Published online Mar 18, 2026. doi: 10.5500/wjt.v16.i1.113034

Revised: September 18, 2025

Accepted: November 26, 2025

Published online: March 18, 2026

Processing time: 154 Days and 10.9 Hours

Robotic assistance is increasingly used for donor and recipient hepatectomy in liver transplantation, yet existing evidence is fragmented and variably indirect.

To evaluate clinical outcomes, surgical performance, and economic effects of robotic-assisted donor and recipient hepatectomy in the transplant pathway.

Following Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses 2020 and a priori registration, systematic reviews were included with or without meta-analysis. Four databases were searched through July 2025. Methodological quality was appraised with a measurement tool to assess systematic reviews (AMSTAR 2), and certainty was graded with grading of recommendations asse

Five reviews met the inclusion criteria, four with meta-analyses and one consensus review used only for context. Donor (direct) findings were more favorable for robotics in terms of estimated blood loss (≈ -117 mL) and length of stay (≈ -0.6 days), although with longer operative time (≈ +105 minutes). Absolute risks for donor complications were not estimable from ratio-only data. Recipient (indirect) meta-analysis indicated robotics to be favorable in terms of conversion (RR ≈ 0.41) and severe morbidity (RR ≈ 0.81), with a trend toward lower overall morbidity (RR ≈ 0.92) and no difference in 30-day mortality. Differences in length of stay and operative time were small and heterogeneous. Economic evidence (indirect, network meta-analysis) suggested higher procedural costs for robotic vs laparoscopic intervention, but lower hospitalization costs vs open intervention, with laparoscopy the least expensive overall. AMSTAR 2 ratings were moderate-to-high across the reviews, GRADE certainty was low for key donor continuous outcomes, and low-to-moderate for recipient and economic outcomes. Overlap was slight (graded-corpus CCA = 0.0%; including a contextual non-transplant review increased CCA to ≈ 1.25%).

Robotic donor hepatectomy confers perioperative advantages at the cost of longer operative time. Recipient and economic findings are indirect and considered hypothesis-generating. Transplant-specific, prospective com

Core Tip: This umbrella review separates donor (direct) from recipient/economic (indirect) evidence and standardizes effect reporting, heterogeneity, and grading of recommendations assessment, development and evaluation (GRADE). Donor robotics reduces blood loss and length of stay but lengthens operative time. Recipient robotics shows fewer conversions to open intervention and lower severe morbidity, with no mortality difference. Economic contrasts are context-dependent, with higher procedural but lower hospitalization costs for robotic vs open, and laparoscopy the least expensive overall. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses counts, citation-matrix/corrected covered area, AMSTAR 2, and outcome-level GRADE profiles are provided to ensure an audit-ready package and to map evidence gaps that future transplant-specific studies must address.

- Citation: Ardila CM, González-Arroyave D, Ramírez-Arbelaez J. Robotic-assisted donor and recipient hepatectomy in liver transplantation: An umbrella review of clinical outcomes, surgical performance, and cost-effectiveness. World J Transplant 2026; 16(1): 113034

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3230/full/v16/i1/113034.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5500/wjt.v16.i1.113034

Liver transplantation remains the definitive therapy for end-stage liver disease and select hepatic malignancies[1]. Yet, the persistent gap between organ demand and supply has compelled many programs to expand living donor liver transplantation (LDLT). In LDLT, the donor - an otherwise healthy individual - is exposed to a major hepatectomy purely for altruistic benefit to the recipient. Consequently, minimizing surgical trauma and perioperative risk is ethically paramount[2]. Traditional open donor and recipient hepatectomies, while effective, are associated with substantial surgical trauma, postoperative pain, wound complications, and prolonged convalescence[3,4]. These limitations have driven the development and dissemination of minimally invasive liver surgery in transplantation, first via laparoscopy and, increasingly, through robot-assisted platforms[5,6].

Robotic-assisted liver surgery leverages three-dimensional visualization, tremor filtration, and articulating instruments with enhanced degrees of freedom[3,4]. These features facilitate precise dissection and intracorporeal suturing in deep or constrained operative fields, and may shorten learning curves for complex maneuvers[3,6]. In living donors, pioneering series and comparative cohorts have shown that robotic living donor right hepatectomy (RLDRH) achieves lower estimated blood loss and comparable overall morbidity vs open or laparoscopy-assisted techniques, albeit with longer operative time. For instance, Rho et al[4] compared 52 consecutive RLDRH cases with 62 conventional open and 118 laparoscopy-assisted donor right hepatectomies, finding markedly reduced blood loss with RLDRH while maintaining similar complication rates and improved body-image scores. Single-center experiences, including the pure minimally invasive robotic donor right hepatectomy technique described by Chen et al[6], have further established feasibility and reproducible steps for safe vascular and biliary control. Large programmatic reports have subsequently demonstrated the reproducibility of robotic donor hepatectomy across complex anatomies and graft types, including a 501-case single-center experience in which accrued expertise allowed most donor hepatectomies to be performed robotically with favorable donor-reported outcomes[5].

The successful dissemination of robotic donor hepatectomy depends on structured training, mentorship, and standardization. A multicenter learning-curve analysis by Cheah et al[7] estimated that stabilization of operative times for robotic donor right hepatectomy occurred after approximately 9-17 cases across two high-volume hepato-pancreato-biliary (HPB)/transplant centers, with predominantly minor complication rates that trended lower after the learning phase. Similarly, early-adopter centers in North America have shown that a stepwise implementation - beginning with hybrid cases under proctorship and progressing to fully robotic procedures - can be achieved safely even in lower-volume LDLT programs, yielding lower blood loss but longer operative times compared with open surgery, while maintaining comparable short-term outcomes[8].

At a broader population level, an international registry analysis reported that robotic donor hepatectomy was associated not only with lower donor morbidity but also with reduced major recipient morbidity compared with laparoscopic or open donor surgery, suggesting potential downstream benefits for recipients when the donor procedure is robotic[9]. However, robust comparative effectiveness data for fully robotic recipient operations remain sparse, and standardized indications, safety thresholds, and economic implications are yet to be clearly defined.

Beyond the immediate surgical outcomes, contemporary literature emphasizes that performance metrics should be interpreted alongside economic considerations that influence the sustainability of transplantation programs. From an economic perspective, organ transplantation - particularly in high-cost, technology-intensive modalities such as robotic surgery - requires evaluation within a cost-utility framework that considers both direct procedural expenditures and the broader societal and health system returns. International health policy analyses have highlighted that, when integrated into universal health coverage, transplantation can generate long-term economic benefits by reducing the burden of chronic organ failure, improving patient productivity, and decreasing downstream healthcare expenditures, provided that initial investment and program sustainability are secured through robust funding mechanisms[10,11]. In this context, robotic-assisted donor and recipient hepatectomy presents a nuanced trade-off: It may confer perioperative performance advantages and potentially enhance donor and recipient outcomes, but often at higher upfront cost - reinforcing the need for dedicated cost-effectiveness and cost-utility assessments in the transplant setting, where donor safety and recipient benefit drive value-based care decisions.

Despite these promising signals, the transplant literature on robotic-assisted hepatectomy is fragmented by population (donors vs recipients), graft type (right vs left lobe/segmental grafts), center volume and expertise, and heterogeneity in outcome definitions and reporting. Multiple studies focus exclusively on donors[3,12] or on non-transplant liver resections[13], limiting direct applicability to recipient operations. Across reviews, the overlap of primary cohorts is rarely quantified, the risk of bias varies, and certainty of evidence is inconsistently graded[3,12]. Furthermore, economic evaluations incorporate heterogeneous cost components and currencies[14,15], complicating cross-study comparisons. These limitations underscore the need for a rigorous, higher-level synthesis to consolidate the totality of evidence, benchmark methodological quality, and map evidentiary gaps.

To date, there is no comprehensive umbrella review dedicated to robotic-assisted donor and recipient hepatectomy in liver transplantation that integrates clinical outcomes, surgical performance, and cost-effectiveness while appraising review quality, grading certainty, and quantifying primary-study overlap. Such a synthesis is essential to inform practice standards, guide training and credentialing pathways, support technology adoption, and direct health-system inve

Accordingly, the overarching objective of this umbrella review is to evaluate, across published systematic reviews and meta-analyses, the comparative clinical outcomes, surgical performance metrics, and cost-effectiveness of robotic-assisted hepatectomy in both living liver donors and transplant recipients vis-à-vis laparoscopic and open approaches. By delivering a rigorous, consolidated synthesis, this work intends to inform clinical decision-making, credentialing frameworks, and resource allocation for the safe and effective adoption of robotic technology in liver transplantation.

This umbrella review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2020 recommendations for reviews of reviews and aligned with methodological guidance from the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions[16,17]. A protocol was developed a priori and prospectively registered in PROSPERO (CRD420251122560), specifying the review question, eligibility framework, outcomes, and analytic plan.

We included systematic reviews with or without quantitative synthesis (pairwise or network meta-analysis) that evaluated robotic-assisted donor or recipient hepatectomy within the context of liver transplantation and compared it against laparoscopic and/or open surgery. Reviews were eligible irrespective of language or publication year, provided they reported at least one outcome within the prespecified domains (clinical, surgical performance, or economic).

The four Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes and Study elements were defined as follows: Participants (P): Patients undergoing robotic-assisted hepatectomy within the context of liver transplantation - either living liver donors (robotic donor hepatectomy) or transplant recipients (robotic recipient hepatectomy). Reviews with mixed donor and recipient populations were eligible only when transplant-specific data were reported separately by population or could be reliably extracted. Interventions (I): Clinically deployed multi-arm robotic platforms performing donor or recipient hepatectomy. Comparators (C): Laparoscopic and/or open hepatectomy. Outcomes (O): Primary outcomes: Overall postoperative morbidity; major complications (Clavien-Dindo ≥ III); 30day or inhospital mortality. Secondary outcomes: Operative time; conversion to open surgery; length of hospital stay; blood loss and transfusion; R0 resection rate; economic outcomes (cost-morbidity, cost-mortality, cost-efficacy); readmission or reoperation; graft outcomes (if reported). In addition, we extracted review-reported surgical indications, case selection criteria, and safety thresholds when available, given their relevance to standardization of practice. Study design (S): Systematic reviews and meta-analyses (including network meta-analyses).

This umbrella synthesizes comparative evidence on robotic-assisted donor hepatectomy in living liver donors and recipient hepatectomy within the liver-transplant pathway vs laparoscopic and/or open techniques. Eligible evidence for graded synthesis is restricted to systematic reviews (with or without meta-analysis) that meet the above Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcomes and Study. Mixed populations were eligible only when transplant-specific adult data were reported separately or could be reliably extracted.

We excluded single-arm case series, experimental/prototype platforms, simulation or learning-curve-only reports, conference abstracts without extractable data, narrative/scoping reviews without systematic methods, editorials/Letters, and systematic reviews that did not disaggregate robotic results from other minimally invasive techniques or failed to separate transplant-specific cohorts. Primary studies were not eligible unless they contributed data within an otherwise eligible systematic review.

A comprehensive search of PubMed (MEDLINE), Scopus, Web of Science, and EMBASE was conducted from inception through July 2025, without language restrictions. We combined controlled vocabulary (e.g., Robotic Surgical Procedures, Hepatectomy, Liver Transplantation) with free-text synonyms (e.g., robot, “da Vinci”, hepatectom, “liver resection”, sectionectomy/segmentectomy, “donor/recipient hepatectomy”, explant). An a priori systematic review/meta-analysis filter was applied in all databases. Full dated strings are provided in Supplementary Table 1.

Pairs of reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts, assessed full texts of potentially relevant articles, and determined final eligibility. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion or adjudication by a third reviewer. We recorded and tabulated the reasons for full-text exclusions; the complete list is provided in Supplementary Table 2.

Two reviewers independently extracted data using a standardized, piloted form. Any inconsistencies were reconciled by consensus. When a review reported overlapping analyses across multiple publications, data were consolidated to avoid duplication.

The following variables were extracted from each review: Authors; year; country; study type (pairwise metaanalysis, network metaanalysis, or qualitative synthesis); population characteristics (donor vs recipient; adult-only or mixed; sample size; clinical context); comparisons (robotic vs laparoscopic vs open); reported outcomes by domain; databases and search window; statistical techniques (randomeffects model, fixedeffects model, methods for heterogeneity or smallstudy effects). In addition, we recorded review-reported surgical indications, patient selection criteria, and safety thresholds, as well as whether registry-derived data were incorporated into the included primary studies, to contextualize applicability and real-world relevance of the evidence.

Methodological quality of the included reviews that fulfilled the predefined eligibility criteria as systematic reviews with or without meta-analysis was assessed using AMSTAR 2[18]. Two reviewers independently applied the 16-item tool to each included review, recorded brief item-level justifications with page/figure citations, and resolved disagreements by consensus. AMSTAR 2 was applied only to studies meeting our definition of systematic reviews (with or without meta-analysis); for sources published as consensus guidelines or perspectives that contained an embedded systematic review, appraisal was restricted to the systematic-review component, and consensus/jury recommendations were not graded. Overall confidence was categorized as high, moderate, low, or critically low, anchored to performance on critical domains. Item-level checklists are provided in Supplementary Table 3.

For each outcome domain, certainty of evidence was graded using the grading of recommendations assessment, development and evaluation (GRADE) framework[19]. Judgments considered risk of bias (informed by AMSTAR 2 and the risk-of-bias methods reported within each review), inconsistency (direction and magnitude across reviews), indirectness (e.g., mixed adult/pediatric data not separable), imprecision (95%CI width and event counts), and publication bias. Certainty was summarized as high, moderate, low, or very low. Outcome-level evidence profiles (donors and recipients) summarizing effect sizes, absolute effects, and certainty judgments are provided in Supplementary Table 4.

We quantified redundancy across reviews using the corrected covered area (CCA) based on citation matrices of primary studies. CCA was interpreted using established thresholds (0%-5% slight; 6%-10% moderate; 11%-15% high; > 15% very high overlap). When overlap was substantial (≈ 10%-15% or higher), we prespecified measures to mitigate double counting by prioritizing the most recent and methodologically robust review for any pooled estimates, using overlapping reviews for contextual/narrative triangulation only. Overlap estimates were used to inform interpretation of the synthesis and, where applicable, the GRADE assessment (e.g., potential downgrading for inconsistency or publication bias when redundancy could inflate precision or repeat the same primary data). To operationalize this assessment, we constructed a study-by-review citation matrix and computed the CCA; the full matrix is provided in Supplementary Table 5.

Given the umbrella design, we did not perform de novo meta-analyses. We extracted the pooled estimates reported by each eligible review together with 95%CIs and heterogeneity metrics (I2, τ2 or Bayesian analogues), and selected the most methodologically robust estimate when multiple were available (adjusted over unadjusted models; random-effects over fixed-effects). Outcomes were organized by prespecified domains and mapped to donor (direct) vs recipient/economic (indirect) populations.

Effect-size conventions were prespecified: Mean differences (MD) for continuous outcomes (operative time, blood loss, length of stay, costs) and risk ratios (RR) for dichotomous outcomes (conversion, overall/major morbidity, readmission, 30-day mortality). Odds ratios (OR) were retained only when a source reported OR exclusively, with direction harmonized. Absolute effects per 1000 were displayed when pooled baseline risks or pooled risk differences were available; otherwise, they were labeled “not estimable”.

When clinical/methodological comparability was adequate, we reported the pooled random-effects estimate from the source review. Otherwise, we favored narrative synthesis, particularly when heterogeneity was extreme (e.g., I2 ≥ 75% or large τ2) or when conceptual heterogeneity (robotic platform generation, learning-curve stage, center volume) could not be resolved. In these situations, we reported directionality and avoided over-interpreting magnitudes. Long-term outcomes (graft and patient survival) lacked sufficient, consistent follow-up and were therefore treated narratively. All visualizations (e.g., forest-style overlays/bubble plots/heatmaps) were generated in Python 3.11 (matplotlib) using the effect sizes and uncertainty from the included reviews; no re-estimation of study-level effects was performed.

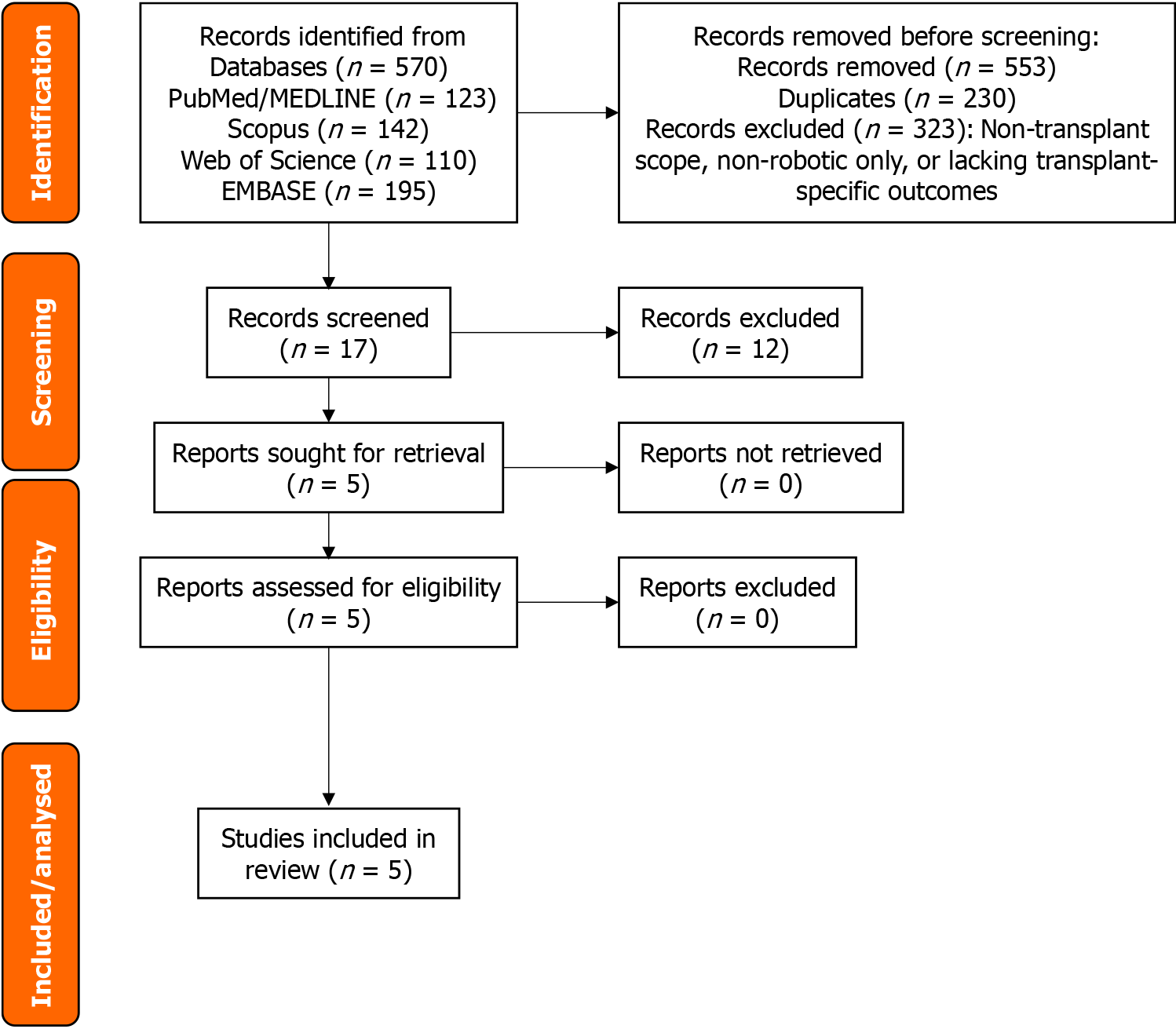

The comprehensive database search retrieved a total of 570 records. Following the removal of duplicate entries and exclusion of records deemed irrelevant after title and abstract screening (such as studies not involving liver transplantation, those evaluating only non-robotic approaches, or reviews lacking transplant-specific outcomes), 17 articles underwent full-text assessment for eligibility. Twelve were excluded for using a narrative or consensus format without systematic methodology, for the absence of comparative analysis between robotic and non-robotic techniques, or for failure to disaggregate transplant-specific data from mixed populations (Supplementary Table 2). Ultimately, the evidence base that informed this umbrella review comprised four systematic reviews, all with meta-analyses (three pairwise and one network meta-analysis), plus one consensus guideline underpinned by a registered systematic review that was used solely as contextual background and was not graded. The PRISMA 2020 flow diagram with all record numbers at each stage is presented in Figure 1.

The five included reviews were published between 2024 and 2025. One was a consensus guideline underpinned by a registered systematic review and was used only for contextual background[20]. Three were formal systematic reviews with meta-analysis[21-23], and one was a perspective article that conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis across minimally invasive organ transplantation (MIOT)[24]. Two reviews addressed living donors[21,24], and two that addressed recipient liver resections in non-transplant settings[22,23] were used as indirect evidence for transplant recipients and were explicitly downgraded for indirectness in GRADE. All the reviews compared robotic approaches with laparoscopic and/or open techniques. Three reported economic outcomes[20,23,24], of which one provided pooled cost comparisons via a network meta-analysis[23]. The review characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

| Ref. | Country | Population (scope) | Intervention | Comparator | Outcomes | Type of synthesis |

| Hobeika et al[20], 2025 | France | HPB robotic surgery (liver & pancreas); transplantrelevant questions | Robotic hepatectomy | Open, laparoscopic | Practice recommendations; clinical safety/feasibility | Consensus guideline with embedded systematic review (context only; not graded) |

| Giglio et al[21], 2025 | Italy | Living liver donors (RADH) | Robotic donor hepatectomy | Open ± laparoscopic | Clinical outcomes; surgical performance | Systematic review + meta-analysis |

| Pilz da Cunha et al[22], 2025 | Netherlands | Adults undergoing liver resection (nontransplant); used as indirect evidence for recipients | RLR | Laparoscopic (LLR) ± open | Clinical outcomes (conversion, morbidity, LOS, etc.) | Systematic review + meta-analysis |

| Koh et al[23], 2024 | Singapore | Adults undergoing liver resection (nontransplant); used as indirect evidence for recipients | Robotic (RLR) (plus LLR/OLR in network) | Network across RLR, LLR, OLR | Clinical outcomes; costs (total, procedural, hospitalization); costeffectiveness | Network meta-analysis (clinical + economic) |

| Broering et al[24], 2024 | Germany | Minimally invasive organ transplantation (multiorgan); includes liver donor/recipient subset | Robotic and laparoscopic approaches (donor/recipient) | Open and/or laparoscopic | Clinical, surgical performance, cost (pooled where available) | Systematic review + meta-analysis (perspective with embedded systematic review + meta-analysis) |

Considering living donor hepatectomy, robotic approaches were associated with lower blood loss (pooled MD: -117 mL; 95%CI: -229.5 to -5.6; I2 = 98%; τ2 = 18847.102) and a shorter hospital stay (MD: -0.60 days; 95%CI: -1.14 to -0.13; I2 = 82%; τ2 = 0.259), although at the expense of a longer operative time (MD: +105 minutes; 95%CI: +68.5 to +142.2; I² = 91%; τ² = 1772.424)[21]. These results, summarized in Table 2 (donors, direct), are derived from transplant-specific evidence and the donor-focused meta-analysis[21], and they are also supported in directionality by the broader MIOT review[24]. With respect to donor complications, only ratio measures were reported in the source reviews. Therefore, absolute risks per 1000 could not be estimated and are flagged accordingly in Table 2 as not estimable under GRADE.

| Outcome | Assumed risk (comparator per 1000) | Corresponding risk (robotic per 1000) | Effect [RR/OR/MD (95%CI)] | Number of studies (participants) | Certainty (GRADE) | Notes |

| Overall complications | Not estimable (baseline risk not reported) | Not estimable (requires baseline or pooled RD) | RR = 0.85 (0.72-0.99) | 6 studies; 2168 donors | Low | 1,2,4 |

| Major complications (Clavien-Dindo ≥ III) | Not estimable (baseline risk not reported) | Not estimable (requires baseline or pooled RD) | RR = 0.80 (0.65-0.98) | 6 studies; 2168 donors | Low | 1,2,4 |

| Minor complications (Clavien-Dindo I) | Not estimable (baseline risk not reported) | Not estimable (requires baseline or pooled RD) | OR = 5.14 (1.06-24.93) (open vs robotic) | 2 studies; 216 donors | Low | 1,3,4 |

| Operative time (minutes) | N/A (continuous outcome) | N/A (continuous outcome) | MD = +105 (68142) minutes | 6 studies; 2168 donors | Low | 1,2 |

| Blood loss (mL) | N/A (continuous outcome) | N/A (continuous outcome) | MD = -117 (-229 to | 6 studies; 2168 donors | Low | 1,2 |

| Length of stay (days) | N/A (continuous outcome) | N/A (continuous outcome) | MD = -0.60 (-1.14 to -0.10) days | 6 studies; 2168 donors | Low | 1,2 |

In contrast, when examining recipient liver resections, the available evidence comes from non-transplant settings and is therefore indirect. As shown in Table 3 and using data from Pilz da Cunha et al[22], robotic resections were associated with fewer conversions to open procedures (-50 per 1000; RR = 0.41; 95%CI: 0.32-0.52; I2 not reported; τ2 not reported; number needed to treat ≈ 20), lower severe morbidity (-10 per 1000; RR = 0.81; 95%CI: 0.70-0.94; I2 = 7%; τ2 not reported), and a trend toward reduced overall morbidity (-20 per 1000; RR = 0.92; 95%CI: 0.84-1.00; I2 = 24%; τ2 not reported), while 30-day mortality showed no significant difference (RR = 0.97; 95%CI: 0.68-1.37; I² = 0%; τ² not reported). Differences in length of stay (MD: -0.27 days; I² = 41%; τ² not reported) and operative time (MD: +8.8 minutes; I² = 90%; τ² not reported) were small and heterogeneous. In GRADE, all these outcomes are explicitly downgraded for indirectness.

| Outcome | Assumed risk (comparator per 1000) | Corresponding risk (robotic per 1000) | Effect, RR/MD; RD when available (95%CI) | Number of studies (participants) | Certainty (GRADE) | Notes |

| Conversion to open | RD pooled (no baseline required) | -50 per 1000 | RR = 0.41 (0.32-0.52); RD = -0.05 ( | 24 studies; participants NR | Low-moderate | 1,3 |

| Overall morbidity (any) | RD pooled (no baseline required) | -20 per 1000 | RR = 0.92 (0.84-1.00); RD = -0.02 ( | 20 studies; participants NR | Low | 1,4 |

| Severe morbidity (Clavien-Dindo ≥ III) | RD pooled (no baseline required) | -10 per 1000 | RR = 0.81 (0.70, 0.94); RD ≈ -0.01 | 21 studies; participants NR | Low-moderate | 1,3 |

| Readmission | RD pooled (no baseline required) | +10 per 1000 | RR = 1.24 (1.09, 1.41); RD = +0.01 (0.00, 0.01) | 20 studies; participants NR | Low | 1,2 |

| 30day mortality | Not estimable | Not estimable | RR = 0.77 (0.51, 1.15) | 20 studies; participants NR | Low | 1,4,5 |

| Operative time (minutes) | N/A | N/A | MD = +8.8 (-4.8, 22) minutes | 23 studies; participants NR | Low | 1,2 |

| Length of stay (days) | N/A | N/A | MD = -0.27 (-0.67, 0.12) days | 26 studies; participants NR | Low | 1,2 |

Regarding the economic evidence, which also originates from non-transplant resections, the network meta-analysis by Koh et al[23] indicated that both robotic liver resection (RLR) and laparoscopic resections (LLR) reduced total costs compared to open surgery (OLR), with MD: -$217.48 for LLR vs OLR, and MD: -$243.82 for RLR vs OLR, whereas RLR incurred higher procedural costs than LLR (MD: +$2310.17) but lower hospitalization costs than OLR (MD: -$3527.20). These findings, detailed in Table 4, are considered hypothesis-generating for transplant contexts and were downgraded for indirectness in GRADE.

| Economic outcome | Contrast | Effect, MD (95%CI/CrI) | Source | Certainty (GRADE) | Notes |

| Total costs | RLR vs OLR | -243.82 (-326.46 to -162.78) | Network meta-analysis (Koh et al[23], 2024) | Low-moderate | 1,2 |

| Total costs | LLR vs OLR | -217.48 (-282.44 to -154.94) | Network meta-analysis (Koh et al[23], 2024) | Low-moderate | 1,2 |

| Procedure costs | RLR vs LLR | +2310.17 (+812.98 to +3808.74) | Network meta-analysis (Koh et al[23], 2024) | Low-moderate | 1,2 |

| Hospitalization costs | RLR vs OLR | -3527.20 (-5760.20 to | Network meta-analysis (Koh et al[23], 2024) | Low-moderate | 1,2 |

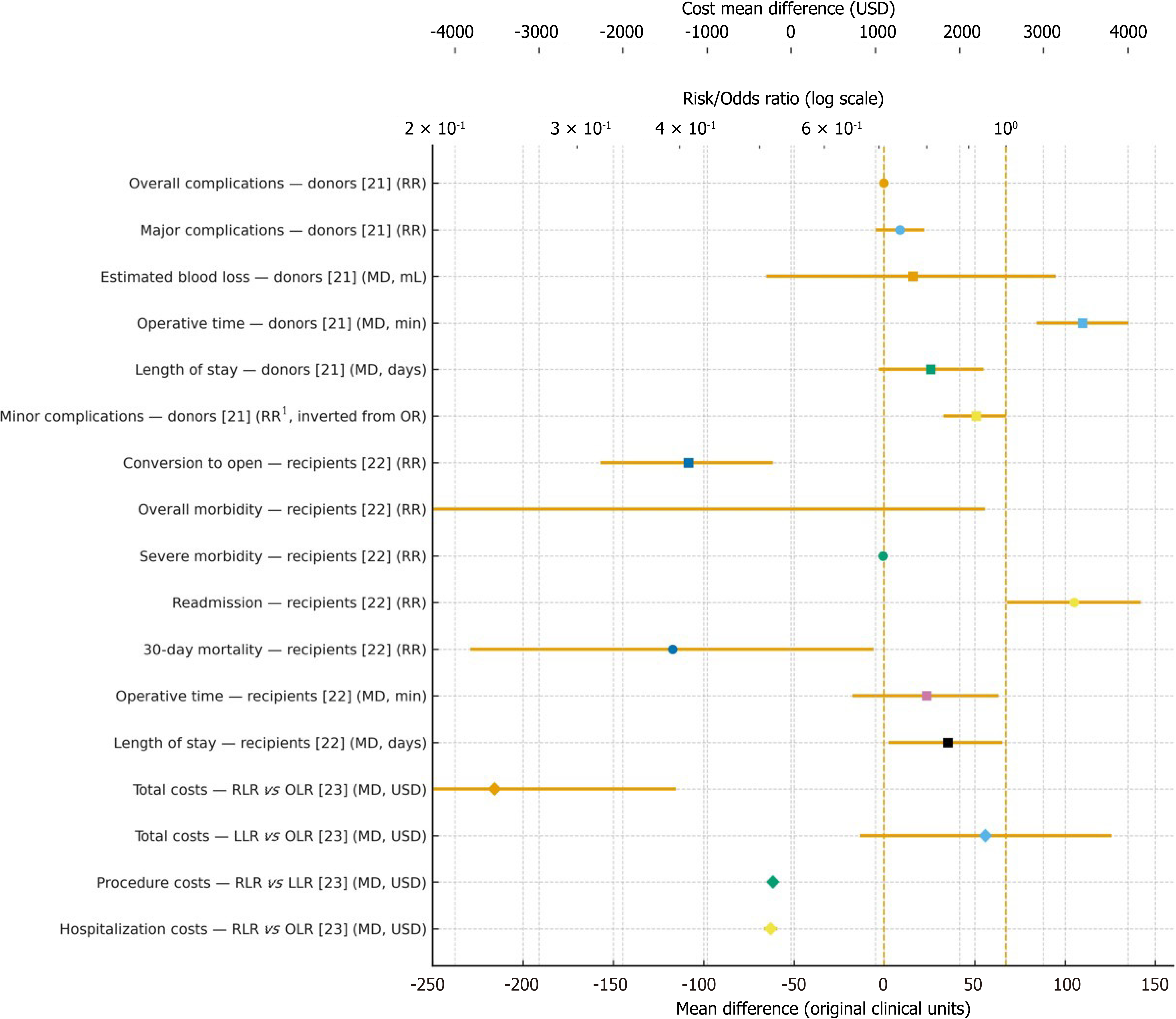

Taken together, these donor, recipient, and economic contrasts are synthesized visually in Figure 2, which aligns with the results of Tables 2, 3, and 4. This figure displays intra-operative outcomes (operative time, blood loss, conversion to open) and post-operative outcomes (morbidity, readmission, mortality, length of stay), with mean differences shown on the lower X-axis and risk ratios on the upper log-scale axis, while economic contrasts are presented as cost mean differences in United State dollar on a separate top axis. Directionality is consistent across outcomes, where leftward estimates favor robotic surgery. For donor complications, absolute risks per 1000 are not estimable, whereas for recipients these values are provided where available in Tables 3 and 4. Importantly, the “minor complications” contrast was originally reported as open vs robotic but has been inverted here to maintain the uniform convention of “leftward favors robotic”.

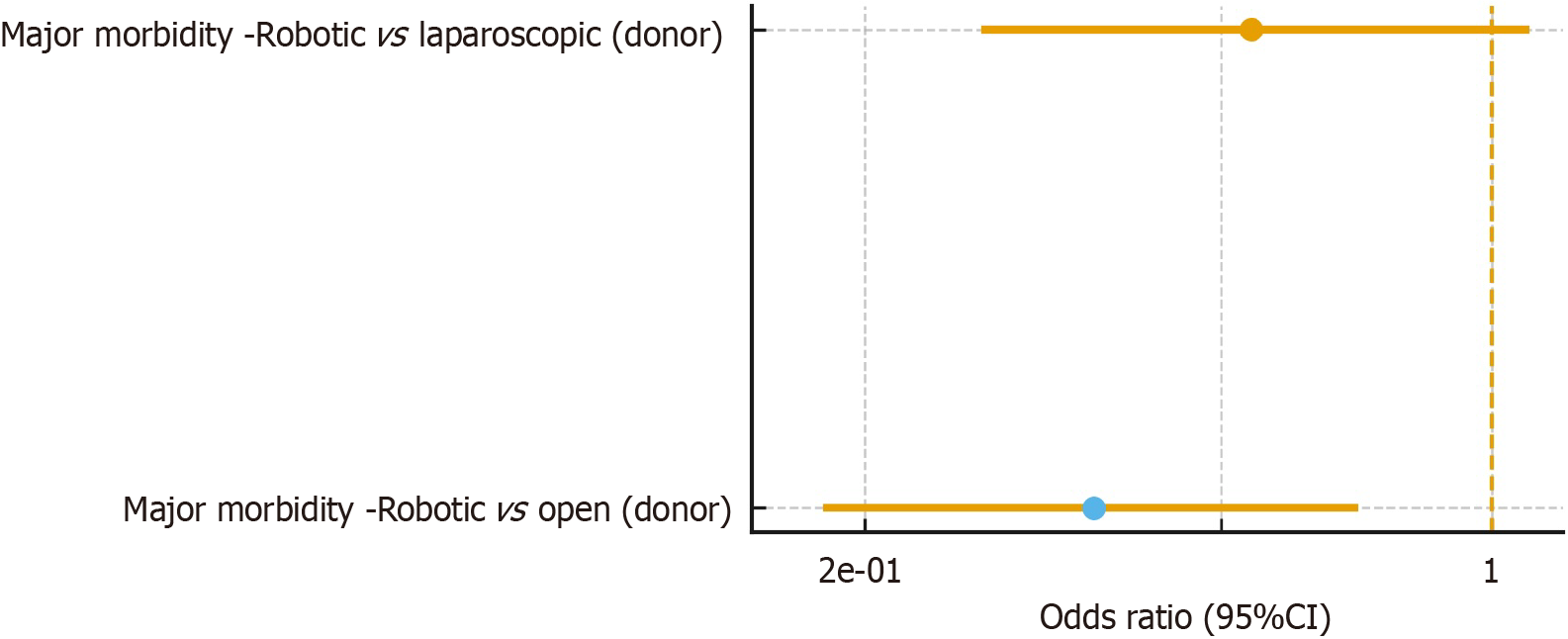

Finally, Figure 3 presents the contextual overlay from Broering et al[24], which aggregates transplant and non-transplant evidence through a MIOT meta-analysis. Liver-related contrasts are shown to illustrate consistency with the transplant-focused syntheses but are not included in Figure 2 and are not considered in AMSTAR 2 or GRADE ratings to avoid double counting and excessive indirectness. The consensus guideline with an embedded PROSPERO-registered systematic review[20] also informs the broader interpretation of these findings but, similarly, was not graded quantitatively. None of the included systematic reviews performed stratified analyses by robotic platform generation, learning-curve stage, or institutional case volume. Therefore, sensitivity analyses on these factors could not be examined within this umbrella review.

Economic findings derived from non-transplant liver resections are summarized in Table 4. Accordingly, certainty was downgraded for indirectness in GRADE. The network meta-analysis by Koh et al[23] showed higher procedure costs for RLR vs LLR (MD: +$2310; 95%CI: +$813 to +$3809), alongside lower total costs for RLR vs OLR (MD: -$244; 95%CI: -$326 to -$163) and LLR vs OLR (MD: -$217; 95%CI: -$282 to -$155), and lower hospitalization costs for RLR vs OLR (MD:

The study-by-review citation matrix is provided in Supplementary Table 5. Across the graded corpus (Giglio et al[21] for donors; Pilz da Cunha et al[22] for recipients; Koh et al[23] for economics), the primary study sets were disjoint, yielding CCA = 0.0% (n = 101 occurrences; r = 101 unique studies; c = 3). When Broering et al[24] (MIOT) is included to reflect the broader contextual evidence, the overall CCA was 1.25%, which falls into the slight overlap range (0%-5%).

Given the extreme heterogeneity in some pooled outcomes, including donor blood loss (I² = 98%) and operative time (I² = 91%) from Giglio et al[21] and recipient operative time (I² = 90%) from Pilz da Cunha et al[22], we applied a pre-specified rule and emphasized narrative synthesis for these endpoints to avoid magnitude over-interpretation. Long-term graft and patient survival remained non-poolable due to sparse, short-horizon data.

The consensus-based systematic review by Hobeika et al[20] provided contextual guidance on feasibility, learning-curve dynamics, and implementation frameworks for robotic donor hepatectomy. It highlighted the importance of structured training pathways, gradual adoption strategies, and institutional support to optimize donor safety and procedural success.

Robotic approaches show small but consistent perioperative advantages over conventional techniques. In comparative liver resections (indirect), RLR reduces overall morbidity (RR: 0.92; 95%CI: 0.84-1.00) and severe morbidity (RR: 0.81; 95%CI: 0.70-0.94) vs LLR[22], with broadly similar blood loss, length of stay, and 30-day mortality, while conversion to open intervention is less frequent (RR ≈ 0.41)[22]. In living donors (direct), pure minimally invasive techniques (pure laparoscopic donor hepatectomy and robot-assisted donor hepatectomy) shorten length of stay (MD ≈ -0.60 days) and reduce blood loss at the expense of longer operative time[21], and minor complications tend to be fewer[21]. Cost-wise (indirect), a network meta-analysis finds LLR the least expensive overall, with RLR incurring higher procedural but lower hospitalization costs (e.g., LLR vs RLR -$3363; 95%CI: -$5629 to -$1119)[23]. Major complications, readmission, and early mortality are broadly comparable across the approaches[21,22].

Importantly, transplant-specific graft outcomes remain underreported, and long-term graft and patient survival lack sufficient data for pooled inference. These gaps were consistently acknowledged across reviews, including Broering et al[24], whose MIOT meta-analysis provided additional transplant-relevant contrasts but could not address long-term outcomes.

Across the included reviews, AMSTAR 2 appraisal showed overall confidence ranging from moderate to high: Pilz da Cunha et al[22], Koh et al[23], and Broering et al[24] were rated high, whereas Giglio et al[21] and Hobeika et al[20] were rated moderate. Strengths common to the higher-quality reviews included comprehensive multi-database searches, duplicate screening/extraction, and appropriate random-effects or network meta-analytic approaches. Their limitations chiefly involved incomplete reporting of grey literature and occasional protocol or registration gaps. The consolidated summary of AMSTAR 2 ratings is presented in Table 5 and item-level checklists are available in Supplementary Table 3.

| Ref. | Overall AMSTAR 2 rating | Key strengths/Limitations |

| Hobeika et al[20] | Moderate | PROSPERO-registered SR; multi-database search; dual/blinded quality appraisal; no de novo quantitative pooling for transplant-specific outcomes |

| Giglio et al[21] | Moderate | Protocol/registration; duplicate screening and extraction; sensitivity analyses; limited grey literature reporting |

| Pilz da Cunha et al[22] | High | Comprehensive search; duplicate processes; risk-of-bias assessment; appropriate meta-analytic methods; sensitivity/subgroup analyses |

| Koh et al[23] | High | Transparent network meta-analysis; study quality and model diagnostics described; heterogeneity and small-study effects assessed |

| Broering et al[24] | High | Explicit multi-database search with PRISMA flow; pooled estimates with heterogeneity; consideration of study quality; publication-bias assessment where feasible |

Certainty assessments followed GRADE at the outcome level are synthesized in Tables 6, 7, and 8. For living donors (direct evidence), robotic techniques conferred reductions in blood loss and length of stay but required longer operative time. Certainty for these continuous outcomes is generally low because the underlying studies are observational and exhibit substantial heterogeneity. Absolute risks for donor complications were not estimable as they were based on ratio measures without pooled baselines. For recipients (indirect evidence from non-transplant resections), robotic approaches conferred reduced conversion to open intervention and reduced severe morbidity with low-to-moderate certainty, while overall interpretations are limited by indirectness, occasional imprecision, and heterogeneity for some endpoints (e.g., operative time). Economic contrasts are likewise indirect with certainty graded low-to-moderate, reflecting a risk of bias in observational inputs, heterogeneity in cost baskets and price-year handling, and indirectness in transplant contexts. Outcome-level evidence profiles that underpin these judgments are provided in Supplementary Table 4 and are cross-referenced from Table 6.

| Outcome | Assumed risk (comparator per 1000) | Corresponding risk (robotic per 1000) | Effect [RR/MD (95%CI)] | No. of studies (participants) | Certainty (GRADE) | Comments/footnotes |

| Operative time (minutes) | N/A (continuous outcome) | N/A (continuous outcome) | MD = +105 (68142) | 6 studies; 2168 donors | Low | Robotic longer operative time; source Giglio et al[21], 2025 (ODH vs RADH section) |

| Blood loss (mL) | N/A (continuous outcome) | N/A (continuous outcome) | MD = -117 | 6 studies; 2168 donors | Low | Robotic less blood loss; Giglio et al[21], 2025 |

| Length of stay (days) | N/A (continuous outcome) | N/A (continuous outcome) | MD = -0.60 (-1.14 to | 6 studies; 2168 donors | Low | Robotic shorter LOS; Giglio et al[21], 2025 |

| Minor complications (Clavien-Dindo I) | Not estimable (baseline risk not reported) | Not estimable (requires baseline or pooled RD) | OR = 5.14 (1.06-24.93) | 2 studies; 216 donors | Low | OR 5.14 (1.06-24.93) (open vs robotic). Baseline not reported; absolute effect not estimable |

| Outcome | Assumed risk (comparator per 1000) | Corresponding risk (robotic per 1000) | Effect [RR/MD (95%CI)] | Number of studies (participants) | Certainty (GRADE) | Comments/footnotes |

| Conversion to open | RD pooled (no baseline required) | -50 per 1000 | RR 0.41 (0.32-0.52); RD -0.05 | 24 studies; participants NR | Low-moderate | Pilz da Cunha et al[22], 2025; NNT = 20 |

| Overall morbidity (any complication) | RD pooled (no baseline required) | -20 per 1000 | RR 0.92 (0.84-1.00); RD -0.02 | 20 studies; participants NR | Low | Pilz da Cunha et al[22], 2025 (overall morbidity section) |

| Severe morbidity (Clavien-Dindo ≥ III) | RD pooled (no baseline required) | -10 per 1000 | RR 0.81 (0.70, 0.94); RD ≈ -0.01 (NNT = 100) | 21 studies; participants NR | Low-moderate | Pilz da Cunha et al[22], 2025; NNT = 100 overall; subgroup major RD -0.03 |

| R0 resection rate | Not estimable (RD not provided) | Not estimable | RR 1.02 (1.01-1.03) | NR (multi-study) | Low | Pilz da Cunha et al[22], 2025 (counts not explicit in text extraction) |

| Readmission | RD pooled (no baseline required) | +10 per 1000 | RR 1.24 (1.09-1.41); RD +0.01 (0.00-0.01) | 20 studies; participants NR | Low | Pilz da Cunha et al[22], 2025 |

| Length of stay (days) | N/A (continuous outcome) | N/A (continuous outcome) | MD -0.27 (-0.67 to 0.12) | 26 studies; participants NR | Low | Pilz da Cunha et al[22], 2025 |

| 30-day or in-hospital mortality | Not estimable (RD not provided) | Not estimable (requires baseline risk) | RR 0.77 (0.51-1.15) | 20 studies; participants NR | Low | Pilz da Cunha et al[22], 2025 (30-day mortality) |

| Blood loss (mL) | N/A (continuous outcome) | N/A (continuous outcome) | No significant difference (overall) | NR | Low | Pilz da Cunha et al[22], 2025 (overall non-significant; subgroup differences exist) |

| Operative time (minutes) | N/A (continuous outcome) | N/A (continuous outcome) | MD +8.8 (-4.8 to 22) | 23 studies; participants NR | Low | Pilz da Cunha et al[22], 2025; high heterogeneity (I2 ≈ 90%) |

| Outcome | Effect estimate (MD/OR/NMA contrast) | Certainty (GRADE) | Comments/footnotes |

| Total costs | RLR vs OLR: MD -243.82 (-326.46 to -162.78) | Low-moderate | Less intraoperative blood loss with RLR vs OLR also reported |

| Total costs (LLR vs OLR) | MD -217.48 (-282.44 to -154.94) | Low-moderate | Koh et al[23], 2024 network meta-analysis |

| Procedure costs | RLR vs LLR: MD + 2310.17 (+812.98 to +3808.74) | Low-moderate | Downgrades: RoB (observational inputs); indirectness to transplant setting; currency/modeling heterogeneity1,2 |

| Hospitalization costs | RLR vs OLR: MD -3527.20 (-5760.20 to -1367.50) | Low-moderate | Lower hospitalization costs for RLR vs OLR |

| Transfusion | RLR vs OLR: OR 0.34 (0.17-0.66) | Low-moderate | Koh et al[23], 2024 NMA |

| Overall morbidity | RLR vs OLR: OR 0.41 (0.26-0.59) | Low-moderate | Lower morbidity vs OLR |

This umbrella review synthesized and critically appraised the current evidence on robotic-assisted donor and recipient hepatectomy within liver transplantation. In living donors (direct evidence), robotics is associated with lower intraoperative blood loss and shorter length of stay, at the cost of longer operative time. In recipients (indirect evidence from non-transplant resections), robotics shows lower conversion to open surgery and reduced severe morbidity, with no difference in 30-day mortality. Economic findings are context-dependent: Laparoscopy is generally least costly overall, while robotics tends to have higher procedure-level but lower hospitalization costs than open surgery.

Across the included meta-analyses and systematic reviews, reductions in conversion to open surgery and in severe morbidity were observed in recipients (indirect evidence drawn from non-transplant hepatic resections), a pattern consistent with reports in complex hepatobiliary resections where robotic assistance has been associated with reproducibly low conversion and major-complication rates[25,26]. In donors, our synthesis indicates lower intraoperative blood loss and shorter hospital stay, offset by longer operative time; comparative donor hepatectomy series similarly emphasize this trade-off, particularly during early adoption phases[27]. While donor safety has also been favorable in other living-donor robotic procedures (e.g., robotic donor nephrectomy), these data mainly indicate feasibility in healthy donors and should be regarded as contextual rather than confirmatory for liver donation[25]. Because baseline event counts were inconsistently reported in the source reviews, absolute risks for donor complications could not be estimated; therefore, these safety signals should be interpreted cautiously.

Some source reviews reported ancillary perioperative or oncologic endpoints - such as margin status and transfusion requirements - in selected non-transplant hepatic resections[22]. However, these outcomes were not part of our predefined core endpoints and were inconsistently defined and sparsely reported across studies, precluding a structured synthesis. We therefore emphasize the donor-focused perioperative profile (lower blood loss and shorter hospital stay at the expense of longer operative time) and the recipient-oriented signals from indirect evidence (lower conversion and severe morbidity with no early-mortality difference), rather than extrapolating from heterogeneous ancillary outcomes.

Economic analyses reveal a nuanced but internally consistent pattern derived from non-transplant hepatic resections (indirect evidence). Laparoscopic liver resection emerges as the least costly overall strategy, while robotic assistance tends to incur higher procedure-level costs than laparoscopy but offers lower hospitalization costs than open surgery, with total costs that vary by context[23]. Comparative syntheses further suggest that when capital expenditure is excluded, robotic and laparoscopic approaches can approach cost equivalence, whereas reductions in intensive care unit stay and morbidity may render robotic resections comparable to open surgery in overall costs in selected settings[15,14]. Taken together, these findings underscore that cost performance is highly center-dependent - volume, platform maturity, and workflow optimization likely modulate whether robotic programs achieve parity or advantage.

Study overlap across the included reviews was slight by citation-matrix assessment, with a CCA of approximately 0.0% in the qualified corpus and approximately 1.25% when the broader MIOT context was considered, indicating a low risk of double counting. Even so, a few high-volume centers appeared repeatedly and may subtly influence pooled estimates through center-level clustering. Consistent with consensus cautions by Hobeika et al[20], future syntheses should report citation-matrix metrics and adjust for potential overlap (and center effects) to refine effect estimates and generalizability.

Qualitative evidence consistently highlights ergonomic and visualization advantages of robotic platforms that may support more precise vascular and biliary dissection and facilitate meticulous parenchymal transection[14,22,28]. The ROBOT4HPB consensus (the Paris jury-based consensus on robotic HPB surgery) similarly endorses feasibility across most HPB procedures while emphasizing credentialing, structured training, and prospective registries to ensure safety and reproducibility[20]. In our umbrella review, these qualitative mechanisms offer a plausible explanation for the perioperative signals we observed - namely, lower blood loss and shorter length of stay in donors (with longer operative time), and lower conversion and severe morbidity in recipients (indirect evidence) - without introducing additional endpoints beyond our predefined core set. Donor-reported outcomes such as body image or quality of life have been described in source narratives, but they were heterogeneous and not part of our core endpoints; accordingly, we regard them as contextual rather than confirmatory for this synthesis[11,21].

The methodological quality of the included reviews was generally moderate to high by AMSTAR 2; however, the certainty of evidence for key endpoints was frequently downgraded. Heterogeneity was substantial for several continuous outcomes (e.g., blood loss and operative time), indirectness applied to recipient outcomes and to all economic analyses (derived from non-transplant hepatic resections), and imprecision/incomplete reporting limited the expression of donor complications as absolute risks. These constraints mirror the scarcity of randomized data highlighted by Pilz da Cunha et al[22] and the inconsistent reporting of cost components noted by Koh et al[23]. Consistent with the ROBOT4HPB consensus, standardization of outcome definitions and reporting frameworks is needed to enable more robust comparisons and clearer grading of certainty across domains[20].

A major strength of this umbrella review is its integrated framing across clinical, economic, and methodological domains, yielding a coherent map of benefits and trade-offs for robot-assisted hepatectomy in transplantation. We triangulate perioperative clinical endpoints - direct evidence in donors and indirect signals in recipients - with economic data from non-transplant hepatic resections and a structured methodological appraisal (AMSTAR 2 plus citation-matrix assessment showing slight overlap). By pre-specifying a core endpoint set and avoiding over-interpretation of heterogeneous ancillary outcomes, the synthesis preserves internal consistency and transparency while broadening the interpretability of cost patterns beyond the transplant setting.

Nevertheless, several limitations apply. Continuous outcomes such as blood loss and operative time exhibited substantial heterogeneity; recipient outcomes and all economic comparisons rely on indirect evidence from non-transplant resections; and incomplete baseline reporting in source reviews prevented expressing donor complications as absolute risks. An additional limitation is that model selection (e.g., robotic platform generation), surgeon learning-curve effects, and center-volume impacts were not examined through sensitivity analyses in the source reviews, and thus could not be assessed in this umbrella review. These factors are likely to influence perioperative outcomes and should be explored in future primary studies and meta-analyses. Finally, several endpoints showed extreme heterogeneity or unresolved conceptual variability (e.g., platform generation, learning-curve stage, center volume), for which we favored narrative synthesis rather than pooled inference, and long-term graft and patient survival could not be meta-analyzed due to insufficient and short-horizon data, remaining priorities for prospective registries and stratified meta-analyses.

The perioperative profile demonstrated for robotic donor hepatectomy - lower intraoperative blood loss and shorter hospital stay, offset by longer operative time - supports selective adoption in experienced, high-volume centers with structured training and credentialing pathways[20]. For recipients, signals derived from indirect evidence (non-transplant hepatic resections) suggest lower conversion to open surgery and reduced severe morbidity in selected anatomically complex cases; however, transplant-specific data remain limited, and programmatic adoption should proceed within prospective protocols and registries. From an economic standpoint, laparoscopic liver resection is generally the least costly overall, while robotic assistance tends to incur higher procedure-level costs than laparoscopy but lower hospitalization costs than open surgery, making operative efficiency, volume consolidation, and financing models that amortize capital expenditure central to implementation strategies[23].

Future studies should prioritize randomized or well-designed prospective comparative trials, particularly in recipient populations, with standardized endpoint definitions and stratification by platform generation, learning-curve stage, and center volume. Economic evaluations must adopt harmonized cost frameworks (direct and indirect costs), report price-year adjustments, and assess cost-utility over long-term follow-up. The establishment of international registries will be crucial to harmonize data, reduce bias, and enable robust learning-curve analyses[20,29,30]. Finally, donor- and recipient-reported outcomes (e.g., quality of life, recovery experience) should be integrated to ensure that patient-centered metrics inform surgical innovation and programmatic adoption.

Robotic-assisted approaches in living donor hepatectomy are associated with lower intraoperative blood loss and shorter hospital stay, at the cost of longer operative time; major safety outcomes appear broadly comparable to conventional techniques. Given substantial heterogeneity for some endpoints, these findings should be interpreted within structured programs and with attention to case mix and implementation factors.

For recipients, the current evidence is best viewed as an evidence deficiency: Available estimates derive from non-transplant resections (indirect evidence) and are underpowered for long-term graft and patient survival, so transplant-specific comparative effectiveness remains uncertain and firm clinical recommendations cannot yet be made.

Economic contrasts are also indirect; network analyses suggest laparoscopic resection is least expensive overall, while robotic resection incurs higher procedural but lower hospitalization costs vs open surgery, yet heterogeneous cost baskets and price-year handling preclude definitive pooled cost-effectiveness and render these results hypothesis-generating for transplant contexts. To enable robust future comparisons in recipients, studies should adopt a predetermined minimum dataset and uniform outcome definitions that include standardized case-mix, procedural variables, complications using accepted criteria, follow-up endpoints, learning-curve and center-volume strata, and transparent economic reporting. Prospective registries and/or randomized comparisons adhering to these standards are needed to provide transplant-specific, audit-ready evidence.

| 1. | Barrera-Lozano LM, Ramírez-Arbeláez JA, Muñoz CL, Becerra JA, Toro LG, Ardila CM. Portal Vein Thrombosis in Liver Transplantation: A Retrospective Cohort Study. J Clin Med. 2023;12:3951. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ardila CM, González-Arroyave D, Ramírez-Arbeláez J. Letter to the Editor: Refining Predictive Models for Early Extrahepatic Recurrence in Colorectal Liver Metastases: Opportunities Beyond Machine Learning. World J Surg. 2025;49:1377-1378. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Lincango Naranjo EP, Garces-Delgado E, Siepmann T, Mirow L, Solis-Pazmino P, Alexander-Leon H, Restrepo-Rodas G, Mancero-Montalvo R, Ponce CJ, Cadena-Semanate R, Vargas-Cordova R, Herrera-Cevallos G, Vallejo S, Liu-Sanchez C, Prokop LJ, Ziogas IA, Vailas MG, Guerron AD, Visser BC, Ponce OJ, Barbas AS, Moris D. Robotic Living Donor Right Hepatectomy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Clin Med. 2022;11:2603. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Rho SY, Lee JG, Joo DJ, Kim MS, Kim SI, Han DH, Choi JS, Choi GH. Outcomes of Robotic Living Donor Right Hepatectomy From 52 Consecutive Cases: Comparison With Open and Laparoscopy-assisted Donor Hepatectomy. Ann Surg. 2022;275:e433-e442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 8.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Schulze M, Elsheikh Y, Boehnert MU, Alnemary Y, Alabbad S, Broering DC. Robotic surgery and liver transplantation: A single-center experience of 501 robotic donor hepatectomies. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2022;21:334-339. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Chen PD, Wu CY, Hu RH, Ho CM, Lee PH, Lai HS, Lin MT, Wu YM. Robotic liver donor right hepatectomy: A pure, minimally invasive approach. Liver Transpl. 2016;22:1509-1518. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 105] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Cheah YL, Yang HY, Simon CJ, Akoad ME, Connor AA, Daskalaki D, Han DH, Brombosz EW, Kim JK, Tellier MA, Ghobrial RM, Gaber AO, Choi GH. The learning curve for robotic living donor right hepatectomy: Analysis of outcomes in 2 specialized centers. Liver Transpl. 2025;31:190-200. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sambommatsu Y, Kumaran V, Imai D, Savsani K, Khan AA, Sharma A, Saeed M, Cotterell AH, Levy MF, Lee SD, Bruno DA. Early outcomes of robotic vs open living donor right hepatectomy in a US Center. Surg Endosc. 2025;39:1643-1652. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Raptis DA, Elsheikh Y, Alnemary Y, Marquez KAH, Bzeizi K, Alghamdi S, Alabbad S, Alqahtani SA, Troisi RI, Boehnert MU, Malago M, Wu YM, Broering DC; OTCE KFSHRC Collaborative (Appendix). Robotic living donor hepatectomy is associated with superior outcomes for both the donor and the recipient compared with laparoscopic or open - A single-center prospective registry study of 3448 cases. Am J Transplant. 2024;24:2080-2091. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 15.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Iyengar A, McCulloch MI. Paediatric kidney transplantation in under-resourced regions-a panoramic view. Pediatr Nephrol. 2022;37:745-755. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Domínguez-Gil B, Ascher NL, Fadhil RAS, Muller E, Cantarovich M, Ahn C, Berenguer M, Bušić M, Egawa H, Gondolesi GE, Haberal M, Harris D, Hirose R, Ilbawi A, Jha V, López-Fraga M, Andrés Madera S, Najafizadeh K, O'Connell PJ, Rahmel A, Shaheen FAM, Twahir A, Van Assche K, Wang H, Haraldsson B, Chatzixiros E, Delmonico FL. The Reality of Inadequate Patient Care and the Need for a Global Action Framework in Organ Donation and Transplantation. Transplantation. 2022;106:2111-2117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Yeow M, Soh S, Starkey G, Perini MV, Koh YX, Tan EK, Chan CY, Raj P, Goh BKP, Kabir T. A systematic review and network meta-analysis of outcomes after open, mini-laparotomy, hybrid, totally laparoscopic, and robotic living donor right hepatectomy. Surgery. 2022;172:741-750. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Birgin E, Heibel M, Hetjens S, Rasbach E, Reissfelder C, Téoule P, Rahbari NN. Robotic versus laparoscopic hepatectomy for liver malignancies (ROC'N'ROLL): a single-centre, randomised, controlled, single-blinded clinical trial. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2024;43:100972. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Daskalaki D, Gonzalez-Heredia R, Brown M, Bianco FM, Tzvetanov I, Davis M, Kim J, Benedetti E, Giulianotti PC. Financial Impact of the Robotic Approach in Liver Surgery: A Comparative Study of Clinical Outcomes and Costs Between the Robotic and Open Technique in a Single Institution. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2017;27:375-382. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 9.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Pilz da Cunha G, Coupé VMH, Zonderhuis BM, Bonjer HJ, Erdmann JI, Kazemier G, Besselink MG, Swijnenburg RJ. Healthcare cost expenditure for robotic versus laparoscopic liver resection: a bottom-up economic evaluation. HPB (Oxford). 2024;26:971-980. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Page MJ, McKenzie JE, Bossuyt PM, Boutron I, Hoffmann TC, Mulrow CD, Shamseer L, Tetzlaff JM, Akl EA, Brennan SE, Chou R, Glanville J, Grimshaw JM, Hróbjartsson A, Lalu MM, Li T, Loder EW, Mayo-Wilson E, McDonald S, McGuinness LA, Stewart LA, Thomas J, Tricco AC, Welch VA, Whiting P, Moher D. The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ. 2021;372:n71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44932] [Cited by in RCA: 51475] [Article Influence: 10295.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 17. | Bossuyt PM, Deeks JJ, Leeflang MM, Takwoingi Y, Flemyng E. Evaluating medical tests: introducing the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Diagnostic Test Accuracy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2023;7:ED000163. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 39.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells G, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, Moher D, Tugwell P, Welch V, Kristjansson E, Henry DA. AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ. 2017;358:j4008. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3100] [Cited by in RCA: 6500] [Article Influence: 722.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Atkins D, Brozek J, Vist G, Alderson P, Glasziou P, Falck-Ytter Y, Schünemann HJ. GRADE guidelines: 2. Framing the question and deciding on important outcomes. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:395-400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1094] [Cited by in RCA: 1488] [Article Influence: 99.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Hobeika C, Pfister M, Geller D, Tsung A, Chan AC, Troisi RI, Rela M, Di Benedetto F, Sucandy I, Nagakawa Y, Walsh RM, Kooby D, Barkun J, Soubrane O, Clavien PA; ROBOT4HPB consensus group. Recommendations on Robotic Hepato-Pancreato-Biliary Surgery. The Paris Jury-Based Consensus Conference. Ann Surg. 2025;281:136-153. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 26.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Giglio MC, Rompianesi G, Benassai G, Filardi G, Lo Bianco EM, Montalti R, Troisi RI. Minimally Invasive Donor Hepatectomy in Living Donor Liver Transplantation-Evidence of Benefit?: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Current Literature. Transplantation. 2025;109:1581-1590. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Pilz da Cunha G, Hoogteijling TJ, Besselink MG, Alzoubi MN, Swijnenburg RJ, Abu Hilal M. Robotic versus laparoscopic liver resection: a systematic review and meta-analysis of comparative studies. Int J Surg. 2025;111:5549-5571. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Koh YX, Zhao Y, Tan IE, Tan HL, Chua DW, Loh WL, Tan EK, Teo JY, Au MKH, Goh BKP. Comparative cost-effectiveness of open, laparoscopic, and robotic liver resection: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Surgery. 2024;176:11-23. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Broering DC, Raptis DA, Malago M, Clavien PA; MIOT Collaborative. Revolutionizing Organ Transplantation With Robotic Surgery. Ann Surg. 2024;280:706-712. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Brunotte M, Rademacher S, Weber J, Sucher E, Lederer A, Hau HM, Stolzenburg JU, Seehofer D, Sucher R. Robotic assisted nephrectomy for living kidney donation (RANLD) with use of multiple locking clips or ligatures for renal vascular closure. Ann Transl Med. 2020;8:305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Patil A, Ganpule A, Singh A, Agrawal A, Patel P, Shete N, Sabnis R, Desai M. Robot-assisted versus conventional open kidney transplantation: a propensity matched comparison with median follow-up of 5 years. Am J Clin Exp Urol. 2023;11:168-176. [PubMed] |

| 27. | Di Pangrazio M, Pinto F, Martinino A, Toti F, Pozza G, Giovinazzo F. Robotic Surgical Techniques in Transplantation: A Comprehensive Review. Transplantology. 2024;5:72-84. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 28. | Robot-Assisted Surgery Compared with Open Surgery and Laparoscopic Surgery: Clinical Effectiveness and Economic Analyses [Internet]. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health; 2011 . [PubMed] |

| 29. | Ardila CM, González-Arroyave D. Precision at scale: Machine learning revolutionizing laparoscopic surgery. World J Clin Oncol. 2024;15:1256-1263. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Kuemmerli C, Toti JMA, Haak F, Billeter AT, Nickel F, Guidetti C, Santibanes M, Vigano L, Lavanchy JL, Kollmar O, Seehofer D, Abu Hilal M, Di Benedetto F, Clavien PA, Dutkowski P, Müller BP, Müller PC. Towards a Standardization of Learning Curve Assessment in Minimally Invasive Liver Surgery. Ann Surg. 2024;281:252-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/