Published online Feb 19, 2026. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v16.i2.111799

Revised: August 7, 2025

Accepted: October 17, 2025

Published online: February 19, 2026

Processing time: 203 Days and 21.1 Hours

Schizophrenia is a debilitating psychiatric disorder marked by cognitive impair

To explore the association between frontal lobe EEG asymmetry and cognitive prognosis in patients with schizophrenia.

This retrospective study analyzed data from 104 patients with schizophrenia who received treatment between 2020 and 2023. The patients were divided into good (n = 52) and poor (n = 52) cognitive prognosis groups based on post-treatment scores on the Measurement and Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia Consensus Cognitive Battery. Frontal EEG asymmetry was asse

Notable differences in EEG asymmetry were observed under eyes-open condi

The findings suggest that eyes-open frontal EEG asymmetry and FPN connectivity are associated with cognitive prognosis in individuals with schizophrenia.

Core Tip: This study investigates the correlation between frontal lobe electroencephalogram asymmetry and cognitive prognosis in patients with schizophrenia. By focusing on frontal alpha asymmetry and frontoparietal network connectivity, we explore novel neurophysiological biomarkers for predicting cognitive outcomes. Our findings suggest that frontal alpha asymmetry under eyes-open conditions may serve as a critical indicator of cognitive recovery post-treatment. These insights could enhance personalized treatment plans and improve prognostic evaluations in clinical settings.

- Citation: Sang S, Wang F. Correlation of frontal lobe electroencephalogram asymmetry and cognitive prognosis in schizophrenia. World J Psychiatry 2026; 16(2): 111799

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v16/i2/111799.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v16.i2.111799

Schizophrenia is a severe psychiatric disorder characterized by a constellation of symptoms, including delusions, hallucinations, cognitive impairments, and negative affective states[1]. These symptoms impair an individual’s functional capacity and quality of life[2]. Among these, cognitive dysfunction has garnered increasing attention[3]. Cognitive deficits in schizophrenia are profound, affecting working memory, executive function, attention, and social cognition, and are considered critical determinants of functional outcomes[4]. However, the neurobiological mechanisms underlying these cognitive impairments remain inadequately understood, highlighting the need for further research[5].

Electroencephalography (EEG) offers a noninvasive method for examining brain activity and has been extensively used in research on neurophysiological changes in schizophrenia[6]. Among the EEG-derived metrics, frontal alpha asymmetry (FAA) has received growing attention. FAA reflects the distribution of alpha band power (8-12 Hz) between the right and left frontal cortices[7] and has traditionally been associated with affective processing, motivational states, and approach-avoidance behavior, particularly in clinical populations with mood disorders[8]. Emerging evidence sug

The frontal lobes, particularly the prefrontal cortex, play a critical role in cognitive functions, such as working memory, planning, decision-making, and social interactions[10]. Dysregulated activity in these regions has been implicated in diverse cognitive deficits observed in individuals with schizophrenia[11]. Current neurobiological models suggest that disrupted dopaminergic signaling, a core feature of schizophrenia pathophysiology, contributes to prefrontal cortex dysfunction, thereby exacerbating cognitive symptoms[12]. Asymmetries in EEG signals, which may reflect lateralized metabolic activity or dysfunction, can hold prognostic significance for cognitive recovery following schizophrenia trea

Despite these insights, the relationship between frontal EEG asymmetry and cognitive outcomes in schizophrenia remains relatively underexplored[14]. Such asymmetry may reflect compensatory neural mechanisms or disruptions in typical hemispheric functioning that are critical for various cognitive domains[15]. However, few studies have systematically examined how specific patterns of frontal asymmetry relate to cognitive prognoses in schizophrenia, particularly in the context of pharmacological interventions[16].

The conceptual framework guiding this study posits that frontal EEG asymmetry (FAA) reflects an imbalance in prefrontal metabolic activity between hemispheres, and disrupted frontoparietal network (FPN) connectivity signifies inefficiencies in frontoparietal information transfer. Collectively, these neural markers may limit cognitive plasticity during treatment. This model aligns with existing theories of dopaminergic dysfunction in schizophrenia and extends prior research on FAA in mood disorders by applying it to the context of cognitive prognosis[17].

This study aimed to investigate the association between frontal lobe EEG asymmetry and cognitive prognosis in patients with schizophrenia. The analysis focused on relative alpha power across several frontal regions, including the mid-frontal, lateral-frontal, anterior temporal, prefrontal, and medial prefrontal cortices, under both eyes-open and eyes-closed conditions. Through a comprehensive examination of these relationships, we sought to identify EEG-based biomarkers that may serve as indicators of cognitive prognosis in schizophrenia.

This study conducted a retrospective analysis of 104 patients diagnosed with schizophrenia who received treatment at Ningbo Psychiatric Hospital between January 2020 and December 2023. The objective was to assess cognitive prognosis one year after treatment using the Measurement and Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia Consensus Cognitive Battery (MCCB). Based on the median post-treatment MCCB scores, patients were classified into two groups: The good cognitive prognosis group (n = 52) and poor cognitive prognosis group (n = 52). The sample size (n = 104) was determined on the basis of prior studies reporting moderate effect sizes (Cohen’s d = 0.3-0.5) in FAA differences among schizophrenia subgroups. A post hoc power analysis indicated that the study had 80% power to detect significant FAA differences at α value of 0.05, assuming a standard deviation of 0.03.

Inclusion criteria: Participants were eligible for inclusion when they met the following criteria: (1) Age of 18 years or older; (2) Diagnosis of schizophrenia according to the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision criteria for schizophrenia; (3) Undisrupted adherence to prescribed medication regimens without interruption; (4) Right-handedness; (5) Complete clinical documentation; and (6) Availability for regular follow-up assessments.

Exclusion criteria: Participants were excluded from the study when they met any of the following conditions: (1) Presence of neurological disorders, such as cerebrovascular disease and epilepsy, and a history of brain injury resulting in coma; (2) Dependence on substances, including alcohol and heroin, or diagnosis of a personality disorder; (3) Pregnancy or breastfeeding; (4) Presence of serious physical illnesses, such as cardiac, hepatic, and renal failure, or any form of cancer; and (5) Inability to cooperate with EEG assessments.

Upon admission, all patients were enrolled in a standardized one-year treatment regimen. The specific antipsychotic medications administered varied across participants, guided by clinical judgment and individualized treatment needs. Initial assessments were conducted to evaluate medication tolerability prior to initiating long-term therapy. Owing to the retrospective design of the study, variability was present in both the types and dosages of antipsychotic medications. For instance, some patients received intramuscular injections of risperidone microspheres, while others were treated with oral formulations such as olanzapine or aripiprazole. Patients newly prescribed these medications underwent a short-term trial period for the assessment of tolerability before the continuation of the prescribed regimen. For each participant, the treatment regimen remained consistent throughout the study period. The inclusion criteria did not restrict the type of antipsychotic medication, as long as the same medication was administered continuously during the treatment period. This approach was designed to minimize potential confounding effects related to medication variability, thereby allowing us to focus on the primary research objective.

The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) was employed for the assessment of the severity of schizophrenia symptoms prior to treatment. The PANSS comprises 30 items divided into three subscales: Positive symptoms, negative symptoms, and general psychopathology. Each item is rated on a seven-point scale, ranging from 1 (absent) to 7 (extremely severe). The positive symptom subscale includes features, such as delusions and hallucinations, whereas the negative symptom subscale captures impairments, such as emotional blunting and social withdrawal. The general psychopathology subscale encompasses symptoms, including anxiety and depression. PANSS scores were derived from structured professional interviews and clinical observations conducted over the preceding week. Higher total and subscale scores reflect greater symptom severity, whereas lower scores indicate milder or absent symptoms.

Following one year of treatment, the MCCB was administered to evaluate patients’ cognitive function prognosis. The MCCB includes 10 subtests that assess seven key cognitive domains: (1) Speed of processing: Include the Brief Assessment of Cognition in Schizophrenia Symbol Coding and Trail Making Test A; (2) Attention/vigilance: Assessed by the Continuous Performance Test-Identical Pairs; (3) Working memory: Measured through the Wechsler Memory Scale-Third Edition Spatial Span and Letter-Number Span; (4) Verbal learning: Evaluated using the Hopkins Verbal Learning Test-Revised; (5) Visual learning: Assessed by the Brief Visuospatial Memory Test-Revised; (6) Reasoning and problem solving: Measured with the Neuropsychological Assessment Battery Mazes; and (7) Social cognition: Includes Managing Emotions and the Penn Emotion Recognition Test.

Raw scores from each subtest were converted into standardized scores and subsequently into T-scores with established normative conversion tables. These T-scores were then aggregated to generate a composite cognitive function score. Higher composite scores reflect better cognitive functioning. All the participants’ MCCB scores were computed, with individuals scoring above the median classified into the good cognitive prognosis group and those scoring below the median placed in the poor cognitive prognosis group.

EEG data were recorded using a Nihon Kohden EEG-1200C system (Nihon Kohden Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) while participants were seated comfortably in a sound-attenuated room. Recordings were performed using the system’s integrated amplifier and a standard headcap equipped with gold-cup electrodes arranged according to the international 10-20 system. EEG signals were recorded from 19 standard scalp locations. For ocular artifact monitoring, disposable electrodes were placed: Vertically above and below the left eye (vertical electrooculography), and horizontally at the outer canthi of both eyes (horizontal electrooculography). All signals were referenced to linked mastoids (A1/A2), with the ground electrode positioned on the forehead (FPz). Electrode impedance was maintained below 10 kΩ throughout the recording. Data was acquired at a sampling rate of 500 Hz with an analog bandpass filter of 0.5-120 Hz.

Resting-state EEG was recorded for five minutes under both eyes-open and eyes-closed conditions. Data preprocessing and analysis were performed using the system’s native NeuroWorkbench software (Nihon Kohden Corporation, Tokyo, Japan). Ocular artifacts (blinks/saccades) were corrected using built-in regression-based algorithms in NeuroWorkbench, triggered by vertical electrooculography excursions exceeding ± 80 μV. Continuous data were bandpass-filtered between 1.0-70.0 Hz (infinite impulse response Butterworth, zero-phase shift) and segmented into 2.0-second epochs. Epochs containing artifacts (amplitude > ± 100 μV or gradient > 50 μV/sample) were automatically rejected. Fast Fourier transform was applied to 30 randomly selected artifact-free epochs per participant/condition to compute absolute power across standard frequency bands: Delta (1-4 Hz), theta (4-8 Hz), alpha (8-13 Hz), beta (13-30 Hz), and gamma (30-70 Hz).

FAA was calculated using six homologous frontal electrode pairs: F4-F3, F8-F7, FP2-FP1, AF4-AF3, F6-F5, and F2-F1. These electrode pairs were selected based on established protocols in depression research, where FAA has been extensively examined. Particular emphasis was placed on mid-frontal (F4-F3) and lateral-frontal (F8-F7) sites, as these regions are considered reliable indicators of FAA associated with affective processing and depressive phenotypes. Additional electrode pairs (FP2-FP1, AF4-AF3, F6-F5, F2-F1) were included to enable a more comprehensive mapping of frontal subregions. Alpha-band power (8-13 Hz; PSα) was extracted, and FAA was computed as the difference in log10-transformed alpha power between right and left homologous sites: FAA = log10(PSαr) - log10(PSαl). More negative FAA values indicate relatively greater alpha power in the left hemisphere, reflecting reduced cortical activation (i.e., hypoactivation) in the left frontal region. The term “greater asymmetry” refers to deviations from zero (i.e., larger |FAA| values), with directionality (negative/positive) indexing lateralized activation patterns. Eyes-open and eyes-closed conditions were analyzed separately to account for state-dependent neural dynamics. Additional analyses of delta-band activity confirmed minimal residual ocular artifact, supporting the reliability of the alpha-band measures.

All magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) data were acquired on a united imaging uMR 586 3.0T scanner (United Imaging Healthcare, Shanghai, China) using the system’s 64-channel phased-array head-neck coil and native acquisition software (R001). Structural images were obtained with a three-dimensional magnetization-prepared rapid gradient echo sequence (echo time = 3.8 milliseconds, repetition time = 2000 milliseconds, inversion time = 990 milliseconds, field of view = 256 mm × 256 mm, acquisition matrix = 256 × 256, spatial resolution = 1.0 mm × 1.0 mm × 1.0 mm, 192 sagittal slices, GRAPPA acceleration factor = 2). Resting-state functional MRI data were collected using a single-shot gradient-echo echo-planar imaging pulse sequence (echo time = 30 milliseconds, repetition time = 2500 milliseconds, field of view = 220 mm × 220 mm, matrix = 64 × 64, voxel size = 3.44 mm × 3.44 mm × 4.0 mm, 35 axial slices, flip angle = 90°, bandwidth = 2232 Hz/Px, GRAPPA acceleration factor = 2). During the 8-minute resting-state functional MRI scan, participants maintained eyes-open fixation on a white cross centered on a black background.

Functional data preprocessing and analysis were performed using FSL 5.0.5 with uMR-specific B0 field correction based on system phase maps. Functional images underwent motion correction using MCFLIRT, geometric distortion correction (B0 unwarping), spatial smoothing with a 6 mm full width at half maximum Gaussian kernel, and high-pass temporal filtering (0.01-0.1 Hz). Structural-functional registration was achieved via boundary-based registration, followed by nonlinear normalization to MNI 152 standard space (FNIRT) with 3-mm isotropic resampling. To mitigate the potential confounding effects of head motion, strict motion exclusion criteria were applied: No participant exhibited head motion exceeding 1.5 mm in absolute mean displacement, in accordance with established thresholds in prior studies. The average head motion was 0.31 ± 0.08 mm in the healthy control group and 0.29 ± 0.07 mm in the schizophrenia group, with no statistically significant difference observed between the two groups.

Group-level Independent Component Analysis was conducted using the Multivariate Exploratory Linear Optimized Decomposition into Independent Components Version 3.14, with temporal concatenation applied across all participants. Bayesian dimensionality estimation identified 43 distinct spatiotemporal components. Template matching against FSL’s standard network templates confirmed the FPN components. Subject-specific spatial maps and time courses were derived via dual regression. From these data, mean connectivity values were extracted within gray matter-masked left and right FPNs. The laterality index (LI) of FPN connectivity was calculated using the following formula: LI = (left FPN - right FPN)/(left FPN + right FPN). Positive LI values indicate left-hemispheric dominance in FPN connectivity, whereas negative values indicate right-hemispheric dominance.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 29.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, United States). Categorical variables were presented as n (%) and analyzed using the χ2 test under appropriate conditions. Specifically, the standard χ2 test was applied when the total sample size was ≥ 40 and the expected frequency (T) in all cells was ≥ 5. When the sample size was ≥ 40 but the expected frequency in any cell ranged from 1 to < 5, a continuity-corrected χ2 test was used. For sample size of < 40 or when any expected frequency was < 1, Fisher’s exact test was employed to ensure statistical validity.

Continuous variables were assessed for normality using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Variables that followed a normal distribution were reported as mean ± SD, while non-normally distributed data were presented as medians and interquartile ranges [median (25th percentile, 75th percentile)] and analyzed using the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. A P value of < 0.05 was considered indicative of statistical significance. Correlation analyses were conducted using Pearson’s correlation for normally distributed continuous variables and Spearman’s correlation for ordinal or non-normally distributed variables.

The two groups demonstrated comparable demographic and clinical characteristics prior to treatment. The mean age was 38.56 ± 4.96 years in the good cognitive prognosis group and 37.97 ± 4.68 years in the poor prognosis group, with no significant difference observed (P = 0.5341; Table 1). Gender distribution was similar, with 29 females and 27 males in the good prognosis group and 27 females and 25 males in the poor prognosis group (P = 0.694). Body mass index did not differ significantly between groups (21.86 ± 2.65 kg/m2vs 21.93 ± 2.34 kg/m2; P = 0.873), nor did years of education (13.86 ± 1.42 years vs 13.75 ± 1.53 years; P = 0.691). Histories of smoking and alcohol use and the presence of comorbidities, such as hypertension, diabetes, and depression, showed no significant group differences. Marital status and ethnicity were similarly distributed. The duration of illness averaged 5.27 ± 1.52 years in the good prognosis group and 5.23 ± 1.49 years in the poor prognosis group (P = 0.894). Furthermore, baseline clinical symptom scores, including positive, negative, and general psychopathology subscales, did not differ significantly between groups. Overall, there were no statistically significant differences in demographic variables or pre-treatment clinical profiles between the two groups.

| Good cognitive prognosis group (n = 52) | Poor cognitive prognosis group (n = 52) | t/χ² | P value | |

| Age (years) | 38.56 ± 4.96 | 37.97 ± 4.68 | 0.624 | 0.5341 |

| Female/male | 29 | 27 | 0.155 | 0.694 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 21.86 ± 2.65 | 21.93 ± 2.34 | 0.161 | 0.873 |

| Years of education (years) | 13.86 ± 1.42 | 13.75 ± 1.53 | 0.398 | 0.691 |

| Smoking history (yes/no) | 16 | 18 | 0.175 | 0.676 |

| Drinking history (yes/no) | 15 | 17 | 0.181 | 0.671 |

| Complication | ||||

| Hypertension (yes/no) | 12 | 11 | 0.056 | 0.813 |

| Diabetes (yes/no) | 4 | 5 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| Depression (yes/no) | 14 | 15 | 0.048 | 0.827 |

| Marital status (married/unmarried) | 28 | 24 | 0.615 | 0.433 |

| Ethnicity (Han/other) | 47 | 45 | 0.377 | 0.539 |

| Course of disease | 5.27 ± 1.52 | 5.23 ± 1.49 | 0.133 | 0.894 |

| Pathogeny | 0.253 | 0.969 | ||

| Family genetic history | 9 | 11 | ||

| Psychological factor | 21 | 20 | ||

| Environmental factor | 18 | 17 | ||

| Internal factors | 4 | 4 | ||

| Clinical scale score before treatment | ||||

| Positive symptom score | 17.18 ± 2.65 | 17.97 ± 2.81 | 1.475 | 0.1433 |

| Negative symptom score | 19.71 ± 1.93 | 20.32 ± 1.85 | 1.645 | 0.103 |

| General pathological symptom evaluation | 36.36 ± 7.06 | 37.65 ± 7.82 | 0.883 | 0.3793 |

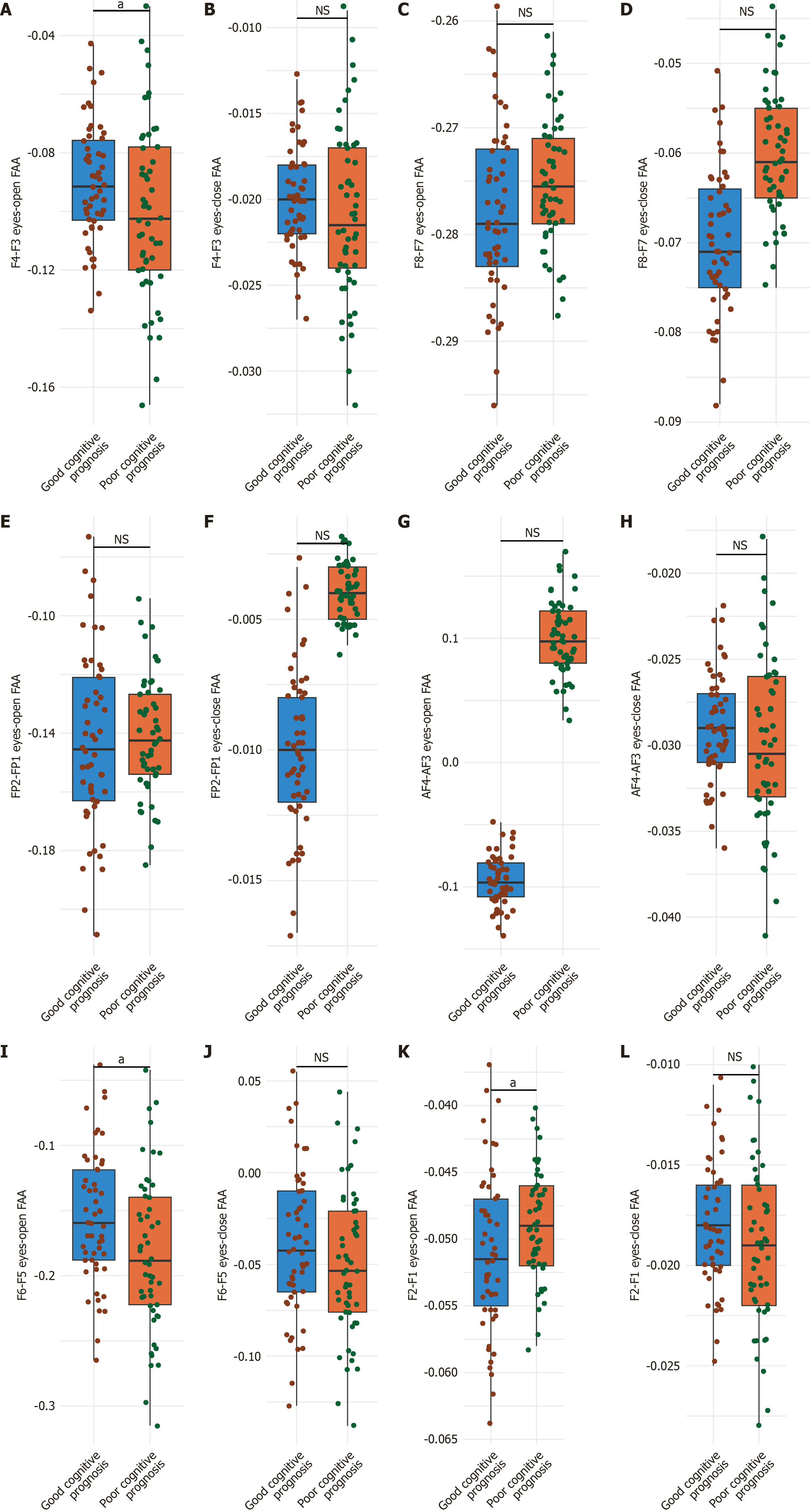

For the F4-F3, the good cognitive prognosis group demonstrated a mean eyes-open FAA of -0.09 ± 0.02, compared to -0.10 ± 0.03 in the poor prognosis group, a difference that reached statistical significance (P = 0.0482; Cohen’s d = 0.35; Figure 1A and B). By contrast, the eyes-closed FAA values did not differ significantly between groups, with means of -0.02 ± 0.003 and -0.021 ± 0.005 for the good and poor prognosis groups, respectively (P = 0.219; Cohen’s d = 0.21). These findings suggest a significant group difference in frontal EEG asymmetry under eyes-open conditions, potentially indicative of state-dependent neural dynamics associated with cognitive prognosis in schizophrenia.

For the F8-F7 eyes-open FAA, the good cognitive prognosis group exhibited a mean value of -0.278 ± 0.08, while the poor prognosis group showed a comparable mean of -0.275 ± 0.06 (P = 0.8292; Cohen’s d = 0.04; Figure 1C and D). Similarly, under eyes-closed conditions, FAA values were -0.070 ± 0.008 for the good prognosis group and -0.060 ± 0.007 for the poor prognosis group (P = 0.4991; Cohen’s d = 0.13). These findings indicate that EEG asymmetry in the anterior temporal region was comparable between groups, with no statistically significant differences observed.

For the FP2-FP1 eyes-open FAA, the good cognitive prognosis group had a mean value of -0.143 ± 0.03, while the poor prognosis group showed a similar mean of -0.141 ± 0.02 (P = 0.69; Cohen’s d = 0.07; Figure 1E and F). Under eyes-closed conditions, FAA values were -0.01 ± 0.003 for the good prognosis group and 0.004 ± 0.001 for the poor prognosis group (P = 0.1523; Cohen’s d = 0.28). These results suggest that EEG asymmetry in the prefrontal cortex does not significantly differ between the two cognitive prognosis groups.

For the AF4-AF3 eyes-open FAA, the good cognitive prognosis group had a mean value of -0.095 ± 0.02, compared to -0.100 ± 0.03 in the poor prognosis group (P = 0.3197; Cohen’s d = 0.18; Figure 1G and H). Under eyes-closed conditions, the FAA was -0.029 ± 0.003 for the good prognosis group and -0.030 ± 0.005 for the poor prognosis group (P = 0.219; Cohen’s d = 0.21). These findings indicate that EEG asymmetry in the medial prefrontal cortex was comparable between the two groups, with no statistically significant differences observed.

For the F6-F5, the good cognitive prognosis group exhibited a mean eyes-open FAA of -0.155 ± 0.05, whereas the poor prognosis group showed a mean of -0.183 ± 0.06 (P = 0.0111; Cohen’s d = 0.51; Figure 1I and J). In contrast, the eyes-closed FAA did not differ significantly between the groups, with mean values of -0.039 ± 0.04 for the good prognosis group and -0.050 ± 0.04 for the poor prognosis group (P = 0.1639; Cohen’s d = 0.27). These results suggest a significant difference in EEG asymmetry within the middle frontal gyrus under eyes-open conditions, potentially linked to cognitive outcomes.

For the F2-F1, the good cognitive prognosis group had a mean eyes-open FAA of -0.051 ± 0.006, compared to -0.049 ± 0.004 in the poor prognosis group (P = 0.0482; Cohen’s d = 0.35; Figure 1K and L). Conversely, the eyes-closed FAA did not differ significantly between groups, with mean values of -0.018 ± 0.003 for the good prognosis group and -0.019 ± 0.004 for the poor prognosis group (P = 0.1523; Cohen’s d = 0.28). These findings indicate a significant difference in EEG asymmetry in the lateral prefrontal cortex under eyes-open conditions, which appears to be associated with cognitive prognosis.

The good cognitive prognosis group demonstrated higher mean connectivity in the left FPN, with a value of 14.32 ± 2.94 compared with 12.71 ± 3.47 in the poor prognosis group (P = 0.012; Table 2). Similarly, right FPN connectivity was also greater in the good prognosis group, with a mean of 12.81 ± 2.68 vs 11.28 ± 3.31 in the poor prognosis group (P = 0.011). However, no significant difference was found in the LI of the FPN, with both groups exhibiting comparable values (0.06 ± 0.01 in the good prognosis group and 0.06 ± 0.02 in the poor prognosis group; P = 0.685). These results suggest that while bilateral FPN connectivity is associated with cognitive prognosis, the degree of hemispheric dominance, as measured by the LI, was not.

A negative correlation was found between eyes-open F4-F3 FAA and poor cognitive prognosis [rho = -0.203, P = 0.039, 95% confidence interval (CI): -0.371 to -0.024], indicating that greater left-sided asymmetry in this region is associated with worse outcomes (Table 3). A stronger negative correlation was observed for eyes-open F6-F5 FAA (rho = -0.244, P = 0.013, 95%CI: -0.401 to -0.073). By contrast, eyes-open F2-F1 FAA demonstrated a positive correlation (rho = 0.203, P = 0.039, 95%CI: 0.024-0.371). Furthermore, both left and right FPN connectivity showed significant negative correlations with poor cognitive prognosis. The left FPN had a rho value of -0.239 (P = 0.015, 95%CI: -0.401 to -0.062), while the right FPN a rho value of -0.258 (P = 0.008, 95%CI: -0.421 to -0.082). These results underscore the potential prognostic relevance of frontal EEG asymmetry and FPN connectivity in schizophrenia.

Our study reveals significant associations between frontal EEG asymmetry, FPN connectivity, and cognitive prognosis in individuals with schizophrenia. Specifically, eyes-open FAA at key frontal electrode pairs (F4-F3, F6-F5, and F2-F1), along with reduced bilateral FPN connectivity, differentiated patients with poorer cognitive outcomes following treatment. These findings contribute to a deeper understanding of the neurophysiological mechanisms underlying cognitive recovery in schizophrenia and highlight potential biomarkers for prognosis and therapeutic targeting.

The observed negative correlation between eyes-open F4-F3 FAA (reflecting relative left frontal hypoactivation) and cognitive prognosis is consistent with established models of prefrontal dysfunction in schizophrenia[18]. Dysregulation of dopaminergic pathways, which is a central pathophysiological mechanism[19], disrupts frontal cortical efficiency, particularly impacting lateral prefrontal regions essential for executive functions[20]. Notably, the state-dependent nature of this association, emerging only during eyes-open conditions, aligns with prior evidence that environmental engagement modulates frontal asymmetry[21]. This underscores the relevance of ecologically valid neural states in the identification and interpretation of cognitive biomarkers.

While FAA has been extensively investigated in affective disorders[22], its prognostic utility for cognitive outcomes in schizophrenia under eyes-open conditions represents a novel application. Our electrode-specific analysis diverges from recent studies emphasizing EEG microstates[23] or large-scale network measures[24], suggesting that FAA captures localized and complementary prognostic information. Significant asymmetry at F6-F5 and F2-F1 further highlights the involvement of lateral and dorsolateral prefrontal regions, which are key hubs for working memory and attentional control, functions strongly associated with real-world functional outcomes[25,26].

The finding of reduced bilateral FPN connectivity in the poor prognosis group reinforces a network-level perspective. The FPN is integral to cognitive control and adaptive processing[27,28]. Its impaired connectivity supports the “dysconnection hypothesis” of schizophrenia, which posits inefficient integration across distributed brain networks[29]. Notably, the absence of significant differences in the LI, despite bilateral reductions, suggests that the overall integrity of bilateral FPNs rather than hemispheric dominance is paramount for cognitive recovery.

These patterns likely reflect intertwined mechanisms: Perturbed dopaminergic signaling may underlie both frontal asymmetry and FPN dysconnectivity, impairing neural synchrony and efficiency[30]. The FAA findings could indicate either a primary deficit in left frontal engagement or a maladaptive right-hemisphere compensation attempt[31]. This variance may represent heterogeneity in neuroplastic responses to illness and treatment[32]. Our findings suggest that eyes-open FAA measures (F4-F3, F6-F5, and F2-F1) and FPN connectivity could serve as adjunctive prognostic tools. Integrating these markers may help stratify patients early in terms of cognitive recovery potential, which could guide the allocation of intensive cognitive remediation resources toward individuals with poor neurophysiological prognoses[33]. These neurophysiological measures may also become targets for neuromodulation interventions, such as transcranial magnetic stimulation or transcranial direct current stimulation, with the goal of normalizing asymmetry or enhancing connectivity. However, translating this into clinical practice requires addressing key challenges related to reliability, accessibility, and the standardization of protocols.

While our study offers valuable insights into the relationship between frontal lobe EEG asymmetry and cognitive function prognosis in schizophrenia, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the relatively small sample size may constrain subgroup analyses and limit the generalizability of the findings to the broader schizophrenia population. The retrospective design and naturalistic medication regimen introduce potential variability; future prospective studies that control for antipsychotic type and dosage are necessary. The use of a median split to categorize cognitive prognosis may impose arbitrary thresholds. Alternative approaches, such as modeling continuous MCCB scores or applying ma

Moreover, these insights underscore the need for ongoing longitudinal studies to examine how neural and cognitive functions interact throughout the course of treatment and disease progression. Such research can determine whether the observed EEG asymmetries are modifiable through targeted interventions aimed at restoring normative brain activity or whether they represent stable traits of the disorder. Exploring therapeutic strategies that address neurotransmitter imbalances or enhance network connectivity may ultimately contribute to improved treatment efficacy and cognitive recovery in individuals with schizophrenia.

This study demonstrates that state-dependent eyes-open frontal EEG asymmetry, particularly at F4-F3, F6-F5, and F2-F1, and reduced bilateral FPN connectivity are associated with poor cognitive prognosis in schizophrenia. These findings extend the application of FAA to cognitive outcome prediction and link it with network-level dysfunction. The results highlight the potential of these markers as adjunctive prognostic tools and therapeutic targets, but important limitations related to study design, sample characteristics, and measurement methodology must be considered. Future large-scale, longitudinal, and multimodal studies that incorporate task-based paradigms and control for treatment variables are needed to validate these markers, clarify their temporal dynamics, and assess their clinical utility in guiding personalized intervention strategies. This study contributes to ongoing efforts to integrate neurophysiological metrics into the prognostic assessment of cognitive function in schizophrenia.

| 1. | Li B, Liu CM, Wang LN, Jin WQ, Pan WG, Wang W, Ren YP, Ma X, Tang YL. Cognitive control impairment in ax-continuous performance test in patients with schizophrenia: A pilot EEG study. Brain Behav. 2023;13:e3276. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Thirioux B, Langbour N, Bokam P, Wassouf I, Guillard-Bouhet N, Wangermez C, Leblanc PM, Doolub D, Harika-Germaneau G, Jaafari N. EEG microstate co-specificity in schizophrenia and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2024;274:207-225. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Bagherzadeh S, Shalbaf A. EEG-based schizophrenia detection using fusion of effective connectivity maps and convolutional neural networks with transfer learning. Cogn Neurodyn. 2024;18:2767-2778. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Article Influence: 2.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Xue R, Li X, Chen J, Liang S, Yu H, Zhang Y, Wei W, Xu Y, Deng W, Guo W, Li T. Shared and Distinct Topographic Alterations of Alpha-Range Resting EEG Activity in Schizophrenia, Bipolar Disorder, and Depression. Neurosci Bull. 2023;39:1887-1890. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Lechner S, Northoff G. Temporal imprecision and phase instability in schizophrenia resting state EEG. Asian J Psychiatr. 2023;86:103654. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Hamilton HK, Mathalon DH, Ford JM. P300 in schizophrenia: Then and now. Biol Psychol. 2024;187:108757. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 17] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 10.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Li G, Lu C, Li S, Kang L, Li Q, Bai M, Xiong P. Correlation study of brain-derived neurotrophic factor, EEG γ activity and cognitive function in first-episode schizophrenia. Brain Res. 2023;1820:148561. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Li F, Wang G, Jiang L, Yao D, Xu P, Ma X, Dong D, He B. Disease-specific resting-state EEG network variations in schizophrenia revealed by the contrastive machine learning. Brain Res Bull. 2023;202:110744. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Santoro V, Hou MD, Premoli I, Belardinelli P, Biondi A, Carobin A, Puledda F, Michalopoulou PG, Richardson MP, Rocchi L, Shergill SS. Investigating cortical excitability and inhibition in patients with schizophrenia: A TMS-EEG study. Brain Res Bull. 2024;212:110972. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 3.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Prieto-Alcántara M, Ibáñez-Molina A, Crespo-Cobo Y, Molina R, Soriano MF, Iglesias-Parro S. Alpha and gamma EEG coherence during on-task and mind wandering states in schizophrenia. Clin Neurophysiol. 2023;146:21-29. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Shen M, Wen P, Song B, Li Y. Automatic identification of schizophrenia based on EEG signals using dynamic functional connectivity analysis and 3D convolutional neural network. Comput Biol Med. 2023;160:107022. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Marín O. Parvalbumin interneuron deficits in schizophrenia. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2024;82:44-52. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Agarwal M, Singhal A. Fusion of pattern-based and statistical features for Schizophrenia detection from EEG signals. Med Eng Phys. 2023;112:103949. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 19] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Wang J, Dong W, Li Y, Wydell TN, Quan W, Tian J, Song Y, Jiang L, Li F, Yi C, Zhang Y, Yao D, Xu P. Discrimination of auditory verbal hallucination in schizophrenia based on EEG brain networks. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2023;331:111632. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Article Influence: 0.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Sahu PK, Jain K. Schizophrenia diagnosis using the GRU-layer's alpha-EEG rhythm's dependability. Psychiatry Res Neuroimaging. 2024;344:111886. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Soria Bretones C, Roncero Parra C, Cascón J, Borja AL, Mateo Sotos J. Automatic identification of schizophrenia employing EEG records analyzed with deep learning algorithms. Schizophr Res. 2023;261:36-46. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Yeh TC, Huang CC, Chung YA, Im JJ, Lin YY, Ma CC, Tzeng NS, Chang CC, Chang HA. High-Frequency Transcranial Random Noise Stimulation over the Left Prefrontal Cortex Increases Resting-State EEG Frontal Alpha Asymmetry in Patients with Schizophrenia. J Pers Med. 2022;12:1667. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | van der Vinne N, Vollebregt MA, van Putten MJAM, Arns M. Frontal alpha asymmetry as a diagnostic marker in depression: Fact or fiction? A meta-analysis. Neuroimage Clin. 2017;16:79-87. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 177] [Cited by in RCA: 195] [Article Influence: 21.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Gordillo D, da Cruz JR, Chkonia E, Lin WH, Favrod O, Brand A, Figueiredo P, Roinishvili M, Herzog MH. The EEG multiverse of schizophrenia. Cereb Cortex. 2023;33:3816-3826. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 22] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Rahul J, Sharma D, Sharma LD, Nanda U, Sarkar AK. A systematic review of EEG based automated schizophrenia classification through machine learning and deep learning. Front Hum Neurosci. 2024;18:1347082. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 26] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Akil AM, Cserjési R, Nagy T, Demetrovics Z, Németh D, Logemann HNA. The relationship between frontal alpha asymmetry and behavioral and brain activity indices of reactive inhibitory control. J Neurophysiol. 2024;132:362-374. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Jannati A, Oberman LM, Rotenberg A, Pascual-Leone A. Assessing the mechanisms of brain plasticity by transcranial magnetic stimulation. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2023;48:191-208. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 99] [Cited by in RCA: 159] [Article Influence: 53.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Khanna A, Pascual-Leone A, Michel CM, Farzan F. Microstates in resting-state EEG: current status and future directions. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2015;49:105-113. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 316] [Cited by in RCA: 627] [Article Influence: 52.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (1)] |

| 24. | Betzel RF, Erickson MA, Abell M, O'Donnell BF, Hetrick WP, Sporns O. Synchronization dynamics and evidence for a repertoire of network states in resting EEG. Front Comput Neurosci. 2012;6:74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 77] [Cited by in RCA: 76] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Li H, Wang C, Ma L, Xu C, Li H. EEG analysis in patients with schizophrenia based on microstate semantic modeling method. Front Hum Neurosci. 2024;18:1372985. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | Portnova GV, Maslennikova AV. The Photic Stimulation Has an Impact on the Reproduction of 10 s Intervals Only in Healthy Controls but Not in Patients with Schizophrenia: The EEG Study. Brain Sci. 2023;13:112. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Teixeira FL, Costa MRE, Abreu JP, Cabral M, Soares SP, Teixeira JP. A Narrative Review of Speech and EEG Features for Schizophrenia Detection: Progress and Challenges. Bioengineering (Basel). 2023;10:493. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Donati FL, Mayeli A, Sharma K, Janssen SA, Lagoy AD, Casali AG, Ferrarelli F. Natural Oscillatory Frequency Slowing in the Premotor Cortex of Early-Course Schizophrenia Patients: A TMS-EEG Study. Brain Sci. 2023;13:534. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | Friston KJ, Frith CD. Schizophrenia: a disconnection syndrome? Clin Neurosci. 1995;3:89-97. [PubMed] |

| 30. | De Pieri M, Rochas V, Sabe M, Michel C, Kaiser S. Pharmaco-EEG of antipsychotic treatment response: a systematic review. Schizophrenia (Heidelb). 2023;9:85. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 12] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Shor O, Yaniv-Rosenfeld A, Valevski A, Weizman A, Khrennikov A, Benninger F. EEG-based spatio-temporal relation signatures for the diagnosis of depression and schizophrenia. Sci Rep. 2023;13:776. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Ruiz de Miras J, Ibáñez-Molina AJ, Soriano MF, Iglesias-Parro S. Fractal dimension analysis of resting state functional networks in schizophrenia from EEG signals. Front Hum Neurosci. 2023;17:1236832. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Iglesias-Parro S, Soriano MF, Ibáñez-Molina AJ, Pérez-Matres AV, Ruiz de Miras J. Examining Neural Connectivity in Schizophrenia Using Task-Based EEG: A Graph Theory Approach. Sensors (Basel). 2023;23:8722. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Alonso S, Vidaurre D. Toward stability of dynamic FC estimates in neuroimaging and electrophysiology: Solutions and limits. Netw Neurosci. 2023;7:1389-1403. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Das A, de Los Angeles C, Menon V. Electrophysiological foundations of the human default-mode network revealed by intracranial-EEG recordings during resting-state and cognition. Neuroimage. 2022;250:118927. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 24] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 7.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Maheshwari M, Deshmukh T, Leuthardt EC, Shimony JS. Task-based and Resting State Functional MRI in Children. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am. 2021;29:527-541. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/