Published online Mar 18, 2026. doi: 10.5500/wjt.v16.i1.111103

Revised: August 17, 2025

Accepted: October 22, 2025

Published online: March 18, 2026

Processing time: 204 Days and 24 Hours

Artificial intelligence (AI) is increasingly recognized as a transformative force in the field of solid organ transplantation. From enhancing donor-recipient matching to predicting clinical risks and tailoring immunosuppressive therapy, AI has the potential to improve both operational efficiency and patient outcomes. Despite these advancements, the perspectives of transplant professionals - those at the forefront of critical decision-making - remain insufficiently explored. To address this gap, this study utilizes a multi-round electronic Delphi approach to gather and analyses insights from global experts involved in organ transplantation. Participants are invited to complete structured surveys capturing demographic data, professional roles, institutional practices, and prior exposure to AI technologies. The survey also explores perceptions of AI’s potential benefits. Quantitative responses are analyzed using descriptive statistics, while open-ended qualitative responses undergo thematic analysis. Preliminary findings indicate a generally positive outlook on AI’s role in enhancing transplantation processes, particularly in areas such as donor matching and post-operative care. These mixed views reflect both optimism and caution among professionals tasked with integrating new technologies into high-stakes clinical workflows. By capturing a wide range of expert opinions, the findings will inform future policy development, regulatory considerations, and institutional readiness frameworks for the integration of AI into organ transplantation.

Core Tip: This study uniquely captures the collective insights of global transplantation experts on the integration of artificial intelligence, using an electronic Delphi approach to identify consensus, concerns, and implementation barriers - providing a critical foundation for ethically grounded and clinically relevant artificial intelligence adoption in organ transplantation. Initial findings show a globally positive outlook on artificial intelligence’s role in supporting transplantation processes, especially in donor matching and post-operative care areas. This should be considered with caution among professionals implementing the new technologies into high-stakes clinical practice.

- Citation: Abuyadek R, A Ghitani S, Shaaban R, Quoritem MA, Foula MS, Abdel Majid RO, Mokhtar M, Elhadi YAM, Alnagar A. Protocol for a global electronic Delphi on integrating artificial intelligence into solid organ transplantation. World J Transplant 2026; 16(1): 111103

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3230/full/v16/i1/111103.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5500/wjt.v16.i1.111103

Artificial intelligence (AI) is rapidly transforming healthcare by providing data-driven solutions to complex clinical and operational challenges. In the field of solid organ transplantation, AI applications span the entire continuum of care - from pre-transplant donor-recipient matching and organ allocation, through intraoperative support, to post-transplant monitoring and personalized immunosuppression strategies. For example, in the United Kingdom, early modelling suggests that AI-driven allocation and predictive analytics could facilitate up to 300 additional transplants annually by optimizing organ utilization and reducing discard rates[1]. In the United States, the national transplant system has partnered with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology to develop the continuous distribution framework - an AI-inspired allocation algorithm that simultaneously considers multiple patient factors and generates a transparent, weighted composite score for each candidate, aiming to improve both equity and efficiency in organ allocation[2].

Recent advances demonstrate AI’s potential to enhance transplantation beyond allocation. Machine learning models can predict nephrotoxicity or pulmonary hypertension in high-risk patients, potentially preventing the need for transplantation[2]. AI-enhanced perfusion systems can assess organ viability in real time, while predictive analytics can forecast rejection risk and graft performance, guide tailored immunosuppression regimens and reduce the need for invasive biopsies[3,4]. In histopathology, deep learning tools - such as the iBox system - have outperformed human experts in predicting long-term kidney graft outcomes, underscoring AI’s capacity to standardize and improve prognostication[5].

Despite these promising developments, significant barriers remain. The perspectives of transplantation professionals and other stakeholders on AI adoption are not well understood, and integration is complicated by ethical, regulatory, and technical challenges. These include concerns about data privacy, algorithmic bias, real-time validation, and the gov

To address this gap, we propose a global electronic Delphi (e-Delphi) study to elicit multidisciplinary expert consensus on the advantages, disadvantages, barriers, and enablers of AI integration across all organ systems and stages of transplantation. This protocol seeks to capture diverse perspectives from clinicians, surgeons, data scientists, and ethicists worldwide, with the goal of identifying areas of agreement and divergence on key themes such as ethics, regulatory readiness, technical feasibility, and implementation strategies. The resulting consensus will inform a globally relevant readiness framework for AI adoption in transplantation practice.

This study will employ a global e-Delphi design - a structured, iterative process that uses multiple rounds of anonymous online surveys to gather and refine expert opinion until consensus is achieved. The design follows the Conducting and REporting DElphi Studies checklist to ensure methodological transparency and rigor[7].

Eligible participants will include clinicians, surgeons, data scientists, and ethicists worldwide with demonstrated expertise in solid organ transplantation or AI applications in healthcare. All participants must have at least five years of professional experience in relevant roles and be actively engaged in transplantation-related practice, research, policy, or governance. To ensure a comprehensive and multidisciplinary perspective, the study will seek representation from all major organ transplant domains (kidney, liver, heart, lung, pancreas) and across diverse healthcare systems and geo

A purposive and snowball sampling approach will be used to recruit participants with varied geographic, subspecialty, and gender backgrounds. After round 1, demographic distribution will be reviewed, and targeted invitations will be sent to address underrepresentation in specific regions, clinical disciplines, or demographic groups, thereby reducing selection bias. A minimum of 20 participants per round is targeted, in line with prior Delphi studies, with an aim to expand to 30-50 participants to strengthen reliability and generalizability.

The survey comprises four main sections and includes both 5-point Likert-scale items (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neutral, 4 = agree 5 = strongly agree) and open-ended questions. Sections are: Consent and eligibility: Participants must provide informed consent and confirm active involvement in organ transplantation; demographics: Age, gender, nationality, country of practice, and institution type (public, private, or mixed). Professional experience: Role, years of experience, annual transplant case volumes, types of transplants performed (living donor, deceased donor, or both), matching process (local criteria, predictive model, or centralized authority), and decision-making responsibility (individual surgeon vs multidisciplinary team). AI perceptions and usage: Self-reported familiarity with AI tools (e.g., natural language processing, machine learning, robotic surgery); perceived utility in radiology, pathology, and immunosuppression management; institutional, legal and political readiness to invest in AI; perceived advantages, disadvantages, enablers (e.g., institutional support); barriers (e.g., data privacy concerns, algorithmic bias, lack of legal frameworks); and satisfaction with current systems compared to potential AI-enhanced systems. Face validity of the survey was established through review by three transplant AI experts. A formal Content Validity Index was not calcu

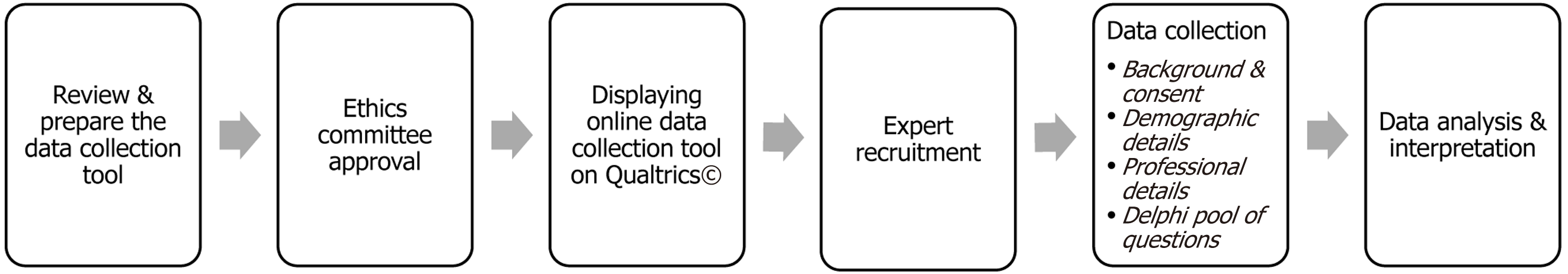

Surveys will be administered via Qualtrics© (hosted on secure servers at Utah State University) over two planned rounds. Each round will remain open for approximately 3-4 weeks. Iterative feedback, including anonymized summaries of group responses, will be shared between rounds to allow participants to reflect and, if desired, modify their responses. An individualized but de-linked token system will preserve anonymity during iterative feedback. Figure 1 illustrates the overall study process flow, including participant recruitment, eligibility confirmation, survey rounds, feedback loops, and consensus determination.

For quantitative analysis, descriptive statistics will be used to summarize demographic characteristics and item responses. Consensus will be defined a priori as > 70% of participants rating 4-5 on a Likert item, with an interquartile range ≤ 1. A 70% agreement level has been deemed appropriate in numerous Delphi studies, setting a historical standard for rigor and reliability in expert consensus-building. For open-ended responses will be subjected to thematic analysis by two independent coders. Inter-coder reliability will be assessed, and discrepancies will be resolved by consensus to ensure validity.

In the first round (n = 11), most respondents were male (64%), affiliated with public institutions (73%), and involved primarily in live donor transplantation (55%). Notably, 55% reported that donor-recipient matches were determined by the patient or their family, while 45% indicated centralized matching systems. Commonly quoted benefits of AI included enhanced precision in donor-recipient matching, early rejection detection, and improved evaluation of organ viability. While main concerns focused on data governance, potential algorithmic bias, and unclear accountability in clinical decision-making (Table 1).

| Variable | Total (n = 11) |

| Gender | |

| Male | 7 (64) |

| Age (minimum-maximum, mean ± SD) | 31-61, 42 ± 9 |

| Nationality | |

| Egypt | 6 (55) |

| Italy | 2 (18) |

| Belgium | 1 (9) |

| Greece | 1 (9) |

| Netherlands | 1 (9) |

| Country you are currently working | |

| Egypt | 4 (36) |

| Italy | 2 (18) |

| Belgium | 1 (9) |

| Greece | 1 (9) |

| Kuwait | 1 (9) |

| Netherlands | 1 (9) |

| United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland | 1 (9) |

| Type of practice in organ transplantation | |

| Public only | 8 (73) |

| Both (public and private) | 3 (27) |

| Solid organ transplant expertise specific data | |

| Transplant nephrologist | 4 (36) |

| Transplant ethics/social support | 2 (18) |

| Transplant hepatobiliary surgeon | 2 (18) |

| Transplant pathologist | 1 (9) |

| Transplant coordinator | 1 (9) |

| Transplant hepatologist | 1 (9) |

| Years of experience (solid organ transplantation specific experience) | |

| < 5 years | 2 (18) |

| 5-10 years | 2 (18) |

| 10-15 years | 3 (27) |

| 15-20 years | 2 (18) |

| > 20 years | 2 (18) |

| Approximate number of transplant cases you were involved in (assessed) within your career in solid organ transplantation | |

| < 50 transplant cases | 5 (45.5) |

| 100-150 transplant cases | 1 (9) |

| > 200 transplant cases | 5 (45.5) |

| Type of solid organ transplantation you were involved in within your institution | |

| Live only | 6 (55) |

| Cadaveric only | 1 (9) |

| Both | 4 (36) |

| Size of solid organ transplantation within your current workplace (institution) = average number of cases/year (minimum-maximum, median) | 10-350, 117 |

| In your current workplace/health system, who is responsible for recommending the matching donor | |

| Patient living related/ unrelated donor | 6 (55) |

| A country wide/geographical system | 5 (45) |

| In your current workplace/health system, the donor recipient matching process is done through | |

| Criteria based on clinical scores | 5 (45) |

| An authority managed on a central level of specific geographical area | 2 (18) |

| An authority managed on a central level of specific geographical area, criteria based on clinical scores | 2 (18) |

| An authority managed on a central level of specific geographical area, criteria based on clinical scores, predictive model | 1 (9) |

| Predictive model | 1 (9) |

| In your current workplace/health system, who is responsible for the final decision for accepting potential donor | |

| Surgeon/ physician | 7 (64) |

| MDT of related specialties | 4 (36) |

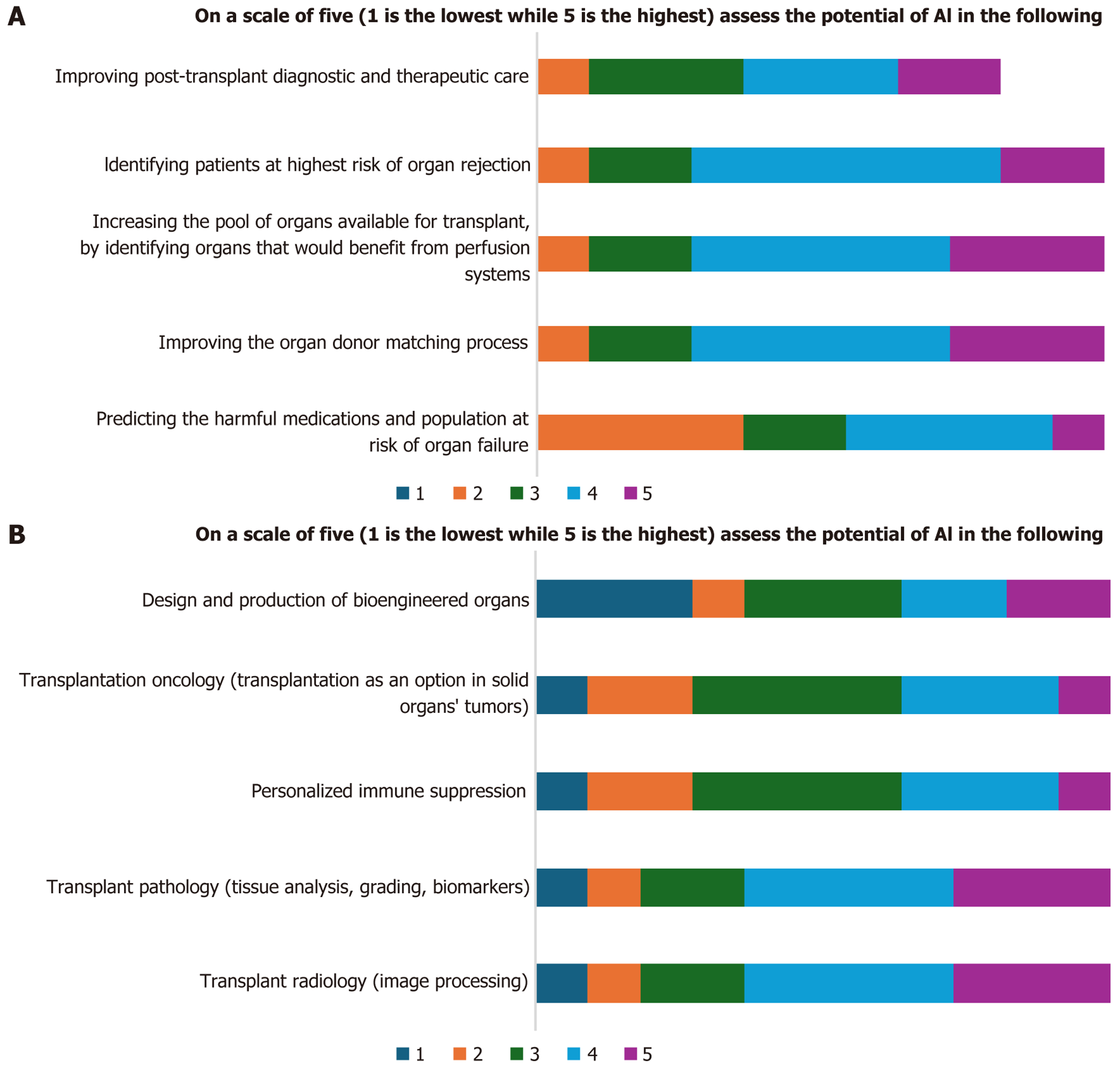

Experts expressed high scores in Likert scales for the potential uses of AI in organ transplantation process as clarified in Figure 2A. In AI applications, they expressed the potential uses of AI in transplant pathology and radiology, however, low and neutral scores for used of AI in designing and production of bioengineered organs, transplantation oncology, and personalized immune suppression (Figure 2B).

The most reported concerns regarding the use of AI in the process of solid organ donor recipient matching was the clinical validity and reliability of the AI model used and the data privacy and security. Six preliminary responses think that their institutes should invest in comprehensive AI technology to manage the process of solid organ transplantation, particularly to improve practice, save cost, improve outcomes and uncover new knowledge.

AI is increasingly recognized as a transformative enabler across all phases of solid organ transplantation, from donor-recipient matching and organ allocation to intraoperative support and post-transplant monitoring. In the pre-transplant phase, AI algorithms, based on neural networks and deep learning, can integrate complex clinical, demographic, and immunological data to guide organ allocation more effectively than traditional human assessment[8]. Examples include the United Network for Organ Sharing/Massachusetts Institute of Technology continuous distribution framework, which simultaneously evaluates multiple allocation factors to optimize fairness and efficiency[9]. During surgery, AI-powered robotic systems can enhance precision and reduce technical error, thereby improving graft outcomes[10,11]. Post-transplant, machine learning models have been used to predict graft survival, rejection, and drug toxicity based on multidimensional patient data, enabling earlier interventions and more tailored immunosuppression[5]. The iBox prediction system, for instance, has demonstrated superior accuracy over transplant physicians in predicting long-term kidney graft failure, supporting its potential role as a validated “companion” decision-support tool to reduce inter-clinician variability[12]. Across organ types, such tools offer opportunities to improve diagnostic accuracy, standardize decision-making, and support proactive complication management, ultimately streamlining workflows and improving patient outcomes[13].

Despite these benefits, integration of AI into clinical transplantation workflows presents several important challenges. First, the limited size and quality of transplant datasets confined to single-center studies can restrict generalizability and risk model overfitting. Collaborative multi-center studies and data-sharing initiatives, such as the NephroCAGE consortium, demonstrate that pooling diverse datasets can strengthen model robustness while privacy-preserving techniques like federated learning address regulatory constraints (e.g., General Data Protection Regulation, Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act)[14]. Second, algorithmic bias remains a concern as unbalanced training data may perpetuate inequities in organ allocation or prognostication across demographic groups[8,15]. Mitigation strategies include bias audits, ensuring diverse representation in training datasets, and stratifying performance metrics across subpopulations during validation[8]. Third, “black-box” algorithms may hinder clinician trust; therefore, explainable AI methods or interpretable outputs are essential for transparency and accountability[16].

A further barrier is the lack of prospective, real-time validation[2,17]. Many AI tools in transplantation are validated retrospectively; few have been embedded in real-world workflows or tested in randomized or prospective trials to demonstrate clinical utility[18]. Addressing this “last mile” requires pilot deployments where AI outputs are reviewed alongside human decision-making, and ongoing model re-validation to prevent performance drift. Governance frameworks must evolve accordingly. AI should function as a supportive, not autonomous, decision-making tool, main

Our Delphi study addresses these opportunities and challenges in a systematic, consensus-driven manner. Unlike prior reviews, such as Loupy et al[5], Bae et al[6], and Alamgir et al[19] which primarily summarize existing applications or highlight conceptual considerations, our study seeks to generate expert-agreed guidance across all organ systems and AI application domains. By engaging a multidisciplinary panel including transplant clinicians, surgeons, data scientists, and ethicists across multiple regions, the Delphi process will refine priorities, identify feasible solutions such as model validation standards, governance principles, and inform a globally relevant readiness framework for AI integration in transplantation. This consensus-oriented approach provides greater granularity than literature syntheses alone and offers practical recommendations for safe, equitable, and effective implementation.

We proposed to have at least twenty experts per round and at least two rounds of consensus until reaching 70% agreement. In the first round, we were able to collect the responses of 11 experts as clarified in the results, however, additional rounds are needed to enhance data collection and consensus building. Preliminary results reveal both optimism and caution among transplantation professionals regarding AI. While its potential to enhance clinical and operational efficiency is acknowledged, ethical, regulatory, and infrastructural concerns persist. Further Delphi rounds will aim to refine consensus and inform the development of a globally relevant readiness assessment for AI integration in solid organ transplantation.

This protocol addresses the global need for an e-Delphi study to explore the potential uses of AI in solid organ transplantation; however, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the preliminary round was limited in the number of respondents (n = 11), and additional rounds are required to achieve the targeted panel size and build robust consensus. Second, as with many Delphi studies, the use of snowball sampling was intended to increase access to qualified transplantation experts across diverse regions and specialties, yet this approach may introduce selection bias. Future rounds will need to actively mitigate this risk by targeting underrepresented geographic areas, clinical disciplines, and professional backgrounds. Finally, while this protocol outlines a structured, consensus-driven methodology, the findings will reflect expert opinion at a given point in time and should be periodically revisited as AI technologies, regulatory frameworks, and transplantation practices evolve.

This protocol outlines a global e-Delphi study designed to assess expert consensus on integrating AI into solid organ transplantation across all organ systems and phases of care. By engaging a multidisciplinary and geographically diverse panel, the study aims to identify enablers, barriers, and practical solutions for safe, equitable, and effective AI adoption. Achieving such consensus is critical to ensuring that AI is implemented not only in a technologically sound manner, but also in a way that aligns with ethical imperatives, regulatory requirements, and patient-centered values.

We invite transplantation centers, clinical and surgical experts, data scientists, ethicists, and professional societies worldwide to participate in the subsequent Delphi rounds. Your expertise will help shape a globally relevant readiness framework, inform governance policies, and guide the responsible integration of AI into transplantation practice. We also encourage participants to share and disseminate the survey tool within their professional networks, to promote broad, informed engagement and to ensure that the resulting recommendations reflect the collective wisdom of the global tran

| 1. | Ugail H, Abubakar A, Elmahmudi A, Wilson C, Thomson B. The use of pre-trained deep learning models for the photographic assessment of donor livers for transplantation. Art Int Surg. 2022;2:101-119. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 2. | Deshpande R. Smart match: revolutionizing organ allocation through artificial intelligence. Front Artif Intell. 2024;7:1364149. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Adedinsewo D, Hardway HD, Morales-Lara AC, Wieczorek MA, Johnson PW, Douglass EJ, Dangott BJ, Nakhleh RE, Narula T, Patel PC, Goswami RM, Lyle MA, Heckman AJ, Leoni-Moreno JC, Steidley DE, Arsanjani R, Hardaway B, Abbas M, Behfar A, Attia ZI, Lopez-Jimenez F, Noseworthy PA, Friedman P, Carter RE, Yamani M. Non-invasive detection of cardiac allograft rejection among heart transplant recipients using an electrocardiogram based deep learning model. Eur Heart J Digit Health. 2023;4:71-80. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Ruiz Morales J, Nativi-nicolau J, Jang J, Patel P, Yip D, Leoni-moreno J, Goswami R. Artificial Intelligence 12 Lead ECG Based Heart Age Estimation and 1-year Outcomes After Heart Transplantation. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2022;41:S213. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Loupy A, Preka E, Chen X, Wang H, He J, Zhang K. Reshaping transplantation with AI, emerging technologies and xenotransplantation. Nat Med. 2025;31:2161-2173. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Bae S, Massie AB, Caffo BS, Jackson KR, Segev DL. Machine learning to predict transplant outcomes: helpful or hype? A national cohort study. Transpl Int. 2020;33:1472-1480. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 6.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Jünger S, Payne SA, Brine J, Radbruch L, Brearley SG. Guidance on Conducting and REporting DElphi Studies (CREDES) in palliative care: Recommendations based on a methodological systematic review. Palliat Med. 2017;31:684-706. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 460] [Cited by in RCA: 1297] [Article Influence: 144.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Arjmandmazidi S, Heidari HR, Ghasemnejad T, Mori Z, Molavi L, Meraji A, Kaghazchi S, Mehdizadeh Aghdam E, Montazersaheb S. An In-depth overview of artificial intelligence (AI) tool utilization across diverse phases of organ transplantation. J Transl Med. 2025;23:678. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Kasiske BL, Pyke J, Snyder JJ. Continuous distribution as an organ allocation framework. Curr Opin Organ Transplant. 2020;25:115-121. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Jiang F, Jiang Y, Zhi H, Dong Y, Li H, Ma S, Wang Y, Dong Q, Shen H, Wang Y. Artificial intelligence in healthcare: past, present and future. Stroke Vasc Neurol. 2017;2:230-243. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1189] [Cited by in RCA: 1611] [Article Influence: 179.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Benjamens S, Dhunnoo P, Meskó B. The state of artificial intelligence-based FDA-approved medical devices and algorithms: an online database. NPJ Digit Med. 2020;3:118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 418] [Cited by in RCA: 560] [Article Influence: 93.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Divard G, Raynaud M, Tatapudi VS, Abdalla B, Bailly E, Assayag M, Binois Y, Cohen R, Zhang H, Ulloa C, Linhares K, Tedesco HS, Legendre C, Jouven X, Montgomery RA, Lefaucheur C, Aubert O, Loupy A. Comparison of artificial intelligence and human-based prediction and stratification of the risk of long-term kidney allograft failure. Commun Med (Lond). 2022;2:150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Olawade DB, Marinze S, Qureshi N, Weerasinghe K, Teke J. The impact of artificial intelligence and machine learning in organ retrieval and transplantation: A comprehensive review. Curr Res Transl Med. 2025;73:103493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Schapranow MP, Bayat M, Rasheed A, Naik M, Graf V, Schmidt D, Budde K, Cardinal H, Sapir-Pichhadze R, Fenninger F, Sherwood K, Keown P, Günther OP, Pandl KD, Leiser F, Thiebes S, Sunyaev A, Niemann M, Schimanski A, Klein T. NephroCAGE-German-Canadian Consortium on AI for Improved Kidney Transplantation Outcome: Protocol for an Algorithm Development and Validation Study. JMIR Res Protoc. 2023;12:e48892. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Elendu C, Amaechi DC, Elendu TC, Jingwa KA, Okoye OK, John Okah M, Ladele JA, Farah AH, Alimi HA. Ethical implications of AI and robotics in healthcare: A review. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023;102:e36671. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 108] [Cited by in RCA: 120] [Article Influence: 40.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 16. | Briceño J, Calleja R, Hervás C. Artificial intelligence and liver transplantation: Looking for the best donor-recipient pairing. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2022;21:347-353. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Clement J, Maldonado AQ. Augmenting the Transplant Team With Artificial Intelligence: Toward Meaningful AI Use in Solid Organ Transplant. Front Immunol. 2021;12:694222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 3.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Størset E, Åsberg A, Skauby M, Neely M, Bergan S, Bremer S, Midtvedt K. Improved Tacrolimus Target Concentration Achievement Using Computerized Dosing in Renal Transplant Recipients--A Prospective, Randomized Study. Transplantation. 2015;99:2158-2166. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 64] [Cited by in RCA: 92] [Article Influence: 9.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Alamgir A, Hussein H, Abdelaal Y, Abd-Alrazaq A, Househ M. Artificial Intelligence in Kidney Transplantation: A Scoping Review. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2022;294:254-258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Article Influence: 0.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/