Published online Feb 19, 2026. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v16.i2.112996

Revised: August 20, 2025

Accepted: October 21, 2025

Published online: February 19, 2026

Processing time: 171 Days and 16.5 Hours

Depressive and anxiety symptoms among adolescents have become significant public health concerns, yet comprehensive studies examining their prevalence and associated factors are limited. Functional constipation (FC), as a common gas

To examine depressive/anxiety symptoms prevalence and their associations with FC and other potential risk factors among adolescents in Lianyungang, Jiangsu Province, China.

We conducted a cross-sectional survey of 22925 adolescents using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 and Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 for depressive and anxiety symptoms, respectively. FC was evaluated using the Rome IV criteria, and social support using the Perceived Social Support Scale.

Depressive symptoms were reported by 16.0%, anxiety symptoms by 24.1%, with 13.1% experiencing both. Among the total group, 27.5% reported mild, 10.0% moderate, 4.0% moderately severe, and 2.0% severe depressive symptoms, while 23.0% reported mild, 7.2% moderate, and 3.8% severe anxiety symptoms. Female sex, smoking, FC, parental conflict, lower household income, lower levels of physical activity, and longer weekly electronic device use time were identified as significant risk factors for depressive and anxiety symptoms (all P < 0.05), while age and body mass index were identified as additional significant risk factors for anxiety symptoms (all P < 0.05). In contrast, received support was identified as a significant protective factor against depressive and anxiety symptoms.

Targeting modifiable risk factors (physical activity, smoking, excessive device use) and improving mental health support access are priorities to address the high prevalence of depression and anxiety symptoms.

Core Tip: This large-scale cross-sectional study of 22925 Chinese adolescents reveals concerning rates of depression (16.0%) and anxiety (24.1%) symptoms, with approximately 10% reporting moderate to severe symptoms. The study uniquely identifies functional constipation as a significant risk factor for both conditions, potentially reflecting brain-gut axis dysfunction. Female sex, smoking, parental conflict, lower household income, reduced physical activity, and excessive electronic device use were also identified as risk factors, while social support emerged as protective. These findings underscore the urgent need for comprehensive screening and targeted interventions addressing modifiable risk factors to improve adolescent mental health outcomes.

- Citation: Yang HD, Zhang J, Yang M, Luan LS, Liu JJ, Zhang XB. Prevalence, severity, and risk factors for depressive and anxiety symptoms among adolescents: A cross-sectional study. World J Psychiatry 2026; 16(2): 112996

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v16/i2/112996.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v16.i2.112996

Depression and anxiety disorders are among the top 25 leading causes of disability worldwide, and thus are major public health concerns[1,2]. Adolescence is a critical period of psychological development, and both depressive and anxiety symptoms are increasing in prevalence among this age group, hampering academic performance and socialization, and potentially reducing quality of life in adulthood[3-5]. Further, symptoms of depression and anxiety often coexist, and are mutually reinforcing, thereby exacerbating the burden of illness[6,7]. Despite the availability of effective treatments, adolescents are seldom diagnosed and treated unless necessitated by a serious precipitating incident[8-10], highlighting the importance of screening for early identification and intervention.

According to the World Health Organization, the worldwide prevalence of depressive disorders among individuals 10 years to 19 years of age was 4.7% in 2019, and has risen further since due to the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic and associated countermeasures[11,12]. However, prevalence differs considerably among regions, reflecting the influences of geography, cultural background, socioeconomic status, and potentially also different survey instruments[13-16]. Nonetheless, it is generally agreed that depressive symptoms constitute a major mental health challenge among adolescents due to the increased risks of self-injury, suicidal thoughts, and even suicidal behaviors[17-19].

Anxiety symptoms are also frequent among adolescents. For example, a prevalence rate of 37.89% was reported in Nepal[20], while a survey in Vietnam reported moderate anxiety among 22.8% of respondents and severe anxiety among 7.32%[21]. Similar or higher rates have been reported outside of Asia, including 39.1% in Morocco[22], 61.8% in Peru[23], and 31.9% in the United States[24]. Further, psychosocial stressors experienced during adolescence have been identified as key factors compromising short- and long-term mental health[25,26]. Further, symptoms of anxiety and depression are frequently comorbid, and adolescents with comorbid anxiety and depressive symptoms are more prone to unintentional injuries, premature and unsafe behaviors, smoking, poor diet, and sleep disorders[27].

Depressive and anxiety symptoms in adolescents are influenced by biological traits, social factors, the family environment, and presumably by various interactions among genes and the environment[28]. Indeed, several genetic factors and brain biomarkers have been linked to adolescent mental illness[29,30]. Psychological factors strongly implicated in depressive and anxiety symptom onset among adolescents include low self-esteem, negative thought patterns, and poor coping skills[31-33], while influencing factors related to the family environment include the parent–child relationship, the parental relationship, family economic status, and perception of parental support[22,34,35]. Further, social and environmental factors related to depression and anxiety include peer relationships, academic pressures, childhood trauma, physical activity time, interpersonal conflicts, bullying, and the excessive use of electronic devices[36-39]. Functional constipation (FC), as a common gastrointestinal disorder, is also closely related to mental health through the gut-brain axis[40,41]. Research indicates that gut microbiota influences central nervous system function through the gut-brain axis, including emotion regulation and stress response[42]. Therefore, FC may be an important correlate of depressive and anxiety symptoms in adolescents.

We speculated that FC, gender, smoking, perceived support, parental relationship, family economic status, physical activity level, weekly electronic device usage time (WEDUT), and local civic environment (urban vs suburban) may be significant predictors of depression and anxiety symptoms in adolescents. The aims of the current study were to: (1) Evaluate the prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms among adolescents in Lianyungang, Jiangsu Province, China; (2) Assess the severity distribution of depressive and anxiety symptoms; and (3) Explore whether FC influences depressive and anxiety symptoms among adolescents in addition to these other aforementioned potential risk factors. To the best of our knowledge, this is one of the larger-scale investigations of adolescent depressive and anxiety symptom prevalence in Lianyungang area since the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic, providing important data for under

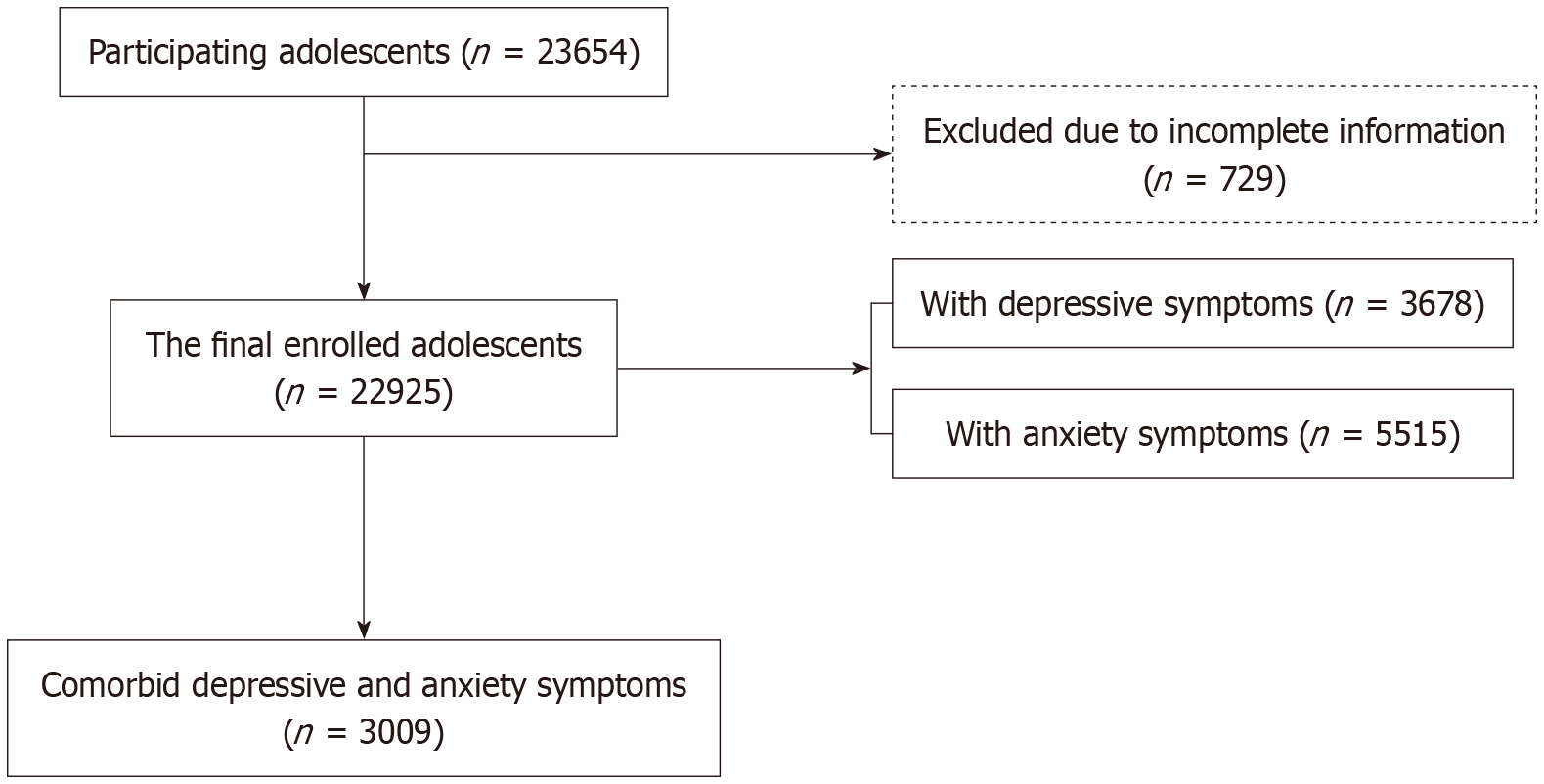

We conducted a cross-sectional survey of depressive and anxiety symptoms among adolescents in Lianyungang, Jiangsu Province, China, between September and November 2023. Students from eight secondary schools encompassing both junior levels (grades 7 to 9) and senior levels (grades 10 to 12) were invited to complete the survey using the Wenjuanxing online platform (https://www.wjx.cn/app/survey.aspx). These eight secondary schools were selected using a stratified sampling method, considering representativeness of school type and geographic location (urban/suburban). We first stratified the secondary schools in the region by type and location, then randomly selected schools from each stratum. Prior to completing the online survey, students were provided with a detailed guide describing the purpose of the survey and assurances that the data collected was confidential and anonymous (including to parents and teachers). Students also had the opportunity to withdraw from the survey at any point, and that if they decided to do so after the survey was completed, they could still contact the research team and request their data be removed. Figure 1 shows the adolescent recruitment process flowchart.

The project was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Fourth People’s Hospital of Lianyungang City, approval No. 2023 LSYYXLL-P21. Written informed consent was obtained from parents/guardians of all participating students, and verbal assent was obtained from the students themselves before the investigation. The schools and teachers were also informed and provided consent. All signed consent forms were kept by the schools.

The research team designed a self-reported, semi-structured questionnaire to collect sociodemographic information including age, gender, height, weight, smoking status (yes/no), grade and class, single-parent family status (yes/no), parental relationship (harmony/moderate/conflict), annual household income (better/good/fair), physical activity level (high/medium/Low), and WEDUT (high/moderate/Low). Smoking status was assessed through the question “Do you currently smoke?” with “yes” defined as having smoked (including E-Cigarette) on at least 1 day during the past 30 days, otherwise classified as “no”[43]. Parental relationship was evaluated through the question “How would you describe the relationship between your parents?” with three classification levels: Harmony (referring to parents having an amicable relationship with minimal disputes), moderate (referring to parents having a good relationship but with occasional disagreements), and conflict (referring to parents having a tense relationship with frequent arguments or confrontations). Annual household income was categorized as “fair” if under 100000 yuan, “good” if 100000 yuan to 200000 yuan, and “better” if exceeding 200000 yuan. The categorization was based on the 2022 data from Lianyungang Bureau of Statistics (https://tjj.lyg.gov.cn). Similarly, physical activity level per week was classified as “low” if less than 2 hours, “medium” if 2 hours to 6 hours, and “high” if over 6 hours, while WEDUT was categorized as “high” if over 5 hours per week, “moderate” if 2 hours to 5 hours weekly, and “low” if less than 2 hours weekly.

Depressive symptoms were assessed using the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)[44], which includes nine items based on the diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual-IV. The occurrence and frequency of symptoms experienced within the last two weeks are assessed using a quartile grading scale as follows: 0 for “not at all”, 1 for “several days”, 2 for “more than half the days”, and 3 for “nearly every day”. The total score (ranging from 0 to 27) gauges the severity of depression, with scores of 0-4 indicating none or minimal symptoms and scores of 5-9 indicating mild, 10-14 moderate, 15-19 moderately severe, and 20-27 severe depression symptoms. The PHQ-9 demonstrates excellent reliability and validity within the Chinese population and so is widely utilized for the evaluation of depressive symptoms[45]. In this study, a total score of 10 points was used as the cut-off threshold for distinguishing students with and without depressive symptoms[46,47].

We employed the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item (GAD-7) scale to assess anxiety symptoms. This instrument consists of seven items that query respondents about the frequency of anxiety symptoms experienced over the preceding two weeks utilizing a four-point scoring system as follows: 0 for “not at all”, 1 for “several days”, 2 for “more than half the days”, and 3 for “nearly every day”. Again, a total score of 0-4 denotes minimal symptoms while 5-9 indicates mild, 10-14 moderate, and 15-21 severe anxiety symptoms[48]. The GAD-7 has demonstrated good reliability and validity for the assessment of anxiety symptoms in the Chinese adolescent population[49]. A cut-off value of 7 points was set to distinguish students with and without anxiety symptoms[50]. In this study, comorbidity of depressive and anxiety symptoms was defined as simultaneously meeting both the criteria for depressive symptom screening (PHQ-9 ≥ 10) and anxiety symptoms screening (GAD-7 ≥ 7).

The Perceived Social Support Scale (PSSS) was employed to evaluate the social support perceived by students. This instrument consists of 12 items, each scored on a 7-point Likert scale from “strongly disagree” (1 point) to “strongly agree” (7 points) based on their experiences in the preceding month. A higher cumulative score denotes increased perceived social support. The PSSS was stratified into subscales indicating levels of family support, support from friends, and support by others.

FC was diagnosed according to Rome IV criteria[51], which requires the presence of two or more core symptoms, two exclusion criteria within the last three months, and symptom onset at least six months prior. The diagnosis of FC was also excluded if there was a previous diagnosis of constipation attributed to another cause.

All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 23.0. Sample size calculation and effect size estimation were conducted using the locally installed G*Power 3 software (version 3.1.9.7, Heinrich Heine University Düsseldorf), not the online version, with an alpha error probability of 0.05 and statistical power (1-β) of 0.80. Continuous variables such as age, height, weight, and psychometric scale scores (PHQ-9, GAD-7, and PSSS) are presented as mean and SD, while categorical variables such as gender, smoking status, geographical region, income level, and parental relationship are expressed as frequency or percentage. Continuous variables were compared by Student’s t-test or independent samples t-test and categorical variables by the χ2 test. Potential risk factors were first assessed by univariate analysis and those deemed significant were included in a binary logistic regression model to identify independent risk factors for depression or anxiety symptoms among adolescents. A two-tailed P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all tests.

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

A total of 23654 questionnaires were collected, of which 729 (3.08%) were excluded for missing information on gender (28, 0.12%), age (88, 0.37%), height (323, 1.37%), weight (141, 0.6%), or multiple items missing in either the PHQ-9 or GAD-7 (149, 0.63%). Ultimately, 22,925 completed questionnaires were collected and included in the analysis. Of the 22925 adolescents included, 52.8% (n = 12115) were male, 47.2% (n = 10810) were female, and age ranged from 11 years to 19 years (mean 14.27 ± 1.52 years). The majority were junior high school students (n = 17780, 77.6% vs n = 5145, 22.4%). Within this total population, 11.0% (n = 2522) reported smoking and 7.8% (n = 1780) had FC.

As shown in Table 1, age, gender, region of residence, smoking status, PSSS total score and each subscale score, parental relationship, annual household income, WEDUT, and FC differed significantly between adolescents with and without depressive symptoms and between adolescents with and without anxiety symptoms (all P < 0.05). Education level (P = 0.475) and body mass index (BMI) (P = 0.109) did not differ between adolescents with and without depressive symptoms, but did differ significantly between adolescents with and without anxiety symptoms (all P < 0.05).

| Characteristic | Depressive symptoms | Anxiety symptoms | ||||

| With (n = 3678) | Without (n = 19247) | P value | With (n = 5515) | Without (n = 17410) | P value | |

| Age (year), mean ± SD | 14.36 ± 1.42 | 14.25 ± 1.54 | < 0.001 | 14.45 ± 1.46 | 14.21 ± 1.54 | < 0.001 |

| Sex | < 0.001 | - | < 0.001 | |||

| Male | 1548 (12.8) | 10567 (87.2) | 2395 (19.8) | 9720 (80.2) | ||

| Female | 2130 (19.7) | 8680 (80.3) | 3120 (28.9) | 7690 (71.1) | ||

| Educational levels | 0.475 | - | < 0.001 | |||

| Junior high school | 2836 (16.0) | 14944 (84.0) | 4091 (23.0) | 13689 (77.0) | ||

| Senior high school | 842 (16.4) | 4303 (83.6) | 1424 (27.7) | 3721 (72.3) | ||

| Regions | < 0.001 | - | < 0.001 | |||

| Urban | 3183 (15.4) | 17545 (84.6) | 4856 (23.4) | 15872 (76.6) | ||

| Suburban | 495 (22.5) | 1702 (75.5) | 659 (30.0) | 1538 (70.0) | ||

| BMI (kg/m2), mean ± SD | 21.13 ± 3.89 | 21.02 ± 3.78 | 0.109 | 21.19 ± 3.86 | 20.99 ± 3.78 | 0.001 |

| Smoking | < 0.001 | - | < 0.001 | |||

| Yes | 566 (22.4) | 1956 (77.6) | 772 (30.6) | 1750 (69.4) | ||

| No | 3112 (15.3) | 17291 (84.7) | 4743 (23.2) | 15660 (76.8) | ||

| PSSS total scores, mean ± SD | 49.50 ± 14.92 | 66.14 ± 14.49 | < 0.001 | 52.21 ± 14.71 | 67.04 ± 14.39 | < 0.001 |

| Family support | 15.70 (5.94) | 22.23 (5.37) | < 0.001 | 16.85 (5.87) | 22.56 (5.31) | < 0.001 |

| Friend support | 17.46 (5.97) | 21.86 (5.18) | < 0.001 | 18.03 (5.66) | 22.15 (5.15) | < 0.001 |

| Significant others | 16.34 (5.59) | 22.04 (5.10) | < 0.001 | 17.33 (5.42) | 22.33 (5.08) | < 0.001 |

| Parental relationship | < 0.001 | - | < 0.001 | |||

| Harmony | 1604 (10.0) | 14412 (90.0) | 2742 (17.1) | 13274 (82.9) | ||

| Moderate | 1647 (27.7) | 4303 (72.3) | 2277 (38.3) | 3673 (61.7) | ||

| Conflict | 427 (44.5) | 532 (55.5) | 496 (51.7) | 463 (48.3) | ||

| Annual household income | < 0.001 | - | < 0.001 | |||

| Better | 1169 (11.7) | 8851 (88.3) | 1882 (18.8) | 8138 (81.2) | ||

| Good | 1954 (17.7) | 9068 (82.3) | 2927 (26.6) | 8095 (73.4) | ||

| Fair | 555 (29.5) | 1328 (70.5) | 706 (37.5) | 1177 (62.5) | ||

| Physical activity level | < 0.001 | - | < 0.001 | |||

| High | 502 (11.5) | 3866 (88.5) | 804 (18.4) | 3564 (81.6) | ||

| Medium | 1274 (14.3) | 7666 (85.7) | 1936 (21.7) | 7004 (78.3) | ||

| Low | 1902 (19.8) | 7715 (80.2) | 2775 (28.9) | 6842 (71.1) | ||

| WEDUT | < 0.001 | - | < 0.001 | |||

| High | 1014 (26.0) | 2882 (74.0) | 1365 (35.0) | 2531 (65.0) | ||

| Moderate | 1330 (17.0) | 6477 (83.0) | 2048 (26.2) | 5759 (73.8) | ||

| Low | 1334 (11.9) | 9888 (88.1) | 2102 (18.7) | 9120 (81.3) | ||

| FC | < 0.001 | - | < 0.001 | |||

| Yes | 384 (21.6) | 1396 (78.4) | 540 (30.3) | 1240 (69.7) | ||

| No | 3294 (15.6) | 17851 (84.4) | 4975 (23.5) | 16170 (76.5) | ||

Depressive symptoms were reported by 16.0% and anxiety symptoms by 24.1% of the total cohort, with females reporting significantly higher rates of both depressive symptoms (19.7% vs 12.8% of males, χ2 = 203.471, P < 0.001) and anxiety symptoms (28.9% vs 19.8% of males, χ2 = 258.557, P < 0.001). Additionally, among participants, 21.6% of those with self-reported depressive symptoms have FC, compared to 15.6% without FC (χ2 = 43.805, P < 0.001). Similarly, 30.3% of participants with self-reported anxiety symptoms have FC compared to 23.5% without FC (χ2 = 41.665, P < 0.001).

According to PHQ-9 scores, 27.5% of the total cohort reported mild, 10.0% moderate, 4.0% moderately severe, and 2.0% severe depressive symptoms, while according to GAD-7 scores, 23.0% of the total cohort reported mild, 7.2% moderate, and 3.8% severe anxiety symptoms (Table 2). Among the adolescents in this study, 13.1% presented with comorbid depressive and anxiety symptoms. Mean scores for subgroups are also presented in Table 2.

| Characteristic | Depressive symptoms | Anxiety symptoms | Comorbid depressive and anxiety symptoms | ||

| n (%) | mean ± SD | n (%) | mean ± SD | n (%) | |

| Minimal | 12941 (56.4) | 1.32 ± 1.46 | 15136 (66.0) | 1.0 ± 1.33 | 19916 (86.9) |

| Mild | 6306 (27.5) | 6.93 ± 1.45 | 5283 (23.0) | 6.63 ± 1.18 | - |

| Moderate | 2288 (10.0) | 11.59 ± 1.39 | 1646 (7.2) | 11.84 ± 1.44 | - |

| Moderately severe | 923 (4.0) | 16.67 ± 1.41 | - | - | - |

| Severe | 467 (2.0) | 22.94 ± 2.39 | 860 (3.8) | 17.89 ± 2.22 | - |

| Overall prevalence | 3678 (16.0) | - | 5515 (24.1) | - | 3009 (13.1) |

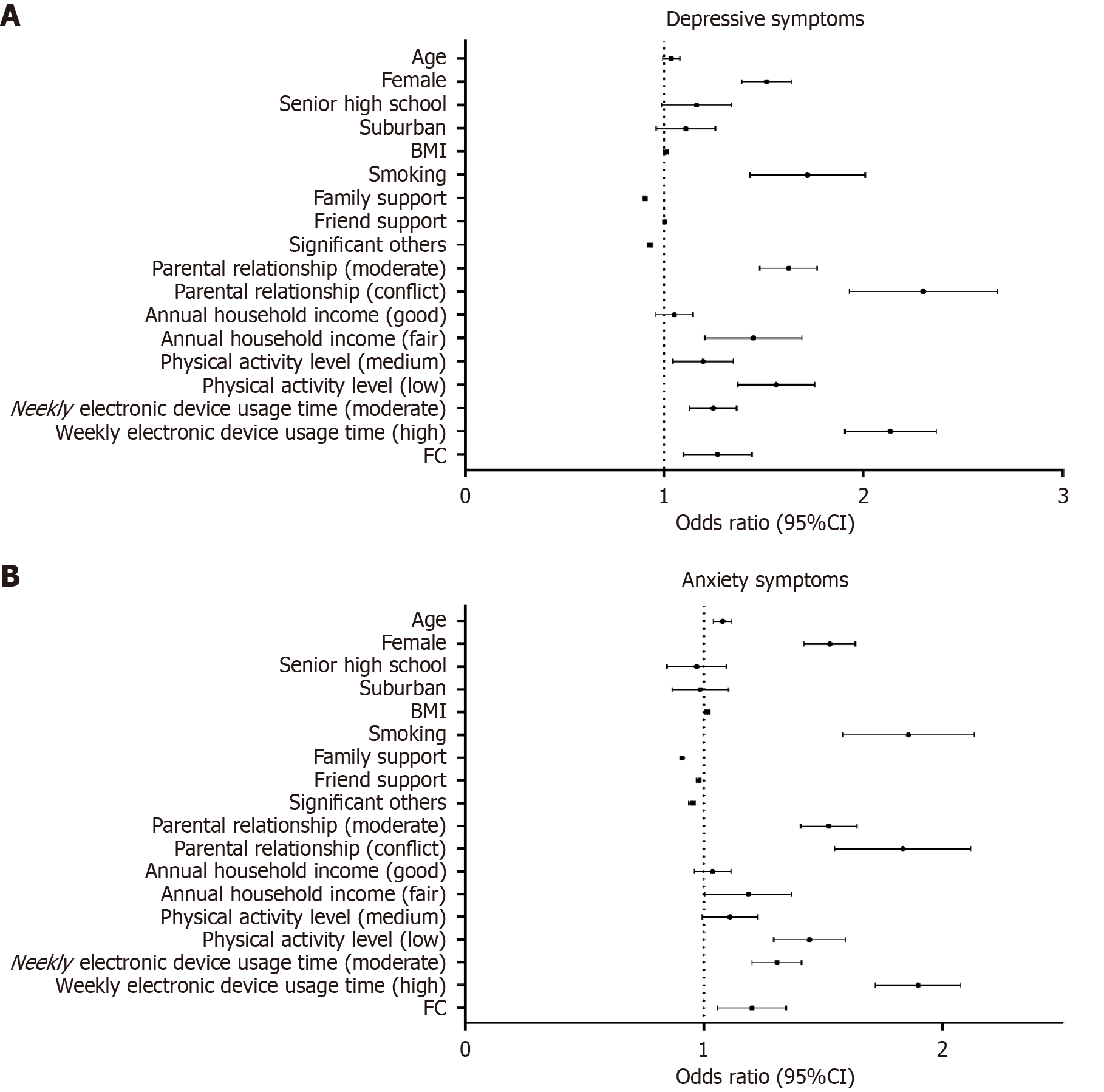

Binary logistic regression analyses (Table 3) identified female sex [B = 0.413, P < 0.001, odds ratio (OR) = 1.511, 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.391-1.641], smoking (B = 0.533, P < 0.001, OR = 1.704, 95%CI: 1.440-2.017), and FC (B = 0.232, P = 0.001, OR = 1.261, 95%CI: 1.101-1.444) as significant risk factors for depressive symptoms in adolescents. A parental relationship characterized as “moderate” (B = 0.482, P < 0.001, OR = 1.619, 95%CI: 1.482-1.770) or by “conflict” (B = 0.825, P < 0.001, OR = 2.282, 95%CI: 1.940-2.684) was also a significant risk factor for depressive symptoms compared to a relationship characterized by “harmony”. In addition, a physical activity level rated as “moderate” (B = 0.173, P = 0.008, OR = 1.188, 95%CI: 1.047-1.349) or “low” (B = 0.441, P < 0.001, OR = 1.555, 95%CI: 1.373-1.760), a WEDUT level rated “moderate” (B = 0.217, P < 0.001, OR = 1.243, 95%CI: 1.131-1.366) or “high” (B = 0.756, P < 0.001, OR = 2.129, 95%CI: 1.912-2.370), and a “fair” annual household income (B = 0.360, P < 0.001, OR = 1.434, 95%CI: 1.211-1.698) were risk factors for depressive symptoms. As expected, family support (B = -0.101, P < 0.001, OR = 0.904, 95%CI: 0.894-0.914) and the support of significant others (B = -0.075, P < 0.001, OR = 0.928, 95%CI: 0.915-0.941) were associated with reduced risk of depressive symptoms. Conversely, age, educational level, region of residence, BMI, and friend support were not significantly associated with depressive symptoms (all P > 0.05).

| Characteristic | Depressive symptoms | Anxiety symptoms | ||||

| OR | 95%CI | P value | OR | 95%CI | P value | |

| Age | 1.034 | 0.992-1.079 | 0.116 | 1.078 | 1.040-1.117 | < 0.001 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| Female | 1.511 | 1.391-1.641 | < 0.001 | 1.525 | 1.421-1.636 | < 0.001 |

| Educational level | ||||||

| Junior high school | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| Senior high school | 1.154 | 0.993-1.342 | 0.062 | 0.965 | 0.848-1.097 | 0.586 |

| Regions | ||||||

| Urban | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| Suburban | 1.102 | 0.963-1.261 | 0.159 | 0.981 | 0.869-1.106 | 0.751 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 1.010 | 0.999-1.021 | 0.062 | 1.016 | 1.007-1.026 | < 0.001 |

| Smoking | ||||||

| No | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| Yes | 1.704 | 1.440-2.017 | < 0.001 | 1.843 | 1.589-2.138 | < 0.001 |

| PSSS | ||||||

| Family support | 0.904 | 0.894-0.914 | < 0.001 | 0.908 | 0.899-0.917 | < 0.001 |

| Friend support | 0.999 | 0.988-1.010 | 0.864 | 0.978 | 0.968-0.987 | < 0.001 |

| Significant others | 0.928 | 0.915-0.941 | < 0.001 | 0.949 | 0.937-0.962 | < 0.001 |

| Parental relationship | ||||||

| Harmony | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| Moderate | 1.619 | 1.482-1.770 | < 0.001 | 1.521 | 1.407-1.643 | < 0.001 |

| Conflict | 2.282 | 1.940-2.682 | < 0.001 | 1.818 | 1.556-2.124 | < 0.001 |

| Annual household income | ||||||

| Better | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| Good | 1.048 | 0.959-1.146 | 0.303 | 1.035 | 0.961-1.115 | 0.366 |

| Fair | 1.434 | 1.211-1.698 | < 0.001 | 1.177 | 1.010-1.372 | 0.037 |

| Physical activity level | ||||||

| High | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| Medium | 1.188 | 1.047-1.349 | 0.008 | 1.106 | 0.996-1.229 | 0.060 |

| Low | 1.555 | 1.373-1.760 | < 0.001 | 1.437 | 1.296-1.594 | < 0.001 |

| WEDUT | ||||||

| Low | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| Moderate | 1.243 | 1.131-1.366 | < 0.001 | 1.303 | 1.204-1.411 | < 0.001 |

| High | 2.129 | 1.912-2.370 | < 0.001 | 1.891 | 1.720-2.078 | < 0.001 |

| FC | ||||||

| No | 1 | - | - | 1 | - | - |

| Yes | 1.261 | 1.101-1.444 | 0.001 | 1.195 | 1.060-1.348 | 0.004 |

Age (B = 0.075, P < 0.001, OR = 1.078, 95%CI: 1.040-1.117), female sex (B = 0.422, P < 0.001, OR = 1.525, 95%CI: 1.421-1.636), high BMI (B = 0.016, P < 0.001, OR = 1.016, 95%CI: 1.007-1.026), smoking (B = 0.611, P < 0.001, OR = 1.843, 95%CI: 1.589-2.138), and FC (B = 0.178, P = 0.004, OR = 1.195, 95%CI: 1.060-1.348) were significant independent factors for anxiety symptoms. In addition, a parental relationship characterized as “moderate” (B = 0.419, P < 0.001, OR = 1.521, 95%CI: 1.407-1.643) or by “conflict” (B = 0.598, P < 0.001, OR = 1.818, 95%CI: 1.556-2.124) was a risk factor compared to a parental relationship characterized by “harmony”. A “fair” annual household income (B = 0.163, P = 0.037, OR = 1.177, 95%CI: 1.010-1.372), low physical activity level (B = 0.363, P < 0.001, OR = 1.437, 95%CI: 1.296-1.594), and low WEDUT (B = 0.637, P < 0.001, OR = 1.891, 95%CI: 1.720-2.078) were also risk factors for adolescent anxiety symptoms. Conversely, family support (B = -0.096, P < 0.001, OR = 0.908, 95%CI: 0.899-0.917), friend support (B = -0.023, P < 0.001, OR = 0.978, 95%CI: 0.968-0.987), and support from significant others (B = -0.052, P < 0.001, OR = 0.949, 95%CI: 0.937-0.962) were associated lower risk of adolescent anxiety symptoms. Level of education and region of residence were not significantly associated with adolescent anxiety (all P > 0.05). As shown in Figure 2.

This study yielded several key findings. First, substantial minorities of the sampled adolescent cohort reported depressive (16.0%) and anxiety (24.1%) symptoms, with 13.1% experiencing both. Second, over 10% of the total cohort rated these psychiatric symptoms as moderate to severe. Third, FC, lower levels of physical activity, and longer durations of WEDUT were identified as risk factors for both depression and anxiety, while perceived support emerged as an important protective factor.

Whilst numerous studies have investigated the prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms among adolescents in the general population, results have varied across samples, suggesting influences by multiple uncontrolled or unknown risk and protective factors as well as differences in research methodologies (e.g., sample selection, symptom criteria, population ethnicity, etc.)[23,52]. Nonetheless, the prevalence of both symptom types is high. For instance, a network perspective reported depressive symptoms in 44.6% and anxiety symptoms in 31.12% of adolescents aged 12-20 years in Chinese[53]. Further, symptom expression is strongly predictive of future clinical depression, as an overview of 113 studies reported that the subgroup with subthreshold symptoms (14.17% of the adolescents sampled) was at 2.95-fold greater risk of developing depression than the non-depressed subgroup[54]. Another summary and overview reported a lifetime anxiety disorder prevalence of 15%-20% up to age 18 years[55]. Thus, despite considerable heterogeneity across populations, preclinical depressive and anxiety symptoms are ubiquitous among adolescents and contribute not only to reduced quality of life, lower achievement, and potential harm in the short term but also to poor mental health in adulthood.

Our findings regarding depressive and anxiety symptoms in adolescents may reflect the complex nature of adolescent psychological development and the potentially transient nature of developmental and emotional distress[56,57]. Nonetheless, adequate attention and intervention are required to minimize progression. This trend also suggests that severe psychological problems require more complex triggering mechanisms and longer developmental processes[58]. Of greater concern is the small group (about 10%) reporting moderate to severe symptoms, as these are often associated with higher levels of functional impairment and decreased future quality of life[59-61]. Thus, without timely intervention, these symptoms may have a profound impact on life outcomes[62,63].

We also identified multiple risk factors for these depressive and anxiety symptoms, although most are likely not independent but rather mutually influence symptom development and expression within a complex causal network[64-66]. The risk conferred by female sex may be attributed to hormonal changes during puberty or to stress-related cytokines[67,68]. We also detected a significant association between time spent using electronic devices (such as internet surfing) and symptoms of depression and anxiety, in accord with previous studies[69-71]. It is possible that prolonged WEDUT interferes with academics and limits physical activity, leading to deleterious effects on health and self-image. Alternatively, excessive WEDUT may be a coping mechanism. Adolescents in families with lower incomes were also at greater risk for depressive and anxiety symptoms, potentially due to higher levels of financial stress[72], while lower levels of physical activity enhanced risk due to declines in physical health, self-esteem, and other sequelae[73]. Academic and social pressures as well as self-expectations increase with age and may cause anxiety symptoms[38], while excess weight may trigger concerns about body image[74]. Support received by adolescents was an important protective factor against symptoms of depression and anxiety, consistent with the findings of previous studies[75,76]. A longitudinal study also reported that poor family functioning promoted depression, anxiety, and aggression in adolescents[77].

The current study further supports the associations of depressive and anxiety symptoms with FC, particularly in Chinese adolescents. A previous systematic review and meta-analysis reported a pooled global FC prevalence of 15.3%[51]. However, prevalence varies markedly by region, with lower estimates of 8.5% in China[78], 8.1% in Thailand[79], and 6.8% in Germany[80], but 27% in Nigeria[81] and 12.6% in Mexico[82]. Further, FC is more common among adolescents, and may impact daily life and learning. Notably, the risk of FC was 1.261 times higher in adolescents with depressive symptoms compared to those without, and 1.195 times higher in adolescents with anxiety symptoms compared to those without. The potential mechanisms underlying these associations remain unclear. As a cross-sectional study, we cannot determine the direction of causality, and a bidirectional relationship may exist between depressive and anxiety symptoms and persistent bowel dysfunction. The literature suggests that associations of psychological symptoms such as depression and anxiety with FC may be mediated by brain-gut axis dysfunction[83], the stress response[84], abnormalities in gut microbiome composition (dysbiosis)[85], deleterious lifestyle factors (poor diet)[86,87], and altered neurotransmitters[88]. These interactions warrant further research.

These results have significant implications for clinical practice and policy making. First, the relatively high prevalence of depressive and anxiety symptoms among adolescents and the documented associations of these symptoms with adult mental illness indicate the need for general screening to facilitate timely and effective intervention as well as enhanced provision of mental health and medical resources. Second, individually tailored and staged intervention strategies should be implemented according to symptom severity. For instance, early detection and intervention at the level of the school could prevent further aggravation of mild symptoms, while severe symptoms should ideally be addressed by professional counseling and pharmacological therapies. Increased attention, understanding, and support from parents, schools, and communities could facilitate the development and implementation of systematic mental health education and intervention schemes within schools, homes, and communities.

This study has several limitations. First, the cross-sectional design does not allow for demonstration of causal rela

In conclusion, depressive and anxiety symptoms, including moderate to severe symptoms, are prevalent among adolescents, and are influenced by numerous factors such gender, smoking, home environment, physical activity, age, and BMI. In addition, we demonstrate significant associations with FC. These findings emphasize the importance of providing adolescents with comprehensive mental health support, including guidance on coping strategies, positive lifestyle choices, and maintaining a favorable environment in order to prevent and mitigate depressive and anxiety symptoms. A deeper comprehension of adolescent mental health issues, coupled with reinforced multidimensional and multilevel comprehensive interventions, is key to effectively improving mental health standards among adolescents.

We would like to thank the participants in the study.

| 1. | COVID-19 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global prevalence and burden of depressive and anxiety disorders in 204 countries and territories in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2021;398:1700-1712. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2518] [Cited by in RCA: 3080] [Article Influence: 616.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Manfro PH, Pereira RB, Rosa M, Cogo-Moreira H, Fisher HL, Kohrt BA, Mondelli V, Kieling C. Adolescent depression beyond DSM definition: a network analysis. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2023;32:881-892. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 8.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Alaie I, Ssegonja R, Philipson A, von Knorring AL, Möller M, von Knorring L, Ramklint M, Bohman H, Feldman I, Hagberg L, Jonsson U. Adolescent depression, early psychiatric comorbidities, and adulthood welfare burden: a 25-year longitudinal cohort study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2021;56:1993-2004. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Piao J, Huang Y, Han C, Li Y, Xu Y, Liu Y, He X. Alarming changes in the global burden of mental disorders in children and adolescents from 1990 to 2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2022;31:1827-1845. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 35.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Cooper R, Di Biase MA, Bei B, Allen NB, Schwartz O, Whittle S, Cropley V. Development of morning-eveningness in adolescence: implications for brain development and psychopathology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2023;64:449-460. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 3.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020;396:1204-1222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13226] [Cited by in RCA: 12033] [Article Influence: 2005.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (41)] |

| 7. | GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of 12 mental disorders in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet Psychiatry. 2022;9:137-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 436] [Cited by in RCA: 3516] [Article Influence: 879.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Lu J, Xu X, Huang Y, Li T, Ma C, Xu G, Yin H, Xu X, Ma Y, Wang L, Huang Z, Yan Y, Wang B, Xiao S, Zhou L, Li L, Zhang Y, Chen H, Zhang T, Yan J, Ding H, Yu Y, Kou C, Shen Z, Jiang L, Wang Z, Sun X, Xu Y, He Y, Guo W, Jiang L, Li S, Pan W, Wu Y, Li G, Jia F, Shi J, Shen Z, Zhang N. Prevalence of depressive disorders and treatment in China: a cross-sectional epidemiological study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8:981-990. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 477] [Cited by in RCA: 529] [Article Influence: 105.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Wang S, Li Q, Lu J, Ran H, Che Y, Fang D, Liang X, Sun H, Chen L, Peng J, Shi Y, Xiao Y. Treatment Rates for Mental Disorders Among Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6:e2338174. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Faisal-Cury A, Ziebold C, Rodrigues DMO, Matijasevich A. Depression underdiagnosis: Prevalence and associated factors. A population-based study. J Psychiatr Res. 2022;151:157-165. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 52] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | World Health Organization. World Mental Health Report: transforming mental health for all. Jun 16, 2022. [cited 11 August 2025]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240049338. |

| 12. | Racine N, McArthur BA, Cooke JE, Eirich R, Zhu J, Madigan S. Global Prevalence of Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms in Children and Adolescents During COVID-19: A Meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175:1142-1150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1353] [Cited by in RCA: 1530] [Article Influence: 306.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Kasturi S, Oguoma VM, Grant JB, Niyonsenga T, Mohanty I. Prevalence Rates of Depression and Anxiety among Young Rural and Urban Australians: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20:800. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 32] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 9.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Shorey S, Ng ED, Wong CHJ. Global prevalence of depression and elevated depressive symptoms among adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Psychol. 2022;61:287-305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 791] [Article Influence: 158.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Jang H, Son H, Kim J. Classmates' Discrimination Experiences and Adolescent Depressive Symptoms: Evidence From Random Assignment of Students to Classrooms in South Korea. J Adolesc Health. 2023;72:914-922. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Xu C, Wang S, Su BB, Ozuna K, Mao C, Dai Z, Wang K. Associations of adolescent substance use and depressive symptoms with adult major depressive disorder in the United States: NSDUH 2016-2019. J Affect Disord. 2024;344:397-406. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Andersson P, Jokinen J, Jarbin H, Lundberg J, Desai Boström AE. Association of Bipolar Disorder Diagnosis With Suicide Mortality Rates in Adolescents in Sweden. JAMA Psychiatry. 2023;80:796-802. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Liang Y, Chen J, Xiong Y, Wang Q, Ren P. Profiles and Transitions of Non-Suicidal Self-Injury and Depressive Symptoms among Adolescent Boys and Girls: Predictive Role of Bullying Victimization. J Youth Adolesc. 2023;52:1705-1720. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Lee CS, Sin EJ, Park M, Okazaki S, Choi Y. Cultural family processes, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation: A longitudinal study of Asian American youths. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2023;53:802-817. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Shrestha S, Phuyal R, Chalise P. Depression, Anxiety and Stress among School-going Adolescents of a Secondary School: A Descriptive Cross-sectional Study. JNMA J Nepal Med Assoc. 2023;61:249-251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Dien TM, Chi PTL, Duy PQ, Anh LH, Ngan NTK, Hoang Lan VT. Prevalence of internet addiction and anxiety, and factors associated with the high level of anxiety among adolescents in Hanoi, Vietnam during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Public Health. 2023;23:2441. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Essayagh F, Essayagh M, Essayagh S, Marc I, Bukassa G, El Otmani I, Kouyate MF, Essayagh T. The prevalence and risk factors for anxiety and depression symptoms among migrants in Morocco. Sci Rep. 2023;13:3740. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Piscoya-Tenorio JL, Heredia-Rioja WV, Morocho-Alburqueque N, Zeña-Ñañez S, Hernández-Yépez PJ, Díaz-Vélez C, Failoc-Rojas VE, Valladares-Garrido MJ. Prevalence and Factors Associated with Anxiety and Depression in Peruvian Medical Students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2023;20:2907. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 2.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein M, Swanson SA, Avenevoli S, Cui L, Benjet C, Georgiades K, Swendsen J. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication--Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49:980-989. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4651] [Cited by in RCA: 3766] [Article Influence: 235.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Gallagher C, Pirkis J, Lambert KA, Perret JL, Ali GB, Lodge CJ, Bowatte G, Hamilton GS, Matheson MC, Bui DS, Abramson MJ, Walters EH, Dharmage SC, Erbas B. Life course BMI trajectories from childhood to mid-adulthood are differentially associated with anxiety and depression outcomes in middle age. Int J Obes (Lond). 2023;47:661-668. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Busby Grant J, Batterham PJ, McCallum SM, Werner-Seidler A, Calear AL. Specific anxiety and depression symptoms are risk factors for the onset of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in youth. J Affect Disord. 2023;327:299-305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Wang M, Mou X, Li T, Zhang Y, Xie Y, Tao S, Wan Y, Tao F, Wu X. Association Between Comorbid Anxiety and Depression and Health Risk Behaviors Among Chinese Adolescents: Cross-Sectional Questionnaire Study. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2023;9:e46289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Zajkowska Z, Walsh A, Zonca V, Gullett N, Pedersen GA, Kieling C, Swartz JR, Karmacharya R, Fisher HL, Kohrt BA, Mondelli V. A systematic review of the association between biological markers and environmental stress risk factors for adolescent depression. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;138:163-175. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 40] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 9.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Caserini C, Ferro M, Nobile M, Scaini S, Michelini G. Shared genetic influences between depression and conduct disorder in children and adolescents: A systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2023;322:31-38. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Zwolińska W, Dmitrzak-Węglarz M, Słopień A. Biomarkers in Child and Adolescent Depression. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2023;54:266-281. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Lee JY, Patel M, Scior K. Self-esteem and its relationship with depression and anxiety in adults with intellectual disabilities: a systematic literature review. J Intellect Disabil Res. 2023;67:499-518. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 3.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Vucenovic D, Sipek G, Jelic K. The Role of Emotional Skills (Competence) and Coping Strategies in Adolescent Depression. Eur J Investig Health Psychol Educ. 2023;13:540-552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Moulds ML, Bisby MA, Black MJ, Jones K, Harrison V, Hirsch CR, Newby JM. Repetitive negative thinking in the perinatal period and its relationship with anxiety and depression. J Affect Disord. 2022;311:446-462. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Kidd KN, Prasad D, Cunningham JEA, de Azevedo Cardoso T, Frey BN. The relationship between parental bonding and mood, anxiety and related disorders in adulthood: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2022;307:221-236. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Yang J, Kim M, Wang J, Zhang Y, Schoppe-Sullivan SJ, Yoon S. Coparenting, parental anxiety/depression, and child behavior problems: The actor-partner interdependence model with low-income married couples. J Fam Psychol. 2023;37:1230-1240. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Nakama N, Usui N, Doi M, Shimada S. Early life stress impairs brain and mental development during childhood increasing the risk of developing psychiatric disorders. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2023;126:110783. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Potter JR, Yoon KL. Interpersonal Factors, Peer Relationship Stressors, and Gender Differences in Adolescent Depression. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2023;25:759-767. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Steare T, Gutiérrez Muñoz C, Sullivan A, Lewis G. The association between academic pressure and adolescent mental health problems: A systematic review. J Affect Disord. 2023;339:302-317. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 120] [Cited by in RCA: 125] [Article Influence: 41.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Ye XL, Zhang W, Zhao FF. Depression and internet addiction among adolescents:A meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2023;326:115311. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Adibi P, Abdoli M, Daghaghzadeh H, Keshteli AH, Afshar H, Roohafza H, Esmaillzadeh A, Feizi A. Relationship between Depression and Constipation: Results from a Large Cross-sectional Study in Adults. Korean J Gastroenterol. 2022;80:77-84. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Gupta S, Dinesh S, Sharma S. Bridging the Mind and Gut: Uncovering the Intricacies of Neurotransmitters, Neuropeptides, and their Influence on Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Cent Nerv Syst Agents Med Chem. 2024;24:2-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Wu WL, Adame MD, Liou CW, Barlow JT, Lai TT, Sharon G, Schretter CE, Needham BD, Wang MI, Tang W, Ousey J, Lin YY, Yao TH, Abdel-Haq R, Beadle K, Gradinaru V, Ismagilov RF, Mazmanian SK. Microbiota regulate social behaviour via stress response neurons in the brain. Nature. 2021;595:409-414. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 229] [Article Influence: 45.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Seaman EL, Chandora R. The Importance of Global Youth E-Cigarette Use Surveillance: Opportunities and Next Steps. Am J Public Health. 2022;112:541-543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16:606-613. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21545] [Cited by in RCA: 31268] [Article Influence: 1250.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Wang W, Bian Q, Zhao Y, Li X, Wang W, Du J, Zhang G, Zhou Q, Zhao M. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) in the general population. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36:539-544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 481] [Cited by in RCA: 983] [Article Influence: 81.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Zhou Y, Shi H, Liu Z, Peng S, Wang R, Qi L, Li Z, Yang J, Ren Y, Song X, Zeng L, Qian W, Zhang X. The prevalence of psychiatric symptoms of pregnant and non-pregnant women during the COVID-19 epidemic. Transl Psychiatry. 2020;10:319. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 78] [Cited by in RCA: 72] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Jiang BC, Zhang J, Yang M, Yang HD, Zhang XB. Prevalence and risk factors of depressive and anxiety symptoms and functional constipation among university students in Eastern China. World J Psychiatry. 2025;15:106451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 48. | Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, Löwe B. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1092-1097. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11947] [Cited by in RCA: 20762] [Article Influence: 1038.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Sun J, Liang K, Chi X, Chen S. Psychometric Properties of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale-7 Item (GAD-7) in a Large Sample of Chinese Adolescents. Healthcare (Basel). 2021;9:1709. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 165] [Article Influence: 33.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Tong X, An D, McGonigal A, Park SP, Zhou D. Validation of the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) among Chinese people with epilepsy. Epilepsy Res. 2016;120:31-36. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 230] [Cited by in RCA: 361] [Article Influence: 32.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Barberio B, Judge C, Savarino EV, Ford AC. Global prevalence of functional constipation according to the Rome criteria: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;6:638-648. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 203] [Cited by in RCA: 254] [Article Influence: 50.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (2)] |

| 52. | Bajraktarov S, Kunovski I, Raleva M, Bolinski F, Isjanovska R, Kalpak G, Novotni A, Hadzihamza K, Stefanovski B. Depression and Anxiety in Adolescents and their Caregivers: A Cross-Sectional Study from North Macedonia. Pril (Makedon Akad Nauk Umet Odd Med Nauki). 2023;44:47-56. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Cai H, Chow IHI, Lei SM, Lok GKI, Su Z, Cheung T, Peshkovskaya A, Tang YL, Jackson T, Ungvari GS, Zhang L, Xiang YT. Inter-relationships of depressive and anxiety symptoms with suicidality among adolescents: A network perspective. J Affect Disord. 2023;324:480-488. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Zhang R, Peng X, Song X, Long J, Wang C, Zhang C, Huang R, Lee TMC. The prevalence and risk of developing major depression among individuals with subthreshold depression in the general population. Psychol Med. 2023;53:3611-3620. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 94] [Article Influence: 31.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Rapee RM, Creswell C, Kendall PC, Pine DS, Waters AM. Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents: A summary and overview of the literature. Behav Res Ther. 2023;168:104376. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 61] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | McGuinty J, Carlson A, Li A, Nelson J. A novel walk-in clinic treatment intervention for youth presenting with anxiety and depression. J Child Adolesc Psychiatr Nurs. 2022;35:104-112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Eiland L, Romeo RD. Stress and the developing adolescent brain. Neuroscience. 2013;249:162-171. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 275] [Cited by in RCA: 324] [Article Influence: 23.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 58. | McGrath JJ, Al-Hamzawi A, Alonso J, Altwaijri Y, Andrade LH, Bromet EJ, Bruffaerts R, de Almeida JMC, Chardoul S, Chiu WT, Degenhardt L, Demler OV, Ferry F, Gureje O, Haro JM, Karam EG, Karam G, Khaled SM, Kovess-Masfety V, Magno M, Medina-Mora ME, Moskalewicz J, Navarro-Mateu F, Nishi D, Plana-Ripoll O, Posada-Villa J, Rapsey C, Sampson NA, Stagnaro JC, Stein DJ, Ten Have M, Torres Y, Vladescu C, Woodruff PW, Zarkov Z, Kessler RC; WHO World Mental Health Survey Collaborators. Age of onset and cumulative risk of mental disorders: a cross-national analysis of population surveys from 29 countries. Lancet Psychiatry. 2023;10:668-681. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 105] [Cited by in RCA: 298] [Article Influence: 99.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Gili M, García Toro M, Armengol S, García-Campayo J, Castro A, Roca M. Functional impairment in patients with major depressive disorder and comorbid anxiety disorder. Can J Psychiatry. 2013;58:679-686. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Aderka IM, Hofmann SG, Nickerson A, Hermesh H, Gilboa-Schechtman E, Marom S. Functional impairment in social anxiety disorder. J Anxiety Disord. 2012;26:393-400. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 158] [Cited by in RCA: 203] [Article Influence: 14.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Sherif Y, Azman AZF, Awang H, Mokhtar SA, Mohammadzadeh M, Alimuddin AS. Effectiveness of Life Skills Intervention on Depression, Anxiety and Stress among Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Malays J Med Sci. 2023;30:42-59. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Ayvaci ER, Croarkin PE. Special Populations: Treatment-Resistant Depression in Children and Adolescents. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2023;46:359-370. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Kunas SL, Lautenbacher LM, Lueken PU, Hilbert K. Psychological Predictors of Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Outcomes for Anxiety and Depressive Disorders in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Affect Disord. 2021;278:614-626. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 37] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | McEvoy D, Brannigan R, Cooke L, Butler E, Walsh C, Arensman E, Clarke M. Risk and protective factors for self-harm in adolescents and young adults: An umbrella review of systematic reviews. J Psychiatr Res. 2023;168:353-380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 60] [Article Influence: 20.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Yang T, Guo Z, Zhu X, Liu X, Guo Y. The interplay of personality traits, anxiety, and depression in Chinese college students: a network analysis. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1204285. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Lo Buglio G, Pontillo M, Cerasti E, Polari A, Schiano Lomoriello A, Vicari S, Lingiardi V, Boldrini T, Solmi M. A network analysis of anxiety, depressive, and psychotic symptoms and functioning in children and adolescents at clinical high risk for psychosis. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:1016154. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Zajkowska Z, Nikkheslat N, Manfro PH, Souza L, Rohrsetzer F, Viduani A, Pereira R, Piccin J, Zonca V, Walsh AEL, Gullett N, Fisher HL, Swartz JR, Kohrt BA, Kieling C, Mondelli V. Sex-specific inflammatory markers of risk and presence of depression in adolescents. J Affect Disord. 2023;342:69-75. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Hu S, Li X, Yang L. Effects of physical activity in child and adolescent depression and anxiety: role of inflammatory cytokines and stress-related peptide hormones. Front Neurosci. 2023;17:1234409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Mougharbel F, Chaput JP, Sampasa-Kanyinga H, Colman I, Leatherdale ST, Patte KA, Goldfield GS. Longitudinal associations between different types of screen use and depression and anxiety symptoms in adolescents. Front Public Health. 2023;11:1101594. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Tran HGN, Thai TT, Dang NTT, Vo DK, Duong MHT. Cyber-Victimization and Its Effect on Depression in Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2023;24:1124-1139. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 47] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Goh WS, Tan JHN, Luo Y, Ng SH, Sulaiman MSBM, Wong JCM, Loh VWK. Risk and protective factors associated with adolescent depression in Singapore: a systematic review. Singapore Med J. 2025;66:2-14. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | de Castro F, Cappa C, Madans J. Anxiety and Depression Signs Among Adolescents in 26 Low- and Middle-Income Countries: Prevalence and Association With Functional Difficulties. J Adolesc Health. 2023;72:S79-S87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Recchia F, Bernal JDK, Fong DY, Wong SHS, Chung PK, Chan DKC, Capio CM, Yu CCW, Wong SWS, Sit CHP, Chen YJ, Thompson WR, Siu PM. Physical Activity Interventions to Alleviate Depressive Symptoms in Children and Adolescents: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatr. 2023;177:132-140. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 30] [Cited by in RCA: 98] [Article Influence: 32.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Gallagher C, Waidyatillake N, Pirkis J, Lambert K, Cassim R, Dharmage S, Erbas B. The effects of weight change from childhood to adulthood on depression and anxiety risk in adulthood: A systematic review. Obes Rev. 2023;24:e13566. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Scardera S, Perret LC, Ouellet-Morin I, Gariépy G, Juster RP, Boivin M, Turecki G, Tremblay RE, Côté S, Geoffroy MC. Association of Social Support During Adolescence With Depression, Anxiety, and Suicidal Ideation in Young Adults. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2027491. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 79] [Cited by in RCA: 137] [Article Influence: 22.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Peñate W, González-Loyola M, Oyanadel C. The Predictive Role of Affectivity, Self-Esteem and Social Support in Depression and Anxiety in Children and Adolescents. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17:6984. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Zhang C, Zhang Q, Zhuang H, Xu W. The reciprocal relationship between depression, social anxiety and aggression in Chinese adolescents: The moderating effects of family functioning. J Affect Disord. 2023;329:379-384. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 25] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Chen Z, Peng Y, Shi Q, Chen Y, Cao L, Jia J, Liu C, Zhang J. Prevalence and Risk Factors of Functional Constipation According to the Rome Criteria in China: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Med (Lausanne). 2022;9:815156. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 7.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Siajunboriboon S, Tanpowpong P, Empremsilapa S, Lertudomphonwanit C, Nuntnarumit P, Treepongkaruna S. Prevalence of functional abdominal pain disorders and functional constipation in adolescents. J Paediatr Child Health. 2022;58:1209-1214. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Classen M, Righini-Grunder F, Schumann S, Gontard AV, Laffolie J. Constipation in Children and Adolescents. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2022;119:697-708. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Udoh EE, Rajindrajith S, Devanarayana NM, Benninga MA. Prevalence and risk factors for functional constipation in adolescent Nigerians. Arch Dis Child. 2017;102:841-844. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Dhroove G, Saps M, Garcia-Bueno C, Leyva Jiménez A, Rodriguez-Reynosa LL, Velasco-Benítez CA. Prevalence of functional gastrointestinal disorders in Mexican schoolchildren. Rev Gastroenterol Mex. 2017;82:13-18. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 2.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Foster JA, McVey Neufeld KA. Gut-brain axis: how the microbiome influences anxiety and depression. Trends Neurosci. 2013;36:305-312. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1299] [Cited by in RCA: 1598] [Article Influence: 122.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Bear T, Dalziel J, Coad J, Roy N, Butts C, Gopal P. The Microbiome-Gut-Brain Axis and Resilience to Developing Anxiety or Depression under Stress. Microorganisms. 2021;9:723. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 85] [Article Influence: 17.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Simpson CA, Diaz-Arteche C, Eliby D, Schwartz OS, Simmons JG, Cowan CSM. The gut microbiota in anxiety and depression - A systematic review. Clin Psychol Rev. 2021;83:101943. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 599] [Cited by in RCA: 613] [Article Influence: 122.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Chuah KH, Mahadeva S. Cultural Factors Influencing Functional Gastrointestinal Disorders in the East. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2018;24:536-543. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 41] [Cited by in RCA: 49] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Vriesman MH, Koppen IJN, Camilleri M, Di Lorenzo C, Benninga MA. Management of functional constipation in children and adults. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;17:21-39. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 297] [Article Influence: 49.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Pan R, Wang L, Xu X, Chen Y, Wang H, Wang G, Zhao J, Chen W. Crosstalk between the Gut Microbiome and Colonic Motility in Chronic Constipation: Potential Mechanisms and Microbiota Modulation. Nutrients. 2022;14:3704. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 96] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/