Published online Feb 26, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i6.1076

Peer-review started: November 20, 2023

First decision: December 15, 2023

Revised: December 30, 2023

Accepted: January 27, 2024

Article in press: January 27, 2024

Published online: February 26, 2024

Processing time: 91 Days and 19.7 Hours

Hip fractures account for 23.8% of all fractures in patients over the age of 75 years. More than half of these patients are older than 80 years. Bipolar hemiarthroplasty (BHA) was established as an effective management option for these patients. Various approaches can be used for the BHA procedure. However, there is a high risk of postoperative dislocation. The conjoined tendon-preserving posterior (CPP) lateral approach was introduced to reduce postoperative dislocation rates.

To evaluate the effectiveness and safety of the CPP lateral approach for BHA in elderly patients.

We retrospectively analyzed medical data from 80 patients with displaced femoral neck fractures who underwent BHA. The patients were followed up for at least 1 year. Among the 80 patients, 57 (71.3%) were female. The time to operation averaged 2.3 d (range: 1-5 d). The mean age was 80.5 years (range: 67-90 years), and the mean body mass index was 24.9 kg/m2 (range: 17-36 kg/m2). According to the Garden classification, 42.5% of patients were type Ⅲ and 57.5% of patients were type Ⅳ. Uncemented bipolar hip prostheses were used for all patients. Torn conjoined tendons, dislocations, and adverse complications during and after surgery were recorded.

The mean postoperative follow-up time was 15.3 months (range: 12-18 months). The average surgery time was 52 min (range: 40-70 min) with an average blood loss of 120 mL (range: 80-320 mL). The transfusion rate was 10% (8 of 80 patients). The gemellus inferior was torn in 4 patients (5%), while it was difficult to identify in 2 patients (2.5%) during surgery. The posterior capsule was punctured by the fractured femoral neck in 3 patients, but the conjoined tendon and the piriformis tendon remained intact. No patients had stem varus greater than 3 degrees or femoral fracture. There were no patients with stem subsidence more than 5 mm at the last follow-up. No postoperative dislocations were observed throughout the follow-up period. No significance was found between preoperative and postoperative mean Health Service System scores (87.30 ± 2.98 vs 86.10 ± 6.10, t = 1.89, P = 0.063).

The CPP lateral approach can effectively reduce the incidence of postoperative dislocation without increasing perioperative complications. For surgeons familiar with the posterior lateral approach, there is no need for additional surgical instruments, and it does not increase surgical difficulty.

Core Tip: We evaluated the effectiveness and safety of the conjoined tendon-preserving posterior (CPP) approach for bipolar hemiarthroplasty (BHA) during a short-term follow-up. We retrospectively evaluated 80 patients who underwent CPP BHA implanted with cementless femoral protheses. We protected the posterior structures of the hip joint. We made a partial incision in the quadratus femoris muscle to increase exposure, thus making the surgical procedure more feasible. There was no dislocation or other adverse events observed during the early follow-up period. The CPP approach can effectively reduce dislocation after BHA and improve postoperative hip joint stability.

- Citation: Yan TX, Dong SJ, Ning B, Zhao YC. Bipolar hip arthroplasty using conjoined tendon preserving posterior lateral approach in treatment of displaced femoral neck fractures. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(6): 1076-1083

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i6/1076.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i6.1076

Hip fractures account for 23.8% of all fractures in patients over the age of 75 years[1]. More than half of these patients are older than 80 years[2]. A substantial proportion of hip fractures are femoral neck fractures, which puts the femoral head at risk of osteonecrosis and nonunion due to the vulnerable blood supply[3]. Bipolar hemiarthroplasty (BHA) was established as an effective management option that results in excellent pain relief, early mobilization, a short operation time, similar revision rate to total hip replacement within 5 years, and good long-term return to function in inactive elderly patients[4,5].

Various approaches can be used for the BHA procedure. The conventional posterolateral approach is the most widely used technique because it provides easy exposure, a short operation time, and a low incidence of postoperative gait disturbances[6]. However, it also leads to a higher postoperative dislocation rate than the anterior and lateral approaches[7,8]. Surgeons modified the posterolateral approach and reduced the incidence of postoperative dislocation by retaining the piriformis tendon and short external rotators with varying degrees[9-11].

Tetsunaga et al[12] reported a BHA technique using the conjoined tendon-preserving posterior (CPP) approach. For this technique, only the external obturator muscle is dissected in geriatric patients. Good outcomes with no cases of postoperative dislocation have been reported. Our department started using the CPP approach for BHA for displaced femoral neck fractures in 2021. This retrospective study was conducted to evaluate the effectiveness and safety of the CPP approach for BHA in elderly patients with femoral neck fractures.

This retrospective cohort study was approved by the institutional review board of our hospital. A prospectively compiled database was used to recruit patients who underwent cementless BHA for a displaced femoral neck fracture at our hospital from February 2021 to May 2022. A total of 103 consecutive patients were identified. One year after the surgery, 23 patients were lost to follow-up or died due to causes unrelated to the BHA. A total of 80 patients were included in this study.

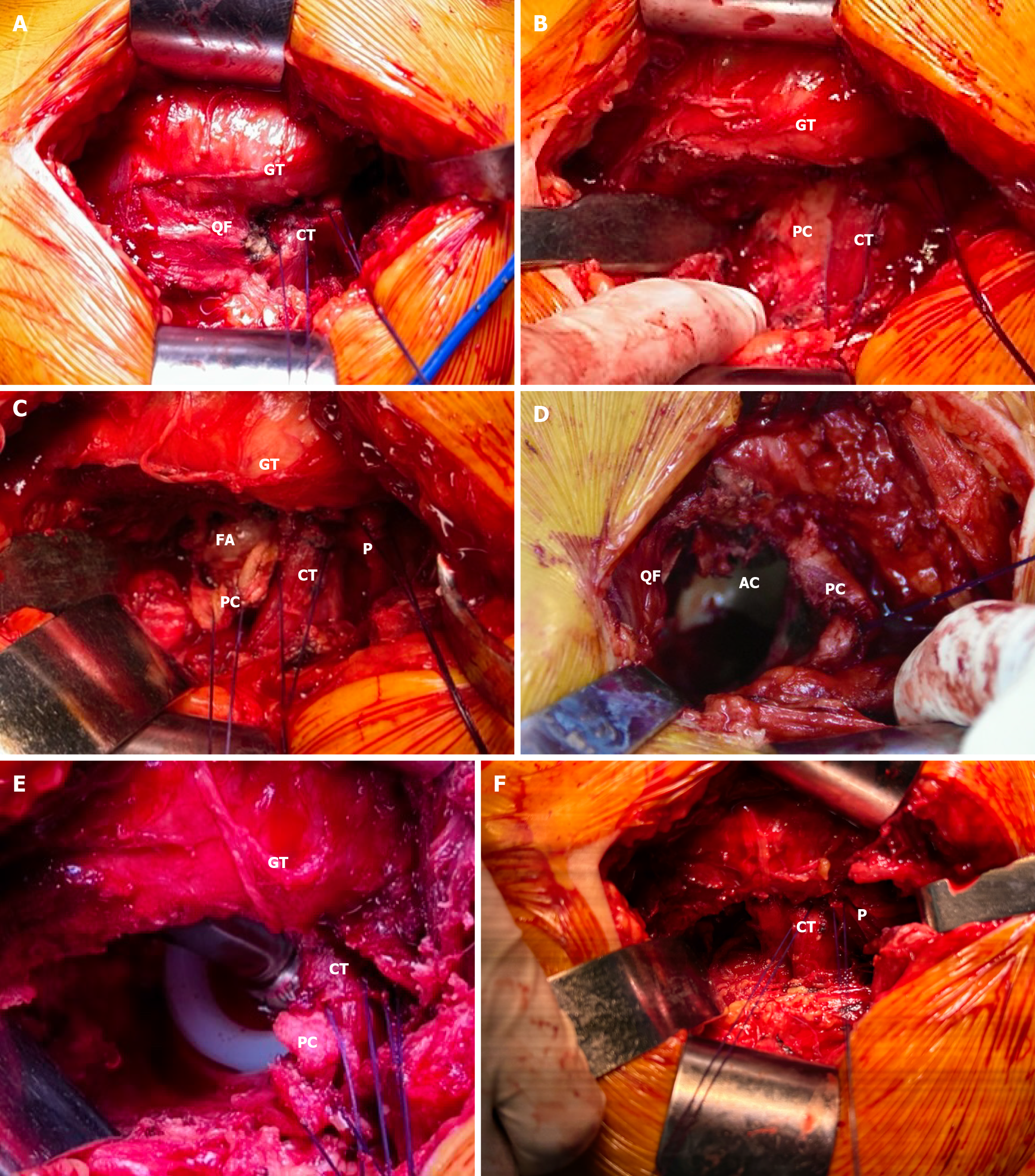

All operations were performed by a single senior surgeon (Yu-Chi Zhao), who performs at least 200 hip arthroplasty surgeries annually. The patients underwent BHA in the lateral decubitus position, and the iliac crest and sacrum were fixed anteriorly and posteriorly, respectively, to obtain a stable pelvis. A 45° incision about 10 cm in length was made posteriorly with the apex of the greater trochanter as the center. The gluteus maximus was bluntly separated along its fibers. Then, self-retaining retractors were placed under the deep fascia layer of the gluteus maximus. The pericapsular fat was resected using electrocautery to expose the posterior margin of the gluteus medius and the short external rotator muscles. The sciatic nerve was identified and protected during the operation. The piriformis tendon was palpable in the superior aspect of the wound deep to the gluteus Medius muscle. The gemellus superior, internal obturator, gemellus inferior, external obturator muscles, and quadratus femoris were identified caudally (Figure 1A). The obturator externus and proximal quadratus femoris were sectioned at the bony insertion site along the posterior aspect of the greater trochanter (Figure 1B).

It is important to coagulate the deep medial circumflex femoral artery, which is almost always at the proximal margin of the quadratus femoris muscle. The inferior portion of the joint capsule was incised in an “L” shape that started from the caudal margin of the gemellus inferior muscle. The arthrotomy was extended distally along the posterior border of the femur while preserving the posterior labrum. Then, No. 1 Ethicon was used to mark and invert the dissected capsule (Figure 1C). After the femoral neck was cut along the planned osteotomy line, the femoral head was removed using a corkscrew (Figure 1D). The femoral head was measured to select the appropriate outer head. The hip joint was flexed, adducted, and internally rotated to manipulate the femur in a similar way to the classical approach. Next, femoral broaching and insertion of instruments and femoral components were performed while preserving the piriformis muscle and conjoined tendon. An inner head and outer head of appropriate lengths were put in place to perform reduction. Manual reduction was performed according to a previous report[12]. This often requires a greater hip flexion degree than the conventional posterolateral approach. Then, the reduction was completed by pushing the outer head to the acetabulum. At this time, the suture on the capsule was retracted to prevent the capsule from embedding into the acetabulum (Figure 1E). After testing the hip stability and determining that there was no discrepancy in leg length, the joint was irrigated by a pulse flusher. The capsule, obturator externus, and proximal quadratus femoris was repaired to the trochanter by two transosseous tunnels, and the proximal capsule incision was repaired side to side (Figure 1F). All patients began full weight-bearing exercises assisted by a walker on postoperative day 1. A pillow was recommended to avoid excessive adduction for 3 wk.

The primary outcome was postoperative dislocation and adverse event rates. We also collected demographic data, including age, sex, and body mass index, perioperative data, including time to operation, operation time, preservation of short external rotator muscles, bleeding volume, transfusion, and the type of the prosthesis used, and postoperative data, including prosthesis alignment and femoral stem subsidence during follow-up. The Health Service System (HSS) score[13] was used to evaluate the hip function.

SPSS software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, United States) was used for statistical analysis, and continuous variables were represented by mean ± SD. The paired t test was used to compare HSS scores before surgery and 1 year after surgery. P values < 0.05 were considered significant.

Among the 80 patients, 57 (71.3%) were female. The time to operation averaged 2.3 d (range: 1-5 d). The mean age was 80.5 years (range: 67-90 years), and the mean body mass index was 24.9 kg/m2 (range: 17-36 kg/m2). According to the Garden classification, 42.5% of patients were type Ⅲ and 57.5% of patients were type Ⅳ.

The mean postoperative follow-up time was 12.3 months (range: 10-18 months). Uncemented bipolar hip prostheses were used for all patients: 31 hips with Self-Centering Bipolar and HA-coated Corail® stem (Depuy, Warsaw, IN, United States); and 49 hips with Cocr Ball Head & Bipolar Head and tapered HA-coated CL stem (AKMEDICAL, Beijing, China). The average surgery time was 52 min (range: 40-70 min) with an average blood loss of 120 mL (range: 80-320 mL).

The gemellus inferior was torn in 4 patients (5%), while it was difficult to identify in 2 patients (2.5%) during surgery. The posterior capsule was punctured by the fractured femoral neck in 3 patients, but the conjoined tendon and the piriformis tendon remained intact. The transfusion rate was 10% (8 of 80 patients). No patients had stem varus greater than 3 degrees or femoral fractures.

There were no patients with stem subsidence more than 5 mm at the last follow-up. There were also no postoperative dislocations throughout the follow-up period. No significance was found between preoperative and postoperative mean HSS scores (87.30 ± 2.98 vs 86.10 ± 6.10, t = 1.89, P = 0.063).

Hemiarthroplasty has been widely used for the treatment of displaced intracapsular fractures of the femoral neck with favorable clinical outcomes[14,15]. However, postoperative dislocation in patients who underwent the conventional posterolateral approach remains a seemingly inevitable complication[8,16]. The lateral approach[6] and direct anterior approach (DAA)[17] were introduced for hemiarthroplasty in recent years. Compared to the posterolateral approach, significantly lower dislocation rates and early functional mobility were observed[18].

Recently, Maratt et al[19] reported that there was no difference in the dislocation rate after total hip arthroplasty (THA) between patients undergoing a DAA (0.84%) and a modern posterior approach with repair of the capsule (0.79%). Christensen et al[20] conducted a retrospective review of 13335 primary THA procedures and found that patients in the posterior approach group had a slightly higher dislocation rate compared to the DAA and lateral groups (1.1% vs 0.7% vs 0.5%, respectively). Differences in dislocation rates for different approaches may be due to improved protocols and surgical techniques, larger bearing heads, and dual mobility constructs to avoid prosthetic impingement and dislocations that have occurred over the past decade. Furthermore, there is still a learning curve for the different approaches, even for surgeons who are already familiar with the posterolateral approach. In addition, perioperative complications such as femoral fracture, nerve palsy, and prosthesis malposition will still inevitably occur in the early stages of the learning curve[21,22].

The conventional posterolateral approach usually requires excision of the insertion point of the piriformis tendon, and short external rotators are released from their insertion on the posterior margin of the greater trochanter. The posterior capsule is incised as far superior and inferior as feasible for exposure of the acetabulum and intraoperative dislocation of the femoral head from acetabulum[23]. Due to instability after surgery, Pellicci et al[24] advocated that posterior soft tissue should be repaired to reduce the dislocation rate. However, Stähelin et al[25] reported that the repair failure rate of short external rotator muscles was as high as 70%. Stangl-Correa et al[26] reported that the incidence of failure of the reinsertion of short external rotators and the posterior capsule was 16.2% based on ultrasound findings conducted 6-8 wk after surgery.

Pellicci et al[27] used magnetic resonance imaging to evaluate the integrity of the posterior soft tissue repair after primary THA. They found that in 90% of patients the posterior capsule remained intact. They also observed that 43% of piriformis tendons and 57% of conjoined tendons had a gap > 25 mm between the hypointense tendon end and the greater trochanter. Additionally, they found atrophy of the piriformis muscle and the obturator internus muscle. The different results from these studies may be due to different assessment methods. However, they demonstrate that there is still a possibility of failure and compromised muscle function even after repair. Therefore, it is better to maintain continuity during surgery instead of repairing after cutting. Maintaining continuity can maintain a greater degree of integrity and physiological function of the soft tissues.

Several authors have reported that the modified posterior approach can preserve some of the short external rotators of the hip. Khan et al[28] reported lower mean blood loss, greater improvement in Western Ontario McMaster Osteo-Arthritis Index scores, and no dislocations for the less invasive approach compared to the standard posterior approach. They preserved the piriformis tendon and released the posterior capsule and tendons of the gemelli and obturator internus. Repair of the posterior capsule was suggested. Kim et al[9] reported excellent results in a series of 220 patients using external rotator preservation, in which they preserved the piriformis, superior gemelli, and obturator internus with complete posterior capsulectomy.

Roger and Hill[10] adopted a posterosuperior approach, which detaches and repairs the piriformis or conjoined tendon. Penenberg et al[29] introduced a percutaneously assisted THA, which is similar to the approach reported by Roger and Hill[10]. These two approaches need specialized instruments to complete the operation procedure. The CPP approach we adopted in this study uses traditional posterior lateral approach instruments without the need for specialized instruments, making it easy to implement in clinical practice. Moreover, surgical records show that the integrity of short external rotator muscles and piriformis tendon is well preserved during surgery, without increasing the exposure difficulty.

For BHA, it is not often necessary to expose the acetabulum like in a THA. In BHA, removing the femoral head, ex

We have performed BHA using the CPP approach since 2021. Two different brands of prostheses have been implanted. Both have reduced shoulder design, which allows the prosthesis to be implanted in a neutral alignment while reducing the risk of injury to the conjoined tendons. In addition to preserving short external rotators and the piriformis tendon, we also focus on preserving the integrity of the posterior upper joint capsule (ischiofemoral ligament). This can form a soft tissue wall that blocks the posterior upper dislocation. Moreover, it can preserve the wrapping effect on the large outer head, which can reduce the abnormal increase in mobility after joint replacement surgery[31]. We do not emphasize the integrity of the quadratus femoris muscle. To avoid damaging the short external rotator muscles, caudal exposure is necessary to make the removal of the femoral head and the procedure of the medullary cavity easier. In addition, electrocoagulation reduces intraoperative blood loss compared to intraoperative blunt injury of the ascending branch of the medial circumflex femoral artery in the quadriceps femoris muscle caused by traction.

Although no cases of postoperative dislocation and femoral fracture were detected, 4 cases of gemellus inferior tears were detected during surgery, which mainly occurred in the early stage. No cases needed total posterior capsulotomy, but we observed puncture of the posterior capsule by the fractured femoral neck in 3 cases. This may be due to the lack of preoperative immobilization, such as transcutaneous traction. Postoperative rehabilitation for these patients was the same as the other patients.

Our study had some limitations. First, our study was retrospective despite using prospectively compiled data. Second, there was no comparative group via conventional posterolateral approach during the same period. Because there is very little risk of posterior dislocation after utilizing the CPP approach, we have avoided performing BHA using the conventional posterolateral approach during the study period. However, the dislocation rate in this study was significantly lower than that at our institution from 2019-2020 [0% (0/80) vs 4.32% (6/139)]. Third, the follow-up time was short. Since dislocation after hip arthroplasty usually occurs within 3 months, the length of follow-up in our study also has some degree of clinical significance.

This retrospective study revealed that the CPP approach for BHA is a safe and effective approach for treatment of femoral neck fractures with fully coated cementless femoral stem. For surgeons who are familiar with the posterolateral approach, no special instrumentation is required and the learning curve is minimal. Compared with the traditional posterolateral approach, the CPP approach can preserve the conjoined tendon, piriformis tendon, and partial posterior joint capsule, providing greater hip stability and significantly reducing the postoperative dislocation rate without increasing perioperative complications.

The traditional posterior lateral approach for hip replacement carries a high risk of hip dislocation. Surgeons have reduced the incidence of dislocation after hip replacement by modifying the surgical approach. Reducing the dislocation rate after bipolar hemiarthroplasty (BHA) surgery will greatly improve patient satisfaction and quality of life.

To improve the stability of the hip joint and reduce the postoperative dislocation rate through modifying the posterior lateral approach by preserving the conjoined tendon, piriformis tendon, and partial posterior joint capsule.

To explore the effectiveness and safety of the conjoined tendon-preserving posterior lateral (CPP) approach for BHA in patients with a fractured femoral neck.

This retrospective study included adult inpatients from single hospital who underwent BHA with the CPP approach. Paired t test was used to compare the Health Service System scores before surgery and 1 year after surgery.

No dislocation was found during the follow-up period. No serious postoperative complications occurred.

The CPP approach can significantly reduce postoperative dislocation after BHA in femoral neck fracture patients.

This study provided evidence for how to reduce the dislocation rate after hip replacement surgery and emphasized the importance of the soft tissue integrity around the hip joint.

| 1. | Veldman HD, Heyligers IC, Grimm B, Boymans TA. Cemented versus cementless hemiarthroplasty for a displaced fracture of the femoral neck: a systematic review and meta-analysis of current generation hip stems. Bone Joint J. 2017;99-B:421-431. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sing CW, Lin TC, Bartholomew S, Bell JS, Bennett C, Beyene K, Bosco-Levy P, Bradbury BD, Chan AHY, Chandran M, Cooper C, de Ridder M, Doyon CY, Droz-Perroteau C, Ganesan G, Hartikainen S, Ilomaki J, Jeong HE, Kiel DP, Kubota K, Lai EC, Lange JL, Lewiecki EM, Lin J, Liu J, Maskell J, de Abreu MM, O'Kelly J, Ooba N, Pedersen AB, Prats-Uribe A, Prieto-Alhambra D, Qin SX, Shin JY, Sørensen HT, Tan KB, Thomas T, Tolppanen AM, Verhamme KMC, Wang GH, Watcharathanakij S, Wood SJ, Cheung CL, Wong ICK. Global Epidemiology of Hip Fractures: Secular Trends in Incidence Rate, Post-Fracture Treatment, and All-Cause Mortality. J Bone Miner Res. 2023;38:1064-1075. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 313] [Article Influence: 104.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Miyamoto RG, Kaplan KM, Levine BR, Egol KA, Zuckerman JD. Surgical management of hip fractures: an evidence-based review of the literature. I: femoral neck fractures. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008;16:596-607. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 186] [Article Influence: 10.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Schmidt AH, Leighton R, Parvizi J, Sems A, Berry DJ. Optimal arthroplasty for femoral neck fractures: is total hip arthroplasty the answer? J Orthop Trauma. 2009;23:428-433. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ekhtiari S, Gormley J, Axelrod DE, Devji T, Bhandari M, Guyatt GH. Total Hip Arthroplasty Versus Hemiarthroplasty for Displaced Femoral Neck Fracture: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2020;102:1638-1645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 12.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Kristensen TB, Vinje T, Havelin LI, Engesæter LB, Gjertsen JE. Posterior approach compared to direct lateral approach resulted in better patient-reported outcome after hemiarthroplasty for femoral neck fracture. Acta Orthop. 2017;88:29-34. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Spina M, Luppi V, Chiappi J, Bagnis F, Balsano M. Direct anterior approach versus direct lateral approach in total hip arthroplasty and bipolar hemiarthroplasty for femoral neck fractures: a retrospective comparative study. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2021;33:1635-1644. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Jobory A, Kärrholm J, Hansson S, Åkesson K, Rogmark C. Dislocation of hemiarthroplasty after hip fracture is common and the risk is increased with posterior approach: result from a national cohort of 25,678 individuals in the Swedish Hip Arthroplasty Register. Acta Orthop. 2021;92:413-418. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kim YS, Kwon SY, Sun DH, Han SK, Maloney WJ. Modified posterior approach to total hip arthroplasty to enhance joint stability. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:294-299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Roger DJ, Hill D. Minimally invasive total hip arthroplasty using a transpiriformis approach: a preliminary report. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2012;470:2227-2234. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Yoo JH, Kwak D, Lee Y, Ma X, Yoon J, Hwang J. Clinical results of short external rotators preserving posterolateral approach for hemiarthroplasty after femoral neck fractures in elderly patients. Injury. 2022;53:1164-1168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Tetsunaga T, Tetsunaga T, Yamada K, Sanki T, Kawamura Y, Ozaki T. Bipolar Hip Arthroplasty Using a Conjoined Tendon-preserving Posterior Approach in Geriatric Patients. Acta Med Okayama. 2021;75:25-30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Harris WH. Traumatic arthritis of the hip after dislocation and acetabular fractures: treatment by mold arthroplasty. An end-result study using a new method of result evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1969;51:737-755. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Jonas SC, Shah R, Al-Hadithy N, Norton MR, Sexton SA, Middleton RG. Displaced intracapsular neck of femur fractures in the elderly: bipolar hemiarthroplasty may be the treatment of choice; a case control study. Injury. 2015;46:1988-1991. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Viswanath A, Malik A, Chan W, Klasan A, Walton NP. Treatment of displaced intracapsular fractures of the femoral neck with total hip arthroplasty or hemiarthroplasty. Bone Joint J. 2020;102-B:693-698. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Svenøy S, Westberg M, Figved W, Valland H, Brun OC, Wangen H, Madsen JE, Frihagen F. Posterior versus lateral approach for hemiarthroplasty after femoral neck fracture: Early complications in a prospective cohort of 583 patients. Injury. 2017;48:1565-1569. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 31] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Ferguson TA, Eastman JG. Anterior approach hip arthroplasty. Curr Orthop Pract. 2011;22:39-45. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Neyisci C, Erdem Y, Bilekli AB, Bek D. Direct Anterior Approach Versus Posterolateral Approach for Hemiarthroplasty in the Treatment of Displaced Femoral Neck Fractures in Geriatric Patients. Med Sci Monit. 2020;26:e919993. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Maratt JD, Gagnier JJ, Butler PD, Hallstrom BR, Urquhart AG, Roberts KC. No Difference in Dislocation Seen in Anterior Vs Posterior Approach Total Hip Arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2016;31:127-130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Christensen TH, Egol A, Pope C, Shatkin M, Schwarzkopf R, Davidovitch RI, Aggarwal VK. How Does Surgical Approach Affect Characteristics of Dislocation After Primary Total Hip Arthroplasty? J Arthroplasty. 2023;38:S300-S305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Lee GC, Marconi D. Complications Following Direct Anterior Hip Procedures: Costs to Both Patients and Surgeons. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30:98-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 116] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Nairn L, Gyemi L, Gouveia K, Ekhtiari S, Khanna V. The learning curve for the direct anterior total hip arthroplasty: a systematic review. Int Orthop. 2021;45:1971-1982. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 69] [Article Influence: 13.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | White RE Jr, Forness TJ, Allman JK, Junick DW. Effect of posterior capsular repair on early dislocation in primary total hip replacement. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;163-167. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 183] [Cited by in RCA: 178] [Article Influence: 7.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Pellicci PM, Bostrom M, Poss R. Posterior approach to total hip replacement using enhanced posterior soft tissue repair. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1998;224-228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 320] [Cited by in RCA: 310] [Article Influence: 11.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Stähelin T, Vienne P, Hersche O. Failure of reinserted short external rotator muscles after total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2002;17:604-607. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 26. | Stangl-Correa P, Stangl-Herrera W, Correa-Valderrama A, Ron-Translateur T, Cantor EJ, Palacio-Villegas JC. Postoperative Failure Frequency of Short External Rotator and Posterior Capsule With Successful Reinsertion After Primary Total Hip Arthroplasty: An Ultrasound Assessment. J Arthroplasty. 2020;35:3607-3612. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Pellicci PM, Potter HG, Foo LF, Boettner F. MRI shows biologic restoration of posterior soft tissue repairs after THA. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2009;467:940-945. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Khan RJ, Fick D, Khoo P, Yao F, Nivbrant B, Wood D. Less invasive total hip arthroplasty: description of a new technique. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21:1038-1046. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Penenberg BL, Bolling WS, Riley M. Percutaneously assisted total hip arthroplasty (PATH): a preliminary report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90 Suppl 4:209-220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Nakamura T, Yamakawa T, Hori J, Goto H, Nakagawa A, Takatsu T, Naoki Osamura, Saito A, Keisuke Hagio, Mouri K. Conjoined tendon preserving posterior approach in hemiarthroplasty for femoral neck fractures: A prospective multicenter clinical study of 322 patients. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong). 2021;29:23094990211063963. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | van Arkel RJ, Ng KCG, Muirhead-Allwood SK, Jeffers JRT. Capsular Ligament Function After Total Hip Arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2018;100:e94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ng BW, Malaysia S-Editor: Li L L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zheng XM