Published online Mar 20, 2026. doi: 10.5662/wjm.v16.i1.109733

Revised: June 23, 2025

Accepted: September 26, 2025

Published online: March 20, 2026

Processing time: 266 Days and 22 Hours

Sepsis causes significant mortality in patients. Typically, the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score is used; however, recent studies have demon

To assess the prognostic value of integrating ferritin and NLR with SOFA in predicting mortality in critically ill patients with sepsis.

Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care database-IV database was used to conduct this retrospective cohort study. Patients were divided into quartiles based on values of serum ferritin and NLR. Cox proportional hazards regression asse

Patients in the ferritin Q1 quartile (lowest ferritin quartile) had 30% lower adjusted mortality risk (hazard ratio [HR]: 0.71, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.57-0.9; P = 0.005) compared to Q3 (highest ferritin quartile). Similarly, NLR Q1 (lowest NLR quartile) had 27% lower adjusted mortality risk (HR: 0.73, 95%CI: 0.59-0.91; P = 0.006). Moreover, patients with both serum ferritin and NLR in the Q1 (lowest) quartile had the lowest risk of mortality (HR: 0.56, 95%CI: 0.42-0.74; P < 0.001). With biomarker integration, the AUROC improved from 0.602 (95%CI: 0.574-0.630) for SOFA alone to 0.656 (0.629-0.683; P < 0.001), primarily driven by ferritin. NRI demonstrated a modest but significant improvement in reclassification. Old age was also found to be associated with a higher risk of mortality.

Lower ferritin and NLR are associated with reduced 30-day mortality, with ferritin markedly improving SOFA-based prediction and NLR offering minimal added benefit. Accessible biomarkers enhance early risk assessment in low-resource intensive care units.

Core Tip: This study evaluated the added prognostic value of combining serum ferritin and neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio with Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) in predicting 30-day mortality among critically ill adult patients with sepsis. Using data from the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care database, the integration of these inflammatory biomarkers with SOFA improved model discrimination and reclassification, supporting their potential role in enhancing early risk stratification in sepsis.

- Citation: Patel N, Patel V, Murugan Y, Patel K, Varma V, Surani S. Integrating serum ferritin and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio with Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score improves mortality prediction in sepsis. World J Methodol 2026; 16(1): 109733

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2222-0682/full/v16/i1/109733.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5662/wjm.v16.i1.109733

Sepsis is a life-threatening condition characterized by organ dysfunction as a result of the dysregulated host response to infection[1]. Septic shock is a more severe form involving circulatory and metabolic abnormalities that significantly increases mortality risk[1]. Sepsis is manageable, but the prompt administration of targeted therapies highly influences clinical outcomes[2,3]. The World Health Organization has stressed the global burden of sepsis, emphasizing the importance of improving health information systems and high-quality care to alleviate its impact[4].

The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation 2020 report estimates that approximately 48.9 million global sepsis cases and 11 million sepsis-related deaths were reported in 2017, highlighting the major impact of sepsis on global mo

The pathogenesis of sepsis includes activating immune cells like monocytes and neutrophils via the pathogen recognition receptors. This triggers the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines like interleukins (IL-1, IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor alpha, causing endothelial damage, increased capillary permeability, and microvascular thrombosis[6]. At the same time, an imbalanced immune state is created by the activation of anti-inflammatory responses, leading to immunosuppression and increased susceptibility to secondary infections[7]. Septic shock is the most severe form of sepsis, characterized by significant circulatory and metabolic abnormalities, including vasoplegia, impaired utilization of oxygen, and mitochondrial dysfunction, causing persistent hypotension and multiple organ failures despite adequate fluid resuscitation[8]. This combination of immune dysregulation and vascular pathology highlights the early recognition in patients with sepsis for improved outcomes.

While the Surviving Sepsis Campaign continues to refine its guidelines, the complex and often unpredictable clinical course of sepsis remains a major concern[8]. Early detection is important in improving outcomes, highlighting the need for effective and accessible biomarkers, not only in early diagnosis and prognostication but also to enable timely access to emerging adjunctive or experimental therapies. Adjunctive immunomodulatory treatments such as immunoglobulin M-enriched intravenous immunoglobulins and blood purification techniques are being explored, although supporting evidence for these interventions is still developing[9,10].

Over recent years, biomarkers such as procalcitonin and C-reactive protein have been extensively studied to assess their potential roles in sepsis diagnosis, prognosis, and guiding treatment decisions[7]. Ferritin, an iron-storage protein along with an acute phase reactant, plays an important role in the immune response of the host against infection[11,12]. Serum ferritin levels are elevated during systemic inflammation due to the release of inflammatory cytokines[13].

Another biomarker that has also gained attention for its association with inflammation is the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR). It is increasingly being recognized as an indicator of the severity of the disease, with elevated NLR levels linked to poor outcomes in patients with sepsis[14-16].

Considering the individual roles of serum ferritin and NLR in sepsis, this study explored their combined prognostic significance in critically ill adult patients with sepsis. No study has specifically evaluated the combined role of serum ferritin and NLR with Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) in sepsis prognosis, making this study the first to explore such a model. This study proposes a novel model using the Medical Information Mart for Intensive Care IV (MIMIC-IV) database, which offers a cost-effective and practical solution to improving early risk stratification and guiding sepsis management.

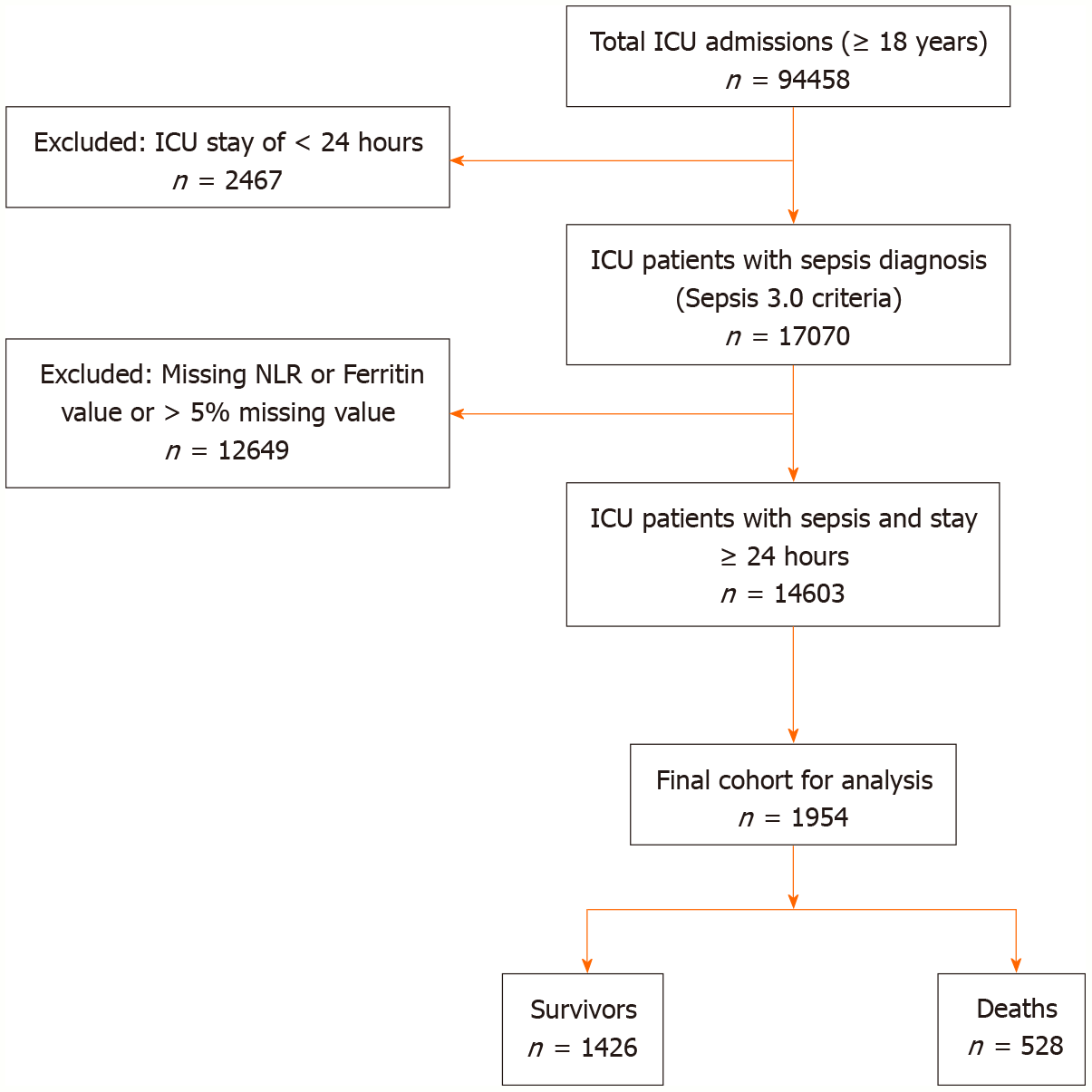

This retrospective study used data from 2008-2022 available in MIMIC-IV v3.1 from Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Centre (Boston, MA, United States)[17-19]. Adult patients (≥ 18 years) who were admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) meeting Sepsis-3 criteria were included. Figure 1 shows the flow chart of patient inclusion and exclusion as per the Strengthening the Report of Observational Studies in Epidemiology recommendations.

Inclusion criteria: Adult patients diagnosed with sepsis according to Sepsis 3.0 criteria[1].

Exclusion criteria: (1) Age < 18 years; (2) ICU admission for less than 24 hours; (3) Have missing ferritin or NLR or SOFA score components; or (4) > 5% missing data for all variables.

Data were collected using a structured query language from the MIMIC-IV database. Key variables like age, sex, Charlson comorbidity index (CCI), serum ferritin, absolute neutrophil count, absolute lymphocyte count, hospital admission time, ICU admission time, ICU discharge time, hospital discharge status, hospital discharge time, and SOFA score components, namely, mean arterial pressure, vasopressors, serum creatinine, urine output, platelets count, partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood (PaO2), fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2), invasive or non-invasive ventilation, total bilirubin, and Glasgow Coma Scale score were extracted from the database.

SOFA score: The SOFA score was calculated based on the worst values recorded within the first 24 hours of ICU ad

| Organ system | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

| Respiratory (mmHg) | PaO2/FiO2 ≥ 400 | PaO2/FiO2 < 400 | PaO2/FiO2 < 300 | PaO2/FiO2 < 200 and ventilated | PaO2/FiO2 < 100 and ventilated |

| Coagulation (platelets 103/μL) | Platelets ≥ 150 | Platelets < 150 | Platelets < 100 | Platelets < 50 | Platelets < 20 |

| Liver (mg/dL) | Bilirubin < 1.2 | Bilirubin 1.2-1.9 | Bilirubin 2.0-5.9 | Bilirubin 6.0-11.9 | Bilirubin ≥ 12.0 |

| Cardiovascular | MAP ≥ 70 mmHg | MAP < 70 mmHg | Dopamine < 5 or dobutamine (any dose) | Dopamine 51-15 or epinephrine ≤ 0.1 or norepinephrine ≤ 0.1 | Dopamine > 15 or epinephrine > 0.1 or norepinephrine > 0.1 |

| CNS GCS Score | 15 | 13-14 | 10-12 | 6-9 | < 6 |

| Renal | Creatinine < 1.2 mg/dL | Creatinine 12-1.9 mg/dL | Creatinine 20-3.4 mg/dL | Creatinine 35-4.9 mg/dL; urine output < 500 mL/day | Creatinine > 5 mg/dL; urine output < 200 mL/day |

CCI: The CCI was calculated using the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems 10th Revision codes within the MIMIC-IV database using the algorithm developed by Quan et al[20] This index assigns weightage to various comorbid conditions, and a final score is calculated. The final score was used as a covariate.

NLR: NLR was calculated as follows. The blood sample values were taken within 24 hours of ICU admission. It was computed as the absolute neutrophil count divided by the absolute lymphocyte count. This marker has gained attention as a cost-effective and readily available indicator of systemic inflammation in critically ill patients.

Descriptive statistics were calculated for all variables, with continuous data presented as the means ± standard deviations. Categorical data are summarized as frequencies and percentages.

Comparisons between groups were conducted using the independent t-test for normally distributed continuous variables and Mann-Whitney U test for non-formally distributed tests. χ2 or Fisher’s exact tests were used for categorical variables.

Survival outcomes were analyzed using Kaplan-Meier methodology, with differences between groups assessed via log-rank tests. Survival curves were presented using KMunicate-style plots to enhance interpretability, with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) calculated for each group. Cox proportional hazards models were constructed to evaluate the associations between key biomarkers (ferritin and NLR) and 30-day mortality. Both unadjusted and adjusted models were developed, with the latter accounting for potential confounders including age, sex, and CCI. The proportional hazards assumptions were tested using Schoenfeld residuals. Biomarker values were categorized into quartiles to facilitate clinical interpretation, with highest quartile serving as reference group. A combined analysis examining the synergistic effect of both biomarkers was also performed. Results are presented as hazards ratio (HRs) with 95%CIs. For all analyses, two-sided P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. No imputation methods were employed for missing data; only patients with complete data for variables were included in analyses.

For model discrimination, we calculated area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) for each model and compared AUROCs via DeLong tests using SOFA alone models as reference. Internal validation of predictive models was performed by bootstrap resampling with 1000 iterations to estimate and correct for optimism. Calibration was assessed with calibration plots (bootstrapped), and net reclassification improvement (NRI) was computed to quantify change in risk classification when adding biomarkers to the reference model.

Table 2 comprehensively presents the demographic, clinical, and laboratory characteristics of the study cohort (n = 1954), stratified by 30-day survival status. Significant differences between survivors (n = 1426) and deaths (n = 528) were observed across multiple parameters. Patients who died were significantly older (67.7 years vs 59.4 years; P < 0.001) and had higher CCI scores (2.8 vs 2.0; P < 0.001). The prevalence of comorbidities including hypertension, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney disease, chronic liver disease, and malignancy was significantly higher among patients who died.

| Characteristic | All patients (n = 1954) | Survivors (n = 1426) | Deaths (n = 528) | P value |

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, years (mean ± SD) | 61.6 ± 15.3 | 59.4 ± 15.2 | 67.7 ± 13.7 | < 0.001 |

| Sex | 0.364 | |||

| Male | 1082 (55.4) | 778 (54.6) | 304 (57.6) | |

| Female | 872 (44.6) | 648 (45.4) | 224 (42.4) | |

| BMI, kg/m2 (mean ± SD) | 28.3 ± 7.9 | 28.5 ± 8.0 | 27.8 ± 7.7 | 0.107 |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| Charlson comorbidity index (mean ± SD) | 2.2 ± 2.2 | 2.0 ± 2.1 | 2.8 ± 2.4 | < 0.001 |

| Hypertension | 823 (42.1) | 566 (39.7) | 257 (48.7) | < 0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 517 (26.5) | 362 (25.4) | 155 (29.4) | 0.079 |

| COPD | 304 (15.6) | 198 (13.9) | 106 (20.1) | 0.001 |

| Chronic kidney disease | 386 (19.8) | 247 (17.3) | 139 (26.3) | < 0.001 |

| Chronic liver disease | 215 (11.0) | 137 (9.6) | 78 (14.8) | 0.001 |

| Malignancy | 293 (15.0) | 177 (12.4) | 116 (22.0) | < 0.001 |

| Source of infection1 | 0.019 | |||

| a: Pulmonary | 809 (41.4) | 565 (39.6) | 244 (46.2) | |

| b: Urinary | 421 (21.5) | 333 (23.4) | 88 (16.7) | |

| c: Abdominal | 389 (19.9) | 288 (20.2) | 101 (19.1) | |

| d: Bloodstream | 215 (11.0) | 147 (10.3) | 68 (12.9) | |

| e: Other/unknown | 120 (6.1) | 93 (6.5) | 27 (5.1) | |

| Clinical parameters at admission | ||||

| Systolic BP, mmHg (mean ± SD) | 118.7 ± 24.5 | 121.8 ± 22.9 | 110.4 ± 26.7 | < 0.001 |

| MAP, mmHg (mean ± SD) | 78.5 ± 16.0 | 80.6 ± 14.9 | 73.0 ± 17.2 | < 0.001 |

| Heart rate, bpm (mean ± SD) | 101.3 ± 21.8 | 100.1 ± 20.9 | 104.5 ± 23.7 | < 0.001 |

| Respiratory rate, breaths/min (mean ± SD) | 22.8 ± 6.2 | 22.0 ± 5.8 | 24.9 ± 6.7 | < 0.001 |

| Temperature, °C (mean ± SD) | 37.3 ± 1.1 | 37.4 ± 1.0 | 37.0 ± 1.2 | < 0.001 |

| SpO2, % (mean ± SD) | 94.8 ± 4.7 | 95.4 ± 4.2 | 93.2 ± 5.5 | < 0.001 |

| Laboratory values | ||||

| Ferritin (mean ± SD) (ng/mL) | 1480.9 ± 2912.1 | 1196.4 ± 2423.8 | 2223.5 ± 3766.6 | < 0.001 |

| NLR (mean ± SD) | 31.6 ± 95.3 | 24.7 ± 85.6 | 50.1 ± 114.4 | < 0.001 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL (mean ± SD) | 11.2 ± 2.3 | 11.4 ± 2.2 | 10.6 ± 2.3 | < 0.001 |

| WBC count, × 10³/μL (mean ± SD) | 15.8 ± 11.2 | 15.2 ± 10.6 | 17.3 ± 12.4 | < 0.001 |

| Platelet count, × 10³/μL (mean ± SD) | 217.3 ± 119.0 | 228.9 ± 119.8 | 186.8 ± 111.2 | < 0.001 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL (mean ± SD) | 1.7 ± 1.5 | 1.5 ± 1.3 | 2.1 ± 1.8 | < 0.001 |

| Total bilirubin, mg/dL (mean ± SD) | 1.4 ± 2.5 | 1.2 ± 2.1 | 2.0 ± 3.2 | < 0.001 |

| Lactate, mmol/L (mean ± SD) | 2.9 ± 2.4 | 2.4 ± 1.8 | 4.1 ± 3.2 | < 0.001 |

| Interventions | ||||

| Invasive ventilation | 782 (40.0) | 483 (33.9) | 299 (56.6) | < 0.001 |

| Vasopressor use | 897 (45.9) | 560 (39.3) | 337 (63.8) | < 0.001 |

| Dialysis | 326 (16.7) | 198 (13.9) | 128 (24.2) | < 0.001 |

| Outcomes | ||||

| ICU stay duration, days (mean ± SD) | 6.3 ± 7.8 | 5.9 ± 7.2 | 7.4 ± 9.1 | 0.001 |

| Hospital stay duration, days (mean ± SD) | 14.2 ± 13.4 | 15.8 ± 13.7 | 10.1 ± 11.5 | < 0.001 |

Notably, the source of infection differed between groups (P = 0.019), with pulmonary infections more common among person who died (46.2% vs 39.6%) and urinary infections more frequent in survivors (23.4% vs 16.7%). Clinical parameters at admission revealed that patients who died presented with worse hemodynamic status, including lower systolic blood pressure (110.4 mmHg vs 121.8 mmHg; P < 0.001) and mean arterial pressure (73.0 mmHg vs 80.6 mmHg; P < 0.001), along with higher heart and respiratory rates.

Laboratory values showed striking differences in the biomarkers of interest. Median ferritin levels were more than twice as high in patients who died compared to those who survived (1136 ng/mL vs 526 ng/mL; P < 0.001), and median NLR was also substantially elevated (17.9 vs 10.7; P < 0.001). Other laboratory abnormalities in patients who died included lower hemoglobin and platelet counts and higher white blood cell count, creatinine, bilirubin, and lactate levels.

Patients who died required more intensive interventions, with significantly higher rates of invasive ventilation (56.6% vs 33.9%; P < 0.001), vasopressor use (63.8% vs 39.3%; P < 0.001), and dialysis (24.2% vs 13.9%; P < 0.001). Despite these interventions, patients who died had longer ICU stays (7.4 days vs 5.9 days; P = 0.001) but shorter overall hospital stays (10.1 days vs 15.8 days; P < 0.001), reflecting earlier mortality.

Table 3 presents the distribution of patients across ferritin and NLR quartiles, along with associated mortality rates and median survival times. For ferritin, approximately half of the patients (49.9%) fell into the highest quartile (Q3, > 651 ng/mL), with the remainder evenly distributed between Q1 (< 277 ng/mL, 25.0%) and Q2 (277-651 ng/mL, 25.1%). Both in-hospital and 30-day mortality rates were substantially higher in the highest quartile (29.7% and 33.2%, respectively) compared to Q1 (17.8% and 21.3%) and Q2 (18.6% and 20.4%).

| Category | Total (n = 1954) | In-hospital mortality | 30-day mortality | Median survival, days (95%CI) |

| Ferritin quartiles | ||||

| Q1 (< 277 ng/mL) | 488 (25.0) | 87 (17.8) | 104 (21.3) | 87.8 (40.6-NR) |

| Q2 (277-651 ng/mL) | 490 (25.1) | 91 (18.6) | 100 (20.4) | 89.8 (58.9-NR) |

| Q3 (> 651 ng/mL) | 976 (49.9) | 290 (29.7) | 324 (33.2) | 44.4 (36.0-58.4) |

| NLR quartiles | ||||

| Q1 (< 6.8) | 484 (24.8) | 78 (16.1) | 94 (19.4) | 92.3 (53.7-NR) |

| Q2 (6.8-12.4) | 504 (25.8) | 87 (17.3) | 98 (19.4) | 91.4 (50.3-NR) |

| Q3 (> 12.4) | 966 (49.4) | 303 (31.4) | 336 (34.8) | 41.7 (32.8-55.2) |

| Combined ferritin & NLR | ||||

| Both in Q1 | 225 (11.5) | 23 (10.2) | 29 (12.9) | NR (78.6-NR) |

| Both in Q2 | 247 (12.6) | 36 (14.6) | 42 (17.0) | 98.7 (62.4-NR) |

| Mixed quartiles | 755 (38.6) | 173 (22.9) | 192 (25.4) | 65.3 (48.9-85.6) |

| Both in Q3 | 727 (37.2) | 236 (32.5) | 265 (36.5) | 37.2 (29.4-46.8) |

Similarly, for NLR, approximately half of the patients (49.4%) were in the highest quartile (Q3, > 12.4), with the remainder split between Q1 (< 6.8, 24.8%) and Q2 (6.8-12.4, 25.8%). Mortality rates were markedly elevated in the highest NLR quartile (31.4% in-hospital and 34.8% 30-day mortality) compared to Q1 (16.1% and 19.4%) and Q2 (17.3% and 19.4%).

The combined analysis of both biomarkers revealed a powerful synergistic effect. Patients with both biomarkers in the highest quartile (37.2% of the cohort) had the worst outcomes, with 32.5% in-hospital mortality, 36.5% 30-day mortality, and median survival of only 37.2 days. By contrast, those with both biomarkers in the lowest quartile (11.5% of patients) showed excellent outcomes with only 10.2% in-hospital mortality, 12.9% 30-day mortality, and median survival not reached within the study period. Patients with mixed quartile distributions (38.6%) or both biomarkers in the middle quartile (12.6%) showed intermediate outcomes, demonstrating a clear dose-response relationship.

Table 4 presents the results of univariable and multivariable Cox proportional hazards analyses for 30-day mortality. Using the highest quartile (Q3) as the reference group for both biomarkers, patients in lower ferritin quartiles showed significantly reduced hazard of death. In unadjusted analysis, the hazard ratios were 0.58 (95%CI: 0.47-0.73; P < 0.001) for Q1 and 0.59 (95%CI: 0.47-0.74; P < 0.001) for Q2. After adjustment for confounders, these protective effects remained significant but slightly attenuated (HR: 0.71, 95%CI: 0.57-0.90, P = 0.005 for Q1 and HR 0.70, 95%CI: 0.55-0.88, P = 0.002 for Q2).

| Variable | Unadjusted HR (95%CI) | P value | Adjusted HR (95%CI)1 | P value |

| Ferritin quartiles | ||||

| Q3 (highest) | Reference | - | Reference | - |

| Q1 (lowest) | 0.58 (0.47-0.73) | < 0.001 | 0.71 (0.57-0.90) | 0.005 |

| Q2 (middle) | 0.59 (0.47-0.74) | < 0.001 | 0.70 (0.55-0.88) | 0.002 |

| NLR quartiles | ||||

| Q3 (highest) | Reference | - | Reference | - |

| Q1 (lowest) | 0.65 (0.52-0.80) | < 0.001 | 0.73 (0.59-0.91) | 0.006 |

| Q2 (middle) | 0.60 (0.48-0.74) | < 0.001 | 0.63 (0.50-0.78) | < 0.001 |

| Combined ferritin & NLR | ||||

| Both in Q3 (highest) | Reference | - | Reference | - |

| Both in Q1 (lowest) | 0.42 (0.32-0.55) | < 0.001 | 0.56 (0.42-0.74) | < 0.001 |

| Mixed quartiles | 0.65 (0.53-0.80) | < 0.001 | 0.74 (0.60-0.91) | 0.005 |

| Charlson comorbidity index | ||||

| Per 1-point increase | 1.03 (1.00-1.07) | 0.048 | 1.03 (0.99-1.06) | 0.161 |

| Age | ||||

| Per 1-year increase | 1.01 (1.01-1.02) | < 0.001 | 1.02 (1.01-1.02) | < 0.001 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | Reference | - | Reference | - |

| Female | 1.08 (0.91-1.29) | 0.364 | 1.11 (0.93-1.32) | 0.258 |

| Continuous variables | ||||

| NLR (per unit) | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | 0.072 | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | 0.908 |

| Ferritin (per unit) | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | < 0.001 | 1.00 (1.00-1.00) | < 0.001 |

Similarly, lower NLR quartiles showed reduced mortality risk. Unadjusted hazard ratios were 0.65 (95%CI: 0.52-0.80; P < 0.001) for Q1 and 0.60 (95%CI: 0.48-0.74; P < 0.001) for Q2. After adjustment, these remained significant (HR: 0.73, 95%CI: 0.59-0.91, P = 0.006 for Q1) and (HR: 0.63, 95%CI: 0.50-0.78, P < 0.001 for Q2).

The combined analysis of both biomarkers provided the most striking results. Compared to patients with both biomarkers in the highest quartile, those with both biomarkers in the lowest quartile had a 58% reduction in mortality risk in unadjusted analysis (HR: 0.42, 95%CI: 0.32-0.55; P < 0.001) and a 44% reduction after adjustment (HR: 0.56, 95%CI: 0.42-0.74; P < 0.001). Patients with mixed quartile distributions showed intermediate risk reduction (adjusted HR: 0.74, 95%CI: 0.60-0.91; P = 0.005).

Older age significantly increased risk of mortality (adjusted HR: 1.02 per year, 95%CI: 1.01-1.02; P < 0.001), while sex showed no significant risk. The CCI showed a trend toward increased risk in unadjusted analysis (HR: 1.03 per point, 95%CI: 1.00-1.07; P = 0.048) but was not significant after adjustment (P = 0.161).

When analyzed as continuous variables, both ferritin and NLR showed statistically significant but clinically minimal per-unit effects, underscoring that the quartile-based approach better captures the clinical relevance of these biomarkers.

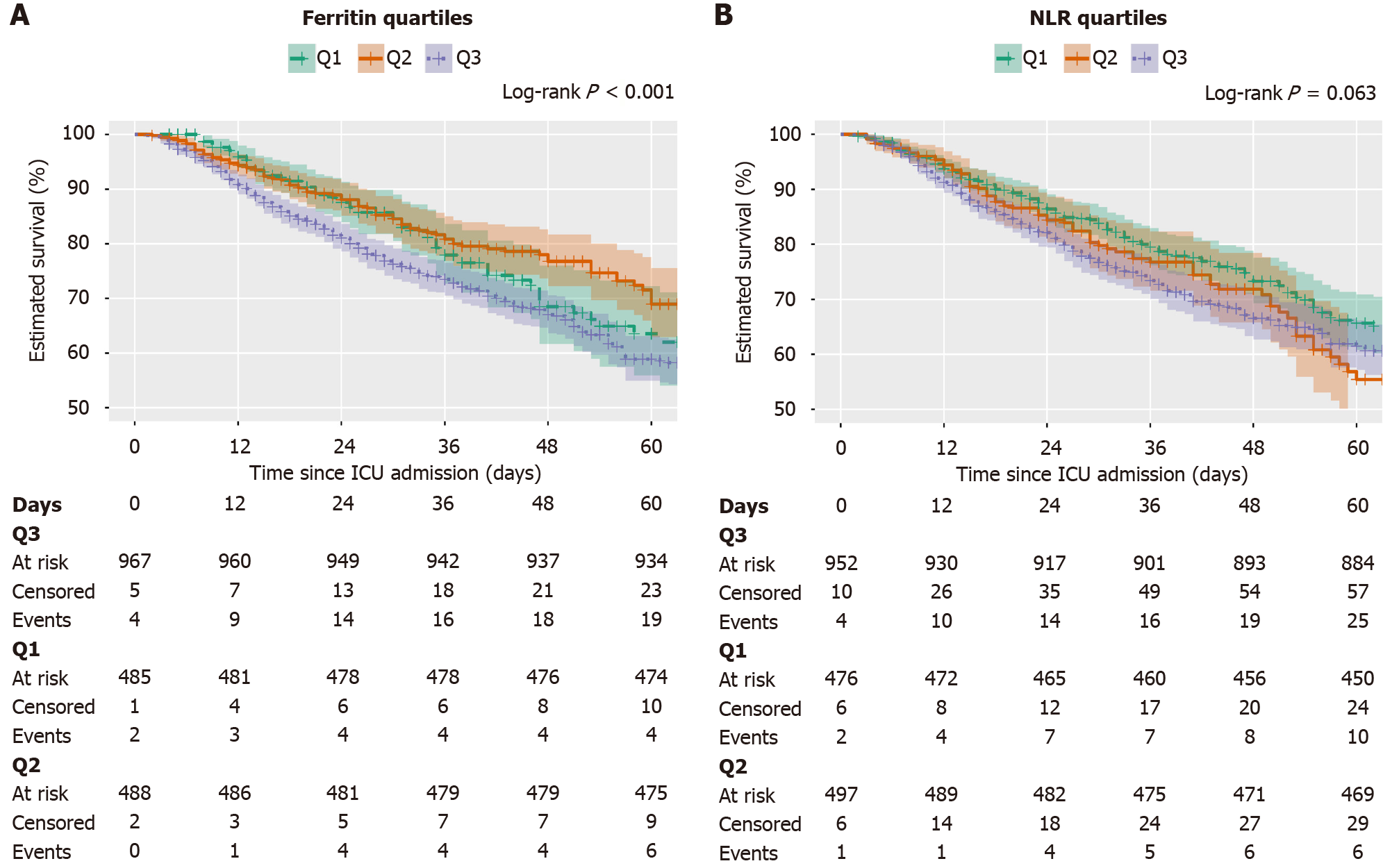

Kaplan-Meier survival curves of ferritin quartiles: Figure 2A presents Kaplan-Meier survival curves stratified by ferritin categories over time. The graph demonstrates a clear separation between survival probabilities across different ferritin levels. Patients in the high ferritin category (> 651 ng/mL) show markedly reduced survival compared to those in the low (< 277 ng/mL) and mid-range (277-651 ng/mL) ferritin categories. The median survival for patients in the high ferritin group was only 44.4 days (95%CI: 36.0-58.4), whereas neither the low nor the mid-range ferritin groups reached a median survival within the 60-day follow-up (lower 95%CI bounds 87.8 and 89.8 days, respectively). This visualization provides strong evidence that elevated ferritin levels are associated with worse survival outcomes in sepsis patients. The log-rank also reported a highly significant association between survival and ferritin values with P < 0.001.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte quartiles: Figure 2B displays Kaplan-Meier survival curves stratified by NLR quartiles. Visually, the highest NLR quartile (Q3, > 12.4) demonstrates notably worse survival compared to the lower quartiles (Q1, < 6.8 and Q2, 6.8-12.4). Patients in the highest NLR quartile exhibited a median survival of 41.7 days (95%CI: 32.8-55.2). By contrast, the lower quartiles showed considerably better survival, with median survival estimates of 92.3 days for Q1 (< 6.8) and 91.4 days for Q2 (6.8-12.4). This distinct stratification observed in the Kaplan-Meier curves underscores the potential of NLR as a valuable prognostic marker in sepsis. The log-rank test comparing survival across NLR groups yielded a borderline non-significant P value of 0.063, suggesting a trend toward differential survival that did not reach conventional statistical significance.

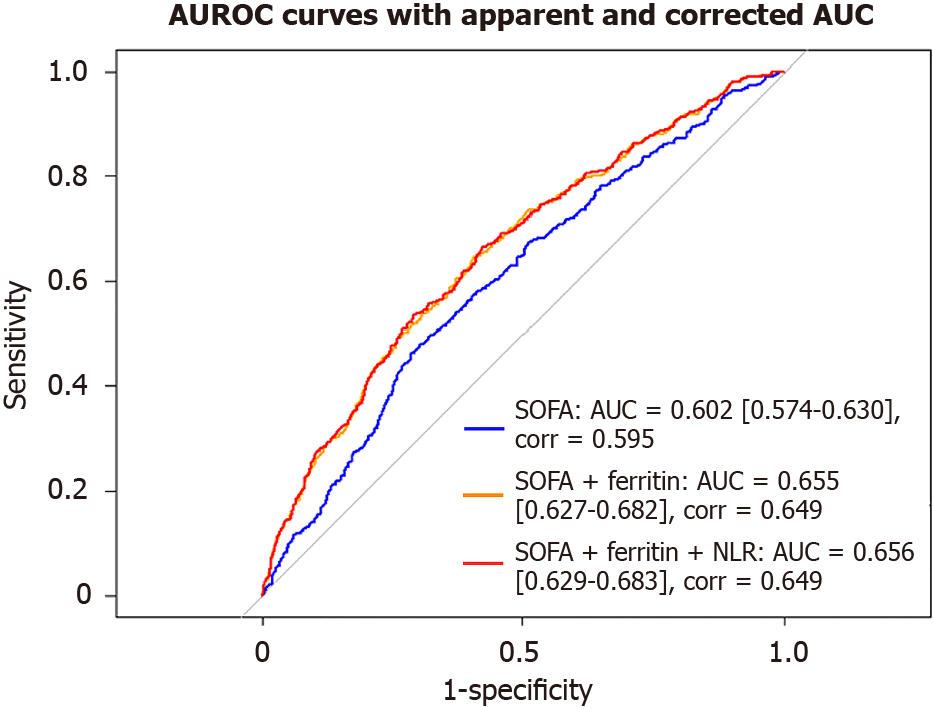

AUROC: We assessed the discriminative ability of the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score alone and in combination with serum ferritin and NLR for its association with 30-day mortality in adult patients with sepsis (Figure 3 and Table 5). The AUROC for SOFA alone was 0.602, indicating modest discriminative performance and the optimism-corrected area under the curve (AUC) was 0.595.

| Model | Apparent AUROC (95%CI) | Corrected AUROC | P value |

| SOFA alone | 0.602 (0.574-0.630) | 0.595 | Reference |

| SOFA + ferritin | 0.655 (0.627-0.628) | 0.649 | < 0.0001 |

| SOFA + ferritin + NLR | 0.656 (0.629-0.683) | 0.649 | < 0.0001 |

The combination of SOFA and serum ferritin showed a notable increase in predictive performance, with an AUC of 0.655 (95%CI: 0.627-0.682; P < 0.0001). After internal validation using bootstrap resampling, the optimism-corrected AUC was 0.648, indicating good model robustness and discrimination. The highest discrimination was observed in the model incorporating all three variables—SOFA, ferritin, and NLR—which achieved a highly significant AUC of 0.656 (95%CI: 0.629-0.683; P < 0.001). An optimism-corrected AUC of 0.650 was achieved after internal validation, indicating robust model discrimination.

These results suggest that serum ferritin contributes more significantly to risk stratification than NLR and that integrating both biomarkers with SOFA provides a modest improvement over SOFA alone. However, the overall discriminative performance of all models remained modest.

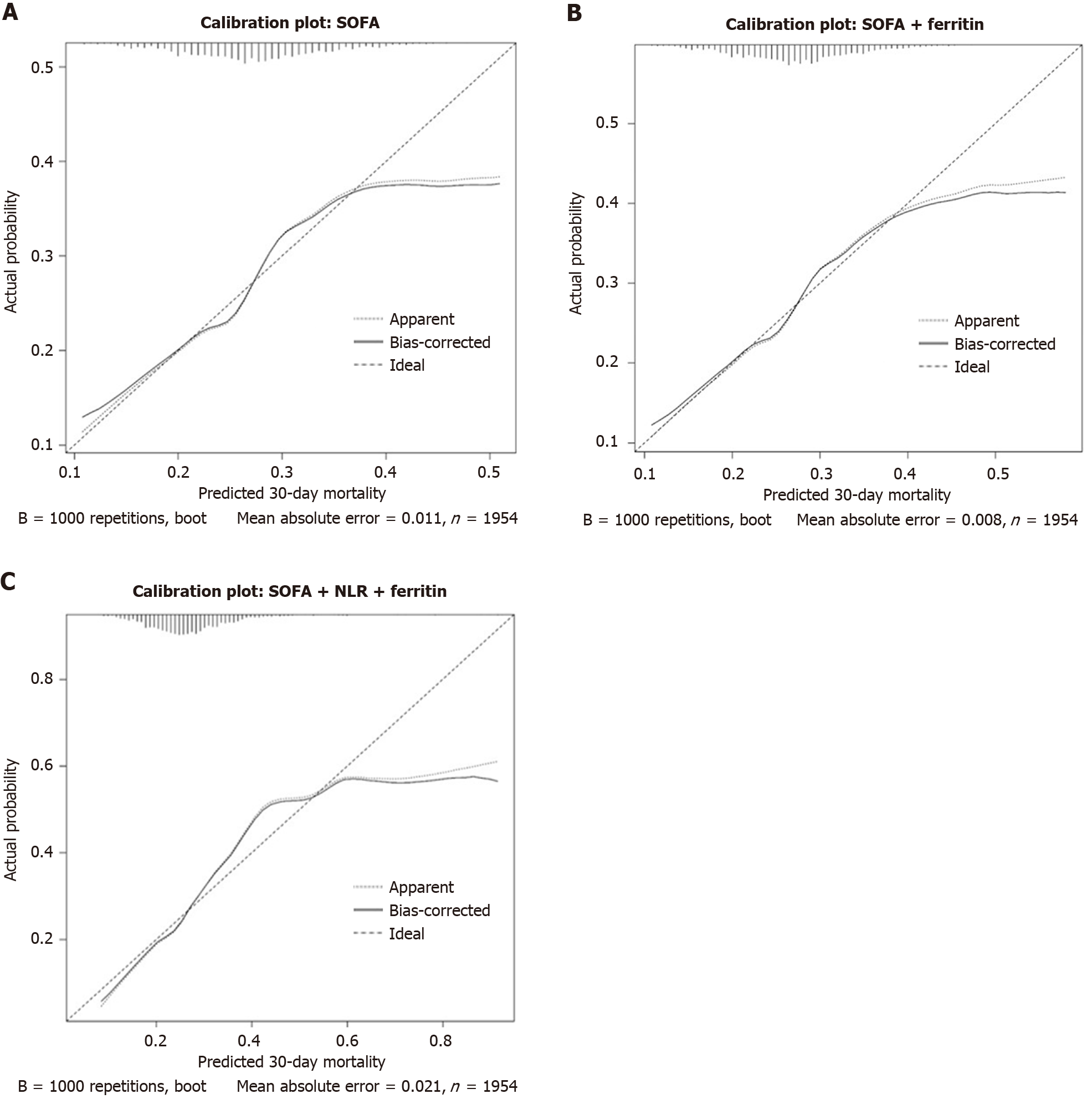

Calibration plot: The SOFA alone model (Figure 4A) showed good calibration with mean absolute error (MAE) of 0.011, indicating acceptable predictive accuracy. The addition of ferritin to SOFA model (Figure 4B) improved calibration even closer to the ideal curve throughout the probability range compared to SOFA alone model. The MAE was lower at 0.008, suggesting enhanced predictive accuracy. The SOFA + ferritin + NLR model (Figure 4C) showed increased deviation from ideal line at higher predicted probabilities, despite reasonable alignment in lower risk range. However, the MAE increased to 0.021, indicating slightly reduced calibration compared to the other two models.

NRI: The category-based NRI was calculated to assess the incremental prognostic value of ferritin and NLR in addition to SOFA. Compared to SOFA model, the addition of ferritin resulted in a statistically significant overall NRI of 0.128 (95%CI: 0.080-0.179) with NRI- (0.128; 95%CI: 0.080-0.179) and NRI+ was 0.000. The results indicate better classification of survivors than identifying deaths. The result of combined model (SOFA + ferritin + NLR) was better than SOFA + ferritin with NRI of 0.131. This suggests that our model offers improved downward classification of low-risk patients but limited value in high-risk patients. Also, addition of NLR provides slight net benefit.

In this retrospective study of adult patients admitted to the ICU with sepsis, we observed that combining serum ferritin, NLR, and the SOFA score provided significant predictive performance of 30-day mortality compared to using the SOFA score alone. The findings of this study underline the potential additive value of iron metabolism and inflammatory markers in influencing sepsis outcomes.

The SOFA score has demonstrated solid predictive value for mortality and has been validated by numerous studies[21-23]. However, the sole reliance of the SOFA score on physiological parameters may exclude the influence of immunological dysregulation and systemic inflammatory burden, which are the central features of sepsis pathophysiology[24]. Our results suggest that the inclusion of immune and inflammatory status markers, such as NLR and serum ferritin, adds prognostic granularity beyond the SOFA score.

Many previous studies have evaluated the prognostic relevance of serum ferritin and NLR separately[25-28]. Elevated NLR has been associated with increased mortality in critically ill patients with sepsis[28]. This result reflects neutrophil-driven inflammation and relative lymphopenia, which are the hallmarks of sepsis-induced immune dysfunction[29]. Similarly, beyond its role in iron metabolism, serum ferritin acts as an acute-phase reactant and may reflect hyperinflammation or macrophage activation syndrome[30]. Prior studies have analyzed serum ferritin as an independent predictor of sepsis severity and mortality, which is consistent with our study[25,26,31]. Mechanistically, sepsis-induced cytokine release and endotoxemia stimulate ferritin synthesis, reflecting macrophage activation in iron homeostasis. High ferritin levels may exacerbate tissue injury via iron-mediated oxidative stress and ferroptosis, and may contribute to immunosuppression through dysregulated iron metabolism[30]. Moreover, ferritin-driven pathways have been implicated in promoting neutrophil extracellular trap formation, further amplifying organ dysfunction in sepsis-associated injury[32]. These insights support our quartile-based approach and underscores the importance of defining clinically meaningful ferritin thresholds.

In our cohort, patients who died were older and had higher CCI than survivors, consistent with prior studies indicating older age and higher comorbidity burden as strong predictor of sepsis mortality[33,34]. The observed differences in infection source, with pulmonary infections more prevalent among patients who died, aligns with studies showing respiratory foci confers poor outcomes compared to other sources[35]. Hemodynamic parameters like lower blood pressure and higher heart and respiratory rates among patients who died aligning with previously studies showing increased mortality risk[36]. The greater need for invasive interventions (ventilation, vasopressors, dialysis) among dead patients reflects organ dysfunction at baseline, aligning with Sepsis-3 emphasis on organ failure severity for prognostication[37]. Also, the longer ICU but shorter hospital stays in dead patients likely reflects early in-hospital mortality.

Recent literature shows an increased trend of developing multi-dimensional risk models incorporating laboratory biomarkers and clinical scores, which aligns with our study[38-40]. Individual quartile-based comparisons showed statistically significant hazard reductions in lower serum ferritin and NLR groups. However, the most notable outcome came from the combined lowest quartile groups, indicating synergistic power.

Our study’s combined model demonstrates significantly improved predictive performance incorporating serum ferritin, NLR, and SOFA over SOFA. The AUROC curve for SOFA score alone was 0.602. An AUROC of 0.655 was ob

The calibration analyses also demonstrated that SOFA alone had good agreement between predicted and observed risk across most probability range with MAE of 0.011. Adding ferritin improved calibration by reducing MAE to 0.008 and bringing predictions closer to ideal line. Although, the SOFA + ferritin + NLR model remained well calibrated at lower risk, it deviated more from the ideal line at higher predicted probabilities, increasing MAE to 0.021. This indicates that while ferritin enhances calibration over SOFA alone, inclusion of NLR may introduce modest miscalibration in patients who are high risk.

The net reclassification improvement (NRI) results were also demonstrated using our combined model to improve risk stratification. The value of 0.131 indicated a modest but significant reclassification improvement over the SOFA score alone, demonstrating the better ability to accurately stratify patients into lower risk categories but limited value for high-risk patients. This finding is consistent with other studies that integrate biomarkers for risk predictions, where NRI is used to assess the integration of new predictors in clinical models[42].

Many prior studies have used the MIMIC database for developing prognostic models[39,43]. For instance, a model developed by Zhang et al[43] predicting 28-day mortality in patients with sepsis or sepsis associated delirium achieved an AUC of 0.91 in development and AUC of 0.83 in validation cohorts. A study by Yang et al[39] identified SOFA, age and parameters like anion gap, International Normalized Ratio, hemoglobin A1c among others as independent predictors in patients with sepsis and diabetes mellitus. Although these models showed better performance, these models require extensive data inputs, which may limit applicability in low-resource settings. Our study instead focuses on a simpler logistic model adding only two readily available biomarkers, serum ferritin and NLR, to SOFA and basic covariates (age, sex, CCI). Although the resulting AUC is modest compared to other sepsis models, our model offers a balance between improved performance over SOFA alone and feasibility in resource-limited settings.

Our study contributes to the limited but growing body of literature that uses a large critical care database to assess the combined impact of easily accessible serum ferritin and NLR in the ICU setting. This is among the first studies that use the MIMIC-IV database to evaluate such a simple model involving both NLR and ferritin. The detailed, time-stamped laboratory data of patients in the ICU makes the MIMIC-IV database ideal for this study.

There are also applications for our findings. Our proposed approach can be widely used, particularly in settings with low resources, because serum ferritin and NLR are both easily accessible and reasonably priced laboratory parameters. Moreover, this model might also help with early risk assessment and well-informed clinical judgment. Our model's integration into ICU triage tools or electronic medical records may provide physicians with real-time risk estimation, which would reduce the need for expensive diagnostics to provide precision care. Moreover, it can also serve as a screening tool for early inclusion in clinical trials in sepsis targeting immune modulation. Our model can also serve as a real-time alert within the ICU dashboard, potentially guiding decisions for at-risk sepsis patients.

The large sample size, rigorous exclusion criteria, and well-defined outcomes strengthen our study. This study and limitations. First, there is a need for external validation of our study. Second, there was also potential residual confounding due to the study's retrospective nature. Third, there may be some bias due to the proportion of data excluded for missing variables because of rigorous exclusion. Also, due to lack of universally accepted clinical thresholds, we stratified ferritin and NLR by quartiles. The performance of our model was modest, but it offers a balance between performance and feasibility in resource-limited settings.

In this work, we used Cox proportional hazards regression, which yields reliable time-to-event analysis, corrected for age, sex, and the CCI, among other possible confounders. Future work should test for time-varying covariate effects to verify proportionality assumptions. In addition, the lack of dynamic biomarker tracking may limit the ability to assess the prognostic value of serial serum ferritin or NLR measurements, which may change during ICU stay. Future research should also focus on integrating dynamic time-varying parameters, including the trajectory of serum ferritin and NLR over time, and validating our model in different cohorts. Additionally, prospective studies should incorporate immunological profiling, which may uncover insights that explain the prognostic relationships observed here.

In this retrospective cohort of critically ill patients, lower levels of serum ferritin and NLR showed significantly reduced 30-day mortality risk, with the combination of both markers in the lowest quartile conferring the greatest survival benefit. Integrating ferritin and NLR with the SOFA score modestly improved performance of model, with this improvement predominantly driven by ferritin, suggesting that it may be a more robust inflammatory marker for mortality risk stratification than NLR. Given the routine availability and low cost of ferritin and complete blood count (for NLR), this biomarker-based approach may serve as a practical and accessible tool to support early risk assessment and triage, particularly in resource-limited critical care settings. Incorporating these markers into routine evaluation may help guide timely interventions and prioritize care for patients who are at high risk, ultimately contributing to improved outcomes in vulnerable populations.

| 1. | Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, Shankar-Hari M, Annane D, Bauer M, Bellomo R, Bernard GR, Chiche JD, Coopersmith CM, Hotchkiss RS, Levy MM, Marshall JC, Martin GS, Opal SM, Rubenfeld GD, van der Poll T, Vincent JL, Angus DC. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315:801-810. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15803] [Cited by in RCA: 18883] [Article Influence: 1888.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 2. | Rhodes A, Evans LE, Alhazzani W, Levy MM, Antonelli M, Ferrer R, Kumar A, Sevransky JE, Sprung CL, Nunnally ME, Rochwerg B, Rubenfeld GD, Angus DC, Annane D, Beale RJ, Bellinghan GJ, Bernard GR, Chiche JD, Coopersmith C, De Backer DP, French CJ, Fujishima S, Gerlach H, Hidalgo JL, Hollenberg SM, Jones AE, Karnad DR, Kleinpell RM, Koh Y, Lisboa TC, Machado FR, Marini JJ, Marshall JC, Mazuski JE, McIntyre LA, McLean AS, Mehta S, Moreno RP, Myburgh J, Navalesi P, Nishida O, Osborn TM, Perner A, Plunkett CM, Ranieri M, Schorr CA, Seckel MA, Seymour CW, Shieh L, Shukri KA, Simpson SQ, Singer M, Thompson BT, Townsend SR, Van der Poll T, Vincent JL, Wiersinga WJ, Zimmerman JL, Dellinger RP. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock: 2016. Crit Care Med. 2017;45:486-552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1784] [Cited by in RCA: 2034] [Article Influence: 226.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Liu VX, Fielding-Singh V, Greene JD, Baker JM, Iwashyna TJ, Bhattacharya J, Escobar GJ. The Timing of Early Antibiotics and Hospital Mortality in Sepsis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;196:856-863. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 551] [Cited by in RCA: 694] [Article Influence: 77.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | World Health Organization. WHO calls for global action on sepsis – cause of 1 in 5 deaths worldwide. Sep 8, 2020. [cited 10 April 2025]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news/item/08-09-2020-who-calls-for-global-action-on-sepsis---cause-of-1-in-5-deaths-worldwide. |

| 5. | Rudd KE, Johnson SC, Agesa KM, Shackelford KA, Tsoi D, Kievlan DR, Colombara DV, Ikuta KS, Kissoon N, Finfer S, Fleischmann-Struzek C, Machado FR, Reinhart KK, Rowan K, Seymour CW, Watson RS, West TE, Marinho F, Hay SI, Lozano R, Lopez AD, Angus DC, Murray CJL, Naghavi M. Global, regional, and national sepsis incidence and mortality, 1990-2017: analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet. 2020;395:200-211. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2870] [Cited by in RCA: 4975] [Article Influence: 829.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (7)] |

| 6. | Mahapatra S, Heffner AC. Septic Shock. 2023 Jun 12. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2025 Jan. [PubMed] |

| 7. | Pierrakos C, Velissaris D, Bisdorff M, Marshall JC, Vincent JL. Biomarkers of sepsis: time for a reappraisal. Crit Care. 2020;24:287. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 118] [Cited by in RCA: 440] [Article Influence: 73.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Evans L, Rhodes A, Alhazzani W, Antonelli M, Coopersmith CM, French C, Machado FR, Mcintyre L, Ostermann M, Prescott HC, Schorr C, Simpson S, Wiersinga WJ, Alshamsi F, Angus DC, Arabi Y, Azevedo L, Beale R, Beilman G, Belley-Cote E, Burry L, Cecconi M, Centofanti J, Coz Yataco A, De Waele J, Dellinger RP, Doi K, Du B, Estenssoro E, Ferrer R, Gomersall C, Hodgson C, Hylander Møller M, Iwashyna T, Jacob S, Kleinpell R, Klompas M, Koh Y, Kumar A, Kwizera A, Lobo S, Masur H, McGloughlin S, Mehta S, Mehta Y, Mer M, Nunnally M, Oczkowski S, Osborn T, Papathanassoglou E, Perner A, Puskarich M, Roberts J, Schweickert W, Seckel M, Sevransky J, Sprung CL, Welte T, Zimmerman J, Levy M. Surviving Sepsis Campaign: International Guidelines for Management of Sepsis and Septic Shock 2021. Crit Care Med. 2021;49:e1063-e1143. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 306] [Cited by in RCA: 1711] [Article Influence: 342.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 9. | Acar C, Bozgul SMK, Yuksel HC, Bozkurt D. Outcomes of patients with sepsis due extensively drug-resistant bacterial infections with and without polyspecific intravenous immunoglobulin therapy: A retrospective study. Medicine (Baltimore). 2025;104:e42190. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Bottari G, Ranieri VM, Ince C, Pesenti A, Aucella F, Scandroglio AM, Ronco C, Vincent JL. Use of extracorporeal blood purification therapies in sepsis: the current paradigm, available evidence, and future perspectives. Crit Care. 2024;28:432. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Chen Q, Gao M, Yang H, Mei L, Zhong R, Han P, Liu P, Zhao L, Wang J, Li J. Serum ferritin levels are associated with advanced liver fibrosis in treatment-naive autoimmune hepatitis. BMC Gastroenterol. 2022;22:23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Lalueza A, Ayuso B, Arrieta E, Trujillo H, Folgueira D, Cueto C, Serrano A, Laureiro J, Arévalo-Cañas C, Castillo C, Díaz-Pedroche C, Lumbreras C; INFLUDOC group. Elevation of serum ferritin levels for predicting a poor outcome in hospitalized patients with influenza infection. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26:1557.e9-1557.e15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | McCullough K, Bolisetty S. Iron Homeostasis and Ferritin in Sepsis-Associated Kidney Injury. Nephron. 2020;144:616-620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Liang P, Yu F. Value of CRP, PCT, and NLR in Prediction of Severity and Prognosis of Patients With Bloodstream Infections and Sepsis. Front Surg. 2022;9:857218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Spoto S, Lupoi DM, Valeriani E, Fogolari M, Locorriere L, Beretta Anguissola G, Battifoglia G, Caputo D, Coppola A, Costantino S, Ciccozzi M, Angeletti S. Diagnostic Accuracy and Prognostic Value of Neutrophil-to-Lymphocyte and Platelet-to-Lymphocyte Ratios in Septic Patients outside the Intensive Care Unit. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021;57:811. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 6.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Li Y, Wang J, Wei B, Zhang X, Hu L, Ye X. Value of Neutrophil:Lymphocyte Ratio Combined with Sequential Organ Failure Assessment Score in Assessing the Prognosis of Sepsis Patients. Int J Gen Med. 2022;15:1901-1908. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Johnson A, Bulgarelli L, Pollard T, Gow B, Moody B, Horng S, Celi LA, Mark R. MIMIC-IV (version 3.1). PhysioNet. 2024. Available from: https://physionet.org/content/mimiciv/3.1/. |

| 18. | Goldberger AL, Amaral LA, Glass L, Hausdorff JM, Ivanov PC, Mark RG, Mietus JE, Moody GB, Peng CK, Stanley HE. PhysioBank, PhysioToolkit, and PhysioNet: components of a new research resource for complex physiologic signals. Circulation. 2000;101:E215-E220. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7935] [Cited by in RCA: 5505] [Article Influence: 211.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 19. | Johnson AEW, Bulgarelli L, Shen L, Gayles A, Shammout A, Horng S, Pollard TJ, Hao S, Moody B, Gow B, Lehman LH, Celi LA, Mark RG. MIMIC-IV, a freely accessible electronic health record dataset. Sci Data. 2023;10:1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1407] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 20. | Quan H, Sundararajan V, Halfon P, Fong A, Burnand B, Luthi JC, Saunders LD, Beck CA, Feasby TE, Ghali WA. Coding algorithms for defining comorbidities in ICD-9-CM and ICD-10 administrative data. Med Care. 2005;43:1130-1139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6122] [Cited by in RCA: 8762] [Article Influence: 417.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Vincent JL, Moreno R, Takala J, Willatts S, De Mendonça A, Bruining H, Reinhart CK, Suter PM, Thijs LG. The SOFA (Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment) score to describe organ dysfunction/failure. On behalf of the Working Group on Sepsis-Related Problems of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Intensive Care Med. 1996;22:707-710. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6591] [Cited by in RCA: 8128] [Article Influence: 270.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (11)] |

| 22. | Freund Y, Lemachatti N, Krastinova E, Van Laer M, Claessens YE, Avondo A, Occelli C, Feral-Pierssens AL, Truchot J, Ortega M, Carneiro B, Pernet J, Claret PG, Dami F, Bloom B, Riou B, Beaune S; French Society of Emergency Medicine Collaborators Group. Prognostic Accuracy of Sepsis-3 Criteria for In-Hospital Mortality Among Patients With Suspected Infection Presenting to the Emergency Department. JAMA. 2017;317:301-308. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 422] [Cited by in RCA: 489] [Article Influence: 54.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Cárdenas-Turanzas M, Ensor J, Wakefield C, Zhang K, Wallace SK, Price KJ, Nates JL. Cross-validation of a Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score-based model to predict mortality in patients with cancer admitted to the intensive care unit. J Crit Care. 2012;27:673-680. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 3.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Seymour CW, Liu VX, Iwashyna TJ, Brunkhorst FM, Rea TD, Scherag A, Rubenfeld G, Kahn JM, Shankar-Hari M, Singer M, Deutschman CS, Escobar GJ, Angus DC. Assessment of Clinical Criteria for Sepsis: For the Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315:762-774. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3076] [Cited by in RCA: 2667] [Article Influence: 266.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Fang YP, Zhang HJ, Guo Z, Ren CH, Zhang YF, Liu Q, Wang Z, Zhang X. Effect of Serum Ferritin on the Prognosis of Patients with Sepsis: Data from the MIMIC-IV Database. Emerg Med Int. 2022;2022:2104755. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | He L, Guo C, Su Y, Ding N. The relationship between serum ferritin level and clinical outcomes in sepsis based on a large public database. Sci Rep. 2023;13:8677. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Huang Z, Fu Z, Huang W, Huang K. Prognostic value of neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio in sepsis: A meta-analysis. Am J Emerg Med. 2020;38:641-647. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 98] [Cited by in RCA: 357] [Article Influence: 51.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Hwang SY, Shin TG, Jo IJ, Jeon K, Suh GY, Lee TR, Yoon H, Cha WC, Sim MS. Neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio as a prognostic marker in critically-ill septic patients. Am J Emerg Med. 2017;35:234-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 160] [Article Influence: 16.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Pierrakos C, Vincent JL. Sepsis biomarkers: a review. Crit Care. 2010;14:R15. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 813] [Cited by in RCA: 907] [Article Influence: 56.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Rosário C, Zandman-Goddard G, Meyron-Holtz EG, D'Cruz DP, Shoenfeld Y. The hyperferritinemic syndrome: macrophage activation syndrome, Still's disease, septic shock and catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome. BMC Med. 2013;11:185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 298] [Cited by in RCA: 339] [Article Influence: 26.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Su L, Han B, Liu C, Liang L, Jiang Z, Deng J, Yan P, Jia Y, Feng D, Xie L. Value of soluble TREM-1, procalcitonin, and C-reactive protein serum levels as biomarkers for detecting bacteremia among sepsis patients with new fever in intensive care units: a prospective cohort study. BMC Infect Dis. 2012;12:157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 95] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Zhang H, Wu D, Wang Y, Shi Y, Shao Y, Zeng F, Spencer CB, Ortoga L, Wu D, Miao C. Ferritin-mediated neutrophil extracellular traps formation and cytokine storm via macrophage scavenger receptor in sepsis-associated lung injury. Cell Commun Signal. 2024;22:97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Tang J, Huang J, He X, Zou S, Gong L, Yuan Q, Peng Z. The prediction of in-hospital mortality in elderly patients with sepsis-associated acute kidney injury utilizing machine learning models. Heliyon. 2024;10:e26570. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Huang Y, Gao Y, Quan S, Pan H, Wang Y, Dong Y, Ye L, Wu M, Zhou A, Ruan X, Wang B, Chen J, Zheng C, Xu H, Lu Y, Pan J. Development and Internal-External Validation of the Acci-Sofa Model for Predicting In-Hospital Mortality of Patients with Sepsis-3 In the ICU: A Multicenter Retrospective Cohort Study. Shock. 2024;61:367-374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | He XL, Liao XL, Xie ZC, Han L, Yang XL, Kang Y. Pulmonary Infection Is an Independent Risk Factor for Long-Term Mortality and Quality of Life for Sepsis Patients. Biomed Res Int. 2016;2016:4213712. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 2.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Chen Q, Li W, Wang Y, Chen X, He D, Liu M, Yuan J, Xiao C, Li Q, Chen L, Shen F. Investigating the Association Between Mean Arterial Pressure on 28-Day Mortality Risk in Patients With Sepsis: Retrospective Cohort Study Based on the MIMIC-IV Database. Interact J Med Res. 2025;14:e63291. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Hou N, Li M, He L, Xie B, Wang L, Zhang R, Yu Y, Sun X, Pan Z, Wang K. Predicting 30-days mortality for MIMIC-III patients with sepsis-3: a machine learning approach using XGboost. J Transl Med. 2020;18:462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 319] [Cited by in RCA: 349] [Article Influence: 58.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 38. | Wu J, Liang J, An S, Zhang J, Xue Y, Zeng Y, Li L, Luo J. Novel biomarker panel for the diagnosis and prognosis assessment of sepsis based on machine learning. Biomark Med. 2022;16:1129-1138. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Yang C, Jiang Y, Zhang C, Min Y, Huang X. The predictive values of admission characteristics for 28-day all-cause mortality in septic patients with diabetes mellitus: a study from the MIMIC database. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1237866. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Li C, Zhao K, Ren Q, Chen L, Zhang Y, Wang G, Xie K. Development and validation of a model for predicting in-hospital mortality in patients with sepsis-associated kidney injury receiving renal replacement therapy: a retrospective cohort study based on the MIMIC-IV database. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2024;14:1488505. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Xie Y, Li B, Lin Y, Shi F, Chen W, Wu W, Zhang W, Fei Y, Zou S, Yao C. Combining Blood-Based Biomarkers to Predict Mortality of Sepsis at Arrival at the Emergency Department. Med Sci Monit. 2021;27:e929527. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Salomaa V, Havulinna A, Saarela O, Zeller T, Jousilahti P, Jula A, Muenzel T, Aromaa A, Evans A, Kuulasmaa K, Blankenberg S. Thirty-one novel biomarkers as predictors for clinically incident diabetes. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10100. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 130] [Cited by in RCA: 138] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Zhang L, Li X, Huang J, Yang Y, Peng H, Yang L, Yu X. Predictive model of risk factors for 28-day mortality in patients with sepsis or sepsis-associated delirium based on the MIMIC-IV database. Sci Rep. 2024;14:18751. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/