Published online Mar 18, 2026. doi: 10.5500/wjt.v16.i1.112811

Revised: August 20, 2025

Accepted: December 2, 2025

Published online: March 18, 2026

Processing time: 161 Days and 4.3 Hours

Organ transplantation has emerged as a globally prevalent therapeutic modality for end-stage organ failure, yet the post-transplantation trajectory is increasingly complicated by a spectrum of metabolic sequelae, with obesity emerging as a cri

To systematically review the multifactorial mechanisms underlying obesity following organ transplantation and to integrate evidence from pharmacological, behavioral, and molecular perspectives, thereby providing a foundation for tar

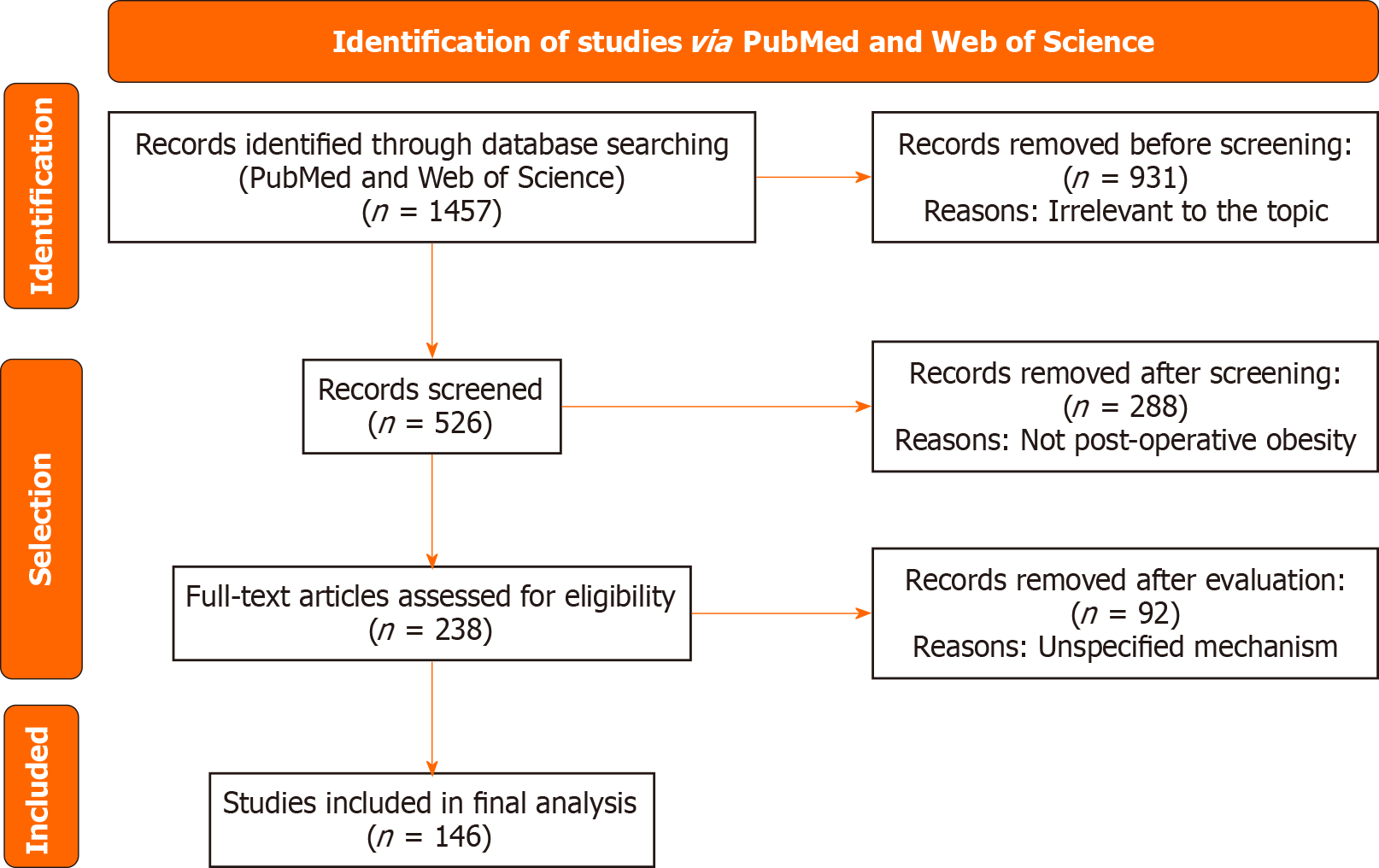

We conducted a systematic search in PubMed and Web of Science for literature published from 2020 to 15 July 2025. The search strategy incorporated terms including “obesity”, “overweight” and “post organ transplantation”. Only ran

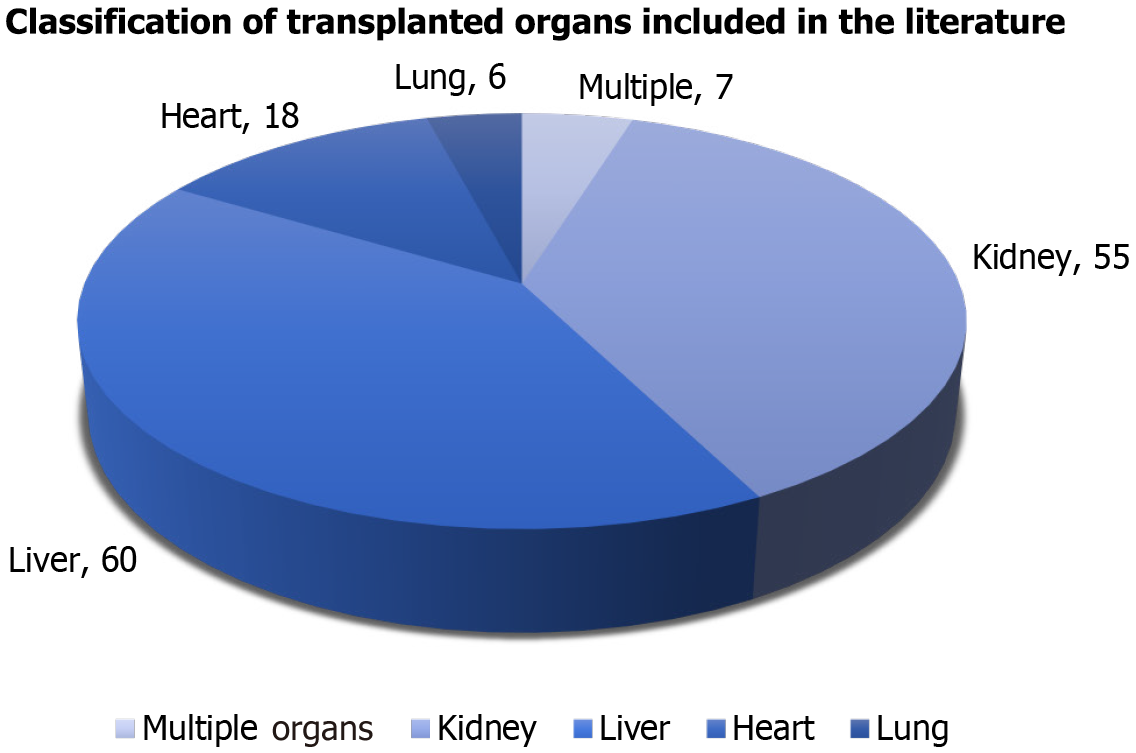

A total of 1457 articles were initially identified, of which 146 met the inclusion criteria. These studies encompassed liver, kidney, heart, and lung transplant recipients. Key findings indicate that immunosuppressive drugs-especially corti

Post-transplant obesity arises from a complex interplay of pharmacological, behavioral, and molecular factors. A multidisciplinary approach-incorporating pharmacological modification, nutritional management, physical activity, and molecular-targeted therapies-is essential to mitigate obesity and improve transplant outcomes. Further large-scale and mechanistic studies are warranted to establish evidence-based preventive and treatment strategies.

Core Tip: Organ transplantation for end-stage failure faces post-transplant obesity, a key challenge. This review analyzes its multifactorial causes: Immunosuppressants (corticosteroids, calcineurin inhibitors) disrupt metabolism, hypoactivity worsens energy imbalance, poor diet promotes weight gain, and molecularly, immunosuppressants affect adipokines and insulin, with inflammation driving lipid accumulation. It offers a framework for mitigation strategies.

- Citation: Chen KR, Wu LZ, Huang YN, Zhuang SY, Chen ZY, Xu B, Xu TC. Pathogenic analysis of post-transplantation obesity: A comprehensive systematic review. World J Transplant 2026; 16(1): 112811

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3230/full/v16/i1/112811.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5500/wjt.v16.i1.112811

Organ transplantation has become a pivotal therapeutic approach for end-stage organ failure. With advancements in surgical techniques, immunosuppressive regimens, and organ allocation systems, the global volume of transplants continues to rise[1]. Transplantation significantly improves prognosis in patients with end-stage cardiac, hepatic, and renal diseases[2,3]. However, post-transplant metabolic complications-including hypertension, diabetes, and obesity-adversely affect long-term patient health and graft survival[4,5]. These interrelated metabolic disturbances elevate cardiovascular risks and compromise therapeutic outcomes and quality of life[6,7].

Post-transplant obesity represents a prominent metabolic concern, exhibiting high prevalence across various transplant types. For instance, obesity occurs in 14% of lung transplant recipients, with overweight individuals and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients at particularly elevated risk[8]. Obesity not only promotes pathological fat accumulation but also triggers inflammatory responses, insulin resistance (IR), and other metabolic dysregulations, potentially influencing graft rejection and long-term survival[9,10].

Given the prevalence and clinical significance of post-transplant obesity, this article aims to provide a systematic introductory review for novice clinicians and basic medical researchers in the field of organ transplantation. By synthesizing multidisciplinary foundational evidence, it seeks to help readers establish a comprehensive conceptual framework for understanding the mechanisms and management strategies of post-transplant obesity (Figure 1, Supplementary Figure 1).

A systematic search was conducted in PubMed and Web of Science for studies published up from 2020 to 15 July 2025, using the items and free words: ((overweight) OR (obesity)) AND ((post transplantation) OR (post organ trans

| Total | Theme-independent | Non-postoperative obesity | Mechanism-free |

| 298 | 283 | 6 | 2 |

| 290 | 109 | 90 | 61 |

| 290 | 270 | 9 | 11 |

| 290 | 22 | 176 | 12 |

| 289 | 247 | 7 | 6 |

| 1457 | 931 | 288 | 92 |

| Total | Liver | Kidney | Heart | Lung |

| 7 | / | 3 | 4 | / |

| 30 | 1 | 7 | 19 | 3 |

| 0 | / | / | / | / |

| 80 | 6 | 32 | 24 | 13 |

| 29 | / | 13 | 13 | 2 |

| 146 | 7 | 55 | 60 | 18 |

Immunosuppressive therapy is indispensable for maintaining allograft survival after solid organ transplantation; however, it also constitutes a primary pathogenic driver of post-transplantation obesity. Among the immunopharmacological agents commonly employed, corticosteroids and calcineurin inhibitors (CNIs)-particularly cyclosporine and tacrolimus-are most frequently implicated in metabolic complications, including excessive weight gain, IR, and dyslipidemia (Table 3)[11-18].

| Immunosuppressant | Major metabolic effects | Proposed mechanisms | Ref. |

| Glucocorticoids | Hyperphagia, central adiposity, insulin resistance | ↑ Appetite via central regulation; ↓ adiponectin, ↑ leptin resistance | [11] |

| Tacrolimus (CNI) | Impaired glucose tolerance, β-cell apoptosis | Inhibition of PI3K/Akt/mTOR; microbiome alterations | [15] |

| Cyclosporine (CNI) | Dyslipidemia, insulin resistance | Mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress | [18] |

| Mycophenolate Mofetil | Dyslipidemia | Synergistic effects when combined with steroids/CNIs | [18] |

| Azathioprine | Less studied; associated with lipid alterations | Likely indirect or combined effects | [18] |

Glucocorticoids: Essential immunosuppressants with a heavy metabolic cost. Glucocorticoids remain a cornerstone of induction and maintenance immunosuppression but are well known for their profound metabolic side effects. These agents stimulate hyperphagia by increasing fasting hunger and altering central regulation of appetite. Functional neuroimaging studies reveal that stress-level glucocorticoids reduce cerebral blood flow in regions responsible for appetite control, thereby promoting increased energy intake[11]. Simultaneously, they upregulate lipogenesis, redis

CNIs: Potent immunosuppressants with diabetogenic consequences. CNIs, particularly tacrolimus, are central to post-transplant immunosuppression but are increasingly recognized for their diabetogenic effects. Tacrolimus impairs pancreatic β-cell function through inhibition of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway, leading to decreased insulin secretion and increased β-cell apoptosis[15]. Beyond its direct pancreatic toxicity, tacrolimus may also induce nephrotoxicity and pancreatic injury, both of which exacerbate glucose dysregulation[16]. Recent research further implicates the gut microbiome as a mediator of CNI-induced metabolic disturbances; alterations in microbial composition and metabolite production have been shown to contribute to impaired glucose tolerance in preclinical models[17]. Colle

Other immunosuppressants and combined effects: Other immunosuppressive agents, such as azathioprine and mycop

In aggregate, immunosuppressive drugs exert multifaceted metabolic effects through endocrine, neural, and microbiota-mediated pathways. They disrupt glucose-insulin regulation, stimulate lipid accumulation, and impair energy balance, while also interfering with satiety signaling and adipokine function[19-24]. These mechanisms converge to create a metabolic environment conducive to obesity development, making immunopharmacological modulation both a chal

| Index | Adult | Child | Activity | Diet | Ref. |

| Heart transplant | 25-40 per cent of patients’ obesity post-transplantation | The lowest incidence of obesity post-transplantation, the lowest risk of obesity relative to other organ groups | Limited heart function and restricted exercise tolerance | The aggressive use of supplemental nutrition via feeding tubes | [23,24] |

| Kidney transplantation | 21% of patients with CKD have obesity, and CKD patients are the main population for kidney transplantation | The highest incidence of obesity, a cumulative incidence 5-year post-transplantation of 27% | Reduced activity due to dialysis | Supplementary caloric intake via peritoneal dialysis | [22,23] |

| Liver transplantation | 23% of liver transplant candidates have class I obesity, 10% have class II, and 4% have class III | The probability of obesity is lower than that of kidney transplantation and higher than that of heart transplantation | have a critical clinical status at time of transplantation in order to reduce activites | have a critical clinical status at time of transplantation in order to reduce food intake | [23,24] |

Transplant surgery is highly invasive, causing significant physiological impact. Traditionally, patients often remain sedentary post-operation, with many facing reduced mobility due to physical or psychological barriers. Concurrently, increased food intake is common for recovery. Studies show higher physical activity reduces daily energy intake and elevates basal metabolic expenditure[19]. Body weight gain is determined by the balance between energy intake and total energy expenditure, which comprises basal metabolic rate (BMR) and activity-induced energy expenditure[20]. Reduced postoperative activity following transplantation lowers energy expenditure, exacerbating positive energy balance and contributing to post-transplant obesity.

Organ transplantation benefits patients, yet post-transplant weight gain significantly threatens recovery and long-term health. Studies indicate recipients consistently shift towards dietary patterns high in calorie-dense, fatty, and sugary foods.

Core immunosuppressants-glucocorticoids and CNIs-exhibit adipogenic effects. Glucocorticoids stimulate hypo

Influences on adipokine signaling pathways: Immunosuppressants, particularly CNIs like tacrolimus, disrupt adi

Tacrolimus upregulates leptin expression but induces leptin resistance by impairing JAK2/STAT3 signaling in hypothalamic neurons, which normally suppresses appetite and hepatic gluconeogenesis[25,26]. Leptin resistance exacerbates hyperphagia and promotes ectopic lipid deposition in the liver and muscle, further aggravating IR[26].

Tacrolimus reduces adiponectin secretion by 30%–50% in adipose tissue, mediated through inhibition of PPARγ transcriptional activity[25,27]. Low adiponectin diminishes AMPK activation in skeletal muscle and liver, leading to reduced phosphorylation of acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) and impairing fatty acid oxidation. Enhanced hepatic gluconeogenesis via unopposed mTOR/S6K1 signaling[26,27]. Adiponectin's tumor-suppressive and metabolic regulatory roles in glioma cells via AMPK activation further underscore its systemic importance[27].

Immunosuppressants synergize with transplantation-induced inflammation to skew adipokine profiles. Pro-inflammatory cytokines [e.g., tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α), interleukin (IL)-6] from adipose tissue macrophages suppress adiponectin transcription and amplify leptin resistance[26,28]. Oxidative stress triggered by tacrolimus activates NF-κB in adipocytes, increasing resistin and visfatin secretion. These adipokines directly inhibit insulin receptor substrate 1 (IRS1) tyrosine phosphorylation in skeletal muscle, blunting GLUT4 translocation[25,29] (Table 5).

| Adipokine | Change | Mechanism | Metabolic Consequence | Ref. |

| Leptin | ↑ Secretion | PPARγ inhibition→Leptin resistance | ↑Appetite,↑ hepatic glucose output | [25,26] |

| Adiponectin | ↓Secretion (30%–50%) | Impaired PPARγ/AMPK axis | ↓Fatty acid oxidation→lipid accumulation | [25,27] |

| Resistin | ↑ Secretion | NF-κB activation by oxidative stress | IRS1 inhibition →↓glucose uptake | [25,29] |

The combined adipokine dysregulation converges on insulin signaling defects. AMPK suppression (from low adiponectin) and mTOR overactivation (from high leptin/resistin) inhibit IRS1/PI3K/Akt signaling, reducing glucose uptake in muscle and adipose tissue[26,27]. Mitochondrial dysfunction in β-cells, driven by tacrolimus-induced oxidative stress, further compromises insulin secretion, creating a vicious cycle of hyperglycemia[25].

Recent studies highlight that gut microbiota alterations under immunosuppressants exacerbate adipokine dysfunction via bile acid signaling, which represses adipose FXR and amplifies inflammation. Targeting adipokine signaling (e.g., with AMPK activators like metformin or adiponectin mimetics) represents a promising strategy to mitigate PTDM[26,27].

Effects on the adipogenesis pathway: After organ transplantation, the incidence of obesity is significantly increased in patients, a phenomenon that is deeply influenced at the molecular level by the transplant-induced inflammatory cascade and oxidative stress, both of which activate the adipogenic pathway through a complex mechanism that promotes an abnormal accumulation of lipids in adipose tissue[30-39]. After transplantation, the activation of the immune system and the allogeneic reaction of the transplanted organ often triggers systemic inflammation, and the inflammatory cascade network characterized by the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (e.g., TNF-α, IL-6, and IL-1β) is formed, which can directly or indirectly activate adipogenic pathways through multiple pathways. On the one hand, inflammatory signals can activate signaling pathways such as NF-κB and JAK/STAT, and upregulate the expression of key adipogenic transcription factors (e.g., PPARγ and C/EBPα). For example, TNF-α can inhibit the negative regulator of PPARγ, SIRT1, or directly promote its phosphorylation, which enhances the transcriptional activity of PPARγ, and drives the differentiation of preadipocytes to mature adipocytes[40,41]. Meanwhile, the inflammatory environment can also alter the expression of adipogenesis-related genes with the help of epigenetic mechanisms (e.g., DNA methylation, histone acetylation), such as IL-6 activating the DNA methyltransferase DNMT, inhibiting the expression of the adipocyte differentiation suppressor Pref-1, and deregulating the inhibition of adipogenesis[36,42]. In addition, extracellular matrix sclerosis caused by inflammatory response can activate mechanotransduction through integrin signaling pathway to promote the proliferation and differentiation of adipocyte precursors, and the abnormal deposition of ECM components can also regulate adipocyte-matrix interactions and affect the efficiency of adipogenesis[34,35]. On the other hand, oxidative stress induced by post-transplantation ischemia-reperfusion injury, immunosuppressant use and other factors, characterized by overproduction of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and reactive nitrogen species, can also activate the adipogenic pathway, and ROS can activate redox-sensitive transcription factors, such as Nrf2, to up-regulate adipo

| Mechanism type | Specific ways | Key molecules/factors | Effect |

| Inflammatory cascade activates adipogenic pathways | Activation of signaling pathways[40,41] | NF-Kb, JAK/STAT, TNF-α, SIRT1, PPARy, C/EBPα | Inflammatory signaling activates NF-κB, JAK/STAT pathways, TNF-α enhances PPARV activity by inhibiting SIRT1 or promoting its phosphorylation and up-regulation of key adipogenic transcription factors drives preadipocyte differentiation |

| Epigenetic regulation[36,42] | IL-6, DNMT, Pref-1 | Activation of DNMT by IL-6 and inhibition of Pref-1 release the suppression of adipogenesis and alteration of adipogenesis-related gene expression by epigenetic mechanisms | |

| Extracellular matrix effects[34,35] | Integrin signaling pathway ECM components | Inflammation leads to extracellular matrix sclerosis, which promotes proliferation and differentiation of adipocyte precursors through activation of mechanotransduction by the integrin signaling pathway; aberrant deposition of ECM components regulates adipocyte-matrix interactions and affects adipogenic efficiency | |

| Oxidative stress activates adipogenic pathways | Transcription factor activation[33,38] | ROS, Nrf2, SREBP-1c | ROS activate redox-sensitive transcription factors such as Nrf2, which binds to the SREBP.1c promoter under chronic oxidative stress to directly promote adipogenic gene transcription |

| lipid peroxidation[33,38] | 4-Hydroxynonenal, ACC, FAS | Oxidative stress leads to lipid peroxidation to generate aldehyde products, and modification of sulfhydryl groups of key adipogenic proteins, such as ACC. FAS, alters their enzymatic activity or stability and promotes lipid synthesis | |

| Metabolic reprogramming[32,37] | mitochondrial membrane potential, ATP, Acetyl Coenzyme A, AMPK/mTOR pathway | Oxidative stress induces the loss of mitochondrial membrane potential, ATP synthesis decreases cellular energy metabolism from oxidative phosphorylation to glycolysis, increases the generation of acetyl-coenzyme A, which provides substrates for fat synthesis, and at the same time activates the AMPK/mTOR pathway to promote the proliferation and differentiation of adipocyte precursors | |

| Inflammation and oxidative stress synergize | Signal network synergy[33,39] | ROS, IKK complex, NF-κB, TNF-α, NLRP3inflammatory, vesicle | ROS activate IKK complex, promote NFKB nuclear translocation, and up-regulate inflammatory cytokines and adipogenic gene expression: TNF-α induces mitochondrial ROS production, and ROS activate NLRP3 inflammatory vesicles, forming a positive feedback loop and continuously activating the adipogenic pathway |

One critical avenue for intervention lies in the refinement of immunosuppressive protocols. Reducing the cumulative exposure to metabolically toxic agents, particularly glucocorticoids and tacrolimus, may mitigate their obesogenic effects. Strategies under investigation include dose minimization, steroid-sparing regimens[7], and substitution with metabolically neutral or protective agents. For instance, rapamycin has demonstrated potential protective effects against tacro

Microbiota-targeted strategies also represent a promising adjunct. Vancomycin has been shown to alleviate tacrolimus-induced hyperglycemia by eliminating bacterial β-glucuronidase activity, highlighting the potential for microbiome modulation as a therapeutic strategy[43]. Similarly, agents such as Reg3 g, a regenerating islet-derived protein, have shown efficacy in restoring mitochondrial function and improving pancreatic β-cell performance under tacrolimus exposure[44,45].

Integrated lifestyle interventions combining structured exercise and personalized nutrition are pivotal for mitigating post-transplantation obesity. Tailored aerobic/resistance training (e.g., 30-45 minutes/day, 5 days/week) counters sedentariness and immunosuppressant-induced metabolic suppression. In pediatric renal recipients, such regimens improve insulin sensitivity and reduce adiposity[45], while supervised programs in lung transplant patients significantly lower BMI trajectories[46].

Dietary management must address hyperphagia and cultural barriers. Mediterranean-style diets (high in monounsaturated fats/fiber) reduce LDL cholesterol and weight regain in liver recipients[47]; Family-centered education and meal-timing strategies (e.g., daytime high-protein meals) curb nocturnal overeating and improve adherence[45,46].

Pharmacological interventions targeting immunosuppressant-disrupted molecular pathways-particularly adipokine signaling and adipogenic cascades-hold transformative potential for mitigating post-transplantation obesity. Key strategies focus on AMPK activation, a central regulator countering lipid accumulation and IR: Natural compounds like Saikosaponin A/D inhibit adipogenesis in 3T3-L1 adipocytes by phosphorylating AMPK and MAPK, thereby sup

Based on the screened literature data, studies on liver and lung transplantation remain relatively scarce. Future research should prioritize investigating the mechanisms underlying post-transplant obesity in these specific organ co

Current evidence demonstrates the complexity of etiological mechanisms and therapeutic strategies for post-transplantation obesity. Research indicates that the administration of immunosuppressive agents, postoperative lifestyle modifications, and dysregulation of molecular pathways collectively contribute to obesity development. While optimi

The authors would like to express their profound gratitude to all contributors included in the RCTs for their efforts in identifying and supplying pertinent data related to their respective studies.

| 1. | Silva JT, Fernández-Ruiz M, Aguado JM. Prevention and therapy of viral infections in patients with solid organ transplantation. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin (Engl Ed). 2021;39:87-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 2. | Agostini C, Buccianti S, Risaliti M, Fortuna L, Tirloni L, Tucci R, Bartolini I, Grazi GL. Complications in Post-Liver Transplant Patients. J Clin Med. 2023;12:6173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 3. | Gheorghe G, Diaconu CC, Bungau S, Bacalbasa N, Motas N, Ionescu VA. Biliary and Vascular Complications after Liver Transplantation-From Diagnosis to Treatment. Medicina (Kaunas). 2023;59:850. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Sharif A, Chakkera H, de Vries APJ, Eller K, Guthoff M, Haller MC, Hornum M, Nordheim E, Kautzky-Willer A, Krebs M, Kukla A, Kurnikowski A, Schwaiger E, Montero N, Pascual J, Jenssen TG, Porrini E, Hecking M. International consensus on post-transplantation diabetes mellitus. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2024;39:531-549. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 25.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Braekman E, De Bruyne R, Vandekerckhove K, Prytula A. Etiology, risk factors and management of hypertension post liver transplantation. Pediatr Transplant. 2024;28:e14630. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Iacob S, Gheorghe L. Long Term Follow-up of Liver Transplant Recipients: Considerations for Non-transplant Specialists. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2021;30:283-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Popović L, Bulum T. New Onset Diabetes After Organ Transplantation: Risk Factors, Treatment, and Consequences. Diagnostics. 2025;15:284. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Jomphe V, Bélanger N, Beauchamp-Parent C, Poirier C, Nasir BS, Ferraro P, Lands LC, Mailhot G. New-onset Obesity After Lung Transplantation: Incidence, Risk Factors, and Clinical Outcomes. Transplantation. 2022;106:2247-2255. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kawai T, Autieri MV, Scalia R. Adipose tissue inflammation and metabolic dysfunction in obesity. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2021;320:C375-C391. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 101] [Cited by in RCA: 1258] [Article Influence: 209.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kanbay M, Copur S, Ucku D, Zoccali C. Donor obesity and weight gain after transplantation: two still overlooked threats to long-term graft survival. Clin Kidney J. 2023;16:254-261. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Bini J, Parikh L, Lacadie C, Hwang JJ, Shah S, Rosenberg SB, Seo D, Lam K, Hamza M, De Aguiar RB, Constable T, Sherwin RS, Sinha R, Jastreboff AM. Stress-level glucocorticoids increase fasting hunger and decrease cerebral blood flow in regions regulating eating. Neuroimage Clin. 2022;36:103202. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Akalestou E, Genser L, Rutter GA. Glucocorticoid Metabolism in Obesity and Following Weight Loss. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2020;11:59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 78] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Lengton R, Iyer AM, van der Valk ES, Hoogeveen EK, Meijer OC, van der Voorn B, van Rossum EFC. Variation in glucocorticoid sensitivity and the relation with obesity. Obes Rev. 2022;23:e13401. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Perez-Leighton C, Kerr B, Scherer PE, Baudrand R, Cortés V. The interplay between leptin, glucocorticoids, and GLP1 regulates food intake and feeding behaviour. Biol Rev Camb Philos Soc. 2024;99:653-674. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Tong L, Li W, Zhang Y, Zhou F, Zhao Y, Zhao L, Liu J, Song Z, Yu M, Zhou C, Yu A. Tacrolimus inhibits insulin release and promotes apoptosis of Min6 cells through the inhibition of the PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway. Mol Med Rep. 2021;24:658. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 4.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Chen X, Hu K, Shi HZ, Zhang YJ, Chen L, He SM, Wang DD. Syk/BLNK/NF-κB signaling promotes pancreatic injury induced by tacrolimus and potential protective effect from rapamycin. Biomed Pharmacother. 2024;171:116125. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Jiang Z, Qian M, Zhen Z, Yang X, Xu C, Zuo L, Jiang J, Zhang W, Hu N. Gut microbiota and metabolomic profile changes play critical roles in tacrolimus-induced diabetes in rats. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2024;14:1436477. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Akman B, Uyar M, Afsar B, Sezer S, Ozdemir FN, Haberal M. Lipid profile during azathioprine or mycophenolate mofetil combinations with cyclosporine and steroids. Transplant Proc. 2007;39:135-137. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Berge J, Hjelmesaeth J, Hertel JK, Gjevestad E, Småstuen MC, Johnson LK, Martins C, Andersen E, Helgerud J, Støren Ø. Effect of Aerobic Exercise Intensity on Energy Expenditure and Weight Loss in Severe Obesity-A Randomized Controlled Trial. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2021;29:359-369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Bellicha A, van Baak MA, Battista F, Beaulieu K, Blundell JE, Busetto L, Carraça EV, Dicker D, Encantado J, Ermolao A, Farpour-Lambert N, Pramono A, Woodward E, Oppert JM. Effect of exercise training on weight loss, body composition changes, and weight maintenance in adults with overweight or obesity: An overview of 12 systematic reviews and 149 studies. Obes Rev. 2021;22 Suppl 4:e13256. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 178] [Article Influence: 35.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Cho JH, Suh S. Glucocorticoid-Induced Hyperglycemia: A Neglected Problem. Endocrinol Metab (Seoul). 2024;39:222-238. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Karolin A, Genitsch V, Sidler D. Calcineurin Inhibitor Toxicity in Solid Organ Transplantation. Pharmacology. 2021;106:347-355. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Ghanem OM, Pita A, Nazzal M, Johnson S, Diwan T, Obeid NR, Croome KP, Lim R, Quintini C, Whitson BA, Burt HA, Miller C, Kroh M; SAGES & ASTS. Obesity, organ failure, and transplantation: a review of the role of metabolic and bariatric surgery in transplant candidates and recipients. Surg Endosc. 2024;38:4138-4151. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Bondi BC, Banh TM, Vasilevska-Ristovska J, Szpindel A, Chanchlani R, Hebert D, Solomon M, Dipchand AI, Kim SJ, Ng VL, Parekh RS. Incidence and Risk Factors of Obesity in Childhood Solid-Organ Transplant Recipients. Transplantation. 2020;104:1644-1653. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Shi HR, Li SD, Wang K, Chen YX, Li ZC, Zhang Y, Zhu XY, Gao L, Jiang HT. [Research advances in the impact of tacrolimus on glucose metabolism after kidney transplantation]. Qiguan Yizhi. 2025;16:778-784. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 26. | Rai PS, Bhandary YP, Shivarajashankara YM, Akarsha B, Bhandary R, Prajna RH, Namrata KG, Savin CG, Alva P, Katyayani P, Shetty S, Sudhakar TJ. Interlinking the Cross Talk on Branched Chain Amino Acids, Water Soluble Vitamins and Adipokines in the Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Etiology. Endocr Metab Immune Disord Drug Targets. 2025;25:757-766. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Sun P, Huo K, Liu F, Cheng Y, Chen C, Han J, Yu J. Regulation and molecular mechanism of adiponectin on the proliferation, apoptosis, autophagy, and chemosensitivity of LN18 Glioma cell line. Cell Mol Biol (Noisy-le-grand). 2024;70:178-186. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Lai HC, Chen PH, Tang CH, Chen LW. IL-10 Enhances the Inhibitory Effect of Adipose-Derived Stromal Cells on Insulin Resistance/Liver Gluconeogenesis by Treg Cell Induction. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25:8088. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | McDonnell JM, Darwish S, Butler JS, Buckley CT. The Role of Adipokines in Spinal Disease: A Narrative Review. JOR Spine. 2025;8:e70083. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Gao W, Du L, Li N, Li Y, Wu J, Zhang Z, Chen H. Dexmedetomidine attenuates myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury in hyperlipidemic rats by inhibiting inflammation, oxidative stress and NF-κB. Chem Biol Drug Des. 2023;102:1176-1185. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Li X, Cheng Y, Li J, Liu C, Qian H, Zhang G. Torularhodin Alleviates Hepatic Dyslipidemia and Inflammations in High-Fat Diet-Induced Obese Mice via PPARα Signaling Pathway. Molecules. 2022;27:6398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Steinberg GR, Hardie DG. New insights into activation and function of the AMPK. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2023;24:255-272. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 612] [Article Influence: 204.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Bellezza I, Giambanco I, Minelli A, Donato R. Nrf2-Keap1 signaling in oxidative and reductive stress. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Res. 2018;1865:721-733. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 565] [Cited by in RCA: 1405] [Article Influence: 175.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 34. | Li J, Xu R. Obesity-Associated ECM Remodeling in Cancer Progression. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14:5684. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Rahimi A, Rasouli M, Heidari Keshel S, Ebrahimi M, Pakdel F. Is obesity-induced ECM remodeling a prelude to the development of various diseases? Obes Res Clin Pract. 2023;17:95-101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Hamjane N, Benyahya F, Nourouti NG, Mechita MB, Barakat A. Cardiovascular diseases and metabolic abnormalities associated with obesity: What is the role of inflammatory responses? A systematic review. Microvasc Res. 2020;131:104023. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 8.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Wang X, Li G, Liu J, Gong W, Li R, Liu J. GSK621 ameliorates lipid accumulation via AMPK pathways and reduces oxidative stress in hepatocytes in vitro and in obese mice in vivo. Life Sci. 2025;374:123687. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Ahmed B, Sultana R, Greene MW. Adipose tissue and insulin resistance in obese. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021;137:111315. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 610] [Article Influence: 122.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Moghbeli M, Khedmatgozar H, Yadegari M, Avan A, Ferns GA, Ghayour Mobarhan M. Cytokines and the immune response in obesity-related disorders. Adv Clin Chem. 2021;101:135-168. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Kandhaya-Pillai R, Yang X, Tchkonia T, Martin GM, Kirkland JL, Oshima J. TNF-α/IFN-γ synergy amplifies senescence-associated inflammation and SARS-CoV-2 receptor expression via hyper-activated JAK/STAT1. Aging Cell. 2022;21:e13646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 81] [Article Influence: 20.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Lee S, Lee M. MEK6 Overexpression Exacerbates Fat Accumulation and Inflammatory Cytokines in High-Fat Diet-Induced Obesity. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:13559. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Kim AY, Park YJ, Pan X, Shin KC, Kwak SH, Bassas AF, Sallam RM, Park KS, Alfadda AA, Xu A, Kim JB. Obesity-induced DNA hypermethylation of the adiponectin gene mediates insulin resistance. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7585. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 121] [Cited by in RCA: 177] [Article Influence: 16.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Li P, Zhang R, Zhou J, Guo P, Liu Y, Shi S. Vancomycin relieves tacrolimus-induced hyperglycemia by eliminating gut bacterial beta-glucuronidase enzyme activity. Gut Microbes. 2024;16:2310277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Li S, Zhou H, Xie M, Zhang Z, Gou J, Yang J, Tian C, Ma K, Wang CY, Lu Y, Li Q, Peng W, Xiang M. Regenerating islet-derived protein 3 gamma (Reg3g) ameliorates tacrolimus-induced pancreatic β-cell dysfunction in mice by restoring mitochondrial function. Br J Pharmacol. 2022;179:3078-3095. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Stabouli S, Polderman N, Nelms CL, Paglialonga F, Oosterveld MJS, Greenbaum LA, Warady BA, Anderson C, Haffner D, Desloovere A, Qizalbash L, Renken-Terhaerdt J, Tuokkola J, Walle JV, Shaw V, Mitsnefes M, Shroff R. Assessment and management of obesity and metabolic syndrome in children with CKD stages 2-5 on dialysis and after kidney transplantation-clinical practice recommendations from the Pediatric Renal Nutrition Taskforce. Pediatr Nephrol. 2022;37:1-20. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Emsley C, Snell G, Paul E, Fuller L, Paraskeva M, Nyulasi I, King S. Can we HALT obesity following lung transplant? A Dietitian- and Physiotherapy-directed pilot intervention. Clin Transplant. 2022;36:e14763. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Spillman LN, Stowe E, Madden AM, Rennie KL, Oude Griep LM, Allison M, Kenney L, O'Connor C, Griffin SJ. Diet and physical activity interventions to improve cardiovascular disease risk factors in liver transplant recipients: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Transplant Rev (Orlando). 2024;38:100852. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Lim SH, Lee HS, Han HK, Choi CI. Saikosaponin A and D Inhibit Adipogenesis via the AMPK and MAPK Signaling Pathways in 3T3-L1 Adipocytes. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:11409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Liang C, Li Y, Bai M, Huang Y, Yang H, Liu L, Wang S, Yu C, Song Z, Bao Y, Yi J, Sun L, Li Y. Hypericin attenuates nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and abnormal lipid metabolism via the PKA-mediated AMPK signaling pathway in vitro and in vivo. Pharmacol Res. 2020;153:104657. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 46] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/