Published online Feb 6, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i4.945

Peer-review started: October 17, 2022

First decision: December 26, 2022

Revised: December 30, 2022

Accepted: January 12, 2023

Article in press: January 12, 2023

Published online: February 6, 2023

Processing time: 111 Days and 18.4 Hours

Hyperammonemia and hepatic encephalopathy are common in patients with portosystemic shunts. Surgical shunt occlusion has been standard treatment, although recently the less invasive balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration (B-RTO) has gained increasing attention. Thus far, there have been no reports on the treatment of portosystemic shunts with B-RTO in patients aged over 90 years. In this study, we present a case of hepatic encephalopathy caused by shunting of the left common iliac and inferior mesenteric veins, successfully treated with B-RTO.

A 97-year-old woman with no history of liver disease was admitted to our hospital because of disturbance of consciousness. She had no jaundice, spider angioma, palmar erythema, hepatosplenomegaly, or asterixis. Her blood tests showed hyperammonemia, and abdominal contrast-enhanced computed to

Portosystemic shunt-borne hepatic encephalopathy must be considered in the differential diagnosis for consciousness disturbance, including abnormal behavior and speech.

Core Tip: Hyperammonemia and hepatic encephalopathy are common with portosystemic shunts. In this case, hepatic encephalopathy caused by shunting of the left common iliac and inferior mesenteric veins was successfully treated with balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration (B-RTO). A 97-year-old woman was diagnosed with hepatic encephalopathy secondary to a portosystemic shunt. The patient did not improve with conservative treatment: Lactulose, rifaximin, and a low-protein diet. B-RTO was performed, resulting in shunt closure and improvement in hyperammonemia and disturbance of consciousness. The patient was discharged without further consciousness disturbance.Portosystemic shunt-borne hepatic encephalopathy must be considered in the differential diagnosis for consciousness disturbance, including abnormal behavior and speech.

- Citation: Nishi A, Kenzaka T, Sogi M, Nakaminato S, Suzuki T. Treatment of portosystemic shunt-borne hepatic encephalopathy in a 97-year-old woman using balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(4): 945-951

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i4/945.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i4.945

Hepatic encephalopathy is defined as impaired brain function caused by liver insufficiency and/or portosystemic shunt[1]. Portosystemic shunts are known to cause hyperammonemia without liver dysfunction[2]. A portosystemic shunt is a condition in which portal blood flows directly into the systemic circulatory system. In such a condition, ammonia produced in the digestive tract is not metabolized in the liver, resulting in hyperammonemia and hepatic encephalopathy. Treatment methods include medical therapy, surgical shunt occlusion, and shunt embolization with interventional radiology (IVR)[2]. Surgical shunt occlusion or IVR is the treatment of choice when there is no improvement with medical treatment, or when complete cure is desired. In recent years, balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration (B-RTO) has attracted attention owing to its less invasive nature. However, thus far, there have been no reports of B-RTO treatment for cases of portosystemic shunts in very elderly patients, i.e., those aged above 90 years.

In this study, we report a case of hepatic encephalopathy caused by shunting of the left common iliac and inferior mesenteric veins in a 97-year-old patient whose condition improved after B-RTO treatment.

A 97-year-old Japanese woman exhibited abnormal behavior and disorganized speech for 10 d before admission.

Ten days prior to admission, the patient was agitated and spoke incomprehensible words to a neighbor. Her family met her 6 d prior to admission but noticed no unusual behavior or speech. Four days prior to admission, she exhibited strange behavior, saying that she did not know how to eat eggs and walking out with an egg clutched in her hand. Two days prior to admission, she lost spontaneity and had urinary incontinence, which she normally does not have. On the day of admission, her speech was impaired, and her family admitted her to the emergency room of our hospital.

She had a medical history of cholecystectomy and distal gastrectomy for gastric cancer, with no history of liver disease or cognitive dysfunction.

She did not take any medications or consume alcohol. She lived alone and had independent activities of daily living; her food intake and defecation status were unknown.

Upon examination, she was disorientated, only answered “yes” to questions, and could not follow directions. Her vital signs were as follows: Glasgow Coma Scale score, 13 (E4V4M5); blood pressure, 157/111 mmHg; body temperature, 36.6 °C; pulse rate, 100 beats/min; respiratory rate, 20 breaths/min; and oxygen saturation, 99% on ambient air. Physical examination revealed no jaundice, spider angioma, palmar erythema, hepatosplenomegaly, or asterixis.

Blood test results showed elevated serum ammonia levels at 125 μg/dL (normal range: 12-66 μg/dL) (Table 1). Cerebrospinal fluid examination results were normal, and blood cultures were negative.

| Parameter | Recorded value | Standard value |

| White blood cell count | 8500/µL | 3500-8500/µL |

| Hemoglobin | 14.5 g/dL | 12-16 g/dL |

| Platelet count | 16.5 × 104/µL | 12-28 × 104/µL |

| Prothrombin time | 15.2 s | 10-13 s |

| Prothrombin time | 60.8% | 70-130% |

| Activated partial thromboplastin time | 30.8 s | 25.3-37.6 s |

| C-reactive protein | 0.1 mg/L | ≤ 0.5 mg/dL |

| Total protein | 7.1 g/dL | 6.5-8.3 g/dL |

| Albumin | 4.2 g/dL | 3.8-5.3 g/dL |

| Total bilirubin | 1.4 mg/dL | 0.2-1.2 mg/dL |

| Aspartate aminotransferase | 35 U/L | 7-34 U/L |

| Alanine aminotransferase | 22 U/L | 4-43 U/L |

| Lactase dehydrogenase | 299 U/L | 119-229 U/L |

| Alkaline phosphatase | 128 U/L | 38-113 U/L |

| γ-Glutamyl transpeptidase | 16 U/L | 6-30 U/L |

| Blood urea nitrogen | 24 mg/dL | 8-20 mg/dL |

| Creatinine | 0.66 mg/dL | ≤ 0.80 mg/dL |

| Sodium | 145 mEq/L | 139-146 mEq/L |

| Potassium | 4.1 mEq/L | 3.7-4.8 mEq/L |

| Chloride | 109 mEq/L | 101-109 mEq/L |

| Calcium | 9.3 mg/dL | 8.6-10.2 mg/dL |

| Glucose | 102 mg/dL | 70-109 mg/dL |

| TSH | 1.06 μIU/mL | 0.35-4.94 μIU/mL |

| Free T4 | 1.24 ng/dL | 0.70-1.48 ng/dL |

| Cortisol | 20.8 μg/dL | 5.6-21.3 μg/dL |

| Vitamin B1 | 3.0 μg/dL | 2.6-5.8 μg/dL |

| Ammonia | 125 μg/dL | 12-66 μg/dL |

| HBs-Ag | (-) | |

| HCV-Ab | (-) |

Computed tomography (CT) of the head and magnetic resonance imaging showed no abnormalities.

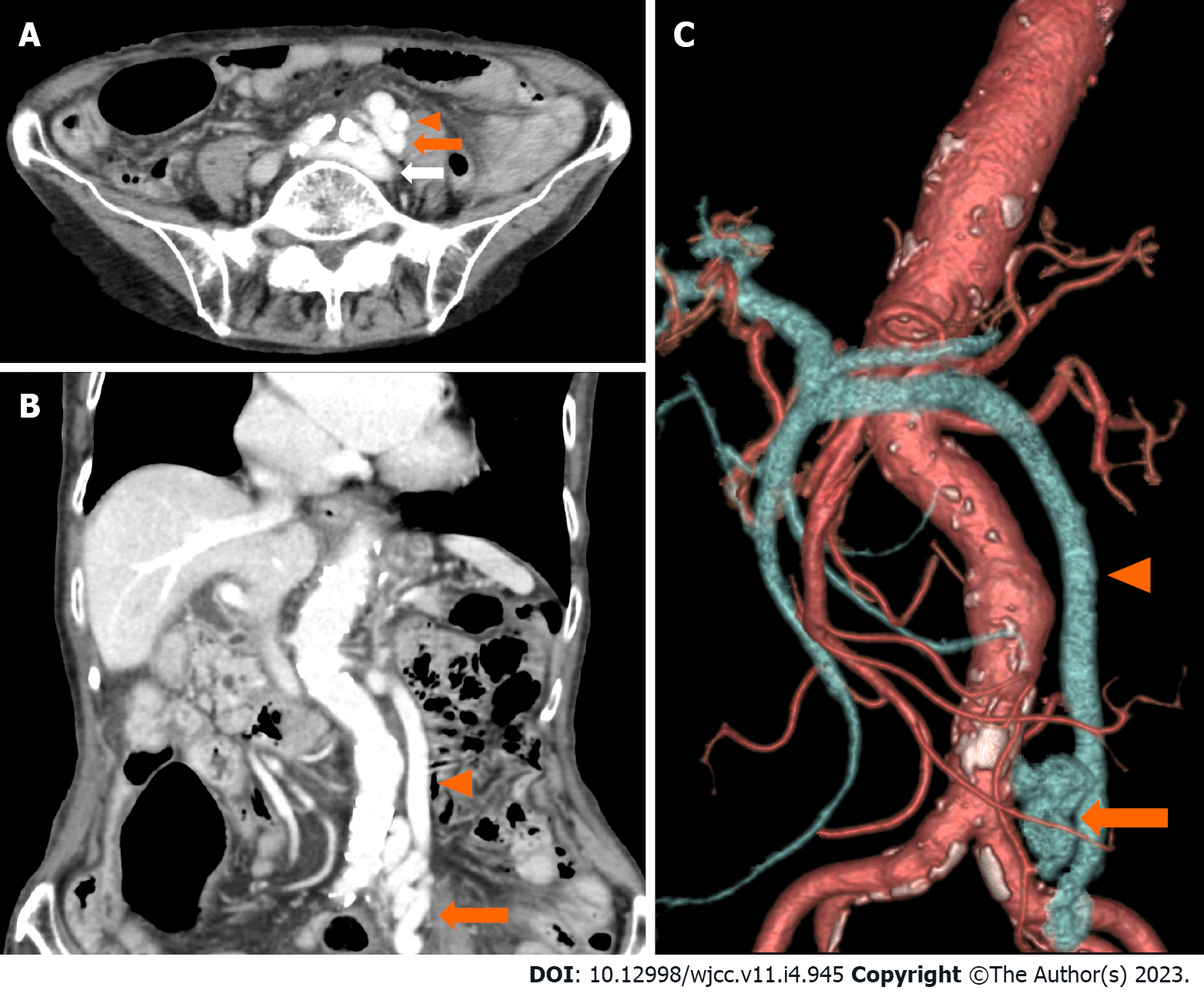

On day 2 after admission, her serum ammonia levels were further elevated to 251 μg/dL and electroencephalography showed triphasic waves. On day 3, an abdominal contrast-enhanced CT scan revealed shunting between the left common iliac vein and the inferior mesenteric vein (Figure 1).

Based on the extent of hyperammonemia and abdominal contrast-enhanced CT findings, a diagnosis of hepatic encephalopathy due to an extrahepatic portosystemic shunt was made.

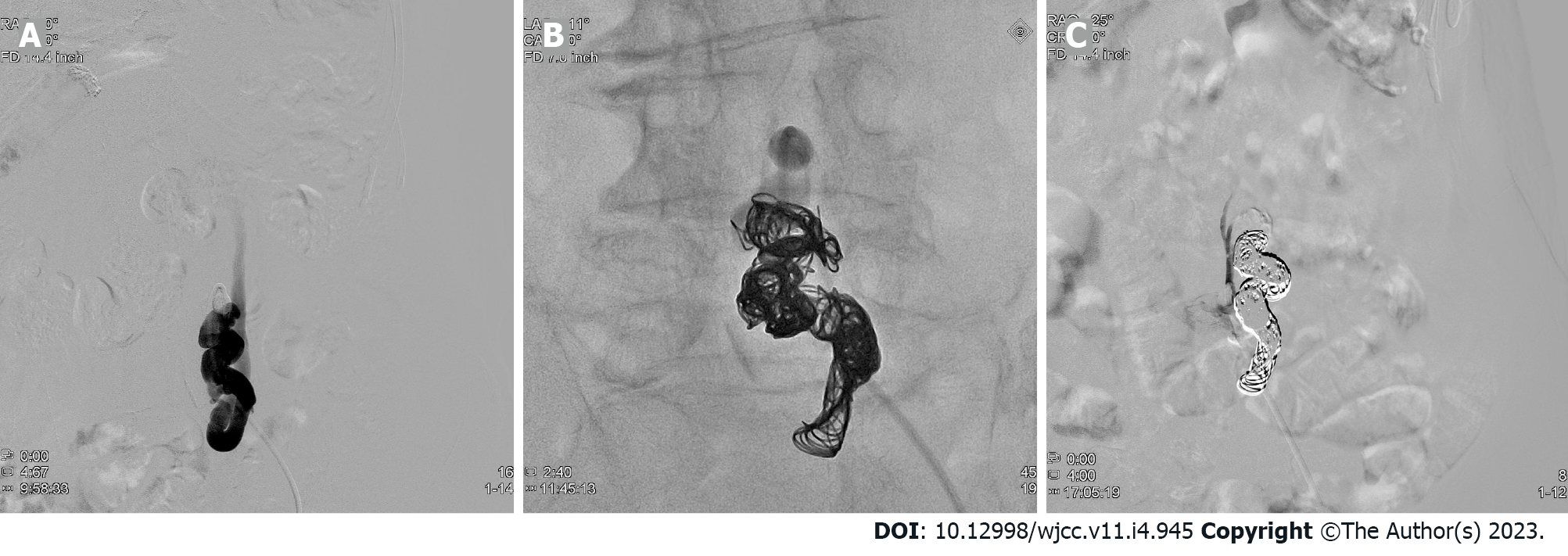

As conservative therapy, 39 g/d oral lactulose was started on day 4, and 1200 mg/d oral rifaximin and a low-protein diet were started on day 13. Her serum ammonia levels decreased to 80 μg/dL on day 14. However, there was little improvement in the patient’s level of consciousness. Therefore, B-RTO was performed under local anesthesia on day 20, and coils were placed in the shunts between the left common iliac vein and the inferior mesenteric vein (Figure 2). On day 21, contrast-enhanced CT confirmed no coil displacement, and shunt closure was achieved. By contrast, mild edematous changes were observed in the descending and sigmoid colons. Moreover, there was a partial thrombus in the inferior mesenteric vein; however, anticoagulants were not administered because of the patient's advanced age. We followed the patient carefully, noting abdominal pain and elevated liver enzymes.

Her level of consciousness improved on day 21 (the day after B-RTO). Her serum ammonia levels were 21 μg/dL on day 28 and remained within the normal range throughout subsequent hospitalizations. There was no abdominal pain or elevated levels of liver enzymes due to complications. The patient was discharged on day 65 without any further disturbance of consciousness.

We report the case of a 97-year-old patient with hepatic encephalopathy due to shunting of the left common iliac and inferior mesenteric veins. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case in which B-RTO was performed for a portosystemic shunt in a very elderly patient aged above 90 years.

On the basis of physical examination, hematology, and imaging findings, this case had no liver dysfunction or cirrhosis. The imaging findings showed shunting of the left common iliac vein and the inferior mesenteric vein, suggesting that the portosystemic shunt was the cause of hepatic encephalopathy. Portosystemic shunts are classified according to their location as type I (intrahepatic), type II (intrahepatic and extrahepatic), type III (extrahepatic), type IV (extrahepatic, portal hypertension), and type V (extrahepatic, absence of the portal vein)[2]. A type III (extrahepatic) portosystemic shunt, to which this case belongs, is the most frequent, accounting for 48.9% of all types, with an average age of onset of 57.4 years[2]. There are congenital and acquired causes of this type of shunt formation, with congenital causes being malformations or retained embryonal vascular vessels and the acquired causes being complications related to abdominal surgery[2]. The patient in this case had a history of cholecystectomy and distal gastrectomy, which may have resulted in the formation of an acquired shunt; however, the cause was difficult to determine because of the lack of comparative images from the past.

Surgical shunt occlusion is the curative treatment for portosystemic shunts; however, it is generally invasive and does not necessarily provide good outcomes[1]. In our case, complications and prolonged hospitalization were concerning. In such cases, IVR is an alternative treatment, and recently cases wherein patients were treated with B-RTO have been reported[3-6]. B-RTO is considered less invasive than surgical treatment, although it may cause complications, such as pleural effusion, ascites, thrombosis, pulmonary embolism, and worsening of esophageal varices[2,7-9]. Anticoagulant administration to elderly patients is particularly challenging owing to the risk of bleeding, and indications should be carefully considered. To the best of our knowledge, the oldest patient who underwent B-RTO for a portosystemic shunt was 86 years old[5]. B-RTO has no age-related restrictions on its indications and does not require special treatment on account of patients’ advanced age[10]. Although this patient was 97 years old, she had no serious comorbidities and was able to perform her daily activities. Therefore, we thought that there was great merit in performing curative treatment and B-RTO.

Hepatic encephalopathy is one of the differential diagnoses of disturbance of consciousness, and it is common to measure serum ammonia levels when there is a history of liver disease or physical findings suggestive of liver dysfunction[11]. By contrast, shock, gastrointestinal bleeding, vesicorectal fistulas, drugs such as valproic acid, and obstructive urinary tract infections caused by urease-producing bacteria may lead to hyperammonemia, even in the absence of liver diseases[12,13]. Portosystemic shunts also cause hyperammonemia[14].

Although there was no history of liver disease or findings suggestive of liver dysfunction in this case, measurement of serum ammonia levels led to diagnosis and subsequent treatment.

This is the first report of B-RTO performed in a patient aged > 90 years with a portosystemic shunt. It is important to consider hepatic encephalopathy due to a portosystemic shunt as a differential diagnosis of disturbance of consciousness, including abnormal behavior and disorganized speech.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: Japan

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B, B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Methawasin K, Thailand; Wang YT, China S-Editor: Chen YL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Chen YL

| 1. | Vilstrup H, Amodio P, Bajaj J, Cordoba J, Ferenci P, Mullen KD, Weissenborn K, Wong P. Hepatic encephalopathy in chronic liver disease: 2014 Practice Guideline by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and the European Association for the Study of the Liver. Hepatology. 2014;60:715-735. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1583] [Cited by in RCA: 1484] [Article Influence: 123.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Watanabe A. Portal-systemic encephalopathy in non-cirrhotic patients: classification of clinical types, diagnosis and treatment. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2000;15:969-979. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 115] [Cited by in RCA: 110] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Asakura T, Ito N, Sohma T, Mori N. Portosystemic Encephalopathy without Liver Cirrhosis Masquerading as Depression. Intern Med. 2015;54:1619-1622. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Yamagami T, Yoshimatsu R, Miura H, Hasebe T, Koide K. Hepatic encephalopathy due to intrahepatic portosystemic venous shunt successfully treated by balloon occluded retrograde transvenous embolization with GDCs. Acta Radiol Short Rep. 2012;1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Miyata K, Tamai H, Uno A, Nakao R, Muroki T, Nasu T, Kawashima A, Nakao T, Kondo M, Ichinose M. Congenital portal systemic encephalopathy misdiagnosed as senile dementia. Intern Med. 2009;48:321-324. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Tanaka O, Ishihara K, Oyamada H, Harusato A, Yamaguchi T, Ozawa M, Nakano K, Yamagami T, Nishimura T. Successful portal-systemic shunt occlusion with balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration for portosystemic encephalopathy without liver cirrhosis. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2006;17:1951-1955. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Shimoda R, Horiuchi K, Hagiwara S, Suzuki H, Yamazaki Y, Kosone T, Ichikawa T, Arai H, Yamada T, Abe T, Takagi H, Mori M. Short-term complications of retrograde transvenous obliteration of gastric varices in patients with portal hypertension: effects of obliteration of major portosystemic shunts. Abdom Imaging. 2005;30:306-313. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Cho SK, Shin SW, Do YS, Park KB, Choo SW, Kim SS, Choo IW. Development of thrombus in the major systemic and portal veins after balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration for treating gastric variceal bleeding: its frequency and outcome evaluation with CT. J Vasc Interv Radiol. 2008;19:529-538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yoshimatsu R, Yamagami T, Tanaka O, Miura H, Okuda K, Hashiba M, Nishimura T. Development of thrombus in a systemic vein after balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration of gastric varices. Korean J Radiol. 2012;13:324-331. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Saad WE, Kitanosono T, Koizumi J, Hirota S. The conventional balloon-occluded retrograde transvenous obliteration procedure: indications, contraindications, and technical applications. Tech Vasc Interv Radiol. 2013;16:101-151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Han JH, Wilber ST. Altered mental status in older patients in the emergency department. Clin Geriatr Med. 2013;29:101-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 110] [Cited by in RCA: 101] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Hawkes ND, Thomas GA, Jurewicz A, Williams OM, Hillier CE, McQueen IN, Shortland G. Non-hepatic hyperammonaemia: an important, potentially reversible cause of encephalopathy. Postgrad Med J. 2001;77:717-722. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kenzaka T, Kato K, Kitao A, Kosami K, Minami K, Yahata S, Fukui M, Okayama M. Hyperammonemia in Urinary Tract Infections. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0136220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Walker V. Severe hyperammonaemia in adults not explained by liver disease. Ann Clin Biochem. 2012;49:214-228. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |