INTRODUCTION

Diabetes mellitus continues to be a growing problem throughout developed, developing and underdeveloped countries[1]. In 2021, 537 million adults aged 20–79 years worldwide (10.5% of all adults in this age group) had diabetes, and by 2030, 643 million (11.3%) and by 2045, 783 million (12.2%) adults (20–79 years) are projected to be living with diabetes[2,3]. The continuously increasing prevalence of diabetes will be accompanied by a greater incidence of diabetic foot ulcers (DFUs), which is one of the most devastating and costly complications[4]. Multiple factors contribute to the development of DFU, including long-term hyperglycemia, neuropathy, peripheral vascular disease, abnormalities in inflammatory response, metabolic disorders, anatomical and molecular changes, and nephropathy[5-8], resulting in delayed or incomplete healing and chronic wounds. Due to the significant amputation rate and mortality related to DFU, effective treatment options are urgently required to salvage limbs, improve patient quality of life and reduce the costs of treatment[9].

Aloe vera has been used as a traditional therapeutic agent for wound healing in China, Egypt and Greece for > 2000 years[10]. Acemannan is an important active polysaccharide in Aloe vera, and has been proved to have multiple functions, including anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory and anticancer activities, wound healing, and amelioration of metabolic diseases[11,12]. In previous studies, our group obtained an acemannan-enriched glycolipid sphere dressing that we named AVBER (Aloe vera barbadensis extract R). Subsequently, we demonstrated that acemannan extracted from Aloe barbadensis exhibited biological safety, immunomodulation and anticancer properties[13]. In the zebrafish fin wounding model, we found that AVBER significantly enhanced tail fin regeneration, ascribed to its ability to induce proliferation and macrophage extravasation in the wounded tail fin[14,15]. Here, we report the case of a patient with DFU treated with AVBER, a promising aloe-gel-derived dressing product for DFU with effective wound healing and limb salvage. Written informed consent for the publication of data and images was provided by the patient.

CASE PRESENTATION

Chief complaints

An 80-year-old female presented to our clinic with the chief complaint of a persistent nonhealing wound on the left dorsal foot, swelling and pain in the left foot, and difficulty in walking.

History of present illness

The symptoms initially presented 18 months ago with an ulcer on the dorsum of the left foot that failed to heal completely. The patient reported attempting multiple treatment modalities, including antibiotics, negative pressure wound therapy, application of epidermal growth factor, and debridement. However, due to suboptimal glycemic control, the ulcer progressively worsened. Prior to visiting our clinic, the patient was advised to consider amputation as a treatment option.

History of past illness

The patient was diagnosed with type 2 diabetes 20 years ago, and suffered from repeated left foot DFU after being injured 15 years ago. She had several hospitalizations due to acute infection and high blood glucose levels. The patient had been taking metformin and gliclazide orally and insulin therapy and herbal hypoglycemic agents for some time, but her blood glucose levels were high and fluctuating, with fasting blood glucose levels of approximately 20 mmol/L.

Personal and family history

The patient had a history of bilateral cataract surgery but no history of smoking or drinking. The patient denied any family history of malignant tumors.

Physical examination

The patient first visited our clinic on December 13, 2019, presenting with DFU on the left second and third toes and the dorsal foot, accompanied by redness and swelling of the distal limb below the ankle. There was a large pustule on the entire third toe and some smaller purulent spots on the dorsal foot, along with yellow, purulent and malodorous exudation. The patient’s dorsal artery of the foot could be palpated, but the pulses were not palpated. The distal part of left ankle was warm and blackish red compared to other body areas, while the first and fifth toes were cooler and paler than other parts of the foot. Both feet had reduced sensitivity to touch and pain, and the toenails were yellow and thickened, with the condition being more severe in the left foot (Figure 1A).

Figure 1 Pathological changes of left diabetic foot ulcer after treatment.

A: December 13, 2019 (before treatment); B: December 29, 2019; C: January 23, 2020; D: February 20, 2020; E: April 8, 2020; F: May 30, 2020.

Laboratory examinations

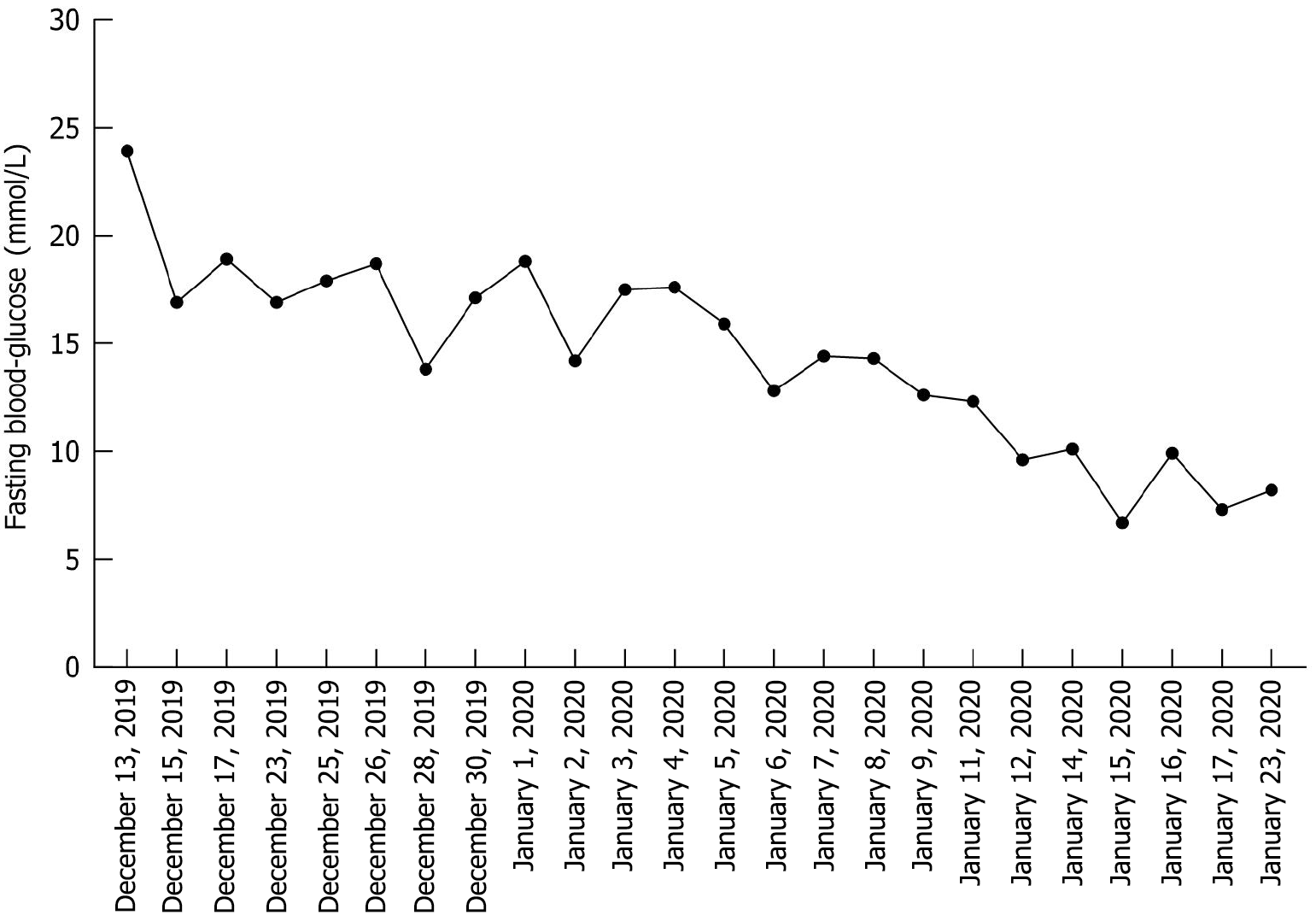

The fasting blood glucose level was 23.9 mmol/L (Roche Accu-Chek Performa System).

Imaging examinations

Not applicable (not performed).

TREATMENT

AVBER was first applied externally on the distal left leg, including the whole calf, dorsal and plantar foot, except the wound area, five times per day. To maintain the active structure of the aloe gel, we indicated that AVBER should be applied without debridement, washing or antiseptics. After scab formation, the application was reduced to three times per day. The patient was instructed to avoid applying pressure on the impaired foot to prevent fractures or other injuries. In addition, management of the patient’s lifestyle and diet was considered to be important. We suggested that the patient maintain a healthier lifestyle and take fresh and whole food instead of industrially packaged and processed food, which might contain a lot of misfolded molecules and heavy metals. Lastly, due to the impossibility of the patient visiting our clinic face-to-face every day, we set up an online chat group including doctors, nutritionists, dieticians, nurse specialists, assistants, as well as the patient and her caregivers for prompt medical assistance from home through telemedicine. Through both face-to-face and online modalities, the patient could receive consultation, regimens, and encouragement immediately, which was essential for the successful treatment outcome.

OUTCOME AND FOLLOW-UP

After 15 days of treatment (December 29, 2019), scabs began to form on the surface of the left dorsal foot. The red and swollen area had reduced to the distal two-thirds of the foot (Figure 1B). The patient felt a little more pain in the wound. The blood glucose levels had improved to approximately 15 mmol/L. We advised her to stop taking gliclazide. After that, the wound and blood sugar level continuously improved. On January 23, 2020, there was a large scab on the dorsal foot, and the patient felt pain relief and exudation was reduced. The redness, swelling and odor reduced, and the periwound skin condition improved (Figure 1C). Her blood sugar levels were better and had reduced to 7.5 mmol/L. We also advised her to stop taking metformin. On February 20, 2020 (Figure 1D), the wound progressively improved. The wound had sealed, most of the scab had been shed, and the skin beneath the scab was fresh and pink, with no swelling. Instead of pain, the patient felt itching on the surface and internal part of the foot. She could walk independently. On April 8 (Figure 1E), the scab was completely shed. There were distinct scars on the surface of the left dorsal foot, but the skin texture, follicles and hairs were observed. She was able to walk normally. Finally, on May 30 (Figure 1F), the wound had regenerated completely with no scarring. Sensitivity to touch and pain in both feet had improved. The toenails of the left foot were still yellow and thickened. The patient had stopped all hypoglycemic drugs for 4 months, and her blood glucose levels were stable at 6.0–7.5 mmol/L (Figure 2). During the follow-up period of 2 years, monitoring showed no recurrence of the patient's disease.

Figure 2

Changes in fasting blood glucose from December 13, 2019 to January 23, 2020.

DISCUSSION

DFU is the most costly and devastating complication of diabetes, and is considered a major cause (approximately 20%) of hospitalization[16]. This report describes the management of a serious case of DFU in a patient with high blood glucose levels. Through telemedicine, we could implement health management, including monitoring blood sugar and diet, educate the patient and her carers for better implementation and mental encouragement, and collect information. We divided the treatment process into three stages: Initial (exudation phase), middle (scab phase) and final (reconstruction phase). In the first stage, more exudation was observed. Instead of the whole foot, inflammation was gradually limited to the vicinity of the wound. In the second stage, the exudation reduced and a scab gradually began to form until it covered the whole surface of the wound. During this period, it was important to protect the scab and avoid debridement due to granulation underneath it, and to close the wound and block pathogens. When the tissues beneath had recovered, the scab was automatically shed. In the last stage (regeneration and reconstruction), as the scab began to be shed, the tissues underneath were gradually reconstructed, revascularized and regenerated, including regeneration of hair follicles and skin texture. Finally, the wound regenerated completely with no significant scar or functional loss.

Considering the patient's history of unsuccessful antibiotic therapy, neither oral nor intravenous antibiotics were administered during this treatment regimen. Despite this, significant improvement in inflammation was observed during the initial phase of treatment, potentially attributable to the robust anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory effects of acemannan. Research has demonstrated that acemannan, functioning as a natural immunomodulator, effectively regulates the activity of key immune cells, including lymphocytes, macrophages and dendritic cells, while also modulating the expression of proinflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor-α[17,18]. Li et al[14] corroborated that acemannan derived from aloe vera gel can influence macrophage metabolism and function, mitigate cytokine storms, and facilitate the resolution of inflammation. DFUs, as prototypical chronic wounds, are characterized by a persistent inflammatory microenvironment driven by neutrophil and macrophage infiltration, which constitutes a critical obstacle to wound healing[19]. In this case, the application of AVBER may have become the trigger point for breaking the vicious cycle of chronic inflammation and promoting healing.

The entire wound healing process lasted approximately 4 months, followed by an additional month for tissue regeneration and reconstruction. Ultimately, amputation was avoided, and the healed wound exhibited no significant scarring or functional impairments. Sensory functions (including pain and temperature perception), blood circulation, and normal walking ability were all restored, and systemic symptoms such as thirst and fatigue showed marked improvement. These findings align with our previous observations in zebrafish tail fin injury models, diabetic rats, and Bama miniature pig deep second-degree scald models[15]. Further investigation revealed that the unique nonpolar carbon chain structure of acemannan, combined with their acetylation and hydroxylation properties, confers both hydrophobic and hydrophilic characteristics[15]. This dual nature enables AVBER to spontaneously form glycolipid globule micelles, enhancing transdermal absorption. More importantly, AVBER can generate a hydrophobic membrane that reduces biological reaction entropy. This membrane specifically facilitates calcium ion transport and activates Wnt transduction signaling pathways that promote wound healing[14], thereby regulating multiple cell types involved in the healing process. Consequently, during treatment, we refrained from using ointments or disinfectants containing alcohol or other potentially disruptive components on the wound surface to preserve the structural integrity and biological activity of AVBER.

It is noteworthy that, despite discontinuing all hypoglycemic medications for several months, the patient experienced a significant improvement in blood sugar levels. Analysis reveals that lifestyle modifications and dietary management were pivotal factors contributing to this outcome. As highlighted by renowned diabetes reversal expert Dr. Jason Fung, nutritional interventions play a critical role in the prevention and management of type 2 diabetes[20]. In this case, through integrated online and offline medical guidance, the team prioritized enhancing the patient's natural dietary regimen, which contributed to improved glycemic control. Relevant research data demonstrate that achieving stringent blood sugar control significantly enhances the healing rates of DFUs in patients who previously showed poor responses to conventional treatments[21]. Although the synergistic mechanisms between the dietary regimen and AVBER application warrant further investigation, the strong correlation between clinical improvement of DFUs and enhanced glycemic control is evident. During the 2-year follow-up period, the patient remained free of DFU recurrence, representing a highly encouraging outcome.

The treatment of DFUs is particularly challenging due to systemic complications associated with diabetes, such as tissue hypoxia, chronic inflammation and metabolic disorders[22]. Current clinical strategies primarily involve a comprehensive approach combining necrotic tissue debridement, local antibiotic therapy and functional dressings (e.g., hydrogels, hydrocolloids, films and alginates)[23,24]. Negative pressure wound therapy or growth factor therapy may also be used when necessary[25]. However, in this case, the late-stage DFU patient had attempted various treatments, including antibiotics, negative pressure therapy, epidermal growth factors and debridement, yet the wound remained unhealed. In DFU management, the selection of dressings plays a critical role. Recent advancements in tissue engineering and materials science have led to the clinical application of novel biological materials, such as decellularized grafts (allografts and xenografts) and artificial skin[25,26]. Despite their promise, these materials are often expensive and present challenges, including immune rejection risks and imperfect preparation processes[27]. In contrast, traditional wet dressings (e.g., hydrogels, hydrocolloids, films and alginates) remain the primary choice for clinical treatment due to their excellent biocompatibility, degradability, accessibility and cost-effectiveness[24,28]. For instance, hydrogels not only maintain an optimal moist wound environment but also enhance therapeutic efficacy through the incorporation of antibacterial agents or growth factors, demonstrating significant benefits for most DFU cases[29]. Nevertheless, hydrogel dressings exhibit inherent limitations, such as restricted absorption capacity, poor mechanical stability and a tendency to cause exudate accumulation[30]. Additionally, the need to change dressing types according to different stages of wound healing increases treatment costs. Notably, the novel dressing AVBER combines the advantages of traditional wet dressings – maintaining a moist environment and promoting autolytic debridement – with the multifunctional properties of its core component, acemannan, which exhibits antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, immunomodulatory and wound-healing-promoting effects. However, it is important to note that AVBER must avoid contact with detergents during use, a requirement that may somewhat limit its clinical applicability.

In this case, the application of AVBER successfully achieved wound closure and limb preservation, thereby alleviating the patient's economic burden and enhancing her quality of life. In comparison with other costly treatment modalities, AVBER may offer a more cost-effective and efficacious alternative for patients with similar conditions. The positive outcomes observed in this case suggest that AVBER could potentially be applied to other acute and chronic skin wounds, such as burns and pressure ulcers. However, it is important to note that the findings from this single-case report are insufficient to establish the scientific validity and generalization of AVBER. Currently, additional basic research and preclinical studies are being conducted to further elucidate its mechanisms of action. Given the inherent limitations of single-case studies, we plan to initiate a researcher-initiated double-blind trial to systematically investigate the effects and underlying mechanisms of AVBER on diabetic foot ulcer healing.