Published online Dec 19, 2025. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v15.i12.112122

Revised: August 16, 2025

Accepted: September 25, 2025

Published online: December 19, 2025

Processing time: 132 Days and 19.1 Hours

In this article, we comment on the recent network analysis by Li et al, which exp

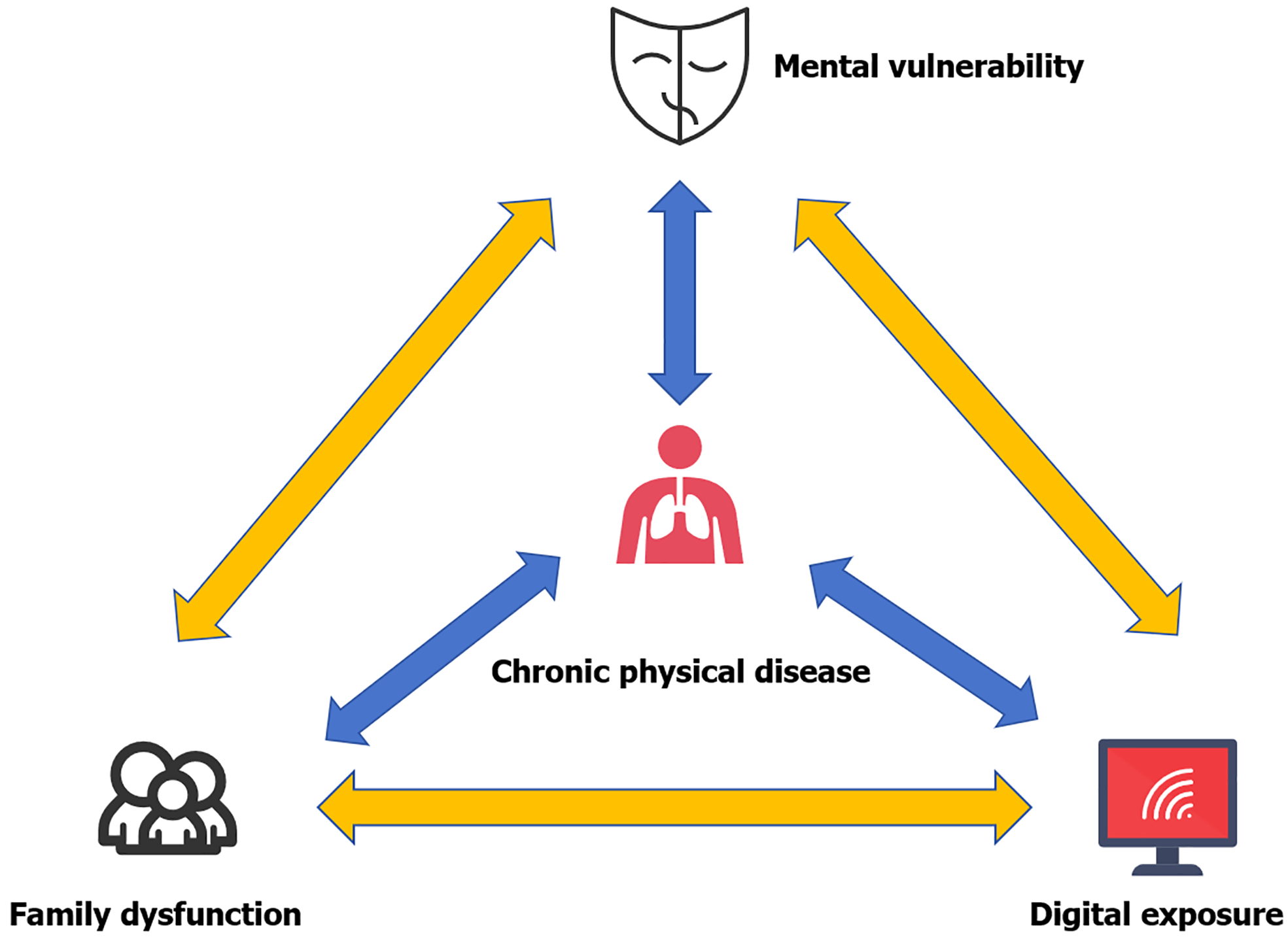

Core Tip: This commentary underscores the dynamic interplay among emotional vulnerability, family dysfunction, and digital exposure in individuals with noncommunicable chronic diseases. By identifying these psychosocial factors as modifiable and transdiagnostic intervention targets, the article advocates for integrative strategies emotional resilience training, family-based support, and digital literacy enhancement to disrupt reinforcing risk pathways and improve mental health outcomes in medically vulnerable populations.

- Citation: Zhang WY, Yang K, Zhai YC, Miao QS, Cui YH. Mental vulnerability, family dysfunction, and digital exposure: Overlooked burdens in populations with noncommunicable chronic diseases. World J Psychiatry 2025; 15(12): 112122

- URL: https://www.wjgnet.com/2220-3206/full/v15/i12/112122.htm

- DOI: https://dx.doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v15.i12.112122

Noncommunicable chronic diseases (NCDs), such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and cancer, represent a leading global health burden[1]. According to a 2022 report by the World Health Organization, chronic diseases account for over 17 million deaths worldwide each year[2]. In China, the prevalence of NCDs has risen sharply between 1992 and 2012, making them the primary cause of mortality among the Chinese population[3]. Beyond their physical consequences, individuals with NCDs frequently experience significant psychological distress, including depression and anxiety, which profoundly undermine both quality of life and treatment adherence[4,5]. While prior research has examined biomedical and demographic determinants of mental health in this population[6], far less attention has been devoted to key psychosocial domains that may exert similarly profound effects.

Li et al[7] conducted a cross-sectional survey of 6182 Chinese individuals with NCDs using data from the psychology and behavior investigation of Chinese residents. Through network analysis, they identified core psychosocial factors in individuals with NCDs (e.g., media exposure, family health, problematic internet use, intimate partner violence, anxiety, nervousness, low energy) as well as bridge factors (e.g., media exposure, problematic internet use, intimate partner violence), and proposed interventions targeting these key symptoms. Notably, this study represents the first preliminary investigation of the network relationships among these key psychosocial domains namely, mental vulnerability (e.g., emotional dysregulation, fatigue), family dysfunction (e.g., family conflict, intimate partner violence), and digital exposure (e.g., media consumption, problematic internet use) highlighting their potential interconnections. However, the interactions among these domains remain insufficiently explored, and to date, no other study has systematically examined their interrelationships in NCD populations.

In this commentary, we argue that these domains constitute modifiable psychosocial burdens in individuals with NCDs, and that addressing their interconnections may provide valuable targets for interventions aimed at improving psychological outcomes. By highlighting their interdependence within a dynamic network framework, we call for greater attention to these domains in both research and intervention development. Specifically, we examine: (1) The unique roles of these domains in shaping psychological outcomes among individuals with NCDs; (2) The interactions among these domains and their reinforcing nature within psychosocial networks; (3) Potential intervention strategies that target these interconnected domains; and (4) Limitations of the current evidence and directions for future research. Through this synthesis, we aim to promote a more integrative and actionable understanding of psychosocial determinants of mental health in NCD populations.

On the one hand, preexisting psychological vulnerabilities including heightened sensitivity to emotional distress, impaired affect regulation, and maladaptive coping styles may predispose individuals to worse psychological outcomes once they are diagnosed with a NCD. Such vulnerabilities can arise from prior psychiatric conditions (e.g., history of depression or anxiety disorders), early-life adversity, or enduring personality traits such as high neuroticism[8,9]. Evidence indicates that these factors amplify emotional reactivity to health-related stressors, increase perceived illness threat, and reduce the capacity to adaptively cope with chronic symptoms[10,11]. Neurobiological mechanisms, including preexisting dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis and altered inflammatory profiles, may further heighten susceptibility to mental distress when confronted with the demands of managing an NCD[12,13]. However, the literature on NCDs has paid relatively little attention to how such baseline vulnerabilities shape the trajectory of psychological adjustment, representing a critical gap in the understanding of the heterogeneity of mental health outcomes in these populations.

On the other hand, psychological consequences secondary to NCD onset also contribute substantially to mental vulnerability. These include illness-related fatigue[14,15], prognostic uncertainty[16,17], functional limitations[18,19], and perceived social stigma[18,20]. For example, individuals with diabetes may experience guilt and shame associated with lifestyle-related attributions[21], while those with cancer often endure existential distress linked to mortality salience and identity disruption[22]. Such illness-driven stressors can precipitate emotion dysregulation defined as difficulty modulating emotional responses in accordance with contextual demands which is consistently associated with poorer self-care, lower treatment adherence, and worsened clinical outcomes[23]. Over time, these maladaptive patterns can impair executive functioning[24,25], goal-directed behavior[26], and interpersonal relationships[27], creating a reinforcing cycle of psychosocial and physical decline.

Family functioning plays a pivotal role in shaping the psychosocial trajectory of individuals living with NCDs. Two critical yet underrecognized domains of dysfunction family health[28,29] and intimate partner violence[30] have emerged as salient contributors to emotional burden, behavioral dysregulation, and poor clinical outcomes in this population.

On the one hand, family dysfunction can lead to or exacerbate psychological distress among individuals with NCDs. Family health, which is conceptualized as the system-level capacity of the family to adapt, communicate, and maintain cohesion in the face of adversity, is frequently compromised in households affected by chronic illness[31]. The persistent demands of disease management ranging from treatment complexity to financial strain can erode family resilience, increase relational conflict, and diminish collective problem-solving abilities[32]. Studies have shown that poor family functioning is associated with reduced treatment adherence, heightened psychological distress, and accelerated disease progression across various NCDs[33]. Moreover, in pediatric and adolescent populations, impaired family functioning has been linked to emotional dysregulation, school difficulties, and diminished quality of life[34].

On the other hand, the presence of NCDs and the chronic stressors they impose can in turn undermine family functioning. Intimate partner violence presents a more insidious yet pervasive form of family dysfunction[30]. In

The growing ubiquity of digital technologies has profoundly reshaped daily routines, particularly among individuals living with NCDs. Digital exposure encompassing both beneficial engagement (e.g., health information seeking, telemedicine use)[41,42] and potentially harmful use (e.g., excessive screen time, problematic internet use)[43,44] has emerged as a critical but underexplored determinant of mental and physical health in this population.

On the one hand, digital tools offer unprecedented opportunities for individuals with NCDs to access health resources, manage chronic conditions, and maintain social connectedness, especially amid mobility restrictions or limited in-person services[45,46]. Studies have shown that digital health platforms can improve medication adherence, enable remote symptom tracking, and facilitate behavioral interventions for lifestyle modification[46,47].

On the other hand, excessive or dysregulated digital exposure may exacerbate health vulnerabilities. High levels of screen time are associated with various chronic diseases, such as diabetes and cardiovascular conditions[48,49]. More

Notably, the adverse effects of digital technologies are not uniform and cannot be solely explained by metrics such as duration of use. Instead, their impact is shaped by the sociocultural milieu, the type and purpose of digital engagement, and individual vulnerability factors. Consequently, findings across studies remain inconsistent, with some reporting benefits and others documenting harm. Furthermore, as digital ecosystems rapidly evolve, knowledge gaps are widening. While the psychological effects of social media use are relatively well studied, little is known about emerging technologies such as the metaverse and their potential implications for individuals with NCDs. Addressing these gaps requires nuanced, culturally sensitive, and forward-looking research to provide a balanced understanding of digital exposure in this vulnerable population.

In addition to its psychological effects, digital engagement can directly influence the treatment, rehabilitation, and functional outcomes of individuals with NCDs. Telemedicine platforms, remote monitoring applications, and digital health education tools have been shown to enhance medication adherence, support rehabilitation programs, and improve overall quality of life[54]. Appropriate digital use can facilitate behavioral interventions, enable timely symptom tracking, and promote self-management of chronic conditions. At a physiological level, maladaptive or stress-inducing digital exposure may affect neuroendocrine pathways, including the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, and modulate inflammatory responses, linking digital behaviors with both mental and physical health outcomes[55]. These findings highlight the dual role of digital exposure as both a potential therapeutic adjunct and a source of risk, underscoring the need for careful, individualized guidance and culturally sensitive interventions.

The interplay between digital exposure, mental vulnerability, and dysfunctional family functioning may exacerbate psychosocial and health outcomes in individuals with NCDs. These interactions are not merely additive but also mutually reinforcing, creating a complex cycle of risk.

Mental vulnerability can both stem from and contribute to family dysfunction[56,57]. Individuals with NCDs who experience high levels of psychological distress often report impaired family communication, reduced emotional support, and increased conflict[33]. Conversely, living in an unsupportive or hostile family environment may heighten feelings of helplessness, stress, and emotional instability, creating a bidirectional feedback loop that aggravates both mental and physical health symptoms[35,58].

Family dysfunction can significantly influence digital media usage patterns. In families marked by poor cohesion, limited supervision, or high levels of conflict, individuals especially adolescents may resort to excessive screen use or problematic internet behaviors as a form of escapism or passive coping[59]. While this compensatory digital engagement may provide temporary distraction, it can also disrupt sleep[60], reduce physical activity, and interfere with social interactions[60,61], which may indirectly exacerbate existing family tension.

Digital exposure and mental vulnerability often reinforce each other in a maladaptive cycle. Individuals with high psychological burden may use digital platforms to avoid emotional discomfort or to seek online validation, potentially exacerbating symptoms of anxiety, depression, and social withdrawal[62-64]. Problematic internet use has been linked to poorer emotional regulation and increased loneliness in youth and adults with NCDs[62,63,65]. Over time, this cycle may intensify digital dependence and impede real-world engagement, thereby worsening clinical outcomes.

The interaction between digital exposure, mental vulnerability, and family dysfunction represent a core manifestation of psychosocial imbalance in individuals with NCDs. This triadic interplay not only reflects disturbances in psychological well-being but also exerts a reciprocal influence on the progression and management of chronic physical illnesses, ultimately compromising self-regulation, treatment adherence, and health outcomes in individuals with NCDs (Figure 1).

For people living with NCDs, individual-level interventions are critical to improving psychological well-being, disease management, and overall quality of life. Key strategies include enhancing digital health literacy to improve access to and use of health information, particularly for older adults[66,67]; implementing cognitive-behavioral therapy to alleviate anxiety and depression while promoting adaptive coping[68]; delivering mindfulness-based stress reduction programs to reduce stress and enhance emotional regulation[69]; and providing emotion regulation training to strengthen resilience and self-management[70]. Together, these interventions target both psychological vulnerabilities and behavioral skills, supporting better mental health outcomes and more effective chronic disease management.

At the family level, interventions aim to strengthen relational dynamics, caregiving support, and communication patterns that are critical for effectively managing of NCDs. Systemic family therapy can help families identify and modify maladaptive interaction patterns, enhance problem-solving, and improve cohesion in the face of chronic illness[71]. Parenting interventions and caregiver support programs provide practical skills and emotional guidance, reducing stress and burden for both patients and caregivers. Family-centered psychoeducation, including disease management, lifestyle adjustments, and coping strategies, can improve adherence to treatment regimens and reduce psychological distress[72]. These interventions not only target family dysfunction but also indirectly enhance individual well-being by creating a supportive home environment conducive to recovery and long-term disease management.

Given that NCDs disproportionately affect older adults who often face social isolation, loneliness, and reduced access to care population-level psychosocial interventions are both essential and timely. Digital interventions designed to reduce loneliness, such as videoconferencing with family or socially assistive robots, have shown promise in enhancing social connectedness and improving quality of life among older adults, although high-quality evidence remains unevenly distributed and further research is needed[73]. Policy-level strategies may include integrating funding for such digital platforms into aging and public health programs, training community social care workers to deliver psychosocial support, and addressing digital equity by ensuring that older adults have both the necessary devices and digital literacy[74]. Community-based models such as virtual group exercises can promote both physical engagement and social interaction, creating accessible psychosocial support for homebound seniors[75]. Moreover, randomized field studies demonstrate that mobile health platforms delivering self-management content improve behavioral outcomes and clinical markers in patients with chronic diseases, underscoring the feasibility of scalable digital psychosocial interventions[75]. Together, these population-targeted measures, which bridge policy, community infrastructure, and digital tools, constitute actionable, evidence-supported strategies to strengthen psychological resilience, social support, and functional health among older adults with NCDs.

Although interventions at the individual, family, and population or policy levels have demonstrated efficacy, current research often treats these strategies in isolation, limiting their potential impact. A systems-based approach is needed to integrate these components into a coherent, multilevel framework. Network analysis offers a promising tool to identify central and bridge symptoms that sustain maladaptive feedback loops across psychological, familial, and social domains. Targeting these mechanisms may not only improve mental health outcomes but also enhance disease self-management and slow the progression of NCDs. Such an integrated, cross-diagnostic model underscores the value of transdisciplinary collaboration, ensuring that interventions address both biological and psychosocial determinants of health in a synergistic and sustainable manner.

While this conceptual synthesis highlights the complex interplay among digital exposure, mental vulnerability, and family dysfunction in individuals with NCDs, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the existing empirical literature is largely cross-sectional, precluding definitive causal inferences and obscuring the temporal dynamics between psychosocial stressors and disease progression. Second, most studies rely on self-reported data, which are susceptible to recall bias and may underrepresent subclinical yet functionally significant disturbances. Third, the cultural and socioeconomic contexts that modulate these interactions remain underexplored, limiting the generalizability of current findings across diverse populations, particularly in low- and middle-income countries. Although prior work (e.g., Li et al[7]) suggests that traditional demographic variables such as gender, ethnicity, and residence exert limited influence on overall network strength, the broader role of sociocultural factors in shaping psychological distress and family dynamics cannot be dismissed.

Future research should prioritize longitudinal, multi-informant designs that integrate biological, behavioral, and digital biomarkers to capture real-time dynamics within and between psychosocial domains. Network-based analytical approaches offer particular promise in identifying transdiagnostic “bridge nodes” that connect digital exposure, affective symptoms, and relational dysfunction providing novel targets for intervention. Furthermore, intervention studies must move toward precision-based frameworks that tailor strategies to individual vulnerability profiles, accounting for developmental stage, digital habits, family system structure, and comorbidity patterns. Finally, cross-sectoral collaboration between health care, education, and digital technology sectors is essential for the scalable implementation of integrated interventions. Only through such multidimensional and contextually grounded approaches can we advance from descriptive mapping to transformative action in addressing the psychological burden associated with chronic disease.

This synthesis underscores the mental vulnerability, family dysfunction, and digital exposure experienced by individuals with NCDs, and explores their complex, reciprocal interactions within a dysfunctional psychosocial network. These domains should not be viewed as isolated risk factors, but as interconnected elements of a dynamic system reflecting the broader psychosocial burden embedded in chronic illness. Addressing this burden calls for a paradigm shift toward network-informed, system-level interventions that integrate mental health care, digital behavior regulation, and family support. Future research must adopt longitudinal, context-sensitive methodologies, while health policies should prioritize cross-sectoral integration to ensure comprehensive, equitable, and sustainable care for individuals living with NCDs.

| 1. | GBD 2016 Causes of Death Collaborators. Global, regional, and national age-sex specific mortality for 264 causes of death, 1980-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390:1151-1210. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 3389] [Cited by in RCA: 3354] [Article Influence: 372.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 2. | Das M. WHO urges immediate action to tackle non-communicable diseases. Lancet Oncol. 2022;23:1361. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 3. | Wang Y, Wang L, Qu W. New national data show alarming increase in obesity and noncommunicable chronic diseases in China. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2017;71:149-150. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 66] [Cited by in RCA: 112] [Article Influence: 11.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 4. | Mendenhall E, Kohrt BA, Norris SA, Ndetei D, Prabhakaran D. Non-communicable disease syndemics: poverty, depression, and diabetes among low-income populations. Lancet. 2017;389:951-963. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 302] [Cited by in RCA: 329] [Article Influence: 36.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 5. | Yan R, Xia J, Yang R, Lv B, Wu P, Chen W, Zhang Y, Lu X, Che B, Wang J, Yu J. Association between anxiety, depression, and comorbid chronic diseases among cancer survivors. Psychooncology. 2019;28:1269-1277. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 22] [Cited by in RCA: 41] [Article Influence: 5.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 6. | Diaz-Vegas A, Sanchez-Aguilera P, Krycer JR, Morales PE, Monsalves-Alvarez M, Cifuentes M, Rothermel BA, Lavandero S. Is Mitochondrial Dysfunction a Common Root of Noncommunicable Chronic Diseases? Endocr Rev. 2020;41:bnaa005. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 48] [Cited by in RCA: 115] [Article Influence: 19.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 7. | Li HY, Song DY, Weng YQ, Tong YH, Wu YB, Wang HM. Prevalence of depression and anxiety and related influencing factors in the Chinese population with noncommunicable chronic diseases: A network perspective. World J Psychiatry. 2025;15:109789. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 8. | Majnarić LT, Bosnić Z, Guljaš S, Vučić D, Kurevija T, Volarić M, Martinović I, Wittlinger T. Low Psychological Resilience in Older Individuals: An Association with Increased Inflammation, Oxidative Stress and the Presence of Chronic Medical Conditions. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:8970. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 59] [Article Influence: 11.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 9. | Zulkifli MM, Abdul Rahman R, Muhamad R, Abdul Kadir A, Roslan NS, Mustafa N. The lived experience of resilience in chronic disease among adults in Asian countries: a scoping review of qualitative studies. BMC Psychol. 2024;12:773. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 10. | Anwar N, Kuppili PP, Balhara YPS. Depression and physical noncommunicable diseases: The need for an integrated approach. WHO South East Asia J Public Health. 2017;6:12-17. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 23] [Article Influence: 2.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 11. | Mosili P, Mkhize BC, Sibiya NH, Ngubane PS, Khathi A. Review of the direct and indirect effects of hyperglycemia on the HPA axis in T2DM and the co-occurrence of depression. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2024;12:e003218. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 28] [Article Influence: 14.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 12. | Armbrecht E, Shah R, Poorman GW, Luo L, Stephens JM, Li B, Pappadopulos E, Haider S, McIntyre RS. Economic and Humanistic Burden Associated with Depression and Anxiety Among Adults with Non-Communicable Chronic Diseases (NCCDs) in the United States. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2021;14:887-896. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 16] [Article Influence: 3.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 13. | Perrelli M, Goparaju P, Postolache TT, Del Bosque-Plata L, Gragnoli C. Stress and the CRH System, Norepinephrine, Depression, and Type 2 Diabetes. Biomedicines. 2024;12:1187. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 14. | Valdes-Stauber J, Vietz E, Kilian R. The impact of clinical conditions and social factors on the psychological distress of cancer patients: an explorative study at a consultation and liaison service in a rural general hospital. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:226. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 18] [Article Influence: 1.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 15. | Adamowicz JL, Vélez-Bermúdez M, Thomas EBK. Fatigue severity and avoidance among individuals with chronic disease: A meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res. 2022;159:110951. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 19] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 3.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 16. | Do Y, Seo M. A Concept Analysis of Illness Intrusiveness in Chronic Disease: Application of the Hybrid Model Method. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:5900. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 17. | Schoormans D, Jansen M, Mols F, Oerlemans S. Negative illness perceptions are related to more fatigue among haematological cancer survivors: a PROFILES study. Acta Oncol. 2020;59:959-966. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 14] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 18. | Kittel JA, Seplaki CL, van Wijngaarden E, Richman J, Magnuson A, Conwell Y. Fatigue, impaired physical function and mental health in cancer survivors: the role of social isolation. Support Care Cancer. 2024;33:16. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 19. | Kentson M, Tödt K, Skargren E, Jakobsson P, Ernerudh J, Unosson M, Theander K. Factors associated with experience of fatigue, and functional limitations due to fatigue in patients with stable COPD. Ther Adv Respir Dis. 2016;10:410-424. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 46] [Cited by in RCA: 54] [Article Influence: 5.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 20. | Préville M, Mechakra Tahiri SD, Vasiliadis HM, Quesnel L, Gontijo-Guerra S, Lamoureux-Lamarche C, Berbiche D. Association between perceived social stigma against mental disorders and use of health services for psychological distress symptoms in the older adult population: validity of the STIG scale. Aging Ment Health. 2015;19:464-474. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 9] [Cited by in RCA: 10] [Article Influence: 0.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 21. | Solomon E, Salcedo VJ, Reed MK, Brecher A, Armstrong EM, Rising KL. "I'm Going to Be Good to Me": Exploring the Role of Shame and Guilt in Patients With Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Spectr. 2022;35:216-222. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 22. | Gao W, Bennett MI, Stark D, Murray S, Higginson IJ. Psychological distress in cancer from survivorship to end of life care: prevalence, associated factors and clinical implications. Eur J Cancer. 2010;46:2036-2044. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 88] [Cited by in RCA: 91] [Article Influence: 5.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 23. | Kollin SR, Gratz KL, Lee AA. The role of emotion dysregulation in self-management behaviors among adults with type 2 diabetes. J Behav Med. 2024;47:672-681. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Article Influence: 2.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 24. | Esmaili M, Farhud DD, Poushaneh K, Baghdassarians A, Ashayeri H. Executive Functions and Public Health: A Narrative Review. Iran J Public Health. 2023;52:1589-1599. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 25. | Koay JM, Van Meter A. The Effect of Emotion Regulation on Executive Function. J Cogn Psychol (Hove). 2023;35:315-329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 26. | 26 Griffiths KR, Morris RW, Balleine BW. Translational studies of goal-directed action as a framework for classifying deficits across psychiatric disorders. Front Syst Neurosci. 2014;8:101. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 74] [Cited by in RCA: 97] [Article Influence: 8.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 27. | Garofalo C, Velotti P, Zavattini GC, Kosson DS. Emotion dysregulation and interpersonal problems: The role of defensiveness. Pers Indiv Differ. 2017;119:96-105. [RCA] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 5] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Article Influence: 1.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 28. | Huang X, Yang H, Wang HH, Qiu Y, Lai X, Zhou Z, Li F, Zhang L, Wang J, Lei J. The Association Between Physical Activity, Mental Status, and Social and Family Support with Five Major Non-Communicable Chronic Diseases Among Elderly People: A Cross-Sectional Study of a Rural Population in Southern China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12:13209-13223. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 14] [Cited by in RCA: 21] [Article Influence: 1.9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 29. | BeLue R. The role of family in non-communicable disease prevention in Sub-Saharan Africa. Glob Health Promot. 2017;24:71-74. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 13] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 1.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 30. | Goldberg X, Espelt C, Porta-Casteràs D, Palao D, Nadal R, Armario A. Non-communicable diseases among women survivors of intimate partner violence: Critical review from a chronic stress framework. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2021;128:720-734. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 2.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 31. | Ellis KR, Young TL, Langford AT. Family Health Equity in Chronic Disease Prevention and Management. Ethn Dis. 2023;33:194-199. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 2.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 32. | Rosland AM, Heisler M, Piette JD. The impact of family behaviors and communication patterns on chronic illness outcomes: a systematic review. J Behav Med. 2012;35:221-239. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 211] [Cited by in RCA: 191] [Article Influence: 13.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 33. | Golics CJ, Basra MK, Salek MS, Finlay AY. The impact of patients' chronic disease on family quality of life: an experience from 26 specialties. Int J Gen Med. 2013;6:787-798. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 81] [Cited by in RCA: 102] [Article Influence: 7.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 34. | Cousino MK, Hazen RA. Parenting stress among caregivers of children with chronic illness: a systematic review. J Pediatr Psychol. 2013;38:809-828. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 428] [Cited by in RCA: 559] [Article Influence: 43.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 35. | Ogbe E, Harmon S, Van den Bergh R, Degomme O. A systematic review of intimate partner violence interventions focused on improving social support and/ mental health outcomes of survivors. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0235177. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 112] [Cited by in RCA: 119] [Article Influence: 19.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 36. | Ni F, Zhou T, Wang L, Cai T. Intimate partner violence in women with cancer: An integrative review. Asia Pac J Oncol Nurs. 2024;11:100557. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 37. | Johnson WA, Pieters HC. Intimate Partner Violence Among Women Diagnosed With Cancer. Cancer Nurs. 2016;39:87-96. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 15] [Article Influence: 1.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 38. | Campos-Tinajero E, Ortiz-Nuño MF, Flores-Gutierrez DP, Esquivel-Valerio JA, Garcia-Arellano G, Cardenas-de la Garza JA, Aguilar-Rivera E, Galarza-Delgado DA, Serna-Peña G. Impact of intimate partner violence on quality of life and disease activity in women with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2024;33:979-985. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 39. | Sharpless L, Kershaw T, Hatcher A, Alexander KA, Katague M, Phillips K, Willie TC. IPV, PrEP, and Medical Mistrust. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2022;90:283-290. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Article Influence: 3.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 40. | Taccini F, Mannarini S. An Attempt to Conceptualize the Phenomenon of Stigma toward Intimate Partner Violence Survivors: A Systematic Review. Behav Sci (Basel). 2023;13:194. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 17] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 41. | Li P, Zhang C, Gao S, Zhang Y, Liang X, Wang C, Zhu T, Li W. Association Between Daily Internet Use and Incidence of Chronic Diseases Among Older Adults: Prospective Cohort Study. J Med Internet Res. 2023;25:e46298. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 35] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 42. | Mishra SR, Lygidakis C, Neupane D, Gyawali B, Uwizihiwe JP, Virani SS, Kallestrup P, Miranda JJ. Combating non-communicable diseases: potentials and challenges for community health workers in a digital age, a narrative review of the literature. Health Policy Plan. 2019;34:55-66. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 27] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 6.1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 43. | Li L, Zhang Q, Zhu L, Zeng G, Huang H, Zhuge J, Kuang X, Yang S, Yang D, Chen Z, Gan Y, Lu Z, Wu C. Screen time and depression risk: A meta-analysis of cohort studies. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:1058572. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 27] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 44. | Wu H, Gu Y, Du W, Meng G, Wu H, Zhang S, Wang X, Zhang J, Wang Y, Huang T, Niu K. Different types of screen time, physical activity, and incident dementia, Parkinson's disease, depression and multimorbidity status. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2023;20:130. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 13] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 45. | Maisto M, Diana B, Di Tella S, Matamala-Gomez M, Montana JI, Rossetto F, Mavrodiev PA, Cavalera C, Blasi V, Mantovani F, Baglio F, Realdon O. Digital Interventions for Psychological Comorbidities in Chronic Diseases-A Systematic Review. J Pers Med. 2021;11:30. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 4] [Cited by in RCA: 20] [Article Influence: 4.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 46. | Hussein ESE, Al-Shenqiti AM, Ramadan RME. Applications of Medical Digital Technologies for Noncommunicable Diseases for Follow-Up during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19:12682. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 6] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Article Influence: 1.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 47. | Tighe SA, Ball K, Kensing F, Kayser L, Rawstorn JC, Maddison R. Toward a Digital Platform for the Self-Management of Noncommunicable Disease: Systematic Review of Platform-Like Interventions. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e16774. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 43] [Article Influence: 7.2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 48. | Sehn AP, Silveira JFC, Brand C, Lemes VB, Borfe L, Tornquist L, Pfeiffer KA, Renner JDP, Andersen LB, Burns RD, Reuter CP. Screen time, sleep duration, leisure physical activity, obesity, and cardiometabolic risk in children and adolescents: a cross-lagged 2-year study. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2024;24:525. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 49. | Fu X, Liu Q, Pan Q, Peng R, Huang Z, Guo X, Tan M, Li Q, Jia L, Li Y, Liu L, Kuang J, Wu W, Guo L. An automated human-machine interaction system enhances standardization, accuracy and efficiency in cardiovascular autonomic evaluation: A multicenter, open-label, paired design study. J Transl Int Med. 2025;13:170-179. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 50. | Gioia F, Rega V, Boursier V. Problematic Internet Use and Emotional Dysregulation Among Young People: A Literature Review. Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2021;18:41-54. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 51. | Zhang Y, Li J, Zhang M, Ai B, Jia F. Bidirectional associations between loneliness and problematic internet use: A meta-analytic review of longitudinal studies. Addict Behav. 2024;150:107916. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 1] [Cited by in RCA: 11] [Article Influence: 5.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 52. | de Vries HT, Nakamae T, Fukui K, Denys D, Narumoto J. Problematic internet use and psychiatric co-morbidity in a population of Japanese adult psychiatric patients. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18:9. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 35] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Article Influence: 5.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 53. | Wang P, Wang X, Gao T, Yuan X, Xing Q, Cheng X, Ming Y, Tian M. Problematic Internet Use in Early Adolescents: Gender and Loneliness Differences in a Latent Growth Model. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2023;16:3583-3596. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 54. | Fan K, Zhao Y. Mobile health technology: a novel tool in chronic disease management. Int Med. 2022;2:41-47. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 55. | Kaltenegger HC, Marques MD, Becker L, Rohleder N, Nowak D, Wright BJ, Weigl M. Prospective associations of technostress at work, burnout symptoms, hair cortisol, and chronic low-grade inflammation. Brain Behav Immun. 2024;117:320-329. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 9] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 56. | Vargas-Jiménez E, Castro-Castañeda R, Agulló Tomás E, Medina Centeno R. Job Insecurity, Family Functionality and Mental Health: A Comparative Study between Male and Female Hospitality Workers. Behav Sci (Basel). 2020;10:146. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 57. | Repetti RL, Taylor SE, Seeman TE. Risky families: family social environments and the mental and physical health of offspring. Psychol Bull. 2002;128:330-366. [PubMed] |

| 58. | Xiong P, Chen Y, Shi Y, Liu M, Yang W, Liang B, Liu Y. Global burden of diseases attributable to intimate partner violence: findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2025;60:487-513. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 2] [Cited by in RCA: 8] [Article Influence: 8.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 59. | Schneider LA, King DL, Delfabbro PH. Family factors in adolescent problematic Internet gaming: A systematic review. J Behav Addict. 2017;6:321-333. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 143] [Cited by in RCA: 183] [Article Influence: 20.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 60. | Kokka I, Mourikis I, Nicolaides NC, Darviri C, Chrousos GP, Kanaka-Gantenbein C, Bacopoulou F. Exploring the Effects of Problematic Internet Use on Adolescent Sleep: A Systematic Review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:760. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 34] [Cited by in RCA: 62] [Article Influence: 12.4] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 61. | Xue B, Zheng X, Yang L, Xiao S, Chen J, Zhang X, Li X, Chen Y, Liao Y, Zhang M, Zheng T, Wu Y, Zhang C. The prevalence of suboptimal health status among Chinese secondary school students and its relationship with family health: the mediating role of perceived stress and problematic internet use. BMC Public Health. 2024;24:3321. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 2] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 62. | Ahmed O, Walsh EI, Dawel A, Alateeq K, Espinoza Oyarce DA, Cherbuin N. Social media use, mental health and sleep: A systematic review with meta-analyses. J Affect Disord. 2024;367:701-712. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 42] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 63. | Huang C. A meta-analysis of the problematic social media use and mental health. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2022;68:12-33. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 42] [Cited by in RCA: 130] [Article Influence: 32.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 64. | Fernández-Regueras D, Calero-Elvira A, Guerrero-Escagedo MC. Comparison of clinical indicators between face-to-face and videoconferencing psychotherapy: Success, adherence to treatment and efficiency. Behav Psychol. 2023;30:543-562. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 65. | Yuan H, Kang L, Li Y, Fan Z. Human‐in‐the‐loop machine learning for healthcare: Current progress and future opportunities in electronic health records. Med Adv. 2024;2:318-322. [DOI] [Full Text] |

| 66. | Shao Y, Yang X, Chen Q, Guo H, Duan X, Xu X, Yue J, Zhang Z, Zhao S, Zhang S. Determinants of digital health literacy among older adult patients with chronic diseases: a qualitative study. Front Public Health. 2025;13:1568043. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 67. | Yun S, Ariza-Solé A, Formiga F, Comín-Colet J. Telemedicine strategies in older patients with cardiovascular diseases. J Transl Int Med. 2025;13:97-99. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in RCA: 1] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 68. | van Beugen S, Ferwerda M, Hoeve D, Rovers MM, Spillekom-van Koulil S, van Middendorp H, Evers AW. Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy for patients with chronic somatic conditions: a meta-analytic review. J Med Internet Res. 2014;16:e88. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 125] [Cited by in RCA: 129] [Article Influence: 10.8] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 69. | Bohlmeijer E, Prenger R, Taal E, Cuijpers P. The effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction therapy on mental health of adults with a chronic medical disease: a meta-analysis. J Psychosom Res. 2010;68:539-544. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 475] [Cited by in RCA: 388] [Article Influence: 24.3] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 70. | Petrovic M, Gaggioli A. Digital Mental Health Tools for Caregivers of Older Adults-A Scoping Review. Front Public Health. 2020;8:128. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 50] [Cited by in RCA: 39] [Article Influence: 6.5] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 71. | Rosland AM, Piette JD. Emerging models for mobilizing family support for chronic disease management: a structured review. Chronic Illn. 2010;6:7-21. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 111] [Cited by in RCA: 122] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 72. | Gilliss CL, Pan W, Davis LL. Family Involvement in Adult Chronic Disease Care: Reviewing the Systematic Reviews. J Fam Nurs. 2019;25:3-27. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 28] [Cited by in RCA: 53] [Article Influence: 7.6] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 73. | Welch V, Ghogomu ET, Barbeau VI, Dowling S, Doyle R, Beveridge E, Boulton E, Desai P, Huang J, Elmestekawy N, Hussain T, Wadhwani A, Boutin S, Haitas N, Kneale D, Salzwedel DM, Simard R, Hébert P, Mikton C. Digital interventions to reduce social isolation and loneliness in older adults: An evidence and gap map. Campbell Syst Rev. 2023;19:e1369. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Full Text (PDF)] [Cited by in Crossref: 7] [Cited by in RCA: 29] [Article Influence: 9.7] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 74. | Grey E, Baber F, Corbett E, Ellis D, Gillison F, Barnett J. The use of technology to address loneliness and social isolation among older adults: the role of social care providers. BMC Public Health. 2024;24:108. [RCA] [PubMed] [DOI] [Full Text] [Cited by in Crossref: 3] [Cited by in RCA: 12] [Article Influence: 6.0] [Reference Citation Analysis (0)] |

| 75. | Baez M, Ibarra F, Far IK, Ferron M, Casati F. Online Group-Exercises for Older Adults of Different Physical Abilities. 2016 International Conference on Collaboration Technologies and Systems (CTS); 2016 Oct 31-Nov 04; Orlando, FL, United States. IEEE, 2016: 524-533. |

Open Access: This article is an open-access article that was selected by an in-house editor and fully peer-reviewed by external reviewers. It is distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution NonCommercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: https://creativecommons.org/Licenses/by-nc/4.0/