Published online Jan 26, 2023. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i3.662

Peer-review started: October 31, 2022

First decision: November 14, 2022

Revised: December 1, 2022

Accepted: January 5, 2023

Article in press: January 5, 2023

Published online: January 26, 2023

Processing time: 87 Days and 5 Hours

Extraskeletal osteosarcoma (ESOS) is a highly malignant osteosarcoma that occurs in extraskeletal tissues. It often affects the soft tissues of the limbs. ESOS is classified as primary or secondary. Here, we report a case of primary hepatic osteosarcoma in a 76-year-old male patient, which is very rare.

Here, we report a case of primary hepatic osteosarcoma in a 76-year-old male patient. The patient had a giant cystic-solid mass in the right hepatic lobe that was evident on ultrasound and computed tomography. Postoperative pathology and immunohistochemistry of the mass, which was surgically removed, suggested fibroblastic osteosarcoma. Hepatic osteosarcoma reoccurred 48 d after surgery, resulting in significant compression and narrowing of the hepatic segment of the inferior vena cava. Consequently, the patient underwent stent implantation in the inferior vena cava and transcatheter arterial chemoembolization. Unfortunately, the patient died of multiple organ failure postoperatively.

ESOS is a rare mesenchymal tumor with a short course and a high likelihood of metastasis and recurrence. The combination of surgical resection and chemo

Core Tip: Hepatic osteosarcoma is a rare mesenchymal tumor with a short duration and a high likelihood of metastasis and recurrence. Although the imaging examination can help detect lesions, it is difficult to distinguish from other lesions with multiple osteosarcoma-like lesions and make accurate preoperative diagnosis. If hepatic osteosarcoma is suspected, a biopsy and surgery should be performed as soon as possible.

- Citation: Di QY, Long XD, Ning J, Chen ZH, Mao ZQ. Relapsed primary extraskeletal osteosarcoma of liver: A case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases 2023; 11(3): 662-668

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v11/i3/662.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v11.i3.662

Extraskeletal osteosarcoma (ESOS) is a highly malignant osteosarcoma that occurs in extraosseous tissues. It is characterized by a low incidence, invasive growth, a high likelihood of metastasis and recurrence, and a poor prognosis[1]. ESOS often involves the soft tissues of the limbs. Few reports of ESOS occurring in organs are available, and relevant publications are mostly case reports[2,3]. The pathogenesis of ESOS is still unclear. The imaging manifestations of hepatic osteosarcoma are not specific, and its diagnosis depends on pathology and immunochemistry. The treatment of ESOS mainly relies on the combination of surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy.

A 76-year-old male was readmitted to the hospital on September 14, 2020, due to abdominal distension and pain.

The patient had a history of resection of malignancy and had undergone surgery for right hemihepatectomy more than a month prior; however, the patient’s symptoms improved until significant abdominal distension developed a week ago.

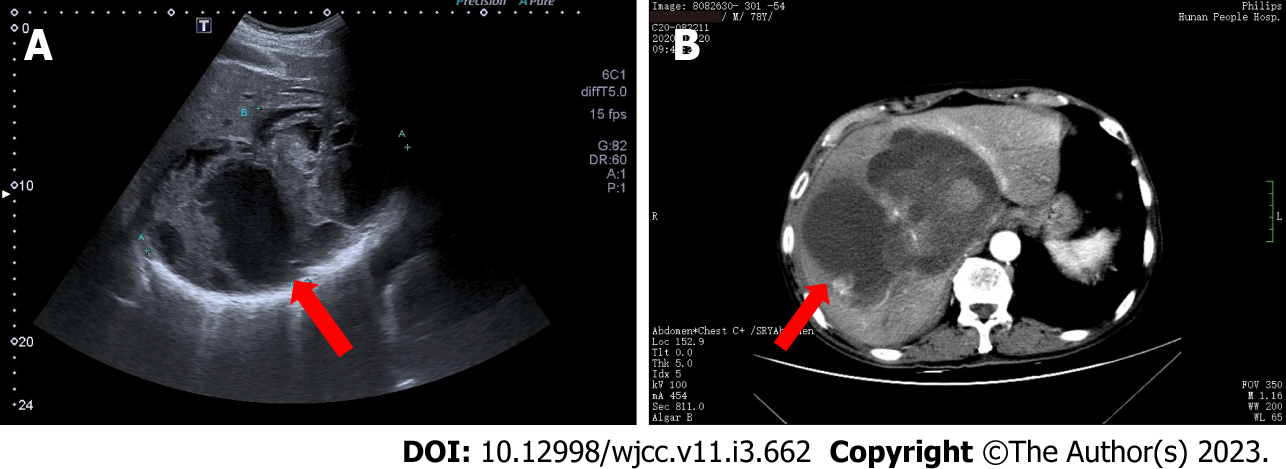

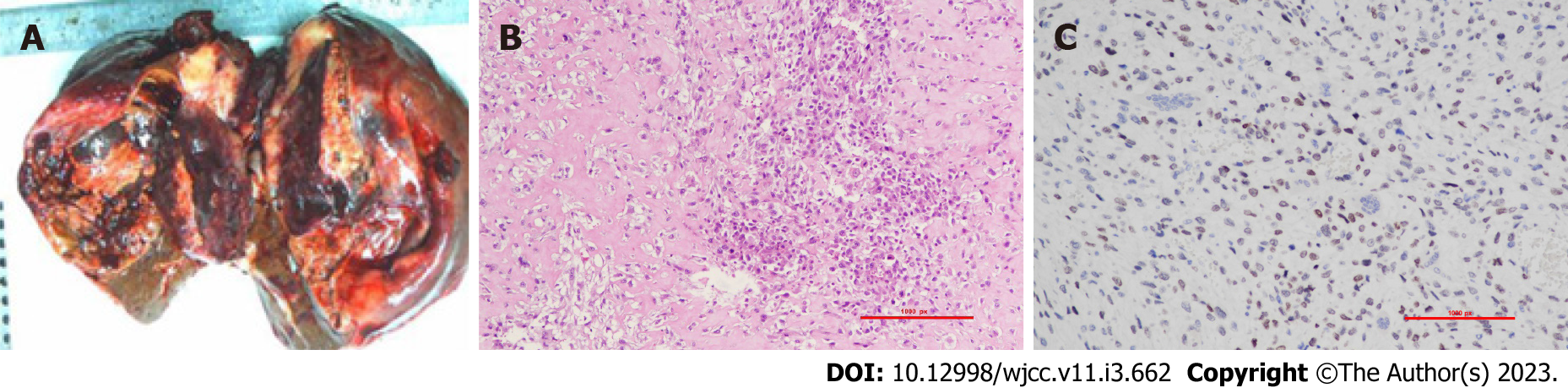

On July 20, 2020, the patient was admitted to the hospital due to aggravation of existing abdominal pain and discomfort. Abdominal color Doppler ultrasound suggested a giant mixed echogenic mass in the right hepatic lobe, and color Doppler flow imaging revealed a small number of blood flow signals in and around the mixed echogenic mass (Figure 1A). Computed tomography (CT) indicated liver enlargement and a giant cystic-solid mass in the right hepatic lobe, and an enhanced scan showed mild to moderate enhancement of the solid component of the mass (Figure 1B). On July 21, 2020, a hospital-wide general consultation was held. After analyzing the patient’s imaging data, laboratory findings, and physical signs, doctors concluded that the large intrahepatic mass was malignant and that a mesenchymal origin was probable; furthermore, the patient was in a hypercoagulable state, and blood clots may occur during or after surgery. Ultimately, doctors who participated in the consultation believed that surgical resection and chemotherapy constituted the best treatment for this patient, as did the patient and his family. On July 28, 2020, the patient underwent right hemihepatectomy. During the operation, a cystic-solid mass was observed in the section of the liver next to the liver capsule. The cystic fluid was already lost, and the grayish-red and grayish-yellow solid areas of the tumor were soft with a cut-fish-like surface (Figure 2A). A rapid intraoperative pathology examination suggested mesenchymal sarcoma. Immunohistochemistry yielded the following results: CK (pan) (-), EMA (-), CD34 (-), S-100 (-), SMA (scattered -), STAT6 (-), Ki67 (+, 30%), SATB2 (partially weak +), p16 (-), CD163 (scattered +), CD68 (scattered +), CD56 (-), desmin (-), and H-Cald (-). Postoperative pathology and immunohistochemistry suggested fibroblastic osteosarcoma (Figures 2B and 2C). The patient received capecitabine monotherapy and was discharged on August 30, 2020.

The patient denied any family history of malignant tumors.

The abdominal muscles of the upper abdomen were slightly tense, tenderness was noted in the right upper quadrant, and percussion pain was evident in the liver area; the abdominal mass was not touched, and an old scar measuring approximately 14 cm long was visible in the right upper quadrant.

Laboratory tests indicated that inflammatory indicators were elevated, and cancer antigen 125 was slightly increased, suggesting poor liver and coagulation functions. In addition, alpha-fetoprotein was 7.86 ng/mL, a hepatitis B virus (HBV) surface antigen test and hepatitis C antibodies were negative, and HBV-DNA was < 1.00E + 02 IU/mL.

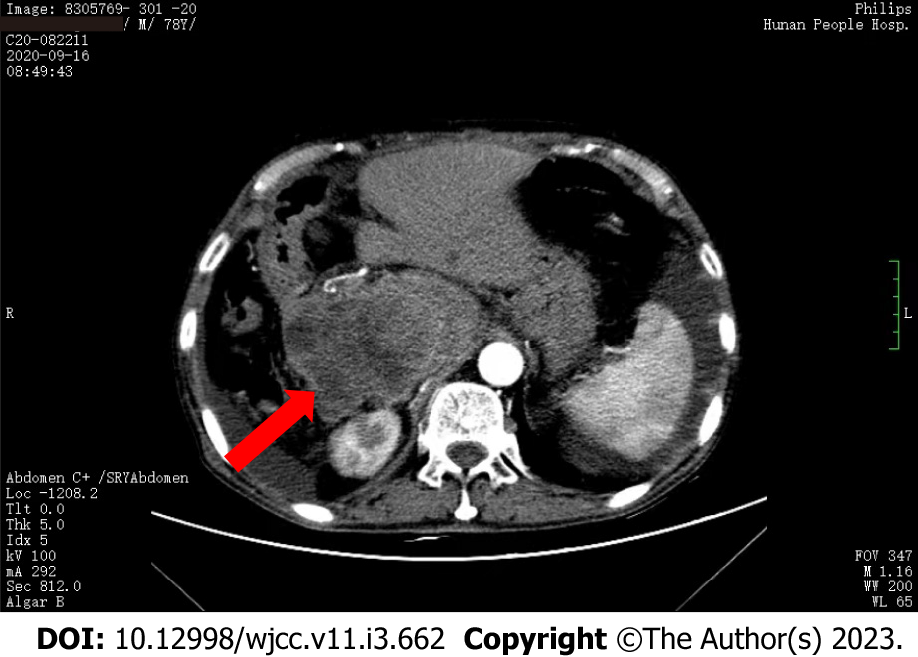

Whole-abdomen nonenhanced and contrast-enhanced CT examinations indicated that the residual liver parenchyma had a patchy lesion with mixed attenuation and apparently uneven enhancement near the inferior vena cava and that the hepatic segment of the inferior vena cava was significantly compressed and narrowed (Figure 3), suggesting tumor recurrence.

Given the patient’s medical history, the final diagnosis was ESOS recurrence.

Considering that the patient had inferior vena cava compression, stenosis, and a large amount of ascites, inferior vena cava stent implantation and transcatheter arterial chemoembolization were carried out on September 22, 2020.

The patient died on September 29, 2020, due to multiorgan failure after surgery.

ESOS is a highly malignant osteosarcoma that occurs in extraosseous tissues. This tumor was first reported in 1941 by Wilson[4]. Its incidence is low, and it occurs primarily in elderly adults. The average age of patients with ESOS is 47.5 to 61 years. ESOS accounts for 1% of all soft tissue sarcomas and 4% of osteogenic osteosarcomas[5]. ESOS is characterized by invasive growth, a high likelihood of metastasis and recurrence, and a poor prognosis[1]. The initial clinical symptom is usually a painless mass[6]. ESOS often involves the soft tissues of the limbs. Few reports of ESOS occurring in organs are available, and most publications are case reports[2,3]. This study reports a primary osteosarcoma occurring on the liver, which is very rare, and only 13 articles were found in the literature search[2,7-18]. Of these patients, ten cases occurred in men, and three occurred in women. Five of the patients had underlying liver cirrhosis. Sumiyoshi and Niho[8] proposed possible tumorigenesis in mesenchymal tissue that proliferates in cirrhosis. However, in our case, the patient had no history of liver cirrhosis or chronic HBV and hepatitis C infection.

The pathogenesis of ESOS is still unclear. Two theories on the pathogenesis of ESOS have been proposed[19]: (1) The tissue residual theory: Residual mesenchymal components from the embryonic development stage form bone and osteosarcomas; and (2) The metaplasia theory: Interstitial fibroblasts in muscle tissues are converted into osteoblasts and chondroblasts in response to internal or external stimuli and then evolve into osteosarcoma. Currently, most scholars support the metaplasia theory. According to their origin, ESOS are classified as primary or secondary ESOS[20]. Primary ESOS occurs in extraskeletal organs and soft tissues and does not attach to the bone or periosteum. No primary ESOS is of bone origin. In contrast, secondary ESOS is mostly metastases from an osteosarcoma of bone origin to the extraskeletal organs and soft tissues or is secondary to certain primary diseases, such as myositis ossificans. In this report, except for the cystic-solid mass in the liver, no evidence of primary tumors or primary bone lesions was found. Therefore, osteosarcomatous foci in other parts of the body were excluded.

Although imaging examinations can help identify lesions, the imaging findings of hepatic osteosarcoma are nonspecific and not different from those of a variety of tumor-like lesions; consequently, hepatic osteosarcoma is difficult to accurately diagnose preoperatively. In this study, the hepatic osteosarcoma manifested as a cystic-solid mass. The histology of hepatic osteosarcoma is similar to that of skeletal osteosarcoma. Although the direct production of osteoid components by osteosarcoma cells has significant diagnostic value, it has no specificity[21]. Pathologists diagnose ESOS based on the appearance of osteoid matrix and osteoblastic-like tumor cells, the differentiation of tumors without fat cells, myogenic or neurogenic properties, and the absence of dedifferentiated or highly differentiated liposarcoma components at specimen crossover and microscopy[22,23]. In this study, immunohistochemistry suggested SATB2 (partially weak+). Special AT-rich sequence-binding (SATB2) is a nuclear matrix-associated protein. SATB2 expression has tissue and stage specificity, and SATB2 is specifically expressed in glandular cells of the lower digestive tract and osteoblasts of bone tumors, which can be used as a marker for differential diagnosis[18]. This case is morphologically consistent with mesenchymal-derived sarcoma, with tumor cells producing a bone-like stroma, combined with positive immunohistochemical SATB2, which is consistent with the diagnosis of osteosarcoma. Therefore, the diagnosis of hepatic osteosarcoma still relies on pathology and immunochemistry.

At present, the treatment of ESOS mainly relies on the combination of surgery, radiotherapy, and chemotherapy. Radical surgery is considered to reduce local recurrence of ESOS but has no obvious inhibitory effect on the distant metastasis of tumors[24]. As adjuvant therapies for ESOS, radiotherapy and chemotherapy are helpful for improving the tumor resection rate and reducing local recurrence and distant metastasis. Since osteosarcoma is a malignant tumor, ESOS has a short course, rapid progression, a high local recurrence rate, and a high risk of distant metastasis[2]. Lee et al[19] reported that the 5-year survival rate of a group of patients diagnosed with ESOS was only 37% and that most of them died within 2 to 3 years after the initial diagnosis. Studies have demonstrated that distant metastasis, large tumors (≥ 10 cm), tumors of the axial skeleton, and advanced age are poor prognostic factors for ESOS, while radiotherapy and chemotherapy have no significant correlation with mortality[25-28]. The patient described in this study was 76 years old. He had a large intrahepatic tumor measuring 17-18 cm. After surgical resection, he underwent chemotherapy. However, local recurrence occurred within a short time after surgery, and the disease progressed rapidly. The patient died within 3 mo after symptom onset. Among the 13 primary hepatic osteosarcoma cases in the literature, most patients died within 2 to 4 mo after initial diagnosis[2,7-15,17,18], but one article reported no tumors within 3 years of surgical resection and adjuvant chemotherapy[16]. At present, the treatment methods for hepatic osteosarcoma are similar to those used for other soft tissue sarcomas. Because this disease is rare, no evidence-based treatment plan has been established to date. Surgical resection combined with adjuvant chemoradiotherapy seems to be the best treatment option[24,25,28-30].

Hepatic osteosarcoma is a rare mesenchymal tumor with a short course and a high likelihood of metastasis and recurrence and is difficult to distinguish from other tumors by imaging. Its diagnosis still relies on pathological and immunochemical examinations. Compared with simple surgery or chemotherapy, the combination of surgical resection and chemotherapy may be the best treatment for the disease, which can slow disease progression, reduce the recurrence frequency, and prolong patient survival.

| 1. | Usui G, Hashimoto H, Kusakabe M, Shirota G, Sugiura Y, Fujita Y, Satou S, Harihara Y, Horiuchi H, Morikawa T. Intrahepatic Carcinosarcoma With Cholangiocarcinoma Elements and Prominent Bile Duct Spread. Int J Surg Pathol. 2019;27:900-906. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Zhang J, He X, Yu W, Ying F, Cai J, Deng S. Primary Exophytic Extraskeletal Osteosarcoma of the Liver: A Case Report and Literature Review. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2021;14:1009-1014. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bane BL, Evans HL, Ro JY, Carrasco CH, Grignon DJ, Benjamin RS, Ayala AG. Extraskeletal osteosarcoma. A clinicopathologic review of 26 cases. Cancer. 1990;65:2762-2770. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 4. | Wilson H. Extraskeletal ossifying tumors. Ann Surg. 1941;113:95-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 83] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Mc Auley G, Jagannathan J, O'Regan K, Krajewski KM, Hornick JL, Butrynski J, Ramaiya N. Extraskeletal osteosarcoma: spectrum of imaging findings. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;198:W31-W37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Lee S, Lee MR, Lee SJ, Ahn HK, Yi J, Yi SY, Seo SW, Sung KS, Park JO, Lee J. Extraosseous osteosarcoma: single institutional experience in Korea. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2010;6:126-129. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Maynard JH, Fone DJ. Haemochromatosis with osteogenic sarcoma in the liver. Med J Aust. 1969;2:1260-1263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sumiyoshi A, Niho Y. Primary osteogenic sarcoma of the liver--report of an autopsy case. Acta Pathol Jpn. 1971;21:305-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kitayama Y, Sugimura H, Arai T, Nagamatsu K, Kino I. Primary osteosarcoma arising from cirrhotic liver. Pathol Int. 1995;45:320-325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Liony C, Lemarchand P, Manchon ND, Bécret A, Bercoff E, Pellerin A, Tayot J, Bourreille J. [A case of primary osteosarcoma of the liver]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1990;14:1003-1006. [PubMed] |

| 11. | Govender D, Rughubar KN. Primary hepatic osteosarcoma: case report and literature review. Pathology. 1998;30:323-325. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | von Hochstetter AR, Hättenschwiler J, Vogt M. Primary osteosarcoma of the liver. Cancer. 1987;60:2312-2317. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 13. | Craig JR, Peters RL, Edmondson HA. Atlas of Tumor Pathology: Tumors of the Liver and Intrahepatic Bile Ducts. Second Series, Fascicle 26. Washington: Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, 1989: 223-255. |

| 14. | Krishnamurthy VN, Casillas VJ, Bejarano P, Saurez M, Franceschi D. Primary osteosarcoma of liver. Europ J Radiol Extra. 2004;50:31-36. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 15. | Park SH, Choi SB, Kim WB, Song TJ. Huge primary osteosarcoma of the liver presenting an aggressive recurrent pattern following surgical resection. J Dig Dis. 2009;10:231-235. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Nawabi A, Rath S, Nissen N, Forscher C, Colquhoun S, Lee J, Geller S, Wong A, Klein AS. Primary hepatic osteosarcoma. J Gastrointest Surg. 2009;13:1550-1553. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Tamang TG, Shuster M, Chandra AB. Primary Hepatic Osteosarcoma: A Rare Cause of Primary Liver Tumor. Clin Med Insights Case Rep. 2016;9:31-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Yu L, Yang SJ. Primary Osteosarcoma of the Liver: Case Report and Literature Review. Pathol Oncol Res. 2020;26:115-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lee JS, Fetsch JF, Wasdhal DA, Lee BP, Pritchard DJ, Nascimento AG. A review of 40 patients with extraskeletal osteosarcoma. Cancer. 1995;76:2253-2259. [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 20. | Murphey MD, Robbin MR, McRae GA, Flemming DJ, Temple HT, Kransdorf MJ. The many faces of osteosarcoma. Radiographics. 1997;17:1205-1231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 192] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Hamdan A, Toman J, Taylor S, Keller A. Nuclear imaging of an extraskeletal retroperitoneal osteosarcoma: respective contribution of 18FDG-PET and (99m)Tc oxidronate (2005:1b). Eur Radiol. 2005;15:840-844. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | WHO Classification of Tumours Editorial Board. WHO classification of tumours of soft tissue and bone. 5. Lyon: IARC Press, 2020. |

| 23. | Wang H, Miao R, Jacobson A, Harmon D, Choy E, Hornicek F, Raskin K, Chebib I, DeLaney TF, Chen YE. Extraskeletal osteosarcoma: A large series treated at a single institution. Rare Tumors. 2018;10:2036361317749651. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Miller BJ. CORR Insights(®): Should High-grade Extraosseous Osteosarcoma Be Treated With Multimodality Therapy Like Other Soft Tissue Sarcomas? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473:3612-3614. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Fan Z, Patel S, Lewis VO, Guadagnolo BA, Lin PP. Should High-grade Extraosseous Osteosarcoma Be Treated With Multimodality Therapy Like Other Soft Tissue Sarcomas? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473:3604-3611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Thampi S, Matthay KK, Boscardin WJ, Goldsby R, DuBois SG. Clinical Features and Outcomes Differ between Skeletal and Extraskeletal Osteosarcoma. Sarcoma. 2014;2014:902620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Pisters PW, Leung DH, Woodruff J, Shi W, Brennan MF. Analysis of prognostic factors in 1,041 patients with localized soft tissue sarcomas of the extremities. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:1679-1689. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 941] [Cited by in RCA: 932] [Article Influence: 31.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Federman N, Bernthal N, Eilber FC, Tap WD. The multidisciplinary management of osteosarcoma. Curr Treat Options Oncol. 2009;10:82-93. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 96] [Cited by in RCA: 106] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Berner K, Bjerkehagen B, Bruland ØS, Berner A. Extraskeletal osteosarcoma in Norway, between 1975 and 2009, and a brief review of the literature. Anticancer Res. 2015;35:2129-2140. [PubMed] |

| 30. | Nystrom LM, Reimer NB, Reith JD, Scarborough MT, Gibbs CP Jr. The Treatment and Outcomes of Extraskeletal Osteosarcoma: Institutional Experience and Review of The Literature. Iowa Orthop J. 2016;36:98-103. [PubMed] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Medicine, research and experimental

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C, C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Ariyachet C, Thailand; Dilek ON, Turkey; Garrido I, Portugal S-Editor: Wang JJ L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang JJ