Published online Mar 18, 2026. doi: 10.5500/wjt.v16.i1.113075

Revised: September 12, 2025

Accepted: November 26, 2025

Published online: March 18, 2026

Processing time: 153 Days and 11.2 Hours

Living donor kidney transplantation is the optimal method of long-term renal replacement therapy. Minimally invasive donor nephrectomy techniques, such as robot-assisted (RALDN) and hand-assisted (HALDN) laparoscopic procedures, are well-established in high-income countries and are being increasingly adopted worldwide. Nevertheless, no studies have reported surgical outcomes of RALDN donor nephrectomy from a United Kingdom center to date.

To compare surgical outcomes between RALDN and HALDN laparoscopic donor nephrectomy in a United Kingdom high-volume living kidney donor transplant program.

A case-control matching analysis was performed based on the following para

In this cohort of 140 living donors (70 RALDN vs 70 HALDN), donor and recipient outcomes were equivalent across key metrics: Pain scores, overall complication rates, readmissions, reoperations, and creatinine levels at 30 days and 1 year. Recipient long-term renal function did not differ between groups. Operative time for RALDN decreased significantly over the study period, indicating progressive improvement along the learning curve. Although RALDN was associated with a modestly longer mean warm ischaemia time (3.53 minutes vs 2.76 minutes, P < 0.001) and extended hospital stay (4.21 days vs 3.17 days, P < 0.001), these did not translate into any disadvantage in clinical outcomes.

In this first United Kingdom comparative cohort, RALDN demonstrated excellent safety and efficacy, even in the early phase of our programme, matching the outcomes of the well-established, gold-standard HALDN approach. Moreover, the pronounced learning-curve trajectory suggests considerable potential for further improvements in robotic surgical outcomes as the programme matures.

Core Tip: This is the first United Kingdom study to compare robot-assisted (RALDN) and hand-assisted laparoscopic donor nephrectomy outcomes. In a matched cohort of 140 donors, both techniques achieved equivalent safety and efficacy, with no differences in donor or recipient renal function at one year. Although RALDN had longer warm ischaemia and hospital stay, outcomes improved as the surgical team advanced along the learning curve. This work demonstrates the feasibility of establishing RALDN in a high-volume United Kingdom center without prior robotic experience, providing a foundation for further integration of robotic platforms in kidney transplantation.

- Citation: Christou CD, Antoniadis S, Majumder A, Zakri R, Olsburgh J, Callaghan C, Papadakis G, Sran K, Drage M, Decaestecker K, Challacombe B, Kessaris N, Loukopoulos I. Robot-assisted vs hand-assisted laparoscopic donor nephrectomy in the United Kingdom: Equivalent outcomes in the first national series. World J Transplant 2026; 16(1): 113075

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3230/full/v16/i1/113075.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5500/wjt.v16.i1.113075

Living donor kidney transplantation is the gold standard for treating end-stage kidney disease[1]. According to the Global Observatory on Donation and Transplantation, 39% of all kidney transplants worldwide are enabled by living donors[2]. The prevalence of chronic kidney disease has been increasing exponentially, now affecting more than 1 in every ten individuals worldwide, with chronic kidney disease projected to become the 5th most common cause of death by 2040[3]. As a result, there is a clear mandate to expand both the deceased and living kidney donor pools. Current stra

When it comes to living kidney donors, the priority is to ensure maximum safety with minimal disruption to their everyday lives. Open donor nephrectomy is associated with considerable postoperative pain, higher analgesic require

Robotic surgery offers potential advantages over conventional laparoscopy, including enhanced instrument manoeuvrability, fine motor control, reduced hand tremor, a stable camera view, improved surgeon ergonomics with reduced physical strain, precise energy delivery, smaller incisions, controlled movements, and improved reach[7-9]. Whether these advantages translate into significantly improved surgical outcomes that justify the higher costs remains a subject of debate[8].

In living donor nephrectomies, while several studies have evaluated the safety, pain outcomes, and recovery times between the two approaches, the existing literature offers conflicting evidence[10-13]. Meta-analyses have suggested that robot-assisted (RALDN) nephrectomy may offer superior outcomes in terms of reduced pain and faster recovery, but it also comes with drawbacks such as longer operative and primary warm ischaemia times[14]. Furthermore, many existing studies lack consistency in their assessment of long-term recipient outcomes, particularly regarding kidney function post-transplant, with some reporting no significant differences between the two techniques, while others highlight advantages specific to robotic procedures. Importantly, none of the current studies is based on data from United Kingdom settings, leaving a gap in understanding the nuances of these procedures in different healthcare environments.

The aim of our study was to compare surgical outcomes between RALDN and hand-assisted (HALDN) laparoscopic donor nephrectomy in a United Kingdom high-volume living kidney donor transplant program. To achieve that, we conducted an observational retrospective case-control matching study. To our knowledge, this is the first comparative study investigating the surgical outcomes of RALDN in the United Kingdom.

The RALDN program was launched following the approval of local committees for new surgical procedures. A new procedure request was completed and shared with the head of patient safety, the chief of surgery, the Governance Committee of the Transplant Research and Urology Directorate, the Cancer and Surgery Governance Committee, and the Robotic Governance Committee. The above approved a pilot phase of 15 RALDN with the following inclusion criteria: Left side nephrectomy, single renal artery and vein, body mass index (BMI) < 30 kg/m2, no previous abdominal surgeries, and patient preference. The primary surgeon of the RALDN program operated under a mentor for the first case. The mentor provided remote support and oversight for the rest of the pilot phase. Following the completion of the 15-patient pilot phase, the RALDN acquired sign-off from the committees to expand to all potential kidney donors. The only para

This study constitutes an observational, retrospective, cohort study conducted from January 2019 to January 2024. STROBE guidelines for observational studies were applied[15]. All 493 donors who underwent living donor nephrectomy at Guy’s Hospital during that time were eligible for inclusion. The initial population consisted of 236 male donors (48%). The average age at donation was 44 ± 11.7 years old. Of these, 435 (88.2%) were left nephrectomies, and in 419 (85%) cases, there was a single artery. The average BMI at donation was 26.1 ± 3.5 kg/m2 and 94 (19.1%) of the donors had previous abdominal surgery. For the pilot phase, donor-related clinical criteria were considered to assign cases to either the RALDN or HALDN group. Thus, a selection bias is introduced between the two groups. We resolved that by con

RALDN laparoscopic donor nephrectomy: One surgeon performed all RALDN procedures using the Da Vinci X or Xi system (Intuitive Surgical, Sunnyvale, CA, United States). The donor is positioned laterally, similar to the HALDN technique. The need to break the operating table depends on the donor’s body habitus. A 6 cm, low abdomen, transverse incision is made at the side of the kidney to be removed, centered above the lateral margin of the rectus muscle. A GelPort® system (Applied Medical, Rancho Santa Margarita, CA, United States) is inserted. An 8 mm robotic port and a 12 mm assistant port are inserted through the GelPort® at 1 and 5 o’clock, respectively. After establishing pneumoperitoneum at 15 mmHg with the AirSeal® System (ConMed, Utica, NY, United States), three 8 mm robotic ports are inserted along a straight line parallel to the midline, 2-3 cm lateral to it on the side of the kidney being removed. The first port is placed 2 cm below the costal margin, with each subsequent robotic port spaced 8 cm apart (Figure 1). Once the robot is docked and instruments are inserted in the abdomen, pneumoperitoneum is reduced to 8 mmHg and maintained at that level for the rest of the procedure.

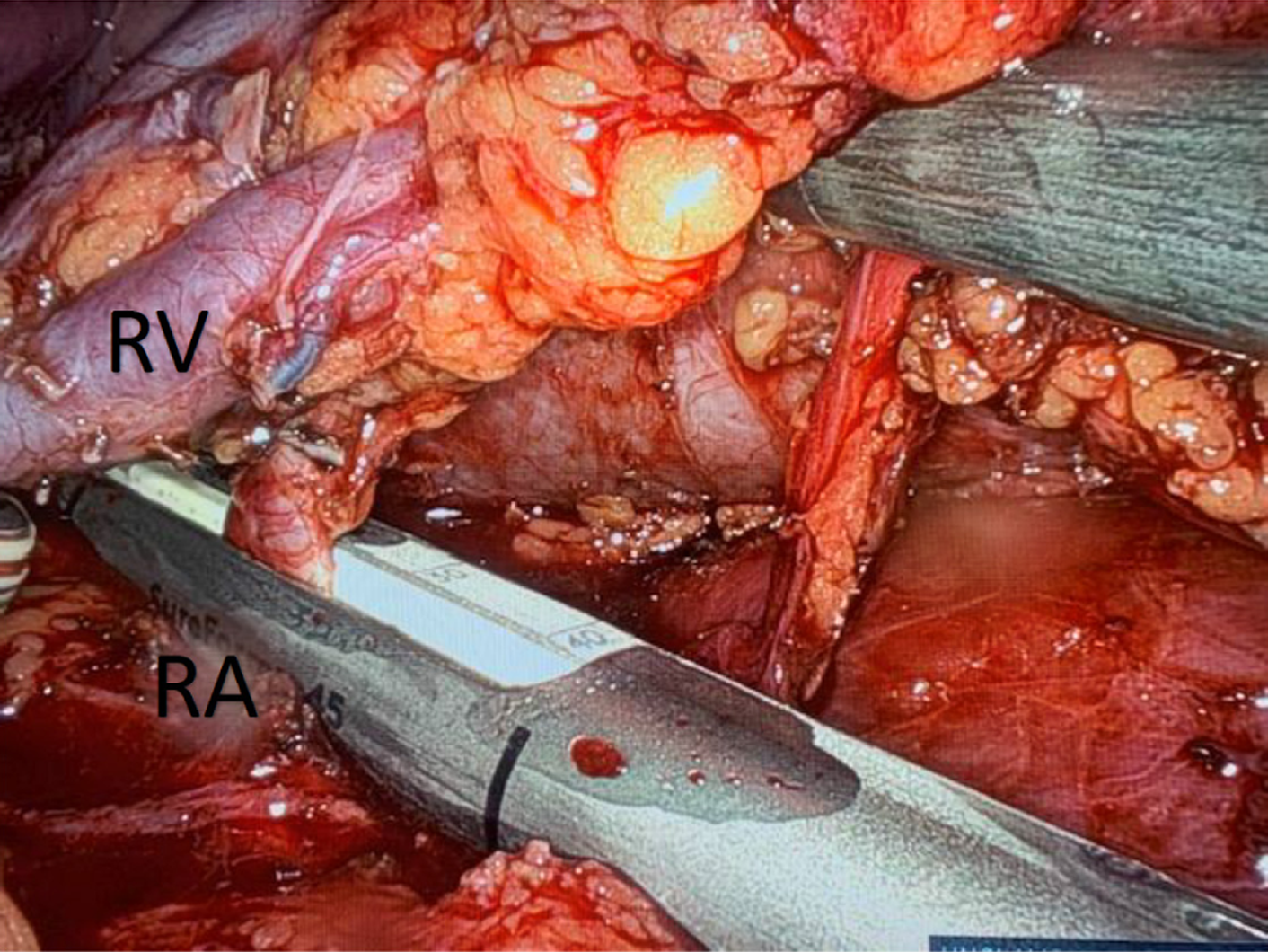

The surgery begins with the mobilisation of the colon to expose the kidney. For this part of the procedure, we use the monopolar robotic scissors for dissection. For the rest of the procedure, we use mainly the Vessel Sealer™ (Intuitive Surgical, Sunnyvale, CA, United States) to dissect, seal, and cut lymphatic and blood vessels (gonadal vein, adrenal vein, lumbar veins). For left-sided kidneys, the gonadal vein is identified distally and followed to its confluence with the renal vein, where it is divided. The ureter is identified and lifted off the psoas muscle. A clear plane is developed between the ureter and psoas muscle for its entire length (from the hilum to the crossing with the iliac artery). The adrenal gland is dissected off the upper pole of the kidney, and the adrenal vein is transected. We continue the dissection until the upper pole is free. Next, we free the back side of the kidney from its surrounding fat. The final part of the dissection involves freeing the renal vessels from surrounding fat and lymphatics. At this stage, we will transect the lumbar veins, if present. The ureter is transected at its crossing with the iliac artery with robotic scissors. The ureteric stump is secured with a Hem-o-lok® clip (Teleflex Medical, Research Triangle Park, NC, United States). The renal artery and vein are stapled using the 8 mm, 30° SureForm™ robotic stapler (Intuitive Surgical, Sunnyvale, CA, United States) (Figure 2).

Once the kidney is free, it is extracted through the GelPort® with the assistance of laparoscopic forceps. The kidney is removed from the abdomen, placed in ice, and perfused by a bedside surgical assistant. Pneumoperitoneum is lowered at 4 mmHg, haemostasis is ensured at the renal bed, and the wound is closed in layers - peritoneum, aponeurosis, subcutaneous tissue, and skin - with absorbable sutures and without drains.

HALDN laparoscopic donor nephrectomy: Eight different surgeons are performing the HALDN operations in our department. Seven performed trans-peritoneal and one retro-peritoneal approach. The donor is placed in a lateral position with the table in a minimally or moderately broken position, depending on the donor’s body habitus and the surgeon’s preference. A 6-8 cm midline incision is made. This can be supra- or infra-umbilical, transverse, or longitudinal. GelPort® is inserted through the incision, and pneumoperitoneum is established at 10-15 mmHg using the AirSeal® system. Two additional 10-12 mm laparoscopic ports are inserted on the side of the kidney to be removed. An additional 5 mm port is occasionally inserted for retracting the kidney or liver. For kidney dissection and vessel ligation (adrenal, gonadal, lumbar veins) we use the Harmonic® scalpel (Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Cincinnati, OH, United States) or the Thunderbeat® (Olympus Medical Systems Corp., Tokyo, Japan).

The surgery begins with the mobilisation of the colon to expose the kidney. For left-sided kidneys, the gonadal vein is identified distally and followed to its confluence with the renal vein, where it is divided. The ureter is identified and lifted off the psoas muscle. A clear plane is developed between the ureter and psoas muscle for all its length (hilum to crossing with the iliac artery). The adrenal gland is dissected off the upper pole of the kidney and adrenal vein is transected. We continue the dissection until the upper pole is free. Next, we free the back side of the kidney from its surrounding fat. The final part of the dissection involves freeing the renal vessels from surrounding fat and lymphatics. At this stage, we will transect the lumbar veins, if present. The ureter is transected at its crossing with the iliac artery with scissors. The ureteric stump is secured with a Hem-o-lok® clip (Teleflex Medical, Research Triangle Park, NC, United States). Renal vessels are divided using the Echelon Flex™ 35 mm vascular stapler (Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Cincinnati, OH, United States). The kidney is removed from the abdomen, placed in ice, and perfused by the bedside surgical assistant. Haemostasis at the renal bed is ensured. All ports are closed using an EndoClose™ (Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN, United States), with the peritoneum, fascial, and skin layers secured with absorbable sutures.

Primary: (1) Primary warm ischaemic time (WIT) - minutes: Time from stapling of the renal artery until kidney perfusion with cold preservation solution; (2) Duration of the operation - minutes: The time from when a patient enters the theatre intubated until the patient reaches recovery. For the robotic procedures, console time is defined as the period during which the surgeon is actively operating the robotic surgical system. Console time was retrieved from my intuitive (Intuitive Surgical, Sunnyvale, CA, United States) mobile phone application; (3) Pain scores on days 1, 2, and 3 post-operatively: As documented by nursing staff based on the revised fascial pain intensity scale[16]; (4) Duration of patient-controlled analgesia post-operatively - days; post-operative hospital stay - days; (5) Postoperative complications - Clavien-Dindo classification[17]; (6) Re-admissions and re-operations at any time following the index hospitalization; and (7) Donor creatinine level on day 30 and day 365 postoperatively in μmol/L.

Secondary: Creatinine levels of the recipient at 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months postoperatively in μmol/L. Paediatric recipients were excluded from the analysis of the secondary outcomes. Additionally, delayed graft function was defined as the need for dialysis within the first week after the kidney transplantation.

All data were retrieved from the electronic system of our hospital. Recipient data from kidneys directed to other hospitals were retrieved following communication with the respective centers. Qualitative parameters were described using numbers and percentages and compared using χ2 analysis. Based on the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, all quantitative parameters were distributed normally and were thus described using mean ± SD and compared using the parametric t-test. For all eligible 493 donor nephrectomies a case-control analysis was performed adjusting for the following independent variables (with respective tolerance): Sex (exact match), laterality of the operation (exact match), number of kidney arteries (exact match), age (3 years), BMI (3 kg/m2), and history of previous abdominal surgeries (exact match). All statistical analyses were conducted using the SPSS version 29.

Of 493 donor nephrectomies were conducted in total during the study period (Table 1); 415 HALDN (84.2%) and 78 RALDN (15.8%). Based on the tolerances used in the case-control matching analysis, 70 HALDN cases were matched with 70 RALDN, creating the study cohort of 140 donor nephrectomies. Of 8 RALDN remained unmatched and were excluded from the study.

| HALDN (n = 70) | RALDN (n = 70) | P value | |

| Male | 34 (48.6) | 34 (48.6) | 1 |

| Left | 68 (97.1) | 68 (97.1) | 1 |

| Number of arteries 1 | 61 (87.1) | 61 (87.1) | 1 |

| More than 1 | 9 (12.9) | 9 (12.9) | |

| Age (mean ± SD) | 43.19 ± 10.29 | 43.69 ± 10.14 | 0.75 |

| BMI (mean ± SD) | 26.36 ± 3.48 | 26.03 ± 3.28 | 0.57 |

| History of previous abdominal surgeries | 11 (15.7) | 11 (15.7) | 1 |

Primary outcomes for the RALDN and HALDN are shown in Table 2. There were 9 (12.9%) post-operative complications in the HALDN group: Four (5.7%) wound infections requiring antibiotics, one (1.5%) infection of unknown origin, one (1.5%) case of omentitis, one (1.5%) intra-abdominal sepsis, one (1.5%) incisional hernia and one (1.5%) donor with a keloid scar. There were 8 (11.4%) post-operative complications in the RALDN group: Two (2.9%) wound infections requiring antibiotics, two (2.9%) urine infections, one (1.5%) surgical emphysema requiring antibiotics, one (1.5%) case of persistent microscopic haematuria requiring flexible cystoscopy, one (1.5%) case of wound re-exploration for a palpable polydioxanone suture stitch that protruded through the wound and one (1.5%) incisional hernia.

| HALDN (n = 70) | RALDN (n = 70) | P value | |

| Duration of operation in minutes | 247.14 ± 109.0 | 254.57 ± 108.2 | 0.62 |

| Warm ischaemic time in minutes | 2.76 ± 1.3 | 3.53 ± 1.4 | < 0.001 |

| Pain score | |||

| Day 1 | 1.84 ± 0.97 | 2.04 ± 0.84 | 0.20 |

| Day 2 | 1.63 ± 0.89 | 1.61 ± 0.84 | 0.92 |

| Day 3 | 0.93 ± 0.79 | 0.94 ± 0.68 | 0.91 |

| Post-operative day at which PCA was down | 2.39 ± 0.71 | 2.21 ± 0.76 | 0.17 |

| Length of hospital stay | 3.17 ± 1.15 | 4.21 ± 1.75 | < 0.001 |

| Complication rate | 9 (12.9) | 9 (12.9) | |

| Clavien-Dindo II | 7 (10) | 5 (7.1) | |

| Clavien-Dindo IIIa | 0 (0) | 1 (1.4) | |

| Clavien-Dindo IIIb | 2 (2.9) | 3 (4.3) | 1 |

| Readmissions | 7 (10) | 5 (7.1) | |

| Clavien-Dindo II | 5 (7.1) | 3 (4.2) | |

| Clavien-Dindo IIIb | 2 (2.9) | 2 (2.9) | 0.55 |

| Reoperations | 2 (2.9) | 2 (2.9) | |

| Intra-abdominal sepsis | 1 (1.4) | 0 (0) | |

| Incisional hernia | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.4) | |

| Wound re-exploration | 0 (0) | 1 (1.4) | 1 |

| Creatinine (μmol/L) | |||

| Day 30 | 114.87 ± 26.1 | 110.89 ± 24.9 | 0.37 |

| Day 365 | 111.81 ± 28.7 | 107.45 ± 18.8 | 0.37 |

There was one (1.5%) intraoperative complication in the RALDN group. This was a vascular stapler misfire on the renal artery that led to massive bleeding. It occurred on the last (15th case) of the pilot phase. At that time, a laparoscopic stapler was used that was controlled by the bedside surgical assistant. The case was converted into open surgery, the bleeding was controlled, the kidney was retrieved with fifteen minutes of WIT, flushed with cold preservation solution on the back table as per standard practice, and implanted, with both donor and recipient being discharged with no further complications. The recipient had primary graft function. Following this, the program was paused, and an independent committee conducted an investigation. The program restarted with the following modifications: The emergency robot undock procedure is practiced before each case. A rescue suture and a laparotomy set are available. The vascular stapler was switched from laparoscopic to robotic. Every case is recorded. Following the above case, no other conversion to open surgery has occurred.

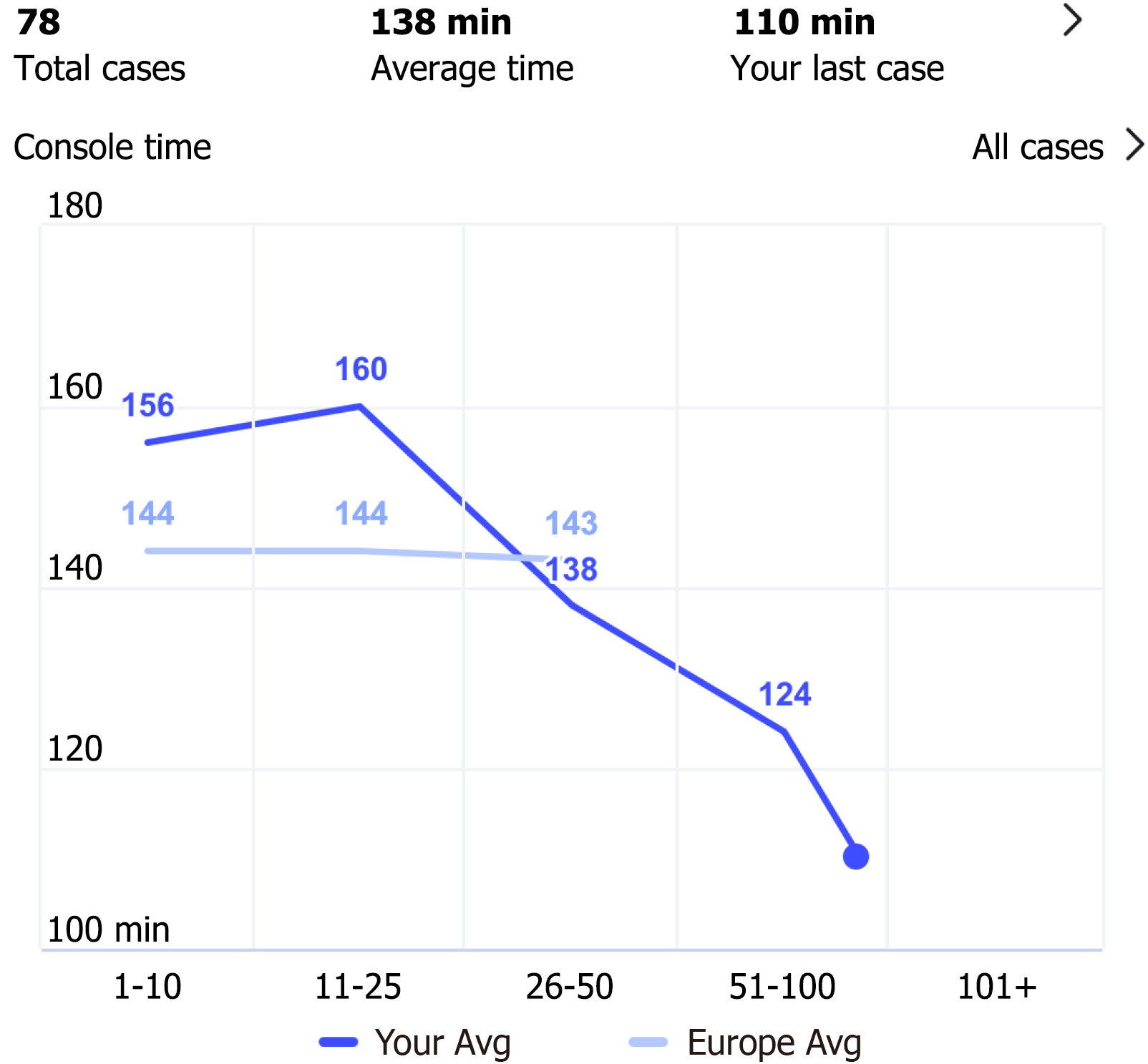

Figure 3 derived from my intuitive (Intuitive Surgical, Sunnyvale, CA, United States), illustrates the trend of console time. Notably, as the caseload increases, there is a significant decrease in console time. Interestingly, while in the initial phases of our program, the mean console time was longer than the European average, it is now significantly shorter.

There was no difference in recipient creatinine levels between the two groups at three, six, and twelve months post-operatively. Additionally, no cases of delayed graft function were observed in either group (Table 3).

| Recipient creatinine (μmol/L) | HALDN (n = 70) | RALDN (n = 70) | P value |

| 3 months | 111.8 ± 34.7 | 119.4 ± 33.1 | 0.24 |

| 6 months | 113.2 ± 31.3 | 115.7 ± 35.4 | 0.76 |

| 1 year | 108.8 ± 25.5 | 118.8 ± 37.1 | 0.18 |

In this inaugural national cohort, we demonstrate that RALDN and HALDN achieve equivalent safety and efficacy outcomes. Specifically, there was no significant difference between the two groups in complication rates (12.9%), readmission to the hospital, reoperation, pain scores, or the need for postoperative analgesia. The overall operative time was similar between the two techniques, although the surgeon performing the robotic procedure for a number of those cases was going through the learning curve. Furthermore, the RALDN console time was significantly reduced as the surgeon gained more experience. WIT was significantly longer in the RALDN group (3.53 minutes) compared to the HALDN group (2.76 minutes, P < 0.001). The slightly longer WIT observed in robotic donor nephrectomy is mainly attributable to workflow differences: Unlike the HALDN approach, where the graft is immediately extracted through the gel port by the primary surgeon, robotic retrieval requires sequential withdrawal and reloading of the robotic stapler, use of a grasping forceps to guide the kidney towards the gel port, and subsequent extraction through the gel port by the bedside assistant. In addition, many robotic cases were performed early in the learning curve, and graft retrieval in robotic procedures is inherently performed via the gel port by the bedside assistant rather than directly by the primary surgeon, which could have modestly prolonged WIT. Importantly, no cases of delayed graft function occurred in either group, and recipient creatinine at 3 months, 6 months, and 12 months showed no significant differences. Thus, the modest difference in WIT did not translate into adverse effects on graft functional recovery. The RALDN group had a significantly longer average hospital stay, approximately 1 day longer.

The comparable outcomes observed between RALDN and HALDN in this study likely reflect several converging factors. Both techniques are minimally invasive and share similar principles, so large differences in endpoints were not anticipated. Our HALDN programme is well established, supported by decades of surgical experience, a high donor nephrectomy caseload, an enhanced recovery protocol, and surgeons well past their learning curves. In contrast, our RALDN programme - currently the only established programme among United Kingdom transplant centers - was recently introduced, with the lead surgeon starting without prior robotic experience and many early cases performed at the beginning of the learning curve. Although a few other United Kingdom centers have started RALDN, they remain in their early phases. Case volume for RALDN is limited, both because living donor surgery is inherently lower volume than other robotic disciplines, such as surgical oncology, and because multiple specialties compete for access to the robot. Unlike oncology, where surgeons can begin with simpler robotic procedures and progress to more complex cases, transplant surgeons can only apply robotics to technically demanding operations such as donor nephrectomy and kidney implantation, with deceased-donor cases adding further logistical challenges that have restricted their adoption worldwide. Despite these constraints, our center has established a successful RALDN programme, offering the procedure to all eligible donors when robot and surgeon availability permit, while training two additional transplant surgeons in the technique. Notably, our RALDN work has also laid the foundation for a robotic-assisted kidney transplant programme, currently running as a pilot study with ten completed cases. Over time, RALDN outcomes have improved, with a significant reduction in console time indicating a steep learning trajectory. As experience grows, we expect the full benefits of the robotic platform to materialize, a view supported by meta-analysis evidence showing that when surgeon experience is equivalent, RALDN can achieve superior results in conversion rates, operative time, complications, and hospital stay compared with laparoscopic-assisted nephrectomy[18].

Robotic surgery is often associated with longer operative times and higher overall costs, setting the cost-effectiveness of robotic surgery into question[8,19]. A recent study revealed that, over time, robotic procedures are associated with a more significant reduction of post-operative complications and a decrease in the length of stay[20]. Nevertheless, the discrepancy in costs between laparoscopic and robotic-assisted surgery has widened over time[20]. In this study, we did not compare the cost differences between the two procedures. However, since we started our program, new instruments have been added to the robotic platform, such as the Vessel Sealer™ and the robotic stapler. These have resulted in decreased surgical time but have increased the overall cost of the procedure. Future studies should aim to assess whether these long-term benefits can offset the increasing costs, thereby providing a clearer understanding of the value proposition of robotic-assisted surgery compared to laparoscopic techniques.

The RALDN program provides a unique teaching opportunity, offering a pathway to develop robotic expertise within the department, with other surgeons currently being trained in RALDNs and our pilot robotic-assisted kidney transplant program[21]. Furthermore, the robotic platform offers enhanced ergonomics for surgeons, offering a seated position, reducing fatigue during long operations, and alleviating the strain associated with awkward angles and prolonged hand positioning during laparoscopic surgery, such as robotic kidney transplantation for recipients[22,23]. Over the long term, these ergonomic advantages allow surgeons to maintain their performance and stamina, enabling them to handle more cases over their careers, which translates into better allocation of personnel and improved departmental efficiency. Notably, 1 in 5 laparoscopic surgeons consider early retirement due to work-related musculoskeletal pain[24]. For all these reasons, and even while the RALDN currently incurs higher costs, we believe that investing in RALDN is justified, as it not only enhances the department’s capabilities but also positions the institution at the forefront of innovative surgical techniques.

We compared our results with four other studies in the literature, which compare RALDN with laparoscopic-assisted donor nephrectomies. Notably, the literature concurs that RALDN is associated with longer WIT[10,13] but this does not affect the overall duration of the operation[11,12]. The literature also suggests that despite the longer WIT in RALDN, this does not affect the long-term graft function of recipients, with comparable long-term creatinine values[11,13]. In contrast, our study’s observation of a longer hospital stay for RALDN contradicts the rest of the literature, which supports that RALDN is associated with shorter hospital stays for donors[10,11,13]. This discrepancy could be due to differences in hospital discharge protocols. Despite this, both our study and others consistently show that RALDN achieves excellent post-operative recovery outcomes, with no significant differences in pain scores or complication rates compared to HALDN. In fact, pain scores and the need for analgesics are reported to be improved in the RALDN group in the literature[12-14]. Finally, the literature affirms that both surgical techniques are equally safe for donors since all studies report comparable post-operative complication rates, re-admissions, and re-operations[11-14]. The short- and long-term creatinine levels of the donors are also reported to be comparable. In fact, one study reports the donor creatinine at discharge to be significantly lower in the RALDN group[11].

One of the main limitations of our study is its retrospective design, which inherently introduces selection bias. However, we mitigated confounding factors by employing a case-control matching analysis, ensuring that the two groups were comparable in terms of key independent variables. Some residual confounders may still exist. One of them is certainly the fact that one surgeon performs the RALDNs, while the HALDNs are performed by multiple surgeons of different levels of experience and with variations regarding their surgical approach to the operation. Additionally, the selection of patients for RALDNs and HALDNs during the early phase of the study was influenced by multiple logistical and donor-related factors, which may have introduced a degree of bias in terms of patient allocation. Another limitation is that we relied on single-center data, which may limit our findings’ generalizability to other centers or populations with different healthcare practices and expertise, while ensuring consistency in surgical practice. Lastly, long-term follow-up data on donor outcomes, particularly graft function beyond one year, were not comprehensively analyzed, leaving a gap in our understanding of how these techniques compare over extended periods. As the safety of the RALDN procedure is well-established in the literature, we believe future research should focus on investigating trends in surgical outcomes as the robotic surgical experience grows. Additionally, cost-effectiveness analyses are needed to examine how the cost differences between laparoscopic and RALDN approaches evolve over time and whether improvements in surgical outcomes can justify the higher costs[25].

This is the first study for robotic donor nephrectomy coming out of the United Kingdom National Health Service. It demonstrated that RALDN is equally safe and effective as the gold standard HALDN laparoscopic donor nephrectomy technique. Furthermore, it proved the feasibility of starting and establishing the procedure in transplant centers with no previous experience and no regular exposure to the robot. As the use of robotic platforms is spreading to transplant centers around the world and experience grows, we expect future studies to prove its superiority in terms of outcomes in comparison to laparoscopic surgery.

We would like to express our deepest gratitude to Leigh Harkerss, Anita Copley, Lisa Silas, Miri Vutabwarova, Kristi Whitelock, Amy Shipperley, and Pinky Chiu, for all their hard work as our living donor coordinator team. In addition, we would like to thank Health Education England, Intuitive Surgical Operations LTD, Guy’s Charity, and Chiesi Limited for providing support for developing our RALDN pathway.

| 1. | Nemati E, Einollahi B, Lesan Pezeshki M, Porfarziani V, Fattahi MR. Does kidney transplantation with deceased or living donor affect graft survival? Nephrourol Mon. 2014;6:e12182. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Global Observatory on Donation and Transplantation. Countkidney. [cited 30 June 2025]. Available from: https://www.transplant-observatory.org/countkidney/. |

| 3. | Kovesdy CP. Epidemiology of chronic kidney disease: an update 2022. Kidney Int Suppl (2011). 2022;12:7-11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 272] [Cited by in RCA: 1685] [Article Influence: 421.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Maggiore U, Oberbauer R, Pascual J, Viklicky O, Dudley C, Budde K, Sorensen SS, Hazzan M, Klinger M, Abramowicz D; ERA-EDTA-DESCARTES Working Group. Strategies to increase the donor pool and access to kidney transplantation: an international perspective. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015;30:217-222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Andersen MH, Mathisen L, Oyen O, Edwin B, Digernes R, Kvarstein G, Tønnessen TI, Wahl AK, Hanestad BR, Fosse E. Postoperative pain and convalescence in living kidney donors-laparoscopic versus open donor nephrectomy: a randomized study. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:1438-1443. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 88] [Article Influence: 4.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Darzi SA, Munz Y. The impact of minimally invasive surgical techniques. Annu Rev Med. 2004;55:223-237. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Roh HF, Nam SH, Kim JM. Robot-assisted laparoscopic surgery versus conventional laparoscopic surgery in randomized controlled trials: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0191628. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 10.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Kawka M, Fong Y, Gall TMH. Laparoscopic versus robotic abdominal and pelvic surgery: a systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Surg Endosc. 2023;37:6672-6681. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 14.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Lai TJ, Roxburgh C, Boyd KA, Bouttell J. Clinical effectiveness of robotic versus laparoscopic and open surgery: an overview of systematic reviews. BMJ Open. 2024;14:e076750. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Windisch OL, Matter M, Pascual M, Sun P, Benamran D, Bühler L, Iselin CE. Robotic versus hand-assisted laparoscopic living donor nephrectomy: comparison of two minimally invasive techniques in kidney transplantation. J Robot Surg. 2022;16:1471-1481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Papa S, Popovic A, Loerzel S, Iskhagi S, Gallay B, Leggat J, Saidi R, Hod Dvorai R, Shahbazov R. Laparoscopic to robotic living donor nephrectomy: Is it time to change surgical technique? Int J Med Robot. 2023;19:e2550. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Zeuschner P, Hennig L, Peters R, Saar M, Linxweiler J, Siemer S, Magheli A, Kramer J, Liefeldt L, Budde K, Schlomm T, Stöckle M, Friedersdorff F. Robot-Assisted versus Laparoscopic Donor Nephrectomy: A Comparison of 250 Cases. J Clin Med. 2020;9:1610. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Bhattu AS, Ganpule A, Sabnis RB, Murali V, Mishra S, Desai M. Robot-Assisted Laparoscopic Donor Nephrectomy vs Standard Laparoscopic Donor Nephrectomy: A Prospective Randomized Comparative Study. J Endourol. 2015;29:1334-1340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 4.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wang H, Chen R, Li T, Peng L. Robot-assisted laparoscopic vs laparoscopic donor nephrectomy in renal transplantation: A meta-analysis. Clin Transplant. 2019;33:e13451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Lancet. 2007;370:1453-1457. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6805] [Cited by in RCA: 13645] [Article Influence: 718.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (4)] |

| 16. | Wood C, von Baeyer CL, Falinower S, Moyse D, Annequin D, Legout V. Electronic and paper versions of a faces pain intensity scale: concordance and preference in hospitalized children. BMC Pediatr. 2011;11:87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Clavien PA, Barkun J, de Oliveira ML, Vauthey JN, Dindo D, Schulick RD, de Santibañes E, Pekolj J, Slankamenac K, Bassi C, Graf R, Vonlanthen R, Padbury R, Cameron JL, Makuuchi M. The Clavien-Dindo classification of surgical complications: five-year experience. Ann Surg. 2009;250:187-196. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6210] [Cited by in RCA: 9217] [Article Influence: 542.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 18. | Khajeh E, Nikbakhsh R, Ramouz A, Majlesara A, Golriz M, Müller-Stich BP, Nickel F, Morath C, Zeier M, Mehrabi A. Robot-assisted versus laparoscopic living donor nephrectomy: superior outcomes after completion of the learning curve. J Robot Surg. 2023;17:2513-2526. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Higgins RM, Frelich MJ, Bosler ME, Gould JC. Cost analysis of robotic versus laparoscopic general surgery procedures. Surg Endosc. 2017;31:185-192. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 82] [Cited by in RCA: 113] [Article Influence: 11.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Ng AP, Sanaiha Y, Bakhtiyar SS, Ebrahimian S, Branche C, Benharash P. National analysis of cost disparities in robotic-assisted versus laparoscopic abdominal operations. Surgery. 2023;173:1340-1345. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 66] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Rahimi AM, Uluç E, Hardon SF, Bonjer HJ, van der Peet DL, Daams F. Training in robotic-assisted surgery: a systematic review of training modalities and objective and subjective assessment methods. Surg Endosc. 2024;38:3547-3555. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Dalager T, Jensen PT, Eriksen JR, Jakobsen HL, Mogensen O, Søgaard K. Surgeons' posture and muscle strain during laparoscopic and robotic surgery. Br J Surg. 2020;107:756-766. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 64] [Article Influence: 10.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Berguer R, Smith W. An ergonomic comparison of robotic and laparoscopic technique: the influence of surgeon experience and task complexity. J Surg Res. 2006;134:87-92. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 106] [Cited by in RCA: 118] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Dixon F, Vitish-Sharma P, Khanna A, Keeler BD. Work-related musculoskeletal pain and discomfort in laparoscopic surgeons: an international multispecialty survey. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2023;105:734-738. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Christou CD, Athanasiadou EC, Tooulias AI, Tzamalis A, Tsoulfas G. The process of estimating the cost of surgery: Providing a practical framework for surgeons. Int J Health Plann Manage. 2022;37:1926-1940. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/