Published online Feb 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i4.1394

Peer-review started: September 5, 2021

First decision: December 1, 2021

Revised: December 8, 2021

Accepted: December 23, 2021

Article in press: December 23, 2021

Published online: February 6, 2022

Processing time: 140 Days and 23.3 Hours

Although external penetrating laryngeal trauma is rare in the clinic, such cases often result in a high mortality rate. The early recognition of injury, protection of the airway, one-stage laryngeal reconstruction with miniplates and interdisciplinary cooperation are important in the treatment of such patients.

A 58-year-old male worker sustained a penetrating injury in the left neck. After computed tomography scanning at a local hospital, he was transferred to our hospital, where he underwent tracheotomy, neck exploration, extraction of the foreign object, debridement and repair of the thyroid cartilage using titanium miniplates. An endo laryngeal stent was inserted, which was removed 12 days later. The patient recovered well and his voice rapidly improved after surgery.

Penetrating laryngeal trauma is uncommon. We successfully treated a patient with early laryngeal reconstruction and management by interdisciplinary cooperation.

Core Tip: External penetrating laryngeal trauma is rare, and is associated with a high mortality rate. We report a 58-year-old male worker with a penetrating injury to the left neck caused by a metal fragment. The patient underwent tracheotomy, neck exploration, extraction of the neck foreign body, debridement and repair of the thyroid cartilage with titanium miniplates and endolaryngeal stenting. The patient recovered well and his voice rapidly improved. The good recovery of this patient highlights the importance of early laryngeal reconstruction and management by interdisciplinary cooperation.

- Citation: Qiu ZH, Zeng J, Zuo Q, Liu ZQ. External penetrating laryngeal trauma caused by a metal fragment: A Case Report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(4): 1394-1400

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i4/1394.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i4.1394

External penetrating laryngeal trauma is rare, but is a potentially life-threatening injury. It is mostly caused by sharp objects or great destructive force, similar to a gunshot wound and explosion injury[1-3]. Damage to the larynx may result in severe consequences, such as massive hemorrhage, cartilage fracture and airway collapse[4,5]. It presents with a spectrum of symptoms and signs that range from changes in voice quality to cardiopulmonary arrest due to airway obstruction[6]. Severe penetrating laryngeal trauma may be accompanied by injury to cervical great vessels, esophagus, trachea and chest[7]. Correct diagnosis and timely treatment are vital for improving patient survival and reducing the loss of organ function. When severe consequences occur, such as shock, bleeding and asphyxia, they should be treated immediately according to the general surgical principles for rescue, and tracheotomy should be performed[8-10]. In addition, early reconstruction of the larynx is important for vocal function reconstruction and recovery of patients with laryngeal cartilage fracture[7,8,11,12].

We here present a case of a 58-year-old male worker who suffered from an external penetrating laryngeal trauma and underwent timely management with one-stage laryngeal reconstruction, and achieved good functional results.

A 58-year-old Chinese male worker was walking in a construction site in Inner Mongolia when a metal rope suddenly broke. He was hit by a metal fragment due to the force of the metal rope. The fragment resulted in an injury to his left neck.

Due to this serious injury and the importance of the injured area, he was immediately transferred to a tertiary hospital in Beijing with a cervical collar for spinal immobilization.

The patient had no specific history of past illness.

The patient had no specific personal and family history.

Physical examination found an irregular and dirty wound of approximately 2 cm in his left neck.

The patient had no specific laboratory examination.

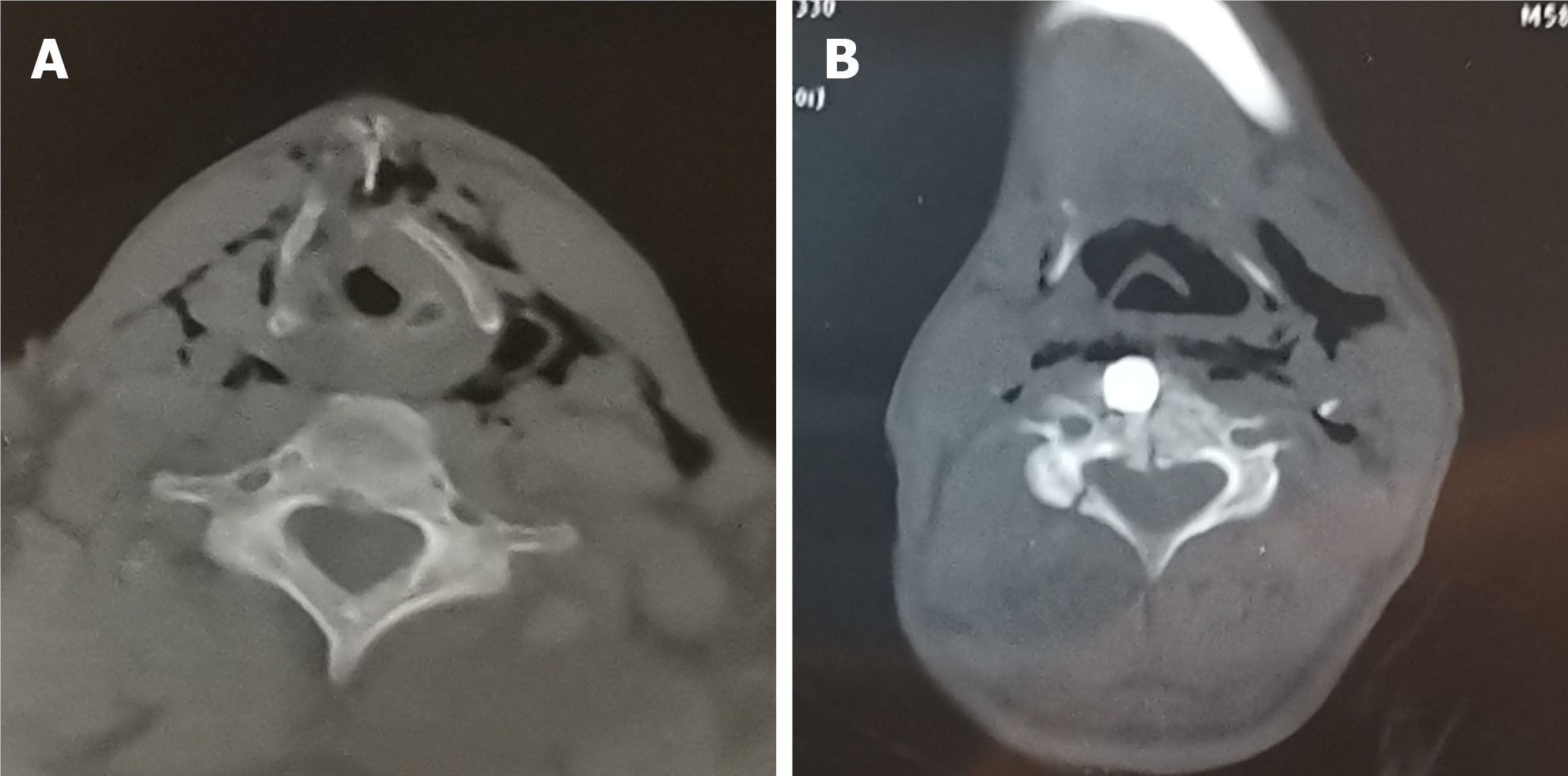

Upon admission, computed tomography (CT) was performed using a 64-row CT scanner (LightSpeed VCT, GE Medical Systems), with the following scanning parameters: 3.250 mm section thickness, 120 kVp, 498 mA, and 0.6 s rotation time. The patient underwent a standard diagnostic CT in the craniocaudal direction at a local hospital. CT scanning confirmed significant thyroid cartilage fracture, cervical emphysema, fracture of the C4 vertebra and right vertebral arch and a metal foreign object in front of the C4 vertebra (Figures 1A and 1B).

The final diagnosis was external penetrating laryngeal trauma of Schaefer-Fuhrman classification group 4 (Table 1).

| Group | Criteria |

| Group 1 | Minor endolaryngeal hematomas or lacerations; no detectable fracture |

| Group 2 | Edema, hematoma, minor mucosal disruption without exposed cartilage; nondisplaced fracture; varying degrees of airway compromise |

| Group 3 | Massive edema, large mucosal lacerations, exposed cartilage; displaced fracture(s); vocal cord immobility |

| Group 4 | Same as group 3 but more severe with: mucosal disruption; disruption of the anterior commissure; unstable fracture, two or more fracture line |

| Group 5 | Complete laryngotracheal separation |

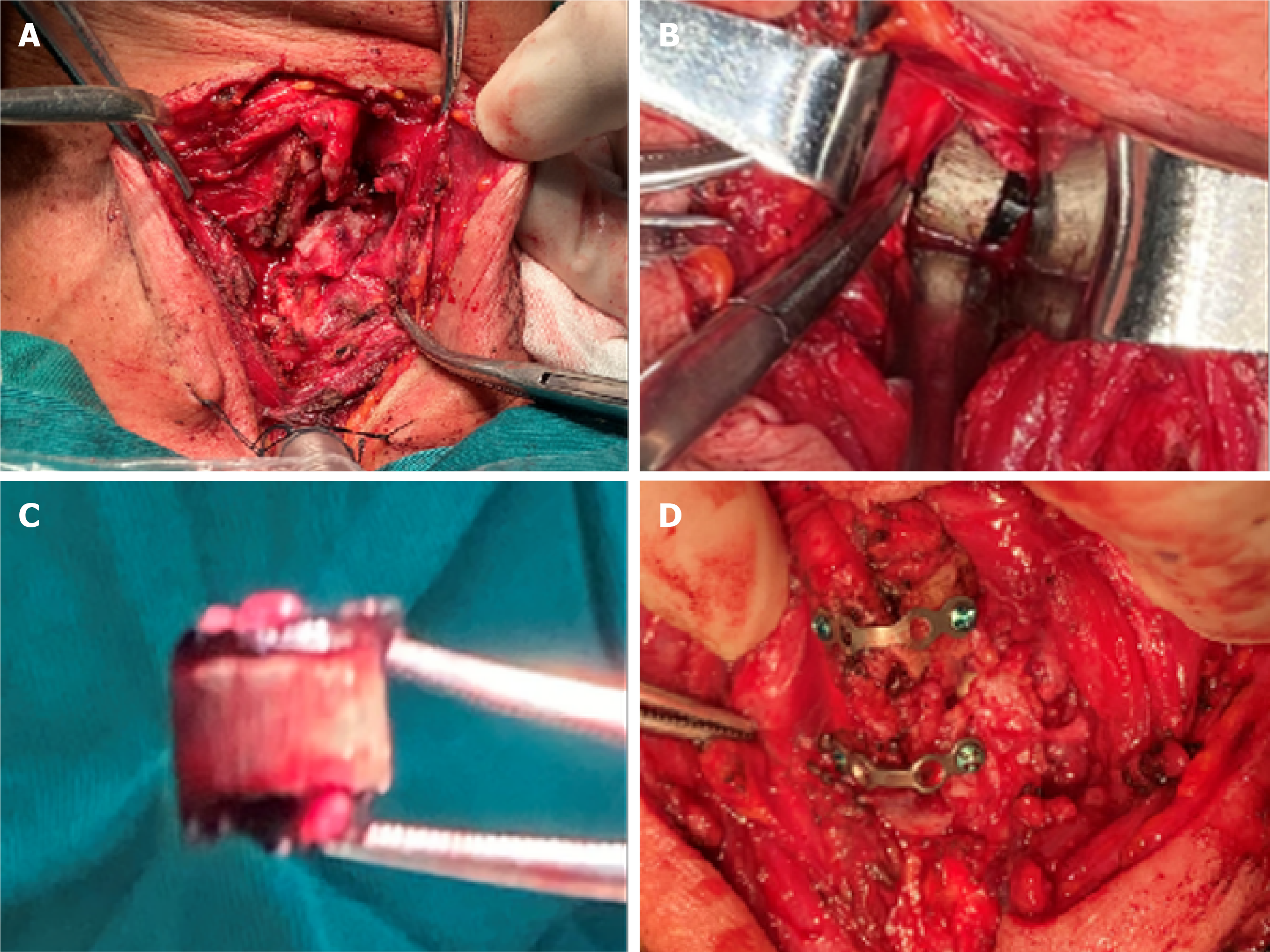

After an artificial airway was established by tracheotomy, the neck was explored. There was an irregular injury of approximately 2 cm in the left neck. The wound was dirty, and multiple fine black foreign objects were seen in the wound. The sinus tract formed by the trauma passed through the skin wound, the left thyroid cartilage and the pharynx to the front of the C4 vertebra. The left thyroid cartilage was broken into several fragments, while the right was largely intact. The structure of the left vocal cord, ventricular band and laryngeal ventricle was disordered, and the residual local mucosa was swollen and congested (Figure 2A). The anterior commissure, the right vocal cord, ventricular band and laryngeal ventricle were structurally clear, and the mucous membrane of the vocal cord and ventricular band was slightly swollen. A cylindrical metal foreign object of 1 cm × 1cm × 1 cm was seen which was partially lodged in the C4 vertebra (Figure 2B). The metal foreign object was removed by orthopedists (Figure 2C).

After adequate debridement, an endolaryngeal stent was inserted in order to support the laryngeal structure. The fragments of thyroid cartilage were repaired with two titanium miniplates (Figure 2D). A drainage tube was used to drain the hema

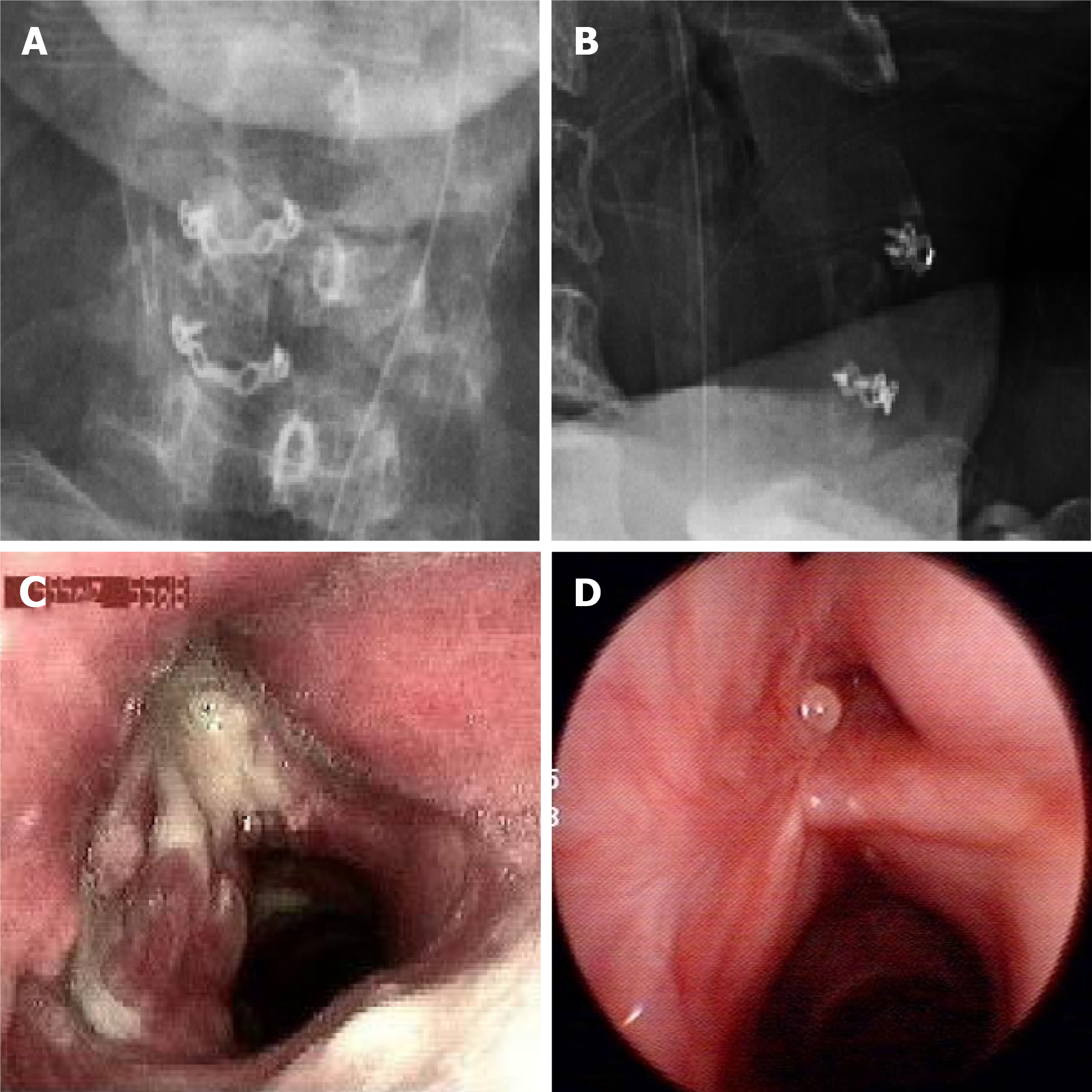

Post-operative radiography showed that the two plates were in a satisfactory position and no replacement was needed (Figure 3A and 3B). On the 14th day, fibrolaryngoscopy showed that the laryngeal structure was intact; there was hyperemia and swelling in the left vocal cord, some granulation tissues could be seen in the left vocal cord, ventricular band and laryngeal ventricle; the activity of the left vocal cord was poor, and both hyperemia and hypertrophy were observed in the right vocal cord (Figure 3C). Six months later, the patient returned for review, and dynamic laryn

Surgery for penetrating laryngeal trauma caused by a metal fragment is worth studying to avoid death among workers in the construction industry. Although external penetrating laryngeal trauma is uncommon, attention should be paid to such injuries. The clinical treatment of the patient in this report highlights several important aspects of the management of this injury. Rapid transportation of patients is essential, and the necessary examinations and treatment should be carried out as soon as possible.

Laryngeal trauma was classified into four groups by Schaefer[4]. In 1990, Fuhrman added a fifth group (Table 1)[13]. The case described here was classified into group 4.

The choice of examination is important for diagnosing injuries and optimal treatment planning. In this case, CT findings helped us make the primary diagnosis and determine the surgical plan. CT is more sensitive than flexible laryngoscopy for identifying laryngeal injury because it can show minimal cartilage fracture and other details[14,15]. In addition, distorted anatomy, bleeding and poor visualization may result in difficulties in laryngoscopy[7]. When plain CT cannot show radiological signs of potential vascular injuries, which may delay patients’ diagnoses, contrast-enhanced CT is more sensitive for vascular injuries[16]. In an emergency, contrast-enhanced CT is helpful in revealing details regarding the vessels and surrounding structures, such as angiorrhexis and hematoma[17,18]. In a retrospective study of 67 patients with penetrating neck injuries, combining clinical signs and radiological evidence improved the accuracy of exploration of injured vessels to 97.7%[19]. Therefore, contrast-enhanced CT is an essential examination for the diagnosis of injuries because of its high sensitivity in evaluating soft tissues, specifically vascular structures, in addition to fractures.

In patients with laryngeal trauma, the overriding priority is to maintain airway patency. Endotracheal intubation and tracheotomy have been recommended to establish a safe airway. However, intubating patients who have laryngeal injuries may be difficult or can fail, due to disordered anatomy, limited visualization and poor condition of the patients[8,9,10,20]. In our case, in order to avoid worsening the situation, we chose tracheotomy but not endotracheal intubation because of the severe laryngeal cartilage fracture with displacement of fragments and the unstable C4 vertebra fracture. Other reports have also shown that cricothyroidotomy may be a helpful temporary measure in emergency situations[20,21].

The optimal method and timing of surgery are controversial. A review of 77 patients revealed that expeditious repair of laryngeal injuries within 48 h could reduce the incidence of poor voice and/or airway outcomes[8]. In some retrospective studies, frequently, the airway repair was carried out within 8 h of the original injury[11,12]. Steven et al[7] suggested that patients with acute laryngeal trauma should undergo surgery within 24 h, or as soon as the patient can be brought to the operating room. Thanks to the short distance and rapid transportation, our patient received timely surgery within the window period.

In previous studies, several methods of repair and fixation were introduced. In a cadaveric study, miniplate fixation provided an easy procedure, tolerability, and superiority for thyroid cartilage fractures compared to wire fixation[22]. de Mello-Filho and Carrau reviewed 20 cases of laryngeal fractures repaired with miniplates, and most of them had good recovery of respiration, phonation and deglutition[23]. In the present case, the choice of repair was miniplate fixation, with good prognosis of various laryngeal functions.

Interdisciplinary cooperation is important because the force of high velocity damage usually causes multiple injuries, such as thyroid cartilage fracture and cervical injury. Emergent life-saving airway or hemodynamically stabilizing procedures have priority over spinal precautions[24]. Prehospital spinal immobilization is necessary in patients who have unstable fractures without an initial neurologic deficit[25]. In this case, good outcome was also attributed to spinal immobilization with a cervical collar and post-operative bed rest, which reduced the adverse effects of transportation and activity. Undoubtedly, a healthy physical condition before injury and high degree of compliance with treatment also played a role in achieving a good outcome.

External laryngeal trauma is rare but potentially fatal, which may be accompanied by injuries to other areas. Contrast-enhanced CT scanning is important for judging the severity of injuries. Maintaining airway patency is the key to patient management. Timely and appropriate treatment with interdisciplinary cooperation is essential for subsequent rehabilitation.

| 1. | Danic D, Prgomet D, Sekelj A, Jakovina K, Danic A. External laryngotracheal trauma. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2006;263:228-232. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Danić D, Prgomet D, Milicić D, Leović D, Puntarić D. War injuries to the head and neck. Mil Med. 1998;163:117-119. [PubMed] |

| 3. | Ucak M. Shrapnel Injuries on Regions of Head and Neck in Syrian War. J Craniofac Surg. 2020;31:1191-1195. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Schaefer SD. Primary management of laryngeal trauma. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1982;91:399-402. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 69] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Bell RB, Verschueren DS, Dierks EJ. Management of laryngeal trauma. Oral Maxillofac Surg Clin North Am. 2008;20:415-430. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Juutilainen M, Vintturi J, Robinson S, Bäck L, Lehtonen H, Mäkitie AA. Laryngeal fractures: clinical findings and considerations on suboptimal outcome. Acta Otolaryngol. 2008;128:213-218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Schaefer SD. Management of acute blunt and penetrating external laryngeal trauma. Laryngoscope. 2014;124:233-244. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 77] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Bent JP 3rd, Silver JR, Porubsky ES. Acute laryngeal trauma: a review of 77 patients. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1993;109:441-449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 93] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 9. | Jalisi S, Zoccoli M. Management of laryngeal fractures--a 10-year experience. J Voice. 2011;25:473-479. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Butler AP, Wood BP, O'Rourke AK, Porubsky ES. Acute external laryngeal trauma: experience with 112 patients. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2005;114:361-368. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Stassen NA, Hoth JJ, Scott MJ, Day CS, Lukan JK, Rodriguez JL, Richardson JD. Laryngotracheal injuries: does injury mechanism matter? Am Surg. 2004;70:522-525. [PubMed] |

| 12. | Konobu T, Nakamura T, Hata M, Ueyama T, Norimoto K, Fukushima H, Murao Y, Okuchi K. [Acute penetrating neck trauma presenting with laryngotracheal injury]. Kyobu Geka. 2005;58:475-480. [PubMed] |

| 13. | Fuhrman GM, Stieg FH 3rd, Buerk CA. Blunt laryngeal trauma: classification and management protocol. J Trauma. 1990;30:87-92. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Francis S, Gaspard DJ, Rogers N, Stain SC. Diagnosis and management of laryngotracheal trauma. J Natl Med Assoc. 2002;94:21-24. [PubMed] |

| 15. | Tsur N, Amitai N, Shoffel-Havakuk H, Abuhasira S, Hamzany Y. Forceful sneeze: An uncommon cause of laryngeal fracture. Radiol Case Rep. 2021;16:742-743. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Suzuki K, Shiono S, Hayasaka K, Endoh M. A surgical case of mediastinal hematoma caused by a minor traffic injury. J Cardiothorac Surg. 2020;15:12. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Lemke J, Schreiber MN, Henne-Bruns D, Cammerer G, Hillenbrand A. Thyroid gland hemorrhage after blunt neck trauma: case report and review of the literature. BMC Surg. 2017;17:115. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Arana-Garza S, Juarez-Parra M, Monterrubio-Rodríguez J, Cedillo-Alemán E, Orozco-Agüet D, Zamudio-Vázquez Z, Garza-Jasso T. Thyroid gland rupture after blunt neck trauma: A case report and review of the literature. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015;12:44-47. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Borsetto D, Fussey J, Mavuti J, Colley S, Pracy P. Penetrating neck trauma: radiological predictors of vascular injury. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2019;276:2541-2547. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Sharma N, De M, Martin T, Pracy P. Laryngeal reconstruction following shrapnel injury in a British soldier: case report. J Laryngol Otol. 2009;123:253-256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Mabry RL, Kharod CU, Bennett BL. Awake Cricothyrotomy: A Novel Approach to the Surgical Airway in the Tactical Setting. Wilderness Environ Med. 2017;28:S61-S68. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Lykins CL, Pinczower EF. The comparative strength of laryngeal fracture fixation. Am J Otolaryngol. 1998;19:158-162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 49] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | de Mello-Filho FV, Carrau RL. The management of laryngeal fractures using internal fixation. Laryngoscope. 2000;110:2143-2146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 36] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Medzon R, Rothenhaus T, Bono CM, Grindlinger G, Rathlev NK. Stability of cervical spine fractures after gunshot wounds to the head and neck. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30:2274-2279. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Schubl SD, Robitsek RJ, Sommerhalder C, Wilkins KJ, Klein TR, Trepeta S, Ho VP. Cervical spine immobilization may be of value following firearm injury to the head and neck. Am J Emerg Med. 2016;34:726-729. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open-Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Otorhinolaryngology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): B

Grade C (Good): 0

Grade D (Fair): 0

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Verde F S-Editor: Wang JL L-Editor: A P-Editor: Wang JL