Published online Jul 16, 2024. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v12.i20.4427

Revised: May 14, 2024

Accepted: May 22, 2024

Published online: July 16, 2024

Processing time: 86 Days and 0.3 Hours

Benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis (BRIC) is a rare autosomal recessive disorder, characterized by episodes of intense pruritus, elevated serum levels of alkaline phosphatase and bilirubin, and near-normal -glutamyl transferase. These episodes may persist for weeks to months before spontaneously resolving, with patients typically remaining asymptomatic between occurrences. Diagnosis entails the evaluation of clinical symptoms and targeted genetic testing. Although BRIC is recognized as a benign genetic disorder, the triggers, particularly psychosocial factors, remain poorly understood.

An 18-year-old Chinese man presented with recurrent jaundice and pruritus after a cold, which was exacerbated by self-medication involving vitamin B and paracetamol. Clinical and laboratory evaluations revealed elevated levels of bilirubin and liver enzymes, in the absence of viral or autoimmune liver disease. Imaging excluded biliary and pancreatic abnormalities, and liver biopsy de

Our research highlights genetic and psychosocial influences on BRIC, emphasizing integrated diagnostic and management strategies.

Core tip: Benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis (BRIC) is a rare genetic disorder characterized by recurrent episodes of jaundice and pruritus. Our study emphasizes the significance of genetic testing in diagnosing BRIC, particularly in identifying ATP8B1 gene mutations. Additionally, we highlight the impact of psychosocial stressors on BRIC's course, advocating for comprehensive management strategies integrating both genetic insights and psychosocial support.

- Citation: Xu YX, Niu XX, Xu BL, Ji Y, Yao QY. Diagnosis and management of benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis and psychosocial stressors in an adolescent: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2024; 12(20): 4427-4433

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v12/i20/4427.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v12.i20.4427

Benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis (BRIC) is a rare autosomal recessive disorder characterized by intense pruritus, elevated levels of serum alkaline phosphatase (ALP), and bilirubin, alongside near-normal -glutamyl transferase (GGT)[1,2]. Episodes may last from weeks to months, resolving spontaneously, while patients remain asymptomatic between occurrences for extended periods[1,2]. In contrast to progressive liver injuries, BRIC is primarily attributed to genetic mutations[1]. BRIC type 1 is caused by ATP8B1 gene mutations, which lead to ATPase ion pump dysfunction, while BRIC type 2 is associated with ABCB11 gene disruption, which compromises the bile salt export pump function[3]. The diagnosis of BRIC relies on the evaluation of clinical symptoms and targeted genetic testing, with an emphasis on specific mutations in the ATP8B1 or ABCB11 genes as key diagnostic markers for this rare hepatic disorder[4].

Although BRIC is recognized as a benign genetic condition, the specific triggers of its episodes remain elusive, underscoring the necessity for further investigation into psychosocial influences and other contributory factors[4,5]. Factors including stress, hormonal shifts, specific medications, and infections have been associated with symptom intensification, emphasizing the importance of continuous vigilance and research[6-10]. Patients are advised to remain vigilant regarding changes in hormones, stress levels, medication intake, and diet, and to maintain close communication with healthcare professionals for effective symptom management[4].

This case report presents an 18-year-old Chinese male adolescent's journey with recurrent BRIC episodes, illustrating the complex interplay between genetic predispositions and episodic triggers, such as psychosocial stressors, in the etiology of BRIC. Through an in-depth analysis of this case, we emphasize the critical need to integrate these multi

An 18-year-old man was admitted to Zhongshan Hospital Fudan University in September 2020, presenting with a 1-month history of jaundice, accompanied by clay-colored stool, dark-colored urine and pruritus.

The patient's symptoms began 1 mo prior to admission, manifesting as jaundice, clay-colored stool, dark-colored urine and pruritus. Before the onset of these symptoms, he experienced a cold, oral ulcers, loss of appetite, and twice-daily diarrhea, self-medicating with double doses of vitamin B and a regular dose of paracetamol. Despite receiving symp

The patient reported no history of abdominal pain, fever, rash or blood transfusion. There was no record of major illness or surgery in the past. The patient did not have a history of chronic diseases such as diabetes, hypertension or heart disease. There was no history of infectious diseases such as hepatitis B, hepatitis C or HIV/AIDS. The patient had no known allergies to any medication, food or other substances. There was no record of long-term medication use. The patient also had no history of psychological or psychiatric disorders. No other relevant medical history related to the current condition was reported.

The patient did not smoke or consume alcohol. His diet was balanced, preferring light foods, and he engaged in moderate-intensity exercise regularly, working out three or four times a week for about 30 min each session. He had no occupational exposure to harmful chemicals or radiation; his work environment was safe and stable, as he was a student experiencing significant academic pressure. There was no history of similar cases or complaints among his family members. Additionally, there were no known familial diseases or genetic disorders reported. His parents and siblings were in good health, with no history of liver diseases or related symptoms.

On physical examination, he exhibited pronounced jaundice without signs of liver dysfunction, such as palmar erythema and spider angiomas. The liver was palpable just below the right costal margin. The spleen was not palpable, and there was no evidence of free fluid in the abdomen.

The laboratory findings revealed that hemoglobin, total leukocyte count and platelet count were within normal ranges. There was a significant increase in total bilirubin and direct bilirubin levels, recorded at 263.7 μmol/L (normal < 20.4 μmol/L) and 209.1 μmol/L (normal < 6.8 μmol/L) respectively. Aspartate aminotransferase (AST, normal < 40 U/L) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT, normal < 50 U/L) levels were 40 U/L and 27 U/L, respectively. ALP was elevated at 163 U/L (normal: 30–120 U/L), while GGT was within normal limits at 10 U/L (normal: 8–61 U/L). The prothrombin time was 10.2 s (normal < 15 s). Total bile acids exceeded 360 μmol/L (normal: 0–10 μmol/L). Other biochemical parameters, including renal function tests and serum electrolytes, were normal. Tests for hepatitis B surface antigen, antibodies to hepatitis C virus, IgM antibodies to hepatitis A virus, and IgM antibodies to hepatitis E virus were negative. Antinuclear, antimitochondrial, anti-smooth muscle and anti-liver-kidney-microsomal antibodies were within normal ranges. Serum ceruloplasmin and ferritin levels were also normal.

Abdominal ultrasonography findings were normal. Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography demonstrated normal intrahepatic and extrahepatic biliary trees, as well as a normal pancreatic ductal system.

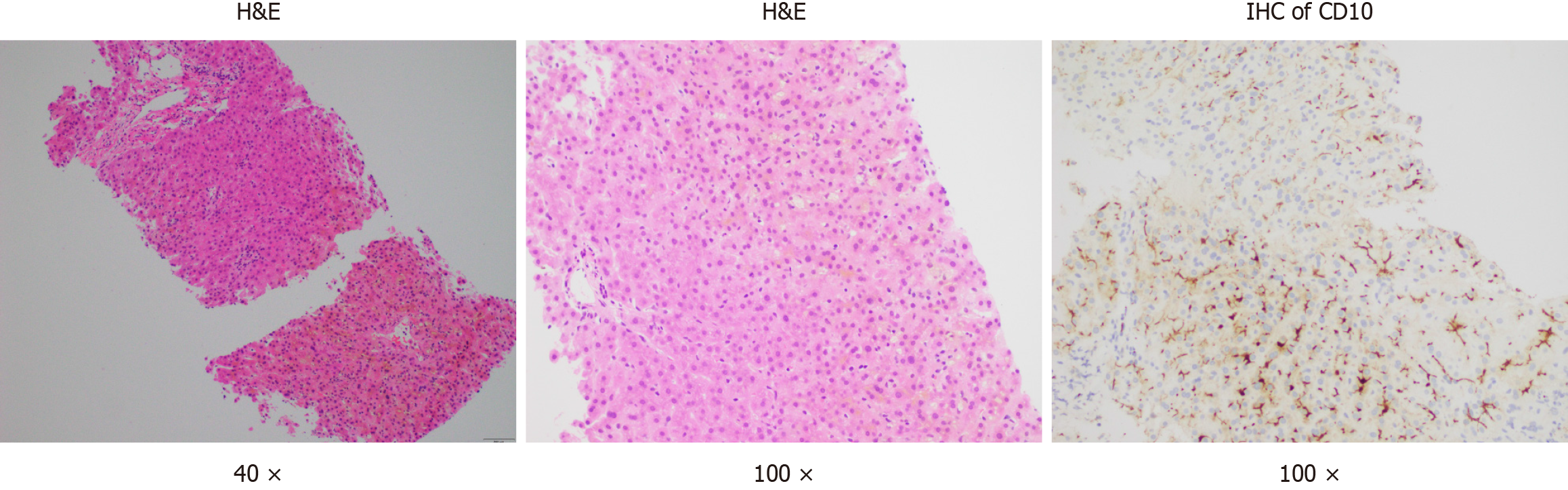

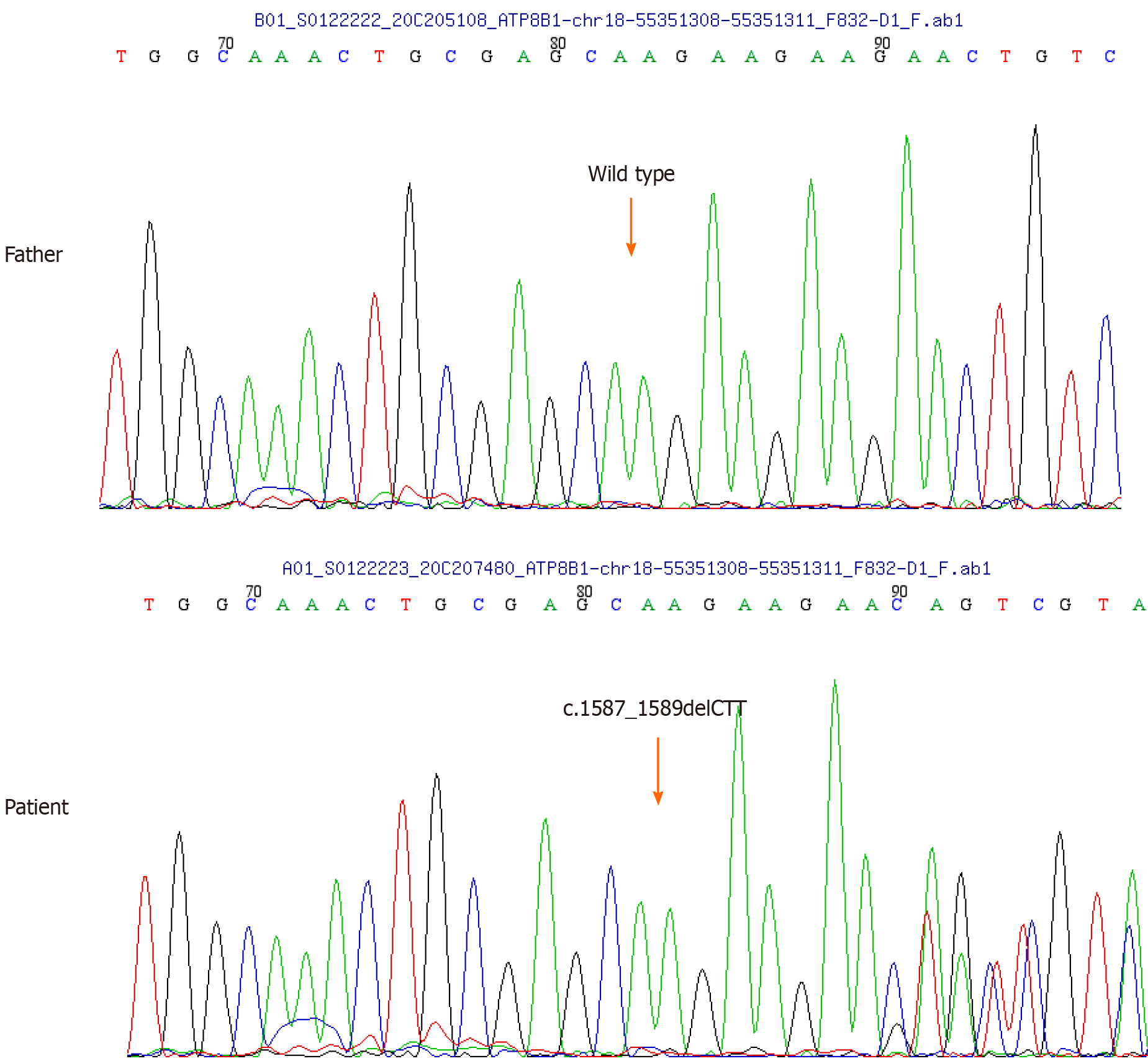

Considering the potential drug-induced liver injury, a liver biopsy was undertaken. The biopsy revealed severe centrilobular cholestasis without significant inflammation or fibrosis. Importantly, the bile ducts were normal, excluding ductal pathology (Figure 1). Owing to clinical suspicion of BRIC, genetic testing for the patient and his parents was advised. Due to the mother's unavailability, only the patient and his father underwent genetic testing for cholestasis-related genes. Conducted by MyGenostics Company in Shanghai, the testing confirmed BRIC by identifying ATP8B1 gene variants, with no mutations in the ABCB11 genes or other relevant genes. A deletion mutation in ATP8B1 gene exon 15 (c.1587_1589delCTT) was identified, resulting in phenylalanine elimination at position 529 (p.F529del) of the protein. This rare heterozygous mutation has a low frequency (0.0001) in the general population (Table 1 and Figure 2). Notably, the father's genetic report showed no relevant mutations.

| Gene | Chromosomal location | Transcription exons | Nucleotide amino acid | Hom/Het | Normal frequency | Pathogenicity analysis |

| ATP8B1 | chr18:55351308-55351311 | NM_005603; exon15 | c.1587_1589delCTT (p.F529del) | Het | 0.0001 | Likely pathogenic |

A comprehensive psychosocial assessment was performed to explore the potential role of psychosocial factors in triggering BRIC episodes. This assessment focused on evaluating the patient's psychological health, life stressors and family dynamics in relation to BRIC episodes. Utilizing the self-rating anxiety scale and the self-rating depression scale, the patient showed mild anxiety and depression. He reported increased stress, anxiety and sadness before BRIC episodes, especially during academic exams and heightened family expectations. His status as a senior high school student and the associated academic pressures were identified as significant stressors. The family dynamics assessment revealed high academic expectations and strict standards from his parents, leading to frequent feelings of criticism and pressure. The assessment indicated that academic and familial pressures may act as psychosocial triggers for BRIC episodes. While a direct causal link cannot be conclusively established, these factors might exacerbate symptoms. Addressing these psychosocial aspects within the treatment plan and providing psychological support are deemed essential.

Diagnostic criteria for BRIC have been proposed by Luketic and Shiffman which include: (1) At least two episodes of jaundice with asymptomatic intervals of months to years; (2) laboratory investigations suggestive of intrahepatic cholestasis; (3) cholestasis-induced severe pruritus; (4) cholangiography showing normal intra- and extrahepatic bile ducts; (5) liver histology suggesting centrilobular cholestasis; and (6) absence of other causes of cholestasis[1]. The key requirements are several episodes of jaundice separated by symptom-free intervals of several months or years and no evidence of an inciting drug, toxin or bile duct disease[11]. Considering the patient's clinical presentation, laboratory findings, imaging examinations, liver biopsy results and genetic testing, the conclusive diagnosis was established as BRIC type 1.

To address the patient's jaundice and intense pruritus, an initial treatment comprising 250 mg UDCA three times daily and 10 mg cetirizine nightly was prescribed. Additionally, based on literature[12], rifampin 150 mg twice daily and phenobarbital 30 mg three times daily were included in the regimen. Although these medications initially alleviated the pruritus, they were discontinued after 1 wk due to significant elevations in AST (296 U/L) and ALT (190 U/L).

Considering the potential impact of psychosocial stressors, comprehensive psychosocial interventions were also implemented to mitigate stress and enhance the patient's psychological health. The interventions included promoting regular physical activity for stress relief and well-being, emphasizing the importance of adequate sleep for mental and physical health, providing dietary advice to foster a balanced diet beneficial for mood and energy, and teaching stress reduction techniques like relaxation exercises and mindfulness meditation. Following this holistic approach, the patient experienced a notable improvement in symptoms within 2 wk.

During his fourth episode of BRIC in March 2021, the patient's total and direct bilirubin levels surged to 88.7 μmol/L and 69.4 μmol/L, respectively (Table 2). His AST and ALT were measured at 64 U/L and 25 U/L, while ALP was elevated at 162 U/L, with GGT remaining within normal limits. Notably, this episode coincided with a period of intense academic stress as the patient faced critical exams, leading to significant pressure from both personal ambition and educational expectations. Recognizing the potential link between such stress and the exacerbation of BRIC symptoms, a comprehensive approach encompassing stress management and the enhancement of a supportive educational and social environment was adopted. The continuation of UDCA treatment, combined with these supportive interventions, led to a notable improvement in the patient's condition within 1 mo.

| Attack | Date | Total bilirubin max (μmol/L) | ALP max (U/L) | GGT (U/L) | Treatment | Duration |

| 1 | October, 2019 | 93.1 | 265 | Normal | UDCA, diammonium glycyrrhizinate | 8 wk |

| 2 | April, 2020 | 64.5 | 156 | Normal | UDCA, diammonium glycyrrhizinate | 6 wk |

| 3 | August, 2020 | 279.0 | 151 | Normal | UDCA, antihistamines, rifampicin | 11 wk |

| 4 | March, 2021 | 88.7 | 166 | Normal | UDCA | 6 wk |

This case of BRIC underscores the vital role of genetic testing in diagnosis and sheds light on the impact of psychosocial factors on the disease course. The patient's improvement, achieved through a combination of pharmacological treatment and targeted psychosocial interventions, underscores the importance of a comprehensive management approach that addresses both the biological and environmental aspects of BRIC.

Intrahepatic cholestasis is characterized by impaired bile flow and the accumulation of bile components within the liver, presenting a multifaceted condition[2]. The clinical presentation of this disorder is closely linked to genetic anomalies, especially in genes responsible for bile acid transport and regulation[2]. Despite being considered a benign genetic disorder, a comprehensive understanding of the etiology of BRIC is still lacking. Genetic studies have pinpointed a mutation in the ATP8B1 gene as the underlying cause of the disorder[13]. Microsatellite haplotype analysis has revealed that the defective ATP8B1 gene is located on the long arm of chromosome 18q21-22[13]. The ATP8B1 gene encodes the familial intrahepatic cholestasis 1 (FIC1) protein[14,15]. Mutations in the ATP8B1 gene and the resultant alterations in the FIC1 protein are implicated in two other forms of familial intrahepatic cholestasis: progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis type I (PFIC1), also known as Byler’s disease, and Greenland familial cholestasis (GFC)[14,15]. The ATP8B1 gene mutations manifest at different loci across these disorders[14]. In PFIC1 and GFC, mutations occur in highly conserved regions of the ATP8B1 gene, which are critical for FIC1 protein functionality[14]. Conversely, mutations in BRIC patients are found in nonconserved genome regions, coding for noncritical parts of the FIC1 protein.

Following variant pathogenicity assessment guidelines, we identified a heterozygous variant in the ATP8B1 gene in our patient, characterized by an in-frame deletion of a single amino acid (c.1587_1589delCTT). The absence of this variant from major public databases, such as the Human Gene Mutation Database, Human Genetic Variation Database, and The Genome Aggregation Database, coupled with strong evidence of pathogenicity from computational predictive analyses, led to its classification as a novel pathogenic variant[16,17]. Novel heterozygous pathogenic ATP8B1 variants, as reported in case studies by Suzuki and Bing, shed light on the variability of BRIC1 presentation and the potential impact of haploinsufficiency on its pathogenesis[18,19]. These reports highlight the critical role of genetic heterogeneity in devising individualized treatment strategies. Our case is consistent with these findings, featuring a novel ATP8B1 mutation in a young BRIC1 patient. Notably, our patient's clinical manifestations mirrored those reported by Suzuki et al[19], including elevated transaminase levels. However, diverging from the classical BRIC1 phenotype described by Luketic and Shiffman, our patient exhibited rapid transaminase elevation, suggesting a potentially unique clinical variant influenced by this specific genetic alteration[1]. This underscores the necessity for comprehensive genetic evaluations in BRIC cases, acknowledging the impact of distinct genetic mutations on clinical manifestations and the importance of personalized treatment approaches.

BRIC is fundamentally a genetic condition characterized by mutations that affect bile acid transport. Nevertheless, our observations suggest that psychosocial stressors, such as academic and familial pressures, may serve as episodic triggers. Research indicates that stress may indirectly impair the normal function of P-type ATPase proteins through multiple pathways, including effects on the neuroendocrine system, inflammatory responses and immune reactions[5]. For instance, the stress-induced release of hormones like adrenaline and cortisol can influence bile synthesis and secretion, potentially contributing to benign cholestasis[5]. Additionally, certain studies indicate that chronic psychological stress can affect liver function, influencing bilirubin metabolism and potentially leading to jaundice[20]. Therefore, considering these factors is critical in the comprehensive management of BRIC. The recurrent BRIC episodes in this patient during periods of heightened stress underscore the importance of integrating psychosocial assessments into routine clinical care. Although establishing a direct causal relationship between psychosocial stress and BRIC exacerbations is beyond the scope of this case report, the implications warrant further exploration. Concurrently, acknowledging the mental health burden is paramount. Integrating counseling and psychoeducational resources to address psychological impacts of BRIC is essential for a holistic treatment approach.

Our case study illuminates the complex nature of BRIC, confirming that although its etiology is rooted in genetic mutations, the role of external factors like psychosocial stress in triggering BRIC episodes is significant. The pivotal role of genetic testing in diagnosing BRIC has been emphasized, serving as the foundation for developing personalized treatment strategies based on each patient's unique genetic and clinical profile. Furthermore, recognizing the potential impact of psychosocial factors on disease progression highlights the need for a comprehensive assessment approach in BRIC patients, ensuring balanced consideration of both genetic predispositions and environmental influences.

We would like to express our gratitude to the patient and their family for their invaluable contribution to this study. Special thanks to the healthcare professionals and colleagues for their support in advancing our understanding of benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis.

| 1. | Luketic VA, Shiffman ML. Benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis. Clin Liver Dis. 2004;8:133-149, vii. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Xie S, Wei S, Ma X, Wang R, He T, Zhang Z, Yang J, Wang J, Chang L, Jing M, Li H, Zhou X, Zhao Y. Genetic alterations and molecular mechanisms underlying hereditary intrahepatic cholestasis. Front Pharmacol. 2023;14:1173542. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Kato K, Umetsu S, Togawa T, Ito K, Kawabata T, Arinaga-Hino T, Tsumura N, Yasuda R, Mihara Y, Kusano H, Ito S, Imagawa K, Hayashi H, Inui A, Yamashita Y, Mizuochi T. Clinicopathologic Features, Genetics, Treatment, and Long-Term Outcomes in Japanese Children and Young Adults with Benign Recurrent Intrahepatic Cholestasis: A Multicenter Study. J Clin Med. 2023;12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Halawi A, Ibrahim N, Bitar R. Triggers of benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis and its pathophysiology: a review of literature. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2021;84:477-486. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ménard C, Pfau ML, Hodes GE, Russo SJ. Immune and Neuroendocrine Mechanisms of Stress Vulnerability and Resilience. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2017;42:62-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 202] [Cited by in RCA: 265] [Article Influence: 29.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lindberg MC. Hepatobiliary complications of oral contraceptives. J Gen Intern Med. 1992;7:199-209. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 70] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Dixon PH, Williamson C. The pathophysiology of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2016;40:141-153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 127] [Article Influence: 12.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Xiao J, Li Z, Song Y, Sun Y, Shi H, Chen D, Zhang Y. Molecular Pathogenesis of Intrahepatic Cholestasis of Pregnancy. Can J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;2021:6679322. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 51] [Article Influence: 10.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Bhogal HK, Sanyal AJ. The molecular pathogenesis of cholestasis in sepsis. Front Biosci (Elite Ed). 2013;5:87-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 45] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Collins SL, Stine JG, Bisanz JE, Okafor CD, Patterson AD. Bile acids and the gut microbiota: metabolic interactions and impacts on disease. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2023;21:236-247. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 680] [Cited by in RCA: 687] [Article Influence: 229.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Tygstrup N, Jensen B. Intermittent intrahepatic cholestasis of unknown etiology in five young males from the Faroe Islands. Acta Med Scand. 1969;185:523-530. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Helgadottir H, Folvik G, Vesterhus M. Improvement of cholestatic episodes in patients with benign recurrent intrahepatic cholestasis (BRIC) treated with rifampicin. A long-term follow-up. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2023;58:512-520. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Nayagam JS, Foskett P, Strautnieks S, Agarwal K, Miquel R, Joshi D, Thompson RJ. Clinical phenotype of adult-onset liver disease in patients with variants in ABCB4, ABCB11, and ATP8B1. Hepatol Commun. 2022;6:2654-2664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 8.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Amirneni S, Haep N, Gad MA, Soto-Gutierrez A, Squires JE, Florentino RM. Molecular overview of progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis. World J Gastroenterol. 2020;26:7470-7484. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (5)] |

| 15. | Bull L, Morotti R and Squires J. ATP8B1 Deficiency. GeneReviews®. 9 Sep 2021. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1297/ Cited 17 March 2023. |

| 16. | Richards S, Aziz N, Bale S, Bick D, Das S, Gastier-Foster J, Grody WW, Hegde M, Lyon E, Spector E, Voelkerding K, Rehm HL; ACMG Laboratory Quality Assurance Committee. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: a joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet Med. 2015;17:405-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26738] [Cited by in RCA: 24797] [Article Influence: 2254.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | gnomAD. The Genome Aggregation Database; 2021 [cited 2023 Mar 17]. Database: The Genome Aggregation Database [Internet]. Available from: https://gwaslab.org/2021/04/24/gnomad/. |

| 18. | Bing H, Li YL, Li D, Zhang C, Chang B. Case Report: A Rare Heterozygous ATP8B1 Mutation in a BRIC1 Patient: Haploinsufficiency? Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:897108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Suzuki H, Arinaga-Hino T, Sano T, Mihara Y, Kusano H, Mizuochi T, Togawa T, Ito S, Ide T, Kuwahara R, Amano K, Kawaguchi T, Yano H, Kage M, Koga H, Torimura T. Case Report: A Rare Case of Benign Recurrent Intrahepatic Cholestasis-Type 1 With a Novel Heterozygous Pathogenic Variant of ATP8B1. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:891659. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Xu MY, Guo CC, Li MY, Lou YH, Chen ZR, Liu BW, Lan L. Brain-gut-liver axis: Chronic psychological stress promotes liver injury and fibrosis via gut in rats. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2022;12:1040749. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/