Published online Feb 19, 2026. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v16.i2.113037

Revised: October 9, 2025

Accepted: November 6, 2025

Published online: February 19, 2026

Processing time: 170 Days and 5.4 Hours

As the role of non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) in psychiatric disorders gains increa

Core Tip: Non-coding RNAs encapsulated within extracellular vesicles, particularly exosomes, play a crucial role in the pathophysiology of psychiatric disorders and are involved in key processes such as neurogenesis, synaptic plasticity, and neuronal stress responses, making them promising biomarkers for diagnosing and treating psychiatric conditions. Their stability and disease-specific expression further enhance their potential in advancing psychiatric research and therapeutic strategies.

- Citation: Cao Y, Li PF, Zhu L, Li K, He KJ. Non-coding RNA in extracellular vesicles and the occurrence and progression of psychiatric disorders: A narrative review. World J Psychiatry 2026; 16(2): 113037

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v16/i2/113037.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v16.i2.113037

Psychiatric disorders, also known as mental disorders or mental illnesses, represent a diverse group of conditions that affect an individual’s cognitive, emotional, and behavioral functioning. Psychiatric disorders affect millions worldwide, including over 6.4 million individuals diagnosed with schizophrenia (SCZ), approximately 1.1 million suffering from bipolar disorder (BD)[1,2], and an alarming 193 million cases of major depressive disorder (MDD)[3]. Despite the clinical differences, all three disorders have neurodevelopmental origins, and studies have shown overlapping relationships and commonalities in underlying biological mechanisms[4].

Currently, physicians have a misdiagnosis rate of up to one-quarter during clinical diagnosis based on epidemiologic studies, as well as subjective feelings and expressions of patients that tend to influence clinicians’ assessment, and a high degree of heterogeneity in patients’ responses to antipsychotic medications, which are clinical problems that lead to delays or inappropriate management during the treatment of psychiatric disorders. Therefore, there is an urgent need for a reliable and objective biomarker to help clinicians achieve accurate diagnoses and treatments. In addition, a significant number of psychiatric patients do not respond well to commercially available medications. The primary reason is the incomplete understanding of the underlying mechanisms of these disorders and the limited biologically based guidance available for clinicians. This shortage of guidance hinders their ability to predict the progression of psychiatric disorders in high-risk patients and prescribe drugs that can effectively treat them.

Non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs), including microRNAs (miRNAs), circular RNAs (circRNAs), and long ncRNAs (lnc

NcRNAs are not only critical regulators of cellular processes but are also actively packaged into extracellular vesicles (EVs), where they mediate intercellular communication. EVs, including exosomes, are membrane-bound nanoparticles secreted by cells that carry bioactive molecules such as RNAs, proteins, and lipids. These vesicles serve as critical mediators of intercellular communication, facilitating the transfer of molecular cargo between cells and influencing processes such as immune modulation, synaptic plasticity, and neuronal survival[10]. EVs are readily detectable in accessible body fluids, including blood, urine, and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), making them an attractive tool for liquid biopsy. Liquid biopsy is a non-invasive technique that analyzes biomarkers such as circulating tumor DNA, circulating tumor cells, or exosomes in bodily fluids like blood to detect cancer and other diseases[11]. NcRNAs encapsulated within EVs not only enhance the stability and bioavailability of ncRNAs but also allow them to exert systemic effects across different tissues and organs. Moreover, the ability to profile EV-derived ncRNAs from peripheral blood provides a mini

Recent studies have demonstrated the potential of EV-associated ncRNAs in unraveling the molecular mechanisms underlying psychiatric disorders[12]. For instance, specific miRNAs and lncRNAs carried by EVs have been implicated in the dysregulation of neuroinflammatory pathways, synaptic dysfunction, and neurotransmitter imbalances observed in these conditions[12]. This emerging field not only provides novel insights into the pathogenesis of psychiatric disorders but also opens new avenues for developing targeted therapies. This review aims to comprehensively summarize the relationships between ncRNAs in EVs and major psychiatric disorders, as well as the current state of research in this field. Based on these findings, this review endeavors to provide insights and novel perspectives for the discovery of new diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets for psychiatric disorders.

SCZ is a chronic psychiatric disorder characterized by abnormalities in perception, emotion, and behavior. It has a lifetime prevalence of around 1%, onset typically occurs during adolescence and early adulthood, and persists throughout most of an individual’s life[13]. Moreover, it imposes a substantial economic burden on both society and families[14]. The pathogenesis of SCZ is currently unknown. It has been found that the development of SCZ is caused by the interaction of genetics, brain structure, pregnancy complications, and environmental factors[15]. Genetic predisposition plays a pivotal role in the etiology of SCZ, as evidenced by its remarkably high heritability estimate, which approaches 80%[15,16]. Additionally, environmental factors and stressors also substantially influence its development, including maternal immune system infections during pregnancy[17], advanced paternal age, childhood abuse[18], and exposure to substances like marijuana[19]. It is hypothesized that many genes undergo epigenetic modifications as a result of environmental exposures that have long-term effects, and that these modifications accumulate in the brain and other tissues during the development of individuals, thereby affecting genome function[15,20]. The diagnosis of SCZ is confirmed only if the patient meets the diagnostic criteria; however, this diagnosis is based on a subjective assessment by the clinician. To date, no reliable physical examination findings or biomarkers have been found to support this diagnostic process.

Depression refers to a common psychiatric disorder characterized by persistent sadness and a lack of interest or pleasure in activities. The core symptoms of MDD include hopelessness, social avoidance, insomnia, anxiety, cognitive and sexual dysfunction[21]. They are accompanied by a high degree of chronicity and a high rate of recurrence[22-24]. The pathogenesis of depression is intricate, involving neurotransmitters, hormonal mediation, and multilevel interactions between different regions of the brain. Neurotransmitters such as dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin play critical roles in this process, and dysfunction of these systems leads to altered neuroplasticity, enhanced inflammatory responses, and abnormal synaptic function, collectively contributing to the development and persistence of depressive symptoms[25].

Currently, medications such as ketamine can effectively control the symptoms of depression[26], but they are unable to cure the disorder. Patients experience relapse within a short period of time after discontinuing the medication. During relapses, patients may experience increased blood pressure, nausea, memory loss, gastrointestinal disorders, and recurrent fluctuations in mental status. Given the lack of clear, objective diagnostic criteria and biomarkers for MDD, three commonly used clinical symptom rating scales are available: The Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, the Beck De

BD is a group of highly clinically heterogeneous, multifactorial disorders characterized by recurrent cycles of depression (typical features), mania or hypomania, alternating episodes of common psychiatric disorders[27]. The etiology of BD remains elusive. A substantial body of research data indicates that genetic factors, psychosocial factors, biological factors, and an individual’s psychological state all exert a significant influence on the development of BD[28]. Moreover, the interactions among these factors contribute to the onset and progression of the disorder[28]. Among them, genetic factors account for a large proportion, and the heritability range of BD is between 70% and 90%[29]. However, due to the com

MiRNAs represent a class of evolutionarily conserved, small ncRNA molecules, typically comprising approximately 22 nucleotides in length[30]. They are present in both animal and plant cells, playing a crucial role in regulating cellular signaling and biological processes[15]. The biogenesis of miRNAs is initiated by RNA polymerase II, which transcribes miRNA genes to produce primary miRNAs[15]. These primary miRNAs are then processed into mature miRNAs, which can be found in various subcellular structures and may even be released via exosomes[30]. Mature miRNAs can bind to the 3’-untranslated regions of target mRNAs, leading to their degradation or translational repression, thereby controlling gene expression[15]. Alterations in miRNA expression play a crucial role in regulating genetic networks and signaling cascades. Moreover, abnormal miRNA expression is frequently associated with the development of various diseases[9]. Beyond diagnostics, miRNAs hold therapeutic potential due to their ability to modulate cellular functions involved in some diseases[31]. Additionally, the co-regulation of genes and pathways by multiple miRNAs forms a complex regulatory network that may underpin many human pathologies, suggesting a role for miRNAs in epigenetic regulation[32].

LncRNAs are a class of ncRNAs exceeding 200 nucleotides in length, lacking a significant open reading frame and thus minimal protein-coding capacity[33]. Their formation is multifaceted, arising from various pathways, including the independent transcription of introns, promoters, enhancer regions, and specific lncRNA genes in intergenic areas[34,35]. This diversity in generation mechanisms underpins their extensive biological functions. LncRNAs exert regulatory effects on gene expression at multiple levels, including chromatin remodeling, RNA modification, RNA stability regulation, transcriptional modulation, splicing control, and translation initiation. These regulatory actions of lncRNAs have a significant impact on cellular gene expression profiles[36-39]. LncRNAs are involved in key cellular processes related to physiology, and alterations in their expression are linked to diverse disease developments[40]. They participate in dosage compensation, transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulation, epigenetic control, and cellular differentiation[41-43]. Their subcellular localization correlates with their functional roles, particularly in nuclear functions, where they can regulate protein localization, abundance, and host gene expression[41-43]. Additionally, lncRNAs interact with DNA, RNA, or proteins to form complexes that modulate gene expression patterns[44]. Their expression is finely tuned and contributes to various gene expression regulatory mechanisms, including influencing the transcription of neighboring genes and participating in chromatin biology processes such as DNA replication and the response to DNA damage[33,45].

CircRNAs are widely expressed RNAs that do not have structures such as a 5’ terminal cap and a 3’ terminal polya

CircRNAs exhibit multiplicity through alternative splicing, generating diverse exon-intron structures from different genes[52]. With high efficiency, the circRNA structure can act as a template for roll-over replication, facilitating the ef

A multifaceted and intricate interplay across multiple molecular levels characterizes the pathogenesis of SCZ. Core contributors to its development include dysfunctional molecular pathways such as neuroinflammation, oxidative stress, and mitochondrial dysfunction, which collectively underpin the disorder’s etiology[57]. Furthermore, disruptions in synaptic function and abnormalities in neurodevelopmental processes, as well as genetic predisposition, significantly influence the progression of SCZ. Complementing these central factors, dysregulation of neurotransmitter systems, particularly dopamine and glutamate, plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis of SCZ, underscoring the integrative nature of its underlying mechanisms[25].

In recent years, epigenetic mechanisms, particularly miRNA-mediated post-transcriptional regulation, have made significant progress in understanding the molecular mechanisms of SCZ, providing an increasing wealth of evidence for elucidating the pathophysiological processes of the disease[58] (Table 1). For example, Zhao et al[59] found that miR-3653-3p was expressed at a low level in the peripheral blood of patients with SCZ. Perkins et al[60] detected miRNAs in the postmortem prefrontal cortex (PFC) of 13 SCZ patients by performing customized microarray analysis[60]. Comparing them with healthy controls (HCs), they identified 16 miRNAs that were differentially expressed. García-Cerro et al[4] observed differences in miR-132-3p transcript levels in plasma and post-mortem PFC tissues from a mouse model of SCZ. They found that SCZ patients had reduced levels of miR-21-5p in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs). Beveridge et al[61] analyzed 17 pairs of SCZ patients, finding overall elevated expression of miRNAs associated with SCZ in postmortem tissues of the superior temporal gyrus and dorsolateral PFC. The significance analysis of microarrays reported that a total of 59 miRNAs were upregulated[61]. Elevated levels of HOXA-AS2, Linc-ROR, MEG3, SPRY4-IT1, and UCA1 were found in SCZ patients’ blood compared to HCs[62]. When gene expression was assessed by gender, these lncRNAs were found to be significantly expressed in females[62]. This study suggests that gender-based lncRNA dysregulation exists in patients with SCZ, and thus, they may be used as diagnostic biomarkers.

| Ref. | Sample source | Samples | NcRNA | Method | Results |

| Miller et al[100], 2012 | Prefrontal cortical tissue | SCZ: 35; HCs: 34; BD: 31 | MiRNA | RT-qPCR | 483 miRNAs up |

| Du et al[94], 2019 | Exosome in blood | SCZ: 49; HCs: 46 | MiRNA | MiRNA-seq NGS | 18 miRNAs up |

| Zhao et al[59], 2023 | Peripheral blood | SCZ: 8; HCs: 15 | MiRNA | RT-qPCR | 41 miRNAs down; 35 miRNAs up |

| Liu et al[107], 2019 | PBMCs | SCZ: 32; HCs: 48 | LncRNA | RT-qPCR | The expression levels of CSMD1 are correlated with SCZ |

| Fallah et al[65], 2019 | Peripheral blood | SCZ: 60; HCs: 60 | LncRNA | RT-qPCR | 5 lncRNAs up |

| Teng et al[108], 2023 | SCZ postmortem brains | SCZ: 559; HCs: 936 | LncRNA | RNA-seq analysis; RT-qPCR | LncRNA-GOMAFU down |

| Zimmerman et al[79], 2020 | Human postmortem brain total RNA | SCZ: 34; HCs: 34 | CircRNA | RT-qPCR | CircHomer1a down |

| Mahmoudi et al[109], 2021 | PBMCs | SCZ: 39; HCs: 20 | CircRNA | RNA-seq analysis | 8762 circRNAs up; 55 circRNAs down |

| Huang et al[110], 2023 | Plasma | SCZ: 10; HCs: 8 | CircRNA | RT-qPCR; RNA-seq analysis | 1 circRNAs up; 234 circRNAs down |

Current research suggests that ncRNAs play a complex and critical role in the mechanisms of MDD, involving multiple biological processes, such as neuroinflammation, neuroplasticity, and apoptosis[63]. Wu et al[64] found that miR-144-5p expression was significantly reduced in the hippocampal dentate gyrus of a mouse model of chronic unpredictable stress. MiR-144-5p upregulation in the dentate gyrus ameliorated depressive behavior in chronic unpredictable stress mice[65]. MiR-144-5p was also found to be down-regulated in the serum of MDD patients and correlated with depressive symptoms[66]. Serum exosome-derived miR-144-5p levels were consistently reduced in MDD patients[64]. Ceylan et al[67] assessed the expression levels of miRNAs in the blood of 20 patients with MDD and 20 HCs by microarray technology. They found that five miRNAs (hsa-let-7a-5p, hsa-let-7d-5p, hsa-let-7f-5p, hsa-miR-24-3p, and hsa-miR-425-3p) were abnormally expressed in MDD patients. Camkurt et al[68] investigated miRNA expression levels in peripheral blood samples of 50 patients with MDD and 41 HCs. Four miRNAs exhibited significant alterations, and miR-451a may serve as a potential biomarker for depression[68]. Research has shown that miR-16 is associated with MDD by regulating the expression of the 5-hydroxytryptamine transporter protein gene[69]. The expression of miR-16 in patients’ CSF was significantly lower than that in the control group[69].

Cui et al[70] evaluated the association between lncRNA expression in PBMCs and the risk of suicide in patients with MDD using reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction. The results showed that the expression of six lncRNAs was significantly down-regulated and negatively correlated with the risk of suicide in patients with MDD[70]. The expression of lncRNAs in PBMCs may be helpful for clinicians to determine the risk of suicide in patients with MDD, so that they can provide timely intervention treatment and suicide prevention[70].

Dysregulation of circRNAs can contribute to neurotrophic signaling deficits and synaptic remodeling in depression by influencing central inflammatory responses and neuronal damage[71]. Wang et al[72] examined blood samples from 50 patients with MDD and 40 HCs. They discovered that the expression of circRNA protein tyrosine kinase 2 in PBMCs of MDD patients was decreased, which could assist in differentiating MDD patients from healthy individuals. Therefore, circRNA-homeodomain-interacting protein kinase-2 (circHIPK2) may be used as a potential biomarker for predicting and diagnosing MDD. The association between ncRNA and MDD is shown in Table 2.

| Ref. | Sample source | Samples | NcRNA | Method | Results |

| Wei et al[111], 2020 | Blood exosomes | MDD: 33; HCs: 46 | MiRNA | RT-qPCR | 24 miRNAs up; 14 miRNAs down |

| Ran et al[112], 2022 | Serum EVs | MDD: 9; HCs: 8 | MiRNA | RNA-seq analysis; western blotting | miR-450a-2-3p up |

| Burrows et al[113], 2024 | Peripheral blood | MDD: 41; HCs: 35 | MiRNA | RT-qPCR | MDD is associated with lower NEEV miR-93 expression |

| Liu et al[114], 2014 | Peripheral blood | MDD: 10; HCs:10 | LncRNA | RNA-seq analysis; RT-qPCR | 1556 lncRNA up; 441 lncRNA down |

| Cui et al[115], 2016 | Peripheral blood | MDD: 120; HCs: 63 | LncRNA | RT-qPCR | 6 lncRNAs down |

| Yrondi et al[116], 2021 | Peripheral blood | MDD: 201; HCs: 104 | LncRNA | RNA-seq analysis; genome-wide DNA methylation analysis | BASP1-AS1 up |

| Cui et al[117], 2016 | PBMCs | MDD: 30; HCs: 0 | CircRNA | RT-qPCR | 4 circRNAs up |

| Bu et al[118], 2021 | Peripheral blood | MDD: 83; HCs: 83 | CircRNA | RT-qPCR | hsa_circ_0126218 up |

| Yu et al[102], 2024 | Plasma | MDD: 81; HCs: 48 | CircRNA | RT-qPCR | circHIPK2 up |

The specific etiology of BD, a chronic mood disorder, remains largely unsolved. NcRNAs play a key role in the pathomechanism of BD. Increasing evidence suggests that lncRNAs are involved in many neurodevelopmental conditions, serving as potential therapeutic targets or biomarkers[73]. Camkurt et al[74] detected significantly elevated miR-107 and miR-125a-3p in PBMCs of 58 patients with BD compared to HCs. MiR-106a-5p and miR-107 were significantly associated with manic episodes compared to other miRNAs detected[74]. Kim et al[75] observed 15 miRNAs differentially expressed in postmortem brain tissue from the dorsolateral PFC of BD patients. The overexpressed miRNAs were all moderately to highly expressed and showed significant correlation with each other. Maffioletti et al[76] assessed the expression levels of miRNAs in the blood of 20 BD patients and 20 HCs using microarray technology. They found that five miRNAs (hsa-miR-140-3p, hsa-miR-30d-5p, hsa-miR-330-5p, hsa-miR-378a-5p, and hsa-miR-21-3p) were altered explicitly in BD patients. Tsai et al[77] found that miR-221-5p/carbonic anhydrase 1/matrix metalloproteinase 9 and miR-370-3p/phenylalanyl-tRNA synthetase beta subunit/proprotein convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 axes may play key roles in the pathomechanism of BD-II in a study of peripheral candidate miRNAs and protein biomarkers in 96 BD-II patients. Lee et al[78] found that miR7-5p, miR221-5p, and miR370-3p were significantly associated with brain-derived neurotrophic factor levels in all patients. Zimmerman et al[79] found that circHomer1a was a neuron-rich circRNA abundantly expressed in the frontal cortex and derived from HOMER1. CircRNAs expression analyses were carried out on post-mortem total brain RNA samples sourced from the orbital frontal cortex of 32 individuals diagnosed with BD[79]. The findings indicated that the expression levels of circHomer1a were significantly reduced in neuronal cultures generated from induced pluripotent stem cells[79]. The association between ncRNA and BD is shown in Table 3.

| Ref. | Sample source | Samples | NcRNA | Method | Results |

| Fiorentino et al[119], 2016 | Peripheral blood | BD: 2078; HCs: 1355 | MiRNA | RT-qPCR | A single recurrent variant in the vicinity of the miR-708 gene |

| Mola-Ali-Nejad et al[120], 2023 | Peripheral blood | BD: 50; HCs: 50 | LncRNA | RT-PCR | NKILA and COX2 down |

| Lin et al[121], 2021 | Post-mortem human; brain samples | BD: 13; HCs: 13 | CircRNA | RT-qPCR; RNA-seq analysis | 26 circRNAs up |

| Hosseini and Mokhtari[122], 2024 | Peripheral blood | BD: 50; HCs: 50 | LncRNA | qRT-PCR | HOXA-AS2 and MEG3 up |

| Zamani et al[123], 2023 | Peripheral blood | BD: 50; HCs: 50 | LncRNA | RT-qPCR | FOXD3-AS1 and GAS5 up |

| Maffioletti et al[76], 2016 | Peripheral blood | BD: 20; HCs: 20 | MiRNA | Microarray | 5 miRNAs up; 2 miRNAs down |

| Ceylan et al[67], 2020 | Peripheral blood | BD: 69; HCs: 41 | MiRNA | RT-qPCR | 3 miRNAs down; miR-185-5p up |

| Zimmerman et al[79], 2020 | Human postmortem brain; total RNA samples | BD: 32; HCs: 34 | CircRNA | RT-qPCR | CircHomer1a down |

| Mahmoudi et al[109], 2021 | PBMCs | BD: 39; HCs: 20 | CircRNA | RNA-seq | 55 circRNAs down |

EVs are a diverse group of subcellular, closed membrane structures with a phospholipid bilayer, which are secreted by cells and detectable in various body fluids, such as blood, urine, and saliva[80]. These vesicles, typically having diameters ranging from 30 nm to 5000 nm, play a crucial and irreplaceable role in mediating communication between the external environment and organisms, as well as interactions among diverse cell types[80]. They have now gained extensive recognition as pivotal carriers of cellular signaling. EVs can be categorized into subgroups, including exosomes (30-

EVs can be produced by a wide range of organisms, spanning from prokaryotes to higher eukaryotes[83]. These vesicles play essential physiological and pathological roles in organisms. Surprisingly, almost all cell types can produce EVs[83]. Bacteria in prokaryotes can release EVs by outgrowth, whereas cells in eukaryotes produce EVs by endocytosis and cytotoxicity in higher eukaryotes, such as mammals. EV production is closely linked to several physiological processes, including the immune response, cellular communication, and waste removal[84].

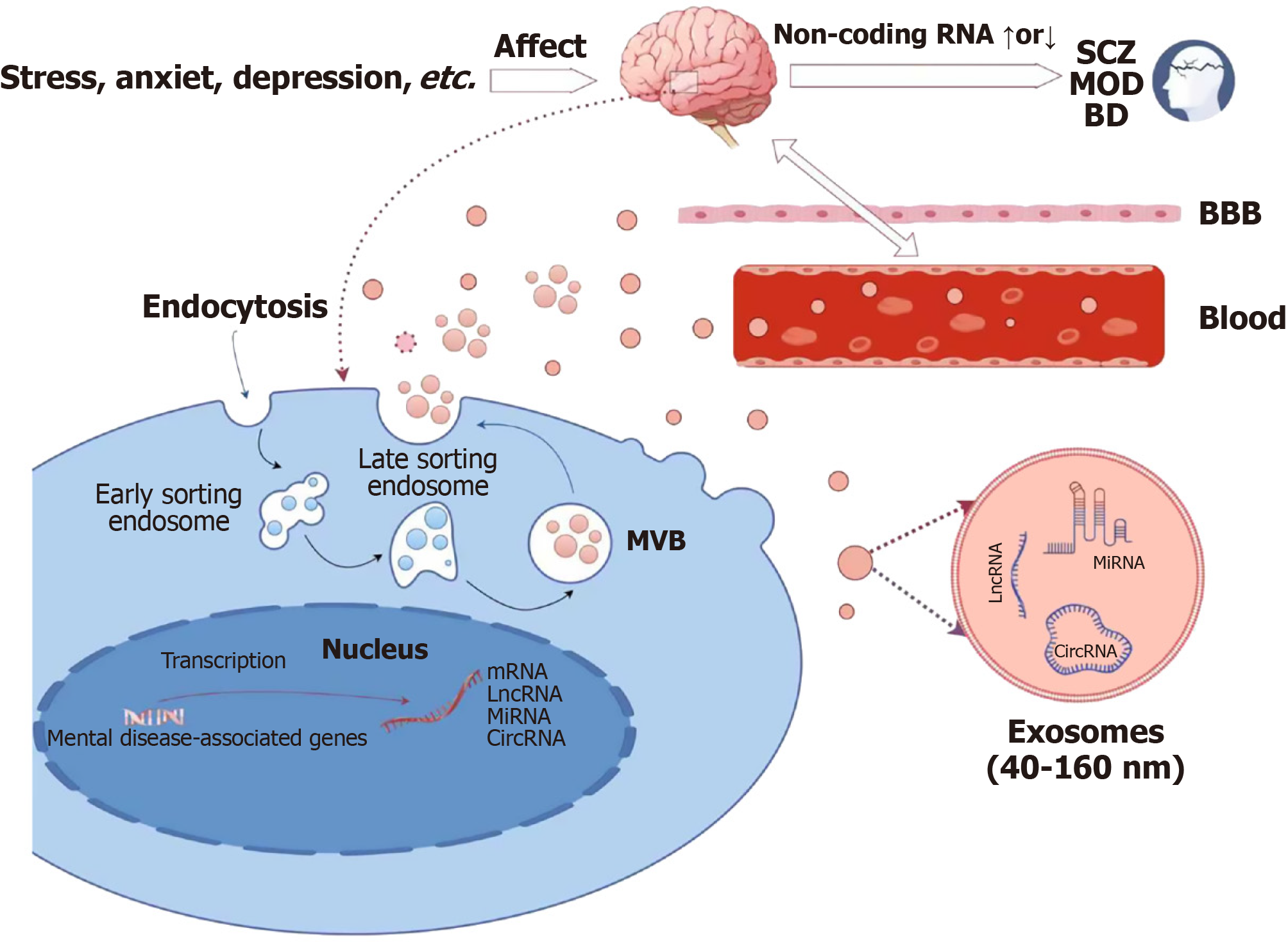

The process of EV development varies depending on the type, but generally involves the following steps. Initially, the cell membrane invaginates to form primary endosomes, which then develop into more mature secondary endosomes. These secondary endosomes then evolve into more mature secondary endosomes, which eventually develop into multivesicular bodies (MVBs) containing multiple small vesicles. During the formation of these vesicles, exosomes, which are primarily derived from MVBs, are released to the outside of the cell by fusion with the cytoplasmic membrane[85]. In addition, microvesicles are formed by budding and shedding directly from the cytoplasmic membrane. This process also enables MVB to bind to other organelles, such as lysosomes or autophagosomes, and participate in the degradation and recycling of substances[86]. This ubiquitous phenomenon suggests that EVs have a wide range of essential functions in the biological world. Due to their disease-specific and highly stable EVs and their contents, they may also serve as ideal biomarkers for various diseases[87,88].

EVs are involved in neurological disease processes by carrying a variety of biologically active molecules (e.g., ncRNAs) for intercellular delivery[12]. These ncRNAs can be selectively loaded and transported by exosomes to regulate processes such as cell growth, differentiation, development, and apoptosis. Due to the load diversity of exosomes and their ability to bi-directionally penetrate the blood-brain barrier, they have emerged as potential non-invasive biomarkers for the screening, diagnosis, and treatment of brain disorders[89,90]. Therefore, targeting strategies that specifically target ncRNAs in EVs may become a promising therapeutic option. Krylova and Feng[91] found that ncRNAs are present in blood, CSF, saliva, and urine, and that they can be released into the circulation in free form or packaged in exosomes. Although a large proportion of ncRNAs are composed of ribosomal RNAs and transfer RNAs involved in the translation process, it is increasingly recognized that non-coding products contain a wide range of species associated with core biological processes and diseases. To date, the pathology and action mechanisms of most psychiatric disorders are unclear. The pathogenic factors of psychiatric disorders primarily encompass neuroinflammation and dysregulation of the internal environmental homeostasis within the central nervous system. Remarkably, EVs have been shown to have a significant impact on these pathological processes (Figure 1). EVs are capable of mapping the immediate state of the brain and specific clinical phenomena, such as non-suicidal self-mutilation and cognitive dysfunctions[92].

Some studies found miRNA dysregulation in EVs of brain tissue[75], CSF[69], and peripheral blood[93] after death in patients with SCZ or other psychiatric disorders. For example, Du et al[94] were the first to screen 18 differentially expressed miRNAs from blood exosomes of SCZ patients, suggesting that EV-derived ncRNAs hold greater potential for clinical application. Some studies have suggested that specific miRNAs in exosomes from blood may contribute to the pathogenesis of SCZ, including abnormalities in protein glycosylation, neurotransmitter biosynthesis, and dendritic development, which may lead to the remodeling of the brain's structural and functional phenotype[95]. For example, miR-132 in EVs was decreased in SCZ and increased in MDD and BD[95], suggesting different pathological mechanisms between BD and SCZ. Additionally, miR-132 has a broad range of effects on the nervous system[96]. It not only controls neuronal differentiation, maturation, and function, but also profoundly intervenes in axon extension and neuroplasticity, which in turn protects neurogenesis and related memory functions in the hippocampal region from defects[96]. MiR-130b and miR-193a-3p were found to be upregulated in SCZ patients[63]. These miRNAs were involved in pathological mechanisms, including the dysregulation of the protein kinase B pathway and the production of cytokines in psychiatric patients[63]. This involvement provides a plausible explanation for the overlapping symptom profiles observed across various psychiatric disorders[63].

Over the past decade, there has been an increasing effort to develop exosome-based biomarkers to fill the gap in the early diagnosis of human psychiatric disorders. NcRNAs in EVs are stable in body fluids and can be used as biomarkers for disease diagnosis, prognosis, and response to therapy. Abnormally expressed miRNAs, lncRNAs, and circRNAs offer new ideas and approaches for the development of minimally invasive diagnostic tests for early detection and monitoring of brain diseases. In addition, the development of novel therapeutic interventions aimed at improving clinical outcomes is expected for aberrantly expressed ncRNAs[25].

Recent studies on three major psychiatric disorders have revealed key findings of abnormal ncRNA expression in patients with SCZ, MDD, and BD. Expression alterations of miRNAs such as miR-132, miR-144-5p, and miR-16 were detected in patients’ blood, CSF, or brain tissue[65,69,96]. Specific miRNAs, such as miR-132, are downregulated in SCZ but upregulated in MDD and BD, suggesting their involvement in disease-specific pathways. Furthermore, these miRNAs may serve as biomarkers for distinct subtypes within the same disorder[97]. The phenomenon of the same miRNA exhibiting differential expression across disorders reflects significant molecular heterogeneity and overlapping pathological mechanisms among psychiatric conditions. These discrepancies may stem from multiple factors, including differences in sample sources (brain tissue, blood) or methodological variations (reverse transcription-quantitative polymerase chain reaction, RNA-seq analysis).

The discovery of the roles of ncRNAs in psychiatric disorders such as SCZ, MDD, and BD has deepened our understanding of disease mechanisms and opened new avenues for therapeutic exploration[74,98]. NcRNAs mechanistically influence pathophysiological processes through diverse mechanisms. For instance, miR-132, a well-studied miRNA, regulates synaptic plasticity by modulating dendritic spine formation and neuronal connectivity, which are critical for cognitive function and are often impaired in psychiatric disorders[99-101]. Similarly, Yu et al[102] found that circHIPK2 was involved in depression by inducing hippocampal astrocyte dysfunction in depressed mice, which resulted in high plasma and hippocampal expression in depressed mice, and circHIPK2 levels decreased with the alleviation of depressive symptoms in mice. Further studies showed that the expression of circHIPK2 was significantly increased in the plasma of MDD patients and may be involved in a variety of signal pathways, including the P53 signal pathway, the AMP-activated protein kinase signal pathway, the tumor necrosis factor signal pathway, and the Ras signal pathway, which are thought to regulate glial cell function[103].

The levels of ncRNAs in EVs often reflect disease progression and severity. For example, specific miRNAs exhibit altered expression at distinct stages of SCZ, ranging from early mild cognitive deficits to later, more severe clinical manifestations[98]. Similarly, the up- or downregulation of ncRNAs during various pathological processes underscores their potential as therapeutic targets[92]. These findings suggest that ncRNAs could revolutionize the diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment of psychiatric disorders.

EVs play dual biological roles: They serve as carriers of disease-specific ncRNAs for early diagnosis and as low-immunogenicity, targeted delivery systems for therapeutic nucleic acids and small-molecule drugs[104]. Their ability to cross the blood-brain barrier and deliver therapeutic molecules, such as neurotrophic factors or CRISPR-Cas9 components, to specific brain regions overcomes the limitations of conventional drug delivery methods[89]. This unique property positions EVs as a promising tool for treating central nervous system diseases.

Currently, the research and application of ncRNAs in EVs face multiple challenges. For example, the diversity of exosome isolation methods results in significant differences in purity, concentration, and isoform composition, complicating direct comparisons across studies[105,106]. Additionally, complex body fluids like blood contain contaminants such as lipoproteins and protein aggregates, which are similar in size and density to exosomes and can interfere with ncRNA sequencing analyses, leading to false-positive or false-negative results. Therefore, replicated validation in larger, multi-ethnic cohorts is essential to advance clinical translation.

While existing studies have provided initial insights into the link between ncRNAs and psychiatric disorders, these findings require further exploration and validation to establish a robust scientific foundation. First, the heterogeneity of EVs and the absence of standardized isolation and characterization methods present significant challenges for reproducibility and cross-study comparisons. Second, the limited understanding of the specific functional roles of ncRNAs in psychiatric disorders underscores the need for more in-depth mechanistic investigations. Finally, the current findings necessitate validation in larger, longitudinal cohorts to confirm their translational potential and clinical applicability. Addressing these limitations will be critical for advancing the field and realizing the therapeutic and diagnostic promise of ncRNAs in psychiatric disorders.

NcRNAs play a pivotal role in psychiatric disorders by regulating gene expression and mediating key biological pathways, offering novel insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying these conditions. The analysis of small and long RNA profiles in serum and plasma-derived exosomes has identified specific miRNAs, circRNAs, and lncRNAs as potential biomarkers for major psychiatric disorders. Aberrant expression of EV-associated ncRNAs has been consistently observed across various psychiatric disorders, highlighting their utility as a promising source of disease biomarkers. These findings not only enhance our understanding of the molecular basis of psychiatric disorders but also pave the way for the development of innovative diagnostic tools and therapeutic strategies. Further research is essential to validate these biomarkers and explore their clinical applications, ultimately improving patient outcomes.

| 1. | Ferrari AJ, Saha S, McGrath JJ, Norman R, Baxter AJ, Vos T, Whiteford HA. Health states for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder within the Global Burden of Disease 2010 Study. Popul Health Metr. 2012;10:16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Ferrari AJ, Baxter AJ, Whiteford HA. A systematic review of the global distribution and availability of prevalence data for bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2011;134:1-13. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 76] [Cited by in RCA: 68] [Article Influence: 4.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Ferrari AJ, Somerville AJ, Baxter AJ, Norman R, Patten SB, Vos T, Whiteford HA. Global variation in the prevalence and incidence of major depressive disorder: a systematic review of the epidemiological literature. Psychol Med. 2013;43:471-481. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 917] [Cited by in RCA: 834] [Article Influence: 64.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | García-Cerro S, Gómez-Garrido A, Garcia G, Crespo-Facorro B, Brites D. Exploratory Analysis of MicroRNA Alterations in a Neurodevelopmental Mouse Model for Autism Spectrum Disorder and Schizophrenia. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25:2786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Zong H, Yu W, Lai H, Chen B, Zhang H, Zhao J, Huang S, Li Y. Extracellular vesicles long RNA profiling identifies abundant mRNA, circRNA and lncRNA in human bile as potential biomarkers for cancer diagnosis. Carcinogenesis. 2023;44:671-681. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Juźwik CA, S Drake S, Zhang Y, Paradis-Isler N, Sylvester A, Amar-Zifkin A, Douglas C, Morquette B, Moore CS, Fournier AE. microRNA dysregulation in neurodegenerative diseases: A systematic review. Prog Neurobiol. 2019;182:101664. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 169] [Cited by in RCA: 334] [Article Influence: 47.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Li K, Wang Z. lncRNA NEAT1: Key player in neurodegenerative diseases. Ageing Res Rev. 2023;86:101878. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Tan L, Yu JT, Tan L. Causes and Consequences of MicroRNA Dysregulation in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Mol Neurobiol. 2015;51:1249-1262. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 103] [Article Influence: 8.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Ma YM, Zhao L. Mechanism and Therapeutic Prospect of miRNAs in Neurodegenerative Diseases. Behav Neurol. 2023;2023:8537296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Zhang J, Li S, Li L, Li M, Guo C, Yao J, Mi S. Exosome and exosomal microRNA: trafficking, sorting, and function. Genomics Proteomics Bioinformatics. 2015;13:17-24. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1443] [Cited by in RCA: 1643] [Article Influence: 149.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Nikanjam M, Kato S, Kurzrock R. Liquid biopsy: current technology and clinical applications. J Hematol Oncol. 2022;15:131. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 586] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Record M, Carayon K, Poirot M, Silvente-Poirot S. Exosomes as new vesicular lipid transporters involved in cell-cell communication and various pathophysiologies. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2014;1841:108-120. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 502] [Cited by in RCA: 635] [Article Influence: 48.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Solmi M, Seitidis G, Mavridis D, Correll CU, Dragioti E, Guimond S, Tuominen L, Dargél A, Carvalho AF, Fornaro M, Maes M, Monaco F, Song M, Il Shin J, Cortese S. Incidence, prevalence, and global burden of schizophrenia - data, with critical appraisal, from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2019. Mol Psychiatry. 2023;28:5319-5327. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 313] [Cited by in RCA: 291] [Article Influence: 97.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Keshavan MS, Collin G, Guimond S, Kelly S, Prasad KM, Lizano P. Neuroimaging in Schizophrenia. Neuroimaging Clin N Am. 2020;30:73-83. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 37] [Cited by in RCA: 87] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Khavari B, Cairns MJ. Epigenomic Dysregulation in Schizophrenia: In Search of Disease Etiology and Biomarkers. Cells. 2020;9:1837. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 26] [Cited by in RCA: 74] [Article Influence: 12.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Owen MJ, Sawa A, Mortensen PB. Schizophrenia. Lancet. 2016;388:86-97. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1067] [Cited by in RCA: 1369] [Article Influence: 136.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 17. | Lewis SW, Murray RM. Obstetric complications, neurodevelopmental deviance, and risk of schizophrenia. J Psychiatr Res. 1987;21:413-421. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 339] [Cited by in RCA: 290] [Article Influence: 7.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Jester DJ, Thomas ML, Sturm ET, Harvey PD, Keshavan M, Davis BJ, Saxena S, Tampi R, Leutwyler H, Compton MT, Palmer BW, Jeste DV. Review of Major Social Determinants of Health in Schizophrenia-Spectrum Psychotic Disorders: I. Clinical Outcomes. Schizophr Bull. 2023;49:837-850. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 16] [Cited by in RCA: 79] [Article Influence: 26.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Cheng W, Parker N, Karadag N, Koch E, Hindley G, Icick R, Shadrin A, O'Connell KS, Bjella T, Bahrami S, Rahman Z, Tesfaye M, Jaholkowski P, Rødevand L, Holen B, Lagerberg TV, Steen NE, Djurovic S, Dale AM, Frei O, Smeland OB, Andreassen OA. The relationship between cannabis use, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder: a genetically informed study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2023;10:441-451. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Article Influence: 11.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Richetto J, Meyer U. Epigenetic Modifications in Schizophrenia and Related Disorders: Molecular Scars of Environmental Exposures and Source of Phenotypic Variability. Biol Psychiatry. 2021;89:215-226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 56] [Cited by in RCA: 121] [Article Influence: 24.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Kim YK. Molecular neurobiology of major depressive disorder. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2016;64:275-276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Kennis M, Gerritsen L, van Dalen M, Williams A, Cuijpers P, Bockting C. Prospective biomarkers of major depressive disorder: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25:321-338. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 138] [Cited by in RCA: 293] [Article Influence: 48.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Hardeveld F, Spijker J, De Graaf R, Hendriks SM, Licht CM, Nolen WA, Penninx BW, Beekman AT. Recurrence of major depressive disorder across different treatment settings: results from the NESDA study. J Affect Disord. 2013;147:225-231. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 73] [Article Influence: 5.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Burcusa SL, Iacono WG. Risk for recurrence in depression. Clin Psychol Rev. 2007;27:959-985. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 775] [Cited by in RCA: 731] [Article Influence: 38.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ilieva MS. Non-Coding RNAs in Neurological and Neuropsychiatric Disorders: Unraveling the Hidden Players in Disease Pathogenesis. Cells. 2024;13:1063. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 48] [Article Influence: 24.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Berman RM, Cappiello A, Anand A, Oren DA, Heninger GR, Charney DS, Krystal JH. Antidepressant effects of ketamine in depressed patients. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;47:351-354. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2441] [Cited by in RCA: 2858] [Article Influence: 109.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Jones GH, Vecera CM, Pinjari OF, Machado-Vieira R. Inflammatory signaling mechanisms in bipolar disorder. J Biomed Sci. 2021;28:45. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 45] [Cited by in RCA: 84] [Article Influence: 16.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Lichtenstein P, Yip BH, Björk C, Pawitan Y, Cannon TD, Sullivan PF, Hultman CM. Common genetic determinants of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder in Swedish families: a population-based study. Lancet. 2009;373:234-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1472] [Cited by in RCA: 1516] [Article Influence: 89.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Carvalho AF, Firth J, Vieta E. Bipolar Disorder. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:58-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 195] [Cited by in RCA: 366] [Article Influence: 61.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (6)] |

| 30. | Saliminejad K, Khorram Khorshid HR, Soleymani Fard S, Ghaffari SH. An overview of microRNAs: Biology, functions, therapeutics, and analysis methods. J Cell Physiol. 2019;234:5451-5465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1431] [Cited by in RCA: 1458] [Article Influence: 208.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Jiang M, Jike Y, Liu K, Gan F, Zhang K, Xie M, Zhang J, Chen C, Zou X, Jiang X, Dai Y, Chen W, Qiu Y, Bo Z. Exosome-mediated miR-144-3p promotes ferroptosis to inhibit osteosarcoma proliferation, migration, and invasion through regulating ZEB1. Mol Cancer. 2023;22:113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 131] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Diener C, Keller A, Meese E. Emerging concepts of miRNA therapeutics: from cells to clinic. Trends Genet. 2022;38:613-626. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 664] [Article Influence: 166.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Cao J. The functional role of long non-coding RNAs and epigenetics. Biol Proced Online. 2014;16:11. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 217] [Cited by in RCA: 271] [Article Influence: 22.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Wu H, Yang L, Chen LL. The Diversity of Long Noncoding RNAs and Their Generation. Trends Genet. 2017;33:540-552. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 173] [Cited by in RCA: 297] [Article Influence: 33.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Bridges MC, Daulagala AC, Kourtidis A. LNCcation: lncRNA localization and function. J Cell Biol. 2021;220:e202009045. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 528] [Cited by in RCA: 1110] [Article Influence: 222.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Chow J, Heard E. X inactivation and the complexities of silencing a sex chromosome. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009;21:359-366. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 168] [Cited by in RCA: 153] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Leeb M, Steffen PA, Wutz A. X chromosome inactivation sparked by non-coding RNAs. RNA Biol. 2009;6:94-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 32] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Wang X, Arai S, Song X, Reichart D, Du K, Pascual G, Tempst P, Rosenfeld MG, Glass CK, Kurokawa R. Induced ncRNAs allosterically modify RNA-binding proteins in cis to inhibit transcription. Nature. 2008;454:126-130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 805] [Cited by in RCA: 780] [Article Influence: 43.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Martianov I, Ramadass A, Serra Barros A, Chow N, Akoulitchev A. Repression of the human dihydrofolate reductase gene by a non-coding interfering transcript. Nature. 2007;445:666-670. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 608] [Cited by in RCA: 579] [Article Influence: 30.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Statello L, Guo CJ, Chen LL, Huarte M. Gene regulation by long non-coding RNAs and its biological functions. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2021;22:96-118. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3257] [Cited by in RCA: 3443] [Article Influence: 688.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Chen LL. Linking Long Noncoding RNA Localization and Function. Trends Biochem Sci. 2016;41:761-772. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 587] [Cited by in RCA: 808] [Article Influence: 80.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Tong C, Yin Y. Localization of RNAs in the nucleus: cis- and trans- regulation. RNA Biol. 2021;18:2073-2086. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Braunschweig U, Barbosa-Morais NL, Pan Q, Nachman EN, Alipanahi B, Gonatopoulos-Pournatzis T, Frey B, Irimia M, Blencowe BJ. Widespread intron retention in mammals functionally tunes transcriptomes. Genome Res. 2014;24:1774-1786. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 450] [Cited by in RCA: 511] [Article Influence: 42.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Yap K, Lim ZQ, Khandelia P, Friedman B, Makeyev EV. Coordinated regulation of neuronal mRNA steady-state levels through developmentally controlled intron retention. Genes Dev. 2012;26:1209-1223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 197] [Cited by in RCA: 236] [Article Influence: 16.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Irwin AB, Bahabry R, Lubin FD. A putative role for lncRNAs in epigenetic regulation of memory. Neurochem Int. 2021;150:105184. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Xu Y, Han J, Zhang X, Zhang X, Song J, Gao Z, Qian H, Jin J, Liang Z. Exosomal circRNAs in gastrointestinal cancer: Role in occurrence, development, diagnosis and clinical application (Review). Oncol Rep. 2024;51:19. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Ashwal-Fluss R, Meyer M, Pamudurti NR, Ivanov A, Bartok O, Hanan M, Evantal N, Memczak S, Rajewsky N, Kadener S. circRNA biogenesis competes with pre-mRNA splicing. Mol Cell. 2014;56:55-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1766] [Cited by in RCA: 2432] [Article Influence: 202.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Li Z, Huang C, Bao C, Chen L, Lin M, Wang X, Zhong G, Yu B, Hu W, Dai L, Zhu P, Chang Z, Wu Q, Zhao Y, Jia Y, Xu P, Liu H, Shan G. Exon-intron circular RNAs regulate transcription in the nucleus. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2015;22:256-264. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1619] [Cited by in RCA: 2303] [Article Influence: 209.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Yang Y, Fan X, Mao M, Song X, Wu P, Zhang Y, Jin Y, Yang Y, Chen LL, Wang Y, Wong CC, Xiao X, Wang Z. Extensive translation of circular RNAs driven by N(6)-methyladenosine. Cell Res. 2017;27:626-641. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 960] [Cited by in RCA: 1470] [Article Influence: 163.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Yang L, Wilusz JE, Chen LL. Biogenesis and Regulatory Roles of Circular RNAs. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2022;38:263-289. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 44] [Cited by in RCA: 219] [Article Influence: 54.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Guo JU, Agarwal V, Guo H, Bartel DP. Expanded identification and characterization of mammalian circular RNAs. Genome Biol. 2014;15:409. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1021] [Cited by in RCA: 1308] [Article Influence: 109.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | Zhu G, Chang X, Kang Y, Zhao X, Tang X, Ma C, Fu S. CircRNA: A novel potential strategy to treat thyroid cancer (Review). Int J Mol Med. 2021;48:201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 11.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Lasda E, Parker R. Circular RNAs: diversity of form and function. RNA. 2014;20:1829-1842. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 830] [Cited by in RCA: 964] [Article Influence: 80.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Jeck WR, Sorrentino JA, Wang K, Slevin MK, Burd CE, Liu J, Marzluff WF, Sharpless NE. Circular RNAs are abundant, conserved, and associated with ALU repeats. RNA. 2013;19:141-157. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3481] [Cited by in RCA: 3534] [Article Influence: 271.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 55. | Suzuki H, Zuo Y, Wang J, Zhang MQ, Malhotra A, Mayeda A. Characterization of RNase R-digested cellular RNA source that consists of lariat and circular RNAs from pre-mRNA splicing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2006;34:e63. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 398] [Cited by in RCA: 553] [Article Influence: 27.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Rybak-Wolf A, Stottmeister C, Glažar P, Jens M, Pino N, Giusti S, Hanan M, Behm M, Bartok O, Ashwal-Fluss R, Herzog M, Schreyer L, Papavasileiou P, Ivanov A, Öhman M, Refojo D, Kadener S, Rajewsky N. Circular RNAs in the Mammalian Brain Are Highly Abundant, Conserved, and Dynamically Expressed. Mol Cell. 2015;58:870-885. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1370] [Cited by in RCA: 1874] [Article Influence: 170.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Carpenter WT Jr, Buchanan RW. Schizophrenia. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:681-690. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 424] [Cited by in RCA: 384] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 58. | Cao T, Zhen XC. Dysregulation of miRNA and its potential therapeutic application in schizophrenia. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2018;24:586-597. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Zhao XL, Liu YL, Long Q, Zhang YQ, You X, Guo ZY, Cao X, Yu L, Qin FY, Teng ZW, Zeng Y. Abnormal expression of miR-3653-3p, caspase 1, IL-1β in peripheral blood of schizophrenia. BMC Psychiatry. 2023;23:822. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Perkins DO, Jeffries CD, Jarskog LF, Thomson JM, Woods K, Newman MA, Parker JS, Jin J, Hammond SM. microRNA expression in the prefrontal cortex of individuals with schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 400] [Cited by in RCA: 433] [Article Influence: 22.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Beveridge NJ, Gardiner E, Carroll AP, Tooney PA, Cairns MJ. Schizophrenia is associated with an increase in cortical microRNA biogenesis. Mol Psychiatry. 2010;15:1176-1189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 319] [Cited by in RCA: 369] [Article Influence: 23.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Fallah H, Azari I, Neishabouri SM, Oskooei VK, Taheri M, Ghafouri-Fard S. Sex-specific up-regulation of lncRNAs in peripheral blood of patients with schizophrenia. Sci Rep. 2019;9:12737. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 33] [Cited by in RCA: 40] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Kong L, Zhang D, Huang S, Lai J, Lu L, Zhang J, Hu S. Extracellular Vesicles in Mental Disorders: A State-of-art Review. Int J Biol Sci. 2023;19:1094-1109. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 33] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Wu X, Zhang Y, Wang P, Li X, Song Z, Wei C, Zhang Q, Luo B, Liu Z, Yang Y, Ren Z, Liu H. Clinical and preclinical evaluation of miR-144-5p as a key target for major depressive disorder. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2023;29:3598-3611. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 65. | Du Y, Tan WL, Chen L, Yang ZM, Li XS, Xue X, Cai YS, Cheng Y. Exosome Transplantation From Patients With Schizophrenia Causes Schizophrenia-Relevant Behaviors in Mice: An Integrative Multi-omics Data Analysis. Schizophr Bull. 2021;47:1288-1299. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 56] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 66. | Sundquist K, Memon AA, Palmér K, Sundquist J, Wang X. Inflammatory proteins and miRNA-144-5p in patients with depression, anxiety, or stress- and adjustment disorders after psychological treatment. Cytokine. 2021;146:155646. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 3.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Ceylan D, Tufekci KU, Keskinoglu P, Genc S, Özerdem A. Circulating exosomal microRNAs in bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2020;262:99-107. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 57] [Article Influence: 9.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | Camkurt MA, Acar Ş, Coşkun S, Güneş M, Güneş S, Yılmaz MF, Görür A, Tamer L. Comparison of plasma MicroRNA levels in drug naive, first episode depressed patients and healthy controls. J Psychiatr Res. 2015;69:67-71. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 68] [Cited by in RCA: 99] [Article Influence: 9.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Song MF, Dong JZ, Wang YW, He J, Ju X, Zhang L, Zhang YH, Shi JF, Lv YY. CSF miR-16 is decreased in major depression patients and its neutralization in rats induces depression-like behaviors via a serotonin transmitter system. J Affect Disord. 2015;178:25-31. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Cui X, Niu W, Kong L, He M, Jiang K, Chen S, Zhong A, Li W, Lu J, Zhang L. Long noncoding RNA expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells and suicide risk in Chinese patients with major depressive disorder. Brain Behav. 2017;7:e00711. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Huang X, Luo YL, Mao YS, Ji JL. The link between long noncoding RNAs and depression. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2017;73:73-78. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 75] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Wang K, Yang Y, Wang Y, Jiang Z, Fang S. CircPTK2 may be associated with depressive-like behaviors by influencing miR-182-5p. Behav Brain Res. 2024;462:114870. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | D'haene E, Jacobs EZ, Volders PJ, De Meyer T, Menten B, Vergult S. Identification of long non-coding RNAs involved in neuronal development and intellectual disability. Sci Rep. 2016;6:28396. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 38] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 4.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Camkurt MA, Karababa İF, Erdal ME, Kandemir SB, Fries GR, Bayazıt H, Ay ME, Kandemir H, Ay ÖI, Coşkun S, Çiçek E, Selek S. MicroRNA dysregulation in manic and euthymic patients with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2020;261:84-90. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Kim AH, Reimers M, Maher B, Williamson V, McMichael O, McClay JL, van den Oord EJ, Riley BP, Kendler KS, Vladimirov VI. MicroRNA expression profiling in the prefrontal cortex of individuals affected with schizophrenia and bipolar disorders. Schizophr Res. 2010;124:183-191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 218] [Cited by in RCA: 247] [Article Influence: 15.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 76. | Maffioletti E, Cattaneo A, Rosso G, Maina G, Maj C, Gennarelli M, Tardito D, Bocchio-Chiavetto L. Peripheral whole blood microRNA alterations in major depression and bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2016;200:250-258. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 114] [Cited by in RCA: 146] [Article Influence: 14.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 77. | Tsai KW, Yang YF, Wang LJ, Pan CC, Chang CH, Chiang YC, Wang TY, Lu RB, Lee SY. Correlation of potential diagnostic biomarkers (circulating miRNA and protein) of bipolar II disorder. J Psychiatr Res. 2024;172:254-260. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 78. | Lee SY, Wang TY, Lu RB, Wang LJ, Chang CH, Chiang YC, Tsai KW. Peripheral BDNF correlated with miRNA in BD-II patients. J Psychiatr Res. 2021;136:184-189. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 79. | Zimmerman AJ, Hafez AK, Amoah SK, Rodriguez BA, Dell'Orco M, Lozano E, Hartley BJ, Alural B, Lalonde J, Chander P, Webster MJ, Perlis RH, Brennand KJ, Haggarty SJ, Weick J, Perrone-Bizzozero N, Brigman JL, Mellios N. A psychiatric disease-related circular RNA controls synaptic gene expression and cognition. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25:2712-2727. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 102] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 21.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 80. | Collado A, Gan L, Tengbom J, Kontidou E, Pernow J, Zhou Z. Extracellular vesicles and their non-coding RNA cargos: Emerging players in cardiovascular disease. J Physiol. 2023;601:4989-5009. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 7.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 81. | Chen J, Lin JJ, Wang W, Huang H, Pan Z, Ye G, Dong S, Lin Y, Lin C, Huang Q. EV-COMM: A database of interspecies and intercellular interactions mediated by extracellular vesicles. J Extracell Vesicles. 2024;13:e12442. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 82. | Saheera S, Jani VP, Witwer KW, Kutty S. Extracellular vesicle interplay in cardiovascular pathophysiology. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2021;320:H1749-H1761. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 29] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 83. | Yáñez-Mó M, Siljander PR, Andreu Z, Zavec AB, Borràs FE, Buzas EI, Buzas K, Casal E, Cappello F, Carvalho J, Colás E, Cordeiro-da Silva A, Fais S, Falcon-Perez JM, Ghobrial IM, Giebel B, Gimona M, Graner M, Gursel I, Gursel M, Heegaard NH, Hendrix A, Kierulf P, Kokubun K, Kosanovic M, Kralj-Iglic V, Krämer-Albers EM, Laitinen S, Lässer C, Lener T, Ligeti E, Linē A, Lipps G, Llorente A, Lötvall J, Manček-Keber M, Marcilla A, Mittelbrunn M, Nazarenko I, Nolte-'t Hoen EN, Nyman TA, O'Driscoll L, Olivan M, Oliveira C, Pállinger É, Del Portillo HA, Reventós J, Rigau M, Rohde E, Sammar M, Sánchez-Madrid F, Santarém N, Schallmoser K, Ostenfeld MS, Stoorvogel W, Stukelj R, Van der Grein SG, Vasconcelos MH, Wauben MH, De Wever O. Biological properties of extracellular vesicles and their physiological functions. J Extracell Vesicles. 2015;4:27066. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3959] [Cited by in RCA: 4405] [Article Influence: 400.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 84. | Najafi S, Majidpoor J, Mortezaee K. Extracellular vesicle-based drug delivery in cancer immunotherapy. Drug Deliv Transl Res. 2023;13:2790-2806. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 36] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 85. | Perrin P, Janssen L, Janssen H, van den Broek B, Voortman LM, van Elsland D, Berlin I, Neefjes J. Retrofusion of intralumenal MVB membranes parallels viral infection and coexists with exosome release. Curr Biol. 2021;31:3884-3893.e4. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 86. | Eitan E, Suire C, Zhang S, Mattson MP. Impact of lysosome status on extracellular vesicle content and release. Ageing Res Rev. 2016;32:65-74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 128] [Cited by in RCA: 209] [Article Influence: 20.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 87. | Park J, Kim NE, Yoon H, Shin CM, Kim N, Lee DH, Park JY, Choi CH, Kim JG, Kim YK, Shin TS, Yang J, Park YS. Fecal Microbiota and Gut Microbe-Derived Extracellular Vesicles in Colorectal Cancer. Front Oncol. 2021;11:650026. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 65] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 88. | Zhang B, Zhao J, Jiang M, Peng D, Dou X, Song Y, Shi J. The Potential Role of Gut Microbial-Derived Exosomes in Metabolic-Associated Fatty Liver Disease: Implications for Treatment. Front Immunol. 2022;13:893617. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 5.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 89. | Dutta S, Hornung S, Taha HB, Bitan G. Biomarkers for parkinsonian disorders in CNS-originating EVs: promise and challenges. Acta Neuropathol. 2023;145:515-540. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 90. | Liu X, Chen C, Jiang Y, Wan M, Jiao B, Liao X, Rao S, Hong C, Yang Q, Zhu Y, Liu Q, Luo Z, Duan R, Wang Y, Tan Y, Cao J, Liu Z, Wang Z, Xie H, Shen L. Brain-derived extracellular vesicles promote bone-fat imbalance in Alzheimer's disease. Int J Biol Sci. 2023;19:2409-2427. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 38] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 91. | Krylova SV, Feng D. The Machinery of Exosomes: Biogenesis, Release, and Uptake. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:1337. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 415] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 92. | Xue T, Liu W, Wang L, Shi Y, Hu Y, Yang J, Li G, Huang H, Cui D. Extracellular vesicle biomarkers for complement dysfunction in schizophrenia. Brain. 2024;147:1075-1086. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 13.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 93. | Liu S, Zhang F, Wang X, Shugart YY, Zhao Y, Li X, Liu Z, Sun N, Yang C, Zhang K, Yue W, Yu X, Xu Y. Diagnostic value of blood-derived microRNAs for schizophrenia: results of a meta-analysis and validation. Sci Rep. 2017;7:15328. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 55] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 94. | Du Y, Yu Y, Hu Y, Li XW, Wei ZX, Pan RY, Li XS, Zheng GE, Qin XY, Liu QS, Cheng Y. Genome-Wide, Integrative Analysis Implicates Exosome-Derived MicroRNA Dysregulation in Schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2019;45:1257-1266. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 18.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 95. | Mobarrez F, Nybom R, Johansson V, Hultman CM, Wallén H, Landén M, Wetterberg L. Microparticles and microscopic structures in three fractions of fresh cerebrospinal fluid in schizophrenia: case report of twins. Schizophr Res. 2013;143:192-197. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 1.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 96. | Qian Y, Song J, Ouyang Y, Han Q, Chen W, Zhao X, Xie Y, Chen Y, Yuan W, Fan C. Advances in Roles of miR-132 in the Nervous System. Front Pharmacol. 2017;8:770. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 58] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 12.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 97. | Khoodoruth MAS, Khoodoruth WNC, Uroos M, Al-Abdulla M, Khan YS, Mohammad F. Diagnostic and mechanistic roles of MicroRNAs in neurodevelopmental & neurodegenerative disorders. Neurobiol Dis. 2024;202:106717. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 98. | Gruzdev SK, Yakovlev AA, Druzhkova TA, Guekht AB, Gulyaeva NV. The Missing Link: How Exosomes and miRNAs can Help in Bridging Psychiatry and Molecular Biology in the Context of Depression, Bipolar Disorder and Schizophrenia. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2019;39:729-750. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 55] [Cited by in RCA: 58] [Article Influence: 8.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 99. | Mu C, Gao M, Xu W, Sun X, Chen T, Xu H, Qiu H. Mechanisms of microRNA-132 in central neurodegenerative diseases: A comprehensive review. Biomed Pharmacother. 2024;170:116029. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 100. | Miller BH, Zeier Z, Xi L, Lanz TA, Deng S, Strathmann J, Willoughby D, Kenny PJ, Elsworth JD, Lawrence MS, Roth RH, Edbauer D, Kleiman RJ, Wahlestedt C. MicroRNA-132 dysregulation in schizophrenia has implications for both neurodevelopment and adult brain function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:3125-3130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 215] [Cited by in RCA: 254] [Article Influence: 18.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 101. | Zakutansky PM, Feng Y. The Long Non-Coding RNA GOMAFU in Schizophrenia: Function, Disease Risk, and Beyond. Cells. 2022;11:1949. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 102. | Yu X, Fan Z, Yang T, Li H, Shi Y, Ye L, Huang R. Plasma circRNA HIPK2 as a putative biomarker for the diagnosis and prediction of therapeutic effects in major depressive disorder. Clin Chim Acta. 2024;552:117694. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 103. | Bao H, Yan J, Huang J, Deng W, Zhang C, Liu C, Huang A, Zhang Q, Xiong Y, Wang Q, Wu H, Hou L. Activation of endogenous retrovirus triggers microglial immuno-inflammation and contributes to negative emotional behaviors in mice with chronic stress. J Neuroinflammation. 2023;20:37. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 104. | Payandeh Z, Tangruksa B, Synnergren J, Heydarkhan-Hagvall S, Nordin JZ, Andaloussi SE, Borén J, Wiseman J, Bohlooly-Y M, Lindfors L, Valadi H. Extracellular vesicles transport RNA between cells: Unraveling their dual role in diagnostics and therapeutics. Mol Aspects Med. 2024;99:101302. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 105. | Roest HP, IJzermans JNM, van der Laan LJW. Evaluation of RNA isolation methods for microRNA quantification in a range of clinical biofluids. BMC Biotechnol. 2021;21:48. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 15] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 106. | Ljungström M, Oltra E. Methods for Extracellular Vesicle Isolation: Relevance for Encapsulated miRNAs in Disease Diagnosis and Treatment. Genes (Basel). 2025;16:330. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 107. | Liu Y, Fu X, Tang Z, Li C, Xu Y, Zhang F, Zhou D, Zhu C. Altered expression of the CSMD1 gene in the peripheral blood of schizophrenia patients. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19:113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 3.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 108. | Teng P, Li Y, Ku L, Wang F, Goldsmith DR, Wen Z, Yao B, Feng Y. The human lncRNA GOMAFU suppresses neuronal interferon response pathways affected in neuropsychiatric diseases. Brain Behav Immun. 2023;112:175-187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 109. | Mahmoudi E, Green MJ, Cairns MJ. Dysregulation of circRNA expression in the peripheral blood of individuals with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. J Mol Med (Berl). 2021;99:981-991. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 110. | Huang X, Wang H, Wang C, Cao Z. The Applications and Potentials of Extracellular Vesicles from Different Cell Sources in Periodontal Regeneration. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:5790. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 4.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 111. | Wei ZX, Xie GJ, Mao X, Zou XP, Liao YJ, Liu QS, Wang H, Cheng Y. Exosomes from patients with major depression cause depressive-like behaviors in mice with involvement of miR-139-5p-regulated neurogenesis. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2020;45:1050-1058. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 65] [Cited by in RCA: 185] [Article Influence: 30.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 112. | Ran LY, Kong YT, Xiang JJ, Zeng Q, Zhang CY, Shi L, Qiu HT, Liu C, Wu LL, Li YL, Chen JM, Ai M, Wang W, Kuang L. Serum extracellular vesicle microRNA dysregulation and childhood trauma in adolescents with major depressive disorder. Bosn J Basic Med Sci. 2022;22:959-971. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 8] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 113. | Burrows K, Figueroa-Hall LK, Stewart JL, Alarbi AM, Kuplicki R, Hannafon BN, Tan C, Risbrough VB, McKinney BA, Ramesh R, Victor TA, Aupperle R, Savitz J, Teague TK, Khalsa SS, Paulus MP. Exploring the role of neuronal-enriched extracellular vesicle miR-93 and interoception in major depressive disorder. Transl Psychiatry. 2024;14:199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 11] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 5.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 114. | Liu Z, Li X, Sun N, Xu Y, Meng Y, Yang C, Wang Y, Zhang K. Microarray profiling and co-expression network analysis of circulating lncRNAs and mRNAs associated with major depressive disorder. PLoS One. 2014;9:e93388. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 115. | Cui X, Sun X, Niu W, Kong L, He M, Zhong A, Chen S, Jiang K, Zhang L, Cheng Z. Long Non-Coding RNA: Potential Diagnostic and Therapeutic Biomarker for Major Depressive Disorder. Med Sci Monit. 2016;22:5240-5248. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 39] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 6.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 116. | Yrondi A, Fiori LM, Nogovitsyn N, Hassel S, Théroux JF, Aouabed Z, Frey BN, Lam RW, Milev R, Müller DJ, Foster JA, Soares C, Rotzinger S, Strother SC, MacQueen GM, Arnott SR, Davis AD, Zamyadi M, Harris J, Kennedy SH, Turecki G. Association between the expression of lncRNA BASP-AS1 and volume of right hippocampal tail moderated by episode duration in major depressive disorder: a CAN-BIND 1 report. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11:469. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 117. | Cui X, Niu W, Kong L, He M, Jiang K, Chen S, Zhong A, Li W, Lu J, Zhang L. hsa_circRNA_103636: potential novel diagnostic and therapeutic biomarker in Major depressive disorder. Biomark Med. 2016;10:943-952. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 85] [Cited by in RCA: 108] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 118. | Bu T, Qiao Z, Wang W, Yang X, Zhou J, Chen L, Yang J, Xu J, Ji Y, Wang Y, Zhang W, Yang Y, Qiu X, Yu Y. Diagnostic Biomarker Hsa_circ_0126218 and Functioning Prediction in Peripheral Blood Monocular Cells of Female Patients With Major Depressive Disorder. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:651803. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 2.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 119. | Fiorentino A, O'Brien NL, Sharp SI, Curtis D, Bass NJ, McQuillin A. Genetic variation in the miR-708 gene and its binding targets in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2016;18:650-656. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 1.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 120. | Mola-Ali-Nejad R, Fakharianzadeh S, Maloum Z, Taheri M, Shirvani-Farsani Z. A gene expression analysis of long non-coding RNAs NKILA and PACER as well as their target genes, NF-κB and cox-2 in bipolar disorder patients. Nucleosides Nucleotides Nucleic Acids. 2023;42:527-537. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 121. | Lin R, Lopez JP, Cruceanu C, Pierotti C, Fiori LM, Squassina A, Chillotti C, Dieterich C, Mellios N, Turecki G. Circular RNA circCCNT2 is upregulated in the anterior cingulate cortex of individuals with bipolar disorder. Transl Psychiatry. 2021;11:629. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 122. | Hosseini M, Mokhtari MJ. Up-regulation of HOXA-AS2 and MEG3 long non-coding RNAs acts as a potential peripheral biomarker for bipolar disorder. J Cell Mol Med. 2024;28:e70150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 123. | Zamani B, Mehrab Mohseni M, Naghavi Gargari B, Taheri M, Sayad A, Shirvani-Farsani Z. Reduction of GAS5 and FOXD3-AS1 long non-coding RNAs in patients with bipolar disorder. Sci Rep. 2023;13:13870. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/