Published online Feb 19, 2026. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v16.i2.112054

Revised: August 26, 2025

Accepted: November 12, 2025

Published online: February 19, 2026

Processing time: 191 Days and 23 Hours

Depression is a prevalent global mental health disorder affecting over 300 million individuals, with studies indicating a 34% rise in cases from 2001 to 2020. In China, depression accounts for 3.0% of psychiatric disorders among adolescents, severely impairing patients’ quality of life. Despite pharmacological efficacy in acute-phase treatment, post-discharge relapse rates remain high (50% within one year), highlighting the need for effective continuity-of-care interventions. Tradi

To explore the application of the “Internet+” concept in post-discharge continuity of care for patients with mild to moderate depression.

From January 2024 to December 2024, 82 patients with mild and moderate depression who met the discharge criteria were selected as participants and randomly divided into an observation group and a control group (n = 41 each). The control group received conventional continuity care, while the observation group was provided with an integrated “Internet+”-based extended nursing model in addition to standard care. Both groups underwent a comprehensive three-month intervention program. Comparative assessments were conducted between the two groups regarding anxiety and depression levels, cognitive function, medication adherence, satisfaction rates, quality of life, and nursing staff’s professional identity.

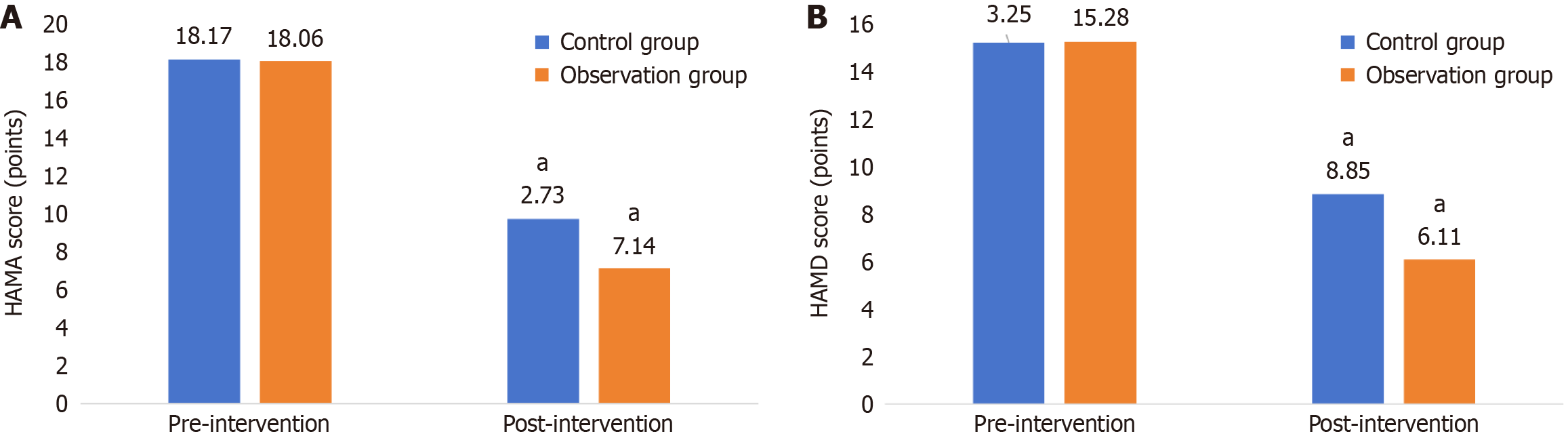

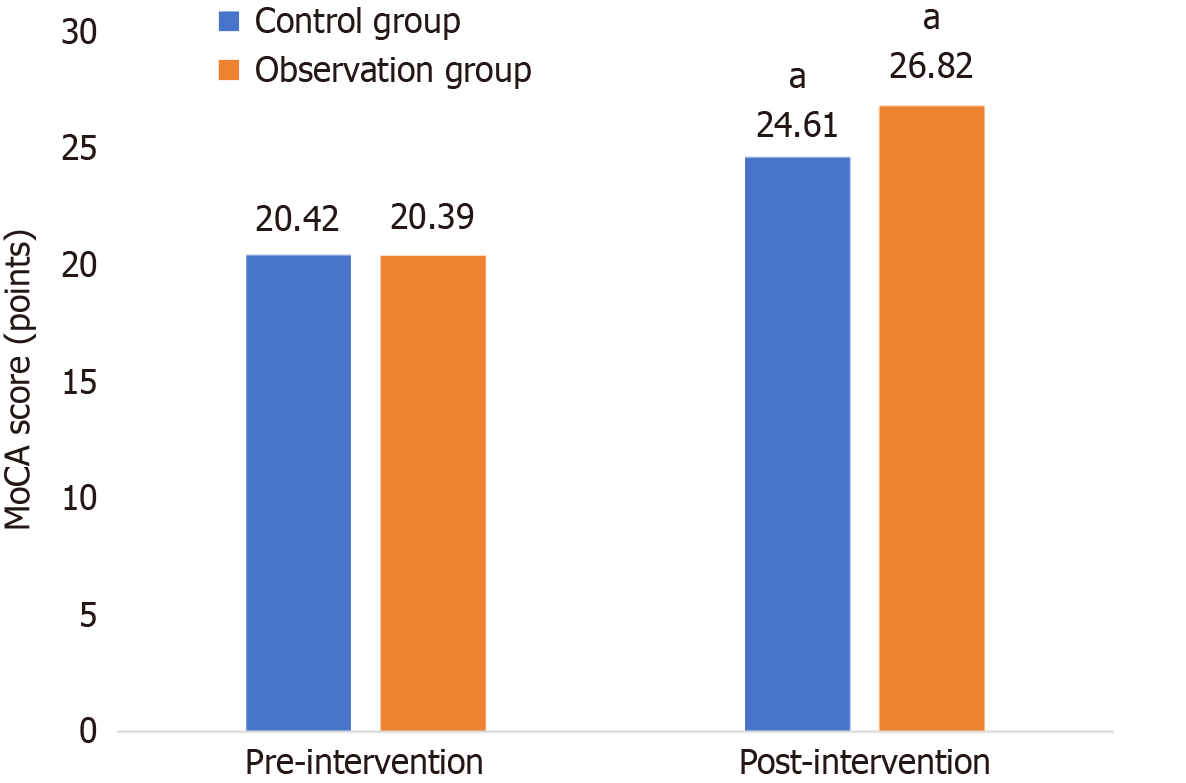

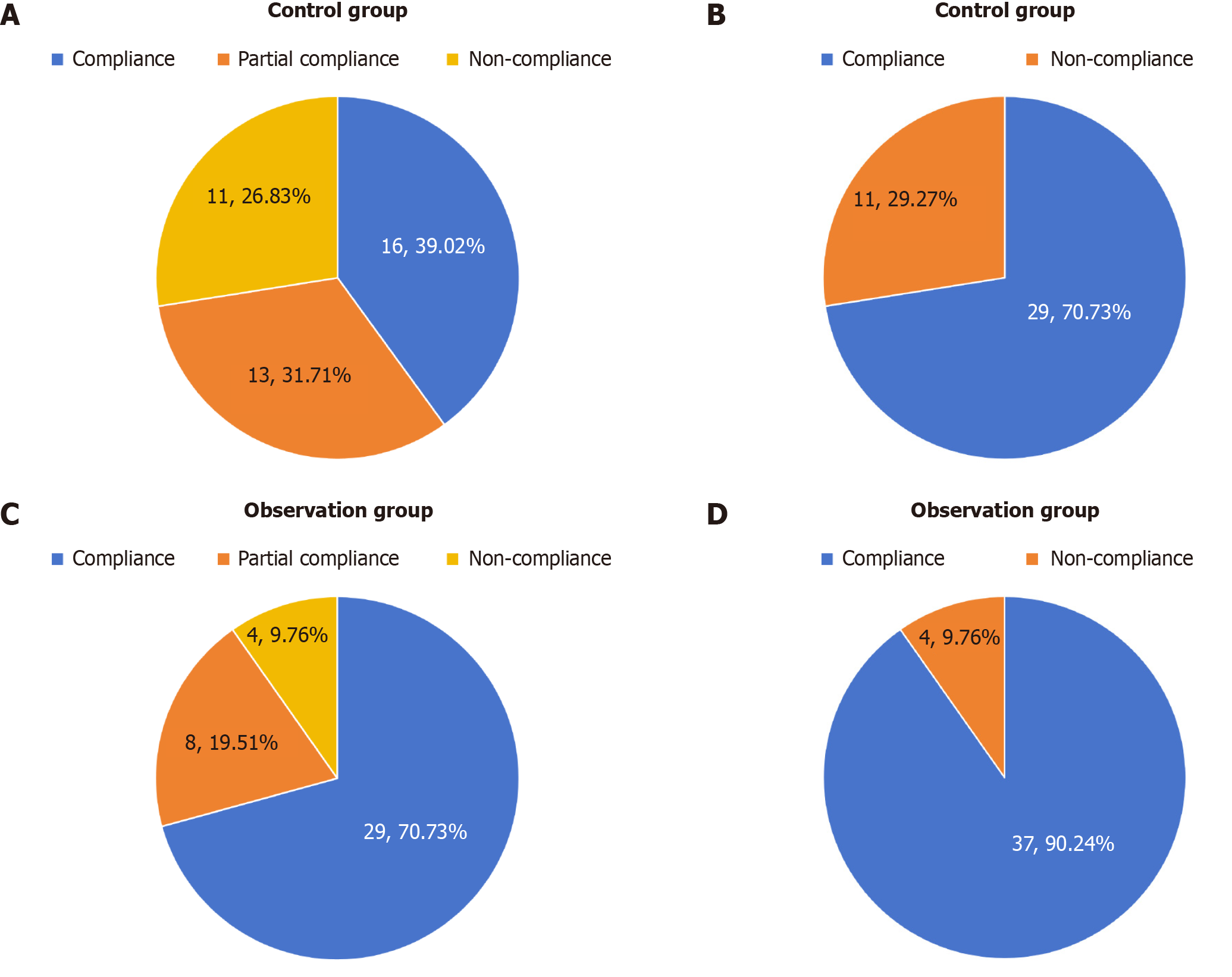

After the intervention, the observation group demonstrated significantly superior outcomes compared to the control group (P < 0.05 for all). Specifically, they exhibited lower scores on the Hamilton Anxiety Scale (7.14 ± 3.08) and Hamilton Depression Scale (6.11 ± 1.05), along with a higher score on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment Scale (26.82 ± 1.53). Medication compliance was also significantly higher in the observation group (90.24%) than in the control group (70.73%) (P < 0.05). Furthermore, patient satisfaction ratings across all surveyed domains—including overall satisfaction, the service effect of nursing staff, professional knowledge and skills, communication and listening abilities, time management and punctuality, friendliness and care, privacy protection, and the rationality of nursing service costs were significantly elevated in the observation group. After the intervention, both groups improved. Quality of life assessments revealed significantly better scores in the observation group across all dimensions: Physical function (51.31 ± 5.49), psychological function (44.49 ± 5.85), social function (43.62 ± 4.91), material life (46.21 ± 5.56), subjective perception of quality of life (3.57 ± 0.66), subjective perception of health status (3.57 ± 0.68), and total score (146.21 ± 12.37). Finally, the score of professional identity in the observation group was 28.49 ± 4.62, which was significantly higher than that of the control group (P < 0.05). And the professional identity of nurses in the observation group after the intervention was negatively correlated with anxiety and depression (P < 0.05), and positively correlated with cognition and medication compliance (P < 0.05).

“Internet+” continuous nursing can effectively improve the anxiety and depressive symptoms and cognitive function of patients with mild to moderate depression, improve their medication compliance, quality of life, and nursing satisfaction, and enhance the professional identity of nurses, which is worthy of clinical promotion and application.

Core Tip: This study investigates the impact of an “Internet+”-based extended care model on patients with mild to moderate depression following hospital discharge. It demonstrates that integrating Internet-based real-time supervision, reminders, and education significantly reduces anxiety and depressive symptoms (measured by Hamilton Anxiety Scale and Hamilton Depression Scale scores), enhances cognitive function (Montreal Cognitive Assessment Scale scores), and improves medication adherence and quality of life compared to traditional care methods. Furthermore, this innovative approach boosts patient satisfaction and strengthens nursing staff’s professional identity, highlighting its potential as a scalable intervention for post-hospital treatment of depression.

- Citation: Lin PP, Lv WW, Chen CM. Internet plus-based post-discharge continuity care for mild-to-moderate depression: An exploratory study. World J Psychiatry 2026; 16(2): 112054

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v16/i2/112054.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v16.i2.112054

Depression is a common mental disorder that now affects more than 300 million people[1], and in a meta-analysis[2] it was shown that from 2001 to 2020, the number of people with depression has elevated to 34%. China’s Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Epidemiological Survey showed that depression accounted for up to 3.0% of psychiatric disorders affecting adolescents, which seriously affects the quality of patients’ survival[3]. Despite the significant efficacy of medication in the acute phase of depression, it has a high relapse rate after discharge, and a study showed that the relapse rate of depression was as high as 50% 1 year after discharge[4]. Therefore, it is important to find effective intervention methods for the care of depressed patients after discharge. The traditional continuity of care model relies mainly on regular outpatient follow-up and one-way telephone follow-up, which is inefficient due to its difficulty in detecting dynamic fluctuations in depression symptoms through outpatient follow-up and the lack of a standardized assessment tool for one-way telephone follow-up. Consequently, healthcare professionals are often unable to respond in a timely manner to changes in the patient’s condition. In the study of Lee et al[5], it was shown that 26.4% of patients showed a decrease in medication adherence one month after discharge, thus affecting the efficacy of treatment. “Internet+” extended care is a new type of care with out-of-hospital real-time supervision, reminders, and education, which can significantly improve the outcome of patients with depression[6]. In a network meta-analysis[7], Internet-based cognitive behavioural therapy for depression significantly improved medication adherence in depressed patients (76% vs 54%), suggesting the feasibility of “Internet+”-based post-hospital extended care interventions for improving the outcomes of depressed patients. However, few studies have been conducted on the “Internet+”-based continuity of care model after hospital discharge. Based on the concept of “Internet+”, this study explores the therapeutic effect of post-hospital extended care intervention on patients with mild to moderate depression, and provides a scalable intervention programme for post-hospital diagnosis and treatment of depression.

A total of 82 patients with mild to moderate depression who met the discharge criteria of a tertiary B mental health speciality hospital in Wenzhou and participated in the post-hospital extended care service between January 2024 and December 2024 were selected as the participating subjects. The participants were evenly divided into an observation group and a control group (n = 41 each) using the random number table method. In the observation group, there were 13 males and 28 females; the age range was 23-49 years, with a mean age of (32.59 ± 6.12) years; the disease duration ranged from 3 to 16 months, with a mean of (7.82 ± 3.18) months; the duration of education ranged from 9 years to 20 years, with a mean of (15.42 ± 3.24) years; and 2 cases had underlying diseases such as hypertension. In the control group, there were 12 males and 29 females; the age range was 24-48 years, with a mean age of (32.65 ± 6.21) years; the disease duration ranged from 3 months to 17 months, with a mean of (7.87 ± 3.23) months; the duration of education ranged from 9 years to 21 years, with a mean of (15.46 ± 3.27) years; and 3 cases had underlying diseases such as hypertension. The baseline data of the two groups were comparable (P > 0.05). The present study was conducted on the basis of the ethical review criteria in the Declaration of Helsinki[8].

Inclusion criteria: (1) Meeting the clinical diagnostic criteria for depression[9]; (2) Age of 18-65 years old; (3) First depressive episode, no past medical history, and having completed acute inpatient treatment or outpatient standardized treatment, with fluctuations in Hamilton Depression Scale (HAMD) scores of ≤ 20%; (4) HAMD[10] score of 8-23 points at the screening visit; (5) Compliance with the principle of informed consent; and (6) Being able to use smartphone or tablet computer proficiently for Internet-based interventions.

Exclusion criteria: (1) No stable Internet access at the place of residence; (2) Previous respiratory disease; (3) Being a pregnant woman or in the breastfeeding period; (4) Presence of cognitive impairment with an Mini-Mental State Examination score of < 24; (5) Those who withdrew from the study or withdrew their informed consent in the middle of the study; and (6) Definite suicide attempts or suicidal thoughts within the last 1 month.

Sample size calculation: Forty-one cases/group were finally included according to the sample size calculation formula[11], setting α = 0.05 and β = 0.2, and considering a 20% dropout rate.

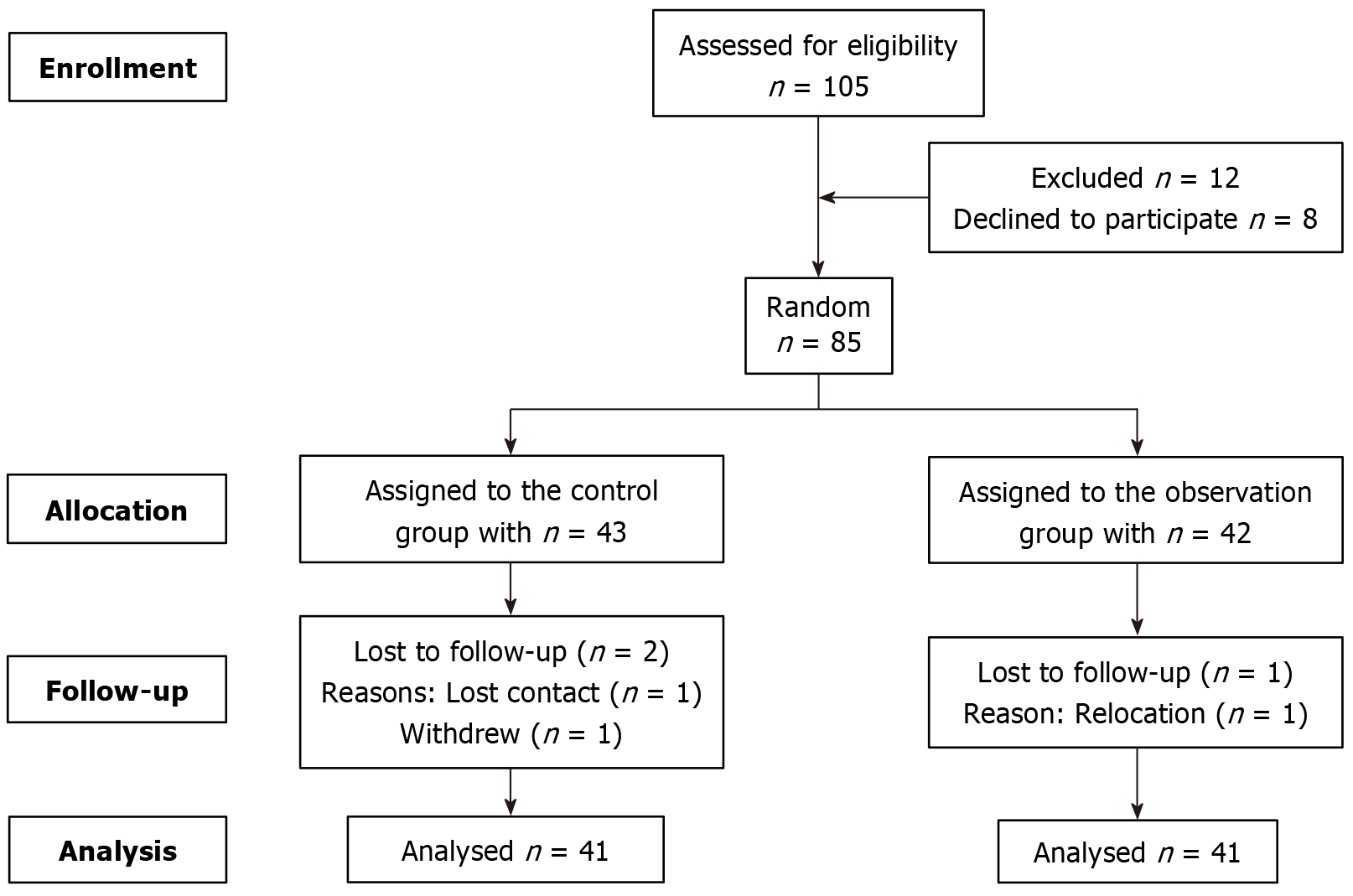

This study strictly adhered to the CONSORT guidelines. A total of 105 patients with mild to moderate depression who met the discharge criteria between January 2024 and December 2024 were screened. After excluding 12 individuals who did not meet the inclusion criteria and 8 who declined to participate, 85 were ultimately enrolled. Using the random number table method, they were allocated into an observation group (n = 42) and a control group (n = 43). During the intervention period, 2 participants dropped out from the control group (1 lost to follow-up and 1 withdrew), and 1 participant dropped out from the observation group (due to relocation). Ultimately, 82 patients completed the entire intervention and assessment process (41 in the observation group and 41 in the control group) and were included in the final data analysis. The detailed flow is shown in Figure 1.

Control group: Patients in the control group received routine continuity care, which included the following components: (1) Medication management: Patients were instructed to take their medications as prescribed, encouraged to set alarms for timely dosing, and family members were engaged to assist with supervision and accompaniment; (2) Lifestyle guidance: This involved dietary adjustments to increase intake of vitamins, protein, and dietary fiber while limiting spicy and greasy foods. Patients were also advised to maintain moderate physical activity and a regular sleep schedule for relaxation; and (3) Emotional monitoring & follow-up: Family members were asked to closely observe patients' emotional changes and report any abnormalities promptly. A dynamic follow-up system was established via telephone and WeChat, with weekly follow-ups in the first month, bi-weekly in the second month, and monthly from the third month onward.

The observation group: On the basis of routine care in the control group, the extended care intervention based on “Internet+” was implemented[12]. WeChat was chosen as the Internet platform to provide remote care and support ser

A multidisciplinary depression continuity care team was established to implement multidimensional joint inter

Online communication channels were established between healthcare providers and patients to ensure equitable access to intervention resources for all patients, prevent “digital exclusion”, and enhance patients’ willingness to actively participate and their ability to initiate behaviors. Within 24 hours before patients were discharged from the hospital, two nurse practitioners provided one-on-one guidance to patients and their families to help them bind the WeChat intervention group, to ensure that they can master the functions of viewing the pushed content, using the ‘quick question’ button, participating in the group’s exchanges, and so on.

Health education content and push plans were designed to enhance information absorption rate (especially for understanding when feeling down), reduce treatment fear, increase tolerance, and transform knowledge into concrete actions, improving patients’ executive ability and strengthening their initiative in disease management, and promoting patients to seek medical treatment proactively. The team jointly developed health education content, which was reviewed by the psychosomatic medicine expert group and then delivered by the administrator in the form of text, voice, video, etc. every Monday, Wednesday, and Friday at 9:00 am: The first week focused on the pathogenesis of depression, clinical manifestations, the role and side effects of medication, the importance of standardised medication, and the risks of unauthorised adjustment of medication. And the nurse demonstrated how to deal with common medication side effects such as dizziness and dry mouth through a 3-minute short video; (2) Week 2 focused on psychological adjustment skills and emotion management methods, and the psychotherapist arranged a positive breathing training course for the patient through a guided audio recording and arranges for the rehabilitated patient to share his/her methods of coping with emotional lows; (3) Week 3 focused on guiding reasonable diet, scientific exercise, family and social support, and social activity participation recommendations. The rehabilitation therapist pushed the list of tryptophan-rich foods to the patients through the WeChat platform, recorded and shared the exercise tutorials of home relaxation exercise, yoga, aerobic exercise, and resistance training, and the patients were required to perform aerobic exercise, relaxation exercise, yoga, and resistance training twice a week. Patients recorded their exercise duration using smart wristbands or by uploading exercise videos, and submitted these records to the WeChat group for structured check-ins. Based on the reported data, rehabilitation therapists provide personalized feedback on a weekly basis. Completion of more than 50% of the recommended exercise tasks was considered high adherence. Charge nurses reviewed the daily check-in status, sent encouraging responses to those who have completed the tasks, and privately messaged those who have not to inquire about the reasons; and (4) Week 4 focused on the necessity of follow-up and early warning signals of recurrence. The psychiatrist pushed a list of early recurrence symptoms for the patients to self-assess, and based on the patients’ self-assessment, the psychiatrist arranged for the patients to share their methods of coping with emotional depression. The psychologist pushed the list of early relapse symptoms to the patients for self-assessment and sent one-to-one recommendations for follow-up consultation based on the results of the patients’ self-assessment scale; the management staff would generate a follow-up countdown timer through the WeChat app to remind the patients to have follow-up consultations in a timely manner. The above content was pushed on a monthly cycle to strengthen patients’ awareness.

Interaction and feedback management were implemented to establish a sense of security, prevent the accumulation of negative emotions, foster emotional connection, and enhance patients’ hope and self-efficacy: (1) Team members provided scheduled online coverage daily from 8:00 am to 22:00 pm. After 22:00 pm, an automated nighttime response template was activated to address patient inquiries, ensuring immediate basic reassurance and guidance. Any remaining questions were revisited and fully addressed after 8:00 am the following day; (2) A “Rehabilitation Experience Sharing Meeting” was held every Sunday from 15:00 pm to 15:30 pm to encourage rehabilitating patients to share their experiences, and the therapists would give them professional guidance. For patients who have not interacted with the team for more than 7 days, the nurse practitioner would send the patient a follow-up consultation suggestion on a one-on-one basis; and (3) For patients who have not interacted for more than 7 days, the nurse would conduct one-on-one communication, focusing on personalized care throughout the whole process, recording the feedback of patients in detail, and discussing with the team on a regular basis in order to optimize the intervention strategies.

Quality monitoring and improvement were conducted to optimize educational content and enhance the precision and adaptability of interventions. Patients read the pushed content and replied “mastered” or “need to be explained”, and the management staff summarized the feedback data every week. If more than 15% of the patients marked a certain content as “need to be further explained”, it would be published in the next week’s newsletter. If more than 15% of the patients marked a content as “needing further explanation”, a 20-minute live question-and-answer session was arranged in the group the following week to analyze the topic, and the improvement plan was discussed in the team meeting. The post-hospital continuity of care intervention lasted 3 months in both groups.

Adverse event monitoring: Before the intervention, patients were clearly informed on how to report emotional fluctuations or other discomfort caused by online communication. A feedback button embedded in the WeChat Mini Program was established to encourage timely reporting of issues. Nurses reviewed and recorded all negative feedback daily and performed crisis intervention when necessary.

Privacy protection measures: Encrypted communication protocols were used to ensure information security during transmission. Patients were explicitly informed of the privacy policy, which guaranteed that personal information would not be disclosed. All discussions within the WeChat group were anonymized to avoid the disclosure of patients’ identifiable information.

Anxiety and depression psychological assessment: The HAMD[10] and Hamilton Anxiety Scale (HAMA)[13] were used to assess the psychological state of the two groups of patients before and 3 months after the intervention, respectively, and the scales were based on a five-point scale of 0-4 points, with the following specific criteria: 0 points (asymptomatic), 1 point (mild), 2 points (moderate), 3 points (severe) , 4 points (extremely severe). Dynamic observation and recording were analyzed in conjunction with the actual performance of the patients. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of the scales were 0.937 and 0.919, respectively.

Cognitive function: The Montreal Cognitive Assessment Scale (MoCA)[14] was used to assess the cognitive function of the two groups of patients before and 3 months after the intervention, covering the levels of attention, executive function, memory, language, and so on. A total of 30 points were scored, and a score of 26 or more on the scale was indicative of normalcy, with the score being proportional to cognitive function (some studies have shown that a 23-point threshold is more accurate). The scale’s Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.818.

Adherence: At the conclusion of the intervention, a comparative analysis of medication adherence was conducted between the two patient groups. This analysis primarily utilized WeChat backend data to measure indicators such as weekly push notification open rates, interaction frequency, and the number of inquiries. Additionally, based on the patients’ actual medication-taking records, adherence was categorized into three distinct levels[15]: (1) Complete adherence (strict compliance with the medication prescribed by the doctor); (2) Partial adherence (compliance with the medication prescribed by the doctor for ≥ 80% of the time); and (3) Non-adherence (compliance with the medication prescribed by the doctor for < 80% of the time). Total medication adherence rate was calculated as (number of cases of full adherence + number of cases of partial adherence)/total number of cases × 100%.

Satisfaction: A hospital’s self-designed satisfaction questionnaire was used to assess the two groups of patients. The questionnaire contained eight dimensions: (1) Overall satisfaction with out-of-hospital care; (2) Effectiveness of nursing services; (3) Professional knowledge and skills of nursing staff; (4) Communication and listening skills; (5) Time management and punctuality; (6) Service attitudes and humanistic care; (7) Privacy protection measures; and (8) Reasonableness of service costs. Each dimension was rated on a 5-point Likert scale: 1 (very dissatisfied) to 5 (very satisfied). Total satisfaction was calculated as (very satisfied + satisfied) number of cases/total number of cases × 100%.

Quality of life: The 74-item Comprehensive Quality of Life Inventory was used to assess the quality of life of the two groups of patients before the intervention and 3 months after the intervention, respectively[16]. The scale contains six dimensions: (1) Physical health status; (2) Mental health status; (3) Social adaptation and interpersonal relationships; (4) Material living conditions; (5) Life satisfaction; and (6) Health self-assessment and perception. A Likert 5-point scale (1 = very dissatisfied, 5 = very satisfied) was used for each dimension entry, with a total score range of 80-370, with higher scores indicating better quality of life. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the scale in this study was tested to be 0.891 (0.874 for the original scale), indicating good reliability.

Occupational identity[17]: The Occupational Identity Scale for Nursing Staff was used to assess the occupational identity of nursing staff in both groups before and after the implementation of the intervention. The scale contains five dimensions: (1) Professional identity; (2) Management style; (3) Work environment and stress; (4) Compensation and benefits; and (5) Personal development and professional growth, for a total of 15 entries. Each entry was scored on a 3-level scale: Satisfied (3 points), basically satisfied (2 points), and dissatisfied (1 point), with a total score range of 15-45 points, with higher scores indicating a stronger sense of professional identity among nursing staff. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of the scale in this study was 0.86, with good reliability.

SPSS27.0 software was used for all statistical analyses. Measurement data were first tested for normality; those conforming to a normal distribution are expressed as the mean ± SD and were compared between the two groups by the independent samples t-test. Counting data are expressed as n (%), with intergroup comparisons made using the the χ2 test or the Fisher’s exact probability method, as appropriate. Correlation analysis was used to further validate the effectiveness and applicability of the “Internet+” extended care interventions. The difference was considered statistically significant at P < 0.05.

After the intervention, compared with the control group, the HAMA (7.14 ± 3.08) and HAMD (6.11 ± 1.05) scores of the observation group were significantly lower (P < 0.05) (Figure 2).

The cognitive situation of the two groups was comparable before the intervention (P > 0.05); after the intervention, MoCA score (26.82 ± 1.53) was significantly higher in the observation group compared to the control group (P < 0.05) (Figure 3).

After the intervention, the observation group showed a significantly higher medication adherence than the control group (P < 0.05). Specifically, the rates of full adherence, partial adherence, and overall adherence (full + partial) in the observation group were 70.73% (29/41), 19.51% (8/41), and 90.24% (37/41), respectively, compared to 39.02% (16/41), 31.71% (13/41), and 70.73% (29/41) in the control group (Figure 4).

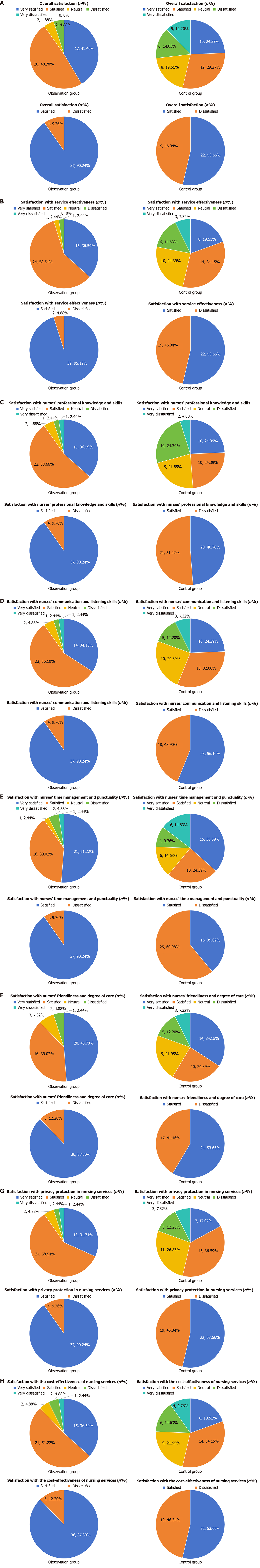

The observation group reported significantly higher satisfaction rates across all measured domains compared to the control group (P < 0.05). These included overall satisfaction (90.24%), effectiveness of nursing staff (95.12%), professional knowledge and skills (90.24%), communication and listening skills (90.24%), time management and punctuality (90.24%), friendliness and empathy (87.80%), protection of privacy (90.24%), and reasonableness of the cost of nursing services ( 87.80%) (Figure 5).

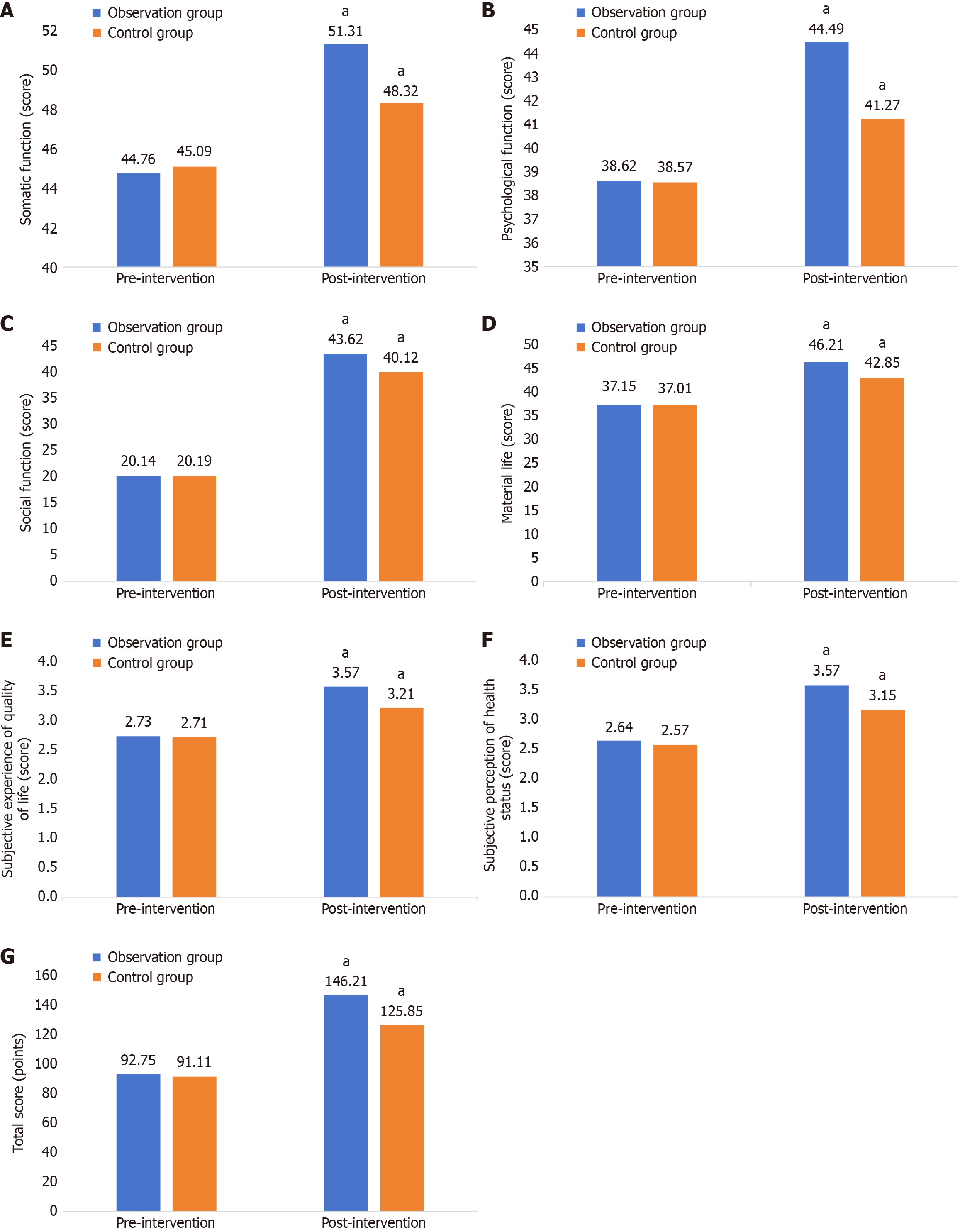

Before the intervention, the quality of life of the two groups was comparable (P > 0.05). After the intervention, the quality of life was improved in both groups, with the observation group having significantly higher scores of somatic function (51.31 ± 5.49), psychological function (44.49 ± 5.85), social function (43.62 ± 4.91), material life (46.21 ± 5.56), subjective perception of quality of life (3.57 ± 0.66), and subjective perception of health status (3.57 ± 0.68), as well as total score (146.21 ± 12.37) compared to the control group (P < 0.05) (Figure 6).

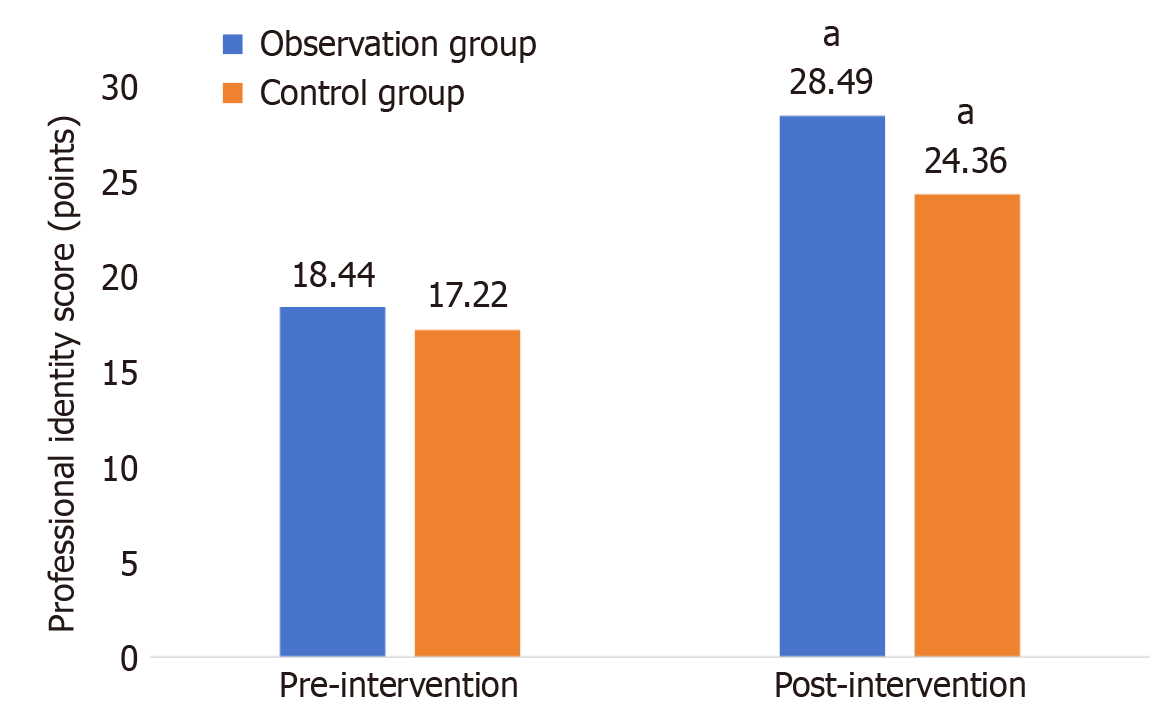

Before the intervention, the two groups were comparable in terms of professional identity (P > 0.05), but after the intervention, the observation group’s professional identity (28.49 ± 4.62) scores were significantly higher compared with those of the control group (P < 0.05) (Figure 7).

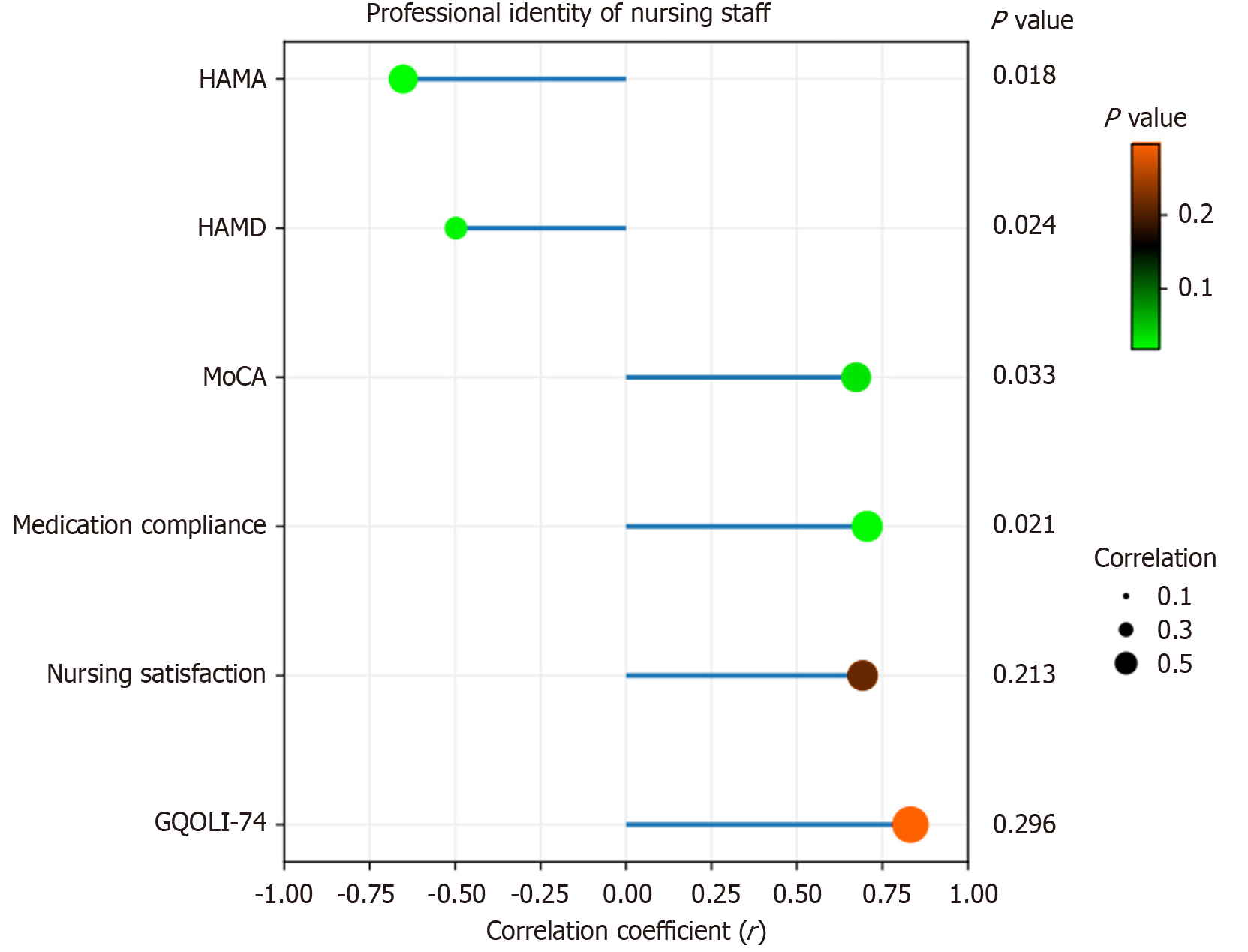

After the intervention, in the observation group, the professional identity of the nursing staff was negatively correlated with the anxiety and depression of the depressed patients (r = -0.70 and -0.53, respectively; P < 0.05), and positively correlated with their cognition, adherence to medication, satisfaction with nursing care, and quality of life (r = 0.72, 0.74, 0.73, and 0.81, respectively; P < 0.05) (Figure 8).

Depression is a common chronic disease characterized by high suicide and relapse rates. According to a review[18], 15%-20% of depressed patients die from suicide each year. Beutel et al[19] showed that the relapse rate in depressed patients was as high as 50% within two years after discharge from the hospital, which caused serious damage to patients and their families. Therefore, there is an urgent need to make use of the Internet platform to explore the establishment of a post-discharge care service led by psychiatric healthcare professionals to enhance the outcome of patients with depression.

This study shows that through the “Internet +” extended post-hospital care intervention, the HAMA and HAMD scores of the observation group were significantly lower than those of the control group three months after the intervention, and their adherence to medication (90.24%) was significantly improved compared to the control group (70.73%). This may be because: (1) The intervention leveraged short videos and interactive animations for health education and follow-up reminders. These materials broke down complex information, such as drug mechanisms and side effect management, to address the low retention rate associated with traditional verbal education. This approach helped reduce patients' cognitive biases regarding drug efficacy and enabled timely identification and response to side effects. Consequently, it enhanced their confidence in treatment, improved medication compliance, and indirectly reduced the incidence of self-discontinuation due to misunderstandings[20]; (2) Features such as the follow-up count

This study showed that after the intervention, the observation group had significantly higher scores of somatic function, psychological function, social function, material life, subjective perception of quality of life, subjective perception of health status, and total quality of life compared to the control group, indicating that the use of Internet-based post-hospital continued care had a significant effect in improving the overall quality of life. The possible reasons are as follows: Long-term depression inhibits the function of the prefrontal cortex and overactivates the amygdala, causing a lack of pleasure, which results in emotional regulation disorders[25] and gradually degrades the social skills of the patients, seriously disturbing the patients’ daily life and work, and leading to a significant decline in the quality of life; through the use of the Internet platform for post-hospital continuity of care interventions, the patients monitored their sleep status through the wearable devices and the sleep condition of the patients was monitored by the medical staff according to their specific conditions. Yoga exercises were tailored to their specific conditions, resulting in a significant reduction of 16% in their fatigue scale score[26]. Depressed patients could conduct virtual training of their daily social skills with psychologists through WeChat videos, thereby significantly improving their social avoidance behaviours; at the same time, the natural language processing function on the WeChat platform was able to identify negative semantics typed in by the patients in the late night, which triggered the AI cognitive-behavioural therapy and dialogue interventions, guiding the patients to develop their social skills through the use of artificial intelligence. Behavioural therapy and thus dialogue intervention guided patients’ expression and provided psychological support and coping strategies, thus helping patients alleviate their negative emotions, and ultimately improving their total quality of life score by 58%. In addition, this study showed that patient satisfaction in the observation group was significantly higher than that in the control group in terms of overall satisfaction with nursing care, the effectiveness of nursing staff’s services, professional knowledge and skills, communication and listening skills, time management and punctuality, friendliness and caring, privacy protection, and the reasonableness of the cost of nursing services, and the nurses in the observation group had a significantly higher sense of occupational identity (28.49 ± 4.62) than that of the control group, indicating that the nurses in the observation group performed more positively in terms of professional identity, which may be related to their higher satisfaction and professionalism. In Jiang et al[27]’s study, professional identity was shown to be a mediating variable between nurses work readiness and work performance (β = 0.113, P < 0.01), which is similar to the results of the present study, and further proves the importance of high-quality nursing care in enhancing nurses importance of professional identity.

Ma et al[28] pointed out in their study that nurses job performance and satisfaction were both positively correlated with their positive emotions, and that job satisfaction played a partial mediating role between positive emotions and job performance, with an effect value of 0.10, which accounted for 22.22% of the total effect, suggesting that there is a close relationship between nurses’ job performance and their professional identity. Further research in this study showed that nurses’ professional identity was negatively correlated with patients’ anxiety and depression scores, and positively correlated with their cognitive function, medication adherence, nursing satisfaction, and quality of life, suggesting that the use of the Internet to intervene in post-hospital continuity of care can enhance nurses’ professional identity, thereby improving the quality of care and overall experience of patients. This may be because: With the support of the Internet platform, the report of difficult points in refractory depression care was automatically generated through the intelligent medical record analysis system, and the patient’s recovery data were visualized, thus providing a structured competence enhancement pathway for the nursing staff and improving their nursing competence by 75.8%[29]; at the same time, the Internet platform provided real-time satisfaction evaluation and sharing of the recovery progress, so that the nursing staff’s work results are quantitatively presented. When data such as patients’ cognitive function improvement and medication adherence enhancement are visually displayed, the value recognition obtained by nursing staff can enhance their work engagement by 34.3%[30], and improve the recognition of patients and their families, thus enhancing nurses sense of professional efficacy and providing patients with better quality nursing services.

During the study period, a total of five patients reported emotional fluctuations caused by online communication, and all received timely psychological support. Moreover, no privacy information leakage incidents occurred, indicating that this intervention model has a relatively high level of security. In addition, although the “Internet +”-based continuous care in this study has improved the clinical efficacy, it has also increased the time investment of medical staff. According to the team’s records, each patient consumes an average of about 15 minutes of nursing resources per week (including answering questions, providing feedback, and organizing data), and 82 patients need to invest approximately 20.5 hours per month. However, this investment can reduce the number of follow-up visits and the emergency visit rate (this study shows that follow-up visit compliance increases by 28%), decrease the risk of recurrence (early warning recognition rate > 90%), and improve the quality of life of patients. From the perspective of health economics, if this model can reduce one hospitalization or emergency incident, the cost savings (such as follow-up expenses) can cover several months of platform maintenance costs, human resource input, and training costs.

In conclusion, post-hospital extended care based on “Internet+” can effectively improve the anxiety and depressive symptoms and cognitive function of patients with mild-to-moderate depression, improve their medication adherence, quality of life, and nursing satisfaction, and enhance the professional identity of nursing staff, which is worthy of clinical promotion and application.

However, although this study shows that “Internet +”-based continuous care has significant advantages in improving the prognosis of patients, its application limitations still need to be noted. First, this model relies on patients having a certain level of digital literacy and a stable online environment. Therefore, its promotion in areas with scarce digital resources (such as rural areas or the elderly) may be limited. In the future, it is necessary to explore the integration of hybrid models such as telephone and home visits to enhance accessibility. Second, from a cost-benefit perspective, despite the initial need for investment in technical infrastructure and personnel training for Internet-based platforms, in the long run, they can reduce the frequency of outpatient follow-up visits and lower the recurrence rate, thereby alleviating the burden on the medical system. In this study, nursing staff efficiently managed patients through a structured platform, significantly improving their satisfaction and rehabilitation indicators. This suggests that the model possesses a favourable cost-time efficiency and holds value for broader clinical dissemination.

| 1. | Moschny N, Zindler T, Jahn K, Dorda M, Davenport CF, Wiehlmann L, Maier HB, Eberle F, Bleich S, Neyazi A, Frieling H. Novel candidate genes for ECT response prediction-a pilot study analyzing the DNA methylome of depressed patients receiving electroconvulsive therapy. Clin Epigenetics. 2020;12:114. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Shorey S, Ng ED, Wong CHJ. Global prevalence of depression and elevated depressive symptoms among adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Clin Psychol. 2022;61:287-305. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 788] [Article Influence: 157.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Li F, Cui Y, Li Y, Guo L, Ke X, Liu J, Luo X, Zheng Y, Leckman JF. Prevalence of mental disorders in school children and adolescents in China: diagnostic data from detailed clinical assessments of 17,524 individuals. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2022;63:34-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 63] [Cited by in RCA: 281] [Article Influence: 70.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Martínez-Amorós E, Cardoner N, Gálvez V, de Arriba-Arnau A, Soria V, Palao DJ, Menchón JM, Urretavizcaya M. Can the Addition of Maintenance Electroconvulsive Therapy to Pharmacotherapy Improve Relapse Prevention in Severe Major Depressive Disorder? A Randomized Controlled Trial. Brain Sci. 2021;11:1340. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lee Y, Lee MS, Jeong HG, Youn HC, Kim SH. Medication Adherence Using Electronic Monitoring in Severe Psychiatric Illness: 4 and 24 Weeks after Discharge. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2019;17:288-296. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Huang CJ, Han W, Huang CQ. Effect of Internet + continuous midwifery service model on psychological mood and pregnancy outcomes for women with high-risk pregnancies. World J Psychiatry. 2023;13:862-871. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Karyotaki E, Efthimiou O, Miguel C, Bermpohl FMG, Furukawa TA, Cuijpers P; Individual Patient Data Meta-Analyses for Depression (IPDMA-DE) Collaboration, Riper H, Patel V, Mira A, Gemmil AW, Yeung AS, Lange A, Williams AD, Mackinnon A, Geraedts A, van Straten A, Meyer B, Björkelund C, Knaevelsrud C, Beevers CG, Botella C, Strunk DR, Mohr DC, Ebert DD, Kessler D, Richards D, Littlewood E, Forsell E, Feng F, Wang F, Andersson G, Hadjistavropoulos H, Christensen H, Ezawa ID, Choi I, Rosso IM, Klein JP, Shumake J, Garcia-Campayo J, Milgrom J, Smith J, Montero-Marin J, Newby JM, Bretón-López J, Schneider J, Vernmark K, Bücker L, Sheeber LB, Warmerdam L, Farrer L, Heinrich M, Huibers MJH, Kivi M, Kraepelien M, Forand NR, Pugh N, Lindefors N, Lintvedt O, Zagorscak P, Carlbring P, Phillips R, Johansson R, Kessler RC, Brabyn S, Perini S, Rauch SL, Gilbody S, Moritz S, Berger T, Pop V, Kaldo V, Spek V, Forsell Y. Internet-Based Cognitive Behavioral Therapy for Depression: A Systematic Review and Individual Patient Data Network Meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry. 2021;78:361-371. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 359] [Cited by in RCA: 529] [Article Influence: 105.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Goodyear MD, Krleza-Jeric K, Lemmens T. The Declaration of Helsinki. BMJ. 2007;335:624-625. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 233] [Cited by in RCA: 511] [Article Influence: 26.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Schneider W, Freyberger HJ, Muhs A. [10th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-10)--possibilities and limits for psychodynamically orientated diagnosis]. Psychother Psychosom Med Psychol. 1995;45:253-260. [PubMed] |

| 10. | HAMILTON M. A rating scale for depression. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1960;23:56-62. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21041] [Cited by in RCA: 23390] [Article Influence: 354.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 11. | Bacchetti P, Leung JM. Sample size calculations in clinical research. Anesthesiology. 2002;97:1028-9; author reply 1029. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 20] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Alneyadi M, Drissi N, Almeqbaali M, Ouhbi S. Biofeedback-Based Connected Mental Health Interventions for Anxiety: Systematic Literature Review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth. 2021;9:e26038. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 34] [Article Influence: 6.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Beck AT, Steer RA. Relationship between the beck anxiety inventory and the Hamilton anxiety rating scale with anxious outpatients. J Anxiety Disord. 1991;5:213-223. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 14. | de Guise E, Leblanc J, Champoux MC, Couturier C, Alturki AY, Lamoureux J, Desjardins M, Marcoux J, Maleki M, Feyz M. The mini-mental state examination and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment after traumatic brain injury: an early predictive study. Brain Inj. 2013;27:1428-1434. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 30] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Navarro V. Improving medication compliance in patients with depression: Use of orodispersible tablets. Adv Ther. 2010;27:785-795. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 21] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Shi B, Wang L, Huang S. Effect of high-quality nursing on psychological status and prognosis of patients undergoing brain tumor surgery. Am J Transl Res. 2021;13:11974-11980. [PubMed] |

| 17. | Li Z, Zuo Q, Cheng J, Zhou Y, Li Y, Zhu L, Jiang X. Coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic promotes the sense of professional identity among nurses. Nurs Outlook. 2021;69:389-398. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 23] [Cited by in RCA: 31] [Article Influence: 5.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Nierenberg AA, Agustini B, Köhler-Forsberg O, Cusin C, Katz D, Sylvia LG, Peters A, Berk M. Diagnosis and Treatment of Bipolar Disorder: A Review. JAMA. 2023;330:1370-1380. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 197] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Beutel M, Krakau L, Kaufhold J, Bahrke U, Grabhorn A, Hautzinger M, Fiedler G, Kallenbach-Kaminski L, Ernst M, Rüger B, Leuzinger-Bohleber M. Recovery from chronic depression and structural change: 5-year outcomes after psychoanalytic and cognitive-behavioural long-term treatments (LAC depression study). Clin Psychol Psychother. 2023;30:188-201. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Furukawa TA, Suganuma A, Ostinelli EG, Andersson G, Beevers CG, Shumake J, Berger T, Boele FW, Buntrock C, Carlbring P, Choi I, Christensen H, Mackinnon A, Dahne J, Huibers MJH, Ebert DD, Farrer L, Forand NR, Strunk DR, Ezawa ID, Forsell E, Kaldo V, Geraedts A, Gilbody S, Littlewood E, Brabyn S, Hadjistavropoulos HD, Schneider LH, Johansson R, Kenter R, Kivi M, Björkelund C, Kleiboer A, Riper H, Klein JP, Schröder J, Meyer B, Moritz S, Bücker L, Lintvedt O, Johansson P, Lundgren J, Milgrom J, Gemmill AW, Mohr DC, Montero-Marin J, Garcia-Campayo J, Nobis S, Zarski AC, O'Moore K, Williams AD, Newby JM, Perini S, Phillips R, Schneider J, Pots W, Pugh NE, Richards D, Rosso IM, Rauch SL, Sheeber LB, Smith J, Spek V, Pop VJ, Ünlü B, van Bastelaar KMP, van Luenen S, Garnefski N, Kraaij V, Vernmark K, Warmerdam L, van Straten A, Zagorscak P, Knaevelsrud C, Heinrich M, Miguel C, Cipriani A, Efthimiou O, Karyotaki E, Cuijpers P. Dismantling, optimising, and personalising internet cognitive behavioural therapy for depression: a systematic review and component network meta-analysis using individual participant data. Lancet Psychiatry. 2021;8:500-511. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 164] [Cited by in RCA: 141] [Article Influence: 28.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Meng P, Li C, Duan S, Ji S, Xu Y, Mao Y, Wang H, Tian J. Epigenetic Mechanism of 5-HT/NE/DA Triple Reuptake Inhibitor on Adult Depression Susceptibility in Early Stress Mice. Front Pharmacol. 2022;13:848251. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 10] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Del Pino-Sedeño T, González-Pacheco H, González de León B, Serrano-Pérez P, Acosta Artiles FJ, Valcarcel-Nazco C, Hurtado-Navarro I, Rodríguez Álvarez C, Trujillo-Martín MM; MAPDep Team. Effectiveness of interventions to improve adherence to antidepressant medication in patients with depressive disorders: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Front Public Health. 2024;12:1320159. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Edman S, Starck J, Corell L, Hangasjärvi W, von Finckenstein A, Reimeringer M, Reitzner S, Norrbom J, Moberg M, von Walden F. Exercise-induced plasma mature brain-derived neurotrophic factor elevation in children, adolescents and adults: influence of age, maturity and physical activity. J Physiol. 2025;603:2333-2347. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | de Oliveira LRS, Machado FSM, Rocha-Dias I, E Magalhães COD, De Sousa RAL, Cassilhas RC. An overview of the molecular and physiological antidepressant mechanisms of physical exercise in animal models of depression. Mol Biol Rep. 2022;49:4965-4975. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Ma F, Bian H, Jiao W, Zhang N. Single-cell RNA-seq reveals the role of YAP1 in prefrontal cortex microglia in depression. BMC Neurol. 2024;24:191. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Zhi WI, Baser RE, Zhi LM, Talukder D, Li QS, Paul T, Patterson C, Piulson L, Seluzicki C, Galantino ML, Bao T. Yoga for cancer survivors with chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy: Health-related quality of life outcomes. Cancer Med. 2021;10:5456-5465. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 4.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Jiang Z, Su Y, Meng R, Lu G, Liu J, Chen C. The effects of work readiness, organizational justice and professional identity on the work performance of new nurses: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Nurs. 2024;23:759. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Ma X, Wu D, Hou X. Positive affect and job performance in psychiatric nurses: A moderated mediation analysis. Nurs Open. 2023;10:3064-3074. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Henshall C, Davey Z, Srikesavan C, Hart L, Butcher D, Cipriani A. Implementation of a Web-Based Resilience Enhancement Training for Nurses: Pilot Randomized Controlled Trial. J Med Internet Res. 2023;25:e43771. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Jedwab RM, Hutchinson AM, Manias E, Calvo RA, Dobroff N, Glozier N, Redley B. Nurse Motivation, Engagement and Well-Being before an Electronic Medical Record System Implementation: A Mixed Methods Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:2726. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 24] [Article Influence: 4.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/