INTRODUCTION

In the United States, diabetes mellitus (DM) continues to be one of the most consequential chronic diseases for overall morbidity and a leading cause of death[1].

The overall prevalence of patients with DM has increased over time, the absolute number of patients with DM has also continued to increase[2]. According to a 2023 study, there was an estimated prevalence of 7.6% of the total United States population (25.5 million patients) and 9.6% of the adult population in the United States in 2022, with an estimated direct medical cost of 307 billion United States dollars[2]. Type 1 DM (T1DM) is characterized by DM typically resulting from autoimmune-mediated damage to beta cells, leading to decreased or absent insulin production[3]. The incident rates of T1DM have also been shown to increase over time, estimated at approximately 64000 annually for individuals aged 0-64 years in the United States[4]. The results from this database study of commercially insured individuals in the United States also demonstrated that adult-onset T1DM may be more prevalent than previously believed, accounting for 18.6 per 100000 persons aged 20-64 years, compared to 34.3 per 100000 persons for ages 0-19 years[4]. Considering the total number of patients in each age group, there were 19174 new cases in the 20-64 years cohort compared to 13302 new cases in the 0-19 years cohort for the period under study. Appropriately classifying adults presenting with T1DM is often challenging due to a multitude of factors, including the high background prevalence of type 2 DM (T2DM) in this population, as well as the general lack of awareness that the onset of T1DM is not restricted to children[5]. The pathophysiology of T2DM is distinct, primarily due to genetic causes of chronic inflammation and insulin resistance, culminating in beta-cell exhaustion[3]. This distinction between adult-onset T1DM and T2DM is essential, as there are clinically significant differences in metabolic outcomes, as well as rates of progression[6].

Compared to the first pancreas transplantation (PT) performed on December 17, 1966, by W. Kelly and R. Lillehei at the University of Minnesota, the field of PT has had greatly improved outcomes owing to improvements in immunosuppressive therapy as well as surgical technique[7]. Simultaneous pancreas-kidney (SPK) transplantation (where both kidney and pancreas organs are procured from the same deceased donor) is now considered the treatment of choice for patients with T1DM and related end-stage kidney disease for appropriate candidates[8]. The recipient of that first segmental graft PT as part of a SPK in 1966 did not require exogenous insulin for six days following the transplant; however they soon developed graft pancreatitis thought to be related to duct ligation and required removal of both the pancreas graft and rejected kidney, and subsequently died from a pulmonary embolism 13 days after pancreas graft removal[7]. With time, surgical technique changed considerably to being whole organ vs a prior segmental graft. Duct management also evolved from being cutaneous duodenostomy vs prior duct ligation, with the second PT and Lillehei as the lead surgeon, though it was also done in the setting of SPK[7]. The original technique of pancreas graft exocrine drainage was to the bladder, leading to several associated complications of metabolic acidosis, UTI, and reflux pancreatitis from urinary retention, to name a few[9]. Enteric drainage of the pancreas graft was first performed in 1981 and became widely utilized in the latter part of the 1990s alongside increased utilization of anti-thymocyte globulin for induction[10].

There have been recent changes to the pancreas allocation system to better align with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services' Final Rule requirements, which prohibit allocating organs based on the candidate’s place of residence or listing while also placing a limit on cold ischemia time[11]. Compared to the prior allocation policy, this new allocation system using 250 nautical miles organ distribution scenario predicted increased kidney-pancreas transplants for female, non-Latino, Black, and highly sensitized to maximize equity and efficiency in organ allocation[11].

INDICATIONS FOR PANCREAS TRANSPLANTATION

The indications for PT have evolved since its inception, although its use for patients with T1DM predominates, albeit with declining absolute numbers, with approximately 607 transplants in 2023, down from 893 in 2012[12]. On the other hand, use of PT in T2DM has expanded in the recent years, with approximately 232 recipients in 2023 compared to 69 in 2012. Consideration for SPK is indicated for select medically appropriate patients with insulin-dependent DM who are concurrently eligible for kidney transplantation due to an estimated glomerular filtration rate of less than or equal to 20 mL/minutes or on dialysis[13]. Stable patients with a functioning kidney transplant and with insulin-dependent DM (id-DM), can be considered for PT after kidney transplant (PAK) to achieve independence from exogenous insulin and improved quality of life[14,15]. Finally, there is the indication for PT alone (PTA), usually for severe complications of id-DM, such as frequent and severe hypoglycemia (especially with hypoglycemia unawareness) or ketoacidosis[16]. Prior to 2019, the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) criteria for PT listing required that potential candidates have an ongoing need for exogenous insulin with either an absolute deficiency in endogenous insulin demonstrated by a blood C-peptide less than 2 ng/mL or if C-peptide is greater than 2 ng/mL and concomitant body mass index (BMI) less than 28 kg/m2[9]. However, in 2019, UNOS removed the C peptide and BMI requirements, thereby expanding eligibility and allowing more patients with T2DM to qualify for PT[17].

BENEFITS OF PANCREAS TRANSPLANT: PATIENT AND GRAFT SURVIVAL

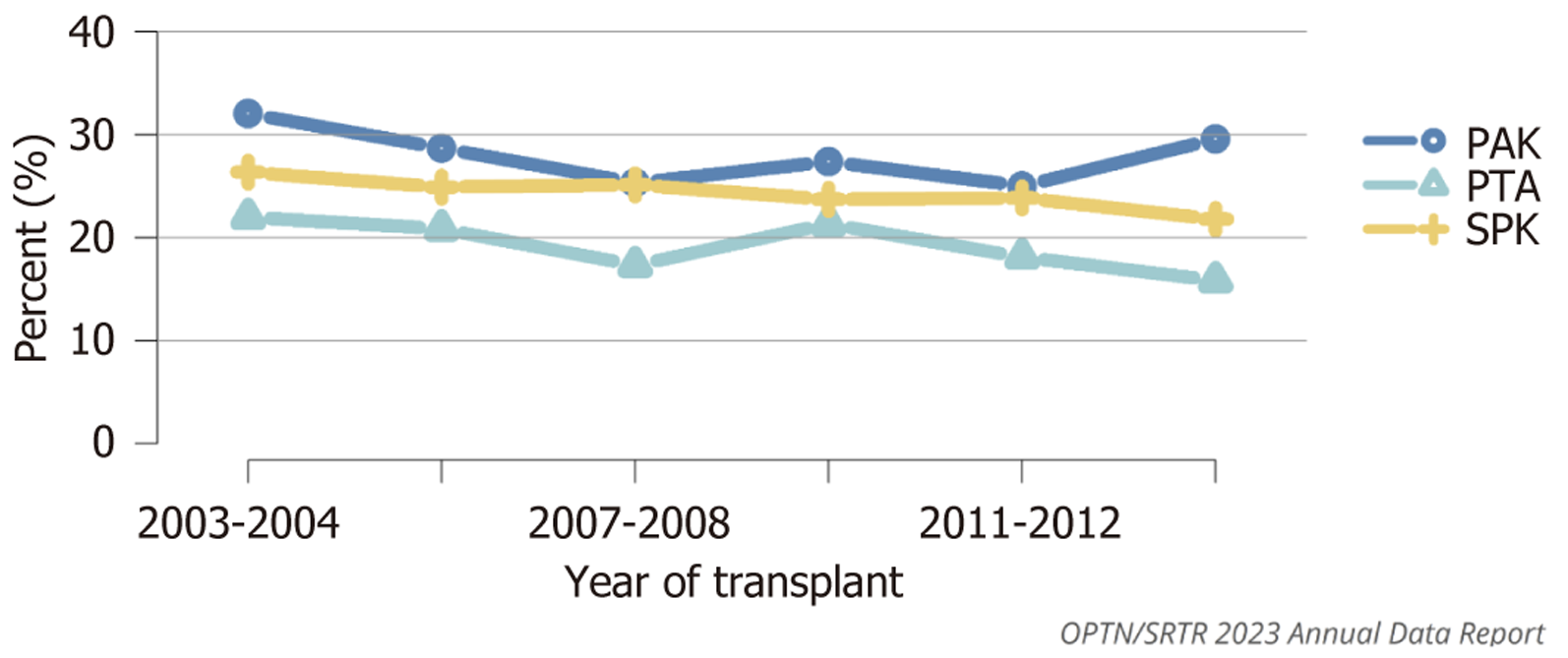

To this day, PT remains the treatment of choice to achieve sustained insulin independence for patients with T1DM[10,18]. Patients with functional pancreas allografts report better glucose control than with insulin, and improved quality of life as well as better overall health scores when compared against those with failed grafts[14]. SPK transplant affords an 10-year patient survival rate of 78% similar to living donor kidney alone transplant and far superior to the survival of deceased-donor kidney-alone transplant recipients, but PAK affords a lower 10-year patient survival rate of 70.4% (Figure 1)[9,19-21].

Figure 1 Patient death at 10 years among adult pancreas transplant recipients.

Outcomes are computed using unadjusted Kaplan-Meier methods. Transplant recipients are followed from date of transplant to the earlier of death or 10 years posttransplant. Only first pancreas transplant is considered. PAK recipients without a record of previous kidney or kidney-pancreas transplant are reclassified as PTA. All time points are 2-year periods. PAK: Pancreas after kidney; PTA: Pancreas transplant alone; SPK: Simultaneous pancreas-kidney. Source: Figure PA70, OPTN/SRTR 2023 Annual Data Report. HHS/HRSA; 2025. Accessed July 28, 2025. https://srtr.transplant.hrsa.gov/annualdatareports.

MAJOR CHALLENGES: DECREASE IN THE NUMBER OF PANCREAS TRANSPLANTS DUE TO CORONAVIRUS DISEASE 2019, ORGAN AVAILABILITY, AND IMPROVEMENTS IN DIABETES CARE, AMONG OTHERS

The coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic necessitated considerations in the realm of PT. The overall number of PT in the United States saw a slight decline in 2023 to 915 from 918 the year prior, with the number of PAK of 36 being the lowest of the previous decade[12]. The decline in PT is multifactorial, given both the low amount of usable deceased donor pancreas recovered and can also be partially attributed to improvements in non-surgical DM management that obviate the need for PT and its associated complications, both surgical and those related to chronic immunosuppression[14,22].

CONTRAINDICATIONS: ABSOLUTE AND RELATIVE

As with kidney transplants, there are risks inherent in PT that have been discussed thus far, and there are contraindications, both relative and absolute, that must be considered. Relative contraindications to PT include history of stroke with persistent neurologic deficits, ongoing abuse of drugs and/or alcohol, active hepatitis infection, extensive vascular disease, particularly in the aortoiliac region, and a total daily insulin requirement exceeding 1.5 units/kg, which would make it unlikely to achieve insulin independence with PT[16]. Absolute contraindications to PT are similar to those of other elective solid organ transplantation, including active infection or peptic ulcer disease, significant uncontrolled psychiatric history, active or incurable malignancy (excluding localized skin cancers), high cardiovascular risk for mortality (e.g., significant uncorrectable coronary artery disease, severe pulmonary hypertension advanced heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, and/or recent myocardial infarction in last 6 months) and finally if patient is otherwise unable to tolerate the surgery and immunosuppression[16].

IMPACT OF RECIPIENT BMI ON PATIENT AND GRAFT SURVIVAL

A BMI has been established as a significant risk factor associated with the incidence of DM; however, BMI remains a controversial predictor of mortality for those with DM[23]. The controversy is rooted in inconsistent studies with conflicting results. For example, the results of a 2012 study of 2625 participants were suggestive of an obesity paradox where patients with a higher BMI of overweight or obese at the time of DM diagnosis were conferred a lower mortality risk than those who were of normal BMI at the time of DM diagnosis[24]. However, the results of the larger 2014 study of 8970 participants observed no evidence of lower mortality among patients with DM who were overweight or obese at diagnosis compared to their normal weight cohort[25]. The data on the association between BMI and PT risks is more consistent. A 2015 retrospective study found significant associations between recipient BMI and important clinical outcomes[26]. This study analyzed the data available from all PT recipients in the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients between 1987 and 2011 and found increasing recipient BMI as an independent predictor of pancreatic graft loss and patient death in the short term (90 days), particularly for BMI greater than 35 kg/m2. Additionally, this study found that a BMI less than 18.5 kg/m2 was an independent predictor for long-term (90-day to 5-year) death, while a BMI greater than 30 kg/m2 predicted a higher risk of long-term (90-day to 5-year) graft failure.

EFFECT OF SPK ON DIABETES ASSOCIATED END-ORGAN COMPLICATIONS- AN INTEGRATIVE PERSPECTIVE

Effect on peripheral vascular disease

Patients who undergo SPK transplantation tend to have a lower burden of peripheral vascular complications compared to those who receive a kidney transplant alone (KTA). These complications include ischemic ulceration, revascularization procedures, and amputations, with the latter two showing significant reductions in the SPK group[27]. These findings are primarily attributed to improved glycemic control and better lipid profiles, resulting from the restoration of endogenous insulin production after pancreas transplantation.

However, not all studies are consistent. One study reported that pancreas transplantation did not significantly decrease the incidence of peripheral vascular complications when compared to kidney alone transplantation over the study's follow-up period[28]. In that study, the only independent predictor of the post-transplant peripheral arterial disease events was a history of a preexisting peripheral vascular disease. It is important to note that this study had a relatively short follow-up duration of 45 months, which may not have been sufficient to capture the full vascular benefit of PT.

Effect on diabetic retinopathy

There have been concerns that abrupt glucose normalization following SPK may lead to worsening of diabetic retinopathy (DR). However, the literature presents conflicting outcomes regarding this effect. For example, in a long-term study by Chow et al[29], with follow-up extending up to 10 years, 75% of eyes remained stable with inactive proliferative DR. Among non-blind eyes, 14% showed improvement and 10% progressed. Early vitreous hemorrhage occurred in approximately 6% of the eyes, all of which were associated with preexisting advanced retinopathy. Although cataract incidence increased significantly after transplantation (P < 0.01), impacting visual acuity, overall vision remained stable. Similar findings were reported in studies by Pearce et al[30] and Zech et al[31]. Reinforcing the trend toward long-term stabilization or improvement in DR post SPK.

In contrast, a short-term study (12-month follow-up) by Voglová et al[32] reported that early worsening of diabetic retinopathy occurred in about one-third of SPK recipients. Importantly, this worsening was generally mild, with no significant decline in visual acuity. Interestingly, Hb1ac reduction did not correlate with retinopathy progression, suggesting that changes were more reflective of the underlying disease dynamics rather than rapid glycemic improvement. Overall, retinopathy stabilized or improved in approximately 63% of patients, and over 25% showed improvement, highlighting the potential long-term ocular benefits of PT.

Effect on diabetic neuropathy

Diabetic autonomic neuropathy (DAN) is a common but often under-recognized complication of diabetes despite its well-documented association with increased morbidity and mortality in diabetic patients[33]. A Key subtype of DAN is cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy, which involves impaired autonomic regulation of cardiovascular reflexes. In A prospective study by Argente-Pla et al[34], 81 patients who underwent SPK were evaluated using cardiovascular autonomic reflex tests CART and followed for up to 10 years. These findings revealed that the Valsalva ratio was the earliest marker to improve, showing statistically significant enhancement by three years post-transplant (P < 0.001), with sustained improvement through year 5. Additionally, the systolic blood pressure response to standing - another key autonomic measure - showed significant improvement five years post-SPK (P = 0.03). Complementing these findings is a separate study by Navarro et al[35], provided early evidence that PTA, even in patients with normal renal function, can lead to improvement in diabetic autonomic neuropathy, particularly cardiovascular function, as a result of sustained normal glycemia following the restoration of endogenous insulin secretion.

Effect on diabetic nephropathy

Diabetic nephropathy (DN) is characterized by progressive kidney damage, including mesangial expansion, thickening of the glomerular basement membrane, and eventual glomerulosclerosis. A landmark study by Fioretto et al[36] demonstrated that long-term normoglycemia, achieved through PT, can reverse established structural kidney lesions. However, this process requires at least 10 years of tight metabolic control. These findings underscore the importance of achieving and maintaining early and sustained glycemic normalization, particularly before irreversible fibrosis develops. In addition to structural improvements, molecular markers such as long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs), are emerging as indicators of DN-related vascular injury. A recent study[37] showed that specific (lncRNAs) – MALAT1, LIPCAR, and LNC-EPHA6- are elevated in DN but normalize following SPK transplantation, unlike in KTA. These lncRNAs may serve as noninvasive biomarkers for tracking the severity of vascular injuries and the effectiveness of SPK. Overall, these findings suggest that SPK offers systemic benefits, not only improvement in glucose and kidney function but also reversing microvascular damage at a cellular and molecular level.

Integrated perspective

Across these domains —vascular, retinal, and renal —the overarching theme is that SPK, through the restoration of endogenous insulin and long-term metabolic normalization, offers widespread benefits in reversing or stabilizing diabetes-related complications. While short-term studies may show conflicting results due to early disease dynamics or limited follow-up, long-term data consistently favor SPK as a strategy not only for glycemic control but also for modifying the natural History of diabetic and organ damage. Further research with standardized outcome definitions and extended observation is essential to delineate the full spectrum of SPK’s systemic impact.

CARDIOVASCULAR OUTCOMES AFTER SPK

Patients with diabetes and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) are at high cardiovascular risk, even after KTA. In a propensity score matched study by Lange et al[38] compared to KTA, SPK was associated with significantly better cardiovascular outcomes, as SPK recipients had lower all-cause mortality and reduced cardiovascular mortality (3.3% vs 19%), as well as a lower incidence of major cardiovascular events (7% vs 28%). Echocardiography showed improved left ventricular function, and at 5 years post-transplant, SPK patients had better metabolic control, including lower HbA1c levels, improved blood pressure, and healthier lipid profiles — factors that are likely to have contributed to the cardiovascular benefits observed. In a registry-based cohort study of 486 T1DM patients with ESRD, Lindahl et al[39] found that those who underwent SPK transplantation had a 37% lower risk of cardiovascular death compared to those who received a living donor kidney transplant alone. Over a median follow-up of 7.9 years, SPK was associated with significantly improved cardiovascular survival, highlighting the long-term benefits of restoring normoglycemia in this high-risk population.

COMPLICATIONS OF SPK

Despite its substantial benefits, SPK is associated with a notable risk of surgical and medical complications, particularly in the early post-transplant operative period. Common surgical complications include pancreatic graft thrombosis, hemorrhage, anastomotic leaks, and graft pancreatitis, all of which can result in early graft loss and may require reoperation[40,41]. Infections, both in the surgical site and systemic, are frequent due to the intensity of immunosuppression, which also increases the long-term risk of opportunistic infections and malignancies. Delayed graft function, particularly of the pancreas, can complicate early management and monitoring. Rejection episodes, although less frequent with modern immunosuppressive regimens, remain a concern and can compromise both grafts. Furthermore, the need for lifelong immunosuppression introduces long-term risks, including nephrotoxicity, metabolic derangements, and cardiovascular effects. Contemporary SPK practices have led to significantly improved surgical outcomes, driven by better donor selection, shorter ischemia times, and enhanced surgical techniques and perioperative care. These advancements have resulted in fewer reoperations, lower graft pancreatectomy rates, and improved early pancreas graft survival[42].

LIVING DONOR PANCREAS

Approximately 200 living donor pancreas procedures have been performed worldwide[43], including both PTA and SPK transplants. Procurement was achieved via a distal hemi-pancreas pancreatectomy, with the laparoscopic technique having been used since 2000. Living donor pancreas transplantation is feasible and safe when donors are carefully selected through strict metabolic screening. Remarkably, there have been no reported donor deaths, and the adoption of laparoscopic distal pancreatectomy has helped reduce surgical morbidity. Recipient outcomes are favorable, with one-year pancreas graft survival exceeding 85%. The approach offers significant benefits, including immediate transplantation with improved HLA matching, reduced immunologic risk, and the potential for a lower immunosuppressive burden. Strategy is particularly beneficial for highly sensitized recipients, those with identical twins, or well-matched siblings, or patients aiming to preempt dialysis[44].

PANCREAS GRAFT FAILURE

The official UNOS/OPTN 2015 definition of pancreas graft failure includes several specific criteria designed to standardize reporting across transplant centers. Graft failure is recognized if any of the following events occur: Surgical removal of the pancreas graft, re-registration or listing for another pancreas or islet transplant, patient's death, or sustained insulin requirement of ≥ 0.5 U/kg/day for at least 90 consecutive days. Additionally, immediate graft non-function is defined as the removal of the graft within 14 days of transplantation[45]. However, this definition excludes essential glycemic measures such as C-peptide, HbA1c, and hypoglycemic frequency, failing to reflect actual metabolic function and outcomes. Therefore, Stratta et al[46] propose a graded or tiered definition of pancreas graft function by classifying graft outcomes into three functional categories. Optimal graft function is defined by complete insulin independence, near-normal HbA1c (≤ 6.5%), measurable C-peptide levels, and the absence of severe hypoglycemia. Partial or marginal graft function is characterized requirement of low-dose insulin or oral agents while still benefiting from improved glycemic control, lower HbA1c, and reduced hypoglycemic episodes with evidence of residual endogenous insulin production. Graft failure is characterized by the loss of endogenous insulin secretion, poor glycemic control, and a return to the pre-transplant insulin requirement. The latter classification addresses the limitation in the UNOS definition by offering a more comprehensive and functional assessment of the graft outcomes.

BEYOND PANCREAS TRANSPLANTATION: THE PROMISE OF ISLET AND STEM CELL THERAPIES

While this review primarily focuses on PT, it is important to acknowledge islet cell transplantation (ICT) as a less invasive yet promising alternative for achieving insulin Independence. Although its application has been more restricted by the severely limited number of donor pancreatic islets available, advances in immunosuppression and cell processing have led to improved outcomes[47]. The conventional process of ICT includes obtaining and isolating islets from a deceased donor pancreas, followed by infusing a sufficient mass of these islets into the portal vein. Utilizing the Edmonton group strategy of preferably T-cell depleting induction combined with maintenance tacrolimus and mycophenolate mofetil, patients have achieved and maintained Insulin independence rates exceeding 50% at five years, surpassing earlier results from the original Edmonton protocol using less potent immunosuppressive regimen[48,49]. Recent scientific advances in the realm of ICT, borne from autologous induced pluripotent stem cell (iPSC) derived beta cells, have found long-term success for a select patient with T1DM as part of a clinical study in achieving sustained insulin independence of over a year can help overcome the limited supply of islet cells derived from deceased donor pancreas[50]. This achievement came after extensive preclinical testing, including the transplantation of these islets into immunodeficient mice and nonhuman primates[51,52]. The cells were generated by chemically reprogramming mesenchymal stromal cells obtained from the patient’s own adipose tissue into iPCSs[53]. These iPSCs were differentiated into islet-like clusters comprising approximately 60% beta cells in the aggregate, and after rigorous safety evaluations, a total dose of 1488283 islet equivalents was injected beneath the anterior abdominal rectus sheath[50]. While a more thorough discussion on the implantation of autologous iPSC-derived islets is beyond the scope of this review, it represents a compelling direction in the evolving treatment landscape for diabetes. Despite the promising proof of concept, the high complexity cost and prolonged safety testing required for generating patient-specific iPSC- derived islets currently limit their widespread applicability. Nonetheless, ongoing clinical trials will be instrumental in determining the feasibility of this innovative therapy as a radical alternative to conventional PT[54].

CONCLUSION

SPK transplantation remains a vital option for patients with diabetes and ESRD, offering not only the potential for sustained insulin independence but also improved patient and graft survival with markedly better quality of life, along with significant mitigation of diabetic complications. SPK affords a reduction in cardiovascular morbidity and mortality compared to KTA due to advancements in surgical techniques, donor selection, and perioperative management. Current challenges in the field of PT still include early surgical and long-term immunologic risks, further compounded by declining transplant volumes, limited organ availability, and the advancement of medical therapies for diabetes. ICT represents a promising but still investigational alternative to PT, with ongoing research needed to clarify the long-term efficacy and clinical applicability.

Provenance and peer review: Invited article; Externally peer reviewed.

Peer-review model: Single blind

Specialty type: Transplantation

Country of origin: United States

Peer-review report’s classification

Scientific Quality: Grade B, Grade B, Grade B

Novelty: Grade B, Grade B, Grade C

Creativity or Innovation: Grade B, Grade B, Grade C

Scientific Significance: Grade B, Grade B, Grade C

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/

P-Reviewer: Cao Y, MD, China; Xie Y, PhD, Postdoctoral Fellow, United States S-Editor: Liu JH L-Editor: A P-Editor: Zhang YL