Published online Mar 18, 2026. doi: 10.5500/wjt.v16.i1.110910

Revised: August 12, 2025

Accepted: November 11, 2025

Published online: March 18, 2026

Processing time: 210 Days and 13.1 Hours

While varices and variceal bleeds are well-known and feared complications of advanced cirrhosis and portal hypertension, omental variceal bleed are a rare sequala even in patients with known esophageal or gastric varices. While rare, omental varices pose a risk for hemoperitoneum if ruptured, which is a life-threatening complication with high mortality rates despite surgical intervention.

This report reviews the case of a patient 36-year-old female with alcohol related cirrhosis decompensated by ascites, but no history of varices admitted for hemo

This case report and literature review stresses the importance of early conside

Core Tip: While varices and variceal bleeds are well-known and feared complications of advanced cirrhosis and portal hypertension, omental varices are a rare sequala even in patients with known esophageal or gastric varices. Omental varices pose a risk for hemoperitoneum if ruptured, which is a life-threatening complication with high mortality rates despite surgical intervention. This case report reviews the first documented case of successful liver transplantation after hemorrhagic shock secondary to omental variceal bleed.

- Citation: Currier EE, Won CY, Parraga X, Lee KS, Saberi B. Hemoperitoneum from omental variceal bleed resulting in first documented successful liver transplant: A case report. World J Transplant 2026; 16(1): 110910

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3230/full/v16/i1/110910.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5500/wjt.v16.i1.110910

While varices and variceal bleeds are well-known and feared complications of advanced cirrhosis and portal hyper

A 36-year-old female with a past medical history of alcohol-related cirrhosis decompensated by ascites was transferred to the emergency department of a large, urban hospital due to a one-week history of progressive weakness and abdominal pain.

The patient had initially presented to an outside hospital due to severe abdominal pain where she was noted to have a hemoglobin of 5.8 g/dL, and computed tomography (CT) angiography of the abdomen was notable for hemoperitoneum but negative for active bleeding. She was transfused with 3 units of packed red blood cells and transferred to the nearest tertiary care center.

Personal history notable for alcohol-related cirrhosis decompensated by ascites. Of note, given six months of sobriety, her cirrhosis had recently been stable, and her diuretics had been weaned. Less than two months prior to presentation, she had a screening esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), which was negative for evidence of gastric or esophageal varices.

Personal history notable for alcohol and substance use disorder.

On arrival to the Emergency Department, patient was endorsing dizziness, and vitals were notable for tachycardia (heart rate: 110), hypotension (96/60); without any fever. Her physical exam was notable for jaundice and mild abdominal distention.

MELD 3.0 on arrival was 30 (Cr 1.7 mg/dL, Na 132 mmol/L, total bilirubin 3.3 mg/dL, albumin 2.5 g/dL, international normalized ratio 2.3). Hemoglobin on arrival was 7.9 g/dL; however, the patient subsequently became more hypotensive with a mean arterial pressure in the 50s, requiring pressor support. Hemoglobin was repeated at this time and was noted to be 6.6 g/dL.

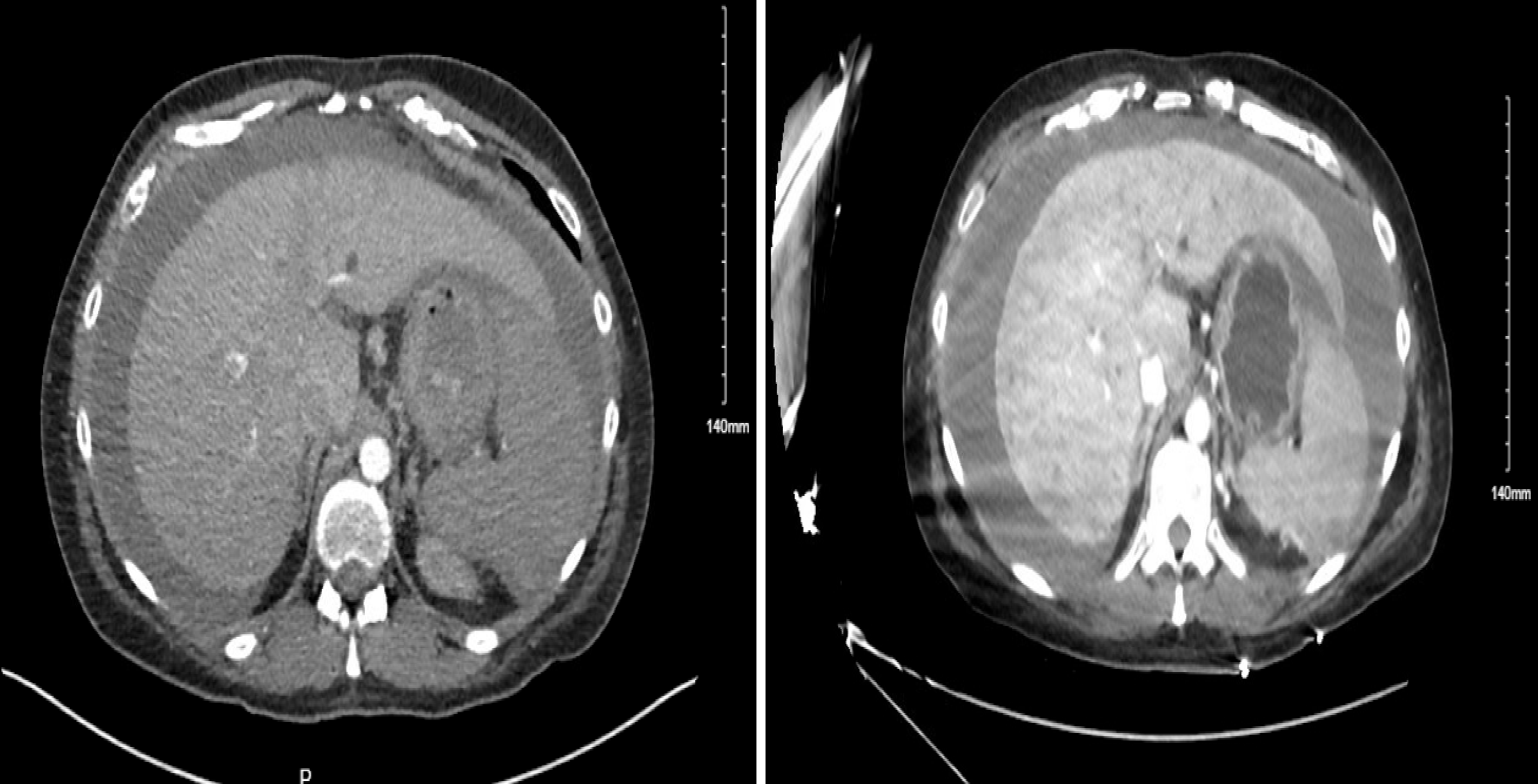

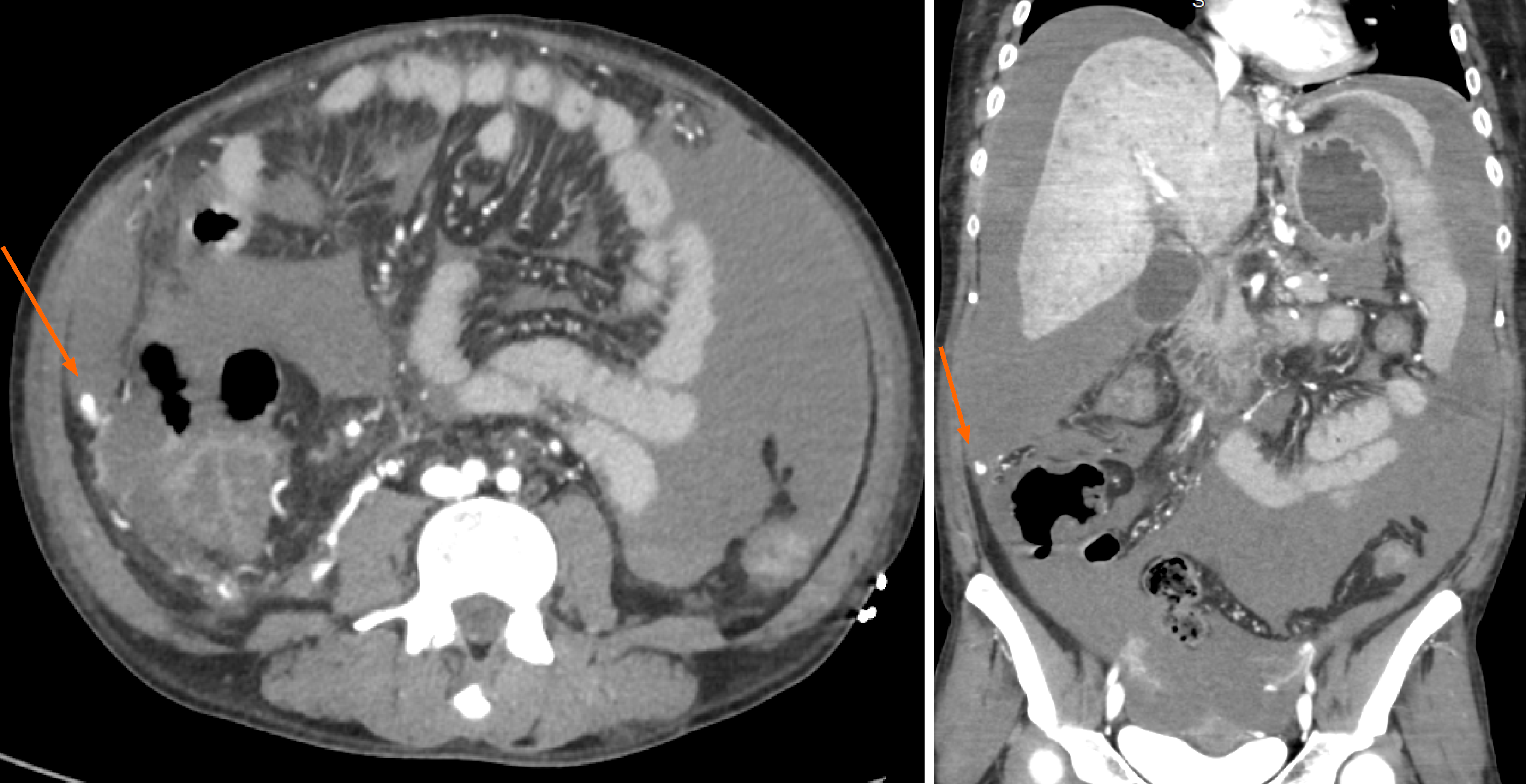

CT angiogram was repeated which was notable for stable large-volume ascites with hemoperitoneum with no evidence of active bleed (Figures 1 and 2).

She was transferred to the medical intensive care unit (ICU), where she was noted to have rapidly escalating pressor requirements despite adequate transfusion and abrupt abdominal distention. Given progressive rapid hemodynamic instability, the patient underwent emergency laparotomy, which revealed brisk omental variceal bleeding in the right upper quadrant and adhesions from omentum to the pelvis with additional bleeding noted. Hemostasis was achieved with cautery and hemoclips and over 2 liters of blood was evacuated; no pathologic samples or intra-operative photo

Hemorrhagic shock secondary to hemoperitoneum from ruptured omental varices.

Emergency laparotomy with hemostasis via cautery and hemoclips.

After conclusion of the surgery, the patient was transferred back to the medical ICU, where her condition stabilized, pressors were weaned, MELD down-trended to 22, and she underwent liver transplant evaluation. Her course was complicated by hyperkalemia and acute kidney failure secondary to hypovolemia requiring brief continuous renal replacement therapy; however, renal function and hemodyamic instability improved and she was transferred out of the ICU.

Approximately two weeks after the presentation for hemorrhagic shock and hemoperitoneum secondary to ruptured omental varices, she underwent an uncomplicated orthotopic liver transplant. Over six months after transplant, the patient has remained stable with no further bleed, repeat hospitalization, or evidence of transplant rejection.

The PubMed (2000-2025) database was queried for case reports regarding intra-abdominal and omental variceal bleed, and abstracts published in English were screened. Case reports regarding spontaneous intra-abdominal varices in patients without cirrhosis or bleeding in pregnancy were not included. Demographic data and outcomes from fourteen patients can be found in Tables 1 and 2, respectively[1-10].

| Average age | 48.7 years (range: 36-63) |

| Sex | |

| Male | 10 (71.4) |

| Female | 4 (28.6) |

| Cirrhosis previously diagnosed | 100 (14/14) |

| Alcohol related cirrhosis? | 92.9.7 (13/14) |

| Prior history of varices | |

| Yes | 28.6 (4/14) |

| Unknown | 57.1 (8/14) |

| No | 14.3 (2/14) |

| Diagnostic method | |

| CTA | 64.3 (9/14) |

| Surgery | 14.3 (2/14) |

| Paracentesis | 14.3 (2/14) |

| Autopsy | 7.1 (1/14) |

| Intervention | |

| Surgery | 71.4 (10/14) |

| TIPS | 14.3 (2/14) |

| IR- glue embolization | 7.1 (1/14) |

| N/A | 7.1 (1/14) |

| Death | |

| Yes | 57.1 (8/14) |

| No | 42.9 (6/14) |

| Source of bleed | |

| Omental | 50.0 (7/14) |

| Peritoneal | 7.1 (1/14) |

| Mesenteric | 7.1 (1/14) |

| Retroperitoneal | 7.1 (1/14) |

| Multiple sources | 7.1 (1/14) |

| Gallbladder | 14.3 (2/14) |

| Unknown | 7.1 (1/14) |

The American Association for the Study of Liver Disease and American Gastrological Association have noted that gastroesophageal varices (GEV) are present in 30%-40% of those with compensated cirrhosis and up to 85% of patients with decompensated cirrhosis, with the most common variceal site being esophageal (up to 85%) followed by gastric (15%-25%)[11,12]. GEV bleed occurs at rate of 10%-15% per year and the 5-year mortality after hemorrhage ranges from 20%-80%[11].

While omental variceal bleeds have been documented since 1978, they remain extremely rare sequelae of portal hypertension and have been noted in prior case reports to be more common in middle-aged men with advanced cirrhosis[13]. Intra-abdominal variceal bleeds are associated with hepato-renal syndrome, encephalopathy, and increased mortality rate[11]. Due to its rarity, there is very limited data on the prevalence of omental varices; however, one study in 1995 reported that less than 20% of individuals with portal hypertension had radiologic evidence of omental varices[14]. No further studies have commented on the incidence of omental varices and it is unknown if they are associated with complications of cirrhosis, such as portal vein or SMV thrombosis, or differences in anatomy.

Furthermore, there is limited information regarding the mortality rate of omental variceal bleed. Upon review of the case reports available on PubMed, there was a 57% mortality rate within 2-week of presentation despite procedural/surgical intervention. This is a stark contrast to the mortality rate of those with GEV bleed. A review of these case reports notes a consistent presentation of progressive abdominal pain followed by hypotension and rapidly increasing abdominal girth. Additionally, review of these cases notes that surgical intervention was often preferred over pursuit of transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) or interventional radiology embolization of bleed, which was mirrored in this patient’s presentation. While the decision to pursue surgery over TIPS in many of the cases in unknown, it is likely due to the elevated risk of TIPS in high MELD patients. In this patient’s presentation, due to her rapid clinical deterioration and abdominal distention is conjunction with her high MELD, surgical intervention was preferred over high risk TIPS.

Despite a rapid diagnosis of hemorrhagic shock and hemoperitoneum with paracentesis or CT, adequate volume resuscitation, and intervention, either with surgical hemostasis or TIPS, many patients continued to have a rapid decline and died within days of presentation. While their deaths appear to have ultimately been multifactorial in the setting of possible concomitant septic shock, multi-organ failure, etc., this highlights the dangers of omental and intra-abdominal variceal bleeding and the guarded prognosis this rare manifestation of portal hypertension holds, particularly in comparison to GEV bleed.

Of note, this case report highlights a patient who is unique in multiple facets. This patient was a young female, which is contrary to most case reports in which the average age is 49 years old and patients are typically male (11 out of 14 patients). Next, while having decompensated cirrhosis, she had a recent screening EGD with no evidence of GEV, making the patient’s odds of having any other varices, let alone a variceal hemorrhage, significantly low. On review of prior case reports, it was reported that 28.6% had a history of esophageal varices, however many case reports did not comment on prior variceal history, so this number may be falsely low. Furthermore, given this patient’s hemodynamic stabilization after surgical intervention, she was able to undergo transplant evaluation and ultimately underwent uncomplicated orthotopic liver transplant during the same admission.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first case report of a successful transplant after intra-abdominal variceal bleed. Interestingly, outside of expediting her transplant evaluation and surgery, there were no known perioperative complications of the recent omental bleed on her transplant. It is likely that her recent six-month history of sobriety prior to presentation and young age, in conjunction with rapid diagnosis and intervention at a liver transplant center, led to her exceedingly successful, albeit rare, outcome.

This case stresses the importance of early consideration of hemoperitoneum and intraabdominal varices in cirrhotic patients with refractory shock, even in those with no prior history of varices. Additionally, this shows the need for rapid multidisciplinary treatment with interventional radiology, surgery, and transplant hepatology to maximize patient outcomes. While the prognosis in intra-abdominal variceal hemorrhage in patients with cirrhosis remains a guarded prognosis, this case of successful liver transplant after omental variceal bleed highlights the possibility of success with rapid diagnosis and treatment of the condition.

| 1. | Masood I, Bradley M, Cavazos-Escobar E, Patel SB, Wong BS. Traumatic omental variceal rupture-treatment with transjugular portosystemic shunt (TIPS) and embolization. Radiol Case Rep. 2023;18:2978-2981. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Sarantitis I, Satherley H, Varia H, Pettit S. Recurrent major umbilical bleeding caused by omental varices in two patients with umbilical hernia and portal hypertension. BMJ Case Rep. 2015;2015:bcr2015209647. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wongjarupong N, Said HS, Huynh RK, Golzarian J, Lim N. Hemoperitoneum From Bleeding Intra-Abdominal Varices: A Rare, Life-Threatening Cause of Abdominal Pain in a Patient With Cirrhosis. Cureus. 2021;13:e18955. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Bataille L, Baillieux J, Remy P, Gustin RM, Denié C. Spontaneous rupture of omental varices: an uncommon cause of hypovolemic shock in cirrhosis. Acta Gastroenterol Belg. 2004;67:351-354. [PubMed] |

| 5. | Finley DS, Lugo B, Ridgway J, Teng W, Imagawa DK. Fatal variceal rupture after sildenafil use: report of a case. Curr Surg. 2005;62:55-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Aslam N, Waters B, Riely CA. Intraperitoneal rupture of ectopic varices: two case reports and a review of literature. Am J Med Sci. 2008;335:160-162. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Mahmoudi M, Gharbi G, Khsiba A, Jallouli A, Mohamed AB, Yakoubi M, Medhioub M, Hamzaoui L, Bouzaidi K, Azouz MM. A rare cause of spontaneous hemoperitoneum: intra-abdominal vein rupture. Future Sci OA. 2023;9:FSO891. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Sincos IR, Mulatti G, Mulatti S, Sincos IC, Belczak SQ, Zamboni V. Hemoperitoneum in a cirrhotic patient due to rupture of retroperitoneal varix. HPB Surg. 2009;2009:240780. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Pravisani R, Bugiantella W, Lorenzin D, Bresadola V, Leo CA. Fatal hemoperitoneum due to bleeding from gallbladder varices in an end-stage cirrhotic patient A case report and review of the literature. Ann Ital Chir. 2016;87:S2239253X16025147. [PubMed] |

| 10. | Chu EC, Chick W, Hillebrand DJ, Hu KQ. Fatal spontaneous gallbladder variceal bleeding in a patient with alcoholic cirrhosis. Dig Dis Sci. 2002;47:2682-2685. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Garcia-Tsao G, Abraldes JG, Berzigotti A, Bosch J. Portal hypertensive bleeding in cirrhosis: Risk stratification, diagnosis, and management: 2016 practice guidance by the American Association for the study of liver diseases. Hepatology. 2017;65:310-335. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1108] [Cited by in RCA: 1499] [Article Influence: 166.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (3)] |

| 12. | Henry Z, Patel K, Patton H, Saad W. AGA Clinical Practice Update on Management of Bleeding Gastric Varices: Expert Review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;19:1098-1107.e1. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 23.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Shapero TF, Bourne RH, Goodall RG. Intraabdominal bleeding from variceal vessels in cirrhosis. Gastroenterology. 1978;74:128-129. [PubMed] |

| 14. | Cho KC, Patel YD, Wachsberg RH, Seeff J. Varices in portal hypertension: evaluation with CT. Radiographics. 1995;15:609-622. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 89] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/