Published online Nov 6, 2022. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v10.i31.11652

Peer-review started: July 31, 2022

First decision: September 5, 2022

Revised: September 15, 2022

Accepted: September 27, 2022

Article in press: September 27, 2022

Published online: November 6, 2022

Processing time: 88 Days and 2.5 Hours

Colonoscopy has become a routine physical examination as people’s health awareness has increased. Polyethylene glycol (PEG) is greatly used in bowel preparation before colonoscopy due to its price and safety advantages. Septic shock after colonoscopy with PEG preparation is extremely rare, with only very few cases in critically ill patients. Herein, we describe a case of septic shock in a healthy young adult immediately following colonoscopy with PEG preparation.

A 33-year-old young adult presented to our hospital for colonoscopy with PEG bowel preparation due to recurrent diarrhea for 7 years. The male's previous physical examination showed no abnormal indicators, and colonoscopy results were normal; however, he exhibited septic shock and markedly elevated white blood cell, C-reactive protein, and procalcitonin levels on the second day after colonoscopy. Immediate resuscitation and intensive care with appropriate antibiotics improved his condition. However, the blood and stool cultures did not detect the pathogen

Septic shock after colonoscopy is rare, especially in young adults. The authors considered the possibility of opportunistic infections after PEG bowel preparation, and clinicians should monitor patients for the possibility of such complications

Core Tip: We describe a case of septic shock with markedly elevated white blood cell, C-reactive protein, and procalcitonin levels in a 33-year-old healthy young adult immediately following colonoscopy with polyethylene glycol (PEG) preparation. Analysis of the cases indexed in PubMed in addition to this case report indicates that septic shock after colonoscopy is rare, especially in healthy young adults. The authors considered the possibility of opportunistic infections after PEG bowel preparation, and clinicians should monitor patients for the possibility of such complications. Aggressive treatment can rapidly improve patient symptoms

- Citation: Song JJ, Wu CJ, Dong YY, Ma C, Gu Q. Unexplained septic shock after colonoscopy with polyethylene glycol preparation in a young adult: A case report. World J Clin Cases 2022; 10(31): 11652-11657

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2307-8960/full/v10/i31/11652.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.12998/wjcc.v10.i31.11652

Due to the price and safety advantages, Polyethylene glycol (PEG) is greatly used as a bowel preparation for colonoscopy[1]. The PubMed and EMBASE databases were searched through May 2022 using the following terms and operators: [(Polyethylene glycol) OR (PEG)] AND (infection). Only 3 cases of bacteremia after ingestion of PEG have been reported, mainly due to bacterial translocation, and all patients had a history of chronic underlying diseases[2-4]. Herein, a case of septic shock after colonoscopy with PEG preparation in a healthy adult male with no underlying medical history was described.

A 33-year-old man presented to the emergency department with diarrhea and fever for 1 d.

The patient developed diarrhea without hematochezia more than 10 times. In addition, he vomited his stomach contents twice without hematemesis, which was accompanied by fever (38.2 °C).

The patient had had repeated belching, bloating and diarrhea for 7 years, but the examinations that were performed, including blood tests, abdominal ultrasonography, and computed tomography (CT) examinations, showed no abnormalities. Therefore, it was recommended that the patient undergo gastrointestinal endoscopy after he presented to the outpatient department of gastroenterology in our hospital. According to our center's bowel preparation requirement, the patient was given 2 boxes of regular PEG dissolved in 4 Liters of water for bowel preparation. After adequate bowel preparation, the patient underwent gastrointestinal endoscopy, including both gastroscopy and, on December 30, 2021. We performed the gastroscopy first, followed by the colonoscopy. The results of the gastroscopy showed hiatal hernia, chronic nonatrophic gastritis with erosions, and multiple polyps in the fundus (removed by biopsy forceps). There were 2 gastric polyps (0.2-0.3 cm) in total, all of which were Yamada type II. We used biopsy forceps for cold biopsy, and the pathological diagnosis was fundic gland polyps. The colonoscopy showed no abnormal findings (no congestion, injury, diverticulum, or mass in the colonic mucosa). After the examination, the patient had no complaints of discomfort and left the hospital after receiving the examination results.

The patient denied any family history of digestive tract disease.

On physical examination, the vital signs were as follows: Body temperature, 39 °C; blood pressure, 114/65 mmHg; heart rate, 115 beats per min; and respiratory rate, 18 breaths per min. No positive signs were observed in the abdomen.

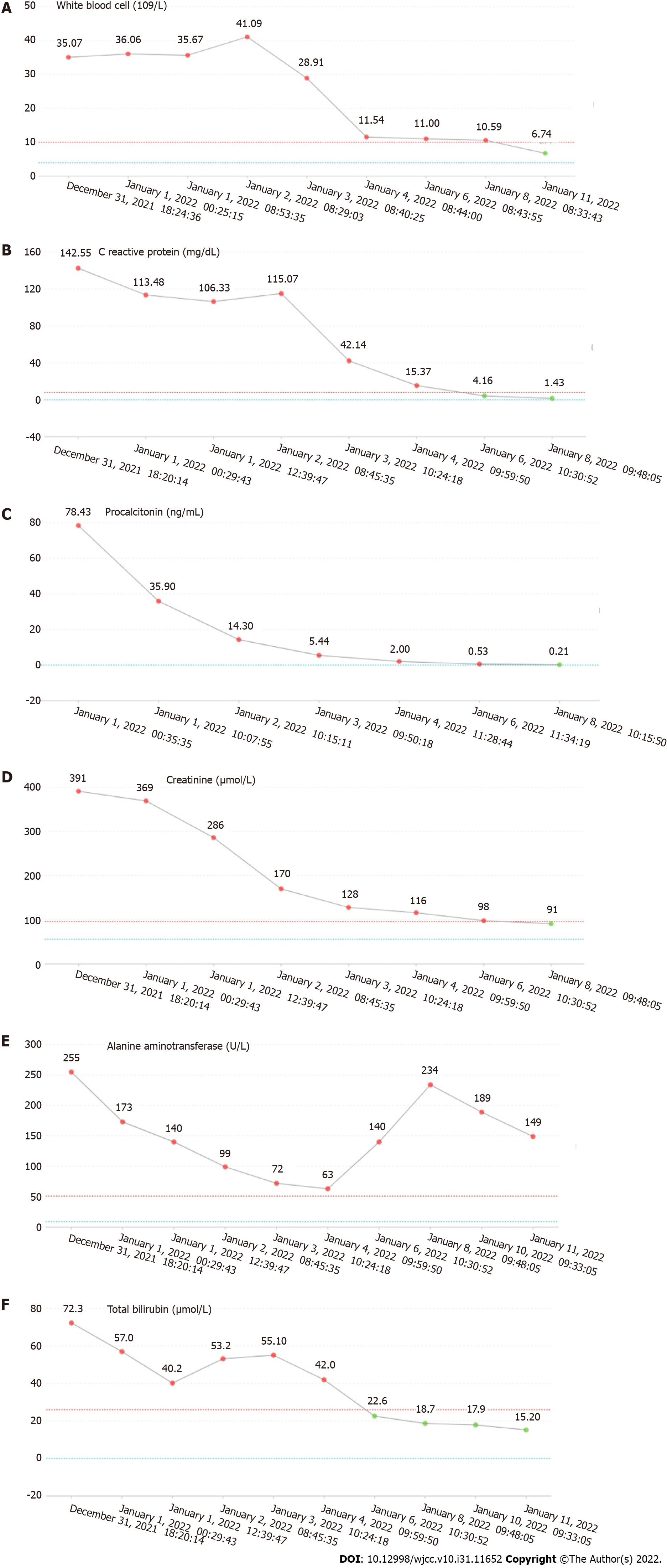

The laboratory tests returned the following results: Plasma D-dimer, 21800.00 μg/L; brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), 7330.00 pg/mL; white blood cells, 35.07 × 109/L; C-reactive protein, 142.55 mg/dL; procalcitonin, 78.43 ng/mL; lactic acid, 3.3 mmol/L; creatinine, 391 μmol/L; alanine aminotransferase, 255 U/L; aspartate aminotransferase, 204 U/L; total bile, 72.3 μmol/L; direct bile, 41.1 μmol/L; and γ-glutamyltransferase, 219 U/L. The changes in laboratory examination results are shown in Figure 1.

The abdominal CT examination showed no abnormalities, and lung CT showed a small amount of inflammation in the lower lobe of the left lung.

The patient was given symptomatic and supportive treatment, including stomach protection (omeprazole, 40 mg, iv, BID), liver protection (compound glycyrrhizin injection, 20 mL, ivgtt, QD; ademetionine 1,4-butanedisulfonate for injection, 0.5 g, ivgtt, QD), and anti-infection (levofloxacin, 0.5 g, ivgtt, QD), but the patient’s condition did not improve. We found that the patient had a progressively elevated body temperature, persistently high leukocyte index, and metabolic acidosis. The patient’s oxygenation was maintained at 100% under nasal cannula oxygen inhalation, but the patient’s respiratory rate increased to a maximum of 25 breaths per min, heart rate was 124 beats per min, blood pressure was 89/60 mmHg, and a clear systemic inflammatory response was observed. At that time, the possibility of septic shock was considered. In addition, the patient developed acute renal insufficiency and hepatic insufficiency, and the patient was considered to be complicated by multiple organ failure. Therefore, he was immediately transferred to the intensive care unit (ICU).

After being admitted to the ICU, the patient reached the highest body temperature at 40.1 °C. During this period, the treatment plan was mainly focused on preventing infection and maintaining circulatory stability. After 2 d of anti-infection treatment with piperacillin sodium and tazobactam sodium for injection (4.5 g, ivgtt, Q8H), the patient's body temperature dropped to 36.8 °C, lactate level was 1.0, and white blood cell count dropped to 11.54 × 109/L. Once the patient showed improvement, he was transferred to the general ward. After 2 d of observation and treatment, the abnormal indicators were significantly improved, and the patient was discharged. Unfortunately, no pathogenic bacteria were detected in blood culture or stool culture during the patient’s treatment process.

Severe infection, septic shock, and multiple organ failure.

The treatment plan was mainly focused on preventing infection and maintaining circulatory stability. The final recovery of the patient showed that this treatment plan was effective.

At 6 mo postoperatively, the patient was in good condition.

The course of this patient indicated an important and rare clinical implication that PEG may cause septic shock in normal adults after bowel preparation. The three previously reported cases of septic shock occurred in patients with a history of underlying diseases, including ICU admission, ulcerative colitis, and functional constipation. Two patients' blood cultures detected Escherichia coli[2,3], and the other patient’s blood cultures Citrobacter. braakii[4].

The patient had a history of recurrent diarrhea for 7 years, which may indicate intestinal flora imbalance. However, researchers did not have enough evidence to diagnose an imbalance because the patient had not undergone genetic sequencing of fecal flora, and the patient's symptoms did not improve after taking probiotics. Further discussion of the possible route of infection in this case showed that the time series of the patient's rapid deterioration following PEG ingestion suggested PEG-induced septic shock. Urinalysis, stool culture, and blood culture were all negative, so the source of infection could not be determined. However, we performed anti-infective treatment before blood and stool cultures were taken, which may have affected the reliability of the culture results. After a comprehensive analysis, it was believed that bacterial translocation may be an important factor leading to septic shock when combined with bowel preparation and gastrointestinal endoscopy. A commonly proposed mechanism for bacterial translocation is physical damage to intestinal mucosal barrier function, resulting in increased permeability[5-7]. A previous study showed that starvation for only 24 h can lead to marked microbial changes in cecal contents and increase bacterial adhesion to cecal epithelial cells, suggesting that bacterial overgrowth is an important factor associated with bacterial translocation[8]. Oral administration of PEG to the patient may lead to the destruction of the luminal factor defense function of the gastrointestinal tract, including mucus, gastric acid, pancreatic enzymes, and bile, resulting in intestinal mucosal damage[9]. Previous studies have also shown that PEG may cause histopathological damage to the colon wall, although the damage is likely minor[10].

In addition to infection with an intestinal point of origin, we also considered whether other factors induced severe infection. First, we considered a potential diverticulum perforation by colonoscopy or by polyp cold biopsy; second, we considered a pulmonary infection caused by reflux aspiration during examination under anesthesia; and third, we considered an unclean diet resulting in acute gas

To our knowledge, this is the first report of septic shock in a young adult following PEG ingestion in preparation for colonoscopy. However, there are still deficiencies in this case, including an inability to identify the pathogenic bacteria and a lack of direct evidence to confirm bacterial translocation. However, this case recommends caution for clinicians, who should be aware that PEG can lead to serious complications after bowel preparation. Because the patient had no underlying diseases and no warning factors, this case report suggests that if septic shock occurs after gastrointestinal endoscopy, PEG may be the culprit after excluding common factors.

Septic shock after colonoscopy is rare, especially in young adults. The authors considered the possibility of opportunistic infections after PEG bowel preparation, and clinicians should monitor patients for the possibility of such complications.

Provenance and peer review: Unsolicited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Gastroenterology and hepatology

Country/Territory of origin: China

Peer-review report’s scientific quality classification

Grade A (Excellent): 0

Grade B (Very good): 0

Grade C (Good): C

Grade D (Fair): D

Grade E (Poor): 0

P-Reviewer: Iglesias J, United States; Moldovan CA, Romania S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Liu JH

| 1. | Hassan C, Bretthauer M, Kaminski MF, Polkowski M, Rembacken B, Saunders B, Benamouzig R, Holme O, Green S, Kuiper T, Marmo R, Omar M, Petruzziello L, Spada C, Zullo A, Dumonceau JM; European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy. Bowel preparation for colonoscopy: European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) guideline. Endoscopy. 2013;45:142-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 290] [Cited by in RCA: 315] [Article Influence: 24.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Darrow CJ, Devito JF. An occurrence of sepsis during inpatient fecal disimpaction. Pediatrics. 2014;133:e235-e239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Fukutomi Y, Tajika M, Yamazaki K, Iwata K, Shimizu S, Yasuda S, Ohnishi H, Shimizu M, Sasaki E, Kato T. A case of ulcerative colitis associated with sepsis and intra vertebral canal abscess induced by oral administration of polyethylene glycol electrolyte lavage solution. Gastroenterological Endoscopy. 2004;46:1181-1185. |

| 4. | Yumoto T, Kono Y, Kawano S, Kamoi C, Iida A, Nose M, Sato K, Ugawa T, Okada H, Ujike Y, Nakao A. Citrobacter braakii bacteremia-induced septic shock after colonoscopy preparation with polyethylene glycol in a critically ill patient: a case report. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2017;16:22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Chakravartty S, Chang A, Nunoo-Mensah J. A systematic review of stercoral perforation. Colorectal Dis. 2013;15:930-935. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 43] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Giannelli V, Di Gregorio V, Iebba V, Giusto M, Schippa S, Merli M, Thalheimer U. Microbiota and the gut-liver axis: bacterial translocation, inflammation and infection in cirrhosis. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20:16795-16810. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in CrossRef: 156] [Cited by in RCA: 176] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 7. | Steinberg SM. Bacterial translocation: what it is and what it is not. Am J Surg. 2003;186:301-305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Demirogullari B, Poyraz A, Cirak MY, Sonmez K, Ozen IO, Kulah C, Karabulut B, Basaklar AC, Kale N. Effects of hyperosmolar agents--lactulose, lactitol, sodium phosphate and polyethylene glycol--on cecal coliform bacteria during traditional bowel cleansing: an experimental study in rats. Eur Surg Res. 2004;36:159-164. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wiest R, Rath HC. Gastrointestinal disorders of the critically ill. Bacterial translocation in the gut. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2003;17:397-425. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 144] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Gremse DA, Hixon J, Crutchfield A. Comparison of polyethylene glycol 3350 and lactulose for treatment of chronic constipation in children. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2002;41:225-229. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 87] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |