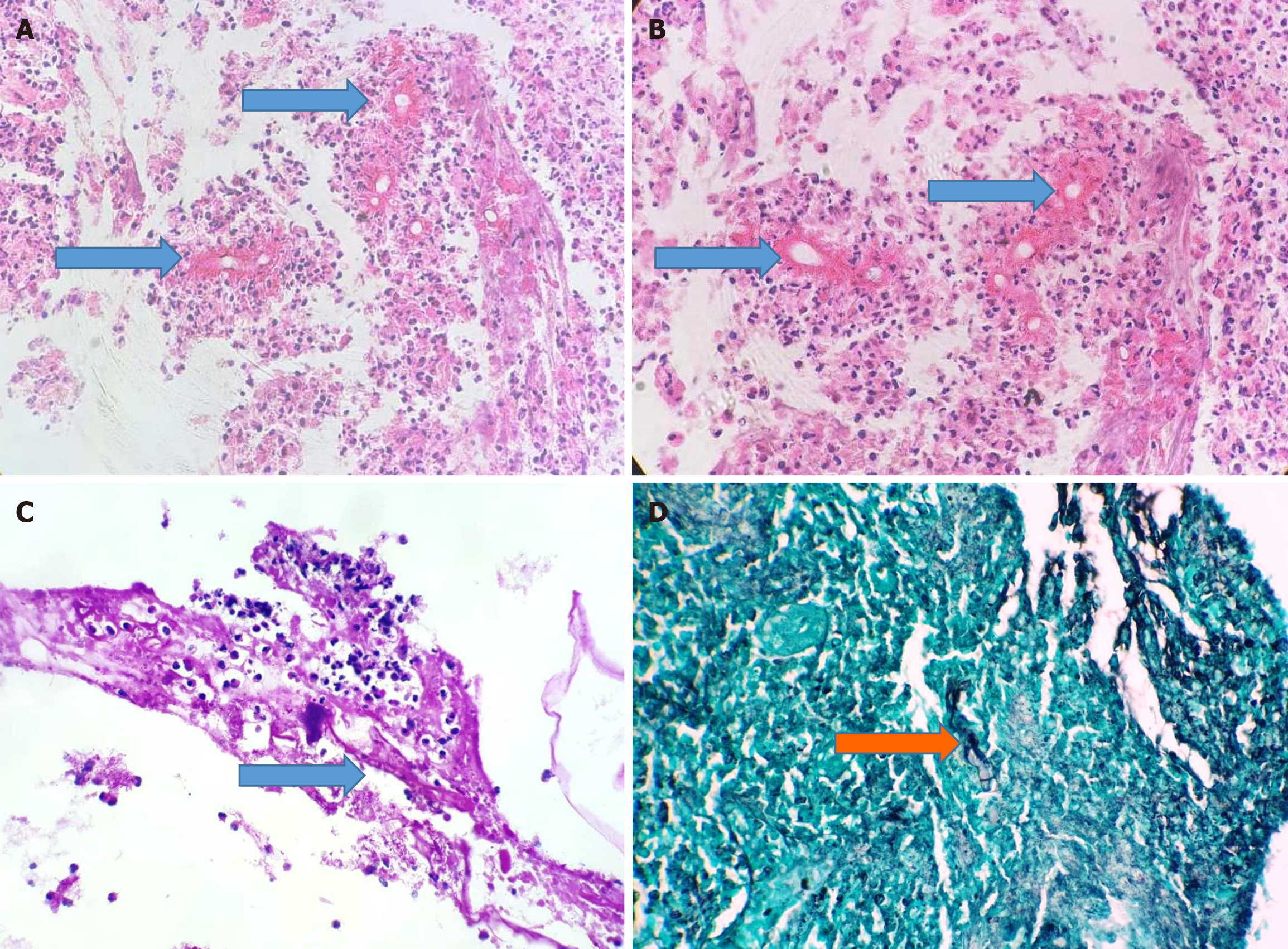

Further investigations included computed tomography (CT) of the lower abdomen, which showed the presence of an ileocecal mass involving the ileocecal valve (ICV) without obstruction associated with ileocolic lymphadenopathy (Figure 1). The imaging suspicion of malignancy led to a colonoscopy, which was performed up to the cecum, and the results obtained further endorsed the findings of previous imaging studies. Specifically, the appendicular orifice was identified, with the cecum showing a granular friable fungating mass lesion on the medial side around the ICV extending to the proximal colon for about 2 cm. The fungating mass lesion protruded into the lumen, covering approximately two-thirds of its circumference (Figure 2). Multiple biopsies were taken from the mass for histopathological examination. A small sub-pedunculated hyperplastic polyp, measuring approximately 6 mm, was observed in the sigmoid colon and removed with a cold snare. The other parts of the colon, including the ascending, transverse, and descending colon, exhibited normal morphology. The histopathological examination showed multiple fragments of colonic mucosa with ulcerated regions and necro-inflammatory debris. The inflammation consisted of mixed inflammatory cells, including lymphocytes, histiocytes, neutrophils, scattered giant cells, and abundant eosinophils, along with granulation tissue formation. A few scattered fungal hyphae were also identified surrounded by dense, pink, hyaline material, giving rise to the Splendore-Hoeppli phenomenon (Figure 3A and B). On special stains of periodic acid-schiff (PAS) and Grocott's methenamine silver (GMS), the fungal hyphae were highlighted with occasional septation, suggestive of invasive fungal infection (Figure 3C and D). There was no evidence of definitive granuloma or malignancy.

The patient was then referred to the Infectious Disease (ID) department, where he was put on voriconazole, 200 mg, every 12 hours. After about 5 weeks, he developed deranged liver function tests (LFTs) with the highest reading as alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 494 U/L, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 321 U/L, total bilirubin 49.9 μmol/L and alkaline phosphatase 185 U/L. He was then switched to posaconazole, 100 mg daily, which was continued for 4 months.

Combining the appearance of the ileocecal mass lesion and the characteristic histopathological features, the features were suggestive of GIB.

The patient was then referred to the ID department, where he was put on voriconazole, 200 mg, every 12 hours. After about 5 weeks, he developed deranged LFTs with the highest reading as ALT 494 U/L, AST 321 U/L, total bilirubin 49.9 μmol/L and alkaline phosphatase 185 U/L. He was then switched to posaconazole, 100 mg daily, which was continued for 4 months.

The patient improved clinically with no more abdominal pain. He underwent CT abdomen/pelvis with contrast post-treatment, which showed almost complete resolution of the previously seen mass lesion at the ileocecal junction. The lymphadenopathy seen along the ileocecal region was stable, with the largest measuring approximately 1.8 cm with no increase in size. The rest of the bowel loops appeared unremarkable. No signs of bowel obstruction were noted. The patient was advised to undergo a repeat colonoscopy, but he refused. The total follow-up period from the initial diagnosis was about 10 months.

Although this case shares common features with most GIBs, such as abdominal pain, neutrophilia and significant eosinophilia, it also presents unique characteristics. Notably, the initial antifungal therapy with voriconazole caused side effects, necessitating a switch to posaconazole, which was better tolerated and proved effective. The case report highlights the importance of monitoring for side effects and adjusting treatment accordingly. It demonstrates successful non-surgical management of ileocecal basidiobolomycosis, which is a rare site. The case also highlights the importance of early diag

B. ranarum, the causative agent of GIB, is a saprophytic filamentous fungus from Basidiobolomycetes, which was previously designated as zygomycetes. It thrives in warm and humid environments, making it more prevalent in tropical and subtropical regions. However, paradoxically, many cases have also been reported from arid and semi-arid regions, such as desert areas in the southwestern United States (e.g., Arizona) and Middle Eastern countries. In these climates, B. ranarum flourishes in soil and decaying vegetation. Poor sanitation and exposure to contaminated soil may contribute to the higher incidence in these regions. Infection occurs via ingestion or inoculation of B. ranarum spores from soil or decaying matter. The fungus invades the gastrointestinal wall, causing granulomatous inflammation and tissue necrosis. The predisposing factors include environmental, geographic, and host factors, including smoking, the presence of geckos, reptiles, or frogs in living places, walking barefoot in these places, and exposure to insect bites. The skin and soft tissues are the most common infection sites; however, the extracutaneous sites are also affected. The involvement of the gastrointestinal tract has been considered an extremely rare event; however, since its initial documentation in a 6-year-old Nigerian boy in 1964[15]. A 15-fold increase in GIB cases has been witnessed over the past few decades worldwide[5,16-20]. As of recent reviews, fewer than 150 cases of GIB have been reported worldwide. The majority of these cases have been documented in the last two decades, with increasing recognition of the disease[5,21]. Very few cases of ileocecal involvement have been reported. However, the exact number of ileo-cecal basidiobolomycosis cases is not known[5,22]. A higher incidence of infection has been seen in males than in females, with a ratio of 11:1 across various age groups. However, the average age reported is 37 years[5].

GIB poses a diagnostic challenge due to its nonspecific symptoms and radiologic features that often mimic malignancy or IBD. In this case, the presence of a mass-like lesion in the ileocecal region, along with abdominal pain and minimal systemic signs, raised suspicion for malignancy. However, such presentations can also overlap with certain gastrointestinal parasitic infections—particularly amoebiasis, schistosomiasis, and strongyloidiasis—which are known to cause mass-like lesions, mucosal thickening, and eosinophilic infiltrates[23,24].

Differentiating GIB from these infections relies heavily on histopathology, as fungal hyphae surrounded by eosinophilic material (Splendore-Hoeppli phenomenon) are pathognomonic for GIB[4]. Therefore, in endemic regions, GIB should be considered in the differential diagnosis of ileocecal masses, particularly when parasitic infections and malignancy are ruled out or unsupported by biopsy findings[5]. The case presented here is a fungal infection of the colon, as supported by the clinical context and histopathological findings, and the most likely diagnosis is ileocecal basidiobolomycosis. The typical complaints of pain, no indication of weight loss, eosinophilic infiltration, and abdominal mass are consistent with the documented literature. The histopathological examination indicating the presence of fungal hyphae and eosinophilic infiltration, along with the Splendore-Höeppli phenomenon has been observed in the past and is considered highly suggestive of B. ranarum. Unlike other fungi (e.g., Aspergillus or Mucor), Basidiobolus hyphae are wider and rarely branch. The Splendore-Hoeppli phenomenon is highly characteristic of basidiobolomycosis. It is important to mention here that due to overlapping clinical features, there are diagnostic difficulties. The lesion is often misdiagnosed, resulting in an increase in morbidity and mortality. A similar case was recently reported by Mohammadi and colleagues, where a case of GIB was initially misdiagnosed as colon cancer[13]. However, after successful follow-ups and the absence of any relapse, the patient was given treatment with liposomal amphotericin B, which resulted in a complete cure of the disease[13]. In the present case, the patient developed side effects voriconazole, but improved on another antifungal drug.

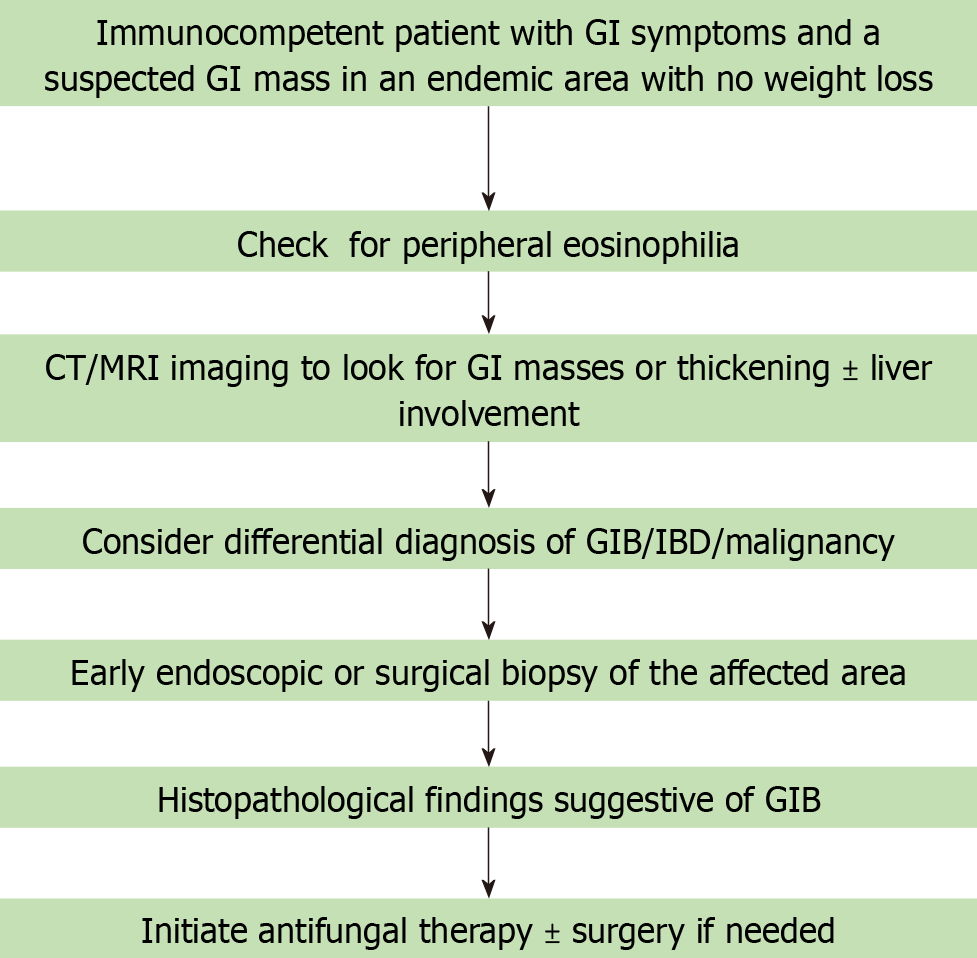

Early identification and treatment are critical to achieving favorable outcomes for the patients. Management usually involves multiple modalities, employing different approaches from antifungal therapy to surgical intervention. The patient discussed herein was referred to the ID department and was successfully treated with antifungal treatment without the need for surgery. It is noteworthy to mention here that fungal culture or molecular biology tests should be performed for further confirmation and definitive diagnosis. These were, however, not performed in the present case, as the fungal infection was not suspected during colonoscopy and all samples were submitted in formalin for histopathologic examination. A more specific and pragmatic approach to managing similar cases in the future is shown in Figure 4.

A key strength of this report is the timely diagnosis made via colonoscopic biopsy, which spared the patient from unnecessary surgical intervention, followed by successful antifungal treatment. The case adds to the limited global data on GIB and reinforces the diagnostic value of tissue sampling in patients with atypical ileocecal masses.

However, this case report also has limitations. Fungal culture, considered the gold standard for specific diagnosis, was not performed. Additionally, a follow-up colonoscopy to assess endoscopic clearance of the lesion was not possible as the patient refused to undergo repeat colonoscopy. Despite these limitations, the case contributes valuable clinical insight into the non-surgical treatment approach for GIB and highlights the need for increased diagnostic awareness. It is very important to note that a timely diagnosis will enable successful treatment with antifungals without the need for surgery. By sharing this case, we aim to raise awareness of GIB among clinicians, to make timely and accurate diagnoses, and improve patient outcomes in the future.

In conclusion, this case highlights the need to include GIB in the differential diagnosis of cases presenting with abdominal pain and a mass lesion in an immunocompetent patients from endemic areas. The case also highlights the importance of early diagnosis and appropriate antifungal therapy to avoid unnecessary surgery. It adds to the growing evidence supporting medical management over surgical intervention in uncomplicated cases.

| 1. | El-Shabrawi MH, Kamal NM, Kaerger K, Voigt K. Diagnosis of gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis: a mini-review. Mycoses. 2014;57 Suppl 3:138-143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Zia Hashmi KH, Hameed Z, Mamoon N. The gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis, a rare entity: Case report and review of literature. J Pak Med Assoc. 2023;73:399-401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Rizk RC, Yasrab M, Weisberg EM, Fishman EK. Gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis masquerading as cancer. Radiol Case Rep. 2024;19:944-948. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Vikram HR, Smilack JD, Leighton JA, Crowell MD, De Petris G. Emergence of gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis in the United States, with a review of worldwide cases. Clin Infect Dis. 2012;54:1685-1691. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Pezzani MD, Di Cristo V, Parravicini C, Sonzogni A, Tonello C, Franzetti M, Sollima S, Corbellino M, Galli M, Milazzo L, Antinori S. Gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis: An emerging mycosis difficult to diagnose but curable. Case report and review of the literature. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2019;31:101378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Meeralam Y, Basfar AM, Alzanbagi A, Tashkandi A, Al Harthi W, Saba F, Khairo M, Alzhrani S, Shariff M. Gastrointestinal Basidiobolomycosis: A Case Series. Cureus. 2024;16:e55008. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Albishri A, Shoukeer MA, Khalid shreef, Hader H, Mazhar Ashour MH, Alsherbiny H, Ghazwani E, Alkedassy K. Gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis. J Pediatr Surg Case Rep. 2020;55:101411. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Gugnani HC. A review of zygomycosis due to Basidiobolus ranarum. Eur J Epidemiol. 1999;15:923-929. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 86] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ejtehadi F, Anushiravani A, Bananzadeh A, Geramizadeh B. Gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis accompanied by liver involvement: a case report. Iran Red Crescent Med J. 2014;16:e14109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | van den Berk GE, Noorduyn LA, van Ketel RJ, van Leeuwen J, Bemelman WA, Prins JM. A fatal pseudo-tumour: disseminated basidiobolomycosis. BMC Infect Dis. 2006;6:140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Balkhair A, Al Wahaibi A, Al-Qadhi H, Al-Harthy A, Lakhtakia R, Rasool W, Ibrahim S. Gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis: Beware of the great masquerade a case report. IDCases. 2019;18:e00614. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ravindranath A, Pai G, Sen Sarma M, Srivastava A, Lal R, Agrawal V, Marak R, Yachha SK, Poddar U, Prasad P. Gastrointestinal Basidiobolomycosis: A Mimic of Lymphoma. J Pediatr. 2021;228:306-307. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Mohammadi R, Ansari Chaharsoghi M, Khorvash F, Kaleidari B, Sanei MH, Ahangarkani F, Abtahian Z, Meis JF, Badali H. An unusual case of gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis mimicking colon cancer; literature and review. J Mycol Med. 2019;29:75-79. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Pouladfar G, Jahangiri S, Shahpar A, Nakhaie M, Nezhad AM, Jafarpour Z, Dashti AS. Navigating treatment for basidiobolomycosis: a qualitative review of 24 cases. BMC Infect Dis. 2024;24:816. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Edington GM. Phycomycosis in Ibadan, Western Nigeria. Two postmortem reports. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1964;58:242-245. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | El-Shabrawi MHF, Kamal NM. Gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis in children: an overlooked emerging infection? J Med Microbiol. 2011;60:871-880. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Mohammed M, Albishri A, Alabbas A, Abdelmogeit SE, Alasmari BG, Alqahtani JA, Mohammed SE, Hawan A, Hussein M, Saeed M, Hamid Y, Ghazwani E. Gastrointestinal Basidiobolomycosis in Pediatric Cases With Multiple-Site Involvement: A Case Series. Cureus. 2024;16:e76451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Alsaeed M, Mursi M, Bahloul A, Alrumeh A, Arab N, Alrasheed M. A rare case of fatal gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis. IDCases. 2023;31:e01709. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Almoosa Z, Alsuhaibani M, AlDandan S, Alshahrani D. Pediatric gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis mimicking malignancy. Med Mycol Case Rep. 2017;18:31-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Mirmoosavi S, Salehi M, Fatahi R, Arero AG, Kamali Sarvestani H, Azmoudeh-Ardalan F, Salahshour F, Safaei M, Ghaderkhani S, Alborzi Avanaki F. Gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis - A rare fungal infection: Challenging to diagnose yet treatable - Case report and literature review. IDCases. 2023;32:e01802. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Alabdan L, Amer SM, Alnabi Z, Alhaddab N, Almustanyir S. Gastrointestinal Basidiobolomycosis in a 45-Year-Old Woman. Cureus. 2020;12:e12109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Parisio EM, Camarlinghi G, Nardone M, De Carolis E, Mattei R, Sanguinetti M. Gastrointestinal basidiobolomycosis in a patient suffering from duodenal ulcer with perforation: First case report from Italy. New Microbiol. 2019;42:125-128. [PubMed] |

| 23. | Geramizadeh B, Heidari M, Shekarkhar G. Gastrointestinal Basidiobolomycosis, a Rare and Under-diagnosed Fungal Infection in Immunocompetent Hosts: A Review Article. Iran J Med Sci. 2015;40:90-97. [PubMed] |

| 24. | Stanley SL Jr. Amoebiasis. Lancet. 2003;361:1025-1034. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 915] [Cited by in RCA: 829] [Article Influence: 36.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Gryseels B, Polman K, Clerinx J, Kestens L. Human schistosomiasis. Lancet. 2006;368:1106-1118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1526] [Cited by in RCA: 1559] [Article Influence: 78.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/