Published online Mar 18, 2026. doi: 10.5500/wjt.v16.i1.110683

Revised: August 8, 2025

Accepted: October 24, 2025

Published online: March 18, 2026

Processing time: 184 Days and 15.9 Hours

With the increasing use of laparoscopic techniques in living-donor kidney tran

To address the issue of short right renal veins, several surgical strategies have been proposed. In this report, we describe our experience with three cases in which venous extension was successfully achieved using a venous cuff inter

Venous cuff interposition represents an effective technique for managing short renal veins in living-donor kidney transplantation. It provides additional length and flexibility, easing anastomotic tension and supporting successful transp

Core Tip: In living-donor kidney transplantation, short renal veins following laparoscopic donor nephrectomy can complicate vascular anastomosis. The use of a venous cuff interposition is a practical solution that increases vein length and flexibility, reduces anastomotic tension, and facilitates a secure end-to-side anastomosis to the recipient’s external iliac vein, thereby optimizing hemodynamic stability and potentially decreasing the incidence of vascular complications.

- Citation: Lekehal B, Ait Youssef N, Lekehal M, Bakkali T, Jdar A, Bounssir A. Vein cuff interposition for short renal vein in living-donor kidney transplantation: Three case reports and review of literature. World J Transplant 2026; 16(1): 110683

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3230/full/v16/i1/110683.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5500/wjt.v16.i1.110683

Living-donor kidney transplantation, including both related and unrelated donors, is currently an established clinical strategy to address the persistent shortage of suitable donor organs[1]. With the growing use of minimally invasive techniques, laparoscopy is increasingly used in living-donor kidney transplantation. In the hand-assisted laparoscopic living-donor kidney procedure, a short renal vein poses technical challenges during graft placement into the iliac fossa, potentially increasing the risk of postoperative complications[2-5]. Multiple techniques have been used to overcome the technical difficulties associated with exceptionally short renal veins. We present our experience using a vein cuff inter

Case 1: A 45-year-old female with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) secondary to autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease (ADPKD) presented for elective living-donor renal transplantation.

Case 2: A 38-year-old male with end-stage renal failure presented for a living-donor kidney transplant.

Case 3: A 30-year-old female with ESRD secondary to diabetic nephropathy presented for elective living-donor kidney transplantation.

Case 1: The patient was diagnosed with ADPKD in her 30s. It progressively led to chronic kidney disease and eventually ESRD. She had been on maintenance hemodialysis for 2 years prior to transplantation. A living-related donor kidney transplant was planned. The donor was a biological relative, and the right kidney was procured via hand-assisted laparoscopic nephrectomy. Preoperative donor imaging revealed a short renal vein and two renal arteries.

Case 2: The patient had experienced progressive renal dysfunction over the prior several years, eventually requiring renal replacement therapy. He was evaluated and deemed an appropriate candidate for living-donor renal transplantation. The donor was a living biological relative who underwent right-sided donor nephrectomy.

Case 3: The patient had a long-standing history of type 1 diabetes mellitus complicated by progressive diabetic nep

Case 1: The patient had a known history of ADPKD leading to ESRD. No prior history of transplant surgery nor sig

Case 2: The patient had a known history of chronic kidney disease leading to end-stage renal failure. He had been on maintenance hemodialysis for > 1 year prior to transplantation. There was no history of prior abdominal surgeries, vascular disorders, nor coagulopathies.

Case 3: The patient had a known history of insulin-dependent type 1 diabetes mellitus, diagnosed in adolescence. She developed diabetic nephropathy in her 20s, leading to progressive renal decline. No other significant comorbidities nor prior surgical history were reported.

Case 1: The patient’s family history was notable for ADPKD affecting multiple first-degree relatives, including her kidney donor. There were no known hereditary coagulopathies nor vascular disorders.

Case 2: Family history was significant for kidney disease in a first-degree relative, who served as the donor. No known hereditary renal or systemic diseases beyond chronic kidney disease were reported. The patient denied any personal history of hypertension, diabetes, or cardiovascular disease prior to renal failure.

Case 3: The patient had no known familial history of hereditary renal diseases nor autoimmune conditions. The donor was a healthy biological relative with no history of chronic illness.

Case 1: Preoperative physical examination was unremarkable. Vitals were stable, and the patient exhibited no signs of active infection nor systemic illness. Abdominal examination revealed bilateral flank fullness, consistent with polycystic kidneys.

Case 2: Preoperative physical examination revealed a hemodynamically stable patient with signs consistent with chronic renal disease. There was no evidence of edema, ascites, nor infection. Cardiopulmonary and abdominal examination findings were within normal limits.

Case 3: Upon preoperative examination the patient was alert, oriented, and hemodynamically stable. No signs of fluid overload or infection were present. Abdominal examination was unremarkable, and there were no signs of vascular compromise.

Case 1: The patient’s preoperative tests showed elevated serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen, consistent with ESRD. The electrolyte panel was within dialysis-adjusted limits. The coagulation profile was within normal limits. The panel-reactive antibody test was negative. ABO compatibility was confirmed between the donor and recipient.

Case 2: The patient’s hemoglobin showed mild anemia consistent with ESRD. Serum creatinine was elevated. Electrolytes were within acceptable limits following dialysis. Glycated hemoglobin was moderately elevated, consistent with suboptimally controlled diabetes. The coagulation profile was within the normal range. The crossmatch test was negative, and the human leukocyte antigen typing showed compatibility test was acceptable, and the panel-reactive antibody test was low.

Case 3: The patient’s hemoglobin showed mild anemia consistent with ESRD. Serum creatinine was elevated. Electrolytes were within acceptable limits following dialysis. Glycated hemoglobin was moderately elevated, consistent with sub

Case 1: Preoperative recipient imaging showed no significant atherosclerotic disease in iliac vessels and normal venous anatomy. Donor computed tomography angiography showed the right kidney with a very short intrahilar renal vein and two renal arteries.

Case 2: Preoperative recipient imaging showed no significant atherosclerosis nor calcification of the iliac vessels, indicating suitability for transplantation. Donor imaging revealed a right kidney with a short renal vein.

Case 3: Preoperative recipient imaging showed normal anatomy of the iliac vessels and no significant vascular cal

A transplant surgery team, nephrologist, and anesthesiologist were involved in preoperative planning.

A multidisciplinary transplant team including nephrologists, transplant surgeons, and anesthesiologists had evaluated and optimized the patient preoperatively. Intraoperatively, the transplant surgical team addressed unexpected vascular challenges through collaborative technical adaptation.

The case was reviewed by the multidisciplinary transplant team including transplant surgeons, nephrologists, anesthesiologists, and radiologists. Intraoperative challenges were addressed by the surgical team using preestablished recon

ESRD due to ADPKD, status post-renal transplantation with intraoperative venous anastomotic complication secondary to short donor renal vein.

ESRD secondary to chronic kidney disease; intraoperative vascular challenge due to extremely short donor renal vein requiring complex venous reconstruction.

ESRD due to diabetic nephropathy with intraoperative venous reconstruction for short intrahilar renal vein during living-donor renal transplantation.

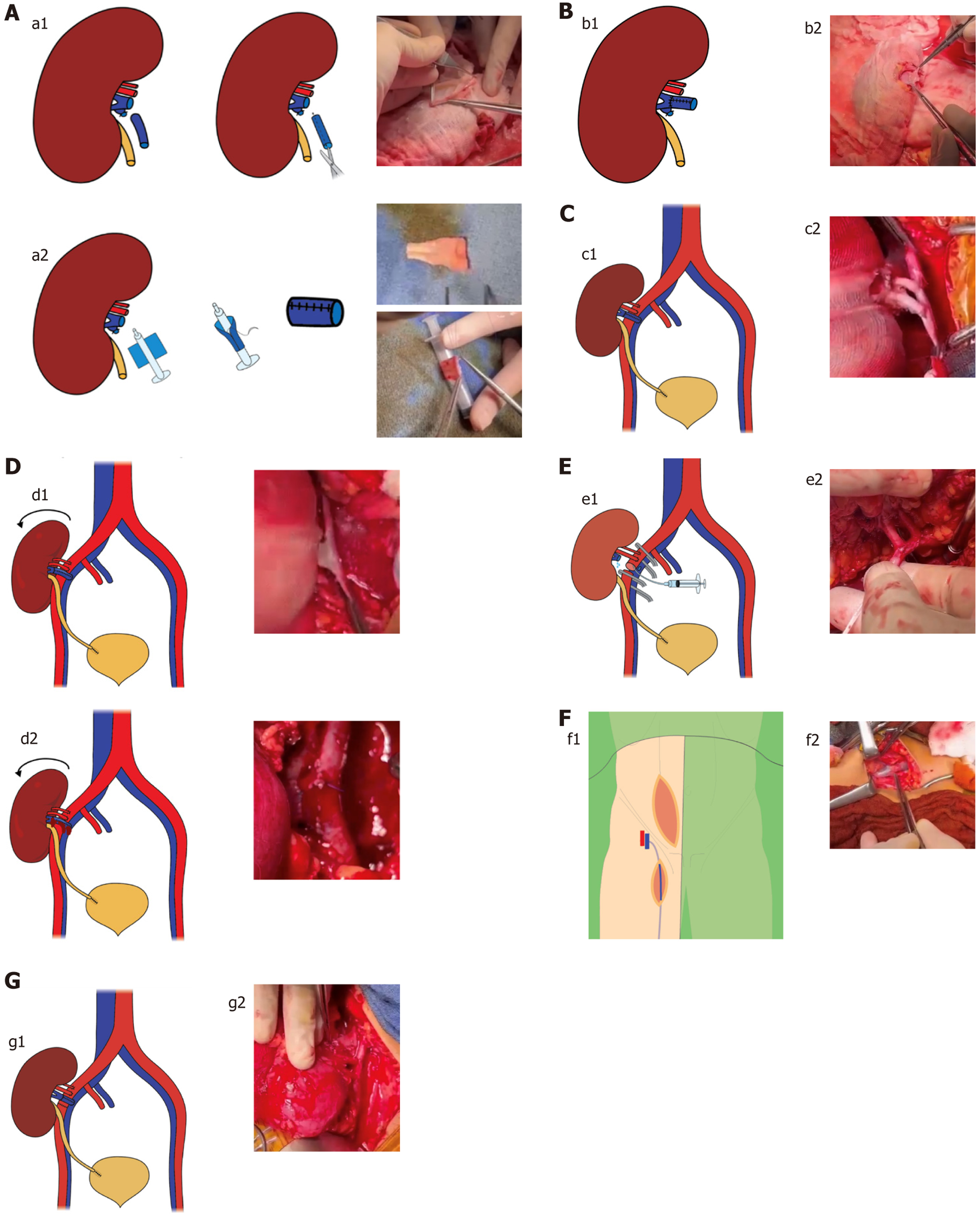

During the bench preparation, a venous cuff was constructed using the donor’s gonadal vein and anastomosed end-to-end to the donor renal vein to achieve sufficient venous length (Figure 1A and B). Transplantation was initially performed in the recipient’s right iliac fossa via the pararectal approach. An end-to-side venous anastomosis was created with the fully mobilized right external iliac vein. Subsequently, the two renal arteries were anastomosed end-to-side to the external iliac artery (Figure 1C). Following declamping and graft repositioning, significant tension was observed on the venous anastomosis, resulting in bleeding at the cuff site (Figure 1D). To address this, the iliac vessels were reclamped. The iliac artery was transected to allow for graft perfusion and flushing (Figure 1E). Given the insufficient length and fragility of the initial gonadal vein cuff, a new cuff was fashioned using the recipient’s great saphenous veins, which provided superior length and tensile strength (Figure 1F). This newly fashioned cuff was then anastomosed end-to-end to the donor’s renal vein. After perfusing and rinsing the graft, a new end-to-side anastomosis was performed to the recipient’s external iliac vein. The final end-to-end anastomosis of external iliac artery was completed before declamping (Figure 1G).

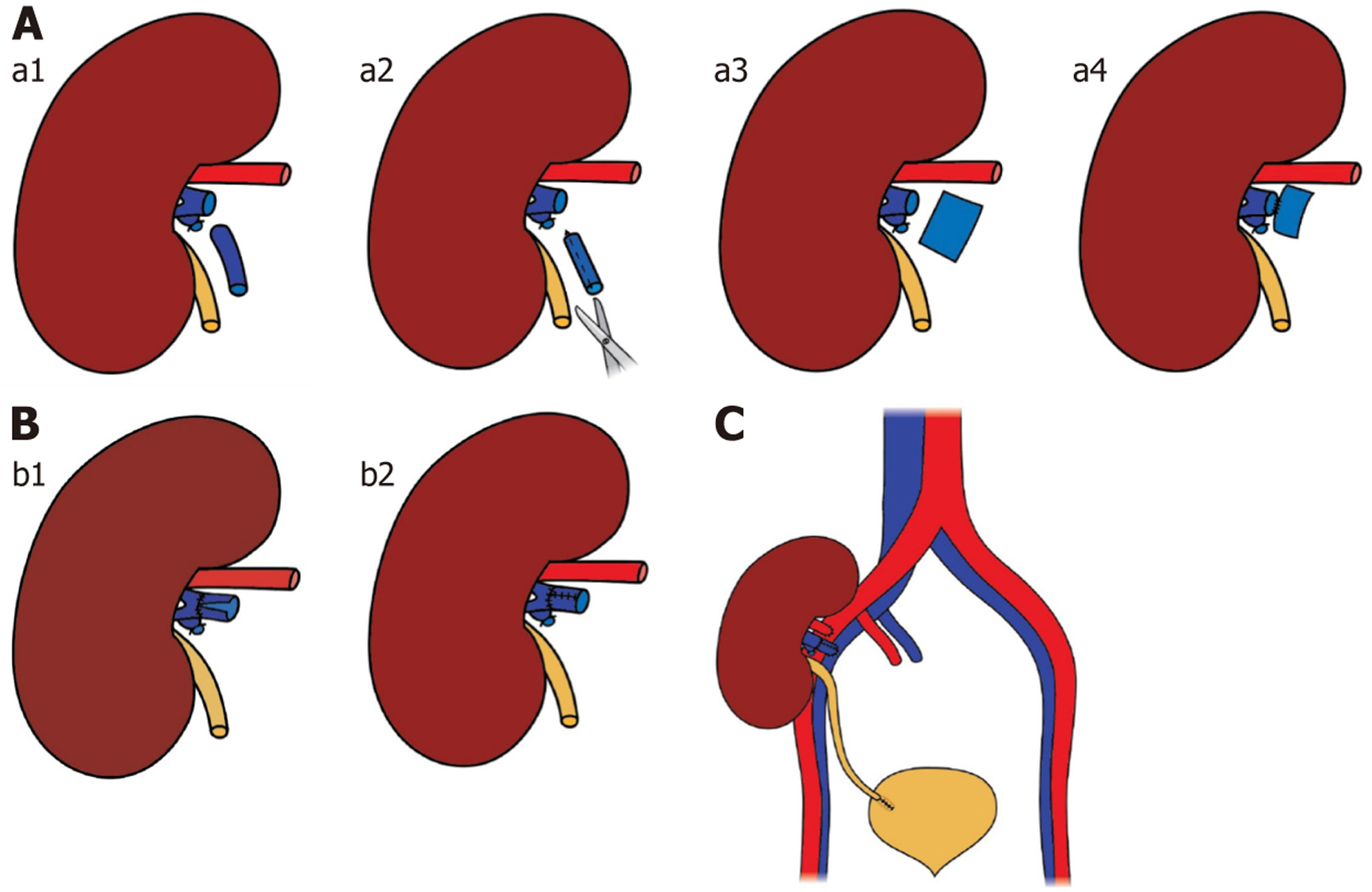

The right donor kidney was retrieved using hand-assisted laparoscopic nephrectomy. However, technical challenges during the procedure resulted in a renal vein stump measuring approximately 1.0 cm in length, making a direct venous anastomosis unfeasible. To address this, a vein extension using the donor’s gonadal vein was performed, allowing the transplant to proceed without further complications. The remaining renal vein was located near the renal hilum and had a significantly larger diameter than the gonadal vein, preventing a direct end-to-end anastomosis. Consequently, the gonadal vein required surgical remodeling to match the caliber and configuration of the renal vein.

A segment of the gonadal vein, ~3 mm in diameter and three times the circumference of the renal vein, was harvested and opened longitudinally to create a patch graft. A suture was first placed between the center of the posterior wall of the renal vein and the midpoint of the graft, with the graft positioned intimal side up. Posterior wall suturing proceeded distally within the lumen until the apex of the renal vein was reached and passed (Figure 2A).

The same technique was applied proximally, bringing the two ends of the graft together near the mid-anterior wall of the gonadal vein. Excess graft tissue was excised, and the anastomosis was completed by approximating and closing the free ends of the vein graft (Figure 2B). The remodeled gonadal vein was anastomosed end-to-end with the renal vein. An end-to-side anastomosis was performed with a fully mobilized right external iliac vein. The renal artery was anastomosed to the recipient’s right external iliac artery using 6-0 prolene sutures (Figure 2C).

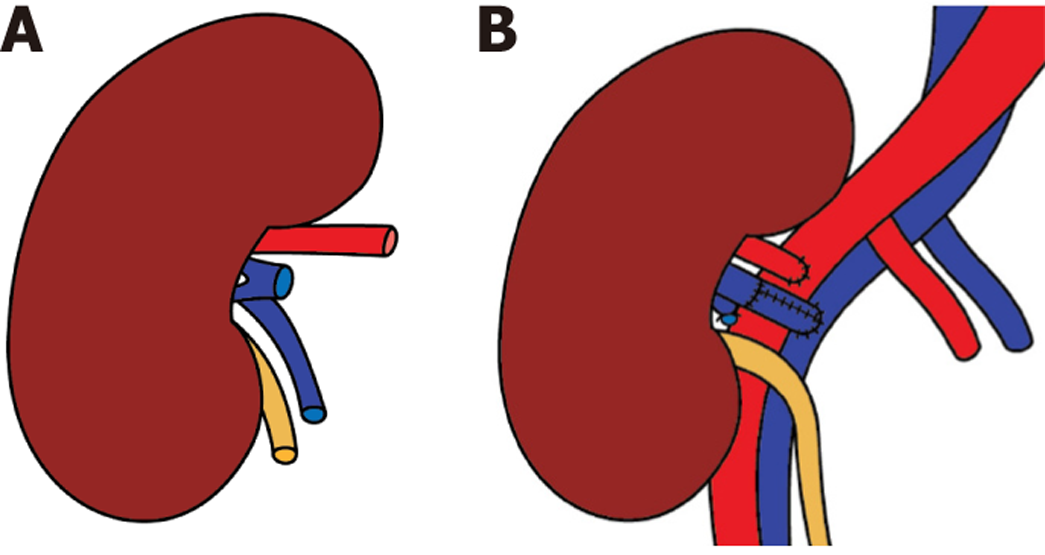

The right donor kidney was retrieved via hand-assisted laparoscopic nephrectomy. Intraoperatively, the donor renal vein was found in the intrahilar region and measured < 1.0 cm in length, posing a significant challenge for venous anastomosis (Figure 3A). An attempt to transpose the recipient’s iliac vein was unsuccessful due to its firm fixation to the pelvic floor.

During back-table preparation, a venous cuff extension was constructed using the donor’s gonadal vein, as previously described in Case 1. This cuff was anastomosed to the renal vein, enabling tension-free implantation of the graft in the right iliac fossa. The extended renal vein and renal artery were anastomosed to the recipient’s right external iliac vein and artery, respectively, using 6-0 prolene sutures (Figure 3B). Upon declamping, immediate reperfusion of the graft was observed with excellent vascular flow.

The revised anastomoses were hemostatic, and reperfusion of the graft was successful with good urine output. Postoperative Doppler ultrasonography confirmed patent arterial and venous flows. The standard immunosuppressive regimen was initiated, and the patient was monitored in the transplant intensive care unit. Renal function showed a downward trend in serum creatinine postoperatively. Imaging follow-ups at 6, 12, and 18 months showed no signs of vascular compromise nor thrombosis. The patient experienced no complications and maintained stable renal function throughout the follow-up period.

Upon vascular clamp release the kidney allograft reperfused immediately. No intraoperative or immediate postoperative complications were observed. The patient was transferred to the transplant intensive care unit in stable condition. Postoperative Doppler ultrasound confirmed good graft perfusion with patent arterial and venous anastomoses. Renal function showed progressive improvement over the early postoperative period, with decreasing serum creatinine and adequate urine output. The patient experienced no complications and maintained stable renal function over a 2-year follow-up period.

The patient demonstrated immediate graft function postoperatively. Doppler ultrasound confirmed patency of all vascular anastomoses. No intraoperative nor early postoperative complications occurred. At 6, 12, and 18 months of follow-up, the patient remained clinically stable with excellent renal allograft function, experiencing no complications and maintaining consistent renal function throughout.

Laparoscopic living-donor nephrectomy has been widely adopted as a minimally invasive surgical approach, offering reduced morbidity compared with conventional open-donor nephrectomy[6]. Hand-assisted laparoscopic living-donor nephrectomy offers potential benefits such as reduced donor morbidity, shorter hospital stay, and faster recovery. Furthermore, it has demonstrated comparable short-term and long-term allograft functional outcomes to those of open-donor nephrectomy[7-9]. Although the left kidney is typically preferred for hand-assisted laparoscopic living-donor nephrectomy due to its longer renal vessels, short renal vein length may still present technical challenges for graft im

Anatomically, the right renal vein is ~5.0 cm shorter than the left renal vein[12]. Renal grafts with vein lengths < 2.5 cm are particularly susceptible to technical complications, especially in recipients with obesity (with deep iliac vessels) or when the donor kidney is large. These challenges have contributed to the preferential use of the left kidneys and their predominance in living-donor transplantation[13].

All our allografts were obtained via laparoscopic donor nephrectomy and originated from right kidney donors, each characterized by a short renal vein. In case 2, the limited venous length resulted from intraoperative technical difficulties encountered during graft retrieval, while in cases 1 and 3, the renal veins were anatomically short (< 1.0 cm) with intrahilar terminations. The presence of a short renal vein during graft implantation presented several intraoperative challenges. It limits surgical visibility and maneuverability, creates tension on the venous anastomosis, and increases the risk of vascular complications such as bleeding, thrombosis, and kinking. The associated prolongation of warm ischemia time may adversely affect early graft function[2,5,14]. The difficulty in positioning the graft within the iliac fossa also contributes to a higher incidence of postoperative complications[15,16].

In case 1 of our series, considerable tension was noted at the venous anastomosis following graft repositioning, resulting in bleeding at the site of the venous cuff. This was attributed to the inadequacy of the gonadal vein cuff, which was both short and structurally fragile, rendering it insufficient to provide the necessary extension of the donor renal vein. However, transection of the external iliac artery allowed for continuous perfusion and flushing of the renal graft throughout the repair, thereby minimizing warm ischemia time.

Two main strategies were used to obtain a renal vein of suitable length from a living donor. The first involved maximizing the venous length during organ retrieval. This can be achieved through open surgery with a caval cuff[17] or in laparoscopic procedures by using hand-assisted techniques such as the endovascular gastrointestinal anastomosis modified stapler approach[15,18], Hem-o-lok application[19], or hand-assisted cavotomy[20]. Excessive extension of the harvested renal vein may significantly increase injury to the donor’s vena cava[3]. Nevertheless, despite these measures, in certain cases the renal vein remains insufficiently long. The second approach focuses on minimizing the distance between the graft and the recipient’s vasculature during implantation to accommodate a shorter vein. Various techniques have been described to address this challenge. One method involves the transposition or extensive mobilization of the recipient’s common and external iliac veins, which is a straightforward maneuver that facilitates secure venous anast

This method has limited applicability in patients with a deep pelvis or who are obese and may increase the risk of lymphatic complications resulting from injury to the lymphatics because of the extensive dissection required[4]. In all cases, an attempt was made to transpose the external iliac vein; however, this maneuver proved insufficient to com

In our experience managing renal transplants with short venous length, we favored the use of the donor’s gonadal vein due to its rapid and straightforward retrieval during laparoscopic nephrectomy. Additionally, the recipient’s saphenous vein serves as a readily accessible alternative, particularly in intraoperative complications (as in case 1), providing a reliable and high-quality venous conduit of adequate length.

While several renal vein extension techniques have been proposed to address short renal veins, their success remains variable, and long-term outcomes are not well established. A significant concern is the mismatch in diameter between the renal vein and the interposed vascular graft, which may predispose the patient to thrombosis. Additionally identifying a vein that is adequately matched in size and quality for effective renal vein extension can be challenging[15,27]. However, the use of autologous grafts such as the saphenous and superficial femoral veins requires a separate harvesting pro

Allogenic vascular grafts combine favorable characteristics, including high long-term patency, resistance to degradation, extended preservation capability, immediate availability, and a range of diameter options making cryo

Han et al[19] reported that, in all their cases, gonadal veins were harvested from female donors, highlighting that those from females particularly with a history of pregnancy were deemed superior in quality. In contrast, Nakamura et al[31] described the successful use of a gonadal artery rather than a vein from a male donor, demonstrating that a comparable strength and diameter could be achieved through vessel dilatation. However, the gonadal vein typically has a small caliber, which may render it insufficient for renal vein extension. To address this limitation, various techniques have been described, including longitudinal incision to increase the diameter of the vein, followed by circular or spiral anastomosis to achieve the desired length and improve suitability for reconstruction[2,4].

The circular technique involves forming a tubular graft from a gonadal vein segment equal in length to the circumference of the renal vein, enabling extensions of 1–3 cm. For longer reconstructions > 3 cm, the spiral technique is used where a longer gonadal vein fragment is fashioned into a spiral to provide the necessary length. Both techniques achieve a final graft caliber compatible with the renal vein and are reinforced using interrupted sutures with nonabsorbable prolene to ensure patency and durability[2]. In case 1, we used the circular cuff technique to extend the donor’s short renal vein, utilizing a syringe as a mold to facilitate the shaping of the venous graft.

Progress in kidney transplantation and immunosuppression has been greatly supported by animal research, particularly using the rat model, due to its affordability, availability of immunological tools, and suitability for microsurgery. Successful transplantation depends largely on high-quality vascular and ureteral anastomoses[32-34]. However, technical failures, especially bleeding or stenosis at vascular anastomosis sites, remain major barriers to long-term graft survival. Ensuring consistent and precise anastomosis is therefore crucial for reliable experimental outcomes[35].

The cuff technique has been successfully used in various studies focusing on kidney transplantation in rodents offering a reliable and efficient alternative to traditional suturing methods. It involves inserting the donor’s renal vein over a small, cylindrical cuff commonly made from materials like polyethylene or silicone tubing. The donor vein is everted over the cuff and secured with a ligature, creating a stable interface. This prepared end is inserted into the recipient’s corresponding vein, where it is fixed in place, establishing a secure, sutured anastomosis. This approach simplifies micro

The venous cuff technique was originally described in infragenicular bypass procedures where it was used to address the diameter mismatch between a prosthetic graft and a small-caliber distal artery. By interposing a segment of autologous vein, the technique provides a compliant transition zone that facilitates precise anastomosis and reduces the risk of technical failure associated with direct graft-to-artery suturing[37,38]. Originally introduced by Siegman[39] in 1979, the venous cuff technique underwent successive modifications by Miller et al[37] in 1984 resulting in the Miller cuff, followed by Tyrrell and Wolfe[40], who developed the St. Mary’s boot in 1991, and more recently by Nash et al[41], who described the Brighton socks variation in 2021.

In cases 2 and 3 of our series, we used the venous cuff technique as originally described by Siegman[39], adapting it for renal vein length reconstruction. A segment of the donor gonadal vein was incised longitudinally and fashioned into a circumferential patch that was sutured around the transected end of the renal vein. This configuration created a funnel-shaped venous cuff, effectively increasing the anastomotic surface area and facilitating tension-free end-to-side anastomosis with the external iliac vein. Myointimal hyperplasia is a major concern in vascular reconstruction, particularly when there is a diameter or compliance mismatch at the anastomotic site. It is considered the primary cause of restenosis or thromboembolism post-anastomosis[42]. End-to-side anastomoses involving vessels of differing calibers generate abnormal shear stress[43], while prosthetic grafts with lower compliance than native veins further disrupt flow dynamics, promoting vortex formation and intimal proliferation[44]. These hemodynamic disturbances highlight the value of the venous cuff interposition in renal transplantation, not only for extending short renal veins but also minimizing caliber mismatch and improving flow dynamics at the anastomotic site. Our report describes the use of the cuff technique for reconstructing a short renal vein in transplantation by reshaping a donor vein segment into a collar configuration, analogous to its application in distal bypass procedures.

The interposition of a venous cuff in cases of short renal veins following laparoscopic donor nephrectomy in a living-donor kidney transplantation proved to be an effective technique for vascular reconstruction. By increasing vein length and flexibility, this approach eased the tension at the anastomotic site, facilitated secure and accessible end-to-side anastomosis with the recipient’s external iliac vein, and potentially reduced the risk of postoperative vascular complications.

The authors would like to thank the surgical team and medical staff for their invaluable support during the procedures and postoperative care.

| 1. | Eng M. The role of laparoscopic donor nephrectomy in renal transplantation. Am Surg. 2010;76:349-353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 18] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Feng JY, Huang CB, Fan MQ, Wang PX, Xiao Y, Zhang GF. Renal vein lengthening using gonadal vein reduces surgical difficulty in living-donor kidney transplantation. World J Surg. 2012;36:468-472. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Hoda MR, Greco F, Reichelt O, Heynemann H, Fornara P. Right-sided transperitoneal hand-assisted laparoscopic donor nephrectomy: is there an issue with the renal vessels? J Endourol. 2010;24:1947-1952. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Troncoso P, Guzman S, Domínguez J, Ortiz AM. Renal vein extension using gonadal vein: a useful strategy for right kidney living donor harvested using laparoscopy. Transplant Proc. 2009;41:82-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Ruszat R, Wyler SF, Wolff T, Forster T, Lenggenhager C, Dickenmann M, Eugster T, Gürke L, Steiger J, Gasser TC, Sulser T, Bachmann A. Reluctance over right-sided retroperitoneoscopic living donor nephrectomy: justified or not? Transplant Proc. 2007;39:1381-1385. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 0.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Ratner LE, Ciseck LJ, Moore RG, Cigarroa FG, Kaufman HS, Kavoussi LR. Laparoscopic live donor nephrectomy. Transplantation. 1995;60:1047-1049. |

| 7. | Wolf JS Jr, Tchetgen MB, Merion RM. Hand-assisted laparoscopic live donor nephrectomy. Urology. 1998;52:885-887. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 157] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Nanidis TG, Antcliffe D, Kokkinos C, Borysiewicz CA, Darzi AW, Tekkis PP, Papalois VE. Laparoscopic versus open live donor nephrectomy in renal transplantation: a meta-analysis. Ann Surg. 2008;247:58-70. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 182] [Cited by in RCA: 169] [Article Influence: 9.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Yuzawa K, Kozaki K, Shinoda M, Fukao K. Outcome of laparoscopic living donor nephrectomy: current status and trends in Japan. Transplant Proc. 2008;40:2115-2117. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Kok NF, Weimar W, Alwayn IP, Ijzermans JN. The current practice of live donor nephrectomy in Europe. Transplantation. 2006;82:892-897. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 52] [Cited by in RCA: 50] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Mikhalski D, Hoang AD, Bollens R, Laureys M, Loi P, Donckier V. Gonadal vein reconstruction for extension of the renal vein in living renal transplantation: two case reports. Transplant Proc. 2007;39:2681-2684. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Ciudin A, Musquera M, Huguet J, Peri L, Alvarez-Vijande JR, Ribal MJ, Alcaraz A. Transposition of iliac vessels in implantation of right living donor kidneys. Transplant Proc. 2012;44:2945-2948. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Khan TT, Ahmad N, Siddique K, Fourtounas K. Implantation of Right Kidneys: Is the Risk of Technical Graft Loss Real? World J Surg. 2018;42:1536-1541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Nogueira JM, Haririan A, Jacobs SC, Weir MR, Hurley HA, Al-Qudah HS, Phelan M, Drachenberg CB, Bartlett ST, Cooper M. The detrimental effect of poor early graft function after laparoscopic live donor nephrectomy on graft outcomes. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:337-347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 44] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Alcocer F, Zazueta E, Montes de Oca J. The superficial femoral vein: a valuable conduit for a short renal vein in kidney transplantation. Transplant Proc. 2009;41:1963-1965. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Baptista-Silva JC, Medina-Pestana JO, Verissimo MJ, Castro MJ, Demuner MS, Signorelli MF. Right renal vein elongation with the inferior vena cava for cadaveric kidney transplants. An old neglected surgical approach. Int Braz J Urol. 2005;31:519-25; discussion 525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Modi P, Kadam G, Devra A. Obtaining cuff of inferior vena cava by use of the Endo-TA stapler in retroperitoneoscopic right-side donor nephrectomy. Urology. 2007;69:832-834. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Shokeir AA. Open versus laparoscopic live donor nephrectomy: a focus on the safety of donors and the need for a donor registry. J Urol. 2007;178:1860-1866. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 61] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Han DJ, Han Y, Kim YH, Song KB, Chung YS, Choi BH, Kwon TW, Cho YP. Renal vein extension during living-donor kidney transplantation in the era of hand-assisted laparoscopic living-donor nephrectomy. Transplantation. 2015;99:786-790. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Devra AK, Patel S, Shah SA. Laparoscopic right donor nephrectomy: Endo TA stapler is safe and effective. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl. 2010;21:421-425. [PubMed] |

| 21. | Molmenti EP, Varkarakis IM, Pinto P, Tiburi MF, Bluebond-Langner R, Komotar R, Montgomery RA, Jarrett T, Kavoussi LR, Ratner LE. Renal transplantation with iliac vein transposition. Transplant Proc. 2004;36:2643-2645. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Simforoosh N, Aminsharifi A, Tabibi A, Fattahi M, Mahmoodi H, Tavakoli M. Right laparoscopic donor nephrectomy and the use of inverted kidney transplantation: an alternative technique. BJU Int. 2007;100:1347-1350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kamel MH, Thomas AA, Mohan P, Hickey DP. Renal vessel reconstruction in kidney transplantation using a polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) vascular graft. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2007;22:1030-1032. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Rosenblatt GS, Conlin MJ, Soule JL, Rayhill SC, Barry JM. Right renal vein extension with recipient left renal vein after laparoscopic donor nephrectomy. Transplantation. 2006;81:135-136. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Sakai H, Ide K, Ishiyama K, Onoe T, Tazawa H, Hotta R, Teraoka Y, Yamashita M, Abe T, Hirata F, Morimoto H, Hashimoto S, Tashiro H, Ohdan H. Renal vein extension using an autologous renal vein in a living donor with double inferior vena cava: a case report. Transplant Proc. 2012;44:1446-1449. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Fallani G, Maroni L, Bonatti C, Comai G, Buzzi M, Cuna V, Vasuri F, Caputo F, Prosperi E, Pisani F, Pisillo B, Maurino L, Odaldi F, Bertuzzo VR, Tondolo F, Busutti M, Zanfi C, Del Gaudio M, La Manna G, Ravaioli M. Renal Vessel Extension With Cryopreserved Vascular Grafts: Overcoming Surgical Pitfalls in Living Donor Kidney Transplant. Transpl Int. 2023;36:11060. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Veeramani M, Jain V, Ganpule A, Sabnis RB, Desai MR. Donor gonadal vein reconstruction for extension of the transected renal vessels in living renal transplantation. Indian J Urol. 2010;26:314-316. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Paty PS, Darling RC 3rd, Lee D, Chang BB, Roddy SP, Kreienberg PB, Lloyd WE, Shah DM. Is prosthetic renal artery reconstruction a durable procedure? An analysis of 489 bypass grafts. J Vasc Surg. 2001;34:127-132. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 25] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Puche-Sanz I, Pascual-Geler M, Vázquez-Alonso F, Hernández-Vidaña AM, Flores-Martín JF, Espejo-Maldonado E, Cózar-Olmo JM. Right renal vein extension with cryopreserved external iliac artery allografts in living-donor kidney transplantations. Urology. 2013;82:1440-1443. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 0.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Nghiem DD. Spiral gonadal vein graft extension of right renal vein in living renal transplantation. J Urol. 1989;142:1525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Nakamura Y, Dan K, Miki K, Yokoyama T, Tanaka K, Ishii Y. Safe and effective elongation of a short graft and multiple renal veins using the gonadal vein (cylindrical technique) in living donor kidney transplantation. Transpl Rep. 2020;5:100047. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Mikhalski D, Wissing KM, Ghisdal L, Broeders N, Touly M, Hoang AD, Loi P, Mboti F, Donckier V, Vereerstraeten P, Abramowicz D. Cold ischemia is a major determinant of acute rejection and renal graft survival in the modern era of immunosuppression. Transplantation. 2008;85:S3-S9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 143] [Article Influence: 7.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Azuma H, Wada T, Gotoh R, Furuichi K, Sakai N, Yazawa K, Yokoyama H, Katsuoka Y, Takahara S. Significant prolongation of animal survival by combined therapy of FR167653 and cyclosporine A in rat renal allografts. Transplantation. 2003;76:1029-1036. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 0.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Spanjol J, Celić T, Jakljević T, Ivancić A, Markić D. Surgical technique in the rat model of kidney transplantation. Coll Antropol. 2011;35 Suppl 2:87-90. [PubMed] |

| 35. | Chen H, Zhang Y, Zheng D, Praseedom RK, Dong J. Orthotopic kidney transplantation in mice: technique using cuff for renal vein anastomosis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e77278. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Lauer H, Ritter J, Nachtnebel P, Simmendinger K, Lerchbaumer E, Kavaka V, Steiner D, Kolbenschlag J, Daigeler A, Heinzel JC. Use of a microvascular anastomotic coupler device for kidney transplantation in rats. Surg Open Sci. 2025;24:16-22. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Miller JH, Foreman RK, Ferguson L, Faris I. Interposition vein cuff for anastomosis of prosthesis to small artery. Aust N Z J Surg. 1984;54:283-285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 189] [Cited by in RCA: 151] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Norberto JJ, Sidawy AN, Trad KS, Jones BA, Neville RF, Najjar SF, Sidawy MK, DePalma RG. The protective effect of vein cuffed anastomoses is not mechanical in origin. J Vasc Surg. 1995;21:558-64; discussion 564. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Siegman FA. Use of the venous cuff for graft anastomosis. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1979;148:930. |

| 40. | Tyrrell MR, Wolfe JH. New prosthetic venous collar anastomotic technique: combining the best of other procedures. Br J Surg. 1991;78:1016-1017. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 75] [Cited by in RCA: 67] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Nash TM, Elahwal M, Edwards M. Adaptation of the vein cuff in distal arterial anastomosis (Brighton Sock). Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2021;103:537-538. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Lemson MS, Tordoir JH, Daemen MJ, Kitslaar PJ. Intimal hyperplasia in vascular grafts. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2000;19:336-350. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 151] [Cited by in RCA: 154] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Madras PN, Ward CA, Johnson WR, Singh PI. Anastomotic hyperplasia. Surgery. 1981;90:922-923. [PubMed] |

| 44. | Wang LC, Guo GX, Tu R, Hwang NH. Graft compliance and anastomotic flow patterns. ASAIO Trans. 1990;36:90-94. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/